Abstract

Objective

To examine trends in prescription of cough medicines over the period 2002–2015 in children aged 1 month to 12 years admitted to Kenyan hospitals with cough, difficulty breathing or diagnosed with a respiratory tract infection.

Methods

We reviewed hospitalisation records of children included in four studies providing cross‐sectional prevalence estimates from government hospitals for six time periods between 2002 and 2015. Children with an atopic illness were excluded. Amongst eligible children, we determined the proportion prescribed any adjuvant medication for cough. Active ingredients in these medicines were often multiple and were classified into five categories: antihistamines, antitussives, mucolytics/expectorants, decongestants and bronchodilators. From late 2006, guidelines discouraging cough medicine use have been widely disseminated and in 2009 national directives to decrease cough medicine use were issued.

Results

Across the studies, 17 963 children were eligible. Their median age and length of hospital stay were comparable. The proportion of children who received cough medicines shrank across the surveys: approximately 6% [95% CI: 5.4, 6.6] of children had a prescription in 2015 vs. 40% [95% CI: 35.5, 45.6] in 2002. The most common active ingredients were antihistamines and bronchodilators. The relative proportion that included antihistamines has increased over time.

Conclusions

There has been an overall decline in the use of cough medicines among hospitalised children over time. This decline has been associated with educational, policy and mass media interventions.

Keywords: cough medicines, respiratory tract infection, hospitalised children, prescription practices, Kenya

Abstract

Objectif

Examiner les tendances de la prescription de médicaments contre la toux durant la période de 2002 à 2015 chez les enfants de 1 mois à 12 ans admis dans les hôpitaux kenyans avec de la toux, des difficultés respiratoires ou ayant reçu un diagnostic d'infection des voies respiratoires.

Méthodes

Nous avons examiné les dossiers d'hospitalisation des enfants inclus dans quatre études fournissant des estimations transversales de la prévalence dans les hôpitaux publics pour 6 périodes entre 2002 et 2015. Les enfants atteints d'une maladie atopique ont été exclus. Parmi les enfants admissibles, nous avons déterminé la proportion ayant été prescrite tout médicament adjuvant contre la toux. Les principes actifs de ces médicaments étaient souvent multiples et ont été classés en cinq catégories: antihistaminiques, antitussifs, mucolytiques/expectorants, décongestionnants et bronchodilatateurs. Depuis la fin de 2006, des directives découragent l'usage de médicaments contre la toux ont été largement diffusées et en 2009, des directives nationales visant à diminuer l'utilisation des médicaments pour la toux ont été publiées.

Résultats

Au cours des études, 17 963 enfants étaient admissibles. Leur âge médian et la durée de leur hospitalisation étaient comparables. La proportion d'enfants qui ont reçu des médicaments contre la toux a chuté dans les enquêtes: environ 6% [IC95%: 5,4 ‐ 6,6] des enfants avaient une ordonnance en 2015 contre 40% [IC95%: 35,5 ‐ 45.6] en 2002. Les principes actifs les plus courants étaient des antihistaminiques et des bronchodilatateurs. La proportion relative comprenant des antihistaminiques a augmenté au fil du temps.

Conclusions

Il y a eu une baisse générale de l'utilisation de médicaments contre la toux chez les enfants hospitalisés au fil du temps. Ce déclin a été associé à des interventions éducatives, politiques et de média de masse.

Abstract

Objetivo

Examinar las tendencias en la prescripción de medicamentos para la tos dentro del periodo entre 2002 y 2015 en niños con edades entre 1 mes y 12 años admitidos en hospitales de Kenia con tos, dificultad respiratoria o diagnosticados con una infección del tracto respiratorio.

Métodos

Hemos revisado las historias clínicas de niños incluidos en cuatro estudios, obteniendo un cálculo de prevalencia croseccional de hospitales gubernamentales dentro de 6 periodos de tiempo entre el 2002 y el 2015. Se excluyeron los niños con una enfermedad atópica. Entre aquellos elegibles, determinamos la proporción prescrita de cualquier medicamento para la tos. Los ingredientes activos en estos medicamentos eran a menudo múltiples y se clasificaron en cinco categorías: antihistamínicos, antitusivos, mucolíticos/expectorantes, decongestionantes y broncodilatadores. Desde finales del 2006, las guías que desaconsejan el uso de medicamentos para la tos han sido ampliamente diseminadas y en el 2009 se lanzaron directivas nacionales para disminuir el uso de medicamentos para la tos.

Resultados

A lo largo de todos los estudios 17,963 niños fueron elegible. Se compararon la mediana de edad y el tiempo de hospitalización. La proporción de niños que recibieron medicamentos para la tos disminuyó a lo largo de los estudios: aproximadamente un 6% [IC 95% 5.4, 6.6] de los niños tenían una prescripción en el 2015 vs. 40% [IC 95% 35.5, 45.6] en el 2002. Los ingredientes activos más comunes eran antihistamínicos y broncodilatadores. La proporción relativa que incluía antihistamínicos ha disminuido a lo largo del tiempo.

Conclusiones

Ha habido una disminución general en el uso de medicamentos para la tos entre los niños hospitalizados a lo largo del tiempo. Esta disminución se ha asociado a intervenciones educativas, políticas y de medios de comunicación masiva.

Introduction

Cough is a common symptom in children presenting with respiratory tract infections. It tends to cause anxiety to caregivers, discomfort to the child 1, and physicians are usually under pressure to prescribe medication for symptomatic relief contrary to treatment guidelines 2, 3, 4. Medications used include mucolytic agents (to reduce the thickness of mucus), decongestants and antitussives (to suppress cough). Cough suppression may lead to accumulation of secretions, airway obstruction and hypoxaemia 5, 6. Some cough medications contain active ingredients that have been associated with serious adverse reactions including arrhythmias, behavioural disturbances, respiratory depression and even death 5, 7, 8. Many studies, mainly in Europe and North America, have shown widespread use of cough mixtures, mainly decongestants and antitussive medications 9 and report that up to 6% of all visits to the emergency department could be secondary to adverse drug events in children under 12 years using cough medicines 10.

There have been varied efforts to improve care and guideline compliance for treatment of respiratory infections in Kenya over a number of years. These include the initial introduction and scale up of the Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) from 1999, introduction and scale up of Emergency Triage Assessment and Treatment plus admission care (ETAT+) training targeting hospital‐based care from 2006 and efforts at disseminating policy through the media (2009) to discourage prescription of cough mixtures to children 11, 12. There have, however, been few reports on the use of cough medication in children in the sub‐Saharan region, and most have examined their use in outpatient settings 13. Three prior studies in Kenyan hospitals using standardised methods 14, 15, 16, 17 and ongoing inpatient surveillance in paediatric wards in 13 Kenyan county hospitals 18 present an opportunity to examine trends in prescription of cough mixtures over the period 2002–2015 in ill children admitted to hospital for whom risks of adverse effects may be higher. Although behaviour change at scale may take time to manifest, it is unusual to have longitudinal data from a low‐income setting. This report presents such data that may be of wider relevance given current concerns on how to reduce unnecessary antibiotic use.

Methods

Setting

The study uses data collected using a consistent method as part of four research studies in Kenya that provide data from six time points between 2002 and 2015 15, 16, 17, 18, 19. These studies were carried out in hospital facilities located in a district's (now county) main town, which provide first referral care. Surveys were conducted in collaboration with the Ministry of Health as part of research examining the quality of paediatric care. Facilities across Kenya were purposefully sampled to meet the needs of the particular survey (Table 1). Children in these facilities are expected to be under the care of general medical officers and clinical officers (non‐physician clinicians) under the supervision of a paediatrician who is responsible for inpatient prescribing, one focus of the surveys. In all the surveys, a similar approach to training data collectors to review medical records of children after discharge was used (comprising workshops, pilot exercises and use of standard operating procedures), similar data elements were collected, and data collection was supervised with procedures for quality assurance employed. We have previously shown that collecting these data from archived records provides the same results as collecting data while children are admitted 17. The data used in the analyses reported included demographic data, documented clinical signs and symptoms, vital signs, the admission drugs prescribed and the clinical outcome 20. In an effort to standardise the type of care being evaluated, we excluded one facility in the 2013–2015 survey as care is provided by non‐physician clinicians, there are no qualified doctors and it is a large demonstration health centre with few inpatient beds rather than being a county referral hospital. A summary of the surveys and the hospital selection process is shown in Table 1. All studies were approved by the Kenyan Ministry of Health and had ethical approval from the Kenya Medical Research Institute.

Table 1.

Key features of the clinical studies that collected data from medical records of children discharged after admission with acute non‐surgical illnesses

| Study name | District hospital study | Eight district hospital study | Sircle study | The clinical information network | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Period of data used | 2002 15 | 2006 (Pre‐intervention) 28, 29 | 2008 (Post‐intervention) 28, 29 | 2012 16, 19 | 2013a 18, 30 | 2015a 18, 30 |

| Number of Hospitals | 14 | 8 | 8 | 22 | 13 | 13 |

| Total cases examined in survey | 641 | 8212 | 6624 | 1298 | 13 081 | 14 639 |

| Case selection process | Convenience sample of recently hospitalised children | Simple Random sampling of paediatric inpatient records over six months period prior to survey | Convenience sample of hospital inpatient records from most recent discharges | Comprehensive sample of all paediatric hospital inpatient records from the most recent discharges. Surgical cases and newborns are excluded | ||

| Intervention prior to the study | None | None | Provision of training on clinical guidelines, feedback and supportive supervision | None | (Ongoing Intervention) Three monthly feedback on quality of medical documentation and adherence to guidelines (no specific feedback on cough medicines) | |

| Number meeting inclusion criteria | 383 | 2166 | 2199 | 891 | 6140 | 6157 |

Included the first six months of enrolment into the study for each facility in the 2013 period and six months of 2015 (June–November).

Study population and data analysis

We used de‐identified data from all children from 1 month to 12 years admitted with symptoms of cough or difficulty in breathing or a diagnosis of an upper or lower respiratory tract infection based on the ICD 10 criteria 21 (Table S1). The analysis excluded children with a diagnosis indicating an atopic illness, as these children may have been given antihistamines as part of their treatment (Table S2). We included children with a diagnosis of asthma so as to capture the (inappropriate) use of oral bronchodilators, which is currently not recommended due to the adverse effects. Inhaled bronchodilators are the treatment of choice for asthma in children 22. Amongst eligible children, we determined the proportion prescribed any adjuvant medication for cough. To do this, we matched the names of each child's prescribed drugs against published lists of medicines available in Kenya and formularies to determine their active ingredients. We classified active ingredients in these medicines (referred to as a group as cough medicines) into five categories: antihistamines, antitussives, mucolytics/expectorants, decongestants and bronchodilators 23 (Table S3). The data are summarised as the proportion of children admitted with a respiratory illness with at least one cough medicine calculating 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) around this estimate and presenting the result graphically. We further explored the pattern of active ingredients used over time using graphical methods. In these latter analyses, each active ingredient was counted such that a medicine containing three active compounds would contribute 1 count in each of three categories of ingredients.

Ethical approval

The findings reported here derive from data collected in three studies that were individually approved by The KEMRI Scientific and Ethics Review committees.

Results

The median age and length of the hospital stay of the participants were comparable across the data sets. However, children included less frequently had cough in later studies (2013 and 2015), and fever was more prevalent in some surveys (2006 and 2008). Mortality also varied across the studies from 4.7% to 10.2%. Table 2 summarises data on the populations of children included in each study.

Table 2.

Demographic Characteristics across the survey data sets

| Survey | 2002 N = 383 | 2006 N = 2166 | 2008 N = 2199 | 2012 N = 891 | 2013 N = 6140 | 2015 N = 6157 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age in months (IQR) | 12 (5–28.25) | 12 (6–27) | 12 (6–24) | 14 (8–27) | 14 (7–22) | 16 (8–30) |

| Presence of fever (%) | 303 (79.11) | 1625/1675a (97) | 1825/2085a (87.5) | 684 (76.8) | 4653 (75.8) | 4411 (71.6) |

| Presence of cough (%) | 316 (82.51) | 1643/1693a (97) | 1751/2075a (84.4) | 667 (74.9) | 3958 (64.5) | 3743 (60.8) |

| Average length of stay days (IQR) | 3 (2–5) | 3 (2–6) | 3 (2–5) | 3 (2–6) | 3 (2–6) | 3 (2–6) |

| Mortality rate (%) | 22/383 (5.74) | 162/2106 (7.7) | 221/2162a (10.2) | 42 (4.7) | 324 (5.3) | 353 (5.7) |

Missing values were excluded in the computation, hence different denominators from the sample size.

Cough medicine prescription trends

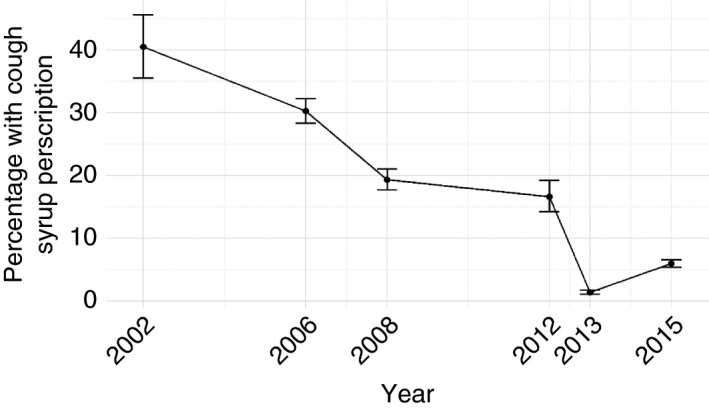

The proportion of children who received cough medicines diminished across the surveys with approximately 6% [95% CI: 5.4, 6.6] having a prescription in 2015 vs. 40% [95% CI: 35.5, 45.6] 13 years earlier. There was a marked decrease between 2012 and 2013/14; however, we note a small increase in their use between the 2013 and 2015 surveys as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Percentage of cough medicine prescriptions across the various studies.

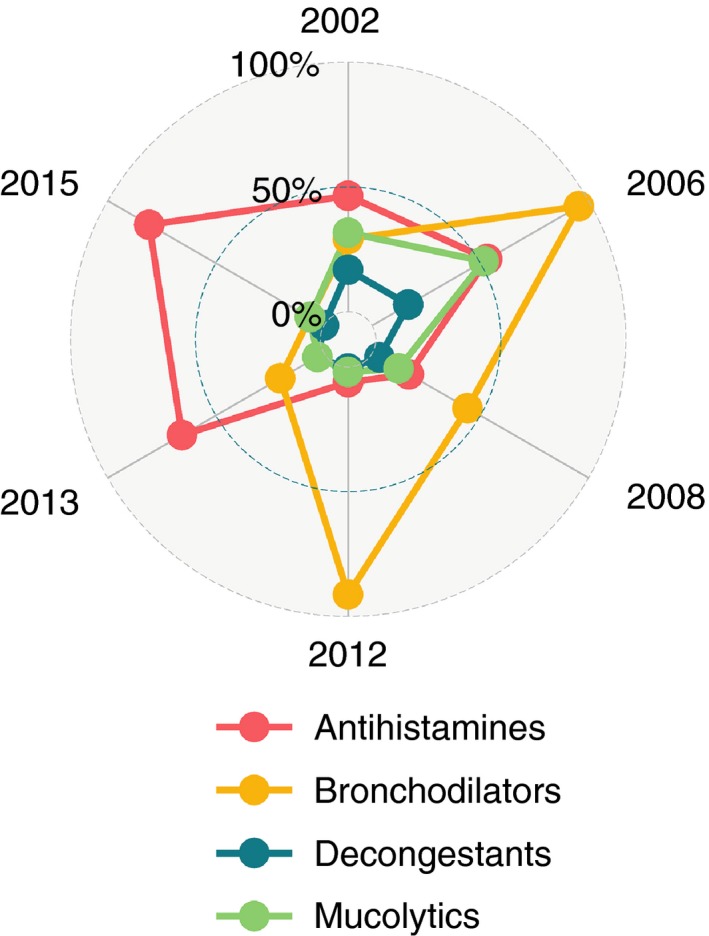

Cough medicine contents

Across the surveys, the most common active ingredients in prescribed cough medicines were antihistamines and bronchodilators. Between 2006 and 2012, cough medicines containing oral bronchodilators constituted the bulk of prescriptions. Amongst children prescribed a cough medicine, the proportion that include antihistamines as active ingredients increased over time, constituting over half of the prescriptions in the 2013 and 2015 surveys. Prescription of decongestant‐containing medicines remained relatively infrequent across the studies (Figure 2). The prescriptions containing antitussives were very few and are not included in the figure.

Figure 2.

Radar plot describing the proportion of all active ingredients in cough medicines that were either antihistamines, bronchodilators, decongestants or mucolytics for a given year.

Discussion

There has been a general decline in the prescription rates for cough medicines across the fourteen years from 40% in 2002 to 6% in 2015 for children admitted to general district (now county) hospitals with cough, difficulty breathing or diagnosed with an upper respiratory infection. This is despite the low cost of cough medicines and continuing aggressive marketing by manufacturers in Kenya, which has been identified as one of the reasons why cough medicines are prescribed. It has also been suggested that health workers have a poor understanding of the ingredients in cough medicines 13. This suggests that marketing or some perceived benefit of active ingredients where they are known might influence changes in the pattern of active ingredients over time. Accompanying an overall decline in cough medicine prescribing was a shift across the surveys first towards bronchodilator and then towards antihistamine‐containing cough medicines. This may be due to more effective marketing of newer generation antihistamine medications said to have better safety profiles 24. In earlier surveys, children prescribed a cough medicine containing bronchodilators may often have been prescribed inhaled beta‐agonists as specific treatment too (unpublished observation). The later decline in use of cough medicines containing bronchodilators may, we speculate, be linked to efforts to improve awareness of the appropriate use of inhaled bronchodilators for asthma and that oral bronchodilators are of limited effectiveness.

Across the time period spanning the surveys and the decline in cough medicine use, there have been a number of initiatives that may have influenced prescribing habits (Table 3). In addition to these, there has been an improvement in clinical staffing numbers and the cadre of clinical staff in charge of the paediatric wards has slowly changed. In 2002, with few paediatricians in the country, most inpatient paediatric care was led by clinical officers (non‐physician clinicians) supervised by general medical officers. However, by the 2013–2015 survey, inpatient paediatric care in county hospitals, including the 13 in this study, was often led by a consultant paediatrician assisted by several intern medical officers and sometimes a general medical officer 25. Many of these medical officers and paediatricians were trained in use of and have access to national guidelines 26, with the training typically emphasising that cough medicines are contraindicated. We speculate therefore that some of the decline in use of cough medicines for the inpatient population is attributable to greater presence in hospitals of junior physicians and consultant paediatricians educated not to use cough medicines. Such staff would also have been target recipients of updated pneumonia guideline dissemination after the 2013 revisions when a notable decrease in cough medicine use occurred. (Figure 1) Interestingly, a review of the prescriptions from the excluded health facility, where all patient care is provided by non‐physician clinicians, revealed a larger number of cough medicine prescriptions amongst those admitted for care for pneumonia, averaging about 14% for the two periods (2013 and 2015).

Table 3.

Major Interventions that may have contributed to a decline in cough medicine prescriptions

| Year | Intervention | Description of intervention |

|---|---|---|

| 1995 4, 31 | Integrated management of childhood illness (IMCI) |

Improving the case management of common illnesses including respiratory illnesses. Gave clear guidelines on how to effectively handle children with cough highlighting potential harm in cough mixtures. |

| 2006 11, 26, 32 | Emergency Triage Assessment and Treatment pus admission care (ETAT+) |

Guidelines to assist in classification and treatment of children presenting with cough with wide‐scale national dissemination from 2008 onwards. In particular, 10 000 copies of guidelines were disseminated in 2010, and following a national pneumonia treatment policy review in 2013, 12 000 copies of updated guidelines were disseminated in 2013 and presented to over 200 paediatricians at the national paediatric conference. The guidelines and training clearly discourage the use of cough mixtures and use of oral bronchodilator medications |

| 2009 12 | Ministry of Health |

Through the pharmacy and poisons board issued a policy directive on the use of cough remedies. Disseminated through print media |

| 2009 33 | Private Hospitals ban use of cough mixtures i∝n children | Largest Kenyan private children's hospital and a university hospital remove cough syrups from their hospital formularies and pharmacies, an event covered by national print media |

This study had a number of limitations. Purposive sampling of hospitals was employed for each survey, and there was no pre‐specified aim to track use of unnecessary medicines across time. Each study also provided different samples sizes for analysis, and the data were collected by different teams in the individual studies even though similar tools were used. Based on the data collected, we are unable to determine the doses of the medicines prescribed, the frequency of administration or whether any adverse events occurred as a result of the prescriptions. Furthermore, it is possible that some prescriptions for cough medicines were not recorded in hospital records but given directly to parents. In the 2013–2015 survey, we noted an increase in the prescription of cough medicines between the two six‐month periods sampled. A reduction in levels of missing data on other parameters of interest within the clinical information network has been noted over this period 27. An improvement in the capture of data on cough medicines may therefore be contributing to their apparent increase in use.

Despite these limitations, we feel that the decline in the prescription of cough medicines observed across surveys in hospitalised children in Kenya is likely to reflect a true change in practice over a period of 14 years. We suggest that reducing exposure of already sick hospitalised children to their potential adverse events is likely therefore to have helped improve patient safety and reduced healthcare costs. As most cough remedies may be provided to ambulant children as over the counter or outpatient prescriptions, examination of cough mixture use among these groups of children would also be useful to provide a more complete picture of the situation in Kenya and other countries.

Conclusion

There has been an overall decline in the use of cough medicines among hospitalised children across Kenyan hospitals over time. This decline has been associated with educational, policy and mass media interventions and an expansion of the physician and specialist paediatric workforce. We believe the findings help demonstrate the value of long‐term surveillance of prescribing habits that may be of particular value in an era when there is increasing concern around rational treatment use and stewardship.

Supporting information

Table S1. ICD 10 classification of upper and lower respiratory tract conditions presenting with cough.

Table S2. ICD 10 classification of respiratory allergic conditions.

Table S3. Classification of common ingredients in cough mixtures.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Ministry of Health who gave permission for the various studies that were included in this article. We also thank the hospital paediatricians and clinical teams on all the paediatric wards who provide care to the children for whom this project is designed. This work is published with the permission of the Director of KEMRI and was supported by funds from The Wellcome Trust. The funders had no role in drafting or submitting this manuscript.

References

- 1. Cornford CS, Morgan M, Ridsdale L. Why do mothers consult when their children cough? Fam Pract 1993: 10: 193–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee . Pocket Book of Hospital Care for Children: Guidelines for the Management of Common Childhood Illnesses. 2. World Health Organization: Geneva; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ministry of Health . Basic Paediatric Protocols for ages up to 5 years Nairobi: KEMRI‐Wellcome Trust Research Programme, Kenya Paediatric Association; 2016. 4th (Available from: http://idoc-africa.org/images/documents/2016/Basic_Paediatric_Protocol_2016/MAY%2023rd%20BPP%202016%20SA.pdf) [updated February 2016; 5 May 2016].

- 4. Gove S. Integrated management of childhood illness by outpatient health workers: technical basis and overview. The WHO Working Group on Guidelines for Integrated Management of the Sick Child. Bull World Health Organ 1997: 75(Suppl 1): 7–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dolansky G, Rieder M. What is the evidence for the safety and efficacy of over‐the‐counter cough and cold preparations for children younger than six years of age? Paediat Child Health 2008: 13: 125–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Drugs . Use of codeine‐ and dextromethorphan‐containing cough remedies in children. Pediatrics 1997: 99: 918–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chang CC, Cheng AC, Chang AB. Over‐the‐counter (OTC) medications to reduce cough as an adjunct to antibiotics for acute pneumonia in children and adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014: 3: Cd006088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. World Health Organization . The Rational Use of Drugs ‐ Report of the Conference of Experts, Nairobi 25–29 November 1985. World Health Organization: Geneva, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vernacchio L, Kelly JP, Kaufman DW, Mitchell AA. Cough and cold medication use by US children, 1999‐2006: results from the slone survey. Pediatrics 2008: 122: e323–e329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schaefer MK, Shehab N, Cohen AL, Budnitz DS. Adverse events from cough and cold medications in children. Pediatrics 2008: 121: 783–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gove S, Tamburlini G, Molyneux E, Whitesell P, Campbell H. Development and technical basis of simplified guidelines for emergency triage assessment and treatment in developing countries. WHO Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) Referral Care Project. Arch Dis Child 1999: 81: 473–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kenya Pharmacy and Poisons Board . Children's over‐the‐counter cough and cold medicines: advice to parents. Department of Pharmacovigilance; 2014. (Available from: http://pharmacyboardkenya.org/?page_id=399) [Accessed 16 October 2016].

- 13. Kigen G, Busakhala N, Ogaro F et al . A review of the ingredients contained in over the counter (OTC) cough syrup formulations in Kenya. Are they harmful to infants?. PLoS ONE 2015: 10: e0142092. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0142092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ayieko P, Ntoburi S, Wagai J et al A multifaceted intervention to implement guidelines and improve admission paediatric care in Kenyan district hospitals: a cluster randomised trial. PLoS Med 2011;8: e1001018. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. English M, Esamai F, Wasunna A et al Assessment of inpatient paediatric care in first referral level hospitals in 13 districts in Kenya. Lancet 2004: 363: 1948–1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gathara D, Nyamai R, Were F et al Moving towards routine evaluation of quality of inpatient pediatric care in Kenya. PLoS ONE 2015: 10: e0117048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mwaniki P, Ayieko P, Todd J, English M. Assessment of paediatric inpatient care during a multifaceted quality improvement intervention in Kenyan District Hospitals – use of prospectively collected case record data. BMC Health Services Res 2014: 14: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ayieko P, Ogero M, Makone B et al Characteristics of admissions and variations in the use of basic investigations, treatments and outcomes in Kenyan hospitals within a new Clinical Information Network. Arch Dis Child 2015: 101: 223–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Aluvaala J, Nyamai R, Were F et al Assessment of neonatal care in clinical training facilities in Kenya. Arch Dis Child 2015: 100: 42–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. English M, Ntoburi S, Wagai J et al An intervention to improve paediatric and newborn care in Kenyan district hospitals: understanding the context. Implement Sci 2009: 4: 42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. World Health Organisation . International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems. World Health Organisation: Geneva, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Horak F, Doberer D, Eber E et al Diagnosis and management of asthma – Statement on the 2015 GINA Guidelines. Wien Klin Wochenschr 2016: 00: 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Australian Government Department of Health . Cough and cold medicines for children Australia; 2015. (Available from: https://www.tga.gov.au/node/1056) [updated Aug 2015; 1 Sept 2015].

- 24. Ten Eick AP, Blumer JL, Reed MD. Safety of antihistamines in children. Drug Saf 2001: 24: 119–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ministry of Health . National Human Resources for Health Strategic Plan 2009–2012. Ministry of Health: Nairobi; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 26. English M, Wamae A, Nyamai R, Bevins B, Irimu G. Implementing locally appropriate guidelines and training to improve care of serious illness in Kenyan hospitals: a story of scaling‐up (and down and left and right). Arch Dis Child 2011: 96: 285–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tuti T, Bitok M, Malla L et al Improving documentation of clinical care within a clinical information network: an essential initial step in efforts to understand and improve care in Kenyan hospitals. BMJ Global Health 2016: 1: e000028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mwaniki P, Ayieko P, Todd J, English M. Assessment of paediatric inpatient care during a multifaceted quality improvement intervention in Kenyan district hospitals–use of prospectively collected case record data. BMC Health Serv Res 2014: 14: 312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ayieko P, Ntoburi S, Wagai J et al A multifaceted intervention to implement guidelines and improve admission paediatric care in Kenyan district hospitals: a cluster randomised trial. PLoS Med 2011: 8: e1001018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tuti T, Bitok M, Paton C et al Innovating to enhance clinical data management using non‐commercial and open source solutions across a multi‐center network supporting inpatient pediatric care and research in Kenya. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2015: 23: 184–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. World Health Organisation . A guide to identifying necessary adaptations of clinical policies and guidelines, and to adapting the charts and modules for the WHO/UNICEF course. Development DoCaAHa: Geneva, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 32. English M, Gathara D, Mwinga S et al Adoption of recommended practices and basic technologies in a low‐income setting. Arch Dis Child 2014: 99: 452–456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gatonya Gathura and Mike Mwaniki Hospitals ban children's cough syrup. Daily Nation. 2009 11th March 2009; Sect. News.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. ICD 10 classification of upper and lower respiratory tract conditions presenting with cough.

Table S2. ICD 10 classification of respiratory allergic conditions.

Table S3. Classification of common ingredients in cough mixtures.