Highlights

-

•

Secondary perineal hernia can develop after abdominoperineal resection of the rectum.

-

•

An incarcerated secondary perineal hernia caused strangulated bowel obstruction.

-

•

Wound-healing-delaying factors are the risk factors for perineal hernia development.

-

•

The pelvic floor and peritoneum should be repaired via laparoscopic rectum surgery.

Keywords: Strangulated bowel obstruction, Perineal hernia, Laparoscopic surgery, Abdominoperineal resection, Alcoholic cirrhosis, Rectal cancer, Internal fixation

Abstract

Introduciton

We report a recent case of strangulated bowel obstruction due to an incarcerated secondary perineal hernia that developed after laparoscopic rectal resection.

Presentation of case

A 75-year-old man undergoing treatment for alcoholic cirrhosis underwent laparoscopic abdominoperineal resection of the rectum (APR) for lower rectal cancer after preoperative chemoradiotherapy. Lung metastases were diagnosed 2 months postoperatively. Ten days after chemotherapy initiation, the patient was hospitalized on an emergency basis due to hepatic encephalopathy. Ten days thereafter, we observed perineal skin protrusion. Moreover, the skin disintegrated spontaneously, resulting in ascetic fluid outflow. Pain and fever developed, with inflammatory reactions. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography showed strangulated small bowel obstruction due to perineal hernia. We performed an emergency surgery, during which we found small intestine wall incarcerated in the pelvic dead space, with thickening and edema; no necrosis or perforation was observed. We performed internal fixation by introducing an ileus tube into the ileocecum and fixing its balloon at the cecal terminus.

Discussion

Secondary perineal hernia is rare and can develop after APR. Its prevalence is likely to increase in future because of the increasing ubiquity of laparoscopic APR, in which no repair of peritoneal stretching to the pelvic floor is performed. However, only two case of secondary perineal hernia causing strangulated bowel obstruction has been reported in the literature. The follow-up evaluation of our procedures and future accumulation of cases will be important in raising awareness of this clinical entity.

Conclusion

We suggest that the pelvic floor and the peritoneum should be repaired.

1. Introduction

Secondary perineal hernia is thought to develop after approximately 1% of abdominoperineal resections of the rectum (APRs) and 3–10% of pelvic malignant tumor resections, indicating that it is a rare condition [1]. Herein, we report a recent case of strangulated bowel obstruction due to an incarcerated secondary perineal hernia that developed after laparoscopic rectal resection. We accompany our observations with a brief review of the current literature.

2. Presentation of case

A 75-year-old man presented to our institution with perineal bulging, spontaneous perineal skin disintegration and fluid leakage, and fever. His medical history included alcoholic cirrhosis (Child-Pugh score = B) at 61 years of age and a left inguinal hernia at 67 years of age, for which he underwent surgery.

History of the reported illness was as follows: 14 months prior to the development of strangulated bowel obstruction, the patient had undergone laparoscopic APR after preoperative chemoradiotherapy (1.8 Gy for 28 sessions, S-1(Tegafur/Gimeracil/Oteracil) 100 mg/day) for progressive lower rectal cancer. The final disease stage was RbP, pT3, N1, cH0, cM0, stage IIIa. Multiple lung metastases were diagnosed on contrast-enhanced computed tomography 2 months postoperatively. Ascites due to cirrhosis were seen below the skin of the perineal wound. After preventive endoscopic ligation of the esophageal varices caused by alcoholic cirrhosis, modified FOLFOX-6 was started to treat the lung metastases approximately 5 months after APR. Because the patient developed hepatic encephalopathy due to alcohol intake 10 days after treatment, he was hospitalized on an emergency basis. He was then treated with bed rest, the administration of a branched-chain amino acid preparation. However, 10 days after admission, protrusion of the peritoneal skin was observed with spontaneous disintegration, resulting in the outflow of ascetic fluid the next day and pain and fever the following day. Blood examination revealed an increase of inflammatory reactions, and contrast-enhanced computed tomography revealed invagination of the small intestine in the pelvic cavity, intestinal edema, and attenuation of the contrast effect. Therefore, we diagnosed him with strangulated small bowel obstruction due to perineal hernia.

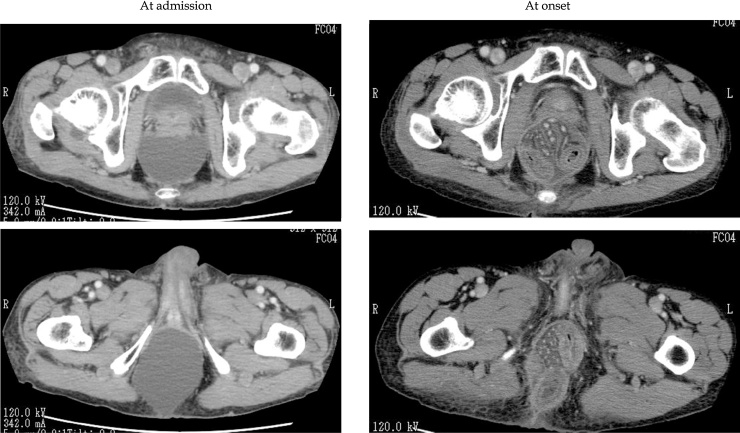

A fist-sized mass was detected in the perineum. The mass was soft, and could be easily repositioned (Fig. 1). Abdominal contrast-enhanced computed tomography revealed a hernia in the perineum after APR, and prolapse of the small intestine from the level of the pelvic floor muscle was also observed (Fig. 2). We diagnosed the patient with a secondary perineal hernia, and he underwent surgery under general anesthesia.

Fig. 1.

Preoperative photo showing large perineal swelling (arrows) in the lithotomy position.

Fig. 2.

Computed temography image of the pelvis demonstrating a strang ulated perineal hernia.

Surgical findings included the following: the small intestine was pulled back from the incarceration in the pelvic cavity, revealing thickening of and edema on the wall but no necrosis or perforation. For this reason, no intestinal resection was performed (Fig. 3). To prevent recurrence, we chose internal fixation. We introduced an ileus tube into the cecum and inflated its balloon at the cecal terminus to keep the position (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

The small intestine on the verge of necrosis in the pelvic floor.

Fig. 4.

Plain abdominal radiograph: An ileus tube was pushed into the ileocecum and its balloon was fixed at the cecal terminus.

After surgery, the pelvic dead space was infected, which was managed with drainage. He experienced no recurrence of hernia to date (six months postoperatively).

This case report was written in accordance with the SCARE Guidelines [2].

3. Discussion

Perineal hernias are classified as either primary [1], which occur due to vulnerability of the pelvic floor muscles, or secondary, which occur due to surgery in the peritoneal cavity, including that performed for rectal cancer. Secondary perineal hernias after rectal resection for rectal cancer were reported for the first time in 1939 by Yeomans [3]. In addition, perineal hernia due to laparoscopic APR was reported for the first time in 2007 by Veenhof [4]. Our recent search of the PubMed database with the keywords “perineal hernia” from January 1989–May 2016 yielded only two previous case reports of perineal hernia that led to a strangulated bowel obstruction; though reports of secondary perineal hernia after laparoscopic APR are increasing. Our report therefore is the third of its kind in the literature. Table 1 summarizes the two reported cases; including the details of the present case [5], [6]. It is thought that the development of secondary perineal hernia within 1 year postoperatively is common [1]. In three cases; the hernia developed after an average of 10 months postoperatively. Factors associated with the development of secondary perineal hernia that have been discussed include the presence of large mesentery allowing invagination [7]; the presence or absence of coccygectomy [8]; the presence or absence of peritoneal repair during surgery [9]; and intraoperative injury of the levator ani muscle [9]. The low incidence of adhesion is likely to be involved in the development of perineal hernia after laparoscopic surgery [10]. Indeed; this could be possible; as very little evidence of adhesion was found when we performed re-incision of the abdomen during surgery. In addition; the omission of repair of the peritoneum due to the complicated nature of this procedure during laparoscopic rectal resection is also likely to have influenced the development of the hernia.

Table 1.

Strangulation of the ileus by perineal hernia after laparoscopic abdominoperineal resection (APR) of the rectum.

| Case | First author Ref. | Year | Age (years), sex | Condition | Comorbidities | Pre-treatment | Interval from APR (months) | Symptom | Approach | Intra-abdominal adhesion | Repair |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Simon [4] | 2013 | 81, F | Rectal cancer | None | None | 24 | Abdominal pain, vomiting | Abdominal | Yes | Strattice™ Tissue Matrix |

| 2 | Harris [5] | 2015 | 60, M | GIST | None | Imatinib | 1 | Vomiting, abdominal pain, distension, cessation of stoma | Abdominal | Yes | Mesh |

| 3 | Current case | 2016 | 75, M | Rectal cancer | Alcoholic liver cirrhosis | S-1, Radiation | 6 | Perineal pain, fever | Abdominal | No | Internal fixation with an ileus tube |

GIST = Gastrointestinal stromal tumor; F = Female; M = male.

Wound-healing-delaying factors such as postoperative wound infections and diabetes mellitus are considered to be risk factors for the development of perineal hernia [11]. Indeed, our case involved alcoholic cirrhosis. Generally, chemotherapy induces malnutrition due to its adverse effects on the digestive system, among other effects, that lead to delayed wound healing in some cases. Hence, the preoperative chemoradiotherapy administered to our patient was likely involved in the development of the secondary perineal hernia.

Currently, surgery is considered the only option for the treatment of secondary perineal hernia [1]. A transabdominal or transperineal approach, or laparoscopic surgery, is used to treat hernia. In the present case, we chose laparotomy because it was suspected before surgery that the small intestine and hernial contents might be necrotic, though we performed laparoscopic surgery prior to this. Repair of the hernial orifice includes closure by simple suturing and repair using a mesh. In the present case, we felt that there was no choice but to perform internal fixation using an ileus tube because of the infection risk. In recent years, the increased use of laparoscopic surgery and the advancement of postoperative chemotherapy for large bowel cancer, including rectal cancer, are remarkable [12], [13], [14]. The incidence of strangulated bowel obstruction due to secondary perineal hernia may increase in the future. Therefore, we believe that the pelvic floor and the peritoneum should be repaired whenever possible using laparoscopic surgery of the rectum in the presence of a wound-healing-delaying factor(s) such as cirrhosis. Additionally, due to the existence of only three reports of strangulated bowel obstruction caused by secondary perineal hernia, the mechanism of development, the method of prevention, and the operative method all remain unknown. As it appears necessary to choose a therapeutic approach tailored to each individual patient’s characteristics and clinical findings, case reports should be further accumulated and examined in the future.

4. Conclusion

We reported the case of a patient with strangulated bowel obstruction due to an incarcerated secondary perineal hernia after laparoscopic APR. We suggest that the pelvic floor and the peritoneum should be repaired, whenever possible, via laparoscopic surgery of the rectum in the presence of a wound-healing-delaying factor and that internal fixation is also effective, not mesh, as an option to prevent recurrence if there is a risk of infection.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest associated with this manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Consent

Informed consent was obtained from the patient before using his data.

Author contribution

Giichiro Tsurita designed the study. Tomohiro Kurokawa wrote the initial draft of the manuscript. Masaru Shinozaki contributed to analysis and interpretation of data, and assisted in the preparation of the manuscript. All other authors have contributed to data collection.

Guarantor

Tomohiro Kurokawa, Giichiro Tsurita.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cali R.L., Pitsch R.M., Blatchford G.J., Thorson A., Christensen M.A. Rare pelvic floor hernias: report of a case and review of the literature. Dis. Colon Rectum. 1992;35:04–12. doi: 10.1007/BF02050544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Saetta A., Barai I., Rajmohan S., Orgill D.P. and the SCARE group. The SCARE statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016;34:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yeomans F.C. Levator hernia, perineal and pudendal. Am. J. Surg. 1939;43:695–697. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Veenhof A.A., van der Peet D.L., Cuesta M.A. Perineal hernia after laparoscopic abdominoperineal resection for rectal cancer: report of two cases. Dis. Colon Rectum. 2007;50:1271–1274. doi: 10.1007/10350-007-0214-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fallis Simon A., Taylor Lewis H., Tiramularaju R.M.R. Biological mesh repair of a strangulated perineal hernia following abdominoperineal resection. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2013;4:rjt023. doi: 10.1093/jscr/rjt023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harris C.A., Keshava A. Education and Imaging: gastrointestinal: laparoscopic repair of acute perineal hernia causing complete small bowel obstruction. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015;30:1692. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kelly A.R. Surgical repair of postoperative hernia. Aust. N. Z. J. Surg. 1960;29:243–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1960.tb03845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cattel R.B., Cunningham R.M. Post- operative perineal hernia following resection of the rectum. Surg. Clin. Notth Am. 1944;24:679–683. [Google Scholar]

- 9.McMullin N.D., Johnson W.R., Polglase A.L., Hughes E.S. Post-proctectomy perineal hernia. Case report and discussion. Aust. N.Z. J. Surg. 1985;55:69–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1985.tb00858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miyashita T., Harigai M., Goto T. A case of laparoscopic pelvic floor plasty for perineal hernia that developed after laparoscopic rectal resection for anal canal cancer. Nihon Rinsho Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 2007;68:2145. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakajima S., Suwa K., Kitagawa K., Yanaga K. Perineal hernia after abdominoperineal proctectomy: report of two cases. Nippon Daicho Komonbyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2010;(B):75–81. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jayne D.G., Guillou P.J., Thorpe H., Quirke P., Copeland J., Smith A.M., Heath R.M., Brown J.M. UK MRC CLASICC trial group. Randomized trial of laparoscopic-assisted resection of colorectal carcinoma: 3-year results of the UK MRC CLASICC trial group. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007;25:3061–3068. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.7758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schoetz D.J., Jr. Evolving practice patterns in colon and rectal surgery. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2006;203:322–327. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2006.05.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aziz O., Constantinides V., Tekkis P.P., Athanasiou T., Purkayastha S., Paraskeva P., Darzi A.W., Heriot A.G. Laparoscopic versus open surgery for rectal cancer: a meta-analysis. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2006;13:413–424. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2006.05.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]