Abstract

This review discusses the biology and behavior of Propionibacterium acnes (P. acnes), a dominant bacterium species of the skin biogeography thought to be associated with transmission, recurrence and severity of disease. More specifically, we discuss the ability of P. acnes to invade and persist in epithelial cells and circulating macrophages to subsequently induce bouts of sarcoidosis, low-grade inflammation and metastatic cell growth in the prostate gland. Finally, we discuss the possibility of P. acnes infiltrating the brain parenchyma to indirectly contribute to pathogenic processes in neurodegenerative disorders such as those observed in Parkinson's disease (PD).

Keywords: Propionibacterium acnes, sarcoidosis, BPH, prostate cancer, Parkinson disease

General overview

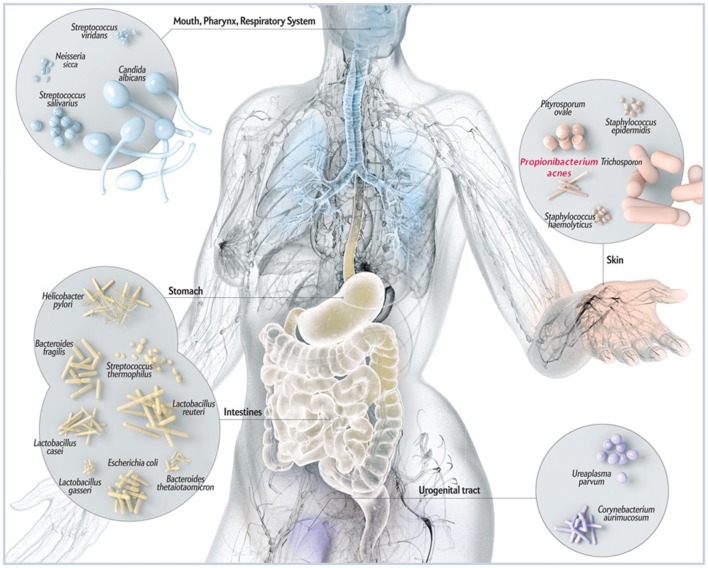

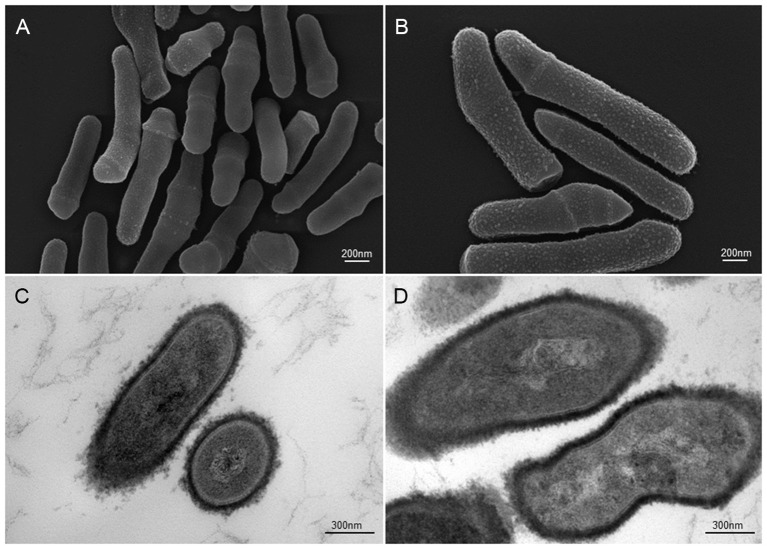

A large fraction of microorganisms not only reside within us but also live on us. Indeed, the human skin harbors a heterogeneous mix of mostly non-pathogenic bacteria, fungi and viruses that probably contribute to skin surface health (Figure 1). Propionibacterium acnes (P. acnes) is a ubiquitous, slow growing, rod-shaped, non-spore forming, Gram-positive anaerobe (Figure 2) found across body sites, including sebaceous follicles of the face and neck (Funke et al., 1997; Grice and Segre, 2011; Findley and Grice, 2014). It is often considered part of our commensal microbiota at barrier sites (Cogen et al., 2008) which is established via mechanisms of adaptive immune tolerance during the early neonate period (Scharschmidt et al., 2015). Although the topographical distribution of the anaerobe in sebaceous sites is significant, the spatial and personal distribution of P. acnes is more individual-specific than site-specific (Oh et al., 2014). Moreover, the biogeography and individuality of P. acnes is highly dynamic as changes in health or changes in pH, temperature, moisture and/or sebum content may also affect the range of niches occupied by the microorganism (Grice et al., 2009). Similar to the distribution of skin microbes, skin conditions can also shape the function of P. acnes in terms of pathogen expansion in disease. For example, P. acnes has been linked to skin insults such as acne vulgaris in the face and neck, and progressive macular hypermelanosis on the back (Bojar and Holland, 2004; Kurokawa et al., 2009; Barnard et al., 2016). In addition, certain disease-associated phylotypes of P. acnes have the ability to persist on body implants and surgical devices causing a wide-range of post-operative infectious conditions, such as endocarditis, endophthalmitis and intravascular nervous system infections (Perry and Lambert, 2011; Portillo et al., 2013). The untoward features of P. acnes also extend to the prostate gland where tissue invasion and intracellular deposition of the bacterium has been frequently noted in glandular epithelial cells and circulating macrophages; a phenomenon thought to indirectly contribute to benign prostate hyperplasia (BPH) and prostate cancer (Tanabe et al., 2006; Alexeyev et al., 2007; Fassi-Fehri et al., 2011; Mak et al., 2012; Bae et al., 2014; Davidsson et al., 2016). However, it is not clear what the underlying mechanisms used by P. acnes are to induce infection, inflammation and/or metastasis outside the skin. What is known with some certainty is that bacteria-infected keratinocytes, sebocytes and/or adipocytes secrete several pro-inflammatory chemokines and cytokines as well as anti-microbial factors (e.g., cathelicidin) hinting at specific disease mechanisms (Graham et al., 2004; Nagy et al., 2006; Lee et al., 2010; Zhou et al., 2015; Sanford et al., 2016; Yu et al., 2016).

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of common microbes found at barrier sites in humans including P. acnes. While P. acnes is present on all external and internal surfaces (i.e., oral and gastrointestinal epithelia, conjunctiva), it is most prevalent on the human skin. There it resides in hair follicles of the face and back where it is associated with the common skin disease acne vulgaris. By most, P acnes is still considered a mostly benign and commensal microorganism, however, reports about its malicious opportunistic side are increasing. Adapted and with kind permission from Bryan Christie Design (http://bryanchristiedesign.com/).

Figure 2.

Scanning and transmission electron microscopic (SEM and TEM) images of P. acnes strain KPA (A, B = SEM; C, D = TEM). Recent advances in isolation and culturing techniques are revealing that P. acnes infections have been grossly underestimated shedding a new light on this opportunistic bacterial species. Microscopy by Volker Brinkmann, Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology, Berlin, Germany. Scale bar = 200/300nm.

Sarcoidosis

Sarcoidosis is a disease of unknown etiology that leads to inflammation in organs as diverse as lungs, liver, skin and lymphatics. A putative link of sarcoidosis with P. acnes was first proposed when the bacterium was isolated from sarcoid lesions of the skin and lymph nodes (Eishi et al., 2002; Yamada et al., 2002). These findings have been significantly corroborated (de Brouwer et al., 2015), and further expanded by various in vitro experiments demonstrating the invasion capacity of P. acnes in HEK293T (human embryonic kidney) and A549 (human alveolar epithelial carcinoma) cell lines (Tanabe et al., 2006). Most recent work in sarcoid broncho-alveolar lavage (BAL) fluid and cells showed significant upregulation of a P. acnes-specific immune response (Schupp et al., 2015). In addition, experiments in mice have shown that viable P. acnes can induce pulmonary granulomas similar to those observed in sarcoidosis patients (Werner et al., 2017). A general overview detailing the link between sarcoidosis and P. acnes is further given by Eishi (2013).

Studies attempting to characterize the signaling pathways activated by P. acnes during infection showed that nuclear factor-kappaB [NF-κB], a transcriptional factor that regulates the expression of genes involved in immune and inflammatory cascades is activated by P. acnes (Kim et al., 2002). More broadly, toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) was shown to be a critical receptor for the NF-κB-dependent response to P. acnes, revealing the capacity of this bacterium to provoke the selective activation of innate immunity genes (Inohara and Nuñez, 2001; Chamaillard et al., 2003; Moreira and Zamboni, 2012). Furthermore, the role of host genetics was examined in sarcoidosis cases that were associated with P. acnes infection. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD) of proteins NOD1 and NOD2 were correlated with P. acnes infection among 73 sarcoidosis patients with 52 interstitial pneumonia and 215 healthy controls (Tanabe et al., 2006). NOD1 and NOD2 are intracellular pattern recognition receptors that can sense bacterial molecules such as peptidoglycan moieties. Along the same lines, in vitro experiments have shown that internalization of P. acnes into HEK293T cells can result in activation of NOD1 and NOD2, suggesting a disease mechanism based on chronic inflammation or local immunosuppression (Tanabe et al., 2006). These findings also suggest that invasive P. acnes can act as bacterial ligands to cause aberrant NOD receptor activation in certain individuals with long-lasting susceptibility to sarcoidosis. However, future experiments have to clarify the exact mechanistic chronology of whether or how P. acnes-mediated aberrant NF-κB activation may induce granuloma formation in a NOD1/NOD2-dependent manner.

Although invasive P. acnes could be a possible etiology of sarcoidosis and perhaps other diseases, elucidating causation and correlation between P. acnes infection and pathology is murky as bacterial strain heterogeneity, host genetics as well as host's environments must be considered whenever a study links a microbiome to a disease state.

Benign prostate hyperplasia (BPH) and prostate cancer

Chronic or recurrent inflammatory processes have long been implicated in the progression of BPH and prostate cancer (De Marzo et al., 1999; Nelson et al., 2004; Sfanos et al., 2014). Inflammation is attributed to the presence of specific biomarkers such as elevated interleukin (IL)-6, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) and the acute phase protein, C reactive protein (Mechergui et al., 2009; Menschikowski et al., 2013; Yu et al., 2015). Recent work on urological fluids (i.e., urine, seminal fluid, prostatic secretions) as well as prostate biopsies suggests a significant conditional shift toward certain microbial species which may be used as a diagnostic index (Yu et al., 2015; Ni et al., 2016).

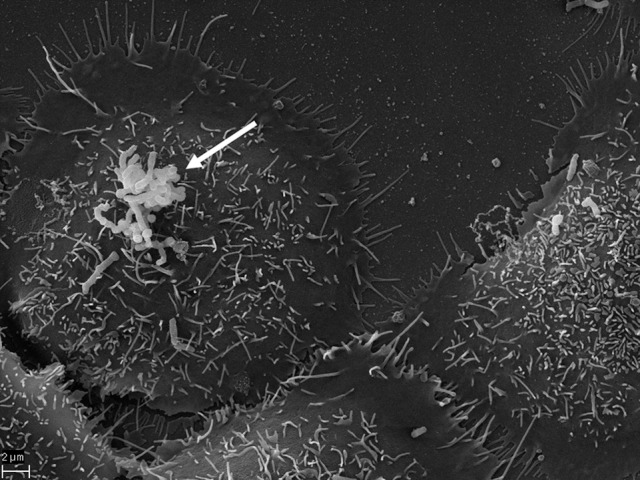

A good amount of work is suggesting that the specific association of P. acnes with the prostate and the invasion of prostate epithelial cells in particular (Figure 3) may contribute to the pathology of BPH or prostate cancer with an inflammatory component (Sfanos et al., 2013; Davidsson et al., 2016). However, it is currently unclear whether P. acnes represents a true infectious agent of the prostate, a commensal or accidental prostate microbion. It is plausible that prostate-located P. acnes are derived from the skin that are accidentally introduced, for instance during a prostate biopsy—a viewpoint that should raise concerns with certain diagnostic workup scenarios.

Figure 3.

SEM of P. acnes strain P6 (arrow) in vitro on cultured prostate epithelial cells RWPE1. The prostate epithelial cell-invasive behavior of P. acnes is well documented in both, in vivo and cell-based studies where a vimentin-mediated invasion process looks likely (Mak et al., 2012). Microscopy by Volker Brinkmann, Max Planck Institute for Infection Biology, Berlin, Germany. Scale bar = 2 μm.

Whatever the route of entry or pathogenic potential, a significant number of prostate tissues obtained through transurethral resection for BPH, or radical prostatectomy for cancer, were previously tested positive for P. acnes aggregates apparently residing within roving macrophages (Alexeyev et al., 2007; Bae et al., 2014). Additional reports based on human samples have provided further evidence for a link between BPH or prostate cancer and P. acnes using various technical approaches, including cultivation, confocal microscopy for visualization of the bacterium and in situ hybridization, immunohistochemistry (Figure 4) and PCR-based profiling of bacterial 16S rRNA (Hochreiter et al., 2000; Cohen et al., 2005; Sfanos et al., 2008; Fassi-Fehri et al., 2011; Bae et al., 2014; Davidsson et al., 2016). Further evidence comes from animal studies indicating that inoculation of P. acnes into the murine or rat prostate and bladder leads to an overt, long-term inflammatory response and a wide-range of cellular disturbances within the prostate gland (Olsson et al., 2012; Shinohara et al., 2013).

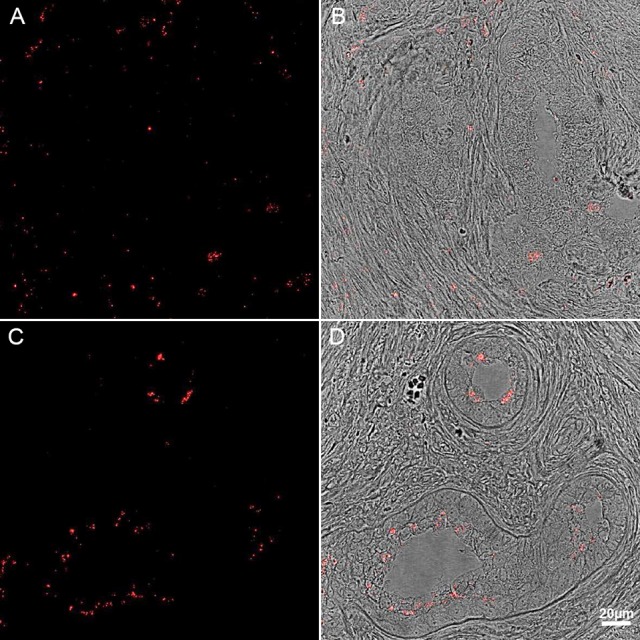

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemistry of human prostate tissue samples stained with P. acnes antibody (red). Adapted with permission from Fassi-Fehri et al., 2011 (Supplementary Figure 2B). Presence of P. acnes in human prostate tissue samples with benign prostatic hyperplasia (A,B); or adenocarcinoma (C,D). Extensive bacterial load was detected in both cases.

Attempts to phylogenetically analyze disease-associated P. acnes strains from cancerous prostate glands have revealed that most prostate isolates belong to phylogenetic clades that are rare on human skin, indicating that a skin-derived contamination during sampling is unlikely (Mak et al., 2013; Davidsson et al., 2016). Along the same lines, similar inflammatory pathways as those described for sarcoidosis, including NF-κB, IL-6, STAT3 and COX2, appear to be activated by P. acnes both under in situ and in vitro conditions (Drott et al., 2010; Fassi-Fehri et al., 2011; Mak et al., 2013; Tsai et al., 2013; Bae et al., 2014). Although the precise etiology for these inflammatory changes is not yet clear, several membrane-bound pattern recognition receptor pathways are broadly distributed in mammalian urinary and genital systems that avidly recognize bacterial and viral components (Jorgensen and Seed, 2012; Gambara et al., 2013). These host cell receptors, for example TLRs, promote cytokine production which is a core feature of innate immunity against microbial pathogens. Collectively, these findings suggest that through their capacity to trigger various aspects of immunity, invading P. acnes can act as primary driver and/or amplifier of disease severity.

Spondylodiscitis and back pain

One of several post-operative complications involving P. acnes is inflammation of the intervertebral disk and the surrounding intervertebral space (diskitis) following discectomy (Harris et al., 2005). Concomitant degenerative infection of adjacent vertebrae (spondylodiscitis) can be a common feature and the root cause for serious neurological damage and pain if treatment is delayed (Uçkay et al., 2010). Aside from unintentional surgical introduction right into the vertebral column, pathogens can also arrive through the arterial and venous spinal blood supply (hematogenous spreading). While Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, and Proteus species are most commonly isolated, P. acnes is the most abundant anaerobic pathogen in this context and likely underreported due to culturing challenges. There has been some clinical evidence that patients with herniated nuclear (nucleus pulposus) disk material infected with anaerobic pathogens in general, and P. acnes in particular, are more likely develop inflammation and edema of the adjacent vertebrae (Modic changes type I) and back pain (Albert et al., 2013; Urquhart et al., 2015). Clinical and animal-based follow-ups are now corroborating the initial findings showing that local P. acnes proliferation causes upregulation of inflammatory markers and disk degeneration consistent with Modic changes (Aghazadeh et al., 2016; Dudli et al., 2016). There is now even first clinical evidence to suggest that bacterial infection of the intervertebral disk with P. acnes and/or Staphylococcus epidermidis may actually precede all other issues as the root cause of disk herniation and associated pathological changes (Rajasekaran et al., 2017).

Parkinson's disease (PD)

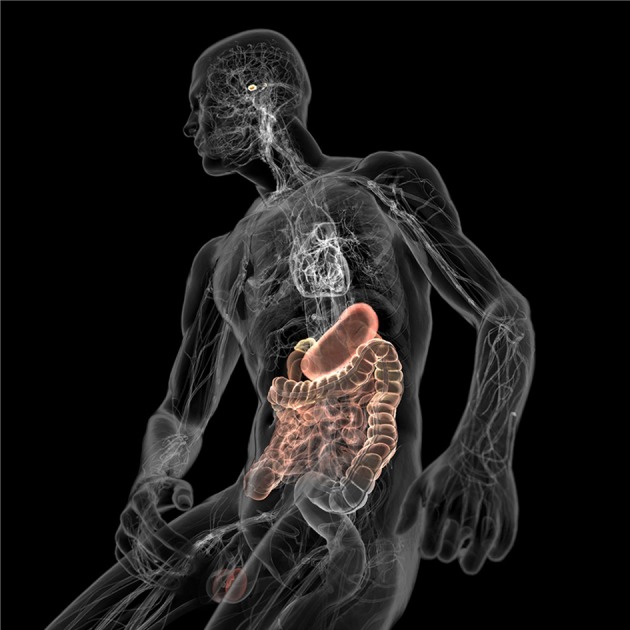

The degenerating brain is characterized by neural system damage that may be attributed to atypical aggregation and deposition of mutant or misfolded proteins (e.g., Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites) as clearly documented in idiopathic PD (Taylor et al., 2002). What is generally not appreciated is that the brain is also susceptible to invading pathogens ranging from viruses and bacteria to fungi. These pathogens, or more specifically their endogenous components and/or metabolites, can produce central neurological deficits ranging from subtle signs of dementia and dystonia, which result from chronic, recurrent infection (De Chiara et al., 2012; Bibi et al., 2014), to more severe motor neuron disease as for example observed with the human endogenous retrovirus K (Li et al., 2015). Thus, it is clear that humans have a tremendously heavy systemic burden of microbes (Potgieter et al., 2015; Spadoni et al., 2015) which may incidentally contribute to the pathology of progressive neurodegenerative diseases with atypical protein component. Certainly, this working hypothesis is gaining considerable support as cognitive, emotional or pathological behavior appear to be indirectly affected by the spatial and personal distribution of microbes acting through the gut-brain axis (Figure 5) (Collins et al., 2012; Dinan et al., 2013; Mayer et al., 2014; Burokas et al., 2015). Indeed, a recent case-control study demonstrated that microbial variation in the gastrointestinal tract, both between and within individuals; correspond most significantly to phenotypical variations in PD (Scheperjans et al., 2015; Vizcarra et al., 2015). Although the underlying mechanisms linking microbiota composition with differences in PD are not clear, the above finding might at least explain the high prevalence of gastrointestinal abnormalities seen in PD patients (Dobbs et al., 2016). Further linking the microbiota to PD severity, sigmoid mucosal biopsies and fecal material collected from PD patients showed the presence of opportunistic and pro-inflammatory bacterial species that often cause chronic constipation, irritable bowel syndrome and ulcerative colitis (Keshavarzian et al., 2015). Collectively, these initial results suggest that relationships between different microbial communities in the gut are a common comorbidity in PD, and that unique individual signatures of the gut ecosystem can reinforce classic motor impairments of PD.

Figure 5.

Schematic illustration of the gut-brain axis (colored) with the microbe-filled digestive system on one end and the brain with its homeostasis centers (hypothalamus and pituitary) on the other. Both are connected through the cardiovascular and autonomic nervous system including the vagus nerve (cranial nerve X) which could facilitate microbial transition into the central nervous system (CNS). Kindly with permission from Bryan Christie Design (http://bryanchristiedesign.com/).

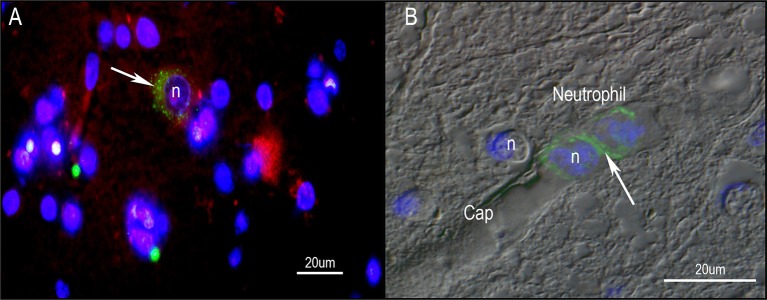

Against this background, the question to be asked is whether there is any evidence that P. acnes plays any role in the pathophysiology of PD. For this possibility to occur, two conditions must be met: (1) P. acnes infection must precede the occurrence of classic symptoms of the disease such as shaking, motor initiation and slowness of movement; and (2) P. acnes inoculation must sufficiently induce symptoms of PD and/or lead to the loss of dopamine projection neurons in the midbrain nucleus known as substantia nigra pars compacta. So far, our laboratory has detected clusters of P. acnes localized to neurons of the midbrain and nearby cortical structures of autopsied PD brains (Figure 6). This unexpected finding adds further credence of P. acnes indirectly contributing to local bouts of inflammation similar to those seen in sarcoidosis and BPH. An open question is the extent to which P. acnes can indirectly enhance certain pathological features of PD. As PD is a highly heterogeneous disorder, it is unlikely that one disease mechanism applies to all PD phenotypes. Nevertheless, it is intriguing to speculate that resident skin microbes could initiate or amplify PD progression through inflammatory and/or genetic predisposition factors.

Figure 6.

Immunohistochemistry of human PD midbrain tissue samples stained for P. acnes (green; A+B), neuronal microtubules (MAP2; red; A) and nuclei (DAPI; blue; A+B). Age-linked lipofuscin auto-fluorescence was extinguished with Sudan Black B. Presence of P. acnes (arrow) in the periplasmic space of a human neuron (A) between nucleus (n) and cytoskeleton; or neutrophil (B) with its characteristic multi-lobed nucleus inside a midbrain capillary (Cap). These findings are typical for PD and absent in most control sections. Retrograde movements along cranial nerves, trauma-induced micro-bleeds as well as the newly discovered glymphatic system represent potential microbial pathways into the CNS.

If P. acnes can gain access to dopamine cells in the midbrain, what is the most likely route of inoculation and infection? Although the skin is physically compartmentalized from the brain, cross-inoculation remains a risk factor. For example, the nares could potentially harbor pathogenic P. acnes strains which would then translocate to the brain parenchyma to hyper-activate local macrophages called microglia; a phenomenon that is a consistent feature of PD pathology (reviewed by Chao et al., 2014). Research into nosocomial infections demonstrate bacterial species as diverse as Pneumococcus sp. (Zwijnenburg et al., 2001) and Salmonella sp. (Bollen et al., 2008) roving readily along the olfactory nerve (cranial nerve 1; CN 1) and eventually into the olfactory bulb. Another potential route of entrance for harmful microbes or dangerous misfolded proteins is the vagus nerve (cranial nerve 10; CN 10). Indeed under some circumstances, misfolded aggregates in the form of Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites appear to migrate from the vagus nerve to the brain, providing further evidence for pathogenic bacteria in association with toxic proteins to potentially contribute to selective neuronal vulnerability (Holmqvist et al., 2014). Of interest, brain nuclei of CN 1 and CN 10 are among the first sites to preferentially show deposition of Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites during the course of PD progression (Braak et al., 2004). This particular observation not only highlights a likely route of entrance for bacteria into the brain, but also provides a potential mechanism for the observation that truncal vagotomy significantly decreases the PD risk (Svensson et al., 2015). The link between head trauma and PD (Harris et al., 2013; Jafari et al., 2013; Pearce et al., 2015), together with the notion of a diverse blood microbiome (Potgieter et al., 2015), implies a vast potential for pathogenic opportunism as traumatic breaches in the blood brain barrier occur. With the recent discovery of a brain lymphatic (glymphatic) system (Iliff et al., 2012; Hitscherich et al., 2016) another potential route of brain infection must be considered.

Taken together, there is preclinical and some clinical evidence to indirectly implicate P. acnes as an independent variable affecting PD incidence or severity. This evidence is complemented by reports associating a severe skin disorder, acne inversa, with Alzheimer's disease (Wang et al., 2010). From a therapeutic perspective, the possibility of P. acnes driving or amplifying core features of PD represents an important resource for antibiotic approaches to neurodegenerative diseases. And from a research perspective, it would be worthy to examine patients with skin disorders more closely for evidence of neuropathology with earlier onset and a more severe disease phenotype.

Future outlook

The review presented in this article outlines an unexpected dark side of P. acnes with respect to pathology. Intracellular persistence of P. acnes is implicated in diseases of the lungs and prostate gland and possibly the brain. This is a clear testimony for the pathogenicity of skin-derived bacteria in certain disease phenotypes. Further investigation will need to focus on several looming questions in P. acnes biology: (1) what are the crucial P. acnes interactions in disease susceptibility? (2) What are the mechanisms used by P. acnes to influence disease progression? (3) If certain populations of P. acnes can enhance susceptibility to disease severity, are there other configurations of P. acnes that are protective? (4) Proof of concept that P. acnes infection directly associates with disease pathology, or more specifically, does the study of concept show causation or just correlation? And finally (5) Can P. acnes-driven disease pathology be treated with conventional antibiotic therapy and diagnostic applications?

Author contributions

JL, KER, JC, KR, CH, AM, HB, and GT prepared the manuscript. JL and MS prepared the figures.

Funding

Intramural funding to JL was provided by NYIT College of Osteopathic Medicine.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Aghazadeh J., Salehpour F., Ziaeii E., Javanshir N., Samadi A., Sadeghi J., et al. (2016). Modic changes in the adjacent vertebrae due to disc material infection with Propionibacterium acnes in patients with lumbar disc herniation. Eur. Spine J. 10.1007/s00586-016-4887-4. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert H. B., Lambert P., Rollason J., Sorensen J. S., Worthington T., Pedersen M. B., et al. (2013). Does nuclear tissue infected with bacteria following disc herniations lead to Modic changes in the adjacent vertebrae? Eur. Spine J. 22, 690–696. 10.1007/s00586-013-2674-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexeyev O. A., Marklund I., Shannon B., Golovleva I., Olsson J., Andersson C., et al. (2007). Direct visualization of Propionibacterium acnes in prostate tissue by multicolor fluorescent in situ hybridization assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45, 3721–3728. 10.1128/JCM.01543-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae Y., Ito T., Iida T., Uchida K., Sekine M., Nakajima Y., et al. (2014). Intracellular Propionibacterium acnes infection in glandular epithelium and stromal macrophages of the prostate with or without cancer. PLoS ONE 9:e90324 10.1371/journal.pone.0090324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnard E., Liu J., Yankova E., Cavalcanti S. M., Magalhães M., Li H., et al. (2016). Strains of the Propionibacterium acnes type III lineage are associated with the skin condition progressive macular hypomelanosis. Sci. Rep. 6:31968. 10.1038/srep31968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibi F., Yasir M., Sohrab S. S., Azhar E. I., Al-Qahtani M. H., Abuzenadah A. M., et al. (2014). Link between chronic bacterial inflammation and Alzheimer disease. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets. 13, 1140–1147. 10.2174/1871527313666140917115741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bojar R. A., Holland K. T. (2004). Acne and Propionibacterium acnes. Clin. Dermatol. 22, 375–379. 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2004.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen W. S., Gunn B. M., Mo H., Lay M. K., Curtiss R., III. (2008). Presence of wild-type and attenuated Salmonella enterica strains in brain tissues following inoculation of mice by different routes. Infect. Immun. 76, 3268–3272. 10.1128/IAI.00244-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braak H., Ghebremedhin E., Rüb U., Bratzke H., Del Tredici K. (2004). Stages in the development of Parkinson's disease-related pathology. Cell Tissue Res. 318, 121–134. 10.1007/s00441-004-0956-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burokas A., Moloney R. D., Dinan T. G., Cryan J. F. (2015). Microbiota regulation of the Mammalian gut-brain axis. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 91, 1–62. 10.1016/bs.aambs.2015.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamaillard M., Girardin S. E., Viala J., Philpott D. J. (2003). Nods, Nalps and Naip: intracellular regulators of bacterial-induced inflammation. Cell. Microbiol. 5, 581–592. 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2003.00304.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao Y., Wong S. C., Tan E. K. (2014). Evidence of inflammatory system involvement in Parkinson's disease. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014:308654. 10.1155/2014/308654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cogen A. L., Nizet V., Gallo R. L. (2008). Skin microbiota: a source of disease or defence? Br. J. Dermatol. 158, 442–455. 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08437.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen R. J., Shannon B. A., McNeal J. E., Shannon T., Garrett K. L. (2005). Propionibacterium acnes associated with inflammation in radical prostatectomy specimens: a possible link to cancer evolution? J. Urol. 173, 1969–1974. 10.1097/01.ju.0000158161.15277.78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins S. M., Surette M., Bercik P. (2012). The interplay between the intestinal microbiota and the brain. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 10, 735–742. 10.1038/nrmicro2876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidsson S., Mölling P., Rider J. R., Unemo M., Karlsson M. G., Carlsson J., et al. (2016). Frequency and typing of Propionibacterium acnes in prostate tissue obtained from men with and without prostate cancer. Infect. Agent Cancer 11:26. Erratum in: Infect. Agent Cancer. (2016) 11:36. 10.1186/s13027-016-0074-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Brouwer B., Veltkamp M., Wauters C. A., Grutters J. C., Janssen R. (2015). Propionibacterium acnes isolated from lymph nodes of patients with sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 32, 271–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Chiara G., Marcocci M. E., Sgarbanti R., Civitelli L., Ripoli C., Piacentini R., et al. (2012). Infectious agents and neurodegeneration. Mol. Neurobiol. 46, 614–638. 10.1007/s12035-012-8320-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Marzo A. M., Marchi V. L., Epstein J. I., Nelson W. G. (1999). Proliferative inflammatory atrophy of the prostate: implications for prostatic carcinogenesis. Am. J. Pathol. 155, 1985–1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinan T. G., Stanton C., Cryan J. F. (2013). Psychobiotics: a novel class of psychotropic. Biol. Psychiatry 74, 720–726. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobbs S. M., Dobbs R. J., Weller C., Charlett A., Augustin A., Taylor D., et al. (2016). Peripheral aetiopathogenic drivers and mediators of Parkinson's disease and co-morbidities: role of gastrointestinal microbiota. J. Neurovirol. 22, 22–32. 10.1007/s13365-015-0357-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drott J. B., Alexeyev O., Bergström P., Elgh F., Olsson J. (2010). Propionibacterium acnes infection induces upregulation of inflammatory genes and cytokine secretion in prostate epithelial cells. BMC Microbiol. 10:126. 10.1186/1471-2180-10-126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudli S., Liebenberg E., Magnitsky S., Miller S., Demir-Deviren S., Lotz J. C. (2016). Propionibacterium acnes infected intervertebral discs cause vertebral bone marrow lesions consistent with Modic changes. J. Orthop. Res. 34, 1447–1455. 10.1002/jor.23265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eishi Y. (2013). Etiologic link between sarcoidosis and Propionibacterium acnes. Respir. Investig. 51, 56–68. 10.1016/j.resinv.2013.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eishi Y., Suga M., Ishige I., Kobayashi D., Yamada T., Takemura T., et al. (2002). Quantitative analysis of mycobacterial and propionibacterial DNA in lymph nodes of Japanese and European patients with sarcoidosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40, 198–204. 10.1128/JCM.40.1.198-204.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fassi-Fehri L., Mak T. N., Laube B., Brinkmann V., Ogilvie L. A., Mollenkopf H., et al. (2011). Prevalence of Propionibacterium acnes in diseased prostates and its inflammatory and transforming activity on prostate epithelial cells. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 301, 69–78. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2010.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findley K., Grice E. A. (2014). The skin microbiome: a focus on pathogens and their association with skin disease. PLoS Pathog. 10:e1004436. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funke G., Renaud F. N., Freney J., Riegel P. (1997). Multicenter evaluation of the updated and extended API (RAPID) Coryne database 2.0. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35, 3122–3126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gambara G., De Cesaris P., De Nunzio C., Ziparo E., Tubaro A., Filippini A., et al. (2013). Toll-like receptors in prostate infection and cancer between bench and bedside. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 17, 713–722. 10.1111/jcmm.12055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham G. M., Farrar M. D., Cruse-Sawyer J. E., Holland K. T., Ingham E. (2004). Proinflammatory cytokine production by human keratinocytes stimulated with Propionibacterium acnes and P. acnes GroEL. Br. J. Dermatol. 150, 421–428. 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2004.05762.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grice E. A., Kong H. H., Conlan S., Deming C. B., Davis J., Young A. C., et al. (2009). Topographical and temporal diversity of the human skin microbiome. Science 324, 1190–1192. 10.1126/science.1171700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grice E. A., Segre J. A. (2011). The skin microbiome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9, 244–253. Erratum in: Nat. Rev. Microbiol. (2011) 9:626. 10.1038/nrmicro2537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris A. E., Hennicke C., Byers K., Welch W. C. (2005). Postoperative discitis due to Propionibacterium acnes: a case report and review of the literature. Surg Neurol. 63, 538–541; discussion: 541. 10.1016/j.surneu.2004.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris M. A., Shen H., Marion S. A., Tsui J. K., Teschke K. (2013). Head injuries and Parkinson's disease in a case-control study. Occup. Environ. Med. 70, 839–844. 10.1136/oemed-2013-101444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hitscherich K., Smith K., Cuoco J. A., Ruvolo K. E., Mancini J. D., Leheste J. R., et al. (2016). The glymphatic-lymphatic continuum: opportunities for osteopathic manipulative medicine. J. Am. Osteopath. Assoc. 116, 170–177. 10.7556/jaoa.2016.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochreiter W. W., Nadler R. B., Koch A. E., Campbell P. L., Ludwig M., Weidner W., et al. (2000). Evaluation of the cytokines interleukin 8 and epithelial neutrophil activating peptide 78 as indicators of inflammation in prostatic secretions. Urology 56, 1025–1029. 10.1016/S0090-4295(00)00844-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmqvist S., Chutna O., Bousset L., Aldrin-Kirk P., Li W., Björklund T., et al. (2014). Direct evidence of Parkinson pathology spread from the gastrointestinal tract to the brain in rats. Acta Neuropathol. 128, 805–820. 10.1007/s00401-014-1343-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iliff J. J., Wang M., Liao Y., Plogg B. A., Peng W., Gundersen G. A., et al. (2012). A paravascular pathway facilitates CSF flow through the brain parenchyma and the clearance of interstitial solutes, including amyloid β. Sci. Transl. Med. 4, 147ra111. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inohara N., Nuñez G. (2001). The NOD: a signaling module that regulates apoptosis and host defense against pathogens. Oncogene 20, 6473–6481. 10.1038/sj.onc.1204787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jafari S., Etminan M., Aminzadeh F., Samii A. (2013). Head injury and risk of Parkinson disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mov. Disord. 28, 1222–1229. 10.1002/mds.25458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen I., Seed P. C. (2012). How to make it in the urinary tract: a tutorial by Escherichia coli. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002907. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshavarzian A., Green S. J., Engen P. A., Voigt R. M., Naqib A., Forsyth C. B., et al. (2015). Colonic bacterial composition in Parkinson's disease. Mov. Disord. 30, 1351–1360. 10.1002/mds.26307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Ochoa M. T., Krutzik S. R., Takeuchi O., Uematsu S., Legaspi A. J., et al. (2002). Activation of toll-like receptor 2 in acne triggers inflammatory cytokine responses. J. Immunol. 169, 1535–1541. 10.4049/jimmunol.169.3.1535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurokawa I., Danby F. W., Ju Q., Wang X., Xiang L. F., Xia L., et al. (2009). New developments in our understanding of acne pathogenesis and treatment. Exp. Dermatol. 18, 821–832. 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2009.00890.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S. E., Kim J. M., Jeong S. K., Jeon J. E., Yoon H. J., Jeong M. K., et al. (2010). Protease-activated receptor-2 mediates the expression of inflammatory cytokines, antimicrobial peptides, and matrix metalloproteinases in keratinocytes in response to Propionibacterium acnes. Arch Dermatol. Res. 302, 745–756. 10.1007/s00403-010-1074-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Lee M. H., Henderson L., Tyagi R., Bachani M., Steiner J., et al. (2015). Human endogenous retrovirus-K contributes to motor neuron disease. Sci. Transl. Med. 7, 307ra153. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aac8201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak T. N., Fischer N., Laube B., Brinkmann V., Metruccio M. M., Sfanos K. S., et al. (2012). Propionibacterium acnes host cell tropism contributes to vimentin-mediated invasion and induction of inflammation. Cell. Microbiol. 14, 1720–1733. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2012.01833.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak T. N., Yu S. H., De Marzo A. M., Brüggemann H., Sfanos K. S. (2013). Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) analysis of Propionibacterium acnes isolates from radical prostatectomy specimens. Prostate 73, 770–777. 10.1002/pros.22621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer E. A., Knight R., Mazmanian S. K., Cryan J. F., Tillisch K. (2014). Gut microbes and the brain: paradigm shift in neuroscience. J. Neurosci. 34, 15490–15496. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3299-14.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechergui Y. B., Ben Jemaa A., Mezigh C., Fraile B., Ben Rais N., Paniagua R., et al. (2009). The profile of prostate epithelial cytokines and its impact on sera prostate specific antigen levels. Inflammation 32, 202–210. 10.1007/s10753-009-9121-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menschikowski M., Hagelgans A., Fuessel S., Mareninova O. A., Asatryan L., Wirth M. P., et al. (2013). Serum amyloid A, phospholipase A2-IIA and C-reactive protein as inflammatory biomarkers for prostate diseases. Inflamm. Res. 62, 1063–1072. 10.1007/s00011-013-0665-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira L. O., Zamboni D. (2012). S. NOD1 and NOD2 Signaling in infection and inflammation. Front. Immunol. 3:328 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy I., Pivarcsi A., Kis K., Koreck A., Bodai L., McDowell A., et al. (2006). Propionibacterium acnes and lipopolysaccharide induce the expression of antimicrobial peptides and proinflammatory cytokines/chemokines in human sebocytes. Microbes Infect. 8, 2195–2205. 10.1016/j.micinf.2006.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson W. G., De Marzo A. M., DeWeese T. L., Isaacs W. B. (2004). The role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of prostate cancer. J. Urol. 172(5 Pt 2):S6–S11; discussion: S11–S2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni X., Meng H., Zhou F., Yu H., Xiang J., Shen S. (2016). Effect of hypertension on bacteria composition of prostate biopsy in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostate cancer in PSA grey-zone. Biomed. Rep. 4, 765–769. 10.3892/br.2016.655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh J., Byrd A. L., Deming C., Conlan S., NISC Comparative Sequencing, Program. Kong H. H., et al. (2014). Biogeography and individuality shape function in the human skin metagenome. Nature 514, 59–64. 10.1038/nature13786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson J., Drott J. B., Laurantzon L., Laurantzon O., Bergh A., Elgh F. (2012). Chronic prostatic infection and inflammation by Propionibacterium acnes in a rat prostate infection model. PLoS ONE 7:e51434. 10.1371/journal.pone.0051434 Erratum in: PLoS ONE (2013) 8. 10.1371/annotation/2160e616-aa79-4097-96ab-e143d2a4d136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce N., Gallo V., McElvenny D. (2015). Head trauma in sport and neurodegenerative disease: an issue whose time has come? Neurobiol. Aging 36, 1383–1389. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.12.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry A., Lambert P. (2011). Propionibacterium acnes: infection beyond the skin. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 9, 1149–1156. 10.1586/eri.11.137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portillo M. E., Corvec S., Borens O., Trampuz A. (2013). Propionibacterium acnes: an underestimated pathogen in implant-associated infections. Biomed. Res Int. 2013:804391. 10.1155/2013/804391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potgieter M., Bester J., Kell D. B., Pretorius E. (2015). The dormant blood microbiome in chronic, inflammatory diseases. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 39, 567–591. 10.1093/femsre/fuv013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajasekaran S., Tangavel C., Aiyer S. N., Nayagam S. M., Raveendran M., Demonte N. L., et al. (2017). Is infection the possible initiator of disc disease? An insight from proteomic analysis. Eur. Spine J. 10.1007/s00586-017-4972-3. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanford J. A., Zhang L., Williams M. R., Gangoiti J. A., Huang C., Gallo R. L. (2016). Inhibition of HDAC8 and HDAC9 by microbial short-chain fatty acids breaks immune tolerance of the epidermis to TLR ligands. Sci. Immunol. 1. 10.1126/sciimmunol.aah4609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharschmidt T. C., Vasquez K. S., Truong H. A., Gearty S. V., Pauli M. L., Nosbaum A., et al. (2015). A wave of regulatory t cells into neonatal skin mediates tolerance to commensal microbes. Immunity 43, 1011–1021. 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.10.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheperjans F., Aho V., Pereira P. A., Koskinen K., Paulin L., Pekkonen E., et al. (2015). Gut microbiota are related to Parkinson's disease and clinical phenotype. Mov. Disord. 30, 350–358. 10.1002/mds.26069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schupp J. C., Tchaptchet S., Lützen N., Engelhard P., Müller-Quernheim J., Freudenberg M. A., et al. (2015). Immune response to Propionibacterium acnes in patients with sarcoidosis–in vivo and in vitro. BMC Pulm Med. 15:75. 10.1186/s12890-015-0070-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sfanos K. S., Hempel H. A., De Marzo A. M. (2014). The role of inflammation in prostate cancer. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 816, 153–181. 10.1007/978-3-0348-0837-8_7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sfanos K. S., Isaacs W. B., De Marzo A. M. (2013). Infections and inflammation in prostate cancer. Am. J. Clin. Exp. Urol. 1, 3–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sfanos K. S., Sauvageot J., Fedor H. L., Dick J. D., De Marzo A. M., Isaacs W. B. (2008). A molecular analysis of prokaryotic and viral DNA sequences in prostate tissue from patients with prostate cancer indicates the presence of multiple and diverse microorganisms. Prostate 68, 306–320. 10.1002/pros.20680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinohara D. B., Vaghasia A. M., Yu S. H., Mak T. N., Brüggemann H., Nelson W. G., et al. (2013). A mouse model of chronic prostatic inflammation using a human prostate cancer-derived isolate of Propionibacterium acnes. Prostate 73, 1007–1015. 10.1002/pros.22648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spadoni I., Zagato E., Bertocchi A., Paolinelli R., Hot E., Di Sabatino A., et al. (2015). A gut-vascular barrier controls the systemic dissemination of bacteria. Science 350, 830–834. 10.1126/science.aad0135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson E., Horváth-Puh,ó E., Thomsen R. W., Djurhuus J. C., Pedersen L., Borghammer P., et al. (2015). Vagotomy and subsequent risk of Parkinson's disease. Ann. Neurol. 78, 522–529. 10.1002/ana.24448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanabe T., Ishige I., Suzuki Y., Aita Y., Furukawa A., Ishige Y., et al. (2006). Sarcoidosis and NOD1 variation with impaired recognition of intracellular Propionibacterium acnes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1762, 794–801. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2006.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor J. P., Hardy J., Fischbeck K. H. (2002). Toxic proteins in neurodegenerative disease. Science 296, 1991–1995. 10.1126/science.1067122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai H. H., Lee W. R., Wang P. H., Cheng K. T., Chen Y. C., Shen S. C. (2013). Propionibacterium acnes-induced iNOS and COX-2 protein expression via ROS-dependent NF-κB and AP-1 activation in macrophages. J. Dermatol. Sci. 69, 122–131. 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2012.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uçkay I., Dinh A., Vauthey L., Asseray N., Passuti N., Rottman M., et al. (2010). Spondylodiscitis due to Propionibacterium acnes: report of twenty-nine cases and a review of the literature. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 16, 353–358. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.02801.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urquhart D. M., Zheng Y., Cheng A. C., Rosenfeld J. V., Chan P., Liew S., et al. (2015). Could low grade bacterial infection contribute to low back pain? A systematic review. BMC Med. 13:13. 10.1186/s12916-015-0267-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vizcarra J. A., Wilson-Perez H. E., Espay A. J. (2015). The power in numbers: gut microbiota in Parkinson's disease. Mov. Disord. 30, 296–298. 10.1002/mds.26116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang B., Yang W., Wen W., Sun J., Su B., Liu B., et al. (2010). Gamma-secretase gene mutations in familial acne inversa. Science 330, 1065. 10.1126/science.1196284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner J. L., Escolero S. G., Hewlett J. T., Mak T. N., Williams B. P., Eishi Y., et al. (2017). Induction of pulmonary granuloma formation by Propionibacterium acnes is regulated by MyD88 and Nox2. Am. J. Respir Cell. Mol. Biol. 56, 121–130. 10.1165/rcmb.2016-0035OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada T., Eishi Y., Ikeda S., Ishige I., Suzuki T., Takemura T., et al. (2002). In situ localization of Propionibacterium acnes DNA in lymph nodes from sarcoidosis patients by signal amplification with catalysed reporter deposition. J. Pathol. 198, 541–547. 10.1002/path.1243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H., Meng H., Zhou F., Ni X., Shen S., Das U. N. (2015). Urinary microbiota in patients with prostate cancer and benign prostatic hyperplasia. Arch. Med. Sci. 11, 385–394. 10.5114/aoms.2015.50970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y., Champer J., Agak G. W., Kao S., Modlin R. L., Kim J. (2016). Different Propionibacterium acnes phylotypes induce distinct immune responses and express unique surface and secreted proteomes. J. Invest. Dermatol. 136, 2221–2228. 10.1016/j.jid.2016.06.615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z., Chen Z., Zheng Y., Cao P., Liang Y., Zhang X., et al. (2015). Relationship between annular tear and presence of Propionibacterium acnes in lumbar intervertebral disc. Eur. Spine J. 24, 2496–2502. 10.1007/s00586-015-4180-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwijnenburg P. J., van der Poll T., Florquin S., van Deventer S. J., Roord J. J., van Furth A. M. (2001). Experimental pneumococcal meningitis in mice: a model of intranasal infection. J. Infect Dis. 183, 1143–1146. 10.1086/319271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]