Abstract

On social media, users can easily share their feelings, thoughts, and experiences with the public, including people who they have no previous interaction with. Such information, though often embedded in a stream of others’ news, may influence recipients’ perception toward the discloser. We used a special design that enables a quasi-experience of SNS browsing, and examined if browsing other’s posts in a news stream can create a feeling of familiarity and (even) closeness toward the discloser. In addition, disclosure messages can vary in the degree of intimacy (from superficial to intimate) and narrativity (from a random blather to a story-like narrative). The roles of disclosure intimacy and narrativity on perceived closeness and social attraction were examined by a 2 × 2 experimental design. By conducting one lab study and another online replication, we consistently found that disclosure frequency, when perceived as appropriate, predicted familiarity and closeness. The effects of disclosure intimacy and narrativity were not stable. Further exploratory analyses showed that the roles of disclosure intimacy on closeness and social attraction were constrained by the perceived appropriateness, and the effects of narrativity on closeness and social attraction were mediated by perceived entertainment value.

Keywords: Self-disclosure, Intimacy, Narrativity, Social attraction, Closeness, Social media

Highlights

-

•

Frequent self-disclosure increases feeling of familiarity and closeness.

-

•

Intimate disclosure can increase closeness, but more often reduces social attraction.

-

•

The effects of intimate disclosure are constrained by perceived appropriateness.

-

•

Disclosure narrativity tends to increase perceived closeness and social attraction.

-

•

The effects of narrativity are mediated by perceived entertainment value.

1. Introduction

“Merely looking at a stranger’s Twitter or Facebook feed isn’t interesting, because it seems like blather. Follow it for a day, though, and it begins to feel like a short story; follow it for a month, and it’s a novel.”

Although many social media platforms are mainly used for maintaining existing relationships, it is also common to stumble across the messages of strangers. On Twitter for example, it is relatively common to follow people one knows only online (Utz, 2016). A survey among Twitter users has shown that people develop ambient intimacy, i.e. a feeling of closeness to others followed on social media, for some of the people they follow on Twitter (Lin, Levordasha, & Utz, 2016). Classical studies on relationship formation focus on the role of intimacy in self-disclosure (Altman & Taylor, 1973), although studies on (semi-) public social media have shown that entertaining posts can also create a feeling of closeness (Lin et al., 2016, Utz, 2015). However, as these studies have been correlational and relied on self-reported judgments/recall of the content of posts, it is not clear which factors drive the development of a feeling of closeness. To answer this question, we conducted two experiments in which we varied the number of posts and manipulated for the target person not only the intimacy but also the narrativity of self-disclosure. The latter factor has hitherto been neglected, although the quote at the beginning of this paper indicates that narrativity and story value of posts might matter. Additionally, we look at potential influence factors such as perceived appropriateness and entertainment value of posts. By experimentally disentangling the role of intimacy and narrativity, we contribute to a better understanding of the processes underlying relationship formation on social media.

In the following paragraphs, we will introduce the concepts of self-disclosure frequency, intimacy, and narrativity on social media, and its difference to self-disclosure in traditional one-to-one communication. Relevant previous research on the effects of self-disclosure on familiarity, closeness, and social attraction will be discussed.

2. Theoretical background

2.1. Self-disclosure on social media and its difference to self-disclosure offline

Conceptually speaking, broadcasting status updates/posts on social media that contain any form of self-information can be treated as self-disclosure (Lin et al., 2016). The posts could contain descriptive information such as what one has done today, and/or evaluative information such as how one feels about an event. In previous research, the degree of self-disclosure was often assessed along two dimensions: disclosure breadth (e.g., the amount of self-relevant statements made during an interaction) and disclosure depth (i.e., the level of disclosure intimacy) (Altman & Taylor, 1973).

Public self-disclosures on social media have some unique properties compared to self-disclosure in traditional one-to-one communication. First, when the disclosing self-information is highly intimate, it is more likely to be perceived as inappropriate when one broadcasts it online than discloses it privately (Bazarova, 2012); therefore, intimate self-disclosure on social media often decreases interpersonal attraction (Baruh & Cemalcılar, 2015). Second, public self-disclosure is often not directed to a single person, but simultaneously to several people. Disclosure recipients might not feel addressed in this case; and self-disclosure might have smaller effects on relationships (Burke & Kraut, 2014). Third, public self-disclosure from a specific person is often embedded in a stream of others’ information; hence disclosure recipients may not pay enough attention to it.

In addition to the two dimensions of self-disclosure breadth and depth, we assume that self-disclosure narrativity is also important in the context of social media. We will discuss the role of disclosure intimacy and narrativity later, and first introduce the literature on the effects of self-disclosure frequency on familiarity, closeness, and social attraction. We chose these three dependent variables because they were often discussed in previous literature (Norton et al., 2013, Sprecher et al., 2012), but conceptually they are slightly different from each other. In this paper, familiarity refers to the state of being accustomed to something or someone. It is knowledge of something or someone, which mainly depends on disclosure frequency (Finkel et al., 2015, pp. 1–39), regardless of the valence. Closeness and social attraction are more likely to be influenced by the content of self-disclosure. Closeness covers the emotional facet, whereas social attraction refers to the behavioral component, e.g. wanting to have a coffee with the target.

2.2. Effects of self-disclosure frequency on perceived familiarity, closeness, and social attraction

Even though there are some differences in private and public self-disclosure, recent studies indicated that browsing social media helps to enhance familiarity, creates awareness/knowledge of online contacts (Levordashka & Utz, 2016), and generates a feeling of closeness (Lin et al., 2016). Familiarity is generated when an individual has a certain level of exposure to the target person (Finkel et al., 2015, pp. 1–39). The amount of self-disclosure can be considered as operationalization of exposure. Therefore, a greater amount of public self-disclosure on social media should also generate a higher level of familiarity.

When it comes to closeness and attraction, findings are less consistent. In private conversations, when perceived as appropriate, greater amounts of disclosure information were often associated with more liking of the discloser (for review, see Collins & Miller, 1994). For unacquainted strangers, self-disclosure often leads to more closeness (A. Aron, Melinat, Aron, Vallone, & Bator, 1997), which creates familiarity-based liking (Berger and Calabrese, 1975, Zajonc, 1968), and positive interpersonal impressions such as social attraction (Sprecher et al., 2012). This is due to “mere exposure effect” and “uncertainty reduction theory”. The former asserted that the more frequently one is exposed to a certain thing or person, the more likable that thing or person appears to be (Moreland and Zajonc, 1982, Zajonc, 1968). The latter theory indicated that the more one is exposed to other’s self-disclosure, the more uncertainty is reduced, therefore liking is increased (Sunnafrank, 1986).

However, other researchers have found that more information about a person may decrease liking due to a higher level of perceived dissimilarity. This is also referred to as “less is more” hypothesis (Norton, Frost, & Ariely, 2007). The mixed findings can be explained by the information-processing approach of attraction (Ajzen, 1977, Dalto et al., 1979). It suggests that liking is determined by having positive beliefs about an individual: the more positive the beliefs, the greater the attraction; however, if the content of self-discloser leads to negative beliefs (e.g., due to perceived dissimilarity or inappropriateness), the attraction should be decreased (Ajzen, 1977).

Similar to the familiarity and attraction link, we assume that, after reading other’s public self-disclosure on social media, a feeling of closeness can be generated only under certain conditions (i.e., when positive beliefs are generated). In this case, in addition to disclosure frequency, the content of self-disclosure is more important in predicting social attraction.

2.3. Self-disclosure intimacy and interpersonal attraction

In offline relationship building, disclosure intimacy plays a central role (Collins & Miller, 1994). But it is still a debatable question whether disclosing intimate information promotes or undermines interpersonal attraction and closeness on SNS. For existing interpersonal relationships, researchers have found that receiving a larger proportion of superficial disclosures decreases relationship satisfaction (Rains, Brunner, & Oman, 2014). Self-disclosure on SNS, when perceived as more intimate, increases the feeling of connection toward existing online friends (Lin et al., 2016, Utz, 2015). However, such a positive effect of disclosure intimacy on building interpersonal relationships is stronger for messages on private channels than for public status updates (Bazarova, 2012). In the context of public status updates, the entertainment value of updates also matters (Utz, 2015).

We focus on situations in which an individual had no previous interactions with a target, using a so-called zero-acquaintance paradigm in which perceivers make judgments about strangers without having the opportunity to interact (Albright, Kenny, & Malloy, 1988). Baruh and Cemalcılar (2015) have found that broadcasting intimate disclosure messages may attract more attention but not necessarily increase attraction.

However, it is important to take the role of appropriateness into account, as intimate disclosure in public is often perceived as inappropriate (Bazarova, 2012). In Baruh and Cemalcılar’s (2015) study, the level of disclosure appropriateness was altered essentially when the level of disclosure intimacy was manipulated. It was difficult to conclude whether the decreased attraction is because of the high-intimacy or high-inappropriateness.

The current study aims to examine the role of disclosure intimacy by minimizing the difference in the perceived appropriateness of high- and low-intimacy disclosure messages. We used stimulus material that was judged as appropriate in a pretest, and expected that under these circumstances intimate self-disclosure should have a positive role in increasing closeness and social attraction.

2.4. Narrativity and interpersonal attraction

A second factor that has been neglected in prior research on the development of closeness on social media is narrativity. We conceptualized narrative self-disclosure as revealing information about oneself in a story-telling way. On social media, pieces of self-disclosure information are treated as high in narrativity when they, taken together, are able to form a continuous and coherent story. Vorderer (2016) argued that narratives play a central role in new media. For example, people are transported into the narratives in novels or movies (Bilandzic, 2006, Green et al., 2004), and they may develop a feeling of closeness to the character by merging into the narrative.

Compared with the same events that are portrayed through less narrativity, higher levels of narrativity often correspond to greater vividness, ease of narrative understanding, engagement, and emotional responses (Busselle & Bilandzic, 2009). Considering the strong desire of people for stories, we thus assume that narrative self-disclosure should have a positive effect on perceived closeness and social attraction.

In sum, we developed the following hypotheses.

H1

The amount of public self-disclosure increases familiarity.

H2

Intimate self-disclosure, when perceived as appropriate, increases (a) perceived closeness and (b) social attraction.

H3

Narrative self-disclosure increases (a) perceived closeness and (b) social attraction.

In order to examine these hypotheses, two pretests and two studies were conducted. The two pretests were conducted in order to create proper stimuli before conducting the main studies. The initial main study was followed up with an online version of the same study: Study 1 was conducted in a lab and with a limited amount of participants; Study 2 aimed to replicate the results of Study 1, and was an online questionnaire with a larger sample size.

3. Study 1

3.1. Methods

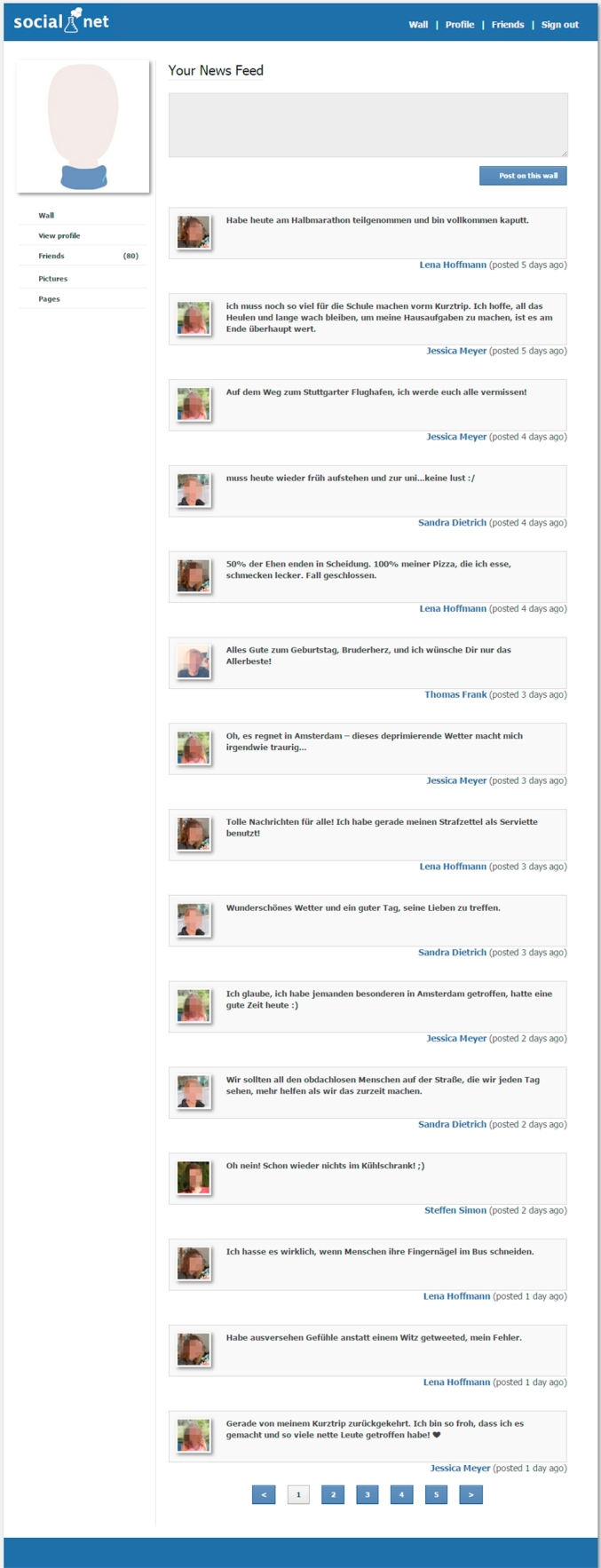

In order to examine H1, a special design that enables a quasi-experience of SNS browsing was applied (see a sample of the stimuli in Fig. 1). We created a fake SNS called Social Net, and mocked-up web pages that resemble the layout of Facebook News Feed, including posts, user names, and profile pictures. In our scenario, the target discloser posted 5 times, and the other four disclosers posted 5 times, 3 times, 1 time, and 1 time, respectively.

Fig. 1.

A sample of stimuli for the condition of high-intimacy & high-narrativity (in German). The profile pictures and the basic layout of the web pages were originally taken from Social Lab (Garaizar & Reips, 2014), which is an open source social network software developed for research. Profile pictures were made unrecognizable only for publication.

In order to test H2 and H3, we adopted a 2 (high- vs. low-intimacy disclosure) × 2 (high- vs. low-narrativity disclosure) between-subject design. We created four versions of disclosure messages for the target discloser. In each condition, the five manipulated disclosure posts of a target discloser (as described in Appendix A) were embedded (in the same order) in another ten distracting posts from the other four disclosers/distractors (see Fig. 1). These ten distracting posts were identical across all conditions.

3.1.1. Pretests

Two pretests were conducted in order to compose the stimuli for the main experiment (see in Appendix A). In the first pretest, 56 disclosure messages were selected and adapted from real Tweets on Twitter. Sixty-four German participants evaluated the levels of intimacy and appropriateness for each individual message after translation into German.

Based on these results, we composed four versions of target posts (i.e., disclosure messages of the target person) after adjusting the level of narrativity. This version of posts was similar to the final version of posts in Appendix A. We manipulated the level of intimacy by adding information about one’s emotions, inner thoughts, and beliefs; and we manipulated the level of narrativity by adding more details and transitional descriptions. The topic of each message remained the same.

In the second pretest, the levels of disclosure narrativity, intimacy, and appropriateness of each stimulus were assessed by another 52 German participants using a between-subject design. The results of the second pretest indicated that such stimuli can successfully manipulate the levels of disclosure intimacy and narrativity accordingly, and the levels of appropriateness were above the middle point of 4 in all conditions.

3.1.2. Procedure and materials

In Study 1, participants were asked to complete an online questionnaire in the lab. They were asked to imagine that they just created an account on a newly launched SNS called “Social Net” and had followed some other users’ profile as recommended by the system. They were also informed that many Social Net users feel at ease to keep their postings as a digital public diary on that SNS. This instruction helped us to investigate the effect of self-disclosure intimacy when public self-disclosure is legitimized and more likely to be perceived as appropriate. It hopefully can minimize the difference of the appropriateness level between high- and low-intimacy conditions. Then participants were randomly assigned into one of the four conditions, and they were allowed to browse the stimuli as long as they wished to.

As soon as they finished browsing, the levels of familiarity were measured by asking “how familiar do you feel to the following profile owners”, with a continuous rating scale (1–7). Ten profiles were shown in the first column of the question matrix (in a randomized order): the profiles of the five disclosers that were shown in the stimulus and five new profiles that served as distractors. Participants could choose “do not remember” if they felt unfamiliar with the profile owner, and they were supposed to choose that option for the distractors.

Perceived closeness was assessed in two ways. First, the five profile pictures of the disclosers were shown again with the following instruction: “Compared to other users on Social Net, how close do you feel to the following profile owners”. Participants could score between 1 and 7, or choose “no impression” if they could not recall. Second, immediately after the one-item measure of closeness, the perceived closeness to the target discloser was measured by using the propinquity scale (Walther & Bazarova, 2008) with a 7-point semantic differential scale (see more information about measurements in Appendix B). In addition, perceived social attraction of the target was measured by social attraction scale with a 7-point Likert scale (McCroskey & McCain, 1974).

Then the five posts of the target discloser (target posts) were shown again, and participants were asked to evaluate the posts of the target discloser with several seven-point semantic differential scales. The perceived levels of intimacy and appropriateness for the message sets were measured with scales used in Bazarova’s (2012) study. Disclosure narrativity of the target posts was measured with three self-created items about disclosure coherence (e.g., “not coherent-coherent”). Previous research found that the entertainment value of messages significantly predicts the feeling of closeness to the discloser on social media (Lin et al., 2016, Utz, 2015). Therefore, we also measured the perceived entertainment value of the target posts with one-item for exploratory purposes.

A summary of the items for these measurements and the Cronbach’s alphas are reported in Appendix B. Other demographical information such as age, gender, as well as social media usage behavior was measured at the end of the questionnaire.

3.1.3. Sample

Participants, in both pretests and the first study, were recruited from a local panel in Germany. Participants should be a social media user and 18 years and older, and they were paid according to a standard of 8 Euro/hour. Although we initially aimed for a sample size of 160, only 145 participants completed the main experiment after we extended the lab study for another three weeks.

In order to prevent participants clicking through the stimuli without browsing, we dropped the cases in which participants spent less than 30 s in reading each stimulus. We estimated each status update would take about 2 s to skim through; therefore 15 posts might take 30 s. This selection criteria resulted in a final sample of 139 (29 males; Mage = 23.58 years; SD = 4.29 years).

3.2. Results

3.2.1. The effects of disclosure frequency on familiarity and closeness

Table 1 depicts the descriptive results for the degrees of familiarity with the five existing and the five new profile owners. Out of 139 participants, only 5 participants (1.4%) reported “do not remember” seeing the target profile owner, whereas, for those distracting new profiles, more than 101 participants (72.7%) correctly recognized that they were not shown in the stimuli before. In addition, the level of familiarity with the target discloser (M = 4.69, SD = 1.86) was already higher than the level of familiarity with the third discloser who posted three times (M = 4.06, SD = 1.67), t(124) = 4.81, p < 0.001, let alone those who disclosed less often (see more comparison information in Table 1). These results supported H1.

Table 1.

Results for familiarity of profile owners in Study 1 (n = 139).

| Description of the profile owner (No. of posts in shown stimuli) | No. of participants clicked “do not remember” | Mean of familiarity | SD of familiarity | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target discloser (5) | 5 | 4.72a | 1.86 | 1 | 7 |

| Other discloser (5) | 1 | 4.60a | 1.81 | 1 | 7 |

| Other discloser (3) | 10 | 4.03b | 1.67 | 1 | 7 |

| Other discloser (1) | 36 | 2.74c | 1.61 | 1 | 7 |

| Other discloser (1) | 35 | 2.70c | 1.61 | 1 | 7 |

| Non-discloser (0) | 103 | 2.11 | 1.53 | 1 | 7 |

| Non-discloser (0) | 102 | 2.05 | 1.15 | 1 | 4 |

| Non-discloser (0) | 105 | 2.15 | 1.05 | 1 | 5 |

| Non-discloser (0) | 120 | 1.47 | 1.22 | 1 | 6 |

| Non-discloser (0) | 114 | 1.76 | 1.23 | 1 | 5 |

Note: The number in brackets stand for the total amount of posts by that discloser in each stimulus. For the first five disclosers, different superscript letters indicate statistically significant group differences (p < 0.05).

We also measured the feelings of closeness to the five disclosers (see results in Table 2). Similar to the pattern of familiarity, participants felt closer to the profiles owners who disclose more frequently: the target profile owner who posted five times (M = 3.64, SD = 1.85) was perceived as closer compared to the profile owner who posted three times (M = 3.14, SD = 1.60), t(129) = 3.06, p = 0.001, who was in turn perceived as emotionally closer than the two disclosers who posted less frequently (see more information in Table 2).

Table 2.

Results for closeness of profile owners in Study 1 (n = 139).

| Description of the profile owner (No. of posts in shown stimuli) | No. of participants clicked “no impression” | Mean of closeness | SD of closeness | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target discloser (5) | 4 | 3.62a | 1.82 | 1 | 7 |

| Other discloser (5) | 3 | 3.71a | 1.83 | 1 | 7 |

| Other discloser (3) | 6 | 3.14b | 1.61 | 1 | 6 |

| Other discloser (1) | 29 | 2.15c | 1.38 | 1 | 7 |

| Other discloser (1) | 33 | 1.91d | 1.22 | 1 | 7 |

Note: The number in brackets stands for the total amount of posts by that discloser in each stimulus. Different superscript letters indicate statistically significant group differences (p < 0.05).

3.2.2. Manipulation check

Descriptive results for the key variables can be found in Table 3, and correlation statistics can be found in Table 4. The results of the manipulation check showed that we manipulated the disclosure intimacy and narrativity successfully. A two-way ANOVA showed participants in the high-intimacy condition perceived the target posts as more intimate (M = 5.69, SD = 0.91) than that in the low-intimacy condition (M = 4.49, SD = 1.08), F(1, 135) = 49.67, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.269. There was no main effect of narrativity condition, nor an interaction effect for perceived intimacy.

Table 3.

Descriptive results for four conditions in Study 1 and Study 2.

| High-intimacy & low-narrativity | Low-intimacy & low-narrativity | High-intimacy & high-narrativity | Low-intimacy & high-narrativity | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study 1 | ||||||

| Perceived intimacy | Mean | 3.70 | 4.10 | 5.98 | 6.06 | 4.95 |

| SD | 1.44 | 1.31 | 1.04 | 0.90 | 1.60 | |

| Perceived coherence | Mean | 5.72 | 4.39 | 5.66 | 4.59 | 5.11 |

| SD | 0.95 | 1.01 | 0.88 | 1.14 | 1.16 | |

| Perceived appropriateness | Mean | 4.20 | 4.69 | 4.57 | 4.96 | 4.60 |

| SD | 1.15 | 1.33 | 1.02 | 1.21 | 1.20 | |

| Perceived entertainment value | Mean | 3.24 | 2.58 | 3.97 | 3.88 | 3.42 |

| SD | 1.88 | 1.50 | 1.56 | 1.49 | 1.70 | |

| Closeness | Mean | 4.14 | 2.50 | 3.88 | 3.79 | 3.62 |

| SD | 1.87 | 1.38 | 1.79 | 1.79 | 1.82 | |

| Propinquity | Mean | 3.81 | 3.03 | 3.62 | 3.91 | 3.60 |

| SD | 1.60 | 1.51 | 1.60 | 1.41 | 1.56 | |

| Attraction | Mean | 4.00 | 4.55 | 4.05 | 5.03 | 4.40 |

| SD | 1.40 | 1.30 | 1.43 | 1.24 | 1.40 | |

| n | 37 (37) | 33 (30) | 35 (34) | 34 (34) | 139 (135) | |

| Study 2 | ||||||

| Perceived intimacy | Mean | 3.72 | 3.87 | 5.83 | 6.13 | 4.93 |

| SD | 1.44 | 1.48 | 1.21 | 0.99 | 1.69 | |

| Perceived coherence | Mean | 5.08 | 4.15 | 5.47 | 4.59 | 4.83 |

| SD | 1.36 | 1.22 | 1.13 | 1.26 | 1.34 | |

| Perceived appropriateness | Mean | 4.27 | 4.83 | 4.59 | 5.07 | 4.70 |

| SD | 1.12 | 1.16 | 1.19 | 1.14 | 1.19 | |

| Perceived entertainment value | Mean | 3.08 | 2.64 | 3.85 | 3.62 | 3.32 |

| SD | 1.12 | 1.55 | 1.82 | 1.68 | 1.73 | |

| Closeness | Mean | 3.10 | 3.25 | 3.47 | 3.71 | 3.39 |

| SD | 1.67 | 1.71 | 1.95 | 1.75 | 1.78 | |

| Propinquity | Mean | 3.38 | 3.34 | 3.63 | 3.71 | 3.52 |

| SD | 1.46 | 1.42 | 1.48 | 1.43 | 1.45 | |

| Attraction | Mean | 4.14 | 4.37 | 4.43 | 4.78 | 4.44 |

| SD | 1.35 | 1.28 | 1.42 | 1.14 | 1.32 | |

| n | 106 (98) | 102 (92) | 110 (99) | 115 (109) | 433 (398) | |

Note: The sample size (n) in brackets stands for the sample size for closeness (as some participants selected “no impression”).

Table 4.

Pairwise correlations for variables in Study 1 and Study 2.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study 1 | ||||||||

| 1. Manipulated intimacy(1 = high, 0 = low) | 1 | |||||||

| 2. Manipulated narrativity (1 = high, 0 = low) | −0.021 | 1 | ||||||

| 3. Perceived coherence | −0.089 | 0.668∗∗∗ | 1 | |||||

| 4. Perceived intimacy | 0.518∗∗∗ | 0.016 | 0.022 | 1 | ||||

| 5. Perceived appropriateness | −0.188∗ | 0.141 | 0.314∗∗∗ | −0.290∗∗ | 1 | |||

| 6. Perceived entertainment value | 0.106 | 0.295∗∗ | 0.328∗∗∗ | 0.191∗ | 0.298∗∗∗ | 1 | ||

| 7. One-item closeness | 0.228∗∗ | 0.120 | 0.134 | 0.183∗ | 0.187∗ | 0.413∗∗∗ | 1 | |

| 8. Propinquity | 0.077 | 0.105 | 0.171∗ | 0.164 | 0.266∗∗ | 0.433∗∗∗ | 0.727∗∗∗ | 1 |

| 9. Attraction | −0.276∗∗ | 0.098 | 0.253∗∗ | −0.168∗ | 0.480∗∗∗ | 0.431∗∗∗ | 0.393∗∗∗ | 0.535∗∗∗ |

| Study 2 | ||||||||

| 1. Manipulated intimacy(1 = high, 0 = low) | 1 | |||||||

| 2. Manipulated narrativity (1 = high, 0 = low) | −0.021 | 1 | ||||||

| 3. Perceived coherence | −0.081 | 0.647∗∗∗ | 1 | |||||

| 4. Perceived intimacy | 0.334∗∗∗ | 0.148∗∗ | 0.243∗∗∗ | 1 | ||||

| 5. Perceived appropriateness | −0.219∗∗∗ | 0.121∗ | 0.346∗∗∗ | −0.123∗ | 1 | |||

| 6. Perceived entertainment value | 0.089 | 0.252∗∗∗ | 0.362∗∗∗ | 0.244∗∗∗ | 0.335∗∗∗ | 1 | ||

| 7. One-item closeness | −0.060 | 0.119∗ | 0.200∗∗∗ | 0.112∗ | 0.272∗∗∗ | 0.272∗∗∗ | 1 | |

| 8. Propinquity | −0.010 | 0.107∗ | 0.223∗∗∗ | 0.118∗ | 0.340∗∗∗ | 0.340∗∗∗ | 0.668∗∗∗ | 1 |

| 9. Attraction | −0.116∗ | 0.134∗∗ | 0.263∗∗∗ | 0.107∗ | 0.431∗∗∗ | 0.431∗∗∗ | 0.504∗∗∗ | 0.573∗∗∗ |

∗p < 0.05. ∗∗p < 0.01. ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

Another two-way ANOVA showed that participants in the high-narrativity condition perceived the target posts as more coherent as a story (M = 6.02, SD = 0.96) than that in the low-narrativity condition (M = 3.89, SD = 1.39), F(1, 135) = 155.61, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.447. As expected, there was no main effect of intimacy condition, nor an interaction effect for perceived coherence.

In previous research, disclosure appropriateness was highly associated with disclosure intimacy on social media (Bazarova, 2012). Therefore, we also examined whether there is a group difference of appropriateness using a two-way ANOVA. The result showed that participants in the high-intimacy condition (M = 4.38, SD = 1.10) also perceived the disclosure as slightly less appropriate than that in the low-intimacy condition (M = 4.83, SD = 1.27), F(1, 135) = 4.88, p = 0.029, ηp2 = 0.035. This result showed that it is difficult to disentangle the concepts of perceived intimacy and perceived appropriateness in the context of public self-disclosure on social media. Even though we tried to make intimate public self-disclosure as appropriate as possible, it was still rated as slightly less appropriate than non-intimate public self-disclosure.

Most importantly, the mean values of disclosure appropriateness were above four in all conditions, indicating that we succeeded in constructing appropriate posts. Moreover, the manipulations of disclosure intimacy and narrativity worked as we expected. Therefore, their main effects on perceived closeness and social attraction can still be tested by ANOVA.

3.2.3. Effects of disclosure intimacy and narrativity on closeness and social attraction

Two-way ANOVAs were applied to examine the main effects of disclosure intimacy and narrativity on perceived closeness (one-item closeness and propinquity) and social attraction.

For the one-item measure of closeness, the result of two-way ANOVA revealed a significant interaction effect between the intimacy level and the narrativity level, F(1, 131) = 6.69, p = 0.011, ηp2 = 0.048. Under the condition of low-narrativity, participants in the high-intimacy group (M = 4.14, SD = 1.87) reported a higher level of perceived closeness to the target discloser than those in the low-intimacy group (M = 2.50, SD = 1.38), t (65) = 3.98, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.814; but under the condition of high-narrativity, there was not a significant difference among high-intimacy (M = 3.88, SD = 1.79) and low-intimacy (M = 3.79, SD = 1.79) groups. Under the condition of low-intimacy, participants in the high-narrativity group (M = 3.79, SD = 1.79) reported a higher level of perceived closeness than those in the low-narrativity group (M = 2.50, SD = 1.38), t (62) = 3.21, p = 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.993; but under the condition of high-intimacy, no significant difference among high-narrativity (M = 4.14, SD = 1.87) and low-narrativity (M = 3.88, SD = 1.79) groups was found. As expected, there was a positive main effect of intimacy on closeness, F(1, 131) = 8.31, p = 0.005, ηp2 = 0.059. Interestingly, when we dropped the cases in which participants perceived the target posts as inappropriate (<4), the positive main effect of disclosure intimacy on perceived closeness was stronger, F(1, 95) = 13.92, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.128. These results supported H2a and H3a partially, because we did not expect an interaction effect to be significant.

For the propinquity measure, the result of two-way ANOVA yielded only a weak interaction effect, F(1, 135) = 9.82, p = 0.043, ηp2 = 0.030. The pattern was similar to the one item measure of closeness: Under the condition of low-narrativity, participants in the high-intimacy group (M = 3.81, SD = 1.60) reported a higher level of propinquity toward the target discloser than those in the low-intimacy group (M = 3.03, SD = 1.51), t (68) = 2.08, p = 0.021, Cohen’s d = 0.498. But no significant group difference was found among high-intimacy (M = 3.62, SD = 1.60) and low-intimacy (M = 3.91, SD = 1.41) groups under the condition of high-narrativity. Under the condition of low-intimacy, participants in the high-narrativity group (M = 3.91, SD = 1.40) reported a higher level of perceived closeness than those in the low-narrativity group (M = 3.03, SD = 1.51), t (65) = 2.47, p = 0.008, Cohen’s d = 0.604.

For social attraction, the results of two-way ANOVA showed a negative main effect of disclosure intimacy, F(1, 135) = 20.29, p = 0.001, ηp2 = 0.076. Note that when we dropped the cases in which participants perceived the target posts as inappropriate (<4), the negative main effect of disclosure intimacy on social attraction disappeared, F(1, 98) = 2.74, p = 0.101, ηp2 = 0.027. Anyway, H2b was not supported. No further significant effect of narrativity was observed; therefore H3b was also not supported.

3.3. Discussion

Utilizing an experimental design, Study 1 showed that it is possible to develop a feeling of familiarity and a relatively higher feeling of closeness toward a discloser after browsing his/her posts that were embedded in a stream of other’s updates. A higher amount of self-disclosure is beneficial for creating a feeling of familiarity and closeness.

The role of disclosure intimacy and narrativity were complex: for closeness, we found an interaction effect, indicating that one factor, either intimacy or narrativity, was sufficient to elicit a feeling of closeness. In addition, disclosure intimacy had a positive main effect on the one-item measure of closeness but had a negative effect on social attraction. The correlational statistics in Table 4 also indicated that the correlation between the perceived appropriateness and social attraction was higher than the correlation between perceived appropriateness and closeness. However, when we dropped the cases in which participants rated the target posts as inappropriate (<4), the positive effect of disclosure intimacy on closeness turned stronger, and the negative main effect of disclosure intimacy on social attraction disappeared. These results provided evidence for the important role of perceived appropriateness, especially when it comes to social attraction. Intimate public self-disclosure is thus a double-edged sword: it may increase a feeling of closeness, but it may also decrease social attraction when it is perceived as inappropriate.

However, there are some limitations: first, the sample size was not as large as we aimed for since it was difficult to get enough participants to a lab study during that time period. Second, the results were not exactly the same between the two measures of closeness (the one-item question and the propinquity scale). Third, the interaction effects of closeness between narrative disclosure and intimate disclosure were unexpected. Therefore, it is important to replicate this study with a larger sample size.

4. Study 2

4.1. Methods

4.1.1. Procedure

Study 2 was an online study in order to collect a larger and more heterogeneous sample of participants. The design of study 2, including measures and the sequence of measures, was similar to the Study 1. The reliability of scales can be found in Appendix B. We were concerned that participants might be less devoted compared to the participants in a lab study. Therefore, the stimuli were displayed a second time after the closeness and familiarity measures. Participants can then have a second chance to look at the stimuli if they paid less attention to it the first time.

4.1.2. Sample

Based on the Study 1, we intended to recruit at least 400 participants for Study 2. We recruited participants online, including sending invitation emails to several German university email lists and posting the questionnaire links on Facebook and some forums. Participants who completed this online study were entered into a raffle to receive a 10 euro Amazon voucher, the chance of winning was one out of each five participants.

Four hundred and sixty-one participants completed the online questionnaire. Similar to the selection criteria in Study 1, participants who spent less than 30 s in reading each stimulus were dropped. This resulted in a final sample of 433 participants (161 males; Mage = 25.82 years; SD = 6.38 years).

4.2. Results

4.2.1. The effects of disclosure frequency on familiarity and closeness

Table 5 depicts the descriptive results for the degrees of familiarity with five existing and five new profile owners. Among 433 participants, 39 participants (9.0%) reported “do not remember” when seeing the target profile owner, whereas, for each distractor’s profile, at least 292 participants (>67.4%) correctly recognized that this distractor was not shown before. The level of familiarity with the target discloser (M = 4.61, SD = 1.79) was already higher than the level of familiarity with the third discloser who posted three times (M = 3.84, SD = 1.70), t(317) = 7.69, p < 0.001, supporting H1 (see more information in Table 5). These results were similar to that in Study 1, but the error rate was higher compared to Study 1, which indicates that the online study has more random noises.

Table 5.

Results for familiarity of profile owners in Study 2 (n = 433).

| Description of the profile owner (No. of posts in shown stimuli) | No. of participants clicked “do not remember” | Mean of familiarity | SD of familiarity | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target discloser (5) | 39 | 4.52a | 1.81 | 1 | 7 |

| Other discloser (5) | 36 | 4.53a | 1.73 | 1 | 7 |

| Other discloser (3) | 92 | 3.87b | 1.72 | 1 | 7 |

| Other discloser (1) | 145 | 3.34c | 1.88 | 1 | 7 |

| Other discloser (1) | 170 | 2.86d | 1.56 | 1 | 7 |

| Non-discloser (0) | 314 | 2.40 | 1.53 | 1 | 7 |

| Non-discloser (0) | 297 | 2.57 | 1.53 | 1 | 7 |

| Non-discloser (0) | 293 | 2.52 | 1.42 | 1 | 7 |

| Non-discloser (0) | 338 | 2.11 | 1.35 | 1 | 6.1 |

| Non-discloser (0) | 342 | 2.03 | 1.33 | 1 | 5.7 |

Note: The number in brackets stands for the total amount of posts by that discloser in each stimulus. For the first five disclosers, different superscript letters indicate statistically significant group differences (p < 0.05).

Similar to the results in Study 1, participants in Study 2 also indicated that they felt relatively closer to disclosers who disclose more frequently (see results in Table 6). The target discloser who posted five times (M = 3.42, SD = 1.80) was perceived as emotionally closer compared to the discloser who posted three times (M = 3.14, SD = 1.61), t(337) = 2.65, p = 0.004, who was in turn perceived as emotionally closer than the two disclosers who posted less frequently.

Table 6.

Results for closeness of profile owners in Study 2 (n = 433).

| Description of the profile owner (No. of posts in shown stimuli) | No. of participants clicked “no impression” | Mean of closeness | SD of closeness | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target discloser (5) | 35 | 3.39a | 1.78 | 1 | 7 |

| Other discloser (5) | 32 | 3.47a | 1.74 | 1 | 7 |

| Other discloser (3) | 77 | 3.14b | 1.62 | 1 | 7 |

| Other discloser (1) | 113 | 2.62c | 1.71 | 1 | 7 |

| Other discloser (1) | 143 | 2.23d | 1.39 | 1 | 7 |

Note: The number in brackets stands for the total amount of posts by that discloser in each stimulus. Different superscript letters indicate statistically significant group differences (p < 0.05).

4.2.2. Manipulation check

The descriptive results and correlation statistics can be found in Table 3, Table 4 respectively. A two-way ANOVA for perceived intimacy indicated a significant main effect for both manipulated level of intimacy, F(1, 429) = 56.53, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.116, and manipulated level of narrativity, F(1, 429) = 11.89, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.027, and no significant interaction effect was observed here. A two-way ANOVA for perceived coherence showed a significant main effect of manipulated narrativity, F(1, 429) = 310.61, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.420, and there were no significant main effect of manipulated intimacy and interaction effect.

As expected, the results of manipulation check showed that participants in the high-intimacy condition perceived the target posts as more intimate (M = 5.28, SD = 1.26) than that in the low-intimacy condition (M = 4.38, SD = 1.25), t(431) = 7.36, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.708; and participants in the high-narrativity condition perceived the target posts as more coherent (M = 5.98, SD = 1.12) than that in the low-narrativity condition (M = 3.79, SD = 1.46), t(431) = 17.63, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 1.687. Unfortunately, participants in the high-narrativity condition also perceived the target posts as slightly more intimate (M = 5.02, SD = 1.28) than participants in the low-narrativity condition (M = 4.62, SD = 1.37), t(431) = 3.10, p = 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.298.

Another two-way ANOVA showed that perceived appropriateness also differed across conditions: participants in the high-intimacy condition (M = 4.44, SD = 1.17) perceived the target posts as less appropriate than that in the low-intimacy condition (M = 4.96, SD = 1.16), F(1, 429) = 21.62, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.048; participants in the high-narrativity condition (M = 4.83, SD = 1.19) perceived the target posts as more appropriate than that in the low-narrativity condition (M = 4.55, SD = 1.17), F(1, 429) = 6.21, p = 0.013, ηp2 = 0.014. However, values were significantly above 4 in all conditions, indicating that in general the posts were perceived as appropriate.

We will nevertheless additionally run some exploratory linear regressions due to the confounded nature of the data after reporting the ANOVA results for closeness and social attraction.

4.2.3. Effects of disclosure intimacy and narrativity on closeness and social attraction

For the two measures of closeness, the normality assumptions were not met, and for social attraction, the assumption of homogeneity of variance was not met. Therefore, bootstrapping strategies with 5000 repetitions were used here: two-way ANOVAs (manipulated intimacy × manipulated narrativity) were conducted for the three measures of closeness and social attraction.

For both, the one-item measure of closeness and propinquity, the 95% confidence intervals for main effects and interaction effects contained zero. Therefore, H2a and H3a were not supported. However, there were marginal positive effects of manipulated narrativity on closeness [95% CI: −0.02–0.93; 90% CI: 0.05–0.86] and propinquity [95% CI: −0.01–0.75; 90% CI: 0.05–0.87].

For social attraction, the 95% confidence interval for manipulated intimacy contained zero [−0.59–0.13], but manipulated narrativity was above zero [0.08–0.73]. That means participants in the high-narrativity condition (M = 4.61, SD = 1.29) rated the target discloser as more socially attractive than participants in the low-narrativity condition (M = 4.25, SD = 1.32), t(431) = 2.80, p = 0.003. But the effect of manipulated narrativity on social attraction was no longer significant [95% CI: −0.11–0.56] after we excluded the cases in which target posts were perceived as inappropriate (<4). In Study 2, H2b was rejected, and H3b was partially supported.

4.2.4. Exploratory results: important roles of appropriateness and entertainment value

Because the manipulated narrativity changed the level of perceived intimacy in Study 2, it is unclear whether the narrativity effect is (also) due to intimacy. Hence, measured values of perceived intimacy and narrativity should be used for data analysis. In addition, we later realized that the manipulation of narrativity also changed the level of perceived entertainment value (in addition to perceived appropriateness). Therefore, stepwise regressions were used: For each dependent variable, the perceived intimacy and coherence were first added into the linear regression model (step 1), and then the potentially confounding/mediating variables such as perceived appropriateness and entertainment value were added as predictors (step 2). The assumption of independent errors was not always met for all linear regressions; hence we used bootstrapping strategies with 5000 repetitions and 95% confidence intervals. The results can be found in Table 7 (for Study 1) and Table 8 (for Study 2).

Table 7.

Statistics for bootstrapped linear regression with 5000 repetitions in Study 1 (Unstandardized coefficients followed with 95% confidence intervals).

| Predictors∖DVs | Closeness | Closeness | Propinquity | Propinquity | Attraction | Attraction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived intimacy | 0.286∗ [0.02–0.05] | 0.247 [−0.05–0.54] | 0.215 [−0.02–0.45] | 0.216 [−0.03–0.47] | −0.209 [−0.45–0.03] | −0.171 [−0.37–0.03] |

| Perceived coherence | 0.153 [−0.04–0.35] | −0.028 [−0.23–0.18] | 0.163∗ [0.01–0.32] | −0.012 [−0.17–0.15] | 0.224∗ [0.08–0.37] | 0.035 [−0.10–0.17] |

| Perceived appropriateness | 0.204 [−0.06–0.47] | 0.278∗ [0.03–0.53] | 0.375∗ [0.17–0.57] | |||

| Perceived entertainment value | 0.376∗ [0.17–0.59] | 0.313∗ [0.14–0.49] | 0.287∗ [0.15–0.42] | |||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.04 | 0.17 | 0.04 | 0.21 | 0.08 | 0.32 |

| N | 135 | 135 | 139 | 139 | 139 | 139 |

Note. An asterisk after coefficients means 95% CI does not include zero.

Table 8.

Statistics for bootstrapped linear regression with 5000 repetitions in Study 2 (Unstandardized coefficients followed with 95% confidence intervals).

| Predictors∖DVs | Closeness | Closeness | Propinquity | Propinquity | Attraction | Attraction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived intimacy | 0.088 [−0.04–0.22] | 0.059 [−0.08–0.20] | 0.073 [−0.03–0.18] | 0.055 [−0.06–0.17] | 0.045 [−0.05–0.14] | 0.044 [−0.05–0.14] |

| Perceived coherence | 0.191∗ [0.09–0.29] | 0.018 [−0.08–0.12] | 0.177∗ [0.09–0.26] | −0.006 [−0.09–0.08] | 0.196∗ [0.12–0.27] | 0.001 [−0.07–0.07] |

| Perceived appropriateness | 0.258∗ [0.08–0.43] | 0.268∗ [0.14–0.39] | 0.332∗ [0.21–0.45] | |||

| Perceived entertainment value | 0.315∗ [0.20–0.43] | 0.327∗ [0.25–0.41] | 0.310∗ [0.24–0.38] | |||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.04 | 0.16 | 0.05 | 0.26 | 0.07 | 0.34 |

| N | 398 | 398 | 431 | 431 | 433 | 433 |

Note. An asterisk after coefficients means 95% CI does not include zero.

For the results of step 1, perceived intimacy was only positively associated with the one-item closeness measure in Study 1, and perceived coherence had a positive effect on propinquity and social attraction in both studies. With regard to the results of step 2, the adjusted R2s had been increased largely. The original significant effects of perceived intimacy and coherence were gone. Instead, the perceived appropriateness and entertainment value of target posts significantly predicted propinquity and social attraction.

These results indicated that perceived entertainment value, in addition to perceived appropriateness, played an important mediating role in predicting closeness and social attraction. Across two studies, participants perceived high-narrative disclosure messages as more entertaining, and the entertainment value predicted closeness (propinquity) and social attraction. For the effect of manipulated narrativity on propinquity, the 95% bootstrap confidence interval for the indirect effect of entertainment value, based on 5000 bootstrap samples, was [0.17–0.75] in Study 1, and [0.23–0.51] in Study 2. Similarly, for effect of manipulated narrativity on social attraction, the 95% confidence interval for indirect effect was [0.17–0.64] in Study 1, and [0.22–0.50] in Study 2 (Table 8).

5. General discussion

The current studies utilized a unique design of stimuli that resembles a real-life browsing experience. It aimed to examine whether browsing social media can create a feeling of familiarity and (even) closeness toward strangers who publicly disclose self-information on social media. The results of Study 1 and 2 consistently indicated that it is possible to develop a level of familiarity with a frequent discloser after browsing. Perceived closeness to the target discloser remained relatively low, but the perceived closeness was higher compared to other disclosers who posted less self-information.

More importantly, we aimed to examine the effects of disclosure intimacy and narrativity on perceived closeness and social attraction (when the disclosure was likely to be perceived as appropriate). The manipulation of disclosure intimacy and narrativity worked largely in the direction of our expectation: it was perfect in Study 1; but, in Study 2, even though we used the same stimuli, the manipulation of disclosure narrativity also slightly changed the level of perceived intimacy, and the effect size of manipulated intimacy on perceived intimacy was not as large as that in Study 1.

When it comes to the role of disclosure intimacy, different from previous research (Baruh & Cemalcılar, 2015), no negative relationships between disclosure intimacy and perceived closeness were observed in both studies. In Study 1, there was a positive effect of manipulated disclosure intimacy on perceived closeness (the one-item measure), but a negative effect on social attraction. When we dropped the cases in which participants perceived the disclosure messages as inappropriate in Study 1, the positive effect of manipulated intimacy on perceived closeness turned stronger, and its negative effect on social attraction disappeared. These results partially supported Hypothesis 2. However, no main effects of disclosure intimacy on closeness or social attraction were found in Study 2. This result indicated that, when disclosure messages are mostly appropriate, online participants are less likely, than lab participants, to be influenced by the level of disclosure intimacy.

When it comes to the role of narrativity, we found a conditional positive effect on closeness in Study 1, and a significant positive effect on the social attraction in Study 2. This indicates that participants, when doing the study online, pay more attention to the overall feeling of coherence and narrativity than lab participants. In post-hoc analysis, we also found a mediating effect of perceived entertainment value: narrativity increased the entertainment value, and entertainment value turned out as an important predictor of closeness and social attraction.

As we noticed, the results of two studies slightly differed. This is mainly due to the experiment settings: Study 1 was conducted in lab, but Study 2 was conducted online. Lab participants tend to read the same stimuli more carefully than online participants, hence, in Study 2, the error rate of the familiarity with distractors was higher than that in Study 1 and the manipulation check result of study 2 was not ideal. Even with this drawback, it is practically meaningful to run the same study in online setting, as the online setting is closer to real-life SNS browsing experience than the lab setting.

5.1. Theoretical and practical implications

Much research has been done on the positive effects of public self-disclosure from a discloser’s perspective, such as relieving loneliness (Buechel and Berger, 2012, große Deters and Mehl, 2013, Lee et al., 2013), strengthening relational closeness (Burke & Kraut, 2014), increasing feeling of connectedness (Grieve et al., 2013, Park et al., 2011), and improving subjective well-being (Lee, Lee, & Kwon, 2011). Less attention has been paid to the effects of public self-disclosure from a receiver’s perspective (Edwards et al., 2015, Muscanell et al., 2015), especially regarding the impression formation of the discloser in the zero-acquaintance or get-acquaintance paradigm. Our research contributed to this research gap and provided a better understanding of public self-disclosure on social media and its effect on interpersonal relationships.

The results of two studies contribute to the field of relationship formation on social media. Prior research has mainly focused on the role of intimacy; by examining the role of frequency, intimacy, and narrativity, we offer a more comprehensive understanding of the underlying processes. First, we showed that frequent posting on social media increases the feeling of familiarity and closeness in the zero-acquaintance paradigm. This could also explain the phenomenon of ambient awareness (Levordashka and Utz, 2016, Thompson, 2008, pp. 1–9): merely by reading several posts that are embedded in a stream of other news, social media users can form an impression of the discloser and develop a feeling of closeness (at least when the posts are perceived as appropriate). Second, we examined the role of narrativity that has never been studied in this context. We found a direct or indirect positive effect (via perceived entertainment value) of narrativity on closeness and social attraction. It supported previous research claiming that entertaining posts on social media can bring people closer to each other (Lin et al., 2016, Utz, 2015), and addressed the role of humor in interpersonal relationship formation (Treger, Sprecher, & Erber, 2013).

The results on the effects of disclosure frequency and intimacy also contributed to the debate of familiarity-attraction link. For private conversations, a higher amount of self-disclosure often lead to more closeness (A. Aron et al., 1997), and created familiarity-based liking (Berger and Calabrese, 1975, Zajonc, 1968). Recently, this basic principle has been called into question: Norton et al (Norton et al., 2007) proposed the “less is more” hypothesis that, especially in initial stage of interaction, more information about a person may lead to a higher degree of perceived dissimilarity, and therefore leads to less liking. Our results showed that, for a feeling of closeness, a higher amount of self-disclosure is beneficial; this supports the classic positive effect of self-disclosure on closeness. Nonetheless, intimate self-disclosure, when perceived as inappropriate, seems to be detrimental for perceived social attraction. This is slightly in line with the “less is more” argument.

Therefore, we recommend social media users to be cautious when disclosing intimate self-information publicly on social media, but it would be nice if one can disclose self-information in a narrative way. Practically speaking, frequent posting on social media is good for others to have a feeling of familiarity with oneself, but it does not necessarily lead to social attraction. Especially when such public posts are perceived as inappropriate or lead to negative beliefs, posting may decrease social attraction.

5.2. Limitation and future research

This study has some limitations and follow-up research is needed. First, we purposefully used the design that five posts of the target discloser were embedded in a news stream of fifteen posts. We are not sure how a different number of posts in the stimuli may alter the results. Also, future research may want to use an even more realistic design. For example, posts in the stimuli can pop up one after another in the experiment, to resemble the process of news updating in one’s news stream.

Second, there were some problems with the manipulation: the result of manipulation check in study 2 was not ideal, and we doubted if the manipulation was strong enough. The manipulation checks were measured with the target posts provided on the same page, but closeness and social attraction were not. When participants paid less attention to the stimuli before manipulation check, they were less likely to be influenced by the manipulation when rating closeness and social attraction. Another issue is that disclosure intimacy and appropriateness are naturally correlated. It was not easy to disentangle and manipulate these variables in experiments, though they are distinct concepts in theory.

Third, there were a few problems with regard to the measures of perceived intimacy and one-item closeness. The reliability of the intimacy measure was rather low after translation into German. In addition, even though one-item measure of closeness was popular (Arthur Aron et al., 1992, Jones et al., 1985), it can be an issue (Eder, 2006). In our case, it was more convenient for participants to rate it multi-times for examining H1, and we purposefully added another multi-item measure of propinquity for further examination.

6. Conclusion

In summary, we examined the role of public self-disclosure on interpersonal impression formation by conducting one lab study and another online replication study. Both studies indicated that a higher frequency of self-disclosure on social media is beneficial for others to create a feeling of familiarity with oneself. However, the effects of disclosure intimacy and narrativity on the feeling of closeness and social attraction are somehow influenced by other factors such as perceived appropriateness and entertainment value. On social media, it is usually good (at least does no harm) if one can disclose self-information in a narrative way, as it increases entertainment value; but one has to be cautious when disclosing intimate self-information that might be perceived as inappropriate by others, which can decrease one’s perceived social attraction.

Acknowledgements

The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013)/ERC grant agreement no. 312420.

Biographies

Ruoyun Lin is a Ph.D. student in the social media research group at Leibniz-Institut für Wissensmedien, Germany. Her research interests focus on various psychological effects of social media usage, with special emphasis on self-disclosure, well-being, social comparison, and emotional contagion, etc.

Sonja Utz is a professor of communication via social media at University of Tübingen, Germany. She is the head of the social media research group at Leibniz-Institut für Wissensmedien. Her research focuses on the effects of social media use in interpersonal and professional settings.

Appendix A.

Disclosure information of the target discloser in four conditions

| High-intimacy & Low-narrativity | Low-intimacy & Low-narrativity | High-intimacy & High-narrativity | Low-intimacy & High-narrativity |

|---|---|---|---|

| So much work for school needs to be done. I hope all of these crying and staying up late to do my work for school is gonna be worth it in the end. | I’m staying up late to do my homework … So much work needs to be done! | So much work for school needs to be done before my short trip. I hope all of this staying up late to do my homework is gonna be worth it in the end. | I’m staying up late to do my work for school … So much work needs to be done before my short trip! |

| On my way to Stuttgart airport, I will miss you all! | On my way to Stuttgart airport, it will be a long day! | On my way to Stuttgart airport, I will miss you all! | On my way to Stuttgart airport, it will be a long day! |

| I just noticed that it’s raining – this weather makes me somehow depressed … | I just noticed that it’s raining – I forgot to take the umbrella with me … | Oh, it’s raining in Amsterdam – this weather makes me somehow depressed … | Oh, it’s raining in Amsterdam – I forgot to take the umbrella with me … |

| I guess I just met someone special, had a good time today:) | I just met an interesting person, and had a good time today:) | I guess I met someone special in Amsterdam, had a good time today:) | I met an interesting person in Amsterdam, and had a good time today:) |

| I have so many friends that care about me, lucky me❤! | I have so many friends that are nice and willing to help me. | Just got back from my short trip. I’m so glad that I made it and met so many nice people❤! | Just got back from my short trip. I’m so glad that I met so many interesting people! |

Note: Original stimuli were in German, this is a translated version.

Appendix B.

Measurements

| Items | Scale | |

|---|---|---|

| Perceived coherence (Cronbach’s α = 0.86/0.91)a | Not coherent – coherent | 7-point semantic differential scale |

| Not consistent – consistent | ||

| Not continuously – continuously | ||

| Perceived intimacy (Cronbach’s α = 0.57/0.68)a | Non intimate – intimate | 7-point semantic differential scale |

| Impersonal – personal | ||

| Superficial – in depthb | ||

| Perceived appropriateness (Cronbach’s α = 0.80/0.78)a | Appropriate – inappropriate | 7-point semantic differential scale |

| Suitable to the situation – unsuitable | ||

| Out of place for this context – normal to share in this context | ||

| Improper – proper | ||

| Perceived entertainment value | Boring – entertaining | 7-point semantic differential scale |

| Familiarity | How familiar do you feel to the following profile owners? | 1-7 continuous scale; do not remember |

| Closeness | Compare to other users on Social Net, how close do you feel to the following profile owners? | 1-7 continuous scale; no impression |

| Propinquity (Cronbach’s α = 0.95/0.93)a | Distant – nearby | 7-point semantic differential scale |

| Close – far | ||

| Together – separate | ||

| Proximal – remote | ||

| Disconnected – connected | ||

| Social attraction (Cronbach’s α = 0.86/0.85)a | I think XX could be a friend of minec | 7-point Likert scale |

| It would be difficult to meet and talk with XXc | ||

| XX just wouldn’t fit into my circle of friendsc | ||

| We could never establish a personal friendship with each other. | ||

| I would like to have a friendly chat with XXc |

Note:

“The value before “/” was the Cronbach’s α for Study 1, and the value after “/” was for Study 2.

This item was dropped in both studies because it was not highly correlated with the other two items.

“XX” was replaced by the name of the profile owner accordingly in each item.

References

- Ajzen I. Information processing approaches to interpersonal attraction. In: Duck S., editor. Theory and practice in interpersonal attraction. Academic Press; London: 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Albright L., Kenny D.A., Malloy T.E. Consensus in personality judgments at zero acquaintance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;55(3):387–395. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.55.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman I., Taylor D.A. Holt, Rinehart & Winston; 1973. Social Penetration: The Development of Interpersonal Relationships. [Google Scholar]

- Aron A., Aron E.N., Smollan D. Inclusion of other in the self scale and the structure of interpersonal closeness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;63(4):596–612. [Google Scholar]

- Aron A., Melinat E., Aron E.N., Vallone R.D., Bator R.J. The experimental generation of interpersonal closeness: A procedure and some preliminary findings. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1997 [Google Scholar]

- Baruh L., Cemalcılar Z. Rubbernecking effect of intimate information on Twitter: When getting attention works against interpersonal attraction. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 2015;18(9):506–513. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2015.0099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazarova N.N. Public intimacy: Disclosure interpretation and social judgments on Facebook. Journal of Communication. 2012;62(5):815–832. [Google Scholar]

- Berger C.R., Calabrese R.J. Some explorations in initial interaction and beyond: Toward a developmental theory of interpersonal communication. Human Communication Research. 1975;1(2):99–112. [Google Scholar]

- Bilandzic H. The perception of distance in the cultivation process: A theoretical consideration of the relationship between television content, processing experience, and perceived distance. Communication Theory. 2006;16(3):333–355. [Google Scholar]

- Buechel E., Berger J. 2012. Facebook therapy: Why people share self-relevant content online.http://ssrn.com/abstract=2013148 Retrieved from: [Google Scholar]

- Burke M., Kraut R. Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems. 2014. Growing closer on Facebook: Changes in tie strength through social network site use. [Google Scholar]

- Busselle R., Bilandzic H. Measuring narrative engagement. Media Psychology. 2009;12(4):321–347. [Google Scholar]

- Collins N.L., Miller L.C. Self-disclosure and liking: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;116(3):457–475. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.116.3.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalto C.A., Ajzen I., Kaplan K.J. Self-disclosure and attraction: Effects of intimacy and desirability on beliefs and attitudes. Journal of Research in Personality. 1979;13(2):127–138. [Google Scholar]

- große Deters F., Mehl M.R. Does posting Facebook status updates increase or decrease loneliness? An online social networking experiment. Social Psychological and Personality Science. 2013;4 doi: 10.1177/1948550612469233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eder J. Ways of being close to characters. Film Studies. 2006;8(1):68–80. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards A.P., Gentile C., Edwards C. International communication association. 2015. To tweet or “subtweet”?: Impacts of social networking post valence and directness on interpersonal impressions. [Google Scholar]

- Finkel E.J., Norton M.I., Reis H.T., Ariely D., Caprariello P.A., Eastwick P.W. 2015. When does familiarity promote versus undermine interpersonal attraction? [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garaizar P., Reips U.D. Build your own social network laboratory with Social Lab: A tool for research in social media. Behavior Research Methods. 2014;46(2):430–438. doi: 10.3758/s13428-013-0385-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green M.C., Brock T.C., Kaufman G.F. Understanding media enjoyment: The role of transportation into narrative worlds. Communication Theory. 2004;14(4):311–327. [Google Scholar]

- Grieve R., Indian M., Witteveen K., Tolan G.A., Marrington J. Face-to-face or Facebook: Can social connectedness be derived online? Computers in Human Behavior. 2013;29:604–609. [Google Scholar]

- Jones W.H., Carpenter B.N., Quintana D. Personality and interpersonal predictors of loneliness in two cultures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1985;48(6):1503–1511. [Google Scholar]

- Lee G., Lee J., Kwon S. Use of social-networking sites and subjective well-being: A study in South Korea. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking. 2011;14(3):151–155. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2009.0382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K.-T., Noh M.-J., Koo D.-M. Lonely people are no longer lonely on social networking sites: The mediating role of self-disclosure and social support. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking. 2013;16:413–418. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2012.0553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levordashka A., Utz S. Ambient awareness: From random noise to digital closeness in online social networks. Computers in Human Behavior. 2016;60:147–154. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2016.02.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin R., Levordasha A., Utz S. Ambient intimacy on twitter. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace. 2016;10(1) [Google Scholar]

- McCroskey J.C., McCain T.A. The measurement of interpersonal attraction. Speech Monographs. 1974 [Google Scholar]

- Moreland R.L., Zajonc R.B. Exposure effects in person perception: Familiarity, similarity, and attraction. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 1982;18(5):395–415. [Google Scholar]

- Muscanell N., Ewell P., Wingate V.S. 2015. S/he posted that?! Perceptions of topic appropriateness and reactions to status updates on SNS. [Google Scholar]

- Norton M.I., Frost J.H., Ariely D. Less is more: The lure of ambiguity, or why familiarity breeds contempt. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;92(1):97–105. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton M.I., Frost J.H., Ariely D. Less is often more, but not always: Additional evidence that familiarity breeds contempt and a call for future research. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2013;105(6):921–923. doi: 10.1037/a0034379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park N., Jin B., Annie Jin S.-A. Effects of self-disclosure on relational intimacy in Facebook. Computers in Human Behavior. 2011;27(5):1974–1983. [Google Scholar]

- Rains S.A., Brunner S.R., Oman K. Self-disclosure and new communication technologies: The implications of receiving superficial self-disclosures from friends. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2014:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Sprecher S., Treger S., Wondra J.D. Effects of self-disclosure role on liking, closeness, and other impressions in get-acquainted interactions. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2012:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Sunnafrank M.J. Predicted outcome value during initial interactions: A reformulation of uncertainty reduction theory. Human Communication Research. 1986;13(1):3–33. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson C. New York Times; 2008. Brave new world of digital intimacy.http://individual.utoronto.ca/kreemy/proposal/07.pdf Retrieved from: [Google Scholar]

- Treger S., Sprecher S., Erber R. Laughing and liking: Exploring the interpersonal effects of humor use in initial social interactions. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- Utz S. The function of self-disclosure on social network sites: Not only intimate, but also positive and entertaining self-disclosures increase the feeling of connection. Computers in Human Behavior. 2015;45:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Utz S. Is LinkedIn making you more successful? The informational benefits derived from public social media. New Media & Society. 2016;18(11):2685–2702. [Google Scholar]

- Vorderer P. Communication and the good life: Why and how our discipline should make a difference. Journal of Communication. 2016;66:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Walther J.B., Bazarova N.N. Validation and application of electronic propinquity theory to computer-mediated communication in groups. Communication Research. 2008;35(5):622–645. [Google Scholar]

- Zajonc R.B. Attitudinal effects of mere exposure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1968;9(2):1–27. [Google Scholar]