Highlights

-

•

Gastrointestinal cytomegalovirus infections can occur in immunocompetent patients.

-

•

Diagnosis relies on histopathologic examination of endoscopic biopsy specimen.

-

•

Early recognition and antiviral treatment are important to patient outcome.

-

•

Cytomegalovirus duodenitis has significant potential to be life-threatening.

Keywords: Cytomegalovirus, Enteritis, Duodenitis, Duodenum, Immunocompetent, Gastrointestinal bleed

Abstract

Introduction

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is known to be opportunistic in immunocompromised patients. However, there have been emerging cases of severe CMV infections found in immunocompetent patients. Gastrointestinal (GI) CMV disease is the most common manifestation affecting immunocompetent patients, with duodenal involvement being exceedingly rare. Presented is a case of an immunocompetent patient with life-threatening bleeding caused by CMV duodenitis, requiring surgical intervention.

Presentation of case

A 60-year-old male with history of disseminated Methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) bacteremia and aortic valve infective endocarditis, presented with life-threatening upper GI hemorrhage. Endoscopy revealed ulcerations, with associated generalized mucosal bleeding in the duodenum. After repeated endoscopic therapies and failed interventional-radiology arterial embolization, the patient required a duodenectomy and associated total pancreatectomy, to control the duodenal hemorrhage. Pathologic review of the surgical specimen demonstrated CMV duodenitis. Systemic ganciclovir was utilized postoperatively.

Discussion

GI CMV infections should be on the differential diagnosis of immunocompetent patients presenting with uncontrollable GI bleeding, especially in critically ill patients due to transiently suppressed immunity. Endoscopic and histopathological examinations are often required for diagnosis. Ganciclovir is first-line treatment. Surgical intervention may be considered if there is recurrent bleeding and CMV duodenitis is suspected because of high potential for bleeding-associated mortality.

Conclusion

Presented is a rare case of life-threatening GI hemorrhage caused by CMV duodenitis in an immunocompetent patient. The patient failed endoscopic and interventional-radiology treatment options, and ultimately stabilized after surgical intervention.

1. Introduction

Cytomegalovirus (CMV), part of Herpesviridae genus, is a common virus, with positive serology found in more than two-thirds of the population [1]. Initial infection is self-limited in healthy individuals. However, the virus remains latent in immunocompetent individuals, while reactivation may occur in the setting of immunosuppression. CMV is known to be opportunistic in immunocompromised individuals with HIV infection, organ transplantation, immunosuppressive chemotherapy, and corticosteroid therapy [2]. In immunocompromised patient, CMV infections can have an effect on the retina, respiratory system, central nervous system and gastrointestinal (GI) tract [3]. However, over the past decade, there have been emerging cases of severe CMV infections in immunocompetent individuals, with the GI tract found to be the most frequently affected site [4]. In both immunocompromised and immunocompetent individuals, GI CMV presents most commonly in the form of CMV colitis [2].

The majority of CMV enteritis cases have been reported in the ileum, including severe complications leading to perforation and ischemia [2], [3], [5]. CMV duodenitis is exceedingly rare [6]. Presented is a case report of CMV duodenitis that manifested with life-threatening hemorrhage in an immunocompetent patient.

2. Presentation of case

A 60-year-old Honduran man initially presented to hospital with acute delirium. Past medical history included alcohol abuse and hypertension, treated with hydrochlorothiazide. Upon admission, the patient was found to have Methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) bacteremia with aortic valvular endocarditis and disseminated septic emboli. Investigations revealed wide spread infection, including MSSA meningitis, C6-7 osteomyelitis, and spinal and sternoclavicular joint abscesses. Multiple septic emboli infarcts were identified in the brain, liver, spleen and kidneys. The patient ultimately required an aortic valve replacement.

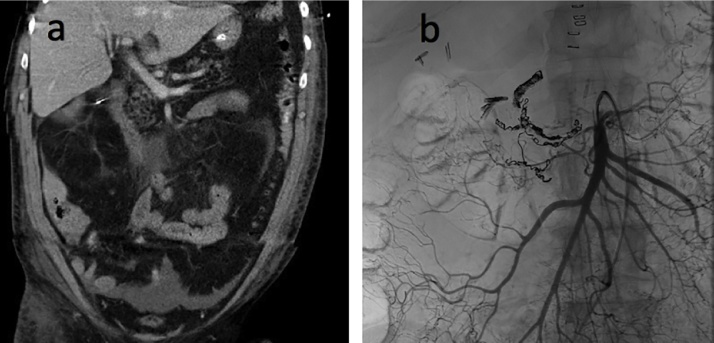

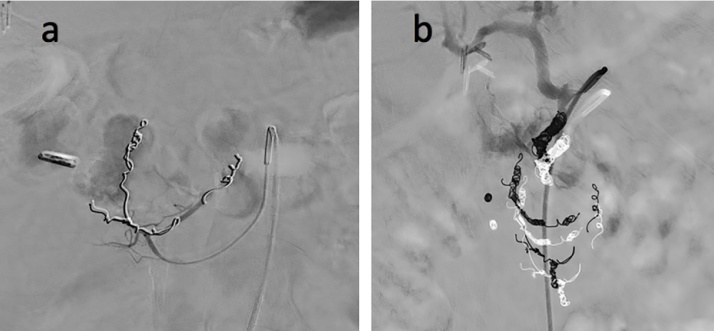

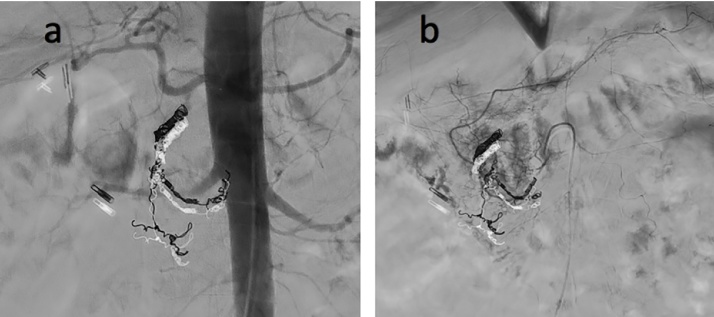

While in hospital, the patient developed significant upper GI bleeding, requiring aggressive blood transfusions. Three duodenal ulcers with visible vessels were identified on endoscopy. General surgery was initially consulted, but less-invasive therapies were favored at the time due to the patient’s severe comorbidities. The duodenal ulcers were found to be actively bleeding on five subsequent endoscopies, with attempts to halt the bleeding through epinephrine injection, BICAP cauterization, endoclipping of vessels, hemospray with procoagulant, and argon plasma coagulation. IR embolization of the gastroduodenal artery and multiple branches of the superior and inferior pancreaticoduodenal arteries also failed to control bleeding (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3 ). The patient continued to hemorrhage, requiring daily transfusions to maintain hemodynamic stability, totaling more than 95 units of packed red cells during the admission in the intensive care unit.

Fig. 1.

a) CT abdomen in coronal view shows thickened duodenal wall with surrounding edema, consistent with duodenitis. Pancreatic head appears normal. b) Mesenteric angiogram shows superior mesenteric artery being filled with contrast. There is coil embolization of the inferior pancreaticoduodenal arcade and gastroduodenal artery. Multiple endoscopic clips are seen in the duodenum. Cholecystectomy surgical clips are additionally seen in the right upper quadrant.

Fig. 2.

a) Mesenteric angiogram shows one endoscopic clip in the right upper quadrant and multiple coils in branches of anterior and posterior inferior pancreaticoduodenal arteries, as well as its collateral artery. Contrast blush is seen in the duodenum. b) Mesenteric angiogram shows gastroduodenal artery embolized with multiple coils at proximal insert of gastroepiploic artery. Contrast blush is again seen, representing active extravasation from gastroduodenal artery.

Fig. 3.

a) Follow-up abdominal aortogram shows contrast blush in the duodenum despite coil embolization of the gastroduodenal artery. b) Follow-up mesenteric angiogram shows filling of pancreaticoduodenal arcades despite coil embolization of some branches. Active extravasation from several small branches continues to be present in proximal duodenum adjacent to endoscopic clip.

The last endoscopy revealed a generalized mucosal bleed throughout the duodenum. With no further options available within GI or IR’s scopes of practice, Hepato-Pancreatico-Biliary surgery was urgently consulted. Duodenal resection, which included a Whipple procedure, was recommended as treatment for the unrelenting duodenal hemorrhage. However, given the patient's critical condition and ongoing hemorrhage, it was felt that the patient would be at high risk (>30%) for pancreaticojejunostomy anastomotic leak and significant mortality. Therefore, duodenal resection with total pancreatectomy and splenectomy was performed to control the hemorrhage and remove the risk of pancreaticojejunostomy leak. Multiple aberrant blood vessels extending into the duodenum were successfully controlled at the time of surgery. The patient was critically ill throughout the procedure, and was transferred to the ICU after the resection of the duodenum and pancreas. The patient returned to the operating room in stages to complete the gastrojejunostomy and hepaticojejunostomy.

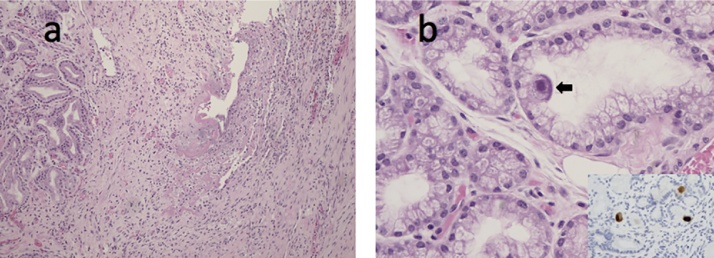

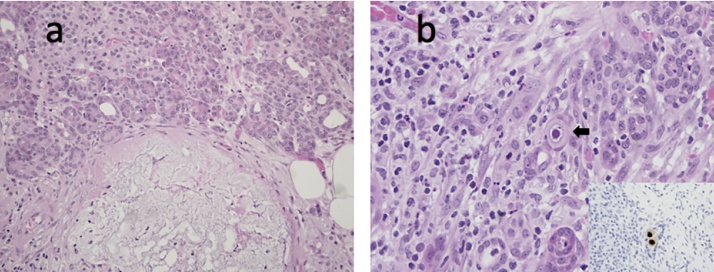

Gross examination of the resected specimen revealed a flattened, congested, and focally ulcerated duodenal mucosa. Histologic sections from an ulcer revealed viral cytopathic changes in keeping with CMV (Fig. 4a and b). The surrounding surface duodenal mucosa had extensive autolysis; no vasculitis or intravascular thrombi were identified. Sections from the pancreas showed patchy panlobular coagulative necrosis (Fig. 5a). Non-occlusive thrombi were seen within few muscularized arteries. Notably, ductal epithelial cells had viral cytopathic changes, which were also in keeping with CMV (Fig. 5b). Immunohistochemical stains for CMV were positive in both the duodenum and pancreas (see insets of Figs. 4 b and 5 b). The stomach had mild reactive gastropathy and were negative for Helicobacter gastritis.

Fig. 4.

a) Duodenal ulcer abutting Brunner’s glands (haematoxylin and eosin; 100X). b) Mucin-secreting epithelial cell in a Brunner’s gland with viral cytopathic changes in keeping with CMV infection including an eosinophilic intranuclear inclusion and amphophilic finely granular intracytoplasmic inclusions (arrow, haematoxylin and eosin; 400X). Inset: CMV immunostain highlights both intranuclear and cytoplasmic inclusions in three epithelial cells (400X).

Fig. 5.

a) Pancreas with patchy severe necrotizing acute pancreatitis. Note the Islet of Langerhans in the upper left hand corner abutting pancreatic acinar cells (haematoxylin and eosin; 200X). b) An epithelial cell with an eosinophilic intranuclear viral inclusion (arrow) in keeping with CMV (haematoxylin and eosin; 400X). Inset: CMV immunostain highlights intranuclear inclusions in two epithelial cells (400X).

Serologic studies revealed nonreactive CMV IgM antibodies and reactive CMV IgG antibodies. DNA quantitative PCR for CMV was negative. HIV, hepatitis B and hepatitis C immunologic assays were normal.

3. Outcome and follow-up

Post-duodenal resection, the patient remained hemodynamically stable, requiring no additional blood transfusions. Infectious disease initiated intravenous ganciclovir, 5 mg/kg twice daily then transitioned to oral valganciclovir 900 mg BID once tolerating an oral diet for a total course of three weeks. While on antiviral medications, the completed blood count and creatinine were closely monitored for evidence of pancytopenia and renal dysfunction. CMV DNA PCR was monitored for any sign of CMV reactivation.

4. Discussion

CMV infections commonly occur in the GI tract, while localized duodenal infection is very rare. A 2011 study of CMV infection in the upper GI tract, found the stomach to be the most common site of involvement and only one out of thirty cases involved the duodenum [6]. Literature review identified four case reports of CMV duodenitis [7], [8], [9], [10], where all four cases involved immunocompromised patients. Presented here is an atypical case of CMV duodenitis causing life-threatening hemorrhage in an immunocompetent individual, with no history of immunosuppressive treatments or infections. However, this patient did present with critical illness from his disseminated MSSA bacteremia and infective endocarditis, which could have caused a transient depression in immunity. ICU admission, use of antibiotics, and use of antacids including H2 blockers and PPIs, are found to be risk factors for CMV reactivation in immunocompetent patients [11]. A recent review of reactivation of CMV infection in immunocompetent critically-ill patients found that CMV colitis was the most prevalent manifestation, carrying a 71% in-hospital mortality rate despite specific treatment with ganciclovir [11]. The most frequent symptom was GI bleeding, as seen with this patient [12]. Although severe GI CMV is uncommon in immunocompetent hosts, there can be a significant mortality rate associated and thus CMV reactivation should be considered in the differential diagnosis of uncontrolled GI bleeding, especially in the setting of a critically-ill patient.

Diagnosis of gastrointestinal CMV infection often requires endoscopy with biopsies. CMV is difficult to identify based on endoscopic appearance alone because presentations are nonspecific. Primary findings include ulcerations, erosions, and mucosal hemorrhage [8]. The diagnostic gold standard for CMV infection is histopathological examination of endoscopic biopsy or surgical specimen. Hematoxylin-eosin stains typically show intranuclear “owl-eye” or Cowdry type A inclusion bodies in stromal and endothelial cells, which are hypertrophic cells containing eosinophilic intranuclear viral inclusions [2]. Specimen may also be examined with immunochemical staining for CMV antigen [9]. Serologic detection of CMV IgM and IgG are often not helpful in identifying active disease but may determine recent or past exposure. Virologic testing options include CMV DNA PCR and CMV blood antigenemia assays. However, it’s not uncommon to have isolated gastrointestinal CMV disease without detectable viremia, as in the case of this patient [13]. Therefore, the roles of serologic and virologic testing appears to be limited in the diagnosis of GI-restricted CMV disease.

First-line treatment for gastrointestinal CMV disease is intravenous ganciclovir 5 mg/kg BID or oral valganciclovir 900 mg BID [2]. There is significant toxicity with ganciclovir, including headaches, transaminitis, fever, rash, and myelosuppression in the form of pancytopenia [2]. An alternative is foscarnet, which can be used as initial treatment or in ganciclovir failure [14]. The role of treatment is unclear in immunocompetent hosts as some will resolve disease without any treatment. There are limited data on duration of therapy for immunocompetent hosts, but studies have documented response in two to three weeks [15], [16]. Prolonged treatment longer than 21 days is generally not required [11].

Unfortunately, gastrointestinal CMV disease is not always readily diagnosed, especially in an immunocompetent patient as suspicion may be low. In the case of CMV duodenitis, there does appear to be a significant potential for mortality. Here we presented an immunocompetent patient with CMV duodenitis that manifested with ongoing hemorrhage, failing multiple attempts at non-surgical treatments, and ultimately requiring surgical intervention. This is the first known case report of life-threatening hemorrhage from CMV duodenitis managed successfully with surgery. Among the four CMV duodenitis case reports found during literature review, three manifested with life-threatening bleeding, only one patient survived [7], [8], [9], [10]. In the surviving case, CMV was identified emergently on histopathologic examination of endoscopic biopsy [9]. The patient was started on ganciclovir immediately and stabilized after 4 days of therapy [9]. Early recognition and antiviral treatment of CMV duodenitis are important to patient outcome. As seen in our case, surgical intervention is warranted if noninvasive treatments fail. Interestingly, acute necrotizing pancreatitis secondary to arterial embolizations, was found in our patient. Surface mucosa of the duodenum was also found to be autolysed by pancreatic juice. This likely exacerbated the duodenal bleed and would have lead to further complications if surgical intervention was delayed.

5. Conclusion

GI CMV infections should be on the differential diagnosis of immunocompetent patients presenting with recurrent GI bleeding, especially in critically ill patients due to transiently suppressed immunity. Diagnosis relies on histopathologic examination of endoscopic biopsy specimen. Early recognition and antiviral treatment are important to patient outcome. CMV duodenitis has significant potential to be life-threatening. If failing noninvasive treatments, surgical intervention may be indicated.

Conflicts of interest

None to declare.

Funding sources

None.

Ethical approval

Not applicable for case reports as per journal policy.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and the accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author contributions

(1) Lucy Shen: drafting of the article, critical revision of the article for important intellectual and clinical content; (2) David Youssef: drafting of the article, critical revision of the article for important intellectual and clinical content; (3) Suzan Abu-Abed: image creation, critical revision of the article for important intellectual and clinical content; (4) Sangita K. Malhotra: critical revision of the article for important intellectual and clinical content; (5) Kenneth Atkinson: critical revision of the article for important intellectual and clinical content; (6) Elena Vikis: critical revision of the article for important intellectual and clinical content; (7) George Melich: critical revision of the article for important intellectual and clinical content, final approval of the version to be submitted; (8) Shawn MacKenzie: drafting of the article, critical revision of the article for important intellectual and clinical content, final approval of the version to be submitted.

Registration of research studies

Not applicable.

Guarantor

Shawn MacKenzie, M.D., will act as guarantor of this work.

References

- 1.Kalil A.C., Florescu D.F. Prevalence and mortality associated with cytomegalovirus infection in nonimmunosuppressed patients in the intensive care unit. Crit. Care Med. 2009;37(8):2350–2358. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181a3aa43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.You D.M., Johnson M.D. Cytomegalovirus infection and the gastrointestinal tract. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2012;14(4):334–342. doi: 10.1007/s11894-012-0266-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Michalopoulos N., Triantafillopoulou K., Beretouli E., Laskou S., Papavramidis T.S., Pliakos I. Small bowel perforation due to CMV enteritis infection in an HIV-positive patient. BMC Res. Notes. 2013;6:45. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-6-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rafailidis P.I., Mourtzoukou E.G., Varbobitis I.C., Falagas M.E. Severe cytomegalovirus infection in apparently immunocompetent patients: a systematic review. Virol. J. 2008;5:47. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-5-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Naseem Z., Hendahewa R., Mustaev M., Premaratne G. Cytomegalovirus enteritis with ischemia in an immunocompetent patient: a rare case report. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2015;15:146–148. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2015.08.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reggiani Bonetti L., Losi L., Di Gregorio C., Bertani A., Merighi A., Bettelli S. Cytomegalovirus infection of the upper gastrointestinal tract: a clinical and pathological study of 30 cases. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2011;46(10):1228–1235. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2011.594083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chao H.C., Yu W.L. Cytomegalovirus-infected duodenal ulcer with severe recurrent bleeding. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2016;115(8):682–683. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2016.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Makker J., Bajantri B., Sakam S., Chilimuri S. Cytomegalovirus related fatal duodenal diverticular bleeding: case report and literature review. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016;22(31):7166–7174. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i31.7166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keates J., Lagahee S., Crilley P., Haber M., Kowalski T. CMV enteritis causing segmental ischemia and massive intestinal hemorrhage. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2001;53(3):355–359. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(01)70417-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hagiya H., Iwamuro M., Tanaka T., Hanayama Y., Otsuka F. Cytomegalovirus as an insidious pathogen causing duodenitis. Acta Med. Okayama. 2015;69(5):319–323. doi: 10.18926/AMO/53679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ko J., Peck K.R., Lee W.J., Lee J.Y., Cho S.Y., Ha Y.E. Clinical presentation and risk factors for cytomegalovirus colitis in immunocompetent adult patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2015;60(6):e20–6. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Siciliano R.F., Castelli J.B., Randi B.A., Vieira R.D., Strabelli T.M. Cytomegalovirus colitis in immunocompetent critically ill patients. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2014;20:71–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2013.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Humar A., Gregson D., Caliendo A.M., McGeer A., Malkan G., Krajden M. Clinical utility of quantitative cytomegalovirus viral load determination for predicting cytomegalovirus disease in liver transplant recipients. Transplantation. 1999;68(9):1305–1311. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199911150-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blanshard C., Benhamou Y., Dohin E., Lernestedt J.O., Gazzard B.G., Katlama C. Treatment of AIDS-associated gastrointestinal cytomegalovirus infection with foscarnet and ganciclovir: a randomized comparison. J. Infect. Dis. 1995;172(3):622–628. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.3.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilcox C.M., Straub R.F., Schwartz D.A. Cytomegalovirus esophagitis in AIDS: a prospective evaluation of clinical response to ganciclovir therapy, relapse rate, and long-term outcome. Am. J. Med. 1995;98(2):169–176. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)80400-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim Y.S., Kim Y.H., Kim J.S., Cheon J.H., Ye B.D., Jung S.A. The prevalence and efficacy of ganciclovir on steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis with cytomegalovirus infection: a prospective multicenter study. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2012;46(1):51–56. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3182160c9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Further reading

[17] R.A. Agha, A.J. Fowler, A. Saetta, I. Barai, S. Rajmohan, D.P. Orgill, The SCARE Group, The SCARE statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines, Int. J. Surg., 34 (2016) 180–186.