Highlights

-

•

Although rare, celiac artery aneurysm may carry a definite risk for rupture and other complications.

-

•

Because of its rarity, no strong consensus concerning indications for intervention of asymptomatic celiac artery aneurysm exists in the literature.

-

•

Clinicians awareness regarding this rare entity and efforts to discover before rupturing are imperative.

Keywords: Celiac aneurysm, Splanchnic aneurysm, Surgical repair

Abstract

Background

Celiac artery aneurysm is a rare vascular lesion. It is frequently discovered after rupture, which leads to death in most cases. We present a case of an asymptomatic celiac artery aneurysm discovered in a 72-year-old female during an evaluation for high grade fever and general fatigue.

Case presentation

The patient visited our department with complaints of fever and general fatigue. The patient’s medical history included type 2 diabetes mellitus with poor control and hypertension. Blood culture and urine culture that were submitted at arrival presented E. Coli. Then, she was diagnosed with bacteremia by urinary tract infection. Transesophageal echocardiography revealed no vegetation at her valves. Computed tomography was performed for investigating her urological abnormalities, revealing a 28 × 30 mm aneurysm at the trunk of the celiac artery. Blood and urine cultures submitted at arrival were positive for E. coli. Surgical repair performed after the improvement of her urinary tract infection revealed a non-infective aneurysm; thus, aneurysm closure and prosthetic grafting were conducted.

Conclusion

Clinician awareness regarding this rare entity and discovery efforts to discover the splanchnic aneurysm before rupturing are imperative.

1. Introduction

Celiac artery aneurysm is a quite uncommon vascular lesion, accounting for 5.1% of all splanchnic artery aneurysms [1]. Although rare, celiac artery aneurysm carries a definite risk for rupture and other complications [2]. However, because of its rarity, no strong consensus concerning indications for intervention of asymptomatic celiac artery aneurysm exists in the literature. Due to more frequent use of cross-sectional imaging, the dilemma of choosing the appropriate therapeutic option has become increasingly more important. Herein, we present a case of an un-ruptured celiac artery aneurysm that was treated by surgical repair and also discuss the appropriate therapeutic strategy based on a literature review.

2. Case presentation

A 72-year-old female visited our department with complaints of fever and general fatigue. The patient’s medical history included type 2 diabetes mellitus with poor control and hypertension. She has no history of infectious disease or trauma. She denied any tobacco and alcohol use. Physical examination upon arrival revealed that her blood pressure was 147/62 mmHg, heart rate was 104 beats/min with regular rhythm, blood oxygen saturation was 95% under atmospheric conditions, and body temperature was 38.7 °C. Blood analyses revealed 11,260 white blood cells/μl with 80.6% neutrophils and 0.69 mg/dl C-reactive protein); mild hypoalbuminemia (3.3 g/dl); coagulant dysfunction (fibrin/fibrinogen degradation products; 7 μg/dl fibrinogen; and 2.1 μg/ml D-dimer), and severely impaired glucose tolerance (157 mg/dl and 11.2% hemoglobin A1c). Further, mildly increased gamma-glutamyltransferase (215 IU/l) and alkaline phosphatase (671 IU/l) were also revealed. At her initial clinical examination, she weighed 52.4 kg, was 150 cm tall, and had a body mass index was 23.3 kg/m2. Inspection of the palpebral conjunctiva revealed no evidence of anemia. Chest auscultation revealed no signs of abnormal heart murmurs and no rales or other abnormal respiratory sounds. The abdomen was slightly distended and her peristalsis was normal; no tenderness was observed in the upper abdomen. No mass was palpable, and there were no signs of peritoneal irritation. Physical examination showed no edema or cyanosis.

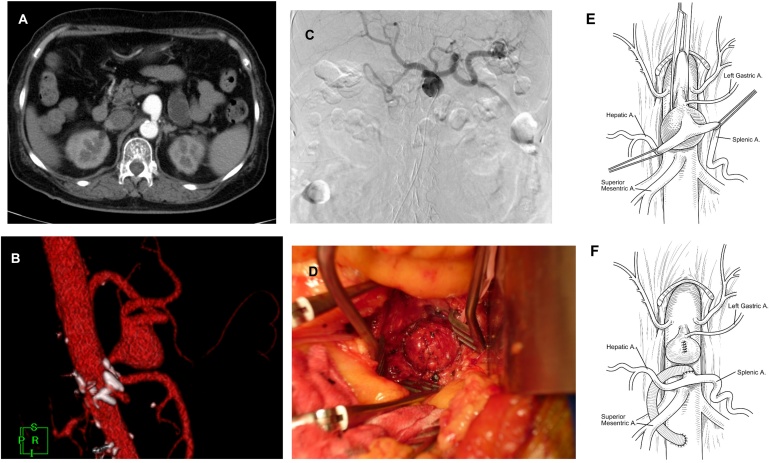

Electrocardiography revealed a normal, regular heart rhythm without ischemic changes. Chest radiography revealed nothing that suggested infected lesions. Blood culture and urine culture that were submitted at arrival revealed E. coli. She was then diagnosed with bacteremia by urinary tract infection and antibacterial medicine (cefmetazole 2 g per day) was initiated. Transesophageal echocardiography was performed to investigate infective endocarditis, revealing no vegetation at her valves. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) was performed for investigating her urological abnormalities, revealing no urological deformities but a 28 × 30 mm sized aneurysm at the trunk of the celiac artery (Fig. 1A, B). Based on the angiography finding, the proper hepatic artery was dominantly supplied from the celiac artery, the left gastric artery being bifurcated from the celiac trunk, and the celiac artery and the splenic and common hepatic artery had a common trunk (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

A) Contrast-enhanced computed tomography revealed a 28 × 30 mm size celiac artery aneurysm 10 mm distal to the outlet of the artery. B) Volume rendering of computed tomography revealed an aneurysm that had a common trunk of the hepatic and splenic artery. C) Angiography revealed that blood flow of proper hepatic artery was dominantly supplied from the celiac artery. D) Surgical findings revealed an exposed celiac artery aneurysm. E, F) Schema shows pre- and post-operative findings.

Surgical repair of the aneurysm was performed after confirmation of negative blood culture for bacteria on day 32.

Upper abdominal midline was performed under general anesthesia. Firstly, lesser omentum and crus of diaphragm were incised to expose abdomen aorta at the level of the trunk of the celiac artery. The proper hepatic artery was taped at the hepatic hilus. After that, the superior mesenteric artery was taped at the trunk of the small bowel mesentery. The celiac artery aneurysm was exposed. The left gastric artery was bifurcated from the common hepatic artery. The common hepatic and splenic artery were taped. Then, abdominal aorta was exposed at the level of the renal artery. Abdominal aorta was clamped both at the head of celiac artery and at the level of renal artery to prevent blood flow. The aneurysm was incised to ligate it from the inside. Then, abdominal aorta was declamed after 12 min of clamping time. The distal celiac artery of the aneurysm was cut and 8 mm size prosthetic graft was anamotosed. Another end of the prosthetic graft was anamostosed through the dorsum of duodenum to abdominal aorta below the level of renal artery (Fig.1D, E, F). The greater omemtum was intervened to prevent infections.

Postoperative course was uneventful and she was discharged on day 47.

3. Discussion

Celiac artery aneurysm is an uncommon type of splanchnic artery aneurysm that carries a high risk for mortality if it ruptures. A total of 9.1% of celiac artery aneurysms are accompanied by abdominal aortic aneurysms [1]; solitary celiac artery aneurysms not accompanied by other aneurysms are extremely rare. Etiology of celiac artery aneurysm includes infectious diseases, atherosclerosis, trauma, or congenital conditions [2]. Atherosclerotic degeneration is the most common cause. Other causes of celiac artery aneurysm include medial necrosis, inflammation, trauma, and median arcuate ligament syndrome. In our patient, the cause of the aneurysm was presumably derived from atherosclerosis due to the poor-controlled diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and aging.

Since most patients are asymptomatic, celiac artery aneurysm is frequently incidentally discovered by imaging modalities for the investigation of other conditions or diseases [3]. The major presentation of celiac artery aneurysm is gastrointestinal symptoms, including abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, appetite loss, or symptoms of mesenteric ischemia.

Rupture is a devastating presentation, with reported mortality rates ranging from 25 to 70% [4]. The aneurysm may rupture into the peritoneal cavity, retroperitoneum, or thorax.

The ideal approach to management of asymptomatic patients remains elusive. Treatment depends on the aneurysm’s size, presentation, and location. The risk of rupture of 15–22 mm diameter celiac artery aneurysms is 5%; in contrast, the risk of rupture in >30 mm diameter aneurysms is 50–70% [5]. In general, treatment is considered for asymptomatic patients when the aneurysm is larger than 20 mm in diameter [2], [4].

The rudiment of operative treatment is the resection or closure of the aneurysm along with revascularization of peripheral branches that bifurcate from the celiac artery aneurysm. Surgical repair of the aneurysm with prosthetic grafts demonstrated more preferable long-term results than by using saphenous veins; thereby, prosthetic grafts might become the mainstay of surgical aneurysm repair [4]. Surgical treatment of a celiac artery aneurysm that involves the confluence of trifurcation is challenging, with a mortality risk of 5% [6], [7].

When the aneurysm is removed without the vascular reconstruction, the blood flow from the super mesenteric artery to the hepatic artery should be carefully examined before surgery [8]. In recent years, with advances in interventional radiology, catheter embolization is also attempted. When catheter embolization is adopted, the blood flow from the super mesenteric artery to the hepatic artery should be confirmed. Clearly, if gross liver ischemia is found after aneurysm resection, revascularization of the hepatic artery is necessary, either by antegrade supraceliac aortohepatic bypass or retrograde inflow from the infrarenal segment of the aorta or the common iliac arteries. In our case, angiography confirmed that the blood flow of the proper hepatic artery was dominantly supplied by the celiac artery and the gastroduodenal artery was patent and large.

Endovascular techniques, including stent implantation and embolization of aneurysms are feasible in the setting of advanced age and underlying diseases; while surgical intervention is a safe and effective method in selected cases [9], [10]. In our patient, endovascular treatment was considered unsuitable because the patient just recovered from bacteremia and the possibility of an infective aneurysm could not be excluded. In addition, surgical intervention was not likely to be challenging considering the anatomical location of the aneurysm and the patient’s favorable general condition.

Clearly, the celiac artery aneurysm in our patient was concluded not derived from infections based on the clinical course and operative findings. A question may be raised about why this patient should have undergone CT although she did not present any abdominal complaints. Patients with urosepsis should be scrutinized with imaging modalities in search of urological abnormalities or malformations irrespective of their symptoms [11].

4. Conclusion

Although rare, clinicians should be aware of celiac artery aneurysms and make efforts to discover them at an early stage, even during the investigation of other diseases or symptoms. Furthermore, early treatment of unruptured celiac artery aneurysm may sometimes be required to protect rupture or mesenteric ischemia from distal embolization.

Conflicts of interest

All authors of this manuscript declare no conflicts of interests.

Funding

No funding support was given for this study.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by Okayama University Hospital Ethical Committee.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request”.

Author contributions

Nobuhiro Takeuchi and Junichi Soneda performed surgery. Hiromichi Naito, Atsuyoshi Iida, Tetsuya Yumoto and Kohei Tsukahara contributed to the study design, data collections, data analysis, writing and review. Atsunori Nakao contributed to the data collections and review.

Registration of research studies

Not applicable.

Guarantor

Corresponding author.

Declaration

We declare that our case is compliant with the SCARE criteria [12].

Informed consent

Consents, permissions, and releases were obtained where authors wished to include case details or images of patients and any other individuals in an Elsevier publication.

Acknowledgement

No funding supported this study.

Contributor Information

Nobuhiro Takeuchi, Email: takeuchi1207@yahoo.ne.jp.

Junichi Soneda, Email: soneda@kobetokusyukai.jp.

Hiromichi Naito, Email: naito05084@gmail.com.

Atsuyoshi Iida, Email: atsuyoshiiida1656@gmail.com.

Tetsuya Yumoto, Email: tetsujaam@yahoo.co.jp.

Kohei Tsukahara, Email: hei.trp@gmail.com.

Atsunori Nakao, Email: qq-nakao@okayama-u.ac.jp.

References

- 1.Pulli R., Dorigo W., Troisi N., Pratesi G., Innocenti A.A., Pratesi C. Surgical treatment of visceral artery aneurysms: a 25-year experience. J. Vasc. Surg. 2008;48(2):334–342. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stone W.M., Abbas M.A., Gloviczki P., Fowl R.J., Cherry K.J. Celiac arterial aneurysms: a critical reappraisal of a rare entity. Arch. Surg. 2002;137(6):670–674. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.137.6.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McMullan D.M., McBride M., Livesay J.J., Dougherty K.G., Krajcer Z. Celiac artery aneurysm: a case report. Tex. Heart Inst. J. 2006;33(2):235–240. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pasha S.F., Gloviczki P., Stanson A.W., Kamath P.S. Splanchnic artery aneurysms. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2007;82(4):472–479. doi: 10.4065/82.4.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rokke O., Sondenaa K., Amundsen S., Bjerke-Larssen T., Jensen D. The diagnosis and management of splanchnic artery aneurysms. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 1996;31(8):737–743. doi: 10.3109/00365529609010344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.D'Ayala M., Deitch J.S., deGraft-Johnson J. Giant celiac artery aneurysm with associated visceral occlusive disease. Vascular. 2004;12(6):390–393. doi: 10.1258/rsmvasc.12.6.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Connell J.M., Han D.C. Celiac artery aneurysms: a case report and review of the literature. Am. Surg. 2006;72(8):746–749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kadoya M., Kondo S., Hirano S., Ambo Y., Tanaka E., Takemoto N. Surgical treatment of celiac-splenic aneurysms without arterial reconstruction. Hepatogastroenterology. 2007;54(76):1259–1261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang W., Fu Y.F., Wei P.L., E B, Li D.C., Xu J. Endovascular repair of celiac artery aneurysm with the use of stent grafts. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2016;27(4):514–518. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2015.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carrafiello G., Rivolta N., Annoni M., Fontana F., Piffaretti G. Endovascular repair of a celiac trunk aneurysm with a new multilayer stent. J. Vasc. Surg. 2011;54(4):1148–1150. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.03.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sørensen S.M., Schønheyder H.C., Nielsen H. The role of imaging of the urinary tract in patients with urosepsis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2013;17(5):e299–303. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2012.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Saeta A., Barai I., Rajmohan S., Orgill D.P., SCARE Group The SCARE statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016;34:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]