Abstract

The Ugi four-component reaction (U-4CR) with N-hydroxyimides as a novel carboxylic acid isostere has been reported. This reaction provides straightforward access to α-hydrazino amides. A broad range of aldehydes, amines, isocyanides and N-hydroxyimides were employed to give products in moderate to high yields. This reaction displays N–N bond formation by cyclic imide migration in the Ugi reaction. Thus, N-hydroxyimide is added as a new acid component in the Ugi reaction and broadens the scaffold diversity.

The Ugi reaction (U-4CR) is a widely used multicomponent reaction (MCR) for the synthesis of bis-amides and peptidomimetics.1 This reaction has emerged as a powerful synthetic method for the organic, pharmaceutical, and polymer industries.2 However, it cannot meet the ever-increasing need for molecular complexity and diversity in organic and medicinal chemistry. An increasing demand for novel scaffolds has led to the interest in U-4CR postmodifications and single-reactant replacement (SRR) by isosteres.3 U-4CR postmodifications are useful for the synthesis of various heterocycles and peptidic scaffolds.4 Nevertheless, isostere use in the Ugi reaction is rather limited.5 An amine component could be replaced by secondary amines, hydroxylamines, and hydrazines. As with amines, use of acid isosteres in the Ugi reaction is also limited.

In the Ugi reaction, the carboxylic acid plays several prominent structural roles, including activation of the intermediate imine, the reversible addition to the nitrilium ion, and participation in the irreversible Mumm rearrangement to form the final bis-amide product. Because of carboxylic acid’s substantial role in the reaction, isosteric replacement by other agents is difficult to accomplish. In 1962, Ugi reported the first acid isosteric replacements by inorganic acids, such as hydrazoic acids, cyanates, thiocyanates, etc. (Figure 1).6 To date, only a few acid isosteres have been reported. For example, our group reported the thioacetic acid as an isostere.7 El Kaïm and co-workers reported the phenol as an acid isostere in the Ugi reaction involving Smiles rearrangement to form an N-arylamine.8 Other Ugi–Smiles and similar strategies have been described by El Kaïm (thiophenol),9 Charton (squaric acid),10 and Neo (hydroxycoumarins).11 Further, Lewis acids and CO2 were used as acid isoteres in the U-4CR.5

Figure 1.

Previously reported and new acid isoteres in U-4CR.

As for the related Passerini reaction,12 organic acid isostere replacement has remained largely unexplored for the Ugi-4CR as there are only a few examples of isostere use in the Ugi-4CR for the synthesis of peptidomimetics.5 Therefore, finding new isosteres in U-4CR for the synthesis of diverse and complex peptidomimetic derivatives is of high interest.

We hypothesized that N-hydroxyimides could be used as a novel acid isostere in the U-4CR reaction, which can directly provide the α-hydrazino amides as Ugi reaction products. α-Hydrazino amides are aza analogues of β-peptides and are of interest for several reasons.13 These foldamers exhibit the special hydrazino turn, and the hydrazidic bond is very resistant to protease.14 Hydrazino amides are found in many natural products such as linatine, a vitamin B6 antagonist;15a negamycine, an antibiotic;15b and matlystatins, antimicrobial compounds.15c They also have broad applications in medicinal chemistry including use as proteasome inhibitors,16a antimicrobials,16b DNA and RNA interactors,16c (S)-(−)-carbidopa for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease,17 or as human leukocyte elastase (HLE) inhibitors.18

Hydrazino peptides are mainly synthesized by two methods: first, by using hydrazine derivatives19 and, second, by coupling of an amino group with another amine typically employing oxaziridines.14 The general use of hydrazine and oxaziridine is limited by unavailability of diverse derivatives and their highly toxic and unstable nature. Another drawback is that their synthesis is laborious. Therefore, the development of new methods for the synthesis of this important foldamer is highly desirable.

Herein, we report the successful use of the N-hydroxyimides as an acid isostere in the U-4CR for a direct route to the synthesis of α-hydrazino amides. This is the second example of cyclic imide migration to nitrogen (O → N imide transfer) in the Mumm rearrangement to form an N–N bond. This type of N–O bond breaking and N–N bond formation in a Mumm-type rearrangement has been recently reported.20 This reaction illustrates the use of N-hydroxamic acid for N–N bond formation without phthalimidation.

We started our optimization by using propionaldehyde, benzylamine, cyclohexyl isocyanide, and N-hydroxyphthalimides (NHPI) as model reactants. Reaction in methanol did not form any desired product (Table 1, entry 1). In polar aprotic solvents such as THF and CH3CN, only traces of product were formed (see the Supporting Information for details of optimization conditions). In the polar protic solvent MeOH, the U-3CR product, α-amino amide, was formed as a major product; in contrast, it formed only in trace amounts in solvents such as THF and toluene. This U-3CR product formation might be due to the low acidity of N-hydroxyimide (pKa ∼ 7.5), which functioned only as a catalyst. This observation led us to try a nonpolar solvent and Lewis acid to activate N-hydroxyimide for the further optimization. Indeed, nonpolar solvents such as DCE and toluene allowed moderate product formation of 25% and 20%, respectively, at room temperature.

Table 1. Optimization Conditionsa.

| entry | solvent | temp (°C) | catalyst | time (h) | % yieldb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | MeOH | rt | 12 | ||

| 2 | THF | rt | 12 | trace | |

| 3 | CH3CN | rt | 12 | trace | |

| 4 | DCE | rt | 12 | 25 | |

| 5 | toluene | rt | 12 | 20 | |

| 6c | DCE | rt | ZnCl2 | 22 | |

| 7c | DCE | rt | Sc(OTf)3 | 12 | 15 |

| 8c | DCE | rt | I2 | 12 | 22 |

| 9c | DCE | rt | TMSCl | 12 | 19 |

| 10c | DCE | rt | InCl3 | 12 | 10 |

| 11c | THF | 50 | I2 | 12 | trace |

| 12c | DCE | 50 | ZnCl2 | 12 | nd |

| 13c | toluene | rt | ZnCl2 | 12 | 51 |

| 14c | xylene | rt | ZnCl2 | 12 | 49 |

| 15c | chlorobenzene | rt | ZnCl2 | 12 | 31 |

| 16c | TFE | rt | ZnCl2 | 12 | 38 |

| 17d | DCE | rt | ZnCl2 | 12 | 40 |

| 18d | toluene | rt | ZnCl2 | 12 | 66 |

| 19e | toluene | rt | ZnCl2 | 12 | 47 |

| 20f | toluene | rt | ZnCl2 | 2 | 43 |

| 21g | toluene | rt | ZnCl2 | 2 | 50 |

The reaction was carried out with propionaldehyde (1.0 mmol), benzylamine (1.0 mmol), cyclohexyl isocyanide (1.0 mmol), and N-hydroxyphthalimide (1.5 mmol) in 2 mL of solvent.

Yield of isolated product 5a.

10 mol % of catalyst used.

30 mol % of ZnCl2 used.

50 mol % of ZnCl2 used.

Reaction performed in sonication with 10 mol % of ZnCl2.

Reaction performed in sonication with 30 mol % of ZnCl2. nd = not determined.

Next, we screened various Lewis acids, (Table S2) such as InCl3, I2, Sc(OTf)3, etc. (10 mol %) in DCE as a solvent. We found that ZnCl2 was the best of the screened Lewis acids (Table 1, entries 7–11). An increase in the temperature failed to improve the product yield (Table 1, entries 11 and 12). In further solvent screening with ZnCl2, (Table S3), we observed that toluene and xylene gave similar yields, 51% and 49%, respectively (Table 1, entries 13 and 14). The nature of the solvent played a critical role in the success of the reaction. Next, we performed a catalyst equivalence study in toluene as solvent. An increase in the catalyst quantity to 30 mol % gave the best yield of 66% (Table 1, entry 18). However, a further increase in the quantity of ZnCl2 to 50 mol % gave a lower yield, 47% (Table 1, entry 19). The use of sonication in this reaction did not have any effect on product yield (Table 1, entries 20 and 21).12a

With these optimized conditions in hand, next we examined the generality of this U-4CR by using various aldehydes, amines, isocyanides, and N-hydroxyimides (Table 2). Aliphatic aldehydes offered good yields, up to 78% (Table 2, entries 1–3). Aromatic aldehydes are also useful substrates in this reaction (Table 2, entries 6–9).

Table 2. Substrate Scopea.

Reaction conditions: 1 (1.0 mmol), 2 (1.0 mmol), 3 (1.0 mmol), and 4 (1.5 mmol), ZnCl2 (30 mol %) in toluene (2 mL) at rt for overnight.

Isolated yield.

1.5 equiv of triethylamine used.

Electron-withdrawing and -donating groups in aromatic aldehydes at different positions such as ortho and para provided moderate to good yields. Amines with protected functional groups like acetal and halogens were well-tolerated in this reaction, affording moderate to good yields of the products (Table 2, entries 3, 4, and 6). The acid-protected amino acid β-alanine ester gave only 18% yield (Table 2, entry 5). Various aliphatic and aromatic isocyanides like cyclohexyl, phenylethyl, 2-nitrobenzyl, benzyl, 4-methoxyphenyl, and β-cyanoethyl were well-suited within the developed methodology. Among N-hydroxyimides, N-hydroxysuccinimides (NHS) also proceeded smoothly similarly to NHPI and gave 48–59% yield (Scheme 1, 5n–p). However, the reaction with hydroxybenzotriazole (HOBt) resulted in only trace product formation (Scheme 1, 5q).

Scheme 1. N-Hydroxyimide Scope.

A broad functional group tolerance in this reaction could be of interest for the postmodification condensations. Thus, among the vast number of possible postmodification reactions with this modified U-4CR, we attempted several. Hydrazines are important intermediates for the synthesis of many heterocycles and scaffolds.19 The U-4CR product (5d) treatment with hydrazine hydrate deprotects the NHPI and forms the free hydrazine derivatives 6.12a We obtained free hydrazine in a good yield of 64% after overnight reaction (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2. Deprotection toward Hydrazine Formation.

Next, we turned our attention to creating access for pharmaceutically important α-amino amide molecules. We converted the U-4CR product (5p) to U-3CR product α-amino amide 7 in good yield (73%). This AlCl3-catalyzed reaction cleaved the N–N bond (Scheme 3) to form the final product.21

Scheme 3. Deprotection toward α-Amino Amide.

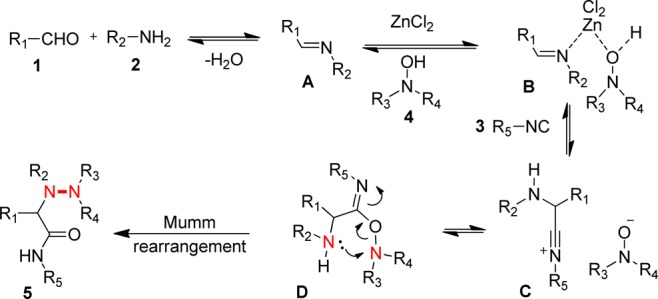

We did not carry out detailed mechanistic studies but envision the following mechanism (Scheme 4). ZnCl2 activates an imine A to allow the nucleophilic addition of isocyanide 3 to form the nitrilium intermediate C. The hydroxamate nucleophilicly traps the nitrilium intermediate C. Finally, this intermediate D undergoes an irreversible Mumm-like N → N migration to form the α-hydrazino amide 5.

Scheme 4. Anticipated Mechanism for the Ugi–N-Hydroxyimide Reaction.

In conclusion, we have reported N-hydroxyimides as novel acid isosteres in the U-4CR toward the one-step synthesis of α-hydrazino amides via N–N bond formation. This mild and general reaction requires catalytic amounts of ZnCl2. This protocol uses readily available N-hydroxy imides, which replace the toxic and unstable hydrazines/oxaziridine use for the synthesis of α-hydrazino amides. The method is applicable for a wide range of aldehydes and amines and has the potential for multiple postmodifications. Such scaffolds will be useful to fill the screening decks of the European Lead Factory (ELF).22 Moreover, as this reaction has significant potential in peptidomimetics synthesis, studies on postmodification reactions are now in progress.

Acknowledgments

We thank the University of Groningen. The Erasmus Mundus Scholarship “Svaagata” is acknowledged for a fellowship to A.C. The work was financially supported by the NIH (2R01GM097082-05) and by the Innovative Medicines Initiative (Grant Agreement No. 115489). Funding has also been received from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under MSC ITN “Accelerated Early stage drug dIScovery” (AEGIS) (Grant Agreement No. 675555).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b00205.

General experimental procedures; compound characterization data; 1H and 13C spectra of all compounds (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- a Ugi I.; Werner B.; Domling A. Molecules 2003, 8, 53–66. 10.3390/80100053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Domling A.; Ugi I. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2000, 39, 3168–3210. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Ugi I.; Domling A.; Horl W. Endeavour 1994, 18, 115–122. 10.1016/S0160-9327(05)80086-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Domling A. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2002, 6, 306–313. 10.1016/S1367-5931(02)00328-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Hulme C.; Gore V. Curr. Med. Chem. 2003, 10, 51–80. 10.2174/0929867033368600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Domling A. Chem. Rev. 2006, 106, 17–89. 10.1021/cr0505728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Domling A.; Wang W.; Wang K. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 3083–3135. 10.1021/cr100233r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Zarganes-Tzitzikas T.; Chandgude A. L.; Domling A. Chem. Rec. 2015, 15, 981–996. 10.1002/tcr.201500201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koopmanschap G.; Ruijter E.; Orru R. V. A. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2014, 10, 544–598. 10.3762/bjoc.10.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunderhaus J. D.; Martin S. E. Chem. - Eur. J. 2009, 15, 1300–1308. 10.1002/chem.200802140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Ruijter E.; Scheffelaar R.; Orru R. V. A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 6234–6246. 10.1002/anie.201006515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b El Kaim L.; Grimaud L. Tetrahedron 2009, 65, 2153–2171. 10.1016/j.tet.2008.12.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ugi I. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1962, 1, 8–21. 10.1002/anie.196200081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heck S.; Domling A. Synlett 2000, 424–426. 10.1055/s-2000-6517. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- El Kaim L.; Grimaud L.; Oble J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 7961–7964. 10.1002/anie.200502636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barthelon A.; El Kaïm L.; Gizolme M.; Grimaud L. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 2008, 5974–5987. 10.1002/ejoc.200800859. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aknin K.; Gauriot M.; Totobenazara J.; Deguine N.; Deprez-Poulain R.; Deprez B.; Charton J. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012, 53, 458–461. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2011.11.077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neo A. G.; Castellano T. G.; Marcos C. F. Synthesis 2015, 47, 2431–2438. 10.1055/s-0034-1380436. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Chandgude A. L.; Domling A. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 6396–6399. 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b03293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Soeta T.; Kojima Y.; Ukaji Y.; Inomata K. Org. Lett. 2010, 12, 4341–4343. 10.1021/ol101763w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Soeta T.; Matsuzaki S.; Ukaji Y. Chem. - Eur. J. 2014, 20, 5007–5012. 10.1002/chem.201304618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Soeta T.; Ukaji Y. Chem. Rec. 2014, 14, 101–116. 10.1002/tcr.201300021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Salaun A.; Potel M.; Roisnel T.; Gall P.; Le Grel P. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 70, 6499–6502. 10.1021/jo050938g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Gunther R.; Hofmann H. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 247–255. 10.1021/ja001066x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lelais G.; Seebach D. Helv. Chim. Acta 2003, 86, 4152–4168. 10.1002/hlca.200390342. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Klosterman H. J.; Lamoureux G. L.; Parsons J. L. Biochemistry 1967, 6, 170–177. 10.1021/bi00853a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b McKinney D. C.; Basarab G. S.; Cocozaki A. I.; Foulk M. A.; Miller M. D.; Ruvinsky A. M.; Scott C. W.; Thakur K.; Zhao L.; Buurman E. T.; Narayan S. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2015, 6, 930–935. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.5b00205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Tanzawa K.; Ishii M.; Ogita T.; Shimada K. J. Antibiot. 1992, 45, 1733–1737. 10.7164/antibiotics.45.1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Bordessa A.; Keita M.; Marechal X.; Formicola L.; Lagarde N.; Rodrigo J.; Bernadat G.; Bauvais C.; Soulier J. L.; Dufau L.; Milcent T.; Crousse B.; Reboud-Ravaux M.; Ongeri S. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 70, 505–524. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.09.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Laurencin M.; Amor M.; Fleury Y.; Baudy-Floc’h M. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 10885–10895. 10.1021/jm3009037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Suc J.; Tumir L. M.; Glavas-Obrovac L.; Jukic M.; Piantanida I.; Jeric I. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2016, 14, 4865–4874. 10.1039/C6OB00425C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vickers S.; Stuart E. K.; Hucker H. B.; Vandenheuvel W. J. A. J. Med. Chem. 1975, 18, 134–138. 10.1021/jm00236a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy L.; Vidal J.; Collet A.; Amour A.; Reboud-Ravaux M. J. Med. Chem. 1998, 41, 4833–4843. 10.1021/jm980419o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Suc J.; Baric D.; Jeric I. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 99664–99675. 10.1039/C6RA23317A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Hashimoto T.; Kimura H.; Kawamata Y.; Maruoka K. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 7279–7281. 10.1002/anie.201201905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Krasavin M.; Bushkova E.; Parchinsky V.; Shumsky A. Synthesis 2010, 2010, 933–942. 10.1055/s-0029-1219274. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Busnel O.; Bi L. R.; Dali H.; Cheguillaume A.; Chevance S.; Bondon A.; Muller S.; Baudy-Floc’h M. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 70, 10701–10708. 10.1021/jo051585o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Article published during review process of this article:Mercalli V.; Nyadanu A.; Cordier M.; Tron G. C.; Grimaud L.; El Kaim L. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53, 2118–2121. 10.1039/C6CC10288C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikugawa Y.; Aoki Y.; Sakamoto T. J. Org. Chem. 2001, 66, 8612–8615. 10.1021/jo016124r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Mullard A. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2013, 12, 173–175. 10.1038/nrd3956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Karawajczyk A.; Hamza D.; Kalliokoski T.; Pouwer K.; Morgentin R.; Nelson A.; Müller G.; Piechot D.; Tzalis D. Drug Discovery Today 2015, 20, 1310–1316. 10.1016/j.drudis.2015.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Paillard G.; Cochrane P.; Jones P. S.; Caracoti A.; van Vlijmen H.; Pannifer A. D. Drug Discovery Today 2016, 21, 97–102. 10.1016/j.drudis.2015.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Besnard J.; Jones P. S.; Hopkins A. L.; Pannifer A. D. Drug Discovery Today 2015, 20, 181–186. 10.1016/j.drudis.2014.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Nelson A.; Roche D. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2015, 23, 2613. 10.1016/j.bmc.2015.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.