Abstract

Tailed bacteriophages with genomes larger than 200 kbp are classified as Jumbo phages, and are rarely isolated by conventional methods. These phages are designated “jumbo” owing to their most notable features of a large phage virion and large genome size. However, in addition to these, jumbo phages also exhibit several novel characteristics that have not been observed for phages with smaller genomes, which differentiate jumbo phages in terms of genome organization, virion structure, progeny propagation, and evolution. In this review, we summarize available reports on jumbo phages and discuss the differences between jumbo phages and small-genome phages. We also discuss data suggesting that jumbo phages might have evolved from phages with smaller genomes by acquiring additional functional genes, and that these additional genes reduce the dependence of the jumbo phages on the host bacteria.

Keywords: jumbo bacteriophage, genome, diversity, evolution, virion structure

Introduction

Bacteriophages are viruses that infect bacteria and are the most abundant biological entities on earth, exhibiting extremely high, uncharted diversity (Krupovic et al., 2011). Among the characterized phages, the vast majority contain genomes smaller than 200 kbp, and only 93 phages with genomes larger than 200 kbp have been isolated during the past 100 years since the discovery of phages (up to 30 June 2016). More than 80% of these were isolated during the past 3 years, which might be because of the revitalization of phage research (Reardon, 2014) and the progress in next-generation genome sequence technology in recent years. Tailed phages with genomes larger than 200 kbp are classified as “jumbo phages,” and phages of this kind usually harbor large virions. One reason for the rare isolation of jumbo phage is that the large size of the phage virions block their diffusion in semisolid medium, which prevents the formation of visible plaques (Serwer et al., 2007). The other reason is that the method used for removing bacteria with filters. Because of their large size, the jumbo phages might also be removed due to their inability to pass through the pores of the filter. Owing to their rare isolation, jumbo phages are not well known, and no systematic review on jumbo phages is currently available (Hendrix, 2009; Van Etten et al., 2010). In addition to phages with genomes larger than 200 kbp, there are also numerous phages with genomes approaching the 200 kbp size, which will not be discussed here. In this review, we summarize the characteristics, and discuss the diversity and evolution of jumbo phages.

Distribution and hosts

Jumbo phages have been isolated from diverse environments, including water, soil, marine sediments, plant tissues, silkworms, composts, animal feces, and other unknown habitats (Table 1). Among these habitats, jumbo phages have been most frequently isolated from water environments, which might be because the liquid environments benefit the diffusion of jumbo phages and further their infection of host bacteria. Jumbo phages have most often been isolated from Gram-negative host bacterial strains (95.6%), such as strains of genera Synechococcus (44 phages), Pseudomonas (9 phages), Caulobacter (6 phages), Vibrio (6 phages), Erwinia (5 phages), and Aeromonas (5 phages). In contrast, only four jumbo phages infecting Gram-positive bacterial host strains have been isolated, and the host strains of these four phages all belong to the genus Bacillus. It is unclear if jumbo phage infecting only a single genus of Gram-positive bacteria is due to a special feature of Bacillus or just an anomaly of the small number of jumbo phages currently isolated. Further, isolation of phages infecting other Gram-positive strains and study of the interaction of Bacillus jumbo phage with their host strain might provide understanding for this phenomenon.

Table 1.

General features of jumbo phages.

| Phage | Host | Phage taxonomy | Virion size (nm) | Genome length (nt) | No. of CDSs | No. of tRNA | Sample materials | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head | Tail length | ||||||||

| G | Bacillus megaterium | Myoviridae | 160 | 453 | 497,513 | 675 | 20 | NAa | Donelli et al., 1975 |

| vs. | Cronobacter sakazakii | Myoviridae | 115 | 118 | 358,663 | 545 | 26 | Wastewater | Abbasifar et al., 2014 |

| 121Q | Escherichia coli | Myoviridae | 116 | 115 | 348,532 | 611 | 7 | Sewage | Ackermann and Nguyen, 1983 |

| PBECO 4 | Escherichia coli | Myoviridae | 132 | 125 | 348,113 | 551 | 6 | River water | Kim et al., 2013 |

| K64-1 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Myoviridae | NA | NA | 346,602 | 64 | NA | NA | Pan et al., 2015 |

| vB_KleM-RaK2 | Klebsiella sp. | Myoviridae | 123 | 128 | 345,809 | 534 | 5 | NA | Simoliunas et al., 2013 |

| 201ϕ2-1 | Pseudomonas chlororaphis | Myoviridae | 129 | 200 | 316,674 | 461 | 1 | Soil | Thomas et al., 2008 |

| phiPA3 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Myoviridae | 100 | 185 | 309,208 | 379 | 5 | Sewage | Monson et al., 2011 |

| OBP | Pseudomonas fluorescens | Myoviridae | 119 | 191 | 284,757 | 309 | 4 | Compost | Cornelissen et al., 2012 |

| Lu11 | Pseudomonas putida | Myoviridae | 124 | 200 | 280,538 | 391 | 0 | Soil | Adriaenssens et al., 2012 |

| ϕKZ | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Myoviridae | 120 | NA | 280,334 | 306 | 6 | Sewage | Mesyanzhinov et al., 2002 |

| CcrColossus | Caulobacter crescentus | Myoviridae | 292 × 95 | 65 | 279,967 | 448 | 28 | Surface water | Meczker et al., 2014 |

| KTN4 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Myoviridae | 130 | 168 | 279,593 | 368 | NA | Irrigated fields | KT895374 |

| vB_EamM_Special G | Erwinia amylovora | Myoviridae | NA | NA | 273,224 | 324 | 0 | Branches and Blossums | KU886222.1 |

| vB_EamM_Simmy50 | Erwinia amylovora | Myoviridae | NA | NA | 271,088 | 321 | 1 | Bark | KU886223.1 |

| Ea35-70 | Erwinia amylovora | Myoviridae | NA | NA | 271,084 | 318 | 1 | Soil | Yagubi et al., 2014 |

| PA7 | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Myoviridae | NA | NA | 266,743 | 341 | NA | Mudflat | JX233784.1 |

| ϕR1-37 | Yersinia enterocolitica | Myoviridae | 138 | 383 | 262,391 | 367 | 5 | Sewage | Kiljunen et al., 2005 |

| PaBG | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Myoviridae | 136 | 220 | 258,139 | 308 | NA | Lake water | Sykilinda et al., 2014 |

| vB_BpuM_BpSp | Bacillus pumilus | Myoviridae | 137 | 192 | 255,569 | 318 | 0 | Soil | KT895374 |

| P-SSM2 | Prochlorococcus | Myoviridae | 115 | 123 | 252,401 | 334 | 1 | Seawater | Sullivan et al., 2005 |

| AR9 | Bacillus subtilis | Myoviridae | NA | NA | 251,042 | 292 | 1 | NA | Lavysh et al., 2016 |

| ValKK3 | Vibrio alginolyticus | Myoviridae | NA | NA | 248,088 | 390 | NA | Marine sediment | KP671755b |

| nt-1 | Vibrio natriegens | Myoviridae | NA | NA | 247,489 | 379 | 28 | Marine-sediment | Comeau et al., 2014 |

| VH7D | Vibrio harveyi | Myoviridae | NA | NA | 246,964 | 327 | NA | Seawater | NC_023568 |

| ϕpp2 | Vibrio parahaemolyticus | Myoviridae | 90 × 50 | 110 | 246,421 | 383 | 30 | Aquaculture waterway | Lin and Lin, 2012 |

| KVP40 | Vibrio parahaemolyticus | Myoviridae | 140 × 70 | NA | 244,834 | 381 | 30 | Marine-sediment | Miller et al., 2003 |

| ϕEaH2 | Erwinia amylovora | Siphoviridae | NA | NA | 243,050 | 262 | NA | Soil | Domotor et al., 2012 |

| SPN3US | Salmonella enterica | Myoviridae | NA | NA | 240,413 | 264 | 2 | Chicken feces | Lee et al., 2011 |

| VP4B | Vibrio harveyi | Myoviridae | NA | NA | 236,053 | 212 | NA | Ocean | KC131130.1 |

| 65 | Aeromonas salmonicida | Myoviridae | NA | NA | 235,229 | 437 | 16 | NA | Petrov et al., 2010 |

| vB_AbaM_ME3 | Acinetobacter baumanni | Myoviridae | NA | NA | 234,900 | 326 | 4 | Wastewater | Buttimer et al., 2016 |

| Aeh1 | Aeromonas hydrophila | Myoviridae | NA | NA | 233,234 | 352 | 27 | NA | NC_005260 |

| S-SSM7 | Synechococcus | Myoviridae | NA | NA | 232,878 | 319 | 5 | Seawater | Sullivan et al., 2010 |

| CC2 | Aeromonas hydrophila | Myoviridae | NA | NA | 231,743 | 427 | 9 | Sewage | Shen et al., 2012 |

| RSL1 | Ralstonia solanacearum | Myoviridae | 150 | 138 | 231,255 | 343 | 3 | Soil | Yamada et al., 2010 |

| ACG-2014fc | Synechococcus | Myoviridae | NA | NA | 228,143 | 292 | NA | NA | NC_026927 |

| ϕAS5 | Aeromonas salmonicida | Myoviridae | 121 × 71 | 98 | 225,268 | 343 | 24 | River water | Kim et al., 2012 |

| CR5 | Cronobacter sakazakii | Myoviridae | NA | NA | 223,989 | 231 | NA | NA | NC_021531 |

| RSL2 | Ralstonia solanacearum | Myoviridae | NA | NA | 223,932 | 224 | NA | NA | Bhunchoth et al., 2016 |

| CcrRogue | Caulobacter crescentus | Siphoviridae | 205 × 60 | 319 | 223,720 | 350 | 23 | surface water | Meczker et al., 2014 |

| RSF1 | Ralstonia solanacearum | Myoviridae | NA | NA | 222,888 | 230 | NA | NA | Bhunchoth et al., 2016 |

| PX29 | Aeromonas salmonicida | Myoviridae | NA | NA | 222,006 | 330 | 25 | NA | Petrov et al., 2010 |

| CcrKarma | Caulobacter crescentus | Siphoviridae | 205 × 61 | 314 | 221,828 | 353 | 26 | Surface water | Meczker et al., 2014 |

| PAU | Sphingomonas paucimobilis | Myoviridae | NA | NA | 219,372 | 295 | 7 | Silkworms | NC_019521 |

| CcrSwift | Caulobacter crescentus | Siphoviridae | 219 × 63 | 295 | 219,216 | 343 | 27 | surface water | Meczker et al., 2014 |

| 0305Φ8-36 | Bacillus thuringiensis | Myoviridae | 95 | 486 | 218,948 | 246 | 0 | NA | Serwer et al., 2007 |

| CcrMagneto | Caulobacter crescentus | Siphoviridae | 211 × 58 | 293 | 218,929 | 347 | 27 | Surface water | Meczker et al., 2014 |

| ΦEaH1 | Erwinia amylovora | Siphoviridae | NA | NA | 218,339 | 241 | NA | Aerial tissue | Meczker et al., 2014 |

| ΦCbK | Caulobacter crescentus | Siphoviridae | 205 × 56 | 300 | 215,710 | 338 | 26 | Surface water | Meczker et al., 2014 |

| EL | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Myoviridae | 140 | 200 | 211,215 | 201 | NA | NA | Hertveldt et al., 2005 |

| S-SKS1 | Synechococcus | Siphoviridae | NA | NA | 208,007 | 281 | 11 | Seawater | NC_020851 |

NA indicated the data is not available;

The GenBank accession numbers of the not published phage genomes;

Forty-two isolates of phage ACG-2014f are isolated and only the information of the isolate Syn7803C90 is shown as represent.

Big virion and large genome size

The most notable features of jumbo phage are larger phage particles and larger genomes as compared with smaller phages. The biggest known phage is Bacillus megaterium phage G, which has a capsid size of 160 nm, a tail length of 453 nm, and a genome of 497 kbp in length (Table 1; Donelli et al., 1975; Kristensen et al., 2011; Drulis-Kawa et al., 2014). B. megaterium, the host strain of phage G, with a size of about 1.2–1.5 × 2.0–4.0 μm, can only contain ~30 virions of phage G in a single cell. As the phage's capsid size constrains the size of its genome (Hendrix, 2009), jumbo phages with big capsids can package genomes larger in size than phages with smaller capsids. Of note, the genome of phage G is only 87 kbp smaller than the genome of the smallest bacterium, Mycoplasma genitalium (Fraser et al., 1995).

The large genome size enables jumbo phages to contain many genes that do not exist in small-genome phages. For example, all jumbo phages have more genes responsible for genome replication and nucleotide metabolism, and some of the jumbo phages have more than one paralogous gene for DNA polymerase and RNA polymerase (RNAP; Mesyanzhinov et al., 2002; Hertveldt et al., 2005; Kiljunen et al., 2005; Thomas et al., 2007). Among the RNAPs encoded by jumbo phage genomes, most are multi-subunit RNAPs, and some of them have been found in the phage virions (Ceyssens et al., 2014; Yuan and Gao, 2016a). The structural RNAPs are mainly comprised of multiple subunits and may be injected into the host bacteria to start the immediate-early gene transcriptions before the expression of phage and host RNAPs. Transcriptomic analysis of jumbo phage infection revealed that the expression of phage genes may be dependent only on the phages' own RNAPs and independent from the host RNAPs (Ceyssens et al., 2014; Leskinen et al., 2016). Furthermore, jumbo phages also have more proteins for the lysis of the host cell-wall peptidoglycan, such as endolysin, glycoside hydrolase, and chitinase, and many of these proteins were found to be virion components with predicted functions of facilitating phage infection ability (Gill et al., 2012; Yuan and Gao, 2016a). Several jumbo phages also contain more than one tRNA gene (Table 1). For example, phage phiAS5 has 24 tRNAs that contain the anticodon sequences of 16 different amino acids (Kim et al., 2012). tRNA synthetases have been found in the genomes of several jumbo phages, such as Yersinia phage ΦR1-37, phage G, and so on (Kiljunen et al., 2005). The tRNAs in jumbo phage genomes are thought to correspond to codons that are abundant in phage genes, especially those encoding structural proteins, and to increase the translation efficiency of phage-specific genes (Kiljunen et al., 2005). Through their cooperative or independent action, these additional proteins encoded by jumbo phages may substitute for the function of the host proteins that are essential for the life cycle of the smaller-genome phages and reduce the dependence of jumbo phages on their bacterial hosts (O'Donnell et al., 2013). The reduction in dependence of a jumbo phage on its host bacterium might broaden the phage host range and endow jumbo phages with more chance to gain new genetic information from more bacteria by horizontal gene transfer.

Virion composition and structure

Jumbo phages exhibit diverse virion morphology and much more complex virion structure as compared with smaller phages, including different virion sizes and specific substructures of their capsids, and tails (Fokine et al., 2005; Thomas et al., 2007). Compared with the smaller-genome phages, more structural proteins have been identified in the jumbo phages, such as 89 proteins for Pseudomonas phage 201Φ2-1 (four times the number of phage T4 structural proteins; Thomas et al., 2010). Another study found that Pseudomonas phage ΦKZ contained at least 30 phage head proteins among 62 identified structural proteins (Lecoutere et al., 2009). However, some jumbo phages only have a few structural proteins, such as 26 for Aeromonas phage ΦAS5 and 25 for Ralstonia phage ΦRSL1 (Yamada et al., 2010; Kim et al., 2012). Nevertheless, the three-dimensional structure of the jumbo phage ΦRSL1 obtained by cryo-electron microscopy showed that it had a complex head structure formed by at least five different proteins (Effantin et al., 2013).

Several jumbo phages exhibit specific virion structures. For example, the virions of phage 0305Φ8-36 and vB_BpuM_BpSp contain long, wavy, curly tail fibers, which have only been observed in a few phages (Yuan and Gao, 2016a,b). Furthermore, a spool-like protein structure called the “inner body” and encased within genomic DNA was observed in the capsid of phage ΦKZ and other jumbo phages, whereas similar structures have not been identified in smaller-genome phages (Krylov et al., 1984; Sokolova et al., 2014). The “inner body” in the phage capsid is thought to play an important role in DNA packaging and genome ejection during phage virion assembly and infection (Agirrezabala et al., 2005; Cheng et al., 2014). The large genome and virion size, the “inner body,” the wavy, curly tail fiber, and other specific structures of jumbo phages may function to facilitate phage genome packaging, the host recognition, or other processes in the jumbo phage life cycle.

Genome organization and gene expression

The small phage genomes usually possess a modular genome structure, and genes with associated functions forming clusters (Petrov et al., 2006). However, the genes with associated functions in jumbo phage genomes are scattered or only form sub-clusters (Mesyanzhinov et al., 2002; Skurnik et al., 2012; Simoliunas et al., 2013). The timely expression of phage genes is essential for the efficient production of progeny phage. To realize the timely expression of phage genes, different phages have evolved different strategies. Similar to the small-genome phage, the genes of the jumbo phage ΦKZ are transcribed in a typical pattern, and early, middle, and late genes are transcribed in a timely manner by the phage-encoded RNAP (Ceyssens et al., 2014). By contrast, the transcriptions of phage ΦR1-37 genes does not follow the typical pattern and the majority of the genes are constitutively expressed throughout the infection process by the phage-encoded RNAPs (Leskinen et al., 2016). It is noteworthy that, for both these strategies, the regulation of phage genes is under the control of phage-encoded RNAPs, but not the host RNAPs.

Classification and evolution

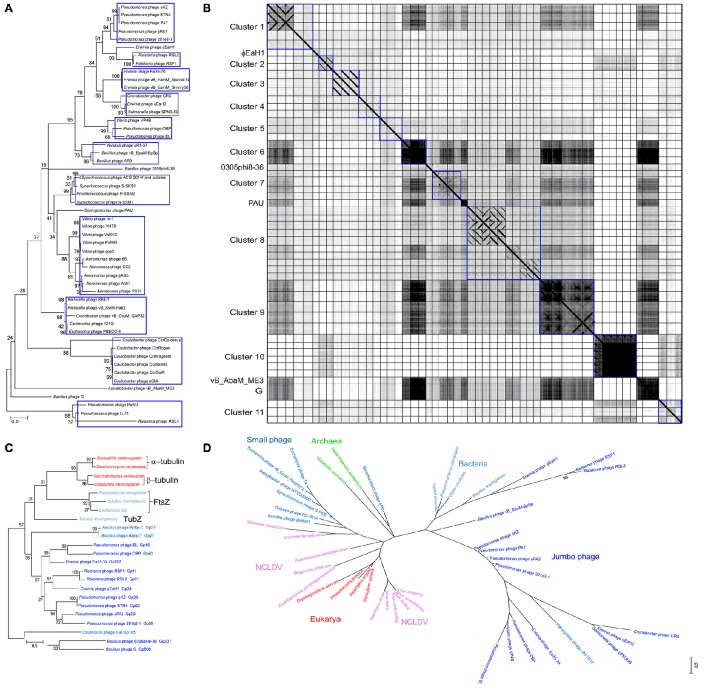

The evolution of jumbo phages has not been well characterized owing to their rare isolation, unavailability of sufficient jumbo phage genomes, and the high genome divergence. To date, based on the morphology similarity and the host range, only some jumbo phages were classified as ΦKZ-like phages (Krylov et al., 2007) and T4-like phages (Petrov et al., 2010), respectively, while no solid genetic evidence is available for the classification of these jumbo phages. Lots of jumbo phages have been designated as a new lineage based on their low genome homology with previously characterized phages (Hardies et al., 2007; Krylov et al., 2007; Yamada et al., 2010; Adriaenssens et al., 2012; Simoliunas et al., 2012; Meczker et al., 2014). Phylogenetic analysis based on the amino acid sequences of the terminase large subunits from 93 jumbo phages revealed that the jumbo phages could be classified into 11 clusters and five singletons (Figure 1A). Comparative genomic analysis of the jumbo phages by using Gepard (Krumsiek et al., 2007), which calculates the similarity of genome sequences and show the similar DNA fragments (word length of 10 and window size of 0) as dot plots, also showed that the jumbo phage could be classified into the same 11 clusters and five singletons (Figure 1B). Based on the phylogenetic and comparative genomic analysis, some phages that used to be classified as ΦKZ-like phages, such as phage Lu11, phage OBP, and phage EL, are now classified into different clusters in this study. Core gene analysis of the jumbo phage also showed that the phage which used to be classified in T4-like phage group should be classified into new cluster. For example, although phage ΦPAS5 has been classified in the T4-like phage group, it only shares 26% core genes with T4 phages (Kim et al., 2012). Otherwise, phage ΦPAS5 and Aeh1, which are classified into the same cluster in this study, share 90% of their genes (Kim et al., 2012). The jumbo phages from each cluster usually infect host strains from the same species or the same genus, and some phages of the same cluster have been isolated from similar ecological environment.

Figure 1.

Phylogenic and comparative genomic analysis of Jumbo phages. The amino acid sequences of the terminase large subunit from 93 jumbo phages (A), the tubulin-like protein from Jumbo phage, bacteria, fungi, and phage with genome near 200 kbp (C), and the B-family DNA polymerase from jumbo phage, small phage, bacteria, archaea, eukarya, and NCLDVs (D), were used for phylogenetic analysis, respectively. The amino acid sequence were alignment by Muscle and the tree were constructed by Maximum Likelihood method with a bootstrap of 1,000 using Mega 6.0 (Tamura et al., 2013). (B) The genome of 52 Jumbo phage were compared by using Gepard (Krumsiek et al., 2007). The phage genome are arrangement in the same order as in Figure 1A. Phages belonging to different clusters are showed in rectangle boxes.

Although the jumbo phages from each cluster showed relatively high genomic similarity (higher than 15%), the phages from different clusters exhibited extremely low or no similarity, suggesting that the jumbo phages have divergent origins. According to previous reports, jumbo phages might be derived from the smaller-genome phages by acquiring novel genetic information and further increasing their genome size and genome function over evolutionary time (Hendrix, 2009). Analysis of the core genes between jumbo phages and small genome phages revealed that the genes essential for phage life cycle are existing both in jumbo- and small-phage (Miller et al., 2003; Kim et al., 2012). Genomic analysis of phage 0305Φ8-36 revealed that the phage genome might be fused from two ancestral virus genomes via the horizontal exchange of a genome module (block of genes) during the evolutionary process (Hardies et al., 2007), while the majority of the jumbo phages might obtain genes from their host by horizontal gene transfer to form larger genomes (Burkal'tseva et al., 2002).

Apart from the jumbo phages, whose propagation mechanism is mainly unclear, there are other large dsDNA viruses include poxviruses, asfarviruses, iridoviruses, ascoviruses, and phycodnaviruses, defined as nucleocytoplasmic large dsDNA viruses (Iyer et al., 2006), and giant viruses that infect amoeba, including mimiviruses, marseilleviruses, pandoraviruses, pithoviruses, faustoviruses, and Mollivirus sibericum (Forterre and Gaia, 2016). The replicative cycle of these large and giant dsDNA viruses include the presence in the host cytoplasm of viral factories that produce the progeny viruses (Netherton and Wileman, 2011). Such viral factories were hypothesized to be at the origin of the modern eukaryotic nucleus (Forterre and Gaia, 2016). Jumbo phages exhibit similar replication characteristics to the eukaryotic NCLDVs. The tubulin-like protein PhuZ of phage 201Φ2-1 can form a spindle and position the phage genome DNA to the mid-cell region of the bacterial host; subsequently, the encapsidated DNA forms a rosette-like structure surrounded by a larger DNA mass, which, to some extent, resembles the viral factory of NCLDVs (Kraemer et al., 2012). Proteins homologous to PhuZ have also been found in the genomes of several jumbo phages and phages with genomes near 200 kbp. Phylogenetic analysis of the homologous proteins of PhuZ reveals that the jumbo phages are evolutionary closely to phages with genome near 200 kbp, but distinct from the small genome phages and the cellular microorganisms (Figure 1C). The evolutionary relationships of jumbo phage based PhuZ-like protein are consistent with that based on the terminase large subunit (Figure 1A) and the B-family DNA-polymerase (Figure 1D). Though the smaller-genome phage do not encode tubulin-like protein in their own genomes, they also engage the tubulin-like protein from the host bacteria to facilitate the phage genome replication (Munoz-Espin et al., 2009). Formation of viral factory-like structures by jumbo phages and large viruses creates a platform to concentrate virus replication-associated proteins, virus genomes, and host proteins required for replication, and also protects viruses from host defenses (Netherton and Wileman, 2011), which might benefit the virus propagation. Except for the feature of forming viral factories, NCLDVs and giant viruses of amoeba also have more genes associated with genome replication, nucleotide metabolism, and some other biochemical processes (Legendre et al., 2014). Although jumbo phages, NCLDVs, and giant viruses of amoeba exhibit several similar features, they are evolutionary distant (Figure 1D). The jumbo phages are much more closely related to the bacteria and archaea, while the NCLDVs show a closer evolutionary relationship with the eukaryotes.

Conclusion and perspective

More recently, larger viruses have been isolated, and their discovery has greatly enriched our understanding of biological entity diversity and evolution (Bhunchoth et al., 2015; Sharma et al., 2015). Jumbo phages have been isolated from diverse niches and exhibit extremely high genetic diversity. However, generally speaking, the jumbo phages exhibit several common features that differentiate them from the smaller-genome phages. First, the jumbo phages have notably bigger virions and larger genomes. Second, the genomes of the jumbo phages form non-modular structures, and genes with associated functions are scattered throughout the genome. Third, they contain more genes associated with biochemical processes and more than one paralog of essential genes for the phage life cycle. Fourth, they contain structural RNAPs in phage virion with the function of controlling jumbo phage gene expression. Fifth, the jumbo phages are evolutionarily distant from the small genome phages. Despite the common features that differentiate them from smaller-genome phages, jumbo phages show more divergent characteristics among each other, such as low genome similarity, individual virion substructure, and different propagation mechanisms.

For the purpose of archiving a greater understanding of the jumbo phages, several areas need to be studied further. First, isolation and complete genomic sequencing of more jumbo phages. In order to isolate novel jumbo phages, re-isolation of environmental samples by reducing the agar concentration in the upper medium or a deep metagenomic sequencing of environmental samples may be effective. Second, further study the interaction mechanism between jumbo phages and their host bacteria, including the phage propagation mechanism. Our current knowledge of phages is mainly based on the study of smaller-genome phage. Although the jumbo phages might have evolved from the smaller-genome phages, they show many differences from the smaller-genome phages in terms of genome structure and propagation strategy. Third, functional analysis of the genes with more than one paralog and the structural RNAPs. The additional paralogous genes and structural RNAPs might reduce the dependence of jumbo phages on their host bacteria. However, the functions of these genes for the jumbo phage life cycle have mainly been ascribed based on the bioinformatic analysis, and no experimental evidence is available. Functional analysis of these genes will provide a greater understanding of the phage-host interaction and evolution of jumbo phages. Fourth, analyze the evolution and the origin of jumbo phages. The large genomes of jumbo phages are thought to have evolved from small phage genomes by acquisition of novel genetic information during the evolutionary process, which led to a reduced dependence of phages on their host strain. Study of the evolution and origin of jumbo phages could provide knowledge for understanding the origin of cellular biological entities and the evolution of biological entities from cell-dependent to cell-independent status.

Author contributions

YH designed and drafted the manuscript. YH and MG revised the manuscript. All author approved of the final content of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31500155, 31170123).

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Abbasifar R., Griffiths M. W., Sabour P. M., Ackermann H. W., Vandersteegen K., Lavigne R., et al. (2014). Supersize me: cronobacter sakazakii phage GAP32. Virology 460, 138–146. 10.1016/j.virol.2014.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ackermann H. W., Nguyen T. M. (1983). Sewage coliphages studied by electron-microscopy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 45, 1049–1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adriaenssens E. M., Mattheus W., Cornelissen A., Shaburova O., Krylov V. N., Kropinski A. M., et al. (2012). Complete genome sequence of the giant Pseudomonas Phage Lu11. J. Virol. 86, 6369–6370. 10.1128/JVI.00641-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agirrezabala X., Martin-Benito J., Caston J. R., Miranda R., Valpuesta M., Carrascosa J. L. (2005). Maturation of phage T7 involves structural modification of both shell and inner core components. EMBO J. 24, 3820–3829. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhunchoth A., Blanc-Mathieu R., Mihara T., Nishimura Y., Askora A., Phironrit N., et al. (2016). Two asian jumbo phages, phi RSL2 and phi RSF1, infect Ralstonia solanacearum and show common features of phi KZ-related phages. Virology 494, 56–66. 10.1016/j.virol.2016.03.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhunchoth A., Phironrit N., Leksomboon C., Chatchawankanphanich O., Kotera S., Narulita E., et al. (2015). Isolation of Ralstonia solanacearum-infecting bacteriophages from tomato fields in Chiang Mai, Thailand, and their experimental use as biocontrol agents. J. Appl. Microbiol. 118, 1023–1033. 10.1111/jam.12763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkal'tseva M. V., Krylov V. N., Pleteneva E. A., Shaburova O. V., Krylov S. V., Volkart G., et al. (2002). Phenogenetic characterization of a group of giant φ KZ-like bacteriophages of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Genetika 38, 1470–1479. 10.1023/A:1021190826111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buttimer C., O'Sullivan L., Elbreki M., Neve H., McAuliffe O., Ross R. P., et al. (2016). Genome sequence of jumbo phage vB_AbaM_ME3 of Acinetobacter baumanni. Genome Announc. 4:e00431–16. 10.1128/genomeA.00431-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceyssens P. J., Minakhin L., Van den Bossche A., Yakunina M., Klimuk E., Blasdel B., et al. (2014). Development of giant bacteriophage phi KZ Is independent of the host transcription apparatus. J. Virol. 88, 10501–10510. 10.1128/JVI.01347-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng N., Wu W., Watts N. R., Steven A. C. (2014). Exploiting radiation damage to map proteins in nucleoprotein complexes: the internal structure of bacteriophage T7. J. Struct. Biol. 185, 250–256. 10.1016/j.jsb.2013.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comeau A. M., Arbiol C., Krisch H. M. (2014). Composite conserved promoter-terminator motifs (PeSLs) that mediate modular shuffling in the diverse T4-Like Myoviruses. Genome Biol. Evol. 6, 1611–1619. 10.1093/gbe/evu129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelissen A., Hardies S. C., Shaburova O. V., Krylov V. N., Mattheus W., Kropinski A. M., et al. (2012). Complete genome sequence of the giant virus OBP and comparative genome analysis of the diverse phi KZ-related phages. J. Virol. 86, 1844–1852. 10.1128/JVI.06330-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domotor D., Becsagh P., Rakhely G., Schneider G., Kovacs T. (2012). Complete genomic sequence of Erwinia amylovora phage PhiEaH2. J. Virol. 86, 10899–10899. 10.1128/JVI.01870-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donelli G., Dore E., Frontali C., Grandolfo M. E. (1975). Structure and physico-chemical properties of bacteriophage G. III. A homogeneous DNA of molecular weight 5 times 10(8). J. Mol. Biol. 94, 555–565. 10.1016/0022-2836(75)90321-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drulis-Kawa Z., Olszak T., Danis K., Majkowska-Skrobek G., Ackermann H. W. (2014). A giant Pseudomonas phage from Poland. Arch. Virol. 159, 567–572. 10.1007/s00705-013-1844-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Effantin G., Hamasaki R., Kawasaki T., Bacia M., Moriscot C., Weissenhorn W., et al. (2013). Cryo-electron microscopy three-dimensional structure of the jumbo phage Phi RSL1 infecting the phytopathogen Ralstonia solanacearum. Structure 21, 298–305. 10.1016/j.str.2012.12.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fokine A., Kostyuchenko V. A., Efimov A. V., Kurochkina L. P., Sykilinda N. N., Robben J., et al. (2005). A three-dimensional cryo-electron microscopy structure of the bacteriophage phiKZ head. J. Mol. Biol. 352, 117–124. 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forterre P., Gaia M. (2016). Giant viruses and the origin of modern eukaryotes. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 31, 44–49. 10.1016/j.mib.2016.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser C. M., Gocayne J. D., White O., Adams M. D., Clayton R. A., Fleischmann R. D., et al. (1995). The minimal gene complement of mycoplasma-genitalium. Science 270, 397–403. 10.1126/science.270.5235.397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill J. J., Berry J. D., Russell W. K., Lessor L., Escobar-Garcia D. A., Hernandez D., et al. (2012). The Caulobacter crescentus phage phiCbK: genomics of a canonical phage. BMC Genomics 13:542. 10.1186/1471-2164-13-542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardies S. C., Thomas J. A., Serwer P. (2007). Comparative genomics of Bacillus thuringiensis phage 0305 phi 8-36: defining patterns of descent in a novel ancient phage lineage. Virol. J. 4:97. 10.1186/1743-422X-4-97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrix R. W. (2009). Jumbo bacteriophages. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 328, 229–240. 10.1007/978-3-540-68618-7_7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertveldt K., Lavigne R., Pleteneva E., Sernova N., Kurochkina L., Korchevskii R., et al. (2005). Genome comparison of Pseudomonas aeruginosa large phages. J. Mol. Biol. 354, 536–545. 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.08.075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer L. A., Balaji S., Koonin E. V., Aravind L. (2006). Evolutionary genomics of nucleo-cytoplasmic large DNA viruses. Virus Res. 117, 156–184. 10.1016/j.virusres.2006.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiljunen S., Hakala K., Pinta E., Huttunen S., Pluta P., Gador A., et al. (2005). Yersiniophage phi R1-37 is a tailed bacteriophage having a 270 kb DNA genome with thymidine replaced by deoxyuridine. Microbiology-SGM 151, 4093–4102. 10.1099/mic.0.28265-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. H., Son J. S., Choi Y. J., Choresca C. H., Shin S. P., Han J. E., et al. (2012). Complete genome sequence and characterization of a broad-host range T4-like bacteriophage phiAS5 infecting Aeromonas salmonicida subsp salmonicida. Vet. Microbiol. 157, 164–171. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2011.12.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M. S., Hong S. S., Park K., Myung H. (2013). Genomic analysis of bacteriophage PBECO4 infecting Escherichia coli O157:H7. Arch. Virol. 158, 2399–2403. 10.1007/s00705-013-1718-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer J. A., Erb M. L., Waddling C. A., Montabana E. A., Zehr E. A., Wang H. N., et al. (2012). A phage tubulin assembles dynamic filaments by an atypical mechanism to center viral DNA within the host cell. Cell 149, 1488–1499. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristensen D. M., Cai X. X., Mushegian A. (2011). Evolutionarily conserved orthologous families in phages are relatively rare in their prokaryotic hosts. J. Bacteriol. 193, 1806–1814. 10.1128/JB.01311-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krumsiek J., Arnold R., Rattei T. (2007). Gepard: a rapid and sensitive tool for creating dotplots on genome scale. Bioinformatics 23, 1026–1028. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krupovic M., Prangishvili D., Hendrix R. W., Bamford D. H. (2011). Genomics of bacterial and archaeal viruses: dynamics within the prokaryotic virosphere. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 75, 610–635. 10.1128/MMBR.00011-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krylov V. N., Dela Cruz D. M., Hertveldt K., Ackermann H. W. (2007). “phi KZ-like viruses,” a proposed new genus of myovirus bacteriophages. Arch. Virol. 152, 1955–1959. 10.1007/s00705-007-1037-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krylov V. N., Smirnova T. A., Minenkova I. B., Plotnikova T. G., Zhazikov I. Z., Khrenova E. A. (1984). Pseudomonas Bacteriophage Phi-Kz contains an inner body in its capsid. Can. J. Microbiol. 30, 758–762. 10.1139/m84-116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavysh D., Sokolova M., Minakhin L., Yakunina M., Artamonova T., Kozyavkin S., et al. (2016). The genome of AR9, a giant transducing Bacillus phage encoding two multisubunit RNA polymerases. Virology 495, 185–196. 10.1016/j.virol.2016.04.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecoutere E., Ceyssens P. J., Miroshnikov K. A., Mesyanzhinov V. V., Krylov V. N., Noben J. P., et al. (2009). Identification and comparative analysis of the structural proteomes of phiKZ and EL, two giant Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteriophages. Proteomics 9, 3215–3219. 10.1002/pmic.200800727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. H., Shin H., Kim H., Ryu S. (2011). Complete Genome sequence of salmonella bacteriophage SPN3US. J. Virol. 85, 13470–13471. 10.1128/JVI.06344-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legendre M., Bartoli J., Shmakova L., Jeudy S., Labadie K., Adrait A., et al. (2014). Thirty-thousand-year-old distant relative of giant icosahedral DNA viruses with a pandoravirus morphology. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 4274–4279. 10.1073/pnas.1320670111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leskinen K., Blasdel B. G., Lavigne R., Skurnik M. (2016). RNA-Sequencing reveals the progression of phage-host interactions between phi R1-37 and Yersinia enterocolitica. Viruses-Basel 8:111. 10.3390/v8040111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y. R., Lin C. S. (2012). Genome-wide characterization of Vibrio phage phipp2 with unique arrangements of the mob-like genes. BMC Genomics 13:224. 10.1186/1471-2164-13-224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meczker K., Domotor D., Vass J., Rakhely G., Schneider G., Kovacs T. (2014). The genome of the Erwinia amylovora phage PhiEaH1 reveals greater diversity and broadens the applicability of phages for the treatment of fire blight. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 350, 25–27. 10.1111/1574-6968.12319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesyanzhinov V. V., Robben J., Grymonprez B., Kostyuchenko V. A., Bourkaltseva M. V., Sykilinda N. N., et al. (2002). The genome of bacteriophage phi KZ of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Mol. Biol. 317, 1–19. 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller E. S., Heidelberg J. F., Eisen J. A., Nelson W. C., Durkin A. S., Ciecko A., et al. (2003). Complete genome sequence of the broad-host-range vibriophage KVP40: comparative genomics of a T4-related bacteriophage. J. Bacteriol. 185, 5220–5233. 10.1128/JB.185.17.5220-5233.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monson R., Foulds I., Foweraker J., Welch M., Salmond G. P. C. (2011). The Pseudomonas aeruginosa generalized transducing phage phi PA3 is a new member of the phi KZ-like group of “jumbo” phages, and infects model laboratory strains and clinical isolates from cystic fibrosis patients. Microbiology-SGM 157, 859–867. 10.1099/mic.0.044701-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz-Espin D., Daniel R., Kawai Y., Carballido-Lopez R., Castilla-Llorente V., Errington J., et al. (2009). The actin-like MreB cytoskeleton organizes viral DNA replication in bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 13347–13352. 10.1073/pnas.0906465106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Netherton C. L., Wileman T. (2011). Virus factories, double membrane vesicles and viroplasm generated in animal cells. Curr. Opin. Virol. 1, 381–387. 10.1016/j.coviro.2011.09.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell M., Langston L., Stillman B. (2013). Principles and concepts of DNA replication in Bacteria, Archaea, and Eukarya. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 5:a010108. 10.1101/cshperspect.a010108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Y. J., Lin T. L., Lin Y. T., Su P. A., Chen C. T., Hsieh P. F., et al. (2015). Identification of capsular types in carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae strains by wzc sequencing and implications for capsule depolymerase treatment. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 59, 1038–1047. 10.1128/AAC.03560-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrov V. M., Nolan J. M., Bertrand C., Levy D., Desplats C., Krisch H. M., et al. (2006). Plasticity of the gene functions for DNA replication in the T4-like phages. J. Mol. Biol. 361, 46–68. 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.05.071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrov V. M., Ratnayaka S., Nolan J. M., Miller E. S., Karam J. D. (2010). Genomes of the T4-related bacteriophages as windows on microbial genome evolution. Virol. J. 7:292. 10.1186/1743-422X-7-292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reardon S. (2014). Phage therapy gets revitalized. Nature 510, 200–200. 10.1038/510015a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serwer P., Hayes S. J., Thomas J. A., Hardies S. C. (2007). Propagating the missing bacteriophages: a large bacteriophage in a new class. Virol. J. 4:21. 10.1186/1743-422X-4-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma V., Colson P., Chabrol O., Scheid P., Pontarotti P., Raoult D. (2015). Welcome to pandoraviruses at the “Fourth TRUC” club. Front. Microbiol. 6:423. 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen C. J., Liu Y. J., Lu C. P. (2012). Complete genome sequence of Aeromonas hydrophila Phage CC2. J. Virol. 86, 10900–10900. 10.1128/JVI.01882-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoliunas E., Kaliniene L., Truncaite L., Klausa V., Zajanckauskaite A., Meskys R. (2012). Genome of Klebsiella sp.-Infecting Bacteriophage vB_KleM_RaK2. J. Virol. 86, 5406–5406. 10.1128/JVI.00347-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoliunas E., Kaliniene L., Truncaite L., Zajanckauskaite A., Staniulis J., Kaupinis A., et al. (2013). Klebsiella phage vB_KleM-RaK2 - a giant singleton virus of the family Myoviridae. PLoS ONE 8:e60717. 10.1371/journal.pone.0060717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skurnik M., Hyytiainen H. J., Happonen L. J., Kiljunen S., Datta N., Mattinen L., et al. (2012). Characterization of the genome, proteome, and structure of yersiniophage varphiR1-37. J. Virol. 86, 12625–12642. 10.1128/JVI.01783-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokolova O. S., Shaburova O. V., Pechnikova E. V., Shaytan A. K., Krylov S. V., Kiselev N. A., et al. (2014). Genome packaging in EL and Lin68, two giant phiKZ-like bacteriophages of P. aeruginosa. Virology 468–470, 472–478. 10.1016/j.virol.2014.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan M. B., Coleman M. L., Weigele P., Rohwer F., Chisholm S. W. (2005). Three Prochlorococcus cyanophage genomes: signature features and ecological interpretations. Plos Biol. 3:e144. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan M. B., Huang K. H., Ignacio-Espinoza J. C., Berlin A. M., Kelly L., Weigele P. R., et al. (2010). Genomic analysis of oceanic cyanobacterial myoviruses compared with T4-like myoviruses from diverse hosts and environments. Environ. Microbiol. 12, 3035–3056. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02280.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sykilinda N. N., Bondar A. A., Gorshkova A. S., Kurochkina L. P., Kulikov E. E., Shneider M. M., et al. (2014). Complete genome sequence of the novel giant Pseudomonas Phage PaBG. Genome Announc. 2:e00929–13. 10.1128/genomeA.00929-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K., Stecher G., Peterson D., Filipski A., Kumar S. (2013). MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 2725–2729. 10.1093/molbev/mst197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J. A., Hardies S. C., Rolando M., Hayes S. J., Lieman K., Carroll C. A., et al. (2007). Complete genomic sequence and mass spectrometric analysis of highly diverse, atypical Bacillus thuringiensis phage 0305 phi 8-36. Virology 368, 405–421. 10.1016/j.virol.2007.06.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J. A., Rolando M. R., Carroll C. A., Shen P. S., Belnap D. M., Weintraub S. T., et al. (2008). Characterization of Pseudomonas chlororaphis myovirus 201 phi 2-1 via genomic sequencing, mass spectrometry, and electron microscopy. Virology 376, 330–338. 10.1016/j.virol.2008.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J. A., Weintraub S. T., Hakala K., Serwer P., Hardies S. C. (2010). Proteome of the large Pseudomonas myovirus 201 phi 2-1: delineation of proteolytically processed virion proteins. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 9, 940–951. 10.1074/mcp.M900488-MCP200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Etten J. L., Lane L. C., Dunigan D. D. (2010). DNA viruses: the really big ones (Giruses). Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 64, 83–99. 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagubi A. I., Castle A. J., Kropinski A. M., Banks T. W., Svircev A. M. (2014). Complete genome sequence of Erwinia amylovora bacteriophage vB_EamM_Ea35-70. Genome Announc. 2:e00413–14. 10.1128/genomeA.00413-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada T., Satoh S., Ishikawa H., Fujiwara A., Kawasaki T., Fujie M., et al. (2010). A jumbo phage infecting the phytopathogen Ralstonia solanacearum defines a new lineage of the Myoviridae family. Virology 398, 135–147. 10.1016/j.virol.2009.11.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Y., Gao M. (2016a). Proteomic analysis of a novel bacillus jumbo phage revealing glycoside hydrolase as structural component. Front. Microbiol. 7:745. 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Y., Gao M. (2016b). Characteristics and complete genome analysis of a novel jumbo phage infecting pathogenic Bacillus pumilus causing ginger rhizome rot disease. Arch. Virol. 161, 3597–3600. 10.1007/s00705-016-3053-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]