Abstract

Purpose

Food service guidelines (FSG) policies can impact millions of daily meals sold or provided to government employees, patrons, and institutionalized persons. This study describes a classification tool to assess FSG policy attributes and uses it to rate FSG policies.

Design

Quantitative content analysis.

Setting

State government facilities in the U.S.

Subjects

50 states and District of Columbia.

Measures

Frequency of FSG policies and percent alignment to tool.

Analysis

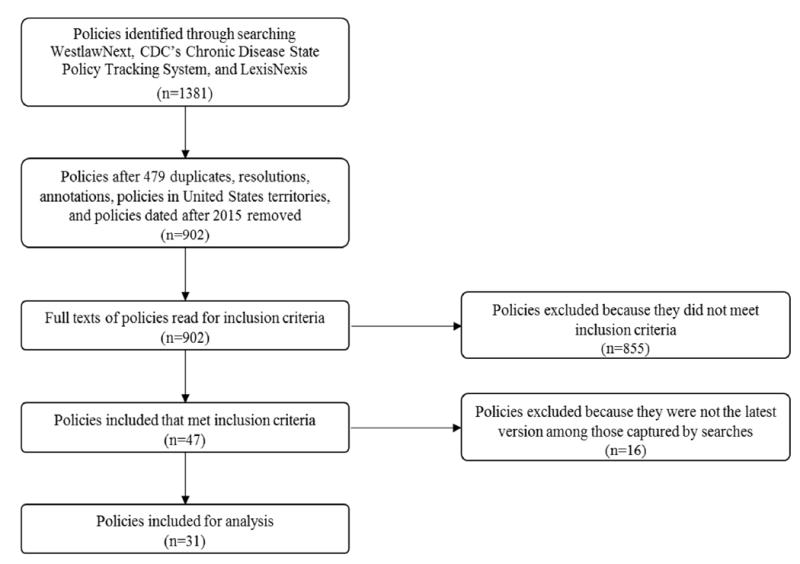

State-level policies were identified using legal research databases to assess bills, statutes, regulations, and executive orders proposed or adopted by December 31, 2014. Full-text reviews were conducted to determine inclusion. Included policies were analyzed to assess attributes related to nutrition, behavioral supports, and implementation guidance.

Results

A total of 31 policies met inclusion criteria; 15 were adopted. Overall alignment ranged from 0% to 86%, and only 10 policies aligned with a majority of FSG policy attributes. Western States had the most FSG policy proposed or adopted (11 policies). The greatest number of FSG policies were proposed or adopted (8 policies) in 2011, followed by the years 2013 and 2014.

Conclusion

FSG policies proposed or adopted through 2014 that intended to improve the food and beverage environment on state government property vary considerably in their content. This analysis offers baseline data on the FSG landscape and information for future FSG policy assessments.

Keywords: Nutrition guidelines, nutrition policy, healthy eating policy, food and beverage environment, healthy food procurement, food service guidelines

PURPOSE

The eating patterns of many people in the United States are not consistent with the 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans.1 Changes in agricultural and food systems in recent decades may have contributed to readily available, inexpensive, energy-dense, large-portioned foods and beverages which may encourage their overconsumption and a sequelae of negative health outcomes.2, 3 Overconsumption of high-calorie foods and beverages, often low in overall nutritional value, contributes to weight gain and obesity, which is a risk factor for several leading causes of death, including heart disease, stroke, diabetes, and certain cancers,4-6 and is at high levels in the US.7 Inexpensive and omnipresent caloric availability is not the only hallmark of obesogenic environments. Diets low in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains; and high in saturated fat, sodium, and added sugars further exacerbate chronic disease risks.1 An analysis of the leading risk factors for death and disability-adjusted life years (DALY) in 2010 showed that dietary composition was the single largest risk factor associated with death and DALY.8 Shifting dietary patterns requires complementary strategies focusing on individual, population, and system approaches to improve dietary choices and food environments.9, 10

The Institute of Medicine and the World Health Organization recommend governments develop policies creating healthier food environments to help prevent and control obesity and diet-related diseases.10, 11 In the United States, policy approaches to improve public health have been successfully implemented in areas such as tobacco, immunization, and seatbelt safety.12-14 In recent years, food-related policies, such as restaurant menu labeling and nutrition standards in early care and education settings, have been utilized as strategies to improve food environments.15, 16 Comprehensive policies targeting food service environments, referred to herein as food service guidelines (FSG) policies, have also been adopted.17, 18 FSG policies delineate food and nutrition standards for the sale and/or provision of foods and beverages, such as the nutrition standards that have been adopted by the United States public school system. They can be implemented in a wide array of settings, in both the public and private sectors (e.g., government worksites and hospitals) and include venues across settings such as cafeterias, vending machines, concession stands, snack shops, meetings, conferences, and other organizational events. Beyond food and nutrition standards, FSG policies may encourage food service approaches that impact the provision and sale of offerings, such as menu labeling and product placement; components that address implementation such as training and compliance; and ecologically and ethically responsible practices that protect humans and the environment, are humane to animals, and treat workers fairly.

Using FSG to improve food environments is also a shared commitment made by the U.S. federal departments on the National Prevention Council chaired by the Surgeon General.19 With nearly three million employees in the federal government, and over 19 million employees working for state or local governments, such guidelines can have an impact on the food environment and potentially impact the health of millions of government employees.20 In addition, the people served by government entities such as institutional members of the armed forces and prisoners under the jurisdiction of federal and state correctional authorities, as well as workers and patrons of parks and recreational facilities, may also benefit from policies supporting a healthier food environment.

Food service guidelines are gaining traction among different levels of government and in other public/private settings as a policy approach to increase the healthfulness of food environments and in turn may improve dietary patterns. In recent years, the development of various science-based FSG guidelines has facilitated FSG implementation.21-25 Despite this growing movement to improve food environments, no systematic analysis of proposed and adopted state FSG policies has been conducted. An assessment of the different policy mechanisms and their content is needed to better understand current FSG policy use and inform future policies’ development and evaluation. Similar studies related to obesity prevention also analyzed both proposed and adopted policies and note that continuing such surveillance is important for assessing progress, identifying effective approaches, and understanding patterns in legislative support.26, 27 The purpose of this paper is to identify proposed and adopted state-level FSG policies, share and utilize a classification tool that was developed to identify and assess FSG policy attributes, and describe key components of policies that can inform stakeholders interested in pursuing the use of FSG and their evaluation.

METHODS

Design

This analysis of state-level FSG policies includes bills, statutes, regulations, and executive orders. A bill is the principal vehicle employed by legislators for introducing proposed laws. A state statute is a state written law. Regulations are rules and administrative codes issued by government agencies that have the force of law because they are adopted under authority granted by statutes. A state executive order is a Governor’s declaration that has the force of law (but limited scope) and typically requires no action by the state legislature. The commercial legal research database, WestlawNext, was used as the primary source for this analysis. A Boolean key word search for “nutrition! /3 (standard or criteri! or guideline)” was conducted to identify proposed and adopted policies from all 50 states and the District of Columbia (from here on referred as “the states”). Data collection began in early 2015 and to ensure we had full years of data, we included policies proposed prior to December 31, 2014. Once identified, a full text review of each policy was completed separately by two trained reviewers (first and second authors), consistent with policy review methods for assessing if a policy met inclusion criteria.28

Sample

To be included in this review, the policy had to specify the development or reference nutritional guidelines that apply to foods and beverages served and/or sold to adult populations in government owned or controlled facilities, including conferences and onsite or offsite events, or had to specify the development of task forces or other committees delegated to develop FSG. Exclusion criteria included policies that dealt with only children and adolescents, food insecurity, and what authors defined as “standards of care”—policies designed to maintain care that is expected of the average, prudent provider, but do not operationalize nutritional guidelines—which were most related to patient and elderly care. For example, we found that many policies have some variation of the following statement, “At least three nutritious meals per day and nutritional snacks, must be provided to each client present at meal times in the detoxification or mental health diversion units.29” Only the latest version of a policy was included for analysis; all earlier versions were excluded from the total policies identified. In cases where similar bills were proposed in the same session, but a different legislator sponsored the bill, those policies were included for analysis because they represent the interests of different constituents. Legislators could have consolidated efforts, but for some reason elected not to and we therefore decided to include such policies because they contribute to the overall policy activity in this area.

Secondary sources were also used to identify additional FSG policies for adult populations. A search of the Centers for Disease and Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Chronic Disease State Policy Tracking System was done using the policy topic, “nutrition standards” to identify additional FSG policies.30 CDC systematically identifies both proposed and adopted state legislation and regulations for this system. This process is documented in the State Legislative and Regulatory Action to Prevent Obesity and Improve Nutrition and Physical Activity methodology.31 At the time of the analysis, policies beyond 2013 that applied to the “nutrition standards” policy topic were not yet publically available in the Chronic Disease State Policy Tracking System. However, contract administrators for the database conducted an independent search using the search string “nutrition standards” and identified relevant FSG policies through August 31, 2014. Due to limitations in identifying executive orders through the aforementioned sources, a search was also conducted using the same Boolean key word search in another commercial legal database, Lexis-Nexis.

Measures

Once all relevant FSG policies were identified, the two reviewers analyzed the text of each policy to assess its content based on the presence or absence of key FSG policy attributes. To facilitate this process, we developed a classification tool to systematically identify key attributes of FSG policies. Our tool was developed using the National Cancer Institute’s Classification of Laws Associated with School Students (CLASS) system, a validated system used to score state-level codified laws for physical education and nutrition in schools based on current public health research and national recommendations and standards for physical education and nutrition in schools.32 We used the CLASS nutrition variables as a foundation and then incorporated components of the Health and Sustainability Guidelines for Federal Concessions and Vending Operations (Health and Sustainability Guidelines). CLASS was selected because it serves as a model for coding school nutrition related policies that are similar in scope to FSG policies. The Health and Sustainability Guidelines were selected because they are derived from the Dietary Guidelines for Americans and are an operational standard for healthy food service. Using these foundational sources, as well as expert opinion and guidance from related areas of policy and practice, we developed a modified classification tool relevant to state government properties that incorporates pertinent policy attributes that comprehensive and effective FSG policies would be expected to include (Appendix).21, 32-35 These attributes are: a.) defined nutrition standards (i.e. specific nutrients or food groups for which standards are specified); b.) behavioral support strategies to encourage healthy eating (e.g. nutrition labeling, pricing, placement, or promotion of healthy foods); and c.) implementation guidance (e.g. assigning responsibility for implementation, addressing compliance, and indicating review/revision of policy over time). We created separate policy abstraction modules encompassing these attributes specific to each policy category—vending, meals, all foods (policy pertains to all foods available on property for sale and/or provision), task force development, and foods served at meetings (healthy meetings). These abstraction modules contain the attributes broken down into specific variables applicable to each policy category. A total of 36 vending variables, 23 meals variables, 23 all foods variables, 24 task force development variables, and 22 healthy meeting variables were developed. As in CLASS, vending variables in our tool are separate for snacks and beverages. We elected to keep this consistency between the tools because we are aware of localities that do not address both and wanted future users to be able to assess such policies, while also giving credit to more comprehensive policies that address both snacks and beverages. The meals category is also based on CLASS, but we included two beverage variables because high calorie beverages contribute to daily caloric intake.36 For instances where a meals policy applied to served populations, the behavioral attributes of pricing, placement, and promotion were not counted against the policy’s score. Unlike CLASS, we created all foods, task force, and healthy meetings categories because they are specific to policies for state government property. The all foods category was based on our meals category, but applied when “all” was used in the policy and reviewers could not discern which venues the policy applied to based on the policy’s text. Abstraction modules also captured basic policy characteristics (e.g. state, year, and policy type) and included an “other” variable for reviewers to code any pertinent information that may have not been captured by the classification tool; this information did not count against a policy’s score. The two reviewers coded each policy for variable presence or absence specific to each of the categories. Upon agreement, the overall proportion of variables present out of the total number possible for that policy type was calculated for each policy. This proportion was further calculated into three sub-scores for nutrition attributes, behavioral support attributes, and implementation guidance attributes. If a policy had a missing variable due to unclear criteria, the variable was considered absent for calculations.

Analysis

Agreement among the two reviewers was assessed using Cohen’s kappa statistic (κ), with agreement assessed as follows: κ= 0.80-1.00 as high, κ= 0.60-0.79 as substantial agreement, κ= 0.40-0.59 as moderate agreement, κ= 0.20-0.39 as fair, and κ= 0.00-0.19 as slight agreement.37 Proportion of agreement was also reported because of limitations.38 In addition to examining policy characteristics and calculating the proportion of nutrition, implementation guidance, and behavioral support attributes present in each policy, we also examined trends by year, United States Census region (West, Midwest, South, and Northeast), and FSG policy category.

RESULTS

The legal database search identified 1381 policies, with 31 policies meeting inclusion criteria (Figure). There were 16 bills, 8 regulations, 4 statutes, and 3 executive orders that met inclusion criteria as FSG policies. In identifying these policies, the two reviewers were in complete agreement k=1, 100% agreement). Prior to reconciliation, reviewer agreement was high for determining the presence and absence of variables (k=0.97, 98.7%). Table 1 presents the policies that met inclusion criteria and characteristics of the policies. A total of 15 FSG policies were adopted during the study period. FSG policies proposed or adopted at the state-level during the study period were limited to 15 states, with California, Massachusetts, Ohio and the District of Columbia having the most FSG-related policies. Most policies applied to the state property setting, which referred to the physical agencies or institutions owned or controlled by the state. Table 2 provides policy trends. The largest number of policies addressed the meals category (10 policies) followed by the eight task force development policies. Western States had the greatest FSG activity, with 11 policies proposed or adopted during the study period. The greatest FSG activity was in 2011, with eight policies followed by the years 2013 and 2014.

Figure.

Flow Diagram for FSG Policy Inclusion

Table 1.

Characteristics of FSG Policies Identified and Percent Alignment to Classification Tool

| Title | Mechanism | State | Year | Status | Category | Setting | Overall Score |

Nutrition Score |

Behavioral Score |

Imple- mentation Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy Arizona Act of 2014 (House Bill 2202) | Bill | AZ | 2014 | Not Adopted | Task Force | State Property | 63% | 82% | 25% | 56% |

| Healthy Arizona Act of 2014 (House Bill 2233) | Bill | AZ | 2014 | Not Adopted | Task Force | State Property | 63% | 82% | 25% | 56% |

| Public Contracts: Healthy and Sustainable food | Bill | CA | 2011 | Not Adopted | Vending, Meals | State Property | 64%, 70% | 86%, 100% | 38%, 25% | 57%, 43% |

| Workplace Wellness Act of 2011 | Bill | DC | 2011 | Not Adopted | Vending | District Property | 22% | 14% | 50% | 14% |

| An Act Relating to Public Cafeterias Concerning Local Purchasing Preferences and the American Heart Association’s Dietary Guidelines | Bill | IA | 2013 | Not Adopted | Task Force | State Property; Public Collegiate Campuses | 79% | 100% | 50% | 67% |

| An Act Relating to Certain Public Cafeterias Concerning Local Purchasing Preferences and Dietary Guidelines | Bill | IA | 2013 | Not Adopted | Task Force | State Property; Public Collegiate Campuses | 71% | 100% | 25% | 56% |

| An Act Relevant to Nutrition in Government Buildings | Bill | MA | 2011 | Not Adopted | All Foods | State Property | 4% | 0% | 0% | 14% |

| An Act Relative to Expanding Access to Healthy Food Choices in Vending Machines on State Property | Bill | MA | 2014 | Not Adopted | Vending | State Property | 72% | 86% | 50% | 71% |

| Food Purchased by State Agencies/Local Governing Authorities for Sponsored Events; Require Healthy Food | Bill | MS | 2012 | Not Adopted | Healthy Meetings | State Property— Sponsored Events | 5% | 0% | 25% | 0% |

| A Bill for an Act Relating to Food Sold in Public Buildings | Bill | OR | 2011 | Not Adopted | All Foods | State Property | 26% | 50% | 0% | 0% |

| A Bill for an Act Relating to Vending Machines Located in Public Buildings | Bill | OR | 2013 | Not Adopted | Task Force | State Property | 8% | 0% | 0% | 22% |

| The Healthy State Employee Act | Bill | RI | 2013 | Not Adopted | Task Force | State Property | 54% | 64% | 25% | 56% |

| Food Standards for Agency Meals (House Bill 1424) | Bill | VA | 2010 | Not Adopted | Task Force | State Property | 8% | 0% | 0% | 22% |

| Food Standards for Agency Meals (House Bill 423) | Bill | VA | 2010 | Not Adopted | Task Force | State Property | 13% | 0% | 0% | 33% |

| An Act Relating to the Establishment of Food Purchasing Policies | Bill | WA | 2011 | Not Adopted | All Foods | State Property | 78% | 100% | 50% | 57% |

| Washington State Agency Food Purchasing Policy | Bill | WA | 2011 | Not Adopted | All Foods | State Property | 48% | 75% | 0% | 29% |

| Minimum Standards for Local Detention Centers | Regulation | CA | 2011 | Adopted | Meals | State— Correction al Facilities | 24% | 42% | 0% | 0% |

| Dietary Allowances | Regulation | MN | 2013 | Adopted | Meals | State— Correction al Facilities | 5% | 8% | 0% | 0% |

| Minimum Standards for Institutions for the Aged or Infirm—Meal Service | Regulation | MS | 2011 | Adopted | Meals | State— Resident Care Facilities | 5% | 8% | 0% | 0% |

| Home-Delivered Meal Services | Regulation | OH | 2010 | Adopted | Meals | State— Communit y-Based Long-Term Care Service Providers | 16% | 25% | 0% | 0% |

| Meal Service | Regulation | OH | 2012 | Adopted | Meals | State— Area Agencies on Aging | 26% | 42% | 0% | 0% |

| Dietary Services; Supervision of Special Diets | Regulation | OH | 2012 | Adopted | Meals | State— Resident Care Facilities | 5% | 8% | 0% | 0% |

| Aging Services Division: Program Standards for Services Funded Under Title III | Regulation | OK | 2009 | Adopted | Meals | State Property-Area Agencies on Aging | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Nutrition and Food Services | Regulation | VT | 2013 | Adopted | Meals | State— Resident Care Facilities | 11% | 17% | 0% | 0% |

| State Property: Vending Machines | Statute | CA | 2007 | Adopted | Vending | State Property | 22% | 43% | 0% | 14% |

| State Property: Vending Machines | Statute | CA | 2014 | Adopted | Vending | State Property | 22% | 43% | 0% | 14% |

| Healthy Food and Beverage Standards for District Government property | Statute | DC | 2014 | Adopted | All Foods | District Property | 65% | 92% | 50% | 29% |

| Nutrition at Department Facilities | Statute | DC | 2014 | Adopted | All Foods | District Property— Parks and Recreation | 48% | 92% | 0% | 0% |

| Establishing Nutrition Standards for Food Purchased and Served by State Agencies | Executive Order | MA | 2009 | Adopted | Meals | State—9 state agencies under the Executive Branch defined as Procurement Level III | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| An Order Promoting Healthy Food and Beverage Options in Executive Branch State Public Properties | Executive Order | TN | 2010 | Adopted | Vending | State Property | 18% | 0% | 75% | 0% |

| Improving the Health and Productivity of State Employees and Access to Healthy Foods in State Facilities | Executive Order | WA | 2013 | Adopted | All Foods | State Property | 86% | 100% | 100% | 50% |

Table 2.

Policy Trends

| Region Policies Adopted/Total Policies | Year Policies Adopted/ Total Policies | Category Policies Adopted/Total Policies | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northeast | 2/5 | 2007 | 1/1 | Vending* | 3/6 |

| South | 5/9 | 2009 | 2/2 | Meals* | 9/10 |

| Midwest | 4/6 | 2010 | 2/4 | All Foods | 3/7 |

| West | 4/11 | 2011 | 2/8 | Task Force | 0/8 |

| 2012 | 2/3 | Healthy Meetings | 0/1 | ||

| 2013 | 3/7 | ||||

| 2014 | 3/6 | ||||

One policy applied to both vending and meal categories.

Table 1 also displays the overall and attribute scores for each policy’s alignment to our classification tool. Of the 31 policies that were proposed or adopted, their overall alignment to our classification tool ranged from 0% to 86%. Among all policies, only 10 met a majority (51% or greater) of our overall criteria and 5 of these 10 policies cited existing guidelines. All of these policies addressing a majority of our overall criteria were proposed or adopted after 2011. Of the 15 adopted policies, only two aligned with a majority of our overall criteria. Of 31 policies, 12 policies included a majority of the nutrition attributes, but only three policies were adopted among them. Within the nutritional component, variables addressed varied by policy category. For example, fruit and vegetables were more likely addressed under the meals category than other variables. Only two policies met a majority of behavioral support attributes and both policies were adopted. Policies were more likely to address providing nutritional information than the pricing, placement, and promotion variables within the behavioral support component. Among all policies, eight policies met a majority of implementation attributes, but none of these were adopted. Within the implementation component, variables related to reviewing standards over time, sustainability, and addressing the proportion of healthier offerings were more likely to be addressed compared to the remainder of implementation variables.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic analysis to identify and describe proposed and adopted FSG policies for foods sold and/or served in state government facilities. The CDC has issued web-based Prevention Status Reports on the status of state-level FSG policies; however, this study identifies and comprehensively assesses key attributes of both proposed and adopted FSG policies over time.39 The FSG policy landscape painted by this analysis shows several important findings. First, state-level FSG policy activity through 2014 was limited to 15 states with only 10 states having adopted policies. Second, among proposed and adopted policies, there is considerable variation among policies on the nutrition standards, behavioral supports, and implementation guidance specified by the policies. Only 10 of 31 policies met a majority (51% or greater) of variables within our classification tool and only two of these policies were adopted, the Washington State executive order and a DC statute. Both of these policies were based on Health and Sustainability Guidelines, which helped increase their overall alignment to our classification tool. While it is difficult to know the political context that may have influenced enactment of these policies, the fact that they were adopted suggests that policymakers are aware of existing guidelines, which may help facilitate adoption and eliminate burdens on policymakers to develop new guidelines. We also found state FSG policies were introduced more frequently during or after 2011, and that all 10 policies that met a majority of our overall criteria were proposed or adopted during or after 2011. It is not known if this is resultant from the release of resources such as the Health and Sustainability Guidelines and Institute of Medicine recommendations.10, 21-23, 34 The Health and Sustainability Guidelines were released in 2011 and other, related guidelines closely followed, suggesting that existing operationalized guidelines may not only help develop more comprehensive policies, but may facilitate FSG policy adoption. Our analysis found that five of the ten policies that met a majority of criteria were based on existing guidelines. While many policies addressed specific nutrition attributes, behavioral support and implementation guidance were less often included in policy language. This may reduce policy effectiveness because previous studies suggest that lack of implementation guidance may undermine the effectiveness of FSG-related policies.33, 40 Inadequate attention to behavioral support and implementation policy components may be a reflection of the novelty of this work, the inherent challenges of enforcement due to the complex nature of food service systems, and that current resources such as the Health and Sustainability Guidelines do not focus on these components. It is to be determined how inclusion of such components in guidance documents will affect the policy-making process.

Several factors may account for the paucity of state FSG policies that comprehensively address nutritional standards, behavioral support, and implementation guidance. Policy change in the United States is incremental in nature. As acceptance and knowledge of policies grows, piecemeal change often follows.41 As more policies are adopted, subsequent policies may be informed by early FSG policies and gradually change policy approaches and standards over time. This was evident in our analysis; several states where policies were not adopted initially tried again and adopted an FSG policy. Moreover, a policy can be modified at multiple points as it moves through the legislative or regulatory process. In some cases, compromises are made to move a policy forward that may remove or weaken sections in order to address concerns regarding perceived negative implications for stakeholders or due to concerns regarding government interference in business or personal choice. In other cases, legislation may be left vague with the intent to create detailed guidelines after the legislation is passed. Although we did not systematically analyze standards developed after legislation was passed, we are aware that some of the policies our analysis identified did result in guidelines being created after the initial policy was passed, such as the executive orders passed by Tennessee and Massachusetts. The resulting guidelines vary greatly in how they address nutritional standards, behavioral support, and implementation guidance.

Currently, many states have regulations for institutional feeding programs for places such as correctional facilities and state hospitals. However, most of these regulations were excluded from our analysis because they did not go beyond standards of care. State regulations are updated routinely and improving such regulations to specify that they meet operationalized guidelines, such as the Health and Sustainability Guidelines, can assist in aligning the foods offered with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans.

In the United States, where a majority of the population has intakes that do not meet the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, substantial efforts are needed to facilitate the consumption of healthier foods and beverages.42, 43 Many parties can play a role in these efforts. State governments encompass extensive systems of employees, service providers, and infrastructure, and their combined actions have the potential to initiate wide-scale public health impact and drive change in regional food systems.44 States can also serve as a model for other organizations for FSG implementation. Given the large population that state governments employ and serve, they can increase the demand for healthy and sustainable foods and potentially shift the production, distribution, and supply of such foods. As product lines become healthier and more sustainable, additional FSG policy implementation may become more feasible and encourage other institutions to pursue such policies. These system changes in turn can complement current FSG policies (e.g. public school food and beverage standards) and help policies span more food environments. This is important for comprehensive social norm change as policies that typically focus on specific populations or settings without considering the broader context may not be sufficient for dietary behavior change.45

As a greater number of state governments work to improve the availability of healthy foods in their facilities through FSG policies, an assessment of their economic and health benefits could help determine their impact. Our research found that current FSG policies varied greatly in type and components addressed. While the diversity of these policies may reflect tailored and innovative approaches to practical concerns within each state, such as regional food distribution, the diversity may have drawbacks. Multiple uncoordinated efforts may duplicate work and differing nutrition guidelines may create confusion among stakeholders as to what constitutes healthy.46 In the future, it may be possible to examine the practicality of government entities moving toward policies that have common nutrition, behavioral support, and implementation attributes and the implications these common practices may have.

The analysis was limited to proposed and adopted state-level legislation, regulation, and executive orders in the United States. Numerous other entities, including Tribal governments, federal agencies, and local governments have implemented FSG policies of various sorts. These policies were not captured by this analysis. Future studies could examine and describe these policies. Numerous policies also exist at the state level for school and early care and education populations, which were outside the scope of our analysis. We did not examine 2015 policies because we began our analysis in early 2015 and did not want policies that may have been introduced later in 2015 to be excluded from analysis. In addition, although the policy characteristics we examined were based on previous policy research32 and current dietary guidance, it is possible we did not consider all policy attributes relevant to an effective policy. Furthermore, because state regulations are continuously updated, it is possible that data sources did not capture the latest version of a regulation. Although we used three different overlapping legal databases to locate FSG policies, it is also possible that some existing FSG policies are not included in the databases we utilized or were not captured by our search methodology.

CONCLUSION

Aligning food environments with dietary recommendations is an important step toward improving dietary intake among Americans. Given the small number of FSG policies that have been adopted in the United States, opportunities to evaluate their effects are limited. This study offers baseline data on both proposed and adopted state-level FSG policies and provides information that can help inform the development of comprehensive FSG policies in the future. As FSG policies evolve over time, stakeholders may use the classification tool developed to assess proposed and adopted FSG policies and track changes over time. Future studies can assess the continued use of FSG policies and their impact on health, the environment, and the economy. Such information is needed to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of these policies and whether there are cost-savings over time. Building on this study’s findings and the methodology developed, stakeholders can begin to systematically evaluate FSG policies and their effects.

SO WHAT? Implications for Health Promotion Practitioners and Researchers.

What is already know on the topic?

Food service guidelines policies can potentially impact the health of millions of government employees, patrons, and institutionalized persons. These policies are increasing in government and private sector settings.

What does this article add?

No systematic analysis of proposed and adopted state FSG policies has been conducted. This article provides a methodology to assess FSG policies to better understand current FSG policy use and inform future policies’ development and evaluation.

What are the implications for health promotion and research?

This article offers baseline data on state-level FSG policies. This can inform FSG policies across sectors, which impact millions of daily meals that can drive food systems change and have wide public health impact. Stakeholders may use the classification tool developed to as.0sess proposed and adopted FSG policies, track changes over time, and systematically evaluate FSG policies and their effects.

Appendix

FSG Classification Tool’s Definitions for Attributes Addressed within Each Category

| Attribute | Definition |

|---|---|

| VENDING MACHINE SNACKS – (applies to any self-service device for public use which, upon insertion of currency dispenses food or beverage) - food/snacks only, excludes beverage | |

| Nutrition | Vending machine (snacks) - applies if policy specifies what criteria were used to specify standards/guidelines other than industry standards |

| Nutrition | Vending machine (snacks) - applies if policy addresses total calories, calorie caps, and/or portion sizes |

| Nutrition | Vending machine (snacks) - applies if policy addresses sugar content |

| Nutrition | Vending machine (snacks) - applies if policy addresses sodium content |

| Nutrition | Vending machine (snacks) - applies if policy addresses saturated fat content |

| Nutrition | Vending machine (snacks) - applies if policy requires 0 grams trans fat in policy |

| Nutrition | Vending machine (snacks) - applies if policy indicates that whole grains be offered |

| Nutrition | Vending machine (snacks) - applies if policy indicates fruits and vegetables be offered (includes variations e.g. fruit snacks, vegetable chips) |

| Behavior | Vending machine (snacks) - applies if policy indicates the posting of calorie information (at a minimum) for each snack be available at point of purchase |

| Behavior | Vending machine (snacks) - applies if policy addresses the pricing of healthier items |

| Behavior | Vending machine (snacks) - applies if policy addresses the promotion of healthier items |

| Behavior | Vending machine (snacks) - applies if policy addresses the placement of healthier items |

| Implementation | Vending machine (snacks) - applies if policy addresses what agency shall supervise the implementation of the policy |

| Implementation | Vending machine (snacks) - applies if policy addresses compliance |

| Implementation | Vending machine (snacks) - applies if policy indicates that training and/or education will be provided to staff and/or vendors |

| Implementation | Vending machine (snacks) - applies if policy indicates a review of the guidelines after an extended period of time will occur to be revised to reflect changes in nutritional science or data |

| Implementation | Vending machine (snacks) - applies if policy addresses sustainability (e.g., sourcing of local foods, waste management, green cleaning practices) |

| Implementation | Vending machine (snacks) - applies if policy requires that a certain percentage of foods offered are healthier |

| Implementation | Vending machine (snacks) - applies if policy addresses that funding will be available to help with implementation, training, enforcement, or similar activities. |

| VENDING MACHING BEVERAGES - excludes non-entrée food/snacks | |

| Nutrition | Vending machine (beverages) - applies if policy addresses what criteria were used to specify standards/guidelines other than industry standards |

| Nutrition | Vending machine (beverages) - applies if policy addresses total calories, calorie caps, and/or portion sizes |

| Nutrition | Vending machine (beverages) - applies if policy addresses the inclusion of water |

| Nutrition | Vending machine (beverages) - applies if policy addresses sugar content |

| Nutrition | Vending machine (beverages) - applies if policy addresses 2%, 1% or fat free milk products and/or provides milk alternatives |

| Nutrition | Vending machine (beverages) - applies if policy provides language to include 100% fruit and/or vegetable juice |

| Behavior | Vending machine (beverages) - applies if policy indicates the posting of calorie information (at a minimum) for each beverage be available at point of purchase |

| Behavior | Vending machine (beverages) - applies if policy addresses the pricing of healthier items |

| Behavior | Vending machine (beverages) - applies if policy addresses the promotion of healthier items |

| Behavior | Vending machine (beverages) - applies if policy addresses the placement of healthier items |

| Implementation | Vending machine (beverages) - applies if policy addresses what agency shall supervise the implementation of the policy |

| Implementation | Vending machine (beverages) - applies if policy addresses compliance |

| Implementation | Vending machine (beverages) - applies if policy indicates that training and/or education will be provided to staff and/or vendors |

| Implementation | Vending machine (beverages) - applies if policy indicates a review of the standards/guidelines will occur after an extended period of time to be revised to reflect changes in nutritional science or data |

| Implementation | Vending machine (beverages) - applies if policy addresses sustainability (e.g., sourcing of local foods, waste management, green cleaning practices) |

| Implementation | Vending machine (beverages) - applies if policy requires that a certain percentage of beverages offered are healthier |

| Implementation | Vending machine (beverages) - applies if policy addresses that funding will be available to help with implementation, training, enforcement, or similar activities. |

| MEAL - applies to cafeterias and/or concessions that serve/sell foods and beverages that standards apply to | |

| Nutrition | Meal - applies if policy addresses what criteria were used to specify standards/guidelines other than industry standards |

| Nutrition | Meal - applies if policy addresses total calories, calorie caps, and/or portion sizes |

| Nutrition | Meal - applies if policy indicates whole grains to be offered |

| Nutrition | Meal - applies if policy indicates that fruits and vegetables be offered |

| Nutrition | Meal - applies if policy addresses sugar content |

| Nutrition | Meal - applies if policy addresses sodium content |

| Nutrition | Meal - applies if policy addresses saturated fat content |

| Nutrition | Meal - applies if policy requires 0 grams trans fat |

| Nutrition | Meal - applies if policy indicates that offered dairy products be 2% or less |

| Nutrition | Meal - applies if policy indicates that offered protein options be lean |

| Nutrition | Meal - applies if policy specifies healthier beverages are made available with meals and/or specifies what beverages are allowable |

| Nutrition | Meal - applies if policy indicates that drinking water be made available during meals or is a preferred beverage option for meals |

| Behavior | Meal - applies if policy indicates the posting of calorie information (at a minimum) for each meal be available at point of purchase/near where the meal is served or on the menu |

| Behavior | Meal - applies if policy addresses the pricing of healthier items |

| Behavior | Meal - applies if policy addresses the promotion of healthier items |

| Behavior | Meal - applies if policy addresses the placement of healthier items |

| Implementation | Meal - applies if policy indicates what agency shall supervise the implementation of the policy |

| Implementation | Meal - applies if policy addresses compliance |

| Implementation | Meal - applies if policy specifies that training and/or education will be provided to staff and/or vendors to ensure compliance |

| Implementation | Meal - applies if policy indicates a review of the standards/guidelines will occur after an extended period of time to be revised to reflect changes in nutritional science or data |

| Implementation | Meal - applies if policy addresses sustainability (e.g., sourcing of local foods, waste management, green cleaning practices) |

| Implementation | Meal - applies if policy requires that a certain percentage of offerings are healthier |

| Implementation | Meal - applies if policy addresses that funding will be available to help with implementation, training, enforcement, or similar activities. |

| ALL - applies to all foods and/or beverages served and sold on government property | |

| Nutrition | All - applies if policy addresses what criteria were used to specify standards/guidelines other than industry standards |

| Nutrition | All - applies if policy addresses total calories, calorie caps, and/or portion sizes |

| Nutrition | All - applies if policy indicates whole grains to be offered |

| Nutrition | All - applies if policy indicates that fruits and vegetables be offered |

| Nutrition | All - applies if policy addresses sugar content |

| Nutrition | All - applies if policy addresses sodium content |

| Nutrition | All - applies if policy addresses saturated fat content |

| Nutrition | All - applies if policy requires 0 grams trans fat |

| Nutrition | All - applies if policy indicates that offered dairy products be 2% or less |

| Nutrition | All - applies if policy indicates that offered protein options be lean |

| Nutrition | All - applies if policy specifies healthier beverages are made available and/or specifies what beverages are allowable |

| Nutrition | All - applies if policy indicates that drinking water be made available |

| Behavior | All - applies if policy indicates the posting of calorie information (at a minimum) be available at point of purchase/near where the meal is served or on the menu |

| Behavior | All - applies if policy addresses the pricing of healthier items |

| Behavior | All - applies if policy addresses the promotion of healthier items |

| Behavior | All - applies if policy addresses the placement of healthier items |

| Implementation | All - applies if policy indicates what agency shall supervise the implementation of the policy |

| Implementation | All - applies if policy addresses compliance |

| Implementation | All - applies if policy specifies that training and/or education will be provided to staff and/or vendors to ensure compliance |

| Implementation | All - applies if policy indicates a review of the standards/guidelines will occur after an extended period of time to be revised to reflect changes in nutritional science or data |

| Implementation | All - applies if policy addresses sustainability (e.g., sourcing of local foods, waste management, green cleaning practices) |

| Implementation | All - applies if policy requires that a certain percentage of offerings are healthier |

| Implementation | All - applies if policy addresses that funding will be available to help with implementation, training, enforcement, or similar activities. |

| TF - Specifies a task force/committee be developed for food standards | |

| Nutrition | TF - applies if policy addresses that the task force will develop nutrition standards based on standards/guidelines other than industry standards |

| Nutrition | TF - applies if policy indicates that the task force will address total calories, calorie caps, and/or portion sizes |

| Nutrition | TF - applies if policy indicates that the task force will address offering of whole grains |

| Nutrition | TF - applies if policy indicates that the task force will address offering of fruits and vegetables |

| Nutrition | TF - applies if policy indicates that the task force will address sodium content |

| Nutrition | TF - applies if policy indicates that the task force will address sugar content |

| Nutrition | TF - applies if policy indicates that the task force will address saturated fat content |

| Nutrition | TF - applies if policy indicates that the task force will require 0 grams trans fat in standards/guidelines developed |

| Nutrition | TF - applies if policy indicates that the task force will address allowable dairy products |

| Nutrition | TF - applies if policy indicates that the task force will address lean protein offerings |

| Nutrition | TF - applies if policy indicates that the task force will address healthier beverage offerings |

| Behavior | TF - applies if policy indicates that the task force will address the provision of nutritional information being made available at point of purchase/near where the meal is served or on the menu |

| Behavior | TF - applies if policy indicates that the task force address the pricing of healthier items |

| Behavior | TF - applies if policy indicates that the task force will address the promotion of healthier items |

| Behavior | TF - applies if policy indicates that the task force addresses placement of healthier items |

| Implementation | TF - applies if policy indicates that the task force indicate what agency shall supervise the implementation of the policy |

| Implementation | TF - applies if policy specifies compliance will be addressed once standards/guidelines are developed |

| Implementation | TF - applies if policy indicates that the task force indicate that training and/or education will be provided to staff and/or vendors |

| Implementation | TF - applies if policy indicates that the task force indicate a review of the standards/guidelines will occur after an extended period of time to be revised to reflect changes in nutritional science or data |

| Implementation | TF - applies if policy indicates that the task force address sustainability (e.g., sourcing of local foods, waste management, green cleaning practices) |

| Implementation | TF - applies if policy indicates that task force will address what percentage of offerings be healthier |

| Implementation | TF - applies if policy indicates the task force address what venues policy will address |

| Implementation | TF - applies if policy indicates that the task force is required to develop standards in specified time frame |

| Implementation | TF - applies if policy indicates what members the task force will include |

| MEET - Applies to all foods and/or beverages on sold/served at meetings, events, and/or similar functions | |

| Nutrition | Meet - applies if policy addresses what criteria were used to specify standards/guidelines other than industry standards |

| Nutrition | Meet - applies if policy addresses total calories, calorie caps, and/or portion sizes |

| Nutrition | Meet - applies if policy indicates whole grains to be offered |

| Nutrition | Meet - applies if policy indicates that fruits and vegetables be offered |

| Nutrition | Meet - applies if policy addresses sugar content |

| Nutrition | Meet - applies if policy addresses sodium content |

| Nutrition | Meet - applies if policy addresses saturated fat content |

| Nutrition | Meet - applies if policy requires 0 grams trans fat |

| Nutrition | Meet - applies if policy indicates that offered dairy products be 2% or less |

| Nutrition | Meet - applies if policy indicates that offered protein options be lean |

| Nutrition | Meet - applies if policy indicates a certain percentage of beverages offered with meals are healthier or specifies what beverages be included |

| Nutrition | Meet - applies if policy indicates that drinking water be made available |

| Behavior | Meet - applies if policy indicates the posting of calorie information (at a minimum) for each meal be available at point of purchase/near where the meal is served or on the menu |

| Behavior | Meet - applies if policy addresses the pricing of healthier items |

| Behavior | Meet - applies if policy addresses the promotion of healthier items |

| Behavior | Meet - applies if policy addresses the placement of healthier items |

| Implementation | Meet - applies if policy indicates what agency shall supervise the implementation of the policy |

| Implementation | Meet - applies if policy addresses compliance |

| Implementation | Meet - applies if policy specifies that training and/or education will be provided to staff and/or vendors to ensure compliance |

| Implementation | Meet - applies if policy indicates a review of the standards/guidelines will occur after an extended period of time to be revised to reflect changes in nutritional science or data |

| Implementation | Meet - applies if policy addresses sustainability (e.g., sourcing of local foods, waste management, green cleaning practices) |

| Implementation | Meet - applies if policy addresses that funding will be available to help with implementation, training, enforcement, or similar activities. |

Footnotes

CDC Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- 1.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture. 2015 –2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. 8. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hill JO, Wyatt HR, Reed GW, Peters JC. Obesity and the environment: where do we go from here? Science. 2003;299(5608):853–855. doi: 10.1126/science.1079857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hill JO, Peters JC. Environmental contributions to the obesity epidemic. Science. 1998;280:1371. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5368.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ledikwe JH, Blanck HM, Kettel Khan L, et al. Dietary energy density is associated with energy intake and weight status in US adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83(6):1362–8. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.6.1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Center for Science in the Public I. [February 10 2015];Why good nutrition is important. http://www.cspinet.org/nutritionpolicy/nutrition_policy.html.

- 6.U.S. Department of Agriculture ERS, Food and Rural Economics Division. America’s Eating Habits: Changes and Consequences. Agriculture Information Bulletin. 1999;750:5–32. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Flegal KM. Prevalence of Obesity Among Adults and Youth: United States 2011-2014. NCHS Data Brief. 2015;219:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.US Burden of Disease Collaborators. The state of US health 1990-2010: burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. JAMA. 2013;310(6):591–608. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.13805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumanyika SK, Obarzanek E, Stettler N, Bell R, Field AE, Fortmann SP, et al. Population- Based Prevention of Obesity: The Need for Comprehensive Promotion of Healthful Eating, Physical Activity, and Energy Balance: A Scientific Statement From American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, Interdisciplinary Committee for Prevention (Formerly the Expert Panel on Population and Prevention Science) Circulation. 2008;118(4):428–464. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.189702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glickman D, Parker L, Sim L, et al., editors. Accelerating progress in obesity prevention solving the weight of the nation. Washington, DC: 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization. Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity, and Health. Geneva: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frieden TR, Mostashari F, Kerker BD, Miller N, Hajat A, Frankel M. Adult Tobacco Use Levels After Intensive Tobacco Control Measures: New York City 2002–2003. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(6):1016–1023. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.058164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacobson v Massachusetts. 197 US 11. 1905 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carpenter CS, Stehr M. The effects of mandatory seatbelt laws on seatbelt use, motor vehicle fatalities, and crash-related injuries among youths. J Health Econ. 2008;27(3):642–662. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. [Accessed June 02 2015];Menu and Vending Machines Labeling Requirements. http://www.fda.gov/Food/IngredientsPackagingLabeling/LabelingNutrition/ucm217762.htm.

- 16.Ritchie LD, Sharma S, Gildengorin G, Yoshida S, Braff-Guajardo E, Crawford P. Policy Improves What Beverages Are Served to Young Children in Child Care. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2015;115(5):724–730. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2014.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kimmons J, Wood M, Villarante JC, Lederer A. Adopting Healthy and Sustainable Food Service Guidelines: Emerging Evidence From Implementation at the United States Federal Government, New York City, Los Angeles County, and Kaiser Permanente. Adv Nutr. 2012;3(5):746–748. doi: 10.3945/an.112.002642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Center for Science in the Public Interest. [Accessed June 02 2015];Examples of policies to increase access to healthier food choices for public places: national, state, and local food and nutrition guidelines. http://cspinet.org/new/pdf/Examples%20of%20National,%20State%20and%20Local%20Food%20Procurement%20Policies.pdf.

- 19.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Accessed June 02 2015];National Prevention Strategy. http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/priorities/prevention/strategy/index.html. [PubMed]

- 20.Willhide RJ. Annual Survey of Public Employment & Payroll Summary Report 2013. U.S. Census Bureau; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 21.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and General Services Administration. Health and Sustainability Guidelines for Federal Concessions and Vending Operations. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 22.U.S. Deartment of Agriculture. [Accessed on June 02 2015];Nutrition Standards for All Foods Sold in Schools. http://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/allfoods_summarychart.pdf.

- 23.American Heart Association. [Accessed June 02.2015];Recommended Nutrition Standards for Procurement of Foods and Beverages Offered in the Workplace. http://www.heart.org/idc/groups/heart-public/@wcm/@adv/documents/downloadable/ucm_320781.pdf.

- 24.Gardner CD, Whitsel LP, Thorndike AN, et al. Food-and-beverage environment and procurement policies for healthier work environments. Nut Rev. 2014;72(6):390–410. doi: 10.1111/nure.12116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kimmons J, Jones S, McPeak HH, Bowden B. Developing and Implementing Health and Sustainability Guidelines for Institutional Food Service. Adv Nutr. 2012;3(3):337–342. doi: 10.3945/an.111.001354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boehmer TK1, Brownson RC, Haire-Joshu D, Dreisinger ML. Patterns of childhood obesity prevention legislation in the United States. Prev Chronic Dis. 2007;4(3):A56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eyler AA, Budd E, Camberos GJ, Yan Y, Brownson RC. State Legislation Related to Increasing Physical Activity 2006-2012. J Phys Act Health. 2016;13(2):207–13. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2015-0010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mersky RM, Dunn DJ. Fundamentals of Legal Research. 8. New York, NY: Foundation Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Idaho Department of Health and Welfare. Rules and Minimum Standards Governing Nonhospital Medically-Monitored Detoxification/Mental Health Diversion Units. 16.07.50. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed February 10 2015];Chronic disease state policy tracking system. http://nccd.cdc.gov/CDPHPPolicySearch//Default.aspx.

- 31.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed February 10 2015];State legislative and regulatory action to prevent obesity and improve nutrtion and physical activity. http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpao/docs/chronic-disease-state-policy-tracking-system-methodology-report-508.pdf.

- 32.Mâsse LC, Frosh MM, Chriqui JF, et al. Development of a School Nutrition–Environment State Policy Classification System (SNESPCS) American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2007;33(4):S277–S291. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mason M, Zaganjor H, Bozlak CT, Lammel-Harmon C, Gomez-Feliciano L, Becker AB. Working With Community Partners to Implement and Evaluate the Chicago Park District’s 100% Healthier Snack Vending Initiative. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:E135. doi: 10.5888/pcd11.140141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Smart Food Choices: How to Implement Food Service Guidelines in Public Facilities. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Dept. of Health and Human Services; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Agron P, Berends V, Ellis K, Gonzalez M. School wellness policies: perceptions, barriers, and needs among school leaders and wellness advocates. J Sch Health. 2010;80(11):527–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2010.00538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Appelhans BM, Bleil ME, Waring ME, et al. Beverages contribute extra calories to meals and daily energy intake in overweight and obese women. Physiol Behav. 2013;122:129–133. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Landis JR, Koch GG. The Measurement of Observer Agreement for Categorical Data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.De Vet HC, Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Hoekstra OS, Knol DL. Clinicians are right not to like Cohen’s kappa. BMJ. 2013;346:f2125. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f2125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed March 1 2016];Prevention Status Reports. http://wwwn.cdc.gov/psr/

- 40.Cradock AL KE, McHugh A, Conley L, Mozaffarian RS, Reiner JF, Gortmaker SL. Evaluating the Impact of the Healthy Beverage Executive Order for City Agencies in Boston, Massachusetts, 2011–2013. Prev Chronic Dis. 2015;12:E147. doi: 10.5888/pcd12.140549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lindblom CE. The Science of “Muddling Through”. Public Administration Review. 1959;19(2):79–88. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krebs-Smith SM, Guenther PM, Subar AF, Kirkpatrick SI, Dodd KW. Americans Do Not Meet Federal Dietary Recommendations. J Nutr. 2010;140(10):1832–1838. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.124826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moore LV, Thompson FE. Adults Meeting Fruit and Vegetable Intake Recommendations —United States 2013. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(26):709–713. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leischow SJ, Best A, Trochim WM, et al. Systems Thinking to Improve the Public’s Health. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2008;35(2, Supplement 1):S196–S203. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Taber DR, Chriqui JF, Vuillaume R, Chaloupka FJ. How State Taxes and Policies Targeting Soda Consumption Modify the Association between School Vending Machines and Student Dietary Behaviors: A Cross-Sectional Analysis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(8):e98249. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sacks G, Rayner M, Stockley L, Scarborough P, Snowdon W, Swinburn B. Applications of nutrient profiling: potential role in diet-related chronic disease prevention and the feasibility of a core nutrient-profiling system. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2011;65(3):298–306. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2010.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]