Abstract

One of the main effects of the endocannabinoid system in the brain is stress adaptation with presynaptic endocannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1 receptors) playing a major role. In the present study, we investigated whether the effect of the CB1 receptor coding CNR1 gene on migraine and its symptoms is conditional on life stress. In a cross‐sectional European population (n = 2426), recruited from Manchester and Budapest, we used the ID‐Migraine questionnaire for migraine screening, the Life Threatening Experiences questionnaire to measure recent negative life events (RLE), and covered the CNR1 gene with 11 SNPs. The main genetic effects and the CNR1 × RLE interaction with age and sex as covariates were tested. None of the SNPs showed main genetic effects on possible migraine or its symptoms, but 5 SNPs showed nominally significant interaction with RLE on headache with nausea using logistic regression models. The effect of rs806366 remained significant after correction for multiple testing and replicated in the subpopulations. This effect was independent from depression‐ and anxiety‐related phenotypes. In addition, a Bayesian systems‐based analysis demonstrated that in the development of headache with nausea all SNPs were more relevant with higher a posteriori probability in those who experienced recent life stress. In summary, the CNR1 gene in interaction with life stress increased the risk of headache with nausea suggesting a specific pathological mechanism to develop migraine, and indicating that a subgroup of migraine patients, who suffer from life stress triggered migraine with frequent nausea, may benefit from therapies that increase the endocannabinoid tone.

Keywords: Bayesian relevance analysis, endocannabinoid system, gene–environment interaction, migraine, nausea, stress

Migraine is a complex multifactorial neurologic disorder, in which genetic factors explain about 46% of the risk with the remaining 54% of the variability related to environmental factors (Mulder et al. 2003). Recent genome wide association studies (GWAS) have successfully identified several genetic susceptibility loci for migraine (Anttila et al. 2013; Gormley et al. 2016) but much less is known of which genetic variants operate in the presence of a given environmental effect (Eising et al. 2013b).

One of the main environmental risk factor for migraine is psychosocial stress (Sauro & Becker 2009), and it has been demonstrated that migraine patients show maladaptive stress responses (Borsook et al. 2012; Lipton et al. 2014). The endocannabinoid system plays a key role in modulation of stress response (Hill et al. 2010; McLaughlin et al. 2014). Its two main mediators are anandamide (AEA) and 2‐arachidonoylglycerol (2‐AG) that are synthesized on demand in the postsynaptic cells and act as retrograde neurotransmitters on GABAergic and glutamatergic neurons to balance inhibitory and excitatory neural activity. In the brain the primary target of endocannabinoids is the endocannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1 receptor), which is predominantly expressed in cortical and limbic areas and is responsible for the regulation of stress response and emotional behaviour (McLaughlin et al. 2014).

Activation of the CB1 receptors enhances the activity of serotonergic (5HT) and noradrenergic (NA) neurons in the brainstem (McLaughlin et al. 2014) and, through negative feedback inhibition, controls the activity of hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis (Hill et al. 2010). Thus lack or decreased CB1 signalling results in chronic stress‐like state (Lazary et al. 2011). More importantly, it has been demonstrated that during chronic stress the endocannabinoid signalling changes gradually leading to stress habituation (Patel & Hillard 2008), which is impaired in migraine patients (Afra et al. 2000).

Indeed, it has been previously proposed that migraine is related to endocannabinoid deficiency (Russo 2004), although whether it is the cause or the consequence of migraine has not been understood yet. In human studies, the metabolism of endocannabinoids is increased in migraineurs (Cupini et al. 2006) resulting in decreased endocannabinoid tone (Sarchielli et al. 2007; Van der Schueren et al. 2012). In addition, animal studies showed that AEA was able to diminish the activation of the trigeminovascular system in nitroglycerin‐induced migraine models (Akerman et al. 2004; Greco et al. 2010; Nagy‐Grocz et al. 2015) through a CB1 receptor mediated mechanism (Akerman et al. 2013).

Indeed, our previous genetic association studies showed that genetic variants in the CB1 receptor coding CNR1 gene were associated with neuroticism (Juhasz et al. 2009a), a personality trait which predisposes to perceive life events as stressful and which is a risk factor for migraine (Ligthart & Boomsma 2012). In addition, CNR1 genetic variants in interaction with recent negative life events (RLE) increased the risk of depression (Juhasz et al. 2009a), and in interaction with the serotonin transporter functional polymorphism (5HTTLPR) exerted anxiogenic effects (Lazary et al. 2009, 2011). Regarding migraine, we demonstrated that a CNR1 haplotype increased the risk of migraine headaches (Juhasz et al. 2009b). However, recent migraine GWAS studies could not identify risk genetic variants within the endocannabinoid system (Anttila et al. 2013; Gormley et al. 2016). Although accumulating evidence suggests that impaired CB1 signalling is associated with chronic stress‐related hyperalgesia (Jennings et al. 2015; Lomazzo et al. 2015; Rea et al. 2014), the relationship between CNR1 gene and migraine has not been investigated in interaction with life stressors.

Thus, in the present study we tested the hypothesis that the CNR1 gene in interaction with life stressors is an important risk factor for migraine type headache, in a European cohort recruited from Budapest and Manchester. Furthermore, we hypothesized that the modulatory effect of life stress ‐ CNR1 gene interaction is different for specific migraine related symptoms.

Materials and methods

Subjects

Participants aged between 18 and 60 years from Greater Manchester, UK and Budapest, Hungary have been recruited through general practices and advertisements. The studies were part of NewMood (New Molecules in mood Disorders, 2004–2009), an EU funded research programme into pathomechanism of depression and related conditions. Both studies were approved by local Ethics Committees (Scientific and Research Ethics Committee of the Medical Research Council, Budapest, Hungary, ad.225/KO/2005.; ad.323‐60/2005‐1018EKU and ad.226/KO/2005.; ad.323‐61/2005‐1018 EKU; North Manchester Local Research Ethics Committee, Manchester, UK REC reference number: 05/Q1406/26) and were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent to the study. In the present research, we included participants who were European white origin, completed the questionnaires and consented to DNA. Details of the recruitment strategies and response rate were published earlier (Juhasz et al. 2009a; Lazary et al. 2009).

Questionnaires

Brief standard questionnaires, English and Hungarian versions respectively, were used for the study. The background questionnaire collected information about socio‐demographic data, personal and family psychiatric history. Sex, age, ethnicity, reported migraine and reported lifetime depression data were derived from this validated questionnaire (Juhasz et al. 2011).

The ID‐migraine questionnaire was used to collect information about headaches and especially migraine type headache symptoms in the past 3 months (Lipton et al. 2003). The ID‐Migraine is a validated screening tool for migraine, which includes 3 items of the main migraine symptoms: nausea, photophobia and disability. In the present study we assigned possible migraine to patients who answered YES to 2 or 3 migraine symptom questions as they have 93% probability of having migraine based on the IHS diagnostic criteria for migraine (Lipton et al. 2003). In addition, we investigated the genetic effect on the 3 reported symptoms separately.

The RLE score was based on the validated Life Threatening Experiences questionnaire (Brugha et al. 1985) and we calculated the sum of negative life events in the last year for the analysis.

To measure neuroticism the Big Five Inventory (BFI‐44) (John & Srivastava 1999) was applied. Current (last week) anxiety symptoms and depressive symptoms were measured by the relevant subscales of the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) (anxiety subscale for anxiety, and depression plus additive subscales for depression; (Derogatis 1993). For these variables continuous weighted dimension scores (sum of item scores divided by the number of items completed) were calculated for the analysis.

Genotyping

Genomic DNA was extracted from buccal mucosa cells (Juhasz et al. 2009a). After extraction of DNA all samples were normalized and genotyped using the Sequenom® MassARRAY Technology (Sequenom®, San Diego, CA, USA, www.sequenom.com). Genotyping was performed under the ISO 9001:2000 requirements and was blinded for the phenotypic data.

To investigate the effect of the CNR1 gene we selected possibly functional single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) from previous literature and haplotype tag SNPs (htSNPs) to cover the whole gene. Genetic data were extracted from the International HapMap project (http://hapmap.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/, Phase I. June 2005, CEPH population and AFD_EUR_18‐MAY‐2004 panel). Gabriel method implemented in the HaploView software package was used to identify htSNPs with minimum pairwise correlation r 2 = 0.8 (Gabriel et al. 2002a). The list and minor allele frequencies of the selected SNPs can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1.

Details of the investigated populations

| A. Phenotypic description | Total population | Manchester | Budapest |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Participant number (n) | 2426 | 1375 | 1051 |

| Female (n, %) | 1690 (70%) | 958 (70%) | 732 (70%) |

| Age (mean ± SEM) | 32.9 (± 0.22) | 34.04 (± 0.28) | 31.2 (± 0.34) |

| Migraine and headache | |||

| Reported migraine (n, %) | 144 (6%) | 104 (8%) | 40 (4%) |

| ID‐possible migraine (n, %) | 668 (28%) | 430 (31%) | 238 (23%) |

| ID nausea (n, %) | 710 (29%) | 454 (33%) | 256 (24%) |

| ID photophobia (n, %) | 688 (28%) | 433 (32%) | 255 (24%) |

| ID disability (n, %) | 673 (28%) | 422 (31%) | 251 (24%) |

| Stresses | |||

| Recent negative life events (mean ± SEM) | 1.22 (± 0.03) | 1.32 (± 0.04) | 1.08 (± 0.04) |

| Recent life event categories (n, %) | |||

| No or mild | 1619 (67%) | 880 (64%) | 739 (70%) |

| Moderate | 451 (19%) | 258 (19%) | 193 (19%) |

| Severe | 352 (14%) | 237 (17%) | 115 (11%) |

| Psychiatric measures | |||

| Reported lifetime depression (n, %) | 989 (41%) | 770 (56%) | 219 (21%) |

| BFI neuroticism (mean ± SEM) | 3.12 (± 0.02) | 3.36 (± 0.03) | 2.81 (± 0.03) |

| BSI current depression score (mean ± SEM) | 0.85 (± 0.02) | 1.07 (± 0.03) | 0.55 (± 0.02) |

| BSI current anxiety score (mean ± SEM) | 0.87 (± 0.02) | 1.02 (± 0.03) | 0.69 (± 0.02) |

| B. Genetic data | |||

| Minor allele frequencies (MAF) * | |||

| rs2180619 (G/A) | 39.6% | 37.8% | 42.2% |

| rs806379 (T/A) | 47.4% | 49.5% | 44.7% |

| rs1535255 (G/T) | 17.3% | 18.7% | 15.4% |

| rs2023239 (C/T) | 17.6% | 19.1% | 15.5% |

| rs806369 (T/C) | 30.0% | 27.9% | 32.8% |

| rs1049353 (A/G) | 25.9% | 28.3% | 22.7% |

| rs4707436 (A/G) | 26.1% | 28.5% | 22.9% |

| rs12720071 (G/A) | 8.8% | 8.3% | 9.6% |

| rs806368 (C/T) | 21.3% | 20.0% | 23.2% |

| rs806366 (T/C) | 48.4% | 49.7% | 46.9% |

| rs7766029 (T/C) | 48.1% | 46.3% | 50.4% |

(A) Shows the phenotypic data, (B) summarises the genetic variables.

BFI, Big Five Inventory (30); BSI, Brief Symptom Inventory (31); ID, data derived from the ID‐Migraine questionnaire (28); SEM, standard error of mean.

All SNPs are in Hardy‐Weinberg equilibrium with an average callrate of 95%.

Statistical analysis

To calculate Hardy‐Weinberg equilibrium P values, to run logistic regression analysis with additive genetic models, and to compute haplotypes PLINK v1.07 (http://pngu.mgh.harvard.edu/~purcell/plink/) analysis programme was used. First, statistical analysis for the main effect of the CNR1 SNPs and the CNR1 SNPs × RLE interactions on possible migraine and migraine‐related symptoms were carried out in the total sample, according to a recent guideline (Dick et al. 2015). Pairwise deletion was used to handle missing data. To adjust P values for the multiple testing false discovery rate q values were calculated and were accepted at level of 5% (Q value, http://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/qvalue.html). To handle possible ancestral differences, ethnicity was determined by the self‐reported data derived from the Background questionnaire (see Questionnaires) and subjects with European white origin were included in the analysis. In addition, possible ancestral differences according to study sites were tested by including this factor (namely, Budapest vs. Manchester) into the post hoc tests. Thus we tested the main finding in these subgroups separately, and also ran a post hoc test by including study site into the analysis.

In addition, haplotypes were computed for the nominally significant SNPs in haploblock 1 applying the expectation maximization (EM) algorithm. The effects of the computed haplotypes were similarly tested in the total sample as the SNPs, also as a post hoc test. Age and sex were covariates in all analyses.

To further explore the effects of CNR1 SNPs in subpopulations defined by the recent life event categories (no or mild = 0–1, moderate = 2, severe = 3 or more) systems‐based Bayesian relevance analysis was carried out (Antal et al. 2006, 2014; Hullam et al. 2012) to determine the strong relevance of predictors (11 CNR1 SNPs, age and sex) with respect to headache with nausea. This method applies Bayesian model averaging, both at structural and parametric levels, which provides a coherent multivariate solution for the multiple hypothesis problem. For detailed method, see Antal et al. (2014) and Juhasz et al. (2014, 2015).

Additional statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 21.0 for Windows (IBM). All statistical testing adopted two‐tailed P = 0.05 threshold. For display purposes, in all three RLE severity categories, we calculated positive likelihood ratios (LR+) for significant genotypes and haplotypes by dividing the genotype/haplotype frequencies in possible migraine cases/symptom carriers by those in control subjects/non‐carriers, as previously described (Juhasz et al. 2009b).

Quanto 1.2 version (http://biostats.usc.edu/Quanto.html/) was employed to calculate the power of the recruited populations. Assuming a case–control design (3 controls/case) and an additive genetic model with a minor allele frequency between 10% and 50% in our study (n = 2426) we have 45–84% power to detect genetic main effects and 65–95% power to detect a gene × environment interaction (P = 0.05 two‐tailed) that is associated with 1.2 odds ratio for a disease.

Results

Detailed description of the included study population can be found in Table 1. Two‐thirds of the recruited study population was female and about 40% reported lifetime depression.

Despite the fact that only 6% of the subjects reported migraine as a long‐standing medical condition in the total study population, about one‐third of the subjects had migraine‐related symptoms when they experienced headache in the last 3 months. Based on our data in this study the ID migraine questionnaire compared to the reported migraine had 85% sensitivity and 76% specificity to identify possible migraine, which is in a comparable range with the original validation study (Lipton et al. 2003).

CNR1 gene

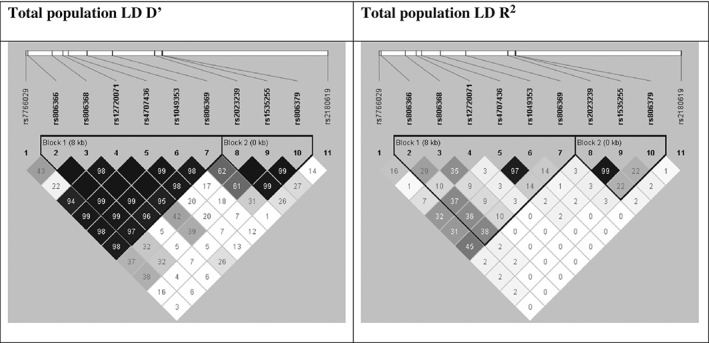

All of the investigated SNPs were in Hardy‐Weinberg equilibrium, both in the total population and in the separate populations according to study sites of Budapest and Manchester, respectively. Linkage analysis in HaploView (Barrett et al. 2005; Gabriel et al. 2002b) showed two main haploblocks (haploblock 1: rs806366, rs806368, rs12720071, rs4707436, rs1049353, rs806369, and haploblock 2: rs2023239, rs1535255, rs806379; while rs7766029 at the 3′ end and rs2180619 at the 5′ end were not in linkage with these haploblocks. This genetic structure was similar in the Budapest and Manchester sample and agrees with the LD pattern of the European white populations. (For LD block structure of the total population see Fig. 1, and of the investigated subpopulations see Fig. S1.)

Figure 1.

LD block structure of the total population. Linkage analysis showed two main haploblocks (haploblock 1: rs806366, rs806368, rs12720071, rs4707436, rs1049353, rs806369 and haploblock 2: rs2023239, rs1535255, rs806379; while rs7766029 at the 3′ end and rs2180619 at the 5′ end were not in linkage with these haploblocks.

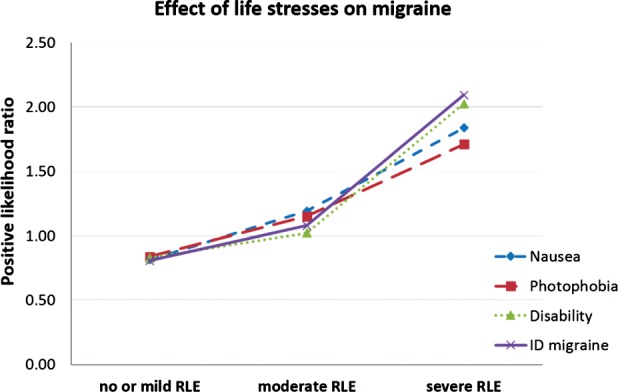

Main effect of RLEs on headache

Using logistic regression model, as we expected, with increasing number of RLE the odds of having possible migraine or migraine related symptoms were increased [possible migraine: Odds Ratio (OR) = 1.32 (95% CI 1.23–1.41) P < 0.001; nausea: OR = 1.24 (95% CI 1.16–1.33) P < 0.001; photophobia: OR = 1.24 (95% CI 1.16–1.33) P < 0.001; disability: OR = 1.28 (95% CI 1.19–1.37) P < 0.001; Fig. 2]. This effect remained significant when lifetime depression, current depression and anxiety score, and neuroticism were included in the regression model [possible migraine: OR = 1.17 (95% CI 1.08–1.26) P < 0.001; nausea: OR = 1.10 (95% CI 1.02–1.18) P = 0.014; photophobia: OR = 1.15 (95% CI 1.07–1.23) P < 0.001; disability: OR = 1.16 (95% CI 1.08–1.25) P < 0.001].

Figure 2.

Effect of life stresses on headache. RLEs (recent negative life events) experienced in the last year increased the positive likelihood ratio of having possible migraine or migraine related symptoms with headache, defined by the ID‐Migraine screening questionnaire.

Main effect of CNR1 gene on headache

None of the investigated SNPs showed significant main genetic effect on possible migraine or migraine related symptoms using logistic regression models with age and sex as co‐variants.

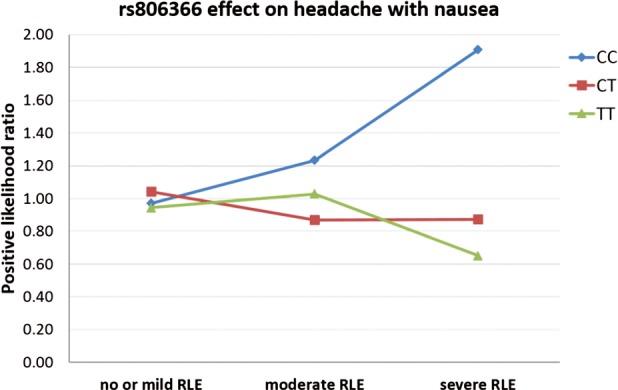

CNR1 × RLE interaction on headache

Nominally significant interaction effects were identified between rs1049353, rs806366, rs7766029 and RLE on possible migraine, between rs806369, rs1049353, rs4707436, rs806366, rs7766029 and RLE on headache with nausea, and between rs806366 and RLE on headache with disability (Table 2). Taking into account the number of tests we carried out (4 phenotypes, genetic main effect, gene × environment interactions, 11 SNPs) after false discovery rate correction for multiple testing the interaction effect of rs806366 and RLE on headache with nausea remained significant (FDR q = 0.040). The minor T allele decreased the risk of having headache with nausea with the increasing number of RLE (Fig. 3).

Table 2.

Statistical results of interaction effect between RLE and CNR1 gene haplotype tag SNPs in the total study population

| SNP | A1 | Possible migraine | Headache with nausea | Headache with photophobia | Headache with disability | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | L95 | U95 | P | OR | L95 | U95 | P | OR | L95 | U95 | P | OR | L95 | U95 | P | |||

| 1 | rs2180619 | G | 1.006 | 0.908 | 1.115 | 0.904 | 0.922 | 0.834 | 1.021 | 0.118 | 1.000 | 0.904 | 1.106 | 0.999 | 1.021 | 0.923 | 1.130 | 0.687 |

| 2 | rs806379 | T | 0.969 | 0.877 | 1.071 | 0.537 | 1.012 | 0.917 | 1.117 | 0.811 | 0.910 | 0.825 | 1.004 | 0.061 | 1.007 | 0.912 | 1.112 | 0.893 |

| 3 | rs1535255 | G | 0.919 | 0.808 | 1.044 | 0.195 | 0.939 | 0.828 | 1.065 | 0.326 | 0.963 | 0.850 | 1.093 | 0.562 | 0.966 | 0.851 | 1.097 | 0.594 |

| 4 | rs2023239 | C | 0.931 | 0.816 | 1.062 | 0.287 | 0.935 | 0.822 | 1.063 | 0.302 | 0.985 | 0.867 | 1.120 | 0.820 | 1.000 | 0.878 | 1.138 | 0.994 |

| 5 | rs806369 | T | 1.085 | 0.967 | 1.217 | 0.166 | 1.123 | 1.002 | 1.259 | 0.045 | 1.090 | 0.974 | 1.221 | 0.134 | 1.086 | 0.970 | 1.217 | 0.154 |

| 6 | rs1049353 | A | 0.885 | 0.789 | 0.993 | 0.037 | 0.846 | 0.755 | 0.948 | 0.004 | 0.965 | 0.863 | 1.079 | 0.531 | 0.915 | 0.817 | 1.024 | 0.123 |

| 7 | rs4707436 | A | 0.892 | 0.796 | 1.001 | 0.051 | 0.860 | 0.767 | 0.963 | 0.009 | 0.981 | 0.877 | 1.097 | 0.737 | 0.928 | 0.829 | 1.039 | 0.196 |

| 8 | rs12720071 | G | 1.003 | 0.833 | 1.209 | 0.974 | 0.980 | 0.816 | 1.178 | 0.832 | 0.944 | 0.786 | 1.132 | 0.531 | 0.933 | 0.780 | 1.115 | 0.447 |

| 9 | rs806368 | C | 1.010 | 0.896 | 1.139 | 0.873 | 0.943 | 0.838 | 1.061 | 0.327 | 0.985 | 0.876 | 1.107 | 0.797 | 0.974 | 0.865 | 1.096 | 0.661 |

| 10 | rs806366 | T | 0.884 | 0.791 | 0.987 | 0.028 | 0.819 | 0.733 | 0.916 | 0.0005 * | 0.959 | 0.862 | 1.066 | 0.438 | 0.896 | 0.804 | 0.999 | 0.048 |

| 11 | rs7766029 | T | 1.111 | 1.001 | 1.232 | 0.047 | 1.114 | 1.006 | 1.234 | 0.038 | 1.079 | 0.976 | 1.194 | 0.139 | 1.103 | 0.996 | 1.222 | 0.060 |

Possible migraine: 2 or 3 migraine related symptoms measured by the ID‐Migraine screening questionnaire.

Bold, nominally significant effects; italic, trend effects; L95‐U95, 95% confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; P, significance.

Remained significant after false discovery rate correction of multiple testing.

Figure 3.

rs806366 effect on headache with nausea. The interaction effect of recent negative life events (RLE) and the rs806366 within the CNR1 gene on headache with nausea in the total population. Number of cases in the no or mild RLE group: CC = 361, CT = 684, TT = 315. Number of cases in the moderate RLE group: CC = 103, CT = 183, TT = 95. Number of cases in the severe RLE groups: CC = 74, CT = 147, TT = 69.

Post hoc tests of CNR1 × RLE interaction on headache with nausea

Investigating the CNR1 × RLE interaction on headache with nausea separately according to study sites, 8 out of 11 SNPs showed the same direction of effect in both populations and the effect of rs806366 × RLE was replicated in the Budapest and Manchester samples at nominal significance level (Table 3).

Table 3.

Post hoc analysis of CNR1 × RLE interaction on headache with nausea in the separate study populations, and in the total population after controlling for study sites, neuroticism, lifetime depression and current depression and anxiety scores

| SNP | A1 | Budapest | Manchester | Total population corrected for study site and depression related variables | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | L95 | U95 | P | OR | L95 | U95 | P | OR | L95 | U95 | P | |||

| 1 | rs2180619 | G | 1.055 | 0.879 | 1.266 | 0.564 | 0.870 | 0.768 | 0.985 | 0.028 | 0.931 | 0.836 | 1.036 | 0.189 |

| 2 | rs806379 | T | 0.905 | 0.759 | 1.080 | 0.268 | 1.083 | 0.959 | 1.224 | 0.199 | 1.033 | 0.930 | 1.146 | 0.547 |

| 3 | rs1535255 | G | 0.977 | 0.791 | 1.208 | 0.830 | 0.923 | 0.788 | 1.081 | 0.322 | 0.935 | 0.820 | 1.067 | 0.319 |

| 4 | rs2023239 | C | 0.937 | 0.757 | 1.160 | 0.550 | 0.939 | 0.798 | 1.105 | 0.449 | 0.925 | 0.809 | 1.057 | 0.253 |

| 5 | rs806369 | T | 1.173 | 0.962 | 1.430 | 0.115 | 1.087 | 0.942 | 1.254 | 0.252 | 1.128 | 0.998 | 1.275 | 0.054 |

| 6 | rs1049353 | A | 0.875 | 0.711 | 1.077 | 0.209 | 0.834 | 0.726 | 0.959 | 0.011 | 0.840 | 0.744 | 0.948 | 0.005 |

| 7 | rs4707436 | A | 0.869 | 0.706 | 1.068 | 0.181 | 0.856 | 0.745 | 0.983 | 0.028 | 0.854 | 0.757 | 0.964 | 0.010 |

| 8 | rs12720071 | G | 1.176 | 0.853 | 1.621 | 0.324 | 0.910 | 0.721 | 1.150 | 0.431 | 0.964 | 0.797 | 1.164 | 0.700 |

| 9 | rs806368 | C | 0.953 | 0.783 | 1.160 | 0.630 | 0.943 | 0.811 | 1.095 | 0.440 | 0.941 | 0.831 | 1.065 | 0.335 |

| 10 | rs806366 | T | 0.818 | 0.677 | 0.988 | 0.037 | 0.829 | 0.720 | 0.955 | 0.009 | 0.814 | 0.722 | 0.917 | 0.0007 |

| 11 | rs7766029 | T | 1.026 | 0.848 | 1.240 | 0.792 | 1.149 | 1.013 | 1.303 | 0.030 | 1.104 | 0.990 | 1.232 | 0.076 |

Bold, nominally significant effects; italic, trend effects; L95‐U95, 95% confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; P, significance.

In the total population, the rs806366 × RLE interaction effect remained significant after controlling for the effects of the study site, neuroticism, lifetime depression and current depression and anxiety scores (Table 3).

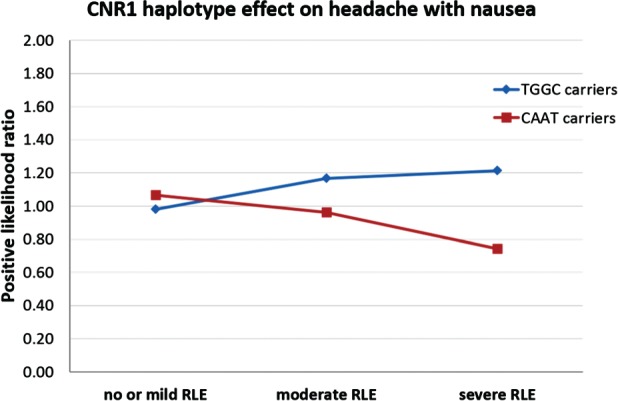

To demonstrate the cumulative effect of the significant SNPs in haploblock 1 (rs806366, rs4707436, rs1049353, rs806369) in the total population we computed haplotypes and tested the CNR1 × RLE interaction effects on headache with nausea (for haplotype frequency and results see Table S1, Supporting Information and Fig. 2). The most frequent TGGC haplotype (frequency 30.8%) was a significant risk variant [OR = 1.20 (95% CI 1.06–1.36) P = 0.005] whereas the complementary CAAT haplotype (frequency 26.5%) showed significant protective effect [OR = 0.84 (95% CI 0.75–0.95) P = 0.006; Fig. 4]. Other frequent haplotypes (frequency > 5%) had no significant interaction effect on headache with nausea.

Figure 4.

CNR1 haplotype effect on headache with nausea. Significant CNR1 haplotype × recent negative life events (RLE) interaction effects on headache with nausea in the total population. Number of cases in the no or mild RLE group: TGGC carriers = 733, CAAT carriers = 620. Number of cases in the moderate RLE group: TGGC carriers = 186, CAAT carriers = 177. Number of cases in the severe RLE groups: TGGC carriers = 152, CAAT carriers = 144.

Bayesian relevance of CNR1 SNPs on headache with nausea in different RLE categories

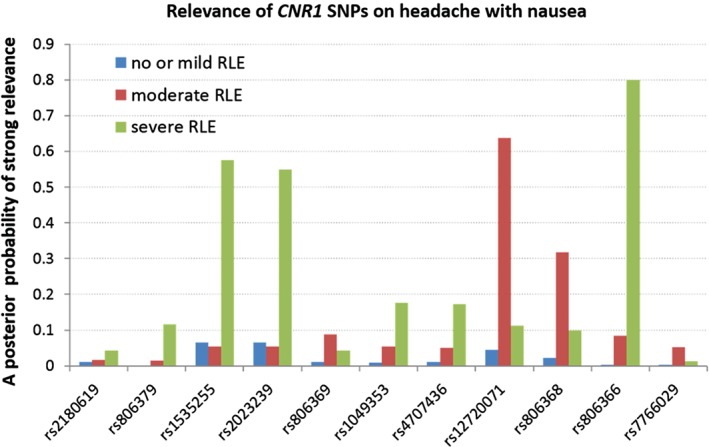

Using a Bayesian model averaging approach over models consisting of all SNPs plus age and sex, an a posteriori probability of strong relevance was calculated for each predictor. Results indicated that all CNR1 SNPs had higher a posteriori probability of strong relevance in subgroups with either moderate or severe RLE (moderate = 2, severe = 3 or more serious life events in the last year) compared to no or mild RLE (no or mild = 0–1 serious life events in the last year) (Fig. 5 and Appendix S1). The a posteriori probability of strong relevance was highest for rs806366 (Pr = 0.8) in the severe RLE subpopulation, giving a similar result to the frequentist analysis. This suggests that in 80% of all models the rs806366 was an important factor to determine headache with nausea.

Figure 5.

Relevance of CNR1 SNPs on headache with nausea. A posteriori probability of strong relevance of CNR1 SNPs on headache with nausea according to the RLE (recent negative life events) exposure.

Discussion

Our results show that the CNR1 gene in interaction with life stresses increases the risk of headache with nausea, suggesting a potential specific pathological mechanism in the development of migraine. This finding emphasises that possible migraine, as a screening questionnaire outcome, is not directly associated with the CNR1 gene, which is supported by recent GWAS studies (Anttila et al. 2013). However, (1) the CNR1 gene exerts a significant effect on headache with nausea rather than possible migraine itself, and (2) the CNR1 gene effect on headache with nausea is conditional on the presence of stressors that might serve as migraine triggers. This latter observation is supported by previous studies, which confirmed that endocannabinoid signalling has a fundamental role in stress adaptation (Hill et al. 2010).

A recent large meta‐analysis of GWAS studies (Anttila et al. 2013) identified several susceptible genetic loci for migraine from which only one (TRPM8, encoding the transient receptor potential melastatin 8, which is a cold and menthol‐activated ion channel in sensory neurons) has a direct role in pain sensation. The other genetic variants are predominantly expressed in the brain, mainly exert their effects through synaptic and neuronal regulation (Anttila et al. 2013; Eising et al. 2013a) and thus may contribute to the neuronal hyperexcitability of the migraine brain. In addition, it has been demonstrated that these genetic variants, with the exception of TRPM8, show different and unique association patterns with additional migraine features, such as nausea, photophobia or aggravation by physical activity, which suggests that genetic variants play a divergent pathophysiological role in the development of migraine (Chasman et al. 2014; Zameel Cader 2013), similar to our finding.

The endocannabinoid system, acting through the CNR1 coded CB1 receptor, is another key player in synaptic plasticity that has modulatory effects on trigeminovascular activation (Akerman et al. 2004, 2013; Nagy‐Grocz et al. 2015), pain processing (Morena et al. 2016) and regulation of nausea and vomiting (Parker et al. 2011; Sharkey et al. 2014) drawing attention to its potential role in the pathophysiology of migraine.

Our results do not support the hypothesis that in humans genetic variations of the CNR1 gene are directly associated with migraine type headache through the effect of endocannabinoid system on trigeminovascular activation. This is because we have not seen any significant main effects of SNPs on possible migraine headache. Indeed, CB1 receptors are more abundantly expressed in the prefrontal cortical areas compared to the brainstem (McLaughlin et al. 2014). In our previous smaller study, we found direct effects of CNR1 gene on migraine only when using extreme trait combinations (0 symptoms vs. 3 symptoms on ID‐Migraine questionnaire) and haplotype analysis of the CNR1 gene. Even in this case, in the extended sample (including those who has only 1 or 2 symptoms) the distribution of association patterns with other migraine related symptoms were uneven (Juhasz et al. 2009b) suggesting that this gene has a selective pathophysiological role.

The endocannabinoid system plays an important regulatory role in pain processing at multiple levels of this pathway. The activation of the CB1 receptors have analgesic effects at the peripheral sensory afferents, in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, the periaqueductal grey (PAG) and the brainstem (Woodhams et al. 2015). In addition, endocannabinoids are indispensable in the development of acute stress induced analgesia (Morena et al. 2016), and the downregulation of endocannabinoid signalling is an important mechanism in the development of chronic stress induced hyperalgesia (Jennings et al. 2015; Lomazzo et al. 2015; Rea et al. 2014). However, more and more evidence suggests that endocannabinoids mainly influence the affective component of pain, in which amygdala activity has a pivotal role, compared to the sensory aspects (Lee et al. 2013). As such, the strength of life stress × CNR1 gene interaction on headache with nausea would be expected to decrease after controlling for depression and anxiety related phenotypes, but this was not the case. Thus, our findings suggest that a distinctive mechanism related to stress induced headache with nausea is primarily responsible for the effect of CNR1 gene in migraine type headache in humans.

Nausea and/or vomiting is a characteristic feature of migraine headache, which has been reported by 70–90% of migraine patients (Lipton et al. 2001). The presence of nausea and its intensity correlates significantly with migraine pain severity (Kelman & Tanis 2006). In addition, frequent nausea occurs in about 50% of migraine sufferers where headache is accompanied by nausea more than half of the time, which predicts more disability (Lipton et al. 2013), worse quality of life, and transition to chronic migraine (Reed et al. 2015). Furthermore, a major problem with nausea is that it can interfere with willingness to take and ingest oral migraine medication causing ineffective pain control (Lipton et al. 2013).

Accumulating evidence supports cannabis and endocannabinoids supressing emesis and nausea through the CB1 receptor (Parker et al. 2011; Sharkey et al. 2014). In animal models, cannabinoid derivatives have a distinctive effect compared to other available antiemetic drugs in being able to suppress not only vomiting but also anticipatory and delayed nausea, probably via the inhibitory effect of CB1 receptors on serotonin release in the insular cortex (Parker et al. 2015); this is a possible mechanism in humans as well.

The neural regulator of emesis is integrated at the dorsal vagal complex, which receives peripheral (gut), vestibular, and cerebral inputs and initiates motor response characteristic for vomiting (Parker et al. 2011; Sharkey et al. 2014). Nevertheless, the neuronal control of nausea is poorly understood but is clearly distinctive from the emesis control. A recent human functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) study suggested that sustained nausea activates an extensive network of limbic, interoceptive and cognitive brain areas including the insular cortex and the anterior cingulate (Napadow et al. 2013). Correlation between the activity of the insular cortex and midcingulate predicted the development of strong nausea (Napadow et al. 2013). In addition, a recent PET study demonstrated that nausea as a premonitory symptom during nitroglycerin‐induced migraine is centrally driven by activation of the PAG and rostral dorsal medulla or regions that control their activity (Maniyar et al. 2014).

The headache escalating effect of nausea can be experimentally demonstrated in migraine patients during motion sickness by applying a painful stimuli on the face (Drummond & Granston 2004). This observation suggests that the dorsovagal complex and the trigeminovascular complex mutually relay information to each other which leads to a vicious circle increasing both symptoms (Cuomo‐Granston & Drummond 2010; Drummond & Granston 2004). It is interesting to note, that migraineurs are more susceptible to motion sickness than controls probably due to the ineffective top‐down control on relevant brainstem areas in response to excessive or stressful sensory inputs (Cuomo‐Granston & Drummond 2010). Regarding motion sickness, it has been demonstrated that those who respond with acute motion sickness to parabola flight have significantly higher stress scores accompanied by increased salivary cortisol concentration, lower whole blood endocannabinoid levels and decreased CB1 mRNA leukocyte expression compared to those with no motion sickness (Chouker et al. 2010).

Limitations

The main advantage of our study is that the systematic investigation of genetic main effect and stress interaction on different migraine related symptoms allowed us to delineate a specific pathomechanism, which may contribute to the development of migraine in a susceptible subgroup of patients. However, the study has some limitations. Although we managed to replicate our findings in two European populations, independent replications will be necessary to confirm our results. Our study had a cross‐sectional design, therefore the causative role of life stressors and the temporal relationship between stress and headache could not be investigated. Furthermore, we used a short screening questionnaire to determine the probability of migraine headache and to identify migraine related symptoms without proper medical diagnosis. Nevertheless, this is a usual method in large population based studies and previous epidemiologic and GWAS studies suggest that this method provides trustworthy results (Anttila et al. 2013).

Finally, although we covered the whole CNR1 gene with haplotype tag SNPs to determine its function in migraine, the endocannabinoid system is a very complex network of synthetizing and metabolizing enzymes, receptors and transporters with high potential to adaptive changes. For example, genetic variants in the gene of fatty acid amide hydrolase (FAAH) enzyme, which metabolizes AEA, have been associated not only with pain sensitivity (Cajanus et al. 2016) but with mood symptoms elicited by early life stress (Lazary et al. 2016), probably through neurodevelopmental effects. Indeed, the endocannabinoid system is responsible to regulate divergent physiological processes from metabolic routes through regulation of emotional behaviour to pain modulation, reflected by its broad expression throughout the brain and other parts of the body, making it challenging to specifically target it by therapeutic interventions. Although, a promising approach is to increase the endocannabinoid tone by inhibiting the FAAH enzyme that showed antinociceptive (Greco et al. 2015) and antiemetic (Parker et al. 2015) effects in animal models, serious treatment related adverse events in a recent human study suggest that tissue and/or receptor specific cannabinoids are warranted (Kaur et al. 2016).

Conclusions

In conclusion, our results suggest that genetic variations in the CNR1 gene increases the risk of developing headache with nausea in life stress exposed subjects most likely through an impaired endocannabinoid system driven top‐down cortical control on important brainstem areas. Based on these results a subgroup of migraine patients, who have frequent nausea associated with migraine attacks triggered by moderate or severe life stress, may benefit from therapies that increase the endocannabinoid tone.

Supporting information

Appendix S1: Advantage of the Bayesian system‐based analysis and potential biological explanation of the results.

Table S1: Haplotype frequencies in the CNR1 gene (using the nominally significant SNPs in haploblock 1: rs806366, rs4707436, rs1049353, rs806369), and statistical results of interaction effects between recent negative life events (RLE) and haplotypes on headache with nausea in the total study population.

Figure S1: LD block structure of the investigated subpopulations.

Figure S2: LD block structure of rs806366, rs4707436, rs1049353, rs806369 in the total population.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by the MTA‐SE‐NAP B Genetic Brain Imaging Migraine Research Group, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Semmelweis University (Grant No. KTIA_NAP_13‐2‐2015‐0001); the Sixth Framework Program of the European Union, NewMood (Grant No. LSHM‐CT‐2004‐503474); by the National Development Agency (Grant No. KTIA_NAP_13‐1‐2013‐0001), Hungarian Brain Research Program – Grant No. KTIA_13_NAP‐A‐II/14; by the National Institute for Health Research Manchester Biomedical Research Centre; and the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (MTA‐SE Neuropsychopharmacology and Neurochemistry Research Group). The sponsors had no further role in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication. We thank Diana Chase, Emma J. Thomas, Darragh Downey, Dorottya Pap, Judit Lazary, Zoltan G. Toth for their assistance in the recruitment and data acquisition and Hazel Platt for her assistance in genotyping. J.F.W.D. variously performed consultancy, speaking engagements and research for Bristol‐Myers Squibb, AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Schering Plough, Janssen‐Cilag and Servier (all fees are paid to the University of Manchester to reimburse them for the time taken); he has share options in P1vital. I.M.A. has received consultancy fees from Servier, Alkermes, Lundbeck/Otsuka and Janssen, an honorarium for speaking from Lundbeck and grant support from Servier and AstraZeneca. All other authors report no financial relationships with commercial interests.

References

- Afra, J. , Proietti Cecchini, A. , Sandor, P.S. & Schoenen, J. (2000) Comparison of visual and auditory evoked cortical potentials in migraine patients between attacks. Clin Neurophysiol 111, 1124–1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akerman, S. , Kaube, H. & Goadsby, P.J. (2004) Anandamide is able to inhibit trigeminal neurons using an in vivo model of trigeminovascular‐mediated nociception. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 309, 56–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akerman, S. , Holland, P.R. , Lasalandra, M.P. & Goadsby, P.J. (2013) Endocannabinoids in the brainstem modulate dural trigeminovascular nociceptive traffic via CB1 and “triptan” receptors: implications in migraine. J Neurosci 33, 14869–14877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antal, P. , Gezsi, A. , Hullam, G. & Millinghoffer, A. (2006) Learning complex Bayesian network features for classification In Studeny M. & Vomlel J. (eds), Proceedings of the third European Workshop on Probabilistic Graphical Models. Action M Agency, Prague, Czech Republic, pp. 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Antal, P. , Millinghoffer, A. , Hullám, G. , Hajós, G. , Sárközy, P. , Gezsi, A. , Szalai, C. & Falus, A. (2014) Bayesian, systems‐based, multilevel analysis of associations for complex phenotypes: from interpretation to decision In Sinoquet C. & Mourad R. (eds), Probabilistic Graphical Models for Genetics, Genomics, and Postgenomics. Oxford University Press, New York, pp. 319–360. [Google Scholar]

- Anttila, V. , Winsvold, B.S. , Gormley, P. et al. (2013) Genome‐wide meta‐analysis identifies new susceptibility loci for migraine. Nat Genet 45, 912–917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, J.C. , Fry, B. , Maller, J. & Daly, M.J. (2005) Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics 21, 263–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsook, D. , Maleki, N. , Becerra, L. & McEwen, B. (2012) Understanding migraine through the lens of maladaptive stress responses: a model disease of allostatic load. Neuron 73, 219–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brugha, T. , Bebbington, P. , Tennant, C. & Hurry, J. (1985) The list of threatening experiences: a subset of 12 life event categories with considerable long‐term contextual threat. Psychol Med 15, 189–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cajanus, K. , Holmstrom, E.J. , Wessman, M. , Anttila, V. , Kaunisto, M.A. & Kalso, E. (2016) Effect of endocannabinoid degradation on pain: role of FAAH polymorphisms in experimental and postoperative pain in women treated for breast cancer. Pain 157, 361–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chasman, D.I. , Anttila, V. , Buring, J.E. , Ridker, P.M. , Schurks, M. , Kurth, T. & International Headache Genetics, C (2014) Selectivity in genetic association with sub‐classified migraine in women. PLoS Genet 10, e1004366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chouker, A. , Kaufmann, I. , Kreth, S. , Hauer, D. , Feuerecker, M. , Thieme, D. , Vogeser, M. , Thiel, M. & Schelling, G. (2010) Motion sickness, stress and the endocannabinoid system. PLoS One 5, e10752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuomo‐Granston, A. & Drummond, P.D. (2010) Migraine and motion sickness: what is the link? Prog Neurobiol 91, 300–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cupini, L.M. , Bari, M. , Battista, N. , Argiro, G. , Finazzi‐Agro, A. , Calabresi, P. & Maccarrone, M. (2006) Biochemical changes in endocannabinoid system are expressed in platelets of female but not male migraineurs. Cephalalgia 26, 277–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis, L.R. (1993) BSI: Brief Symptom Inventory: Administration, Scoring, and Procedures Manual. National Computer Systems Pearson Inc., Minneapolis, MN. [Google Scholar]

- Dick, D.M. , Agrawal, A. , Keller, M.C. , Adkins, A. , Aliev, F. , Monroe, S. , Hewitt, J.K. , Kendler, K.S. & Sher, K.J. (2015) Candidate gene‐environment interaction research: reflections and recommendations. Perspect Psychol Sci 10, 37–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond, P.D. & Granston, A. (2004) Facial pain increases nausea and headache during motion sickness in migraine sufferers. Brain 127, 526–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eising, E. , de Vries, B. , Ferrari, M.D. , Terwindt, G.M. & van den Maagdenberg, A.M. (2013a) Pearls and pitfalls in genetic studies of migraine. Cephalalgia 33, 614–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eising, E.N.A.D. , van den Maagdenberg, A.M. & Ferrari, M.D. (2013b) Epigenetic mechanisms in migraine: a promising avenue? BMC Med 11, 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel, S.B. , Schaffner, S.F. , Nguyen, H. , Moore, J.M. , Roy, J. , Blumenstiel, B. , Higgins, J. , DeFelice, M. , Lochner, A. , Faggart, M. , Liu‐Cordero, S.N. , Rotimi, C. , Adeyemo, A. , Cooper, R. , Ward, R. , Lander, E.S. , Daly, M.J. & Altshuler, D. (2002a) The structure of haplotype blocks in the human genome. Science 296, 2225–2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel, S.B. , Schaffner, S.F. , Nguyen, H. , Moore, J.M. , Roy, J. , Blumenstiel, B. , Higgins, J. , Defelice, M. , Lochner, A. , Faggart, M. , Liu‐Cordero, S.N. , Rotimi, C. , Adeyemo, A. , Cooper, R. , Ward, R. , Lander, E.S. , Daly, M.J. & Altshuler, D. (2002b) The structure of haplotype blocks in the human genome. Science 296, 2225–2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gormley, P. , Anttila, V. , Winsvold, B.S. et al. (2016) Meta‐analysis of 375,000 individuals identifies 38 susceptibility loci for migraine. Nat Genet 48, 856–866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greco, R. , Gasperi, V. , Maccarrone, M. & Tassorelli, C. (2010) The endocannabinoid system and migraine. Exp Neurol 224, 85–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greco, R. , Bandiera, T. , Mangione, A. , Demartini, C. , Siani, F. , Nappi, G. , Sandrini, G. , Guijarro, A. , Armirotti, A. , Piomelli, D. & Tassorelli, C. (2015) Effects of peripheral FAAH blockade on NTG‐induced hyperalgesia‐evaluation of URB937 in an animal model of migraine. Cephalalgia 35, 1065–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill, M.N. , McLaughlin, R.J. , Bingham, B. , Shrestha, L. , Lee, T.T. , Gray, J.M. , Hillard, C.J. , Gorzalka, B.B. & Viau, V. (2010) Endogenous cannabinoid signaling is essential for stress adaptation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107, 9406–9411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hullam, G. , Juhasz, G. , Bagdy, G. & Antal, P. (2012) Beyond structural equation modeling: model properties and effect size from a Bayesian viewpoint. An example of complex phenotype‐genotype associations in depression. Neuropsychopharmacol Hung 14, 273–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennings, E.M. , Okine, B.N. , Olango, W.M. , Roche, M. & Finn, D.P. (2015) Repeated forced swim stress differentially affects formalin‐evoked nociceptive behaviour and the endocannabinoid system in stress normo‐responsive and stress hyper‐responsive rat strains. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 64, 181–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John, O.P. & Srivastava, S. (1999) The Big Five trait taxonomy: history, measurement, and theoretical perspectives In Pervin L.A. & John O.P. (eds), Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research. Guilford Press, New York, pp. 102–139. [Google Scholar]

- Juhasz, G. , Chase, D. , Pegg, E. , Downey, D. , Toth, Z.G. , Stones, K. , Platt, H. , Mekli, K. , Payton, A. , Elliott, R. , Anderson, I.M. & Deakin, J.F. (2009a) CNR1 gene is associated with high neuroticism and low agreeableness and interacts with recent negative life events to predict current depressive symptoms. Neuropsychopharmacology 34, 2019–2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juhasz, G. , Lazary, J. , Chase, D. , Pegg, E. , Downey, D. , Toth, Z.G. , Stones, K. , Platt, H. , Mekli, K. , Payton, A. , Anderson, I.M. , Deakin, J.F. & Bagdy, G. (2009b) Variations in the cannabinoid receptor 1 gene predispose to migraine. Neurosci Lett 461, 116–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juhasz, G. , Dunham, J.S. , McKie, S. , Thomas, E. , Downey, D. , Chase, D. , Lloyd‐Williams, K. , Toth, Z.G. , Platt, H. , Mekli, K. , Payton, A. , Elliott, R. , Williams, S.R. , Anderson, I.M. & Deakin, J.F. (2011) The CREB1‐BDNF‐NTRK2 pathway in depression: multiple gene‐cognition‐environment interactions. Biol Psychiatry 69, 762–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juhasz, G. , Hullam, G. , Eszlari, N. , Gonda, X. , Antal, P. , Anderson, I.M. , Hokfelt, T.G. , Deakin, J.F. & Bagdy, G. (2014) Brain galanin system genes interact with life stresses in depression‐related phenotypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111, E1666–1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juhasz, G. , Gonda, X. , Hullam, G. , Eszlari, N. , Kovacs, D. , Lazary, J. , Pap, D. , Petschner, P. , Elliott, R. , Deakin, J.F. , Anderson, I.M. , Antal, P. , Lesch, K.P. & Bagdy, G. (2015) Variability in the effect of 5‐HTTLPR on depression in a large European population: the role of age, symptom profile, type and intensity of life stressors. PLoS One 10, e0116316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, R. , Ambwani, S.R. & Singh, S. (2016) Endocannabinoid system: a multi‐facet therapeutic target. Curr Clin Pharmacol 11, 110–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelman, L. & Tanis, D. (2006) The relationship between migraine pain and other associated symptoms. Cephalalgia 26, 548–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazary, J. , Lazary, A. , Gonda, X. , Benko, A. , Molnar, E. , Hunyady, L. , Juhasz, G. & Bagdy, G. (2009) Promoter variants of the cannabinoid receptor 1 gene (CNR1) in interaction with 5‐HTTLPR affect the anxious phenotype. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 150B, 1118–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazary, J. , Juhasz, G. , Hunyady, L. & Bagdy, G. (2011) Personalized medicine can pave the way for the safe use of CB(1) receptor antagonists. Trends Pharmacol Sci 32, 270–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazary, J. , Eszlari, N. , Juhasz, G. & Bagdy, G. (2016) Genetically reduced FAAH activity may be a risk for the development of anxiety and depression in persons with repetitive childhood trauma. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 26, 1020–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.C. , Ploner, M. , Wiech, K. , Bingel, U. , Wanigasekera, V. , Brooks, J. , Menon, D.K. & Tracey, I. (2013) Amygdala activity contributes to the dissociative effect of cannabis on pain perception. Pain 154, 124–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ligthart, L. & Boomsma, D.I. (2012) Causes of comorbidity: pleiotropy or causality? Shared genetic and environmental influences on migraine and neuroticism. Twin Res Hum Genet 15, 158–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipton, R.B. , Stewart, W.F. , Diamond, S. , Diamond, M.L. & Reed, M. (2001) Prevalence and burden of migraine in the United States: data from the American Migraine Study II. Headache 41, 646–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipton, R.B. , Dodick, D. , Sadovsky, R. , Kolodner, K. , Endicott, J. , Hettiarachchi, J. , Harrison, W. & study, I.D.M.v (2003) A self‐administered screener for migraine in primary care: the ID Migraine validation study. Neurology 61, 375–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipton, R.B. , Buse, D.C. , Saiers, J. , Fanning, K.M. , Serrano, D. & Reed, M.L. (2013) Frequency and burden of headache‐related nausea: results from the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) study. Headache 53, 93–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipton, R.B. , Buse, D.C. , Hall, C.B. , Tennen, H. , Defreitas, T.A. , Borkowski, T.M. , Grosberg, B.M. & Haut, S.R. (2014) Reduction in perceived stress as a migraine trigger: testing the “let‐down headache” hypothesis. Neurology 82, 1395–1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomazzo, E. , Bindila, L. , Remmers, F. , Lerner, R. , Schwitter, C. , Hoheisel, U. & Lutz, B. (2015) Therapeutic potential of inhibitors of endocannabinoid degradation for the treatment of stress‐related hyperalgesia in an animal model of chronic pain. Neuropsychopharmacology 40, 488–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maniyar, F.H. , Sprenger, T. , Schankin, C. & Goadsby, P.J. (2014) The origin of nausea in migraine‐a PET study. J Headache Pain 15, 84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin, R.J. , Hill, M.N. & Gorzalka, B.B. (2014) A critical role for prefrontocortical endocannabinoid signaling in the regulation of stress and emotional behavior. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 42, 116–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morena, M. , Patel, S. , Bains, J.S. & Hill, M.N. (2016) Neurobiological interactions between stress and the endocannabinoid system. Neuropsychopharmacology 41, 80–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulder, E.J. , Van Baal, C. , Gaist, D. , Kallela, M. , Kaprio, J. , Svensson, D.A. , Nyholt, D.R. , Martin, N.G. , MacGregor, A.J. , Cherkas, L.F. , Boomsma, D.I. & Palotie, A. (2003) Genetic and environmental influences on migraine: a twin study across six countries. Twin Res 6, 422–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy‐Grocz, G. , Tar, L. , Bohar, Z. , Fejes‐Szabo, A. , Laborc, K.F. , Spekker, E. , Vecsei, L. & Pardutz, A. (2015) The modulatory effect of anandamide on nitroglycerin‐induced sensitization in the trigeminal system of the rat. Cephalalgia 36, 849–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napadow, V. , Sheehan, J.D. , Kim, J. , Lacount, L.T. , Park, K. , Kaptchuk, T.J. , Rosen, B.R. & Kuo, B. (2013) The brain circuitry underlying the temporal evolution of nausea in humans. Cereb Cortex 23, 806–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker, L.A. , Rock, E.M. & Limebeer, C.L. (2011) Regulation of nausea and vomiting by cannabinoids. Br J Pharmacol 163, 1411–1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker, L.A. , Rock, E.M. , Sticht, M.A. , Wills, K.L. & Limebeer, C.L. (2015) Cannabinoids suppress acute and anticipatory nausea in preclinical rat models of conditioned gaping. Clin Pharmacol Ther 97, 559–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel, S. & Hillard, C.J. (2008) Adaptations in endocannabinoid signaling in response to repeated homotypic stress: a novel mechanism for stress habituation. Eur J Neurosci 27, 2821–2829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rea, K. , Olango, W.M. , Okine, B.N. , Madasu, M.K. , McGuire, I.C. , Coyle, K. , Harhen, B. , Roche, M. & Finn, D.P. (2014) Impaired endocannabinoid signalling in the rostral ventromedial medulla underpins genotype‐dependent hyper‐responsivity to noxious stimuli. Pain 155, 69–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed, M.L. , Fanning, K.M. , Serrano, D. , Buse, D.C. & Lipton, R.B. (2015) Persistent frequent nausea is associated with progression to chronic migraine: AMPP study results. Headache 55, 76–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo, E.B. (2004) Clinical endocannabinoid deficiency (CECD): can this concept explain therapeutic benefits of cannabis in migraine, fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome and other treatment‐resistant conditions? Neuro Endocrinol Lett 25, 31–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarchielli, P. , Pini, L.A. , Coppola, F. , Rossi, C. , Baldi, A. , Mancini, M.L. & Calabresi, P. (2007) Endocannabinoids in chronic migraine: CSF findings suggest a system failure. Neuropsychopharmacology 32, 1384–1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauro, K.M. & Becker, W.J. (2009) The stress and migraine interaction. Headache 49, 1378–1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey, K.A. , Darmani, N.A. & Parker, L.A. (2014) Regulation of nausea and vomiting by cannabinoids and the endocannabinoid system. Eur J Pharmacol 722, 134–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Schueren, B.J. , Van Laere, K. , Gerard, N. , Bormans, G. & De Hoon, J.N. (2012) Interictal type 1 cannabinoid receptor binding is increased in female migraine patients. Headache 52, 433–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodhams, S.G. , Sagar, D.R. , Burston, J.J. & Chapman, V. (2015) The role of the endocannabinoid system in pain In Schaible H.‐G. (ed), Pain Control. Springer, Berlin, pp. 119–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zameel Cader, M. (2013) The molecular pathogenesis of migraine: new developments and opportunities. Hum Mol Genet 22, R39–R44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1: Advantage of the Bayesian system‐based analysis and potential biological explanation of the results.

Table S1: Haplotype frequencies in the CNR1 gene (using the nominally significant SNPs in haploblock 1: rs806366, rs4707436, rs1049353, rs806369), and statistical results of interaction effects between recent negative life events (RLE) and haplotypes on headache with nausea in the total study population.

Figure S1: LD block structure of the investigated subpopulations.

Figure S2: LD block structure of rs806366, rs4707436, rs1049353, rs806369 in the total population.