Abstract

Introduction

Strongyloidiasis can cause hyperinfection or disseminated infection in an immunocompromised host, and is an important factor linked to enterococcal bacteremia and meningitis.

Case reports

We report two cases highlighting the importance of suspecting Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome in patients with enterococcal meningitis.

Conclusion

Our cases highlight the importance of suspecting Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome in cases of community acquired enterococcal bacteremia and meningitis.

Keywords: Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome, enterococcal meningitis, enterococcal bacteremia

Introduction

It is estimated that the global prevalence of strongyloidiasis is between 30 to 100 million.1 Strongyloides stercoralis is an intestinal nematode that is endemic throughout the tropics and subtropics and has a life cycle consisting of free-living and parasitic components.2 Strongyloides stercoralis and Strongyloides fuelleborni can cause strongyloidiasis.3 It can cause autoinfection, chronic persistent infection, hyperinfection (with involvement of the lung and the gastrointestinal system), and disseminated infection involving other organs.2,4 The hyperinfection syndrome causes overwhelming infection in immunocompromised hosts as the parasite begins to replicate without leaving its host, through an accelerated autoinfection cycle.2 Enterococcal meningitis is an uncommon disease which infrequently occurs outside of settings such as neurosurgical intervention or penetrating central nervous system trauma.5 Few cases reports of S. stercoralis hyperinfection and enterococcal meningitis have been reported in the literature.6,7 We hereby report two such cases highlighting that S. stercoralis hyperinfection may be suspected in an enterococcal meningitis when a relevant epidemiological background is present.

Case reports

Case 1

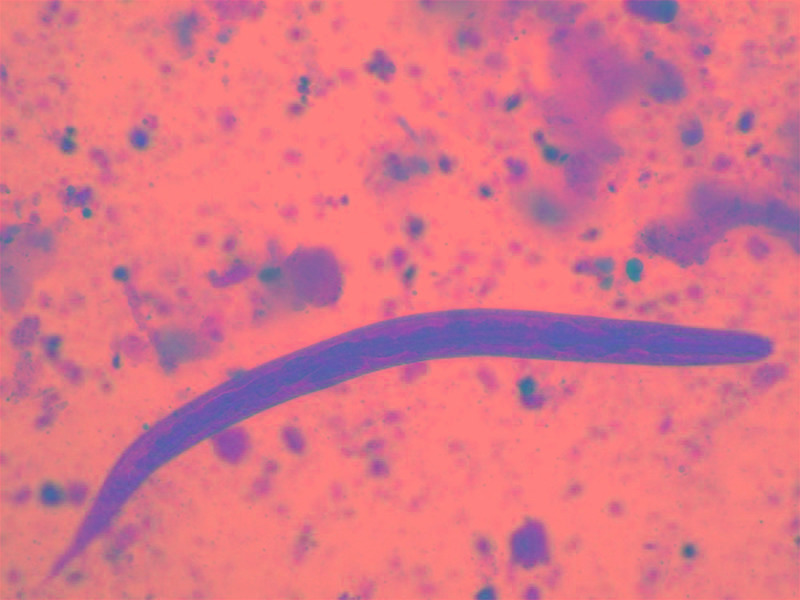

A 65 year-old male presented with complaints of breathlessness and increasing drowsiness for 3 days. He also had self-limited diarrhea for 3 days prior to the start of this illness. He had a history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and was on 20 mg prednisone once a day for frequent exacerbations. He had received cefoperazone-sulbactam and azithromycin for 3 days prior to admission. On examination he was hypotensive (blood pressure 90/60 mmHg), in respiratory distress (respiratory rate 30/min), had a heart rate of 120/min and an axillary temperature of 100 °F (37.8 °C), at a body weight of 60 kg. The patient also presented nuchal rigidity and a Glasgow coma score (GCS) of 6. He was immediately intubated and mechanically ventilated in view of poor GCS and type II respiratory failure. The complete blood count (CBC) revealed slight anemia (hemoglobin 10 g/dL), with neutrophilic leukocytosis (19,000/cmm). The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) picture was consistent with acute bacterial meningitis (leukocyte count of 500/cmm, of which 90% polymorphonuclear cells, a CSF glucose level of 32 mg/dL at a serum glucose level of 150 mg/dL, and CSF proteins at 187 mg/dL). A Gram stain revealed Gram-positive cocci in short chains. On day 4 his blood and CSF cultures subsequently grew penicillin-resistant but vancomycin-susceptible Enterococcus faecalis. Transesophageal echocardiography did not reveal any vegetations. HIV serology was negative and he did not have any underlying immunosuppression apart from steroid use for COPD. Stool examination performed by direct wet mount technique showed filariform larvae of Strongyloides stercoralis (Figure 1). The patient was treated with vancomycin (15 mg/kg IV q8h for 3 days) and ivermectin (200 micrograms/kg for 3 days). He did not improve neurologically and was transferred to a palliative care center at the family’s request. Follow-up information is not available.

Figure 1. The rhabditiform Strongyloides larva is seen in a stool sample of Case 1.

Direct wet mount, magnification 50x.

Case 2

A 20 year-old male presented with abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting for 5 days, which had followed 2 days of high grade fever and drowsiness. The patient had undergone living donor liver transplant 3 years previously and was on tacrolimus (1 mg q12h), mycophenolate mofetil (360 mg q12h) and oral prednisone (7.5 mg q24h). On examination, his blood pressure was 110/80 mmHg, he was breathing at 20 breaths/min, had a heart rate of 110 beats/min and an axillary temperature of 103 °F (39.4 °C) at a body weight of 50 kg. On systemic examination he had epigastric tenderness and nuchal rigidity. A CBC revealed anemia (hemoglobin at 9 gm/dL), neutrophilic leukocytosis (14,000/cmm). HIV serology was negative.

Contrast-enhanced abdominal computed tomography was normal. The patient underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy and subsequent diagnostic laparoscopy, which revealed gastric and duodenal ulcers and a few enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes.

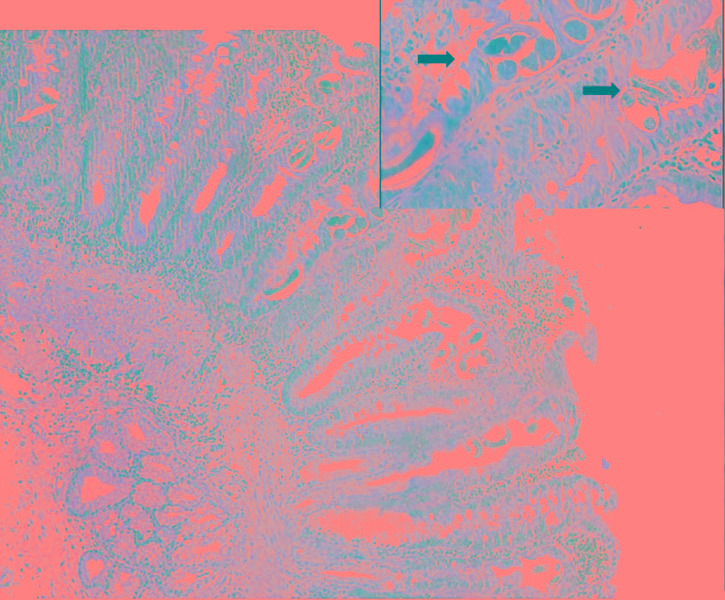

Stool microscopy done by direct wet mount technique showed filariform larvae of S. stercoralis. Histological examination of biopsies of ulcer and lymph node identified parasites with the characteristics of S. stercoralis (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Duodenal biopsy showing inflammatory exudates with magnified view showing eggs and larvae of Strongyloides in the mucosa and mucosal glands (solid arrows).

Hematoxylin and Eosin staining, magnification 40x; inset 100x oil immersion.

The CSF was consistent with acute bacterial meningitis (leukocyte count of 300/cmm with 80% polymorphonuclear cells, a CSF glucose of 22 mg/dL at a serum glucose of 120 mg/dL, and CSF protein of 157 mg/dL). A Gram’s stain showed Gram-positive cocci in pairs and short chains. He was started on vancomycin (15 mg/kg IV q8h) and ceftriaxone (50 mg/kg IV q12h) empirically. On day 3 his CSF and blood culture grew penicillin-resistant but vancomycin-susceptible Enterococcus faecalis, so ceftriaxone was stopped. Ivermectin 200 micrograms/kg was given daily and continued until the stool was cleared of strongyloidal larvae, which took 4 days. He recovered completely and was discharged.

Discussion

Enterococci are normal inhabitants of the large bowel of adults and an uncommon etiology of meningitis, accounting for only approximately 4% of cases,5 usually after neurosurgical procedures. Community acquired enterococcal meningitis is not commonly reported.

Field literature is supportive of a strong association between strongyloidiasis and concurrent immunosuppression caused by immunosuppressive therapy or infection with HTLV-1.8 The most common risk factor for developing severe complicated Strongyloides infection is corticosteroid use.9 Long term requirement of immunosuppressive drugs in solid organ transplant recipients places them at high risk of Strongyloides hyperinfection. Peripheral eosinophilia may not be seen in immunosuppressed patients, making it more difficult to suspect parasitic infection. Eosinophilia was not seen in both of our cases. Gastrointestinal manifestations include abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and ulceration of the small bowel, as seen in our second case. Gram-negative bacteria, Enterococcus and Bacteroides fragilis gain entry into the blood stream through ulcerations in the bowel, by transport on the surface or in the gut of the larvae.10 Meningitis is hypothesized to result from penetration of the blood brain barrier by larvae as a result of disseminated Strongyloides infection11,12 which carry the bacteria with them, or secondary to high grade bacteremia itself, but the exact mechanism has not yet been established.

Strongyloidiasis can be diagnosed by identifying rhabditiform larvae upon microscopic examination of the stool by direct smear, or by culturing on agar plates.13 Repeated stool examination is often necessary for diagnosis of uncomplicated strongyloidiasis, because the sensitivity of a single stool examination is as low as 30%, as small numbers of larvae are shed.2 Hyperinfection however is readily diagnosed by stool examination, which typically identifies filariform larvae in high numbers. Enzyme-linked immunoassays using crude larval antigens have greater sensitivity (> 95%) but low specificity because of their cross-reactivity with other helminthic infections.13 Assays that utilize luciferase immunoprecipitation systems to detect IgG antibodies to a recombinant Strongyloides antigen (NIE) and S. stercoralis immunoreactive antigen (SsIR), have improved sensitivity and specificity.13 Real-time PCR detecting DNA of the parasite can also be done in stool samples, with good specificity and sensitivity.13 All immunosuppressed patients including those with HTLV-1 infection should be screened with serology and, when positive, treated even in the absence of symptoms, or if stool microscopy is negative.13 Choices for the management of uncomplicated strongyloidiasis include oral ivermectin (200 micrograms/kg for 2 days) or tiabendazole (25 mg/kg q12h) or albendazole (400 mg q12h for 10 to 14 days). The drug of choice for complicated strongyloidiasis is ivermectin daily, until larvae are no longer detected in stool, urine or sputum for 2 weeks.13

Both our patients presented with gastrointestinal manifestations of Strongyloides hyperinfection but the symptoms were subtle and overshadowed by the features of acute bacterial meningitis. We looked for and diagnosed Strongyloides hyperinfection after enterococcal bacteremia and meningitis became apparent. Our second patient improved after anti-enterococcal therapy and ivermectin, while for the first patient no follow-up data is available, unfortunately.

Conclusion

Our cases not only highlight the importance of suspecting Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome in cases of community acquired enterococcal bacteremia and meningitis, but also emphasize that immunocompromised individuals should be screened for Strongyloides infection using ELISA, and treated accordingly to prevent hyperinfection syndrome.

Footnotes

Consent: Written consent was obtained from the patients prior to publication.

Authors’ contributions statement: KSS and NB were involved in diagnosis of the case and writing the manuscript. AR and RG supervised patient care and manuscript preparation. MS played a crucial role in microscopic diagnosis of the organisms described in the case report. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest: All authors – none to declare.

References

- 1.Bisoffi Z, Buonfrate D, Montresor A, et al. Strongyloides stercoralis: a plea for action. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:e2214. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grove DI. Human strongyloidiasis. Adv Parasitol. 1996;38:251–309. doi: 10.1016/s0065-308x(08)60036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siddiqui AA, Berk SL. Diagnosis of Strongyloides stercoralis infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:1040–7. doi: 10.1086/322707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vadlamudi RS, Chi DS, Krishnaswamy G. Intestinal strongyloidiasis and hyperinfection syndrome. Clin Mol Allergy. 2006;4:8. doi: 10.1186/1476-7961-4-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arias CA, Murray BE. Enterococcal Infections. In: Longo DL, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, et al., editors. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 19th edition. McGraw Hill Education; 2012. pp. 971–6. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bamias G, Toskas A, Psychogiou M, et al. Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome presenting as enterococcal meningitis in a low-endemicity area. Virulence. 2010;1:468–70. doi: 10.4161/viru.1.5.12703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zeana C, Kubin CJ, Della-Latta P, Hammer SM. Vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium meningitis successfully managed with linezolid: case report and review of the literature. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:477–82. doi: 10.1086/321896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keiser PB, Nutman TB. Strongyloides stercoralis in the immunocompromised population. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17:208–17. doi: 10.1128/CMR.17.1.208-217.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fardet L, Généreau T, Poirot JL, Guidet B, Kettaneh A, Cabane J. Severe strongyloidiasis in corticosteroid-treated patients: case series and literature review. J Infect. 2007;54:18–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ghoshal UC, Ghoshal U, Jain M, et al. Strongyloides stercoralis infestation associated with septicemia due to intestinal transmural migration of bacteria. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17:1331–3. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2002.02750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marcos LA, Terashima A, Dupont HL, Gotuzzo E. Strongyloides hyperinfection syndrome: an emerging global infectious disease. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2008;102:314–8. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ganesh S, Cruz RJ., Jr Strongyloidiasis: a multifaceted disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2011;7:194–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maguire JH. Intestinal nematodes (roundworms) In: Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ, editors. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 8th Edition. Elsevier Saunders; Philadelphia: 2015. pp. 3204–5. [Google Scholar]