Significance

Toll/interleukin-1 receptor/resistance protein (TIR) domains are present in plant and animal innate immunity receptors and appear to play a scaffold function in defense signaling. In both systems, self-association of TIR domains is crucial for their function. In plants, the TIR domain is associated with intracellular immunity receptors, known as nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptors (NLRs). Previous studies from several plant NLRs have identified two distinct interfaces that are required for TIR:TIR dimerization in different NLRs. We show that the two interfaces previously identified are both important for self-association and defense signaling of multiple TIR–NLR proteins. Collectively, this work suggests that there is a common mechanism of TIR domain self-association in signaling across the TIR–NLR class of receptor proteins.

Keywords: plant immunity, NLR, TIR domain, plant disease resistance, signaling by cooperative assembly formation

Abstract

The self-association of Toll/interleukin-1 receptor/resistance protein (TIR) domains has been implicated in signaling in plant and animal immunity receptors. Structure-based studies identified different TIR-domain dimerization interfaces required for signaling of the plant nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptors (NLRs) L6 from flax and disease resistance protein RPS4 from Arabidopsis. Here we show that the crystal structure of the TIR domain from the Arabidopsis NLR suppressor of npr1-1, constitutive 1 (SNC1) contains both an L6-like interface involving helices αD and αE (DE interface) and an RPS4-like interface involving helices αA and αE (AE interface). Mutations in either the AE- or DE-interface region disrupt cell-death signaling activity of SNC1, L6, and RPS4 TIR domains and full-length L6 and RPS4. Self-association of L6 and RPS4 TIR domains is affected by mutations in either region, whereas only AE-interface mutations affect SNC1 TIR-domain self-association. We further show two similar interfaces in the crystal structure of the TIR domain from the Arabidopsis NLR recognition of Peronospora parasitica 1 (RPP1). These data demonstrate that both the AE and DE self-association interfaces are simultaneously required for self-association and cell-death signaling in diverse plant NLRs.

Plants have evolved a sophisticated innate immune system to detect pathogens, in which plant resistance (R) proteins recognize pathogen proteins (effectors) in a highly specific manner. This recognition leads to the effector-triggered immunity (ETI) response that often induces a localized cell death known as the hypersensitive response (1). Most R proteins belong to the nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptor (NLR) family. NLRs are prevalent in the immune systems of plants and animals and provide resistance to a broad range of pathogens, including fungi, oomycetes, bacteria, viruses, and insects (2, 3). NLRs contain a central nucleotide-binding (NB) domain, often referred to as the nucleotide-binding adaptor shared by APAF-1, resistance proteins, and CED-4 (NB-ARC domain) (4) and a C-terminal leucine-rich repeat (LRR) domain. Plant NLRs can be further classified into two main subfamilies, depending on the presence of either a Toll/interleukin-1 receptor domain (TIR–NLR) or a coiled-coil domain (CC–NLR) at their N termini (5).

The CC and TIR domains of many plant NLRs can autonomously signal cell-death responses when expressed ectopically in planta, and mutations in these domains within full-length proteins also compromise signaling, suggesting that these domains are responsible for propagating the resistance signal after activation of the receptor (6–14). Self-association of both TIR (8, 9, 11, 15) and CC (10, 13, 16, 17) domains has been shown to be important for the signaling function. In animal NLRs, the formation of postactivation oligomeric complexes, such as the NLRC4/NAIP inflammasome or the APAF1 apoptosome, is important for bringing together N-terminal domains into a signaling platform (18–20), but there is yet little evidence for such signaling complexes in plants.

Several crystal structures of plant TIR domains have been reported (9, 11, 21–24). These structures reveal a similar overall structure, which consists of a flavodoxin-like fold containing a central parallel β-sheet surrounded by α-helices. This fold is shared with the TIR domains from animal innate immunity proteins, although plant TIR domains generally have an extended αD-helical region that is not found in the animal TIR domains. Whereas the overall structure of plant TIR domains is conserved, the identified self-association interfaces differ. The crystal structure of L6TIR revealed an interface predominantly formed by the αD- and αE-helices (termed here the DE interface) (9). Mutations in this interface disrupt L6TIR self-association and signaling activity (9). In the case of disease resistance protein RPS4 TIR domain (RPS4TIR) and disease resistance protein RRS1 TIR domain (RRS1TIR), an interface involving the αA- and αE-helices (the AE interface) was observed in the crystal structures of both individual protein domains and of the RPS4TIR:RRS1TIR heterodimer (11). Dimerization of RPS4TIR:RRS1TIR and self-association of RPS4TIR are dependent on the integrity of the AE interface, and mutations that disrupt this interface prevent both resistance signaling of the RPS4:RRS1 NLR pair and the autoactivity of RPS4TIR.

The different dimerization interfaces in L6TIR and RPS4TIR raise the question of whether either or both of these interfaces have conserved roles in other TIR–NLRs. To address this question, we investigated the structure and function of TIR domains from several plant NLRs. We present the crystal structures of TIR domains from the Arabidopsis NLR proteins suppressor of npr1-1, constitutive 1 (SNC1) (25) and recognition of Peronospora parasitica 1 (RPP1) (26). The two structures reveal the presence of both DE- and AE-type interaction interfaces. Site-directed mutagenesis of SNC1, L6, and RPS4 reveals that both the AE- and DE-interaction surface regions can be simultaneously involved in self-association (L6 and RPS4) and are required for signaling of these TIR domains. These data imply that self-association through both the AE and DE interfaces plays a general role in TIR-domain signaling in plant immunity.

Results

The Crystal Structure of SNC1TIR Reveals RPS4 and L6-Like Interfaces.

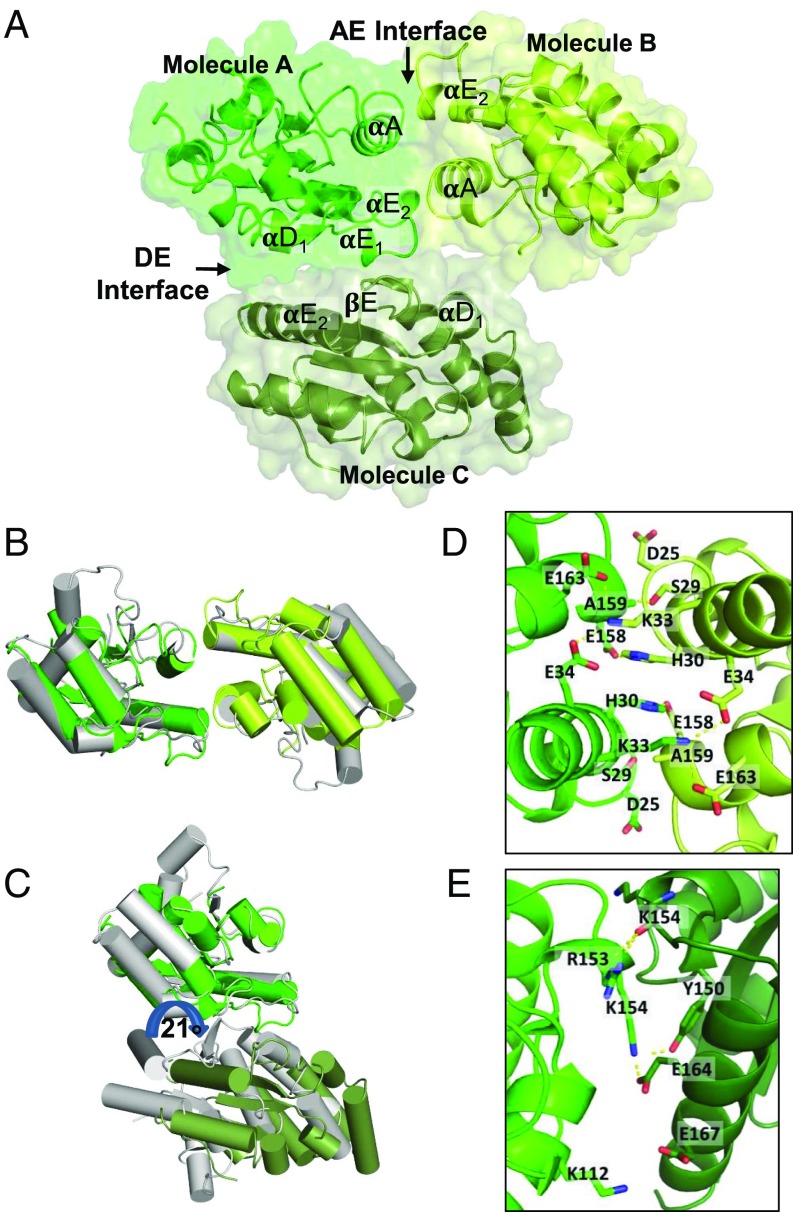

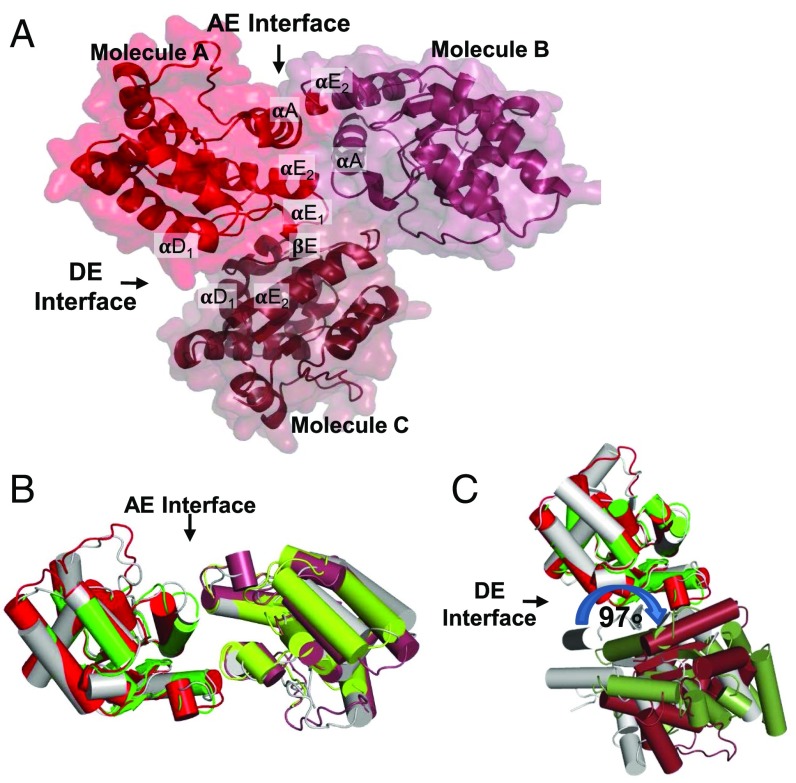

We crystallized the TIR domain (residues 8–181) from the Arabidopsis NLR protein SNC1 (SNC1TIR) (27) and determined the structure at 2.2-Å resolution (SI Appendix, Table S1). The fold features a four-stranded β-sheet (strands βA and βC–βE) surrounded by α-helices (αΑ–αE) (SI Appendix, Figs. S1 and S2A). No electron density was observed for the terminal residues (8–9 and 176–181) and residues 46–57 (corresponding to the βB-strand loop helix in L6TIR; SI Appendix, Figs. S1 and S2A).

In the SNC1TIR crystal, there are two prominent interfaces between molecules (Fig. 1A). These interfaces have striking similarities to the AE and DE interface that we previously observed in the structures of RPS4TIR and L6TIR, respectively (Fig. 1 B and C). Hyun et al. also observed the analogous interfaces in a recent report (24). The AE interface is formed by a symmetrical interaction involving the αA and αE helices (Fig. 1D) of the two molecules (hereafter designated molecules “A” and “B”), yielding a total buried surface area of ∼1,000 Å2. The AE interface in SNC1TIR contains the conserved SH (serine–histidine) motif (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 A and B), which is required for RPS4TIR autoactivity and RPS4TIR:RRS1TIR dimerization and function of the full-length paired-NLR proteins (11). Side chains of the two histidines (H30A and H30B, located in the center of opposing αA-helices) stack, with the neighboring serines (S29) forming hydrogen-bonding interactions with the backbone of A159 in the opposing αE-helices (Fig. 1D). The AE interface is further stabilized by a dense hydrogen-bonding network and electrostatic interactions between charged residues of the αA- and αE-helices that flank the SH motif, including interactions K33A–E34B and E164B, H30A–E158B, and E158A–D25B.

Fig. 1.

The crystal structure of SNC1TIR reveals two self-association interfaces. (A) SNC1TIR crystal structure contains two major interfaces, involving predominantly αA and αE (AE) and αD and αE (DE) regions of the protein. The green and lime-colored SNC1TIR molecules are observed in the asymmetric unit and interact through the AE interface; the green molecule also interacts with a crystallographic symmetry-related molecule (forest colored) through the DE interface. (B) Superposition of the SNC1TIR (green and lime) and RPS4TIR (gray) AE-interface dimers; one chain in the pair was used for superposition. (C) As in B, but showing the superposition of SNC1TIR and L6TIR (gray) DE-interface dimers; note the ∼21° rotation at the DE interface between the two structures. (D) Residues that contribute to the buried surface in the AE-interface interactions in SNC1TIR are highlighted in stick representation. (E) As in D, showing the DE interface.

The DE interface in SNC1TIR involves the αD1- and αE-helices and the connecting loops and strands (molecules “A” and “C”). There are fewer hydrogen-bonding interactions in it, compared with the AE interface; however, several complementary hydrophobic residues are buried (Fig. 1E and SI Appendix, Fig. S2B). Residues within the βE-strand and αE-helices of the contacting molecules form hydrogen bonds (K154C–G149A and Y150A; K154A–R153C). E164A and E167A form salt bridges with K154C and K112C, respectively. The DE interface also contains a cation–π interaction between the W155A aromatic ring and the R153C side chain (SI Appendix, Fig. S2B). The SNC1TIR and L6TIR DE interfaces involve similar surface regions (Fig. 1C), although after superimposition of one molecule in the pair, the second SNC1TIR and L6TIR molecules are rotated ∼21° relative to each other (Fig. 1C). Unlike L6TIR, the αD3-helix of SNC1TIR does not contribute to the interactions with the neighboring molecule in the crystal lattice, and the interface in SNC1TIR is slightly smaller than in L6TIR (buried surface area 812 Å2 for SNC1TIR and 890 Å2 for L6TIR). Sequence analysis of plant TIR domains reveals that most of the coordinating residues involved in the DE interface in SNC1TIR are not conserved (including K112, K154, and E164), with the exception of G149 (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 C and D), contrasting the conservation in the AE interface.

Self-Association of SNC1TIR in Solution Is Disrupted by Mutations in the AE Interface.

Reversible self-association in solution is observed for L6TIR and RPS4TIR (9, 11). We used size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) coupled to multiangle light scattering (MALS) to examine the ability of SNC1TIR to self-associate in solution. By SEC-MALS, the average molecular mass of SNC1TIR was higher than the theoretical molecular mass of a monomer (20.1 kDa) and increased with protein loading (Fig. 2A). Using the complementary technique small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS), a similar concentration-dependent increase in average molecular mass was observed (Fig. 2B). These data suggest that SNC1TIR self-associates in solution in a concentration-dependent manner and is in a rapid equilibrium between monomeric and oligomeric (dimeric or higher-order) protein species.

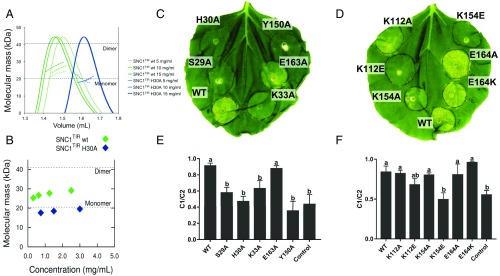

Fig. 2.

SNC1TIR self-association and signaling. (A) Solution properties of SNC1TIR (WT, wild-type) and SNC1TIR H30A analyzed by SEC-MALS. Green or blue peaks indicate the traces from the refractive index (RI) detector during SEC of SNC1TIR or its H30A mutant, respectively. The lines under the peaks correspond to the average molecular mass distributions across the peak (using equivalent coloring). (B) Molecular masses calculated from SAXS data for SNC1TIR (WT, wild-type; green diamonds) and SNC1TIR H30A (blue diamonds), calculated from static samples at discrete concentrations between 3 and 0.25 mg/mL. Dotted lines indicate the theoretical monomeric and dimeric masses. (C–F) In planta mutational analysis of SNC1TIR. (C and D) Autoactive phenotype of SNC1TIR (residues 1–226; WT, wild-type) and the corresponding mutants upon Agrobacterium-mediated transient expression in N. benthamiana leaves. Each construct was coexpressed with the virus-encoded suppressor of gene silencing P19 (33). Photos were taken 5 d after infiltration. (E and F) Ion-leakage measurement of the infiltrated leaves as shown in C and D. Each construct was expressed in independent leaves. Leaf disk samples were collected 2 d after infiltration and incubated in Milli-Q water. C1 corresponds to the ions released in solution 24 h after sampling. C2 corresponds to the total ion contents in the sample (see SI Appendix, Methods for details). Ion leakage was calculated as C1/C2 ratio. N. benthamiana leaves expressing P19 only were used as control. Error bars show SE of means. Statistical differences, calculated by one-way ANOVA and multiple comparison with the control, are indicated by letters.

L6TIR and RPS4TIR self-association in solution was shown to be dependent on the DE and AE interfaces, respectively (9, 11). To test whether these protein surfaces play a role in SNC1TIR self-association, key residues involved in forming the two interfaces were mutated (to alanine or amino acid of opposite charge) and the mutant proteins tested using SEC-MALS. These residues include four in the AE interface (S29, H30, K33, and E163), and four in the DE interface (K112, Y150, K154, and E164). Recombinant proteins of all mutants, except Y150A, were successfully produced in Escherichia coli. With the exception of E163A, all mutants in the AE interface had average molecular masses close to the expected monomeric mass of SNC1TIR (SI Appendix, Table S2 and Fig. S4A), and there was no concentration-dependent increase in the molecular mass of the H30A mutant when analyzed by SEC-MALS and SAXS (Fig. 2 A and B). Therefore, the S29A, H30A, and K33A mutations disrupt SNC1TIR self-association in solution. The E163A mutant had a reduced molecular mass compared with the wild-type protein, suggesting this mutation had a weaker effect on SNC1TIR self-association, probably due to its location at the periphery of the AE interface. By contrast, we could not detect an effect on self-association of mutants in the DE interface (K112A or E, K154A or E, and E164A or K) using SEC-MALS. These observations suggest that the AE interface contributes more than the DE interface to the self-association of the SNC1TIR in solution.

SNC1TIR Autoactivity Is Disrupted by Mutations in Either AE or DE Interfaces.

To test the biological relevance of the AE and DE interfaces for SNC1TIR function, we tested the effect of interface mutations on SNC1TIR cell-death signaling. Agrobacterium-mediated transient expression of SNC1TIR (residues 1–226) in Nicotiana benthamiana induced a visible chlorotic cell-death phenotype 5 d after infiltration. Expression of mutants in the AE interface, including S29A, H30A, and K33A, resulted in a much weaker cell-death response and a significantly reduced level of ion leakage compared with the wild-type protein (SI Appendix, Table S2 and Fig. 2 C–F). The E163A mutant, which showed modestly impaired self-association in solution, did not reduce the level of cell-death phenotype nor ion leakage, compared with the wild-type protein. Overall, these effects correlate well with the effects on self-association, suggesting that the integrity of the AE interface is required for both TIR domain self-association and signaling activity.

Amino acid substitutions of the DE-interface residues also affected SNC1TIR autoactivity (SI Appendix, Table S2 and Fig. 2 C–F). The Y150A mutation, which is at the center of the SNC1TIR DE interface, significantly disrupted autoactivity. Notably, L6TIR has a tryptophan residue (W202) at the equivalent position (SI Appendix, Fig. S1) and its substitution with alanine abolished L6TIR self-association in yeast and signaling activity in planta (9). Both K112E and K154E mutations in SNC1TIR led to a reduced cell-death phenotype level, whereas alanine substitution of either residue did not, consistent with electrostatic interactions through the charged side chains. By contrast, neither A nor K substitutions of the E164 residue affected cell-death development. All mutants were detected by immunoblotting and had similar protein expression levels (SI Appendix, Fig. S5A), indicating the abolition of autoactivity was not due to protein-expression differences.

Residues in the AE Interface Contribute to L6TIR Self-Association and Autoactivity.

We previously showed that the DE interface was involved in L6TIR self-association and autoactivity (9), but the AE interface was not observed in the L6TIR crystal structure. To test whether the AE interface is relevant for L6TIR function, we first modeled this potential interface by superimposing the L6TIR molecules onto the RPS4TIR AE-interface dimer (SI Appendix, Fig. S6A). The L6TIR has a phenylalanine (F79) at the position equivalent to the conserved histidine that forms the core of the AE interfaces in both RPS4TIR and SNC1TIR (Fig. 1D and SI Appendix, Fig. S6A). The equivalent residue is a phenylalanine in AtTIR, where it is involved in an AE interface in a stacking arrangement analogous to the histidine residues in SNC1TIR and RPS4TIR (11, 22). An aspartate residue precedes F79 in L6TIR, occupying the position of the conserved serine in RPS4TIR. The modeling also indicates that residues E74 and Q82 in the αA-helix, and K209 in the αE-helix could form hydrogen bonds in a potential AE-interface interaction in L6TIR.

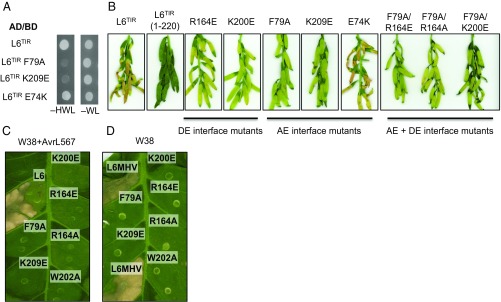

To test whether the AE interface is involved in L6TIR function, we examined the effect of amino acid substitutions in this interface on its self-association. Mutations of residues F79A and K209E disrupted L6TIR self-association in yeast-two-hybrid (Y2H) assays, whereas the E74K mutation did not (Fig. 3A). Protein expression of the BD fusion of the F79A mutant was detected at very low levels (SI Appendix, Fig. S5B), which may prevent this mutant from triggering yeast growth. However, the K209E and E74K mutant constructs were stably expressed in yeast (SI Appendix, Fig. S5B).

Fig. 3.

Mutations in both AE and DE interfaces affect L6TIR self-association and autoactivity and full-length L6 effector-dependent and effector-independent cell-death signaling. (A) Mutations in the AE interface disrupt L6TIR self-association in yeast. Growth of yeast cells expressing GAL4-BD and GAL4-AD fusions of L6TIR (residues 29–233) or L6TIR mutants on nonselective media lacking tryptophan and leucine (−WL) or selective media additionally lacking histidine (−HWL). (B) Mutations in the AE interface disrupt L6TIR signaling activity in planta. Cell-death signaling activity of L6TIR (residues 1–233) mutants fused to yellow fluorescent protein (YFP), 12 d after agroinfiltration in flax plants. The truncated L6 TIR domain (residues 1–220) was used as a negative control (9). Agrobacterium cultures carrying L6TIR mutants were adjusted to OD1. (C–D) Representative cell-death activity of L6 (C) and L6MHV (D) mutants, fused to YFP, 3 d after agroinfiltration in wild-type tobacco W38 or transgenic tobacco W38 carrying AvrL567, respectively. Agrobacterium cultures carrying L6 and L6MHV mutant were adjusted to OD 0.5.

SEC-MALS and SEC-SAXS analysis of purified recombinant L6TIR (residues 29–233) revealed an average molecular mass of 38.5 kDa, which is between the expected mass for a monomer (23.4 kDa) and dimer (46.8 kDa) (SI Appendix, Table S2 and Fig. S4 B and C), consistent with previous analysis (9). Substitutions of residues F79 or K209 by alanine or negatively charged residues resulted in a decreased (although slightly larger than monomer) average molecular mass (SI Appendix, Table S2 and Fig. S4B), consistent with the absence of interaction observed in yeast. The E74K mutant could not be produced recombinantly in E. coli. Likewise, mutations in the L6TIR DE interface previously shown to affect L6TIR self-association (9) also led to a decreased (although slightly larger than monomer) average molecular mass in solution (SI Appendix, Table S2 and Fig. S4B). L6TIR with substitutions in both interfaces, including F79A/R164A and F79A/K200E, had an average molecular mass consistent with monomer (SI Appendix, Table S2 and Fig. S4B), suggesting that self-association in solution was fully abolished in these double interface mutants. Strikingly, the R164E mutation led to a molecular mass close to a trimer (70.2 kDa) and the F79A/R164E double mutant had an average molecular mass between those expected for dimer and trimer (SI Appendix, Table S2 and Fig. S4C). These observations suggest that the AE and DE interfaces both contribute to L6TIR self-association in solution and in yeast.

We then tested the effect of the AE- and DE-interface mutations on L6TIR autoactivity, using Agrobacterium-mediated transient expression in flax. As previously reported (9), mutations in the DE interface such as R164A/E and K200E significantly reduced the L6TIR autoactive phenotype. The F79A and K209E mutations in the AE interface, which affected self-association, also suppressed L6TIR autoactivity, whereas the E74K mutation (which had no effect on self-association in Y2H) did not (Fig. 3B). Double mutations in both interfaces, including F79A/R164A, F79A/R164E, and F79A/K200E, resulted in similar phenotypes to the single mutations. All mutants were stably expressed in flax leaves (SI Appendix, Fig. S5C). These observations suggest that both the AE and DE interfaces contribute to autoactivity of L6TIR; however, neither single nor double mutations completely abolish L6TIR signaling activity.

Both AE and DE Interfaces Are Required for L6 Effector-Dependent and Effector-Independent Signaling Activation.

We generated AE- and DE-interface mutants in the full-length L6 protein and tested their effects on effector-dependent and effector-independent cell-death signaling. Agrobacterium-mediated transient expression of L6 in transgenic Nicotiana tabacum (tobacco) leaves, expressing the corresponding flax-rust (Melampsora lini) effector protein AvrL567, induces a strong cell-death response (9) (Fig. 3C). Mutations in both the AE (F79A and K209E) and the DE (K200E, R164E, R164A, and W202A) interfaces abolished L6 effector-dependent cell-death signaling (Fig. 3C). Immunoblot analysis showed that the K209E construct was not expressed in tobacco, whereas all of the other constructs expressed at a comparable level to the wild-type L6 protein (SI Appendix, Fig. S5D).

These mutations were also introduced in the autoactive variant of L6, L6MHV, which contains a D-to-V mutation in the MHD motif in the ARC2 subdomain and induces a strong necrotic reaction when transiently expressed in wild-type tobacco W38 without AvrL567 (28). Mutations in both the AE and DE interfaces abolished this autoactive cell-death reaction (Fig. 3D), although small cell-death spots were observed with L6MHV R164A mutant. Immunoblotting showed that all mutant proteins were expressed in planta (SI Appendix, Fig. S5E). Thus, mutations in either AE or DE interfaces suppress L6 effector-dependent and effector-independent cell-death signaling.

Residues in the DE Interface Contribute to RPS4TIR Self-Association and Autoactivity.

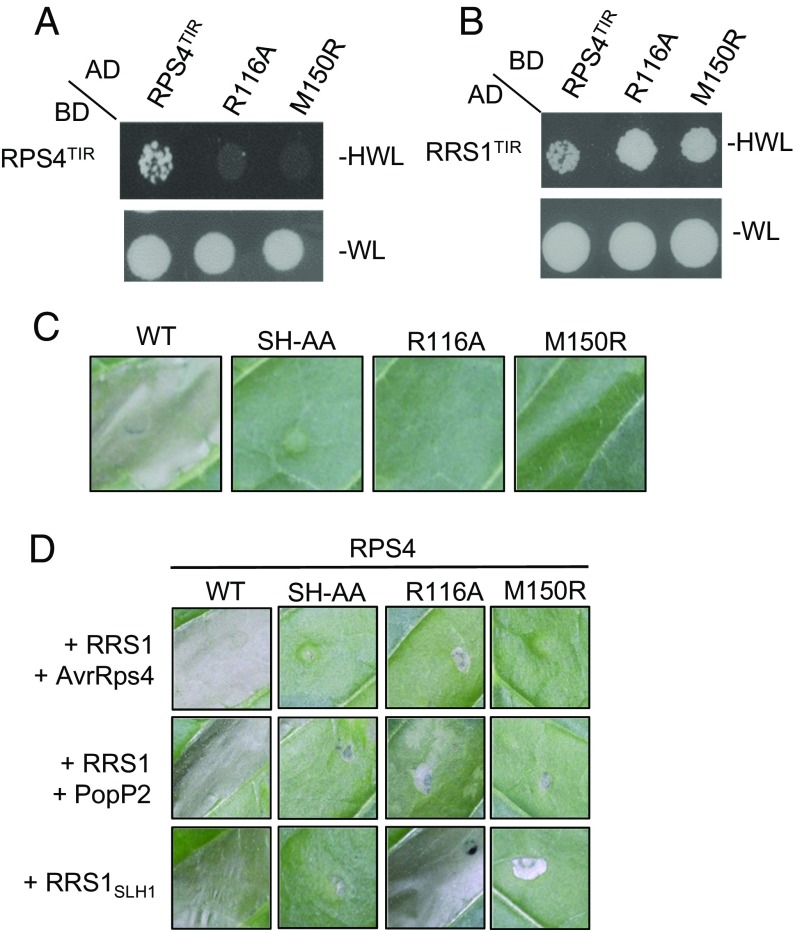

When overexpressed in planta, RPS4TIR is autoactive and triggers an effector-independent cell-death response (7). RPS4TIR self-associates and can form a heterodimer with RRS1TIR through the AE interface (11). The DE interface is not observed in the crystal structures of RPS4TIR, RRS1TIR, or their heterodimer. To test whether the DE interface could also play a role in RPS4TIR self-association, heterodimerization with RRS1, and autoactivity, we first generated a model of the DE interface in RPS4TIR, by superposition of RPS4TIR onto the L6TIR DE-interface dimer (SI Appendix, Fig. S6B). The L6 residues R164 and K200 appear to play important roles in stabilizing the DE-interface structure and mutation of either residue suppresses L6TIR self-association and autoactivity (9). Mutation of the equivalent residues in RPS4TIR (R116 or M150), abolished RPS4TIR self-association in Y2H assays (Fig. 4A), but did not affect its interaction with RRS1TIR or protein accumulation in yeast (Fig. 4B and SI Appendix, Fig. S5F). The self-association of these RPS4TIR mutants was further examined using SEC-MALS. RPS4TIR (residues 10–178, equivalent to the crystal structure) had an average molecular mass of 21.1 kDa, which is only slightly higher than the expected monomeric mass of 19.6 kDa (SI Appendix, Table S2 and Fig. S4D). We previously reported a similar in-solution molecular mass of ∼23 kDa for RPS4TIR in a slightly different experimental setup (11). The AE-interface mutant S33A, which was previously shown to reduce the RPS4TIR self-association (11), led to an average molecular mass of 19.9 kDa (SI Appendix, Table S2). The R116A in the DE interface also resulted in a slight average molecular mass reduction, whereas the M150R mutation was indistinguishable from the wild-type protein (SI Appendix, Table S2 and Fig. S4D). Although consistent with the DE-interface R116A mutation suppressing RPS4TIR self-association in solution, the low level of self-association of wild-type RPS4TIR detected in this assay and the minor differences observed for the mutants indicate that SEC-MALS may not be sufficiently sensitive to confirm this interaction. Nevertheless, the Y2H data suggest that mutations in both the DE and AE interfaces disrupt RPS4TIR self-association.

Fig. 4.

Mutations in both AE and DE interfaces affect RPS4TIR self-association and autoactivity and full-length RPS4 effector-dependent and effector-independent cell-death signaling. (A) Mutations in the DE interface disrupt RPS4TIR self-association in yeast. Growth of yeast cells expressing GAL4-BD fusion and GAL4-AD fusion of RPS4TIR (residues 1–183) or RPS4TIR mutants on nonselective media lacking tryptophan and leucine (−WL) or selective media additionally lacking histidine (−HWL). (B) Mutations in the DE interface do not affect RPS4TIR interaction with RRS1TIR. Growth of yeast cells coexpressing GAL4-BD fusion of RPS4TIR or RPS4TIR mutants and GAL4-AD fusion of RRS1TIR (residues 1–185) on −WL or −HWL media. (C) Mutations in the DE interface disrupt RPS4TIR signaling activity in planta. Cell-death signaling activity of RPS4TIR (WT, wild-type) and its mutants fused to C-terminal 6xHA tags, 3 d after agroinfiltration in tobacco. (D) Representative cell-death activity of full-length RPS4 (WT, wild-type) and its mutants fused to C-terminal 3xHA tags, upon agro-mediated transient coexpression with RRS1 and corresponding effectors (AvrRps4 or PopP2), or with RRS1SLH1 mutant in W38 tobacco. Agrobacterium cultures were adjusted to OD 0.1. Photos were taken 5 d after agroinfiltration.

We then tested the effect of the DE-interface mutations on RPS4TIR autoactivity. When transiently expressed in tobacco W38, RPS4TIR (residues 1–236) triggered a cell-death response, whereas mutations of the SH motif (SH-AA) in the AE interface as well as either of the R116 and M150 residues in the DE interface abolished this autoactive phenotype (Fig. 4C). All mutants were expressed at similar levels to the wild-type RPS4TIR (SI Appendix, Fig. S5G). These observations suggest that the integrity of both AE and DE interfaces is required for the self-association and autoactivity of RPS4TIR, but the AE interface is the primary interface for RPS4TIR and RRS1TIR heterodimerization.

Both AE and DE Interfaces Are Required for RRS1:RPS4 Effector-Dependent and Effector-Independent Activation.

We further examined whether the mutations in the putative DE interface affect effector-dependent activation of the full-length RRS1:RPS4 protein pair. We previously reported that coexpression of RPS4 and RRS1 with the effectors AvrRps4 or PopP2 in tobacco triggers a strong cell-death response that is abolished by mutations of the SH motif in the AE interface (11). Similarly, mutants in the DE interface also affected RRS1:RPS4 effector-triggered cell death, although the proteins were all expressed (Fig. 4D and SI Appendix, Fig. S5H). The M150R mutant triggered no cell-death response when coexpressed with RRS1 and either effector. Mutation of R116 also disrupted AvrRps4 recognition but induced a weak cell-death response upon PopP2 recognition. To measure the effect of mutations in the DE interface on RPS4 effector-independent signaling, we coexpressed RPS4 mutants with the RRS1SLH1 variant, which contains a single amino acid (leucine) insertion in the WRKY domain and activates effector-independent cell death in the presence of RPS4 (11, 29). Mutations of the SH motif in RPS4 abolished cell-death signaling (Fig. 4D). The M150R mutant also disrupted RPS4 effector-independent cell death, whereas the R116A mutation did not (Fig. 4D). The greater effect of the M150R mutation compared with R116A on full-length RPS4 protein function may be due to its central position in the DE interface, whereas R116 is located at the periphery of the RPS4TIR DE interface. These observations further corroborate that, whereas both interfaces are involved in RPS4TIR self-association and signaling, the AE interface is the primary interface for RPS4TIR and RRS1TIR heterodimerization.

The Crystal Structure of the RPP1TIR Features AE and DE Interfaces.

We recently showed that alleles of the Arabidopsis NLR protein RPP1 from ecotypes Niederzenz (NdA) and Wassilewskija (WsB) differ in their ability to induce effector-independent cell death via transient expression of the TIR domain in planta (15). RPP1 NdA-1 and WsB alleles differ by 17 substitutions in the TIR domain. Biophysical and functional analyses of proteins where these residues are mutated show a correlation between self-association and the ability for RPP1 TIR domains to induce effector-independent cell death (15). In light of these findings, we undertook structural studies of the RPP1 NdA-1 TIR domain (residues 93–254; RPP1TIR). Strikingly, the crystal structure (2.8-Å resolution; SI Appendix, Table S1) reveals AE and DE interfaces analogous to SNC1TIR (Fig. 5 A–C and SI Appendix, Fig. S7). Upon superposition of one molecule in the DE-interface dimers, the αE-helix is rotated ∼97° in RPP1TIR compared with its position in L6TIR in the other molecule (Fig. 5C). Despite this difference to other TIR domain structures, there are common residues within the AE and DE interfaces of the RPP1 crystal structure (SI Appendix, Fig. S7).

Fig. 5.

The AE and DE interface in the crystal structure of RPP1TIR. (A) Ribbon representation of the RPP1 crystal structure and the AE and DE interfaces, with molecules sharing the AE interface colored red and raspberry and the DE interface, red and ruby. (B) Comparison of the AE interface from the RPS4TIR (gray), SNC1TIR (green and lime), and RPP1TIR (red and raspberry) with the chains on the Left superimposed, highlighting the strong structural conservation of the interface. (C) Comparison of the DE interface from the L6TIR (gray), SNC1TIR (green and forest), and RPP1TIR (red and ruby) structures; only the chains at the Top are superimposed, highlighting the rotation observed at the DE interface in these crystal structures.

Discussion

Structural Conservation of TIR Domain Interfaces in Plants.

TIR domains feature in innate immunity pathways across phyla (21); however, the molecular mechanisms of signaling by these domains have largely remained elusive. Whereas in mammalian TIR domains no common trends have emerged among the available crystals structures in terms of protein–protein association (21), most plant TIR-domain crystal structures feature structurally analogous AE interfaces (Figs. 1B and 5B) (23). The exception is L6TIR, the crystal structure of which features the DE but not the AE interface. DE interfaces are also observed in the two structures reported here, of SNC1TIR and RPP1TIR, and in the structure of AtTIR (SI Appendix, Fig. S8), albeit with some deviations in orientation (Figs. 1C and 5C and SI Appendix, Fig. S9). Whereas the presence or absence of an interface in the crystal does not prove or disprove a biological function (30), these observations precipitated a thorough assessment of interfaces in several proteins, as described here. We conclude that self-association through both the AE and DE interfaces plays a general role in TIR–NLR signaling.

TIR-Domain Self-Association and Signaling Through Conserved TIR Domain Interfaces.

We have previously shown that both L6TIR and RPS4TIR signaling requires self-association, focusing on the single dimerization interfaces (DE and AE, respectively) observed in these crystal structures. Here we show that mutations in either of the AE or DE interfaces suppress self-association, effector-dependent immunity, and effector-independent autoactivity in both L6TIR and RPS4TIR. In Y2H assays, single mutations to residues in distinct (either the AE or DE) interfaces abolish self-association, suggesting that in this assay, interaction through both interfaces is required for detection. Similarly, mutations of residues in either the AE or DE interfaces can independently abolish cell death. Collectively, these data suggest that self-association through AE and DE interfaces is required simultaneously to allow cell-death signaling by L6 and RPS4.

For SNC1TIR, both AE and DE interfaces are observed within the crystal structure. Although only mutations in the AE interface were observed to significantly affect SNC1TIR self-association in solution, mutations in either interface suppressed SNC1TIR cell-death signaling, indicating that the intergrity of both interfaces is required for function. In the case of RPP1TIR, several previously identified mutations that affect self-association and cell-death signaling (15) map to either the AE or DE interfaces in the RPP1TIR structure. Therefore, the data presented here and previously (9, 11, 15) suggest a correlation between TIR-domain self-association and cell-death signaling. One exception to this correlation is RPV1TIR from Mirabilis rotundifolia; no self-association of this protein could be detected in solution or yeast, but nevertheless, mutations within the predicted AE- and DE-interface regions suppressed its cell-death signaling function (23). All of the TIR:TIR domain interactions studied to date are weak and transient, with the exception of the heterodimer association between RRS1TIR and RPS4TIR, which appears to play an inhibitory rather than signaling role. Thus, the failure to detect RPV1TIR self-interaction may be due to the weak self-association of this TIR domain, below the detection threshold limit. The weak and transient nature of TIR:TIR domain interactions may be a key regulatory mechanism to reduce the occurrence of cell-death signaling in the absence of an appropriate stimulus. It is also likely that the TIR-domain self-association is stabilized by other domains in the NLR, by other proteins that promote cell-death signaling in planta, or that the TIR domains interact with nonself TIR domains in planta to propagate signaling. Regardless of the exact mechanisms, the required integrity of the AE and DE interfaces suggests that TIR:TIR domain association through both these interfaces is a general requirement for function.

Cooperative Assembly of TIR Domains.

Higher-order assembly formation has become an emerging theme in diverse innate immunity pathways. Protein domains from the death-domain family appear to be able to form large, often open-ended helical structures (31). Signaling by cooperative assembly formation (SCAF) explains the ultrasensitive all-or-none response desirable in such pathways (2). One notable feature of the AE and DE interface is that they are not mutually exclusive. In fact, based on the SNC1TIR domain structure, it is possible to build a hypothetical extended TIR domain superhelix propagated through the AE and DE interfaces that are observed in the crystal structure (SI Appendix, Fig. S10A). An AE interface is also conserved and functional in L6TIR; therefore, it is possible for L6TIR to oligomerize through the conserved AE interface and the DE interface observed in the L6TIR crystals. Such an assembly results in a superhelix similar to the one proposed for SNC1TIR (SI Appendix, Fig. S10B). The same is not possible for RPP1TIR, as rotation around the DE interface causes a clash when constructing the hypothetical superhelix (SI Appendix, Fig. S10C). As such, the varying rotations of different TIR domains suggest there is flexibility in this region, and that a specific geometry is required for TIR domains to form larger oligomeric structures. To date, the only evidence of a TIR-domain self-association complex greater than a dimer was observed in the L6TIR carrying an R164E mutation. The R164E actually suppresses signaling, but the mutant self-associates more strongly in solution compared with wild-type L6TIR. Interstingly, the R164A mutation reduces both signaling and self-association, suggesting that the charge substitution mutation at this site may favor an altered specific geometry of association, leading to the formation of an inactive oligomer.

Signaling by Plant TIR Domains in a TIR–NLR Receptor.

Ultimately, we need to consider the AE- and DE-interface interactions in the context of a full-length TIR–NLR receptor. Although to date there is no structural data for a full-length receptor, analysis of their mammalian NLR counterparts demonstrates that the nucleotide-binding domain plays a key role in the self-association of the NLRC4 receptor into 10–12 subunit oligomers (18, 19). If plant NLRs follow a nucleated NB-mediated assembly mechanism as observed in animal NLRs (2, 18, 19), this could elegantly induce a proximity-induced assembly of the associated TIR domains through the AE and DE interfaces. Data are starting to emerge on NLR oligomerization upon effector recognition (specifically in tobacco N protein (32) and Arabidopsis RPP1 (15)). Many plant TIR domains do not show autoactivity outside the context of the full-length protein (7, 15), suggesting they may not be able to interact adequately on their own without the help from other domains in the NLR.

Materials and Methods

Details of the methods used are provided in SI Appendix, Methods, including cloning details for vectors and gene constructs, crystallization and structure determination using X-ray crystallography, biophysical experiments including SEC-MALS and SAXS experiments, transient expression in planta, Y2H assays, immunoblot analysis, and ion-leakage measurements.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Stella Césari for discussion and assistance with the in planta immunoprecipitation experiments, Kim Newell for excellent technical support, and Daniel Ericsson for help with X-ray data processing. We acknowledge the use of the University of Queensland Remote Operation Crystallization and X-Ray Diffraction Facility. This research used macromolecular crystallography (MX) and small/wide angle X-ray scattering (SAXS/WAXS) beamlines at the Australian Synchrotron, Victoria, Australia. This research was supported by the Australian Research Council (ARC) Discovery Projects (DP120100685, DP120103558, and DP160102244) and the National Science Foundation (NSF-IOS-1146793 to B.J.S.). B.K. is a National Health and Medical Research Council Research Fellow (1003325 and 1110971). M.B. and S.J.W. are recipients of ARC Discovery Early Career Research Awards (DE130101292 and DE160100893, respectively).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data deposition: The protein structures and data used to derive these structures have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org [PDB ID codes 5TEB (RPP1TIR) and 5TEC (SNC1TIR)].

See Commentary on page 2445.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1621248114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Dodds PN, Rathjen JP. Plant immunity: Towards an integrated view of plant-pathogen interactions. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11(8):539–548. doi: 10.1038/nrg2812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bentham A, Burdett H, Anderson PA, Williams SJ, Kobe B. Animal NLRs provide structural insights into plant NLR function. Ann Bot. August 24, 2016 doi: 10.1093/aob/mcw171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duxbury Z, et al. Pathogen perception by NLRs in plants and animals: Parallel worlds. BioEssays. 2016;38(8):769–781. doi: 10.1002/bies.201600046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van der Biezen EA, Jones JD. The NB-ARC domain: A novel signalling motif shared by plant resistance gene products and regulators of cell death in animals. Curr Biol. 1998;8(7):R226–R227. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70145-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McHale L, Tan X, Koehl P, Michelmore RW. Plant NBS-LRR proteins: Adaptable guards. Genome Biol. 2006;7(4):212. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-4-212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frost D, et al. Tobacco transgenic for the flax rust resistance gene L expresses allele-specific activation of defense responses. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2004;17(2):224–232. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2004.17.2.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swiderski MR, Birker D, Jones JD. The TIR domain of TIR-NB-LRR resistance proteins is a signaling domain involved in cell death induction. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2009;22(2):157–165. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-22-2-0157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krasileva KV, Dahlbeck D, Staskawicz BJ. Activation of an Arabidopsis resistance protein is specified by the in planta association of its leucine-rich repeat domain with the cognate oomycete effector. Plant Cell. 2010;22(7):2444–2458. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.075358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bernoux M, et al. Structural and functional analysis of a plant resistance protein TIR domain reveals interfaces for self-association, signaling, and autoregulation. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;9(3):200–211. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maekawa T, et al. Coiled-coil domain-dependent homodimerization of intracellular barley immune receptors defines a minimal functional module for triggering cell death. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;9(3):187–199. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams SJ, et al. Structural basis for assembly and function of a heterodimeric plant immune receptor. Science. 2014;344(6181):299–303. doi: 10.1126/science.1247357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang GF, et al. Molecular and functional analyses of a maize autoactive NB-LRR protein identify precise structural requirements for activity. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11(2):e1004674. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cesari S, et al. Cytosolic activation of cell death and stem rust resistance by cereal MLA-family CC-NLR proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113(36):10204–10209. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1605483113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kanzaki H, et al. Arms race co-evolution of Magnaporthe oryzae AVR-Pik and rice Pik genes driven by their physical interactions. Plant J. 2012;72(6):894–907. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.05110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schreiber KJ, Bentham A, Williams SJ, Kobe B, Staskawicz BJ. Multiple domain associations within the Arabidopsis immune receptor RPP1 regulate the activation of programmed cell death. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12(7):e1005769. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Casey LW, et al. The CC domain structure from the wheat stem rust resistance protein Sr33 challenges paradigms for dimerization in plant NLR proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113(45):12856–12861. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1609922113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Collier SM, Hamel LP, Moffett P. Cell death mediated by the N-terminal domains of a unique and highly conserved class of NB-LRR protein. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2011;24(8):918–931. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-03-11-0050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu Z, et al. Structural and biochemical basis for induced self-propagation of NLRC4. Science. 2015;350(6259):399–404. doi: 10.1126/science.aac5489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang L, et al. Cryo-EM structure of the activated NAIP2-NLRC4 inflammasome reveals nucleated polymerization. Science. 2015;350(6259):404–409. doi: 10.1126/science.aac5789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reubold TF, Wohlgemuth S, Eschenburg S. Crystal structure of full-length Apaf-1: How the death signal is relayed in the mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis. Structure. 2011;19(8):1074–1083. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ve T, Williams SJ, Kobe B. Structure and function of Toll/interleukin-1 receptor/resistance protein (TIR) domains. Apoptosis. 2015;20(2):250–261. doi: 10.1007/s10495-014-1064-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chan SL, Mukasa T, Santelli E, Low LY, Pascual J. The crystal structure of a TIR domain from Arabidopsis thaliana reveals a conserved helical region unique to plants. Protein Sci. 2010;19(1):155–161. doi: 10.1002/pro.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Williams SJ, et al. Structure and function of the TIR domain from the grape NLR protein RPV1. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1850. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hyun KG, Lee Y, Yoon J, Yi H, Song JJ. Crystal structure of Arabidopsis thaliana SNC1 TIR domain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;481(1–2):146–152. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang Y, Goritschnig S, Dong X, Li X. A gain-of-function mutation in a plant disease resistance gene leads to constitutive activation of downstream signal transduction pathways in suppressor of npr1-1, constitutive 1. Plant Cell. 2003;15(11):2636–2646. doi: 10.1105/tpc.015842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Botella MA, et al. Three genes of the Arabidopsis RPP1 complex resistance locus recognize distinct Peronospora parasitica avirulence determinants. Plant Cell. 1998;10(11):1847–1860. doi: 10.1105/tpc.10.11.1847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wan L, et al. Crystallization and preliminary X-ray diffraction analyses of the TIR domains of three TIR-NB-LRR proteins that are involved in disease resistance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Acta Crystallogr Sect F Struct Biol Cryst Commun. 2013;69(Pt 11):1275–1280. doi: 10.1107/S1744309113026614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bernoux M, et al. Comparative analysis of the flax immune receptors L6 and L7 suggests an equilibrium-based switch activation model. Plant Cell. 2016;28(1):146–159. doi: 10.1105/tpc.15.00303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Noutoshi Y, et al. A single amino acid insertion in the WRKY domain of the Arabidopsis TIR-NBS-LRR-WRKY-type disease resistance protein SLH1 (sensitive to low humidity 1) causes activation of defense responses and hypersensitive cell death. Plant J. 2005;43(6):873–888. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kobe B, et al. Crystallography and protein-protein interactions: Biological interfaces and crystal contacts. Biochem Soc Trans. 2008;36(Pt 6):1438–1441. doi: 10.1042/BST0361438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu H. Higher-order assemblies in a new paradigm of signal transduction. Cell. 2013;153(2):287–292. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mestre P, Baulcombe DC. Elicitor-mediated oligomerization of the tobacco N disease resistance protein. Plant Cell. 2006;18(2):491–501. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.037234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sainsbury F, Thuenemann EC, Lomonossoff GP. pEAQ: Versatile expression vectors for easy and quick transient expression of heterologous proteins in plants. Plant Biotechnol J. 2009;7(7):682–693. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2009.00434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.