Abstract

Objective To study the effect of vaccination on mortality before 2 years of age in a developing country.

Design Prospective cohort study.

Setting Rural communities in Burkina Faso.

Participants 9085 children born in the study area between 1985 and 1993.

Main outcome measure Child death rate.

Results Mortality before 2 years of age was lower in children who had been vaccinated: those vaccinated with BCG only had significantly lower mortality (risk ratio for vaccinated v unvaccinated children 0.37, 95% confidence interval 0.29 to 0.48) as did those vaccinated with diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis only (0.24, 0.13 to 0.43). The second dose of diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis was not associated with lower mortality (0.80, 0.58 to 1.12).

Conclusion Vaccination with diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis as well as BCG is associated with better survival of children up to 2 years of age.

Introduction

Vaccination of children, particularly with measles vaccine, has been associated with reduced child mortality.1-4 In Guinea-Bissau, recipients of one dose of diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis vaccine had a higher mortality than those who received none of the childhood vaccines.5 We examined the association between vaccination and child mortality in Burkina Faso.

Materials and methods

We carried out a prospective survey of families living in 26 villages in Burkina Faso. Eight of the villages were in Pissila (1985-95), the remainder in Yako (1986-96). Researchers visited the families every six months, although the average interval in 1993-5 was 12 months. We included all births up to 1993. At each visit the researchers recorded by month for the whole population, births, marriages, migrations (defined as coming in or going out of the study villages), and deaths.6 The mean age of the children was 3.7 months at the first visit, 11.7 months at the second visit, and 20.0 months at the third visit. Data were collected on morbidity and use of health services. The arm circumference of each child was measured as an index of nutritional status.

The health system consisted of eight dispensaries in Yako only. The dispensaries usually had a few drugs, but people often used self medication (traditional or modern), consulted traditional healers, or relied on people who sold modern drugs. Some of the midwives were trained in modern modes of delivery.

Vaccination

Vaccination schedules followed World Health Organization recommendations: BCG at birth; diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis after six weeks—one dose every 28 days (in Yako only two doses); and measles vaccine at nine months (yellow fever was added at one year). Vaccinations undertaken either by a nurse in the dispensaries or by mobile teams, did not comply with the vaccination schedules.

A card was given to the parents at the first vaccination. The researcher collected information from these cards at each visit. When the card was not seen, we assumed that the child had not been vaccinated. When a child died, the mother usually discarded its belongings, including vaccination cards. Similar traditions were observed in Guinea-Bissau.7

Statistical analysis

We used two methods to analyse the association between vaccination and mortality. Firstly, we generated Kaplan-Meier plots: as the date of death was given by month, children were regarded at risk for the whole of that month. Secondly, we determined the relative risk of death by using the Cox proportional hazards model (SAS version 8.2): a value of less than 1 indicated that vaccination was associated with a lower risk of death.

We used Cox regression to study the associations between other factors. Associations with vaccination were analysed by univariate logistic regression. For adjusted analyses, we included all variables associated with mortality and vaccinations (5% level of significance).

Recorded date of vaccination

For our first analysis, we introduced vaccination status as a time dependent covariate: we considered vaccinated children to be unvaccinated until the age of vaccination.8 Follow up was censored at the earliest event among 24 months, death, or out migration. We also censored at measles vaccination, if carried out, to exclude possible beneficial effects on survival.1-3 We checked the proportionality hypothesis assumptions for each model, adding a time dependent covariate (representing the interaction of the original covariate and time). To separate the effects of the diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis vaccine from BCG and to examine any interaction between them, we modelled the first dose of diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis and BCG jointly with two separate age dependent covariates. Follow up began at birth. We also analysed the effect of the second dose of diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis among children who received both vaccines: BCG and the first dose of diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis and follow up began at the last of these two vaccinations. We compared the mortality of children who received BCG and a first dose of diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis with those who received a second dose of diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis.

Vaccination status at the first visit

To avoid bias from unregistered vaccinations, especially when death followed the vaccination and both events occurred between the same two visits, we replicated the method of the Guinea-Bissau study.5 Follow up began from the first visit (before seven months) and ended at the earliest among second visit, age 6 months after first visit, out migration, or death. Children were stratified by age (months) at the first visit: 0 or 1, 2 or 3, and 4-7. We analysed the effects of BCG and diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis vaccines by classifying children into four groups: BCG only; diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis only; BCG and diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis; and neither.

Results

During 1985-96, 9412 births were registered in the Pissila and Yako regions of Burkina Faso. We excluded 204 stillbirths and 123 infants with no recorded month of birth, leaving 9085 infants.

The death rate of these children was high: 90 per thousand in the first year, and 70 per thousand in the second year. By five years, the cumulative rate was 220 per thousand.

Most of the vaccinated children received either BCG (mean age 4.8 months for BCG before 24 months) followed by diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis (mean age 6.3 months), or the vaccines simultaneously. Some children were vaccinated with BCG only, more rarely with diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis only. Before 6 months of age, 45% (4049 of 9085) of the children received BCG or diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis; 21% (1941 of 9085) were vaccinated between six and 24 months (table 1). Overall, 19% (583 of 3050) of the children aged 6 months and 70% (3892 of 5584) of those aged 24 months who had had one dose of diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis, received a second dose (mean age 12.8 months); 39% (1531 of 3892) of them received measles vaccine simultaneously. Measles vaccine (mean age 12.7 months) was usually given with yellow fever vaccine.

Table 1.

Numbers (percentages) of children vaccinated with BCG or diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis by 6 and 24 months of age (or end of observation, if occurred before these ages) and numbers (percentages) of deaths analysed (measles censored)

|

Vaccination status

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Unvaccinated | BCG only | Diptheria, tetanus, and pertussis only | BCG and diptheria, tetanus, and pertussis | Total No |

| Timing of vaccination: | |||||

| Before 6 months | 5036 (55.4) | 999 (11.0) | 263 (2.9) | 2787 (30.7) | 9085 |

| Before 24 months | 3095 (34.1) | 406 (4.5) | 280 (3.1) | 5304 (58.4) | 9085 |

| Time of death: | |||||

| <6 months | 435 (4.8) | 6 (0.1) | 0 | 6 (0.1) | 447 |

| 6-11 months | 264 (2.9) | 28 (0.3) | 5 (0.1) | 76 (0.8) | 373 |

| 12-24 months | 259 (2.9) | 30 (0.3) | 6 (0.1) | 125 (1.4) | 420 |

| Total No of deaths at ≤24 months | 958 (10.5) | 64 (0.7) | 11 (0.1) | 207 (2.3) | 1240 |

All significant associations between mortality or vaccination and covariates were as expected—for example, the presence of a dispensary in the village was associated with reduced mortality and increased the likelihood of vaccination (table 2).

Table 2.

Risk ratios for mortality (6-24 months) and odds ratios for vaccination by selected covariates in children in two regions of Burkina Faso

| Covariate (missing data) | No of deaths | Risk ratio (95% CI) for mortality (6-24 months) | Odds ratio (95% CI) for BCG or diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis v unvaccinated status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boys | 364 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Girls | 351 | 0.93 (0.80 to 1.08) | 0.95 (0.88 to 1.04) |

| Area | |||

| Pissila | 333 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yako* | 382 | 0.72 (0.62 to 0.83) | 2.97 (2.72 to 3.25) |

| Age of mother | |||

| ≥20 | 624 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 15-19 | 91 | 1.22 (0.98 to 1.53) | 0.79 (0.69 to 0.90) |

| Paternal factors | |||

| Age† (n=307) | 695 | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.01) | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.00) |

| No (0 to 4) of wives at birth of child† (n=497) | 683 | 1.15 (1.07 to 1.24) | 1.00 (0.96 to 1.05) |

| Mode of delivery (n=4327) | |||

| Traditional | 189 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Modern | 183 | 1.08 (0.88 to 1.33) | 3.12 (2.77 to 3.51) |

| Dispensary in village | |||

| No | 527 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes* | 188 | 0.78 (0.66 to 0.92) | 2.41 (2.20 to 2.65) |

| Health service use | |||

| Child† (n=1255): | |||

| Rarely | 310 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Sometimes | 176 | 1.01 (0.92 to 1.11) | 1.58 (1.49 to 1.67) |

| Frequently | 130 | 1.02 (0.85 to 1.23) | 2.50 (2.22 to 2.79) |

| Family† (n=55): | |||

| Rarely | 449 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Sometimes | 137 | 0.87 (0.79 to 0.95) | 1.44 (1.37 to 1.52) |

| Frequently | 128 | 0.76 (0.62 to 0.90) | 2.07 (1.88 to 2.31) |

| Problems during first year | |||

| Diarrhoea: | |||

| No | 501 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes* | 214 | 1.37 (1.17 to 1.61) | 1.24 (1.15 to 1.34) |

| Fever: | |||

| No | 503 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 212 | 1.16 (0.98 to 1.36) | 1.54 (1.41 to 1.70) |

| Cough: | |||

| No | 584 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 131 | 1.19 (0.99 to 1.44) | 1.32 (1.18 to 1.48) |

| Malnutrition† (n=4388): | |||

| None | 136 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Mild | 143 | 1.28 (1.11 to 1.47) | 1.06 (0.98 to 1.15) |

| Severe | 73 | 1.64 (1.23 to 2.16) | 1.13 (0.96 to 1.32) |

| Birth season | |||

| Nov to Feb | 491 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Mar to Oct* | 224 | 0.83 (0.71 to 0.97) | 1.64 (1.50 to 1.80) |

| Birth period† | |||

| Pissila, 1986-8; Yako, 1987-9 | 328 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Pissila, 1989-91; Yako, 1990-2 | 254 | 0.82 (0.75 to 0.91) | 1.01 (0.96 to 1.07) |

| Pissila, 1992-3; Yako, 1993-6 | 133 | 0.67 (0.56 to 0.83) | 1.02 (0.92 to 1.14) |

Adjusted.

Quantitative variable.

Vaccination and mortality

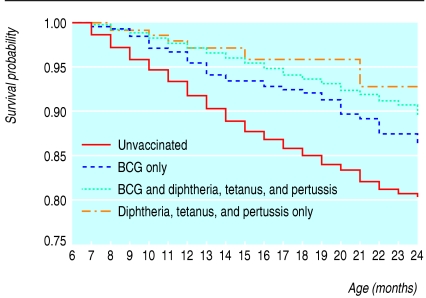

The survival curves for vaccinated children from six to 24 months were significantly different to the survival curve for unvaccinated children (figure).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves of children by vaccination status at 6 months of age

Vaccination with BCG was associated with lower mortality when data were analysed by vaccination status (risk ratio 0.37) and vaccination status recorded at the first visit (risk ratio 0.46). Risk ratios for diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis were similar to BCG (table 3). Adjusted relative risks were also similar (table 3). Results for boys and girls were similar to those for both sexes (table 4). Table 5 shows that the second dose of diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis was not associated with lower mortality.

Table 3.

Non-adjusted and adjusted risk ratios (95% confidence intervals) for mortality for BCG and diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis vaccines analysed by vaccination status before age 2 years and vaccination status at first visit

|

Vaccination status at age <2 years

|

Vaccination status at first visit

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Deaths/person months at risk | Risk ratio (95% CI) for mortality | Deaths/person months at risk | Risk ratio (95% CI) for mortality |

| Non-adjusted: | ||||

| Unvaccinated | 958/72 938 | 1.00 | 281/28 128 | 1.00 |

| BCG | 64/14 238 | 0.37 (0.29 to 0.48) | 29/6262 | 0.46 (0.31 to 0.68) |

| Diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis | 11/3411 | 0.24 (0.13 to 0.43) | 2/1015 | 0.20 (0.05 to 0.79) |

| BCG and diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis | 207/44 515 | 0.33 (0.28 to 0.38) | 33/7385 | 0.44 (0.31 to 0.64) |

| Adjusted*: | ||||

| Unvaccinated | 953/72 410 | 1.00 | 280/27 987 | 1.00 |

| BCG | 63/14 224 | 0.37 (0.29 to 0.48) | 28/6254 | 0.50 (0.34 to 0.75) |

| Diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis | 10/3407 | 0.23 (0.12 to 0.43) | 2/1015 | 0.24 (0.06 to 0.96) |

| BCG and diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis | 206/44 440 | 0.34 (0.29 to 0.40) | 33/7357 | 0.50 (0.35 to 0.73) |

Adjusted for area, dispensary in village, frequent use of health services by family, diarrhoea during first year, and birth season.

Table 4.

Non-adjusted and adjusted risk ratios (95% confidence intervals) for mortality by sex for BCG and diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis vaccines analysed by vaccination status at less than 2 years of age and vaccination status at first visit

|

Vaccination status at age <2 years

|

Vaccination status at first visit

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Deaths/person months at risk | Risk ratio (95% CI) for mortality | Deaths/person months at risk | Risk ratio (95% CI) for mortality |

| Non-adjusted | ||||

| Boys: | ||||

| Unvaccinated | 478/36 659 | 1.00 | 141/13 993 | 1.00 |

| BCG | 29/7369 | 0.33 (0.23 to 0.48) | 12/3244 | 0.36 (0.20 to 0.66) |

| Diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis | 3/1704 | 0.13 (0.04 to 0.41) | 1/515 | 0.19 (0.03 to 1.37) |

| BCG and diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis | 105/22 405 | 0.33 (0.27 to 0.42) | 18/3845 | 0.46 (0.28 to 0.75) |

| Girls: | ||||

| Unvaccinated | 480/36 279 | 1.00 | 140/14 135 | 1.00 |

| BCG | 35/6869 | 0.42 (0.29 to 0.59) | 17/3018 | 0.57 (0.34 to 0.94) |

| Diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis | 8/1707 | 0.33 (0.17 to 0.68) | 1/500 | 0.20 (0.03 to 1.43) |

| BCG and diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis | 102/22 110 | 0.32 (0.26 to 0.40) | 15/3540 | 0.42 (0.25 to 0.72) |

| Adjusted* | ||||

| Boys: | ||||

| Unvaccinated | 475/36 373 | 1.00 | 140/13 923 | 1.00 |

| BCG | 29/7364 | 0.34 (0.23 to 0.49) | 12/3244 | 0.42 (0.23 to 0.77) |

| Diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis | 3/1704 | 0.14 (0.05 to 0.45) | 1/515 | 0.25 (0.03 to 1.83) |

| BCG and diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis | 104/22 362 | 0.35 (0.28 to 0.44) | 18/3823 | 0.54 (0.33 to 0.89) |

| Girls: | ||||

| Unvaccinated | 478/36 037 | 1.00 | 140/14 064 | 1.00 |

| BCG | 34/6860 | 0.41 (0.29 to 0.58) | 16/3010 | 0.58 (0.34 to 0.98) |

| Diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis | 7/1703 | 0.31 (0.15 to 0.66) | 1/500 | 0.22 (0.03 to 1.62) |

| BCG and diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis | 102/22 078 | 0.33 (0.27 to 0.42) | 15/3534 | 0.47 (0.27 to 0.80) |

Adjusted for area, dispensary in village, frequent use of health services by family, diarrhoea during first year, and birth season March to October.

Table 5.

Risk ratios (95% confidence intervals) for mortality for second dose of diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis vaccine among children vaccinated with BCG

|

Non-adjusted

|

Adjusted*

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Timing of diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis vaccine after BCG | Deaths/person months at risk | Risk ratio (95% CI) for mortality | Deaths/person months at risk | Risk ratio (95% CI) for mortality |

| First dose | 149/31 109 | 1.00 | 148/31 104 | 1.00 |

| Second dose | 58/13 266 | 0.80 (0.58 to 1.12) | 58/13 266 | 0.91 (0.64 to 1.28) |

Adjusted for area, dispensary in village, frequent use of health services by family, diarrhoea during first year, and birth season March to October.

Discussion

Vaccination of children in Burkina Faso with BCG and diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis was associated with improved survival before 24 months. These effects remained unchanged when analyses were controlled for potential confounders, and were similar for both sexes.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

The strengths of our study were, firstly, that the vaccination programme was independent of the survey, secondly, that the results were robust, and thirdly, that we studied a relatively large sample, including subgroups of vaccinated and unvaccinated children. Additionally, we found that the associations between covariates and survival, or vaccination, were as expected (see table 2).

Our study had three main weaknesses. Firstly, it was not a controlled trial, for ethical reasons. Although the results did not change when we considered a wide variety of covariates, including the use of the health service, nutritional status, and demographic variables, we cannot exclude the possibility that the results were influenced by unmeasured confounding effects. Secondly, there was a possibility of misclassification of vaccination status, particularly for dead children whose vaccination cards had been destroyed. These cards were generally filed together by the family, so it is unlikely, though not impossible, that some had been lost and the children wrongly considered as unvaccinated. To correct for this, we repeated all analyses by vaccination status recorded at the first visit. Thirdly, vaccines were not given independently. It has been stressed that vaccines were not distributed at random anywhere,9 and this was true of our study. Thus, most vaccinated children received all vaccines whereas others received none. Receipt of BCG and diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis in particular were strongly correlated: about two thirds of the children vaccinated with BCG before 6 months of age also received diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis.

Comparison with other studies

Our findings did not concur with those of a previous study, which found that early vaccination with diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis impairs survival. Both studies were undertaken in areas of high mortality, and both had similar problems with misclassification of vaccination status.

Hypotheses have been formulated concerning the relation between mortality and sex.10 After adjustment for sex the results were similar to those with no adjustment for sex. All analyses carried out separately on boys and girls gave results similar to those for the sexes combined.

To maximise comparability between the two studies, we used similar methods for analysis. We had a group of 175 (19 in Guinea-Bissau) children who received diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis but not BCG before the first visit and 433 children who were vaccinated first with diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis. Our results were robust to the different methods of analysis.

The differences could be related to an earlier age at vaccination in Guinea-Bissau or to differences between the two regions. In Guinea-Bissau, deaths peaked at the end of the rainy season, whereas in Burkina Faso they peaked during the dry, hot season.11 The causes of death and the efficacy of the vaccines should therefore be different. In Senegal, where mortality peaks at the end of the rainy season, diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis vaccine was not associated with mortality.12

Issues for further research

The reduction in mortality associated with vaccination was greater than mortality from specific disease. The reasons for these unspecific effects remain unclear. Studies are needed to confirm whether higher survival is a consequence of vaccination or due to confounding effects.

What is already known on this topic

In developing countries, vaccination with BCG is associated with better survival of children

A study in Guinea-Bissau suggested that diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis vaccine might be associated with lower survival

What this study adds

BCG and diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis vaccines had no adverse effects on mortality in children

A first dose of diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis was associated with better survival

Contributors: All the authors participated in the design of the study, interpretation of data, and revision of the final text. JV did the field research and drafted the paper; he is the guarantor. SP did the statistical analysis. GG participated in the demographic background analysis. EE participated in the statistical analysis. FS suggested this work.

Funding: This study was funded by a field research grant from Unicef and Eau, agriculture, et santé en milieu tropical, and an analysis grant from WHO.

Competing interests: SP has been a consultant statistician for Aventis Pasteur and Aventis Pasteur MSD on pertussis, rotavirus, and herpes zoster. EE has been funded by Aventis to attend a meeting.

Ethical approval: No ethical committee existed in Burkina Faso at the time of the demographic survey and at the start of this analysis of the database. Nevertheless, this study was approved by the Ministry of Health of Burkina Faso.

References

- 1.Hull HF, Williams PJ, Oldfield F. Measles mortality and vaccine efficacity in rural west Africa. Lancet 1983;1: 972-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Koenig MA, Khan MA, Wojtyniak B, Clemens JD, Chakraborty J, Fauveau V. The impact of measles vaccination upon childhood mortality in Matlab, Bandgladesh. Bull WHO 1990;68: 441-7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garenne M, Leroy O, Beau JP, Sene I. Efficacity of measles vaccines after controlling for exposure. Am J Epidmiol 1991;338: 183-94. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vaugelade J. Demographic evaluation of a child health program in Burkina Faso in demographic evaluation of health programmes. Paris: Committee for International Co-operation in National Research in Demography, 1997: 123-30.

- 5.Kristensen I, Aaby P, Jensen H. Routine vaccinations and child survival: follow up study in Guinea-Bissau, West Africa. BMJ 2000;321: 1435-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vaugelade J, Poirier J, Guiella G, Ouedrago R. Problématique et méthodologie des observatoires démographiques dans trois zones du Burkina Faso: Pissila, Niangoloko et Yako-Gourcy (1986-1996). Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso: IRD-UERD, 2000.

- 7.Jensen H. Analysis of multivariate survival data from longitudinal epidemiological studies: with special reference to the impact of routine immunisation in infancy. PhD Thesis. Denmark: University of Copenhagen, 2002.

- 8.Cox. Regression models and life-tables. J Roy Stat Soc Series B, 1972: 187-202.

- 9.Fine P. Commentary: an unexpected finding that needs confirmation or rejection. BMJ 2000;321: 1440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aaby P, Jensen H, Samb B, Cisse B, Sodeman M, Jakobsen M, et al. Differences in female-male mortality after high-titre measles vaccine and association with subsequent vaccination with diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis and inactived poliovirus: reanalysis of the West Afican studies. Lancet 2003;361: 2183-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vaugelade J. Variations de la mortalité saisonnière avant 5 ans selon le biotope en Afrique intertropicale. African population conference, Dakar, Senegal, International Union for the Scientific Study of the Population. Liège, Belgium: IUSSP, 1988: 3.4.51-61.

- 12.Aaby P, Samb B, Simondon F, Seck AM, Knudsen K, Whittle H. Non-specific beneficial effects of measles immunization: analysis of mortality studies from developing countries. BMJ 1995;311: 481-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]