Abstract

Melatonin is produced in almost all living taxa and is probaly 2–3 billion years old. Its pleiotropic activities are related to its local concentration that is secondary to its local synthesis, delivery from distant sites and metabolic or non-enzymatic consumption. This consumption generates metabolites through indolic, kynuric and cytochrome P450 (CYP) mediated hydroxylations and O-demethylation or non-enzymatic processes, with potentially diverse phenotypic effects. While melatonin acts through receptor dependent and independent mechanism, receptors for melatonin metabolites remain to be identified, while their receptor independent activities are well documented. The human skin with its main cellular components including malignant cells can both produce and rapidly metabolize melatonin in cell type and context dependent fashion. The predominant metabolism in human skin occurs through indolic, CYP-mediated and kynuric pathways with main metabolites represented by 6-hydroxymelatonin, N1-acetyl-N2-formyl-5-methoxykynuramine (AFMK), N1-acetyl-5-methoxykynuramine (AMK), 5-methoxytryptamine, 5-methoxytryptophol and 2-hydroxymelatonin. AFMK, 6-hydroxymelatonin, 2-hydroxymelatonin and probably 4-hydroxymelatonin can potentially be produced in epidermis through UVB-induced non-enzymatic melatonin transformation. The skin metabolites are also the same as those produced in lower organisms and plants indicating phylogenetic conservation across diverse species and adaptation by skin of the primordial defense mechanism. Since melatonin and its metabolites counteract or buffer environmental stresses to maintain its homeostasis through broad-spectrum activities, both melatoninergic and degradative pathways must be precisely regulated, because local concentration of melatonin and its metabolites will decide about the nature of phenotypic regulations. These can be receptor mediated or represent non-receptor regulatory mechanisms.

Keywords: melatonin, AFMK, AMK, metabolism, skin

1. Introduction

Skin and its epidermal compartment in particular, when exposed to hostile environments, must have adopted, during evolution, chemical molecules that would protect it from destructive ultraviolet (UV) wavelengths of solar light and infectious microorganisms (1)(s1, s2). One such molecule is melatonin which is produced in almost all living taxa and may be 2–3 billion years old (2)(s3, s4). Its pleiotropic activity and protective properties against oxidative stress and ultraviolet radiation (UVR) (s5, s6) are well documented. Since melatonin is synthesized (s7–s9) and metabolized in mammalian skin (3)(s10–s12), its cutaneous pleiotropic effects are a consequence of its local concentration, metabolic consumption and generation of metabolites with potentially diverse phenotypic activities acting through receptor dependent and independent mechanisms (4,5)(s13, s14).

2. Metabolism of melatonin: General considerations

2.1. Enzymatic pathways of melatonin metabolism in vertebrates

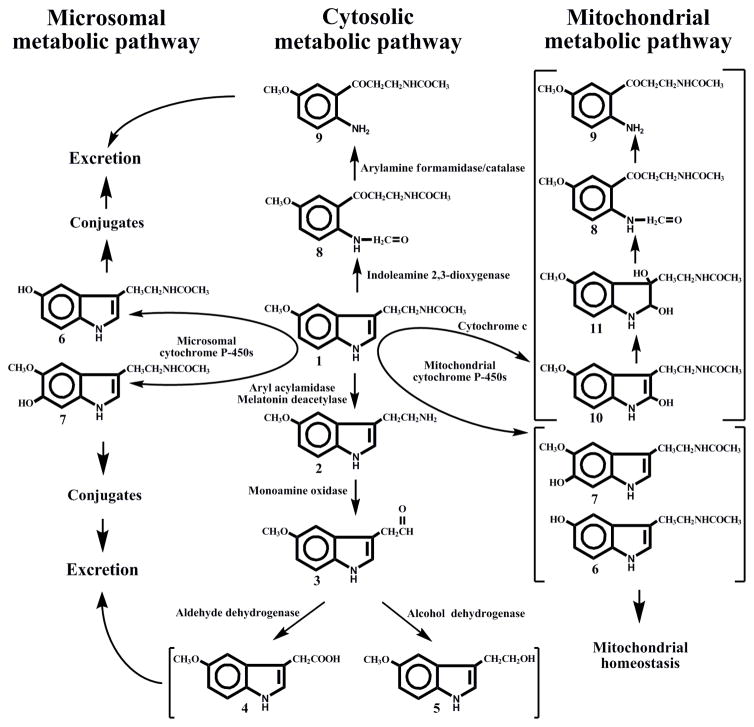

In mammals, melatonin metabolism occurs either directly at the site of production, or in the liver (for circulating melatonin) proceeding through complex pathways associated with cytosol, endoplasmic reticulum (microsomes) and mitochondria (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Overview of enzymatic pathways of melatonin metabolism in vertebrates.

The intermediates of the pathway are identified as follows: (1) melatonin; (2) 5-methoxytryptamine; (3) 5-methoxyindoleacetaldehyde; (4) 5-methoxyindoleacetic acid; (5) 5-methoxytryptophol; (6) N-acetylserotonin; (7) 6-hydroxymelatonin; (8) N1-acetyl-N2-formyl-5-methoxykynuramine; (9) N1-acetyl-5-methoxykynuramine; (10) 2-hydroxymelatonin; (11) 2,3-dihydroxymelatonin

2.1.1. Melatonin deacetylation

In vertebrates melatonin is deacetylated by aryl acylamidase (EC 3.5.1.13) in mammals or melatonin deacetylase in non-mammals to 5-methoxytryptamine, which is deaminated by monoamine oxidase A (EC 1.4.3.4) to 5-methoxyindole acetaldehyde, with its further oxidation by aldehyde dehydrogenase (EC 1.2.1.3) to 5-methoxyindoleacetic acid, an excreted end product, or reduction by alcohol dehydrogenase (EC 1.1.1.1) to 5-methoxytryptophol, a biologically active compound. Aryl acylamidase and monoamine oxidase A are outer mitochondrial membrane-bound proteins, whereas aldehyde dehydrogenase and alcohol dehydrogenase exist as cytosolic and mitochondrial forms. In non-mammalian vertebrates melatonin deacetylation occurs in retina, retinal pigment epithelium, and skin (s15).

In mammals melatonin is deacetylated by liver but not brain aryl acylamidase and it seems that in vivo the quantitative significance of this pathway is minor (s16–s18).

2.1.2. The kynuric pathway

The classic variant of kynuric pathway of melatonin catabolism starts with melatonin pyrrole-ring cleavage to form N1-acetyl-N2-formyl-5-methoxykynuramine (AFMK) in peroxidase-like reaction catalized by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (EC 1.13.11.42), using H2O2 as co-substrate (s19–s21). 2,3-Dioxygenase has a wide tissue distribution in mammals and, subcellularly, has an exclusive cytosolic or perinuclear localization (s22). Melatonin oxidation to AFMK can be also mediated by myeloperoxidase and hemoglobin (s23–s25). Then AFMK is deformylated to N1-acetyl-5-methoxykynuramine (AMK) by arylamine formamidase or by catalase, at least in vitro (s20, s26).

In mitochondria the kynuric pathway of melatonin metabolism is realized through pseudoperoxidase activity of cytochrome c. In the presence of H2O2, cytochrome c can catalyze melatonin conversion into AFMK and its secondary product, AMK, via sequential steps that generate 2-hydroxymelatonin and 2,3-dihydroxymelatonin as intermediates (s27).

2.1.3. Cytochrome P450 mediated metabolism

Circulating melatonin is mainly metabolised by hepatic cytochrome P450s (CYPs) through O-demethylation and 6-hydroxylation. The latter reactions in humans are catalyzed almost entirely by microsomal CYP1A2 (with minimal contributions of CYP2C19 and CYP2C9), generating 6-hydroxymelatonin and N-acetylserotonin (NAS) (28). CYP1A1 and CYP1B1 are probably involved in extrahepatic metabolism of melatonin in intestine and skin (s29).

In rats, melatonin is metabolized not only by microsomal CYPs but also by mitochondrial CYPs (s30). Several CYPs (CYP1A1/2, 2B1/2, 3A1/2 and 2E1) that had been thought to be localized almost exclusively in the microsomes are also found in the mitochondria (Fig. 1) (s31).

Rat CYP1A2 is involved in melatonin 6-hydroxylation and O-demethylation in microsomes and mitochondria (s30). Other CYPs contribute to melatonin metabolism in the mitochondria (CYP3A and CYP2E1), microsomes (CYP2C6) or in both (CYP3A). Mitochondrial CYPs exhibited higher affinity and Vmax for melatonin 6-hydroxylation and O-demethylation as compared to microsomal enzymes, pointing to their functional diversity (s30).

Microsomal 6-hydroxylation and O-demethylation of melatonin is a requirement for its conjugation and release from cells and excretion as glucuronides and sulfates, while 6-hydroxymelatonin and NAS formed in mitochondria can block programmed cell death (s32, s33). Thus, the microsomal pathway is essentially oriented towards the elimination of circulating melatonin, whereas the mitochondrial pathway is adapted to the conversion of melatonin into target compounds that are involved in maintenance of mitochondrial homeostasis. Sub-cellular compartmentalization of melatonin metabolism makes it more targeted and less interfering with each other (Fig. 1).

CYPs-mediated metabolism of melatonin in rodents includes also production of 2-hydroxymelatonin (s30).

2.2. Lessons from lower organisms and plants

To date, melatonin has been identified in about 120 plant species and its concentrations vary widely among species, and this variation depends on environmental factors (s34–s37). In plants, melatonin is largely converted to 2-hydroxymelatonin by the 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase M2H (s38–s40). The evolutionary and functional significance of the high levels of 2-hydroxymelatonin in plants remains to be determined but its lack cyanobacteria (s35) suggests it has a plant specific function.

In dinoflagellates, melatonin is preferably deacetylated to the bioactive metabolite 5-methoxytryptamine (s41–s43), a pathway existing in yeast and mammalian tissues (s44). Another metabolite that can be formed enzymatically and nonenzymatically in vertebrates, dinoflagellates and plants is the AFMK (s19, s45).

Photocatalytic destruction of melatonin may be of particular dermatological interest. For example, in extracts from a dinoflagellate, kelp or slug integuments, AFMK was formed in substantial quantities, already under visible light and in the presence of the hydroxyl radical (s46). AFMK is a recognized radioprotector in human epidermis (s10).

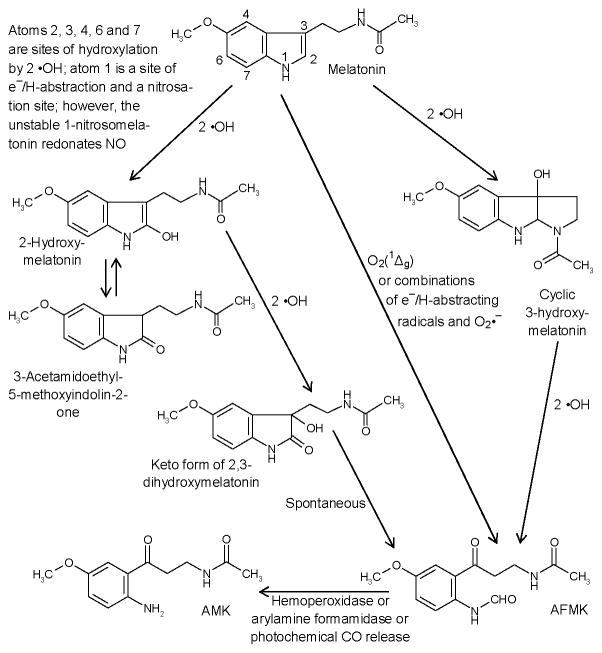

2.4. Non-enzymatic metabolism of melatonin

Nonenzymatic catabolic reactions of melatonin are also relevant, because of its high affinity to free radicals and other reactive intermediates, a property of importance under conditions of oxidative stress, e.g., by local inflammation, under exposure to UV or ionizing radiation. The best known reactions concern the interaction with the hydroxyl radical (•OH) (s47). Within the indolic ring system, the attack can occur at different atoms (s48). Combination with two •OH leads to various hydroxylated metabolites (Fig. 2). Among these, production of 2-hydroxymelatonin, 4-hydroxymelatonin and AFMK, and to lesser degree 6-hydroxymelatonin, can be induced by UVB (λ=280–320 nm) in cell free system (6). 2-Hydroxymelatonin may be further transformed to AFMK under UVB (6), but is also in a tautomeric equilibrium with 3-acetamidoethyl-5-methoxyindolin-2-one (s44). Monooxygenation at ring atom 3 leads to cyclic 3-hydroxymelatonin (s49), which can be converted to AFMK (s19). AFMK is formed by a remarkable spectrum of nonenzymatic reactions by free radicals, various photocatalytic and pseudoenzymatic processes, in addition to enzymatic conversions (s19). The combination of melatonin with singlet oxygen leads directly to AFMK (s50). Various products can be formed from AFMK by free-radical reactions (s51). Among these, AMK is produced by enzymatic or nonenzymatic deformylation (s19), including a photoenergetic CO release from AFMK by exposure to UVC around 254 nm (s52). AMK acts as a scavenger of oxidizing free radicals (s19, s53) and reactive nitrogen species, and it forms stable nitrosation and nitration products (s54, s55). It is also a singlet oxygen quencher more potent than melatonin or histidine (s56).

Figure 2.

Overview of the major nonenzymatic processes of melatonin conversion.

Notably, the reactive oxygen species include O2(1Δg), •OH and O2•−. These can be formed in the skin at elevated rates by UVA and UVB, though in different proportions and by different mechanisms. These mechanisms include inflammatory responses and mitochondrial damage, or combinations thereof. Examples are O2(1Δg) production by endogenous photosensitizers in UVA, from leukocyte-derived OCl− and H2O2, or peroxynitrite formation via UVA-induced decomposition of NO derivatives and enhanced O2•− from mitochondrial dysfunction or leukocytic NADPH oxidase. The main enzymatic conversion of AFMK (N1-acetyl-N2-formyl-5-methoxykynuramine) to AMK (N1-acetyl-5-methoxykynuramine) has been included, since the latter product represents another potent scavenger of O2(1Δg), peroxyl and peroxynitrite-derived radicals, •NO and its redox congeners. For further products formed from AFMK and AMK (see (s5, s19, s44, s51, s54).

3. Metabolism of melatonin in the skin

3.1. Animal skin

Rodent skin contains the machinery necessary to transform L-tryptophan to melatonin, through serotonin and NAS intermediates (3)(s8, s57–s59). Cutaneous melatonin metabolism includes the classical indolic pathway (5), as indicated by production of 5-methoxytryptamine in hamster skin (s8). 6-Hydroxylation and O-demethylation to NAS of melatonin in rodent skin is likely, because of the cutaneous expression of CYP1A1/2, CYP2E1 and CYP3A (s30, s60). In addition, expression of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase and aryl formamidase suggests a presence kynuric pathway of melatonin metabolism in rodent skin (s22, s61). Also there is an extensive metabolism of NAS in rodent skin (s58).

3.2. Human skin

The human skin and skin derived cells can produce and metabolise melatonin (3,5–7)(s7, s9, s11, s12, s62–s65). Thus, CYP1B1 involved in the 6-hydroxylation of melatonin in extrahepatic tissues is one of the few CYP isoforms that are known to be expressed in human skin (s29). Production of NAS in human skin is catalyzed both by AANAT and NAT (3)(s7, s9).

3.2.1. Cultured human skin cells

In all resident skin cells melatonin is rapidly metabolized through both indolic and kynuric pathways (5–8)(s10, s11); however, there is a lack of information on its potential demethylation to NAS (s12). Studies on cultured cells showed that the major product was represented by 6-hydroxymelatonin, with calculated Vmax=16 pmols/hr/106 HaCaT cells and Km=10.2 μM, while metabolism to AFMK was lower with Vmax=0.79 pmols/hr/106 HaCaT cells and Km=18.91 μM (7). In HaCaT keratinocytes we also detected 2-hydroxymelatonin and 4-hydroxymelatonin indicating that these are intermediates in the transformation to AFMK, a process stimulated by UVB (6). Melatonin was also metabolized to AMK in a dose dependent manner with a Vmax=0.091 pmols/hr/106 HaCaT cells and Km=185 μM (s64). AMK production was higher in melanized than in amelanotic melanoma cells (s64).

Melatonin deacetylation as measured by production of 5-methoxytryptamine represents a minor pathway of metabolism (s11). Melatonin metabolism was also cell type dependent, with relative production of 6-hydroxymelatonin and AFMK being the highest in normal epidermal melanocytes, especially from black patients (s11). In normal keratinocytes, dermal fibroblasts and melanoma cells melatonin metabolism was similar. Melanoma cells had high endogenous production of 6-hydroxymelatonin and AFMK (7) as well as of 5-methoxytryptamine and 5-methoxytryptophol (s62), both indicating increased melatoninergic activity coupled to its degradation.

3.2.2. Epidermal melatonin metabolism in vivo

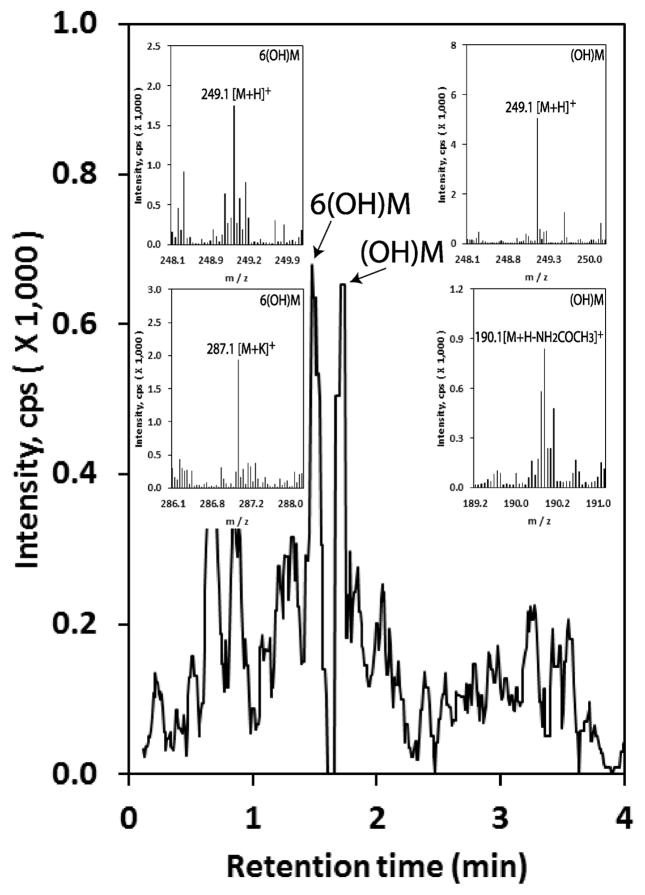

Melatonin and its metabolites including 6-hydroxymelatonin, 5-methoxytryptamine and AFMK (8) and AMK (s64) accumulate in the epidermis, indicating in vivo endogenous melatonin synthesis and metabolism though indolic and/or kynuric pathways. This activity is depended on race, gender and age with highest melatonin levels occurring in young African-Americans, old Caucasian males and Caucasian females (8). AFMK levels are the highest in Caucasians males, while 6-hydromelatonin and 5-methoxytryptamine levels are similar in all groups (8). Additional analysis of human epidermis for mono-hydroxymelatonin by qTOF LC-MS showed an additional hydroxymelatonin metabolite with a retention time different from that of 6-hydroxymelatonin, apparently representing 2-hydroxymelatonin (Fig. 3)

Figure 3.

Hydroxymetabolites of melatonin detected in human epidermis.

Epidermis was extracted with 75% acetonitrile after homogenizing and applied to qTOF LC-MS (EIC) at m/z=249.1 [M+H]+ for hydroxymelatonin as described previously (8). Peak corresponding to 6(OH)M is confirmed by identical retention time as the corresponding 6-hydroxymelatonin standard and additional m/z=287.1 [M+K]+. The additional hydroxymelatonin (OH)M most likely corresponds to 2-hydroxymelatonin, also showing m/z=190.1 [M+H-NH2COCH3]+, because it was detected in HaCaT keratinocytes (7) and has a different retention time from 6-hydroxymelatonin.

Accumulation of AMK in the epidermis (s64) indicated cutaneous metabolism of AFMK to AMK. Its levels were significantly higher in African-Americans than in Caucasians, consistent with data on high production in melanized melanoma cells (s64). The levels did not differ significantly between males and females.

These in vivo data are in agreement with in vitro findings and demonstrate that endogenously produced epidermal melatonin is metabolized through both the indolic and kynuric pathway with the metabolite represented by 6-hydroxymelatonin, 5-methoxytryptamine and final kynuric metabolites represented by AFMK and AMK.

4. Biological and clinical significance of melatonin metabolism in the skin

While melatonin exerts many effects on cell growth regulation and skin tissue homeostasis via melatonin receptors (4)(s66), the strong protective effects of melatonin against UV solar skin damage are mainly mediated through its versatile direct radical scavenging and anti-oxidative enzyme stimulating actions (s67–s70), which also include its metabolites (5)(s71). The effects of the main environmental skin stressor, UV-radiation, are significantly counteracted or modulated by melatonin in the context of a complex intracutaneous melatoninergic antioxidative system (MAS) of the skin, with UV-radiation enhanced melatonin metabolism generating active melatonin metabolites including but not limited to AFMK or AMK (3,5,6)(s71–s73). It is therefore likely that melatonin and its metabolites can serve as potent UV protective substance in vivo. Indeed, it has been shown that topical melatonin can significantly prevent UV erythema formation when applied 15 min before UV exposure (s74).

The clinical and pharmaceutical key challenge for melatonin and its metabolites in the promotion of skin health and disease is to explore the most effective and safe approaches to stimulate the skin’s endogenous MAS (including its capacity to generate melatonin metabolites) or to additionally or synergistically support the endogenous MAS with externally applied melatonin metabolites or analogues for photodamage prevention and repair. For application in clinical dermatology, exogenous melatonin should rather be used topically than orally, since orally administered melatonin appears at rather low levels in the blood due to prominent first-pass degradation in the liver, which limits skin access. Topical administration would circumvent this problem. Also, pharmacodynamically, topical application might be effective because melatonin, with its distinct lipophilic chemical structure, can penetrate and build a depot in the stratum corneum (s70). Therefore, endogenous intracutaneous melatonin production together with its metabolism are expected to represent potent anti-oxidative defense systems against UV-induced solar damage in the skin (3,5,6)(s68, s75). These are in addition to local secosteroidogenic (76–84), pigmentary (s85, s86), cytochrome P450 (s87, s88) and neuroendocrine (s89–s92) systems.

The photo-induced melatonin metabolism leading to the generation of its metabolites in human keratinocytes represents an anti-oxidative cascade which has been proposed in (6). This cascade is able to protect the skin as an important barrier organ against UVR-induced oxidative stress-mediated damaging events on DNA, subcellular, protein and cell morphology level. The UV-induced melatonin metabolites, such as cyclic 3-hydroxymelatonin, AFMK and AMK, are themselves potent antioxidants (s93). Reactive oxygen species occurring during UV irradiation in the skin react directly with melatonin (6). The latter is either autonomously produced in epidermal and/or hair follicle keratinocytes where it engages in intracrine signaling/interactions or released into the extracellular space to regulate auto-, para- or endocrine signaling (1, 3, 5, 6, 9) (s63, s94). The reaction of melatonin with hydroxyl radicals induces the formation of hydroxymelatonin species which can further be metabolized to AFMK or AMK. During this process, hydroxyl radicals are scavenged, and resulting damaging events such as lipid peroxidation, protein oxidation, mitochondrial damage and DNA damage are either indirectly or directly reduced (5, 6)(s67, s71, s73, s95). In addition to its antioxidative properties, melatonin and its metabolite AFMK exhibit pro-differentiation capacities in human epidermal keratinocytes as shown in situ in histocultured human skin, indicating their stimulatory role in building and maintaining the epidermal barrier (7). On the other side, melatonin inhibits proliferation and tyrosinase activity in human epidermal melanocytes (s65) or rodent melanoma cells (s96), while its metabolite AMK has only antiproliferative properties without any effect on melanogenesis (s64). Further numerous pleiotropic effects of melatonin and its metabolites (AFMK/AMK) in human skin have been discussed (3,5–7) (s68, s75). Lastly, because of its high reactivity, AMK can rapidly disappear by oxidation and interaction with reactive nitrogen species. One type of reactions is the interaction of an oxidatively formed AMK intermediate with tyrosyl and tryptophanyl residues, which can lead to covalent protein modification, what may disturb various functions, perhaps also proliferation (s97).

5. Concluding remarks and future perspective

In summary, operation of the indolic and kynuric pathways of melatonin metabolism in human skin is cell-type dependent, stimulated by UVR and oxidative stress, and during which intermediates act via receptor dependent and independent mechanisms. Furthermore, the skin metabolites of both pathways are produced in lower organisms and plants (except 6-hydroxymelatonin) or are generated through non-enzymatic actions indicating phylogenetic conservation across diverse species and adaptation by skin of the primordial physicochemical processes. These are consistent with the original function of melatonin and its kynuric metabolites to serve as protectors against physicochemical (oxidative damage, UVR, chemicals) as well as biological stressors acting at the interphase between internal milieu and environment, e.g., integument/skin.

The melatonin bioactivity would depend also on its local metabolic/degradative pathways generating molecules with lower or higher phenotypic activity depending on cell type and biochemical-physical context. While membrane bound receptors for melatonin are well characterized, which are necessary for precise regulation of phenotypic functions, such receptors for melatonin metabolites remain to be identified. This represents a challenge, since protective activities of melatonin metabolites against the UVB or oxidative stress are similar or even greater than those of melatonin. Thus, combined cutaneous melatoninergic and metabolic systems would act as auto/paracrine protectors against environmentally-induced damage/pathology. It is possible that such protection may even be amplified by local melatonin metabolism.

Thus, precise definition of the mechanisms of action of each intermediate of the melatoninergic/degradative pathway is required. Unfortunately, promiscuity of enzymes metabolizing melatonin for some of which melatonin is only a secondary substrate precludes adequate phenotypic analysis using genetically modified animals that are either knock-out or overexpress enzymes of interest. Similarly we are not aware of studies on gene polymorphisms including defect mutations of melatonin deacetylase, the only enzyme showing some specificity towards melatonin, that would generate changes in phenotype. This represents a challenge for future basic and clinical research, since melatonin and/or its metabolites should be exploited therapeutically or for prevention either as general “skin survival factors” with anti-genotoxic properties or as “guardians” of the genome and cellular integrity with multiple clinical applications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This viewpoint is dedicated to Aaron B. Lerner. The writing was supported by NIH grants 1R01AR056666-01A2 and 1R21AR0666505-01A1 to AS, “German Academy of Natural Scientists Leopoldina” with funds from the “Federal Ministry of Education and Research” Ref-No. BMBF-LPD 9901/8-113 to TWF, the “Aaron B. Lerner”-Scholarship from the Friedrich-Schiller-University Jena, Germany, to TWF and a University of Tennessee Cancer Center Pilot Grant to AS and TWF, and in part by the Else Kröner-Fresenius Foundation, Germany (Else Kröner-Fresenius Stiftung) 2014_A146 to KK. Vast majority of references are labelled s and are listed in the supplemental file per new journal regulations.

References

- 1.Slominski AT, Zmijewski MA, Skobowiat C, et al. Adv Anat Embryol Cell Biol. 2012;212:v, vii, 1–115. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-19683-6_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tan DX, Zheng X, Kong J, et al. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:15858–15890. doi: 10.3390/ijms150915858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Slominski A, Wortsman J, Tobin DJ. FASEB J. 2005;19:176–194. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2079rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Slominski RM, Reiter RJ, Schlabritz-Loutsevitch N, et al. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012;351:152–166. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2012.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Slominski AT, Kleszczynski K, Semak I, et al. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:17705–17732. doi: 10.3390/ijms151017705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fischer TW, Sweatman TW, Semak I, et al. FASEB J. 2006;20:1564–1566. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5227fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim TK, Kleszczynski K, Janjetovic Z, et al. FASEB J. 2013;27:2742–2755. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-224691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim TK, Lin Z, Tidwell WJ, et al. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2015;404:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2014.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Slominski A, Wortsman J. Endocr Rev. 2000;21:457–487. doi: 10.1210/edrv.21.5.0410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.