Abstract

Background/Aims

The resistance rate of Helicobacter pylori is gradually increasing. We aimed to evaluate the efficacy of levofloxacin-based third-line H. pylori eradication in peptic ulcer disease.

Methods

Between 2002 and 2014, 110 patients in 14 medical centers received levofloxacin-based third-line H. pylori eradication therapy for peptic ulcer disease. Of these, 88 were included in the study; 21 were excluded because of lack of follow-up and one was excluded for poor compliance. Their eradication rates, treatment regimens and durations, and types of peptic ulcers were analyzed.

Results

The overall eradiation rate was 71.6%. The adherence rate was 80.0%. All except one received a proton-pump inhibitor, amoxicillin, and levofloxacin. One received a proton-pump inhibitor, amoxicillin, levofloxacin, and clarithromycin, and the eradication was successful. Thirty-one were administered the therapy for 7 days, 25 for 10 days, and 32 for 14 days. No significant differences were observed in the eradication rates between the three groups (7-days, 80.6% vs 10-days, 64.0% vs 14-days, 68.8%, p=0.353). Additionally, no differences were found in the eradiation rates according to the type of peptic ulcer (gastric ulcer, 73.2% vs duodenal/gastroduodenal ulcer, 68.8%, p=0.655).

Conclusions

Levofloxacin-based third-line H. pylori eradication showed efficacy similar to that of previously reported first/second-line therapies.

Keywords: Levofloxacin, Helicobacter pylori, Third-line eradication

INTRODUCTION

Helicobacter pylori is one of the main causes of peptic ulcer disease1,2 and its eradication is known to reduce recurrence rate of peptic ulcer dramatically.3 So far there have been many efforts to develop better antibiotic regimens to eradicate H. pylori since its first discovery by Marshall and Warren4 in 1980s. However, still no ideal treatment has been found. The eradication rate of the standard triple therapy is gradually decreasing and now we should be prepared to face patients with multiple eradication failures. In Korea where H. pylori prevalence is considerably high, the eradication rate of first line standard triple therapy has recently decreased down to 80%.5 Also second-line eradication failure rate reaches up to 15%–20%. However, there are no suggested empirical regimens for third-line eradication therapy in the revised Korean guideline at present.6 The main reason for this decreasing efficacy is assumed to be the increase in resistant strains to the key antibiotics such as clarithromycin.7,8 Maastricht IV/Florence guideline suggests antibiotic susceptibility test before deciding third-line regimen; however, this strategy is only available in some research institutes but not feasible in most medical centers in practice.9 Therefore empirical therapy excluding those antibiotics known to harbor high rates of resistance, such as metronidazole and macrolide, would be acceptable.

Levofloxacin is a quinolone antibiotics which has broad spectrum antibiotic effect against Gram-negative and positive bacteria. It is known to function by inhibiting protein gyrase and topoisomerase, therefore interfering with DNA replication. Recently, it has been suggested that levofloxacin-based rescue therapy would be an encouraging regimen for third-line eradication.10–13 On the other hand, several Korean researches have shown rather disappointing results with this regimen.14,15 However, those previous studies have enrolled either too small number of patients or patients with various indications including nonulcer dyspepsia. One the other hand, a recent Korean study reported near 80% of efficacy of levofloxacin-based sequential regimen as first-line treatment.16 Therefore, this study was designed to evaluate the efficacy and usefulness of levofloxacin-based third-line rescue therapy for H. pylori eradication in peptic ulcer disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Study population

This retrospective multicenter study involved adult patients older than 18 years who received third-line rescue H. pylori eradication therapy including levofloxacin after two consecutive failures of eradication for H. pylori-positive peptic ulcer disease in 14 secondary or tertiary medical centers in Korea between January 2002 and December 2014. Those who had eradication therapy for other indications than peptic ulcer disease were not included in this study. All the patients were primarily confirmed to have H. pylori infection by either rapid urease test or biopsy before the initiation of first-line therapy. The failure of the first- and second-line eradication therapy was confirmed by either 13C-urea breath test or rapid urease test/biopsy after each treatment. Final H. pylori eradication result after the third-line therapy was confirmed using 13C-urea breath test or rapid urease test 4 to 12 weeks after completion of the third-line therapy. Patients who did not undergo follow-up tests for H. pylori eradication result or those who did not complete the full duration of medication were excluded. The following variables were analyzed; age, sex, type of ulcer (gastric, duodenal, or gastroduodenal), composition of the H. pylori eradication regimen, duration of the medication, final H. pylori eradication status, time of the administration, and geographic area (Seoul, Incheon/Gyeonggi, Chungcheong, Gyeongsang, and Jeju). H. pylori eradication success was defined as a negative result in 13C-urea breath test or rapid urease test 4 to 12 weeks after completion of the medication.

This study was approved by the Public Institutional Review Board which complies with Helsinki Declaration. Patient consent was waived, because of the retrospective nature of this study.

2. Statistical analysis

For categorical variables, chi-square test or Fisher exact test was performed. Basically chi-square test was used and Fisher exact test was used only when more than 20% of expected frequencies were lower than 5. For continuous variables, Mann-Whitney test was performed. The p-values less than 0.05 were considered significant. All the statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS version 18.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

1. Baseline characteristics

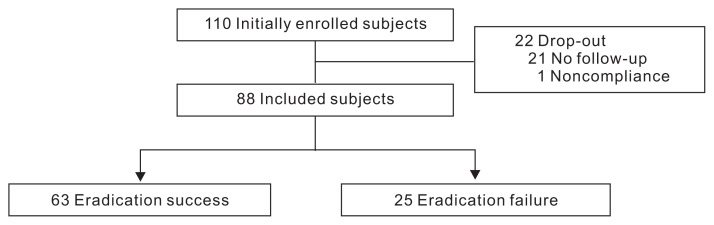

A total of 110 patients were initially enrolled in this study (Fig. 1). Among them, 22 were excluded because of either lack of the final confirmatory test or noncompliance. Twenty-one patients did not perform the 13C-urea breath test or rapid urease test after the treatment, and one did not complete the medication, taking only 4 days of medication under 7-day regimen. Therefore the remaining 88 patients were included in the analysis.

Fig. 1.

Schematic flowchart for patients in the study. Data from a total of 88 subjects, after exclusion of 21 who lacked follow-up visits after eradication and one who did not complete the full treatment duration, were reviewed retrospectively.

The male proportion was 60.2% and the median age was 57 (Table 1). Most of the patients were in their 50s and 60s, and living in Incheon/Gyeonggi province. More than 60% of the ulcers were gastric ulcers. Treatment durations were various, including 7 (35.2%), 10 (28.4%), and 14 days (36.4%). About one-third of patients were treated before 2010 and others after 2010. All the patients except one were administered with proton pump inhibitor (PPI)-amoxicillin-levofloxacin (PAL) and the other one with PPI-amoxicillin-clarithromycin-levofloxacin (PACL). There were no statistically significant differences in any baseline characteristics between the eradication success and failure groups.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| Characteristic | Eradication success (n=63) | Eradication failure (n=25) | Overall (n=88) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.321 | |||

| Male | 40 (63.5) | 13 (52.0) | 53 (60.2) | |

| Female | 23 (36.5) | 12 (48.0) | 35 (39.8) | |

| Age, yr | 58.0 (50.0–65.0) | 56.0 (48.5–64.0) | 57.0 (50.3–64.8) | 0.930 |

| 20–29 | 2 (3.2) | 1 (4.0) | 3 (3.4) | |

| 30–39 | 3 (4.8) | 3 (12.0) | 6 (6.8) | |

| 40–49 | 9 (14.3) | 2 (8.0) | 11 (12.5) | |

| 50–59 | 22 (34.9) | 8 (32.0) | 30 (34.1) | |

| 60–69 | 18 (28.6) | 7 (28.0) | 25 (28.4) | |

| 70–79 | 9 (14.3) | 2 (8.0) | 11 (12.5) | |

| 80–89 | 0 | 2 (8.0) | 2 (2.3) | |

| Geographic area | - | |||

| Seoul | 5 (7.9) | 2 (8.0) | 7 (8.0) | |

| Incheon/Gyeonggi | 42 (66.7) | 18 (72.0) | 60 (68.2) | |

| Chungcheong | 10 (15.9) | 2 (8.0) | 12 (13.6) | |

| Gyeongsang | 4 (6.3) | 0 | 4 (4.5) | |

| Jeju | 2 (3.2) | 3 (12.0) | 5 (5.7) | |

| Type of ulcer | - | |||

| Gastric ulcer | 41 (65.1) | 15 (60.0) | 56 (63.6) | |

| Duodenal ulcer | 19 (30.2) | 8 (32.0) | 27 (30.7) | |

| Gastroduodenal ulcer | 3 (4.8) | 2 (8.0) | 5 (5.7) | |

| Duration, day | 0.353 | |||

| 7 | 25 (39.7) | 6 (24.0) | 31 (35.2) | |

| 10 | 16 (25.4) | 9 (36.0) | 25 (28.4) | |

| 14 | 22 (34.9) | 10 (40.0) | 32 (36.4) | |

| Time | 0.496 | |||

| Before 2010 | 18 (28.6) | 9 (36.0) | 27 (30.7) | |

| After 2010 | 45 (71.4) | 16 (64.0) | 61 (69.3) | |

| Regimen | - | |||

| PAL | 62 (98.4) | 25 (100.0) | 87 (98.9) | |

| PACL | 1 (1.6) | 0 | 1 (1.1) |

Data are presented as number (%) or median (interquartile range).

PAL, proton pump inhibitor-amoxicillin-levofloxacin; PACL, proton pump inhibitor-amoxicillin-clarithromycin-levofloxacin.

2. Efficacy in H. pylori eradiation

Overall eradication rate was 71.6% (63/88). According to the treatment duration, there were no significant differences in eradication rates among the three different duration groups (7 days, 80.6% vs 10 days, 64.0% vs 14 days, 68.8%, p=0.353) (Table 2). Also the eradiation rates did not differ between those with different type of ulcers (gastric ulcer, 73.2% vs duodenal/gastroduodenal ulcer, 68.8%, p=0.655), geographic areas (Seoul metropolitan area, 70.1% vs other area, 76.2%, p=0.592), time of eradication (before 2010, 66.7% vs after 2010, 73.8%, p=0.496), and ages (<50 years, 70.0% vs 50 to 59 years, 73.3% vs 60 to 69 years, 72.0% vs ≥70 years, 69.2%, p=0.991).

Table 2.

Eradication Rates according to Treatment Duration, Type of Ulcer, Geographic Area, Duration of Treatment, and Age Group

| Eradication rate (%) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|

| Treatment duration, day | 0.353 | |

| 7 | 25/31 (81) | |

| 10 | 16/25 (64) | |

| 14 | 22/32 (69) | |

| Type of ulcer | 0.655 | |

| Gastric ulcer | 41/56 (73) | |

| Duodenal/gastroduodenal ulcer | 22/32 (69) | |

| Geographic area | 0.592 | |

| Seoul metropolitan area | 47/67 (70) | |

| Other areas | 16/21 (76) | |

| Time of administration | 0.496 | |

| Before 2010 | 18/27 (67) | |

| After 2010 | 45/61 (74) | |

| Age, yr | 0.991 | |

| <50 | 14/20 (70) | |

| 50–59 | 22/30 (73) | |

| 60–69 | 18/25 (72) | |

| ≥70 | 9/13 (69) |

DISCUSSION

Since the European Helicobacter Study Group was first founded in 1987, there have been multiple consensus meetings on how and when to treat H. pylori infection.9,17–19 Although some changes have been made so far, the recommended standard first- and second-line therapies have not been changed a lot. Nonetheless, their efficacy is gradually decreasing.20 According to the recently published Korean nationwide survey over the past 10 years, the eradication rates of standard first-line triple therapy has decreased down to 80% and that of second-line bismuth-containing quadruple therapy was 85% in 2010.5 Considering the unsatisfactory efficacy of standard eradication therapy, now is the time to establish rescue eradication regimen for multiple failures. In Korea, where the H. pylori prevalence is considerably high, the revised guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of H. pylori infection was recently published.6 However, none of current guidelines for H. pylori treatment suggest any empirical third-line regimen for refractory H. pylori infection. The European guideline suggests antimicrobial susceptibility testing after second failure,9 but this is not practically feasible in most of the cases because of the high expense and lack of facilities. Furthermore the yield of bacterial culture for H. pylori does not make 100%.21 Therefore establishment of empirical third-line treatment is warranted.

Although the activity of levofloxacin against H. pylori has been proved in vitro22 and it has been shown that quinolone and PPI have synergistic effect against H. pylori,23 recent studies demonstrate conflicting results with various eradication rates. A Spanish study with 1,000 patients who failed first-line eradication revealed per-protocol (PP) and intention-to-treat (ITT) eradication rate of 75.1% and 73.8%, respectively with 10 days PAL regimen, showing its potency as rescue therapy.24 Another Spanish study with the same regimen as third-line therapy has shown PP and ITT eradication rate of 66% and 60%.10 Also, a Taiwanese study using 7 days of PAL as secondary treatment showed PP and ITT eradication rate of 80.3% and 78.1%, confirming its satisfactory efficacy even in Asia.25 On the other hand, a Korean study using 10 days of PAL as third-line therapy showed rather disappointing result with only 57.1% of PP eradication rate.15 However this result is unreliable in the point that it enrolled only 14 patients. Another Korean study using 7 days of PPI-rifabutin-levofloxacin as third-line therapy showed moderate efficacy with PP and ITT eradication rate of 65% and 55.3%.26 Meanwhile, a Japanese randomized controlled trial using 7 days of PAL showed considerably low efficacy with PP and ITT eradication rate of 43.8% and 43.1%.27 All these conflicting results are assumed to be because of the various resistance rates. A previous prospective study in Italy reported 14% of primary resistance to levofloxacin.13 In a Korean study on levofloxacin resistance rate, there were no H. pylori strains with levofloxacin resistance among 1987 and 1994 strains, but 21.5% of 2003 strains showed levofloxacin resistance.28 More recent study reported the levofloxacin resistance rate of Korean H. pylori strains obtained between 2009 and 2012 to be as high as 28.1%.29 So far, many researchers have expressed skepticism on levofloxacin-based rescue therapy, because of the relatively high rate of levofloxacin resistance in Korea. However, the true efficacy of PAL as third-line eradication therapy has not evaluated yet. Thus it is worthwhile to evaluate the true efficacy because antibiotic susceptibility in vitro does not necessarily predict in vivo success in eradication.

Our study demonstrated overall eradication rate of 71.6% with the combination of PPI, amoxicillin, and levofloxacin for 7 to 14 days. This score is quite promising, considering that this regimen was given after two failures, even without susceptibility test. Taking into account that current eradication rates of the standard first- and second-line H. pylori eradication therapy are 80% and 85%, each,5 adding third-line therapy with PAL makes the cumulative eradication rate over 99%. Our result showed better efficacy with levofloxacin-based eradication regimen compared to the above mentioned previous Korean studies.15,26 The reason for this is unclear but it could be because of different numbers of patients enrolled and different indications included in the studies. Previous studies enrolled less than one half of the number enrolled in current study. Also, the enrolled patients were under various indications including peptic ulcer, early gastric cancer, family history of gastric cancer, and atrophic gastritis/intestinal metaplasia, whereas current study enrolled patients with rather unified indication of peptic ulcer only. Therefore, at least for those with H. pylori-positive peptic ulcer, levofloxacin-based triple therapy could be recommended as empirical third-line rescue therapy.

In this study, there were no differences in treatment efficacy according to treatment duration, type of ulcer, geographic area, time of therapy, and age group. Previously it has been reported that the eradication rate of 10-day PAL regimen was higher than that of 7-day PAL regimen.30 However, current study did not show any difference in eradication rates according to treatment duration. Furthermore, 7-day regimen showed the highest efficacy, although without statistical significance. Nevertheless, these results should be further confirmed in a larger population, as each group involved relatively small number of patients. In this study, all the patients except only one received PAL regimen and the one received PACL regimen, in whom the eradication was successful. Considering all the patients’ first-line regimen was standard triple therapy including clarithromycin and amoxicillin, the successful eradication by PACL is assumed to be because of levofloxacin.

Some studies have evaluated other alternative regimens for third-line eradication, such as rifabutin- and sitafloxacin-based regimens. Rifabutin is one of the antibiotics with outstanding activity against H. pylori in vitro and its previously reported primary resistance rate is considerably low, ranging from 0.2% to 1.4%.31 Rifabutin-based therapy has shown good efficacy in a Korean study showing 71.4% of PP eradication rate.15 However, usage of rifabutin is limited due to the high cost and potential myelotoxicity.32 Also it would be better to be saved to prevent resistance, as rifabutin is useful antibiotics against tuberculosis, which is considerably frequent and troublesome infection in Korea. Sitafloxacin, the newly developed quinolone antibiotics, is known to be highly effective in H. pylori eradication with a low minimal inhibitory concentration.22 It has shown pretty good efficacy in Japan with >70% of eradication rate.27,33 However, at the moment its use in practice is not yet available in Korea.

Among our study population, only one patient failed to complete the full duration of medication and no serious adverse reaction was reported. A previous meta-analysis also revealed better compliance rate of levofloxacin-based therapy compared with that of bismuth-containing quadruple therapy.34 The high compliance rate is assumed to be because of the simple administration schedule which is only twice a day. Therefore levofloxacin-based triple therapy seems safe and tolerable.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated relatively good efficacy of levofloxacin-based third-line rescue therapy for H. pylori eradication in peptic ulcer disease. Therefore we suggest that levofloxacin-based triple therapy would constitute an encouraging empirical strategy for persistent H. pylori infection in peptic ulcer patients after multiple eradication failures.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by a grant (14172MFDS178) from Ministry of Food and Drug Safety in 2014. Author’s contribution: J.H.L. and S.G.K. carried out study design, data analysis, and interpretation. J.H.L. carried out manuscript drafting. J.H.S., J.J.H., D.H.L., J.P.H., S.J.H., J.H.K., S.W.J., G.H.K., K.N.S., W.G.S., T.H.K., S.M.K., I.K.C., H.S.K., H.U.K., J.L., and J.G.K. participated in manuscript revision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.NIH Consensus Conference. Helicobacter pylori in peptic ulcer disease: NIH consensus development panel on Helicobacter pylori in peptic ulcer disease. JAMA. 1994;272:65–69. doi: 10.1001/jama.1994.03520010077036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suerbaum S, Michetti P. Helicobacter pylori infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1175–1186. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marshall BJ, Goodwin CS, Warren JR, et al. Prospective double-blind trial of duodenal ulcer relapse after eradication of Campylobacter pylori. Lancet. 1988;2:1437–1442. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(88)90929-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marshall BJ, Warren JR. Unidentified curved bacilli in the stomach of patients with gastritis and peptic ulceration. Lancet. 1984;1:1311–1315. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(84)91816-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shin WG, Lee SW, Baik GH, et al. Eradication rates of Helicobacter pylori in Korea over the past 10 years and correlation of the amount of antibiotics use: nationwide survey. Helicobacter. 2016;21:266–278. doi: 10.1111/hel.12279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim SG, Jung HK, Lee HL, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection in Korea, 2013 revised edition. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:1371–1386. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mégraud F. H pylori antibiotic resistance: prevalence, importance, and advances in testing. Gut. 2004;53:1374–1384. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.022111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee JH, Shin JH, Roe IH, et al. Impact of clarithromycin resistance on eradication of Helicobacter pylori in infected adults. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:1600–1603. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.4.1600-1603.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain CA, et al. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection: the Maastricht IV/Florence Consensus Report. Gut. 2012;61:646–664. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gisbert JP, Castro-Fernández M, Bermejo F, et al. Third-line rescue therapy with levofloxacin after two H. pylori treatment failures. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:243–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gisbert JP, Gisbert JL, Marcos S, Moreno-Otero R, Pajares JM. Third-line rescue therapy with levofloxacin is more effective than rifabutin rescue regimen after two Helicobacter pylori treatment failures. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:1469–1474. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tursi A, Picchio M, Elisei W. Efficacy and tolerability of a third-line, levofloxacin-based, 10-day sequential therapy in curing resistant Helicobacter pylori infection. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2012;21:133–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gatta L, Zullo A, Perna F, et al. A 10-day levofloxacin-based triple therapy in patients who have failed two eradication courses. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:45–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee JH, Hong SP, Kwon CI, et al. The efficacy of levofloxacin based triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2006;48:19–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jeong MH, Chung JW, Lee SJ, et al. Comparison of rifabutin- and levofloxacin-based third-line rescue therapies for Helicobacter pylori. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2012;59:401–406. doi: 10.4166/kjg.2012.59.6.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee H, Hong SN, Min BH, et al. Comparison of efficacy and safety of levofloxacin-containing versus standard sequential therapy in eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection in Korea. Dig Liver Dis. 2015;47:114–118. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2014.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malfertheiner P, Mégraud F, O’Morain C, et al. Current European concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection: the Maastricht Consensus Report. The European Helicobacter Pylori Study Group (EHPSG) Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1997;9:1–2. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199701000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Malfertheiner P, Mégraud F, O’Morain C, et al. Current concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection: the Maastricht 2–2000 Consensus Report. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:167–180. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain C, et al. Current concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection: the Maastricht III Consensus Report. Gut. 2007;56:772–781. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.101634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gong EJ, Yun SC, Jung HY, et al. Meta-analysis of first-line triple therapy for helicobacter pylori eradication in Korea: is it time to change? J Korean Med Sci. 2014;29:704–713. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2014.29.5.704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Megraud F, O’Morain C, Malfertheiner P, et al. Technical annex: tests used to assess Helicobacter pylori infection. Gut. 1997;41(Suppl 2):S10–S18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sánchez JE, Sáenz NG, Rincón MR, Martín IT, Sánchez EG, Martínez MJ. Susceptibility of Helicobacter pylori to mupirocin, oxazolidinones, quinupristin/dalfopristin and new quinolones. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2000;46:283–285. doi: 10.1093/jac/46.2.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tanaka M, Isogai E, Isogai H, et al. Synergic effect of quinolone antibacterial agents and proton pump inhibitors on Helicobacter pylori. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2002;49:1039–1040. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkf055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gisbert JP, Pérez-Aisa A, Bermejo F, et al. Second-line therapy with levofloxacin after failure of treatment to eradicate helicobacter pylori infection: time trends in a Spanish Multicenter Study of 1000 patients. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;47:130–135. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318254ebdd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chuah SK, Hsu PI, Chang KC, et al. Randomized comparison of two non-bismuth-containing second-line rescue therapies for Helicobacter pylori. Helicobacter. 2012;17:216–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2012.00937.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yun SP, Seon HG, Ok CS, et al. Rifaximin plus levofloxacin-based rescue regimen for the eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Gut Liver. 2012;6:452–456. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2012.6.4.452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murakami K, Furuta T, Ando T, et al. Multi-center randomized controlled study to establish the standard third-line regimen for Helicobacter pylori eradication in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 2013;48:1128–1135. doi: 10.1007/s00535-012-0731-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim JM. Antibiotic resistance of Helicobacter pylori isolated from Korean patients. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2006;47:337–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee JW, Kim N, Kim JM, et al. Prevalence of primary and secondary antimicrobial resistance of Helicobacter pylori in Korea from 2003 through 2012. Helicobacter. 2013;18:206–214. doi: 10.1111/hel.12031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Di Caro S, Fini L, Daoud Y, et al. Levofloxacin/amoxicillin-based schemes vs quadruple therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication in second-line. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:5669–5678. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i40.5669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gisbert JP, Calvet X. Review article: rifabutin in the treatment of refractory Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:209–221. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04937.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gisbert JP, Calvet X, Bujanda L, Marcos S, Gisbert JL, Pajares JM. ‘Rescue’ therapy with rifabutin after multiple Helicobacter pylori treatment failures. Helicobacter. 2003;8:90–94. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5378.2003.00128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sugimoto M, Sahara S, Ichikawa H, Kagami T, Uotani T, Furuta T. High Helicobacter pylori cure rate with sitafloxacin-based triple therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42:477–483. doi: 10.1111/apt.13280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saad RJ, Schoenfeld P, Kim HM, Chey WD. Levofloxacin-based triple therapy versus bismuth-based quadruple therapy for persistent Helicobacter pylori infection: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:488–496. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]