Abstract

Hepatitis C virus infection is a major cause of hepatocellular carcinoma worldwide. Interferon has been the major antiviral treatment, yielding viral clearance in approximately half of patients. New direct-acting antivirals substantially improved the cure rate to above 90%. However, access to therapies remains limited due to the high costs and under-diagnosis of infection in specific subpopulations, e.g., baby boomers, inmates, and injection drug users, and therefore, hepatocellular carcinoma incidence is predicted to increase in the next decades even in high-resource countries. Moreover, cancer risk persists even after 10 years of viral cure, and thus a clinical strategy for its monitoring is urgently needed. Several risk-predictive host factors, e.g., advanced liver fibrosis, older age, accompanying metabolic diseases such as diabetes, persisting hepatic inflammation, and elevated alpha-fetoprotein, as well as viral factors, e.g., core protein variants and genotype 3, have been reported. Indeed, a molecular signature in the liver has been associated with cancer risk even after viral cure. Direct-acting antivirals may affect cancer development and recurrence, which needs to be determined in further investigation.

Keywords: Hepatitis C virus, Hepatocellular carcinoma, Interferon, Direct-acting antivirals, Sustained virologic response

Background

Chronic infection of hepatitis C virus (HCV), estimated to affect more than 150 million individuals globally, has proven a major health problem by causing liver cirrhosis and cancer. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the major liver cancer histological type, is the second leading cause of cancer mortality worldwide [1]. Interferon-based regimens have been the mainstay of anti-HCV therapy, yielding HCV cure, or sustained virologic response (SVR), in approximately 50% of patients [2]. Recently developed direct-acting antivirals (DAAs), which directly target the viral protease, polymerase, or non-structural proteins, have enabled interferon-free anti-HCV therapies with a revolutionary improvement of SVR rate, approaching or surpassing 90% [3]. Despite the unprecedentedly high antiviral efficacy, access to therapy remains limited, at less than 10% of the total number of HCV-infected individuals, especially in developing countries, due to the high drug costs [4, 5]. In addition, the high frequency of unrecognized HCV infection in the general and specific (e.g., inmates and homeless) populations, estimated at 50% or above of infected individuals, hampers control of the virus even with the commercialization of DAAs [5, 6]. With the 3–4 million newly infected cases each year, it is estimated that the HCV-associated disease burden will remain high in the next decade, even in developed countries [7–9].

Wider use of DAAs has revealed several limitations, including more refractory genotype 1a or 3 virus, emergence of resistant HCV stains with characteristic resistance-associated substitutions, and poorer response in prior non-responders to interferon-based therapies [10]. These findings warrant further development of alternative strategies such as the application of specific DAA combination therapies to target resistant HCV strains, host targeting agents/viral entry inhibition, and the development of diagnostic tools to monitor therapeutic progress and success [11–14]. Even after SVR, re-infection can occur in up to 10–15% of patients, especially in high-risk populations such as injection drug users [15–17]. Post-transplantation graft re-infection is also a critical issue given that most liver explants (67%) remain HCV RNA positive in the liver despite undetectable blood HCV RNA [18]. In these clinical scenarios, a prophylactic vaccine is likely to be an effective option. Although HCV vaccine development is challenging due to the high viral genetic variability, promising progress has been made to date [16]. Thus, complementary antiviral approaches including improved and more accessible therapies as well as the development of a prophylactic vaccine will be necessary to achieve impactful global control of infection that leads to HCV eradication, namely a reduction of regional incidence close to zero.

Effect of HCV cure on HCC development

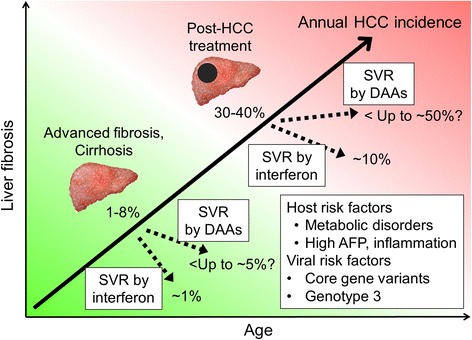

HCV-induced progressive liver fibrosis and aging are well-established high-risk conditions for HCC development (Fig. 1) [1]. Of note, the highly carcinogenic “field effect” in fibrotic/cirrhotic livers leads to repeated recurrence of de novo HCC tumors even after curative treatment of the initial primary tumors. The effect of achieving an SVR on HCC risk has been reported in multiple retrospective cohorts of patients who were mostly treated with interferon-based therapies (Table 1); these studies consistently showed significant reduction of HCC incidence in SVR patients. A pooled analysis of 12 observational studies with a total of 25,497 patients showed that interferon-induced SVR resulted in an approximately four-fold reduction of HCC risk irrespective of liver disease stage (hazard ratio, 0.24; P < 0.001) [19]. Annual HCC incidence in patients with advanced liver fibrosis or cirrhosis and active HCV infection is reported to range from 1% to 8% [1], reducing to 0.07% to 1.2% after achieving an SVR by interferon-based therapies (Table 1). SVR is also implicated in reduction of all-cause mortality, which may alter patient prognosis to the level of the general population, although this is yet to be established [20, 21]. In cirrhotic patients who failed to achieve SVR, subsequent maintenance low-dose interferon treatment reduced annual HCC incidence to 1.2% when compared to 4.0% in untreated patients (hazard ratio, 0.45; P = 0.01) [22]. This result suggests that the anti-inflammatory and/or immunomodulatory effects of interferon may have HCC-preventive effects irrespective of HCV presence, although the adverse effects (flu-like symptoms, neuropsychiatric and myelosuppressive effects) hamper its wider use [1]. DAAs are shown to be less toxic, and are expected to overcome the limitations of interferon-based therapies. DAAs were indeed well-tolerated even in compensated and decompensated cirrhosis patients in recent clinical trials [23, 24]. However, their HCC preventive effect is still only partially understood.

Fig. 1.

Natural history of HCV-related HCC development and modulation by anti-HCV therapies. Progressive liver fibrosis along with aging gradually increases the risk of hepatocarcinogenesis, which could be further accelerated by several host and viral risk factors. Annual incidences of HCC development and recurrence after DAA-based SVR were estimated from retrospective and prospective studies summarized in Table 1. SVR induced by interferon- or DAA-based anti-HCV therapies may result in distinct post-SVR HCC risk. AFP alpha-fetoprotein, DAA direct-acting antiviral, HCV hepatitis C virus, HCC hepatocellular carcinoma, SVR sustained virologic response

Table 1.

Incidence of post-sustained virologic response (SVR) hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) development and recurrence

| Author (year), Reference | Major race | Country | Type of anti-HCV therapy | n | Follow-up, median, years | Male sex, n (%) | Age, median, years | Advanced fibrosis/cirrhosis, n (%) | Treatment for previous HCC | Reported HCC incidence in SVR, % (interval in years) | Annual HCC incidence in SVR, % | Reported HCC incidence in non-SVR, % (interval in years) | Annual HCC incidence in non-SVR, % | Study design |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCC development | ||||||||||||||

| Akuta (2011) [34] | Asian | Japan | IFN-based | 1273 | 1.1 | 783 (61.5) | 53 | 109 (8.6) | – | 3.2 (5) | 0.65 | – | – | Retrospective |

| Chang (2012) [51] | Asian | Taiwan | IFN-based | 1271 (including 400 non-SVR) | 3.4 | 661 (75.9) | 55.4a | 355 (27.9) | – | 1.2 (3) | 0.4 | – | – | Retrospective |

| Huang (2014) [52] | Asian | Taiwan | IFN-based | 642 | 4.4 | 302 (54.3) | 51.4a | 86 (13.4) | – | 5.8 (5) | 1.2 | – | – | Retrospective |

| Yamashita (2014) [53] | Asian | Japan | IFN-based | 562 | 4.8 | 311 (55.3) | 57 | 129 (23.0) | – | 3.1 (5) | 0.63 | – | – | Retrospective |

| Oze (2014) [54] | Asian | Japan | IFN-based | 1425 | 3.3 | 727 (51.0) | 54.5 | 118 (11.6) | – | 2.6 (5) | 0.53 | 11.7 (5) | 2.49 | Prospective |

| Toyoda (2015) [55] | Asian | Japan | IFN-based | 522 | 7.2 | 292 (55.9) | 50.6 | 27 (5.5) | – | 1.2 (5) | 0.24 | – | – | Retrospective |

| Wang (2016) [56] | Asian | Taiwan | IFN-based | 376 | 7.6 | 185 (49.2) | 54.1 | 127 (33.8) | – | 1.4 (5) | 0.28 | – | – | Retrospective |

| Kobayashi (2016) [57] | Asian | Japan | IFN-based | 528 | 7.3 | 308 (58.4) | 54 | 78 (14.8) | – | 2.2 (5) | 0.44 | – | – | Retrospective |

| El-Serag (2016) [36] | Caucasian | USA | IFN-based | 10,738 | 2.8 | 10,232 (95.3) | 53.1a | 1548 (14.4) | – | 0.33 (5) | 0.07 | – | – | Retrospective |

| Nagaoki (2016) [58] | Asian | Japan | IFN-based | 1094 | 4.2 | 585 (53.5) | 60 | 208 (1.9) | – | 4.0 (5) | 0.82 | – | – | Retrospective |

| Tada (2016) [59] | Asian | Japan | IFN-based | 587 | 14.0 | 324 (55.2) | 50 | – | – | 4.4 (10) | 0.45 | 14.7 (10) | 1.59 | Retrospective |

| Tada (2016) [60] | Asian | Japan | IFN-based | 170 | 14.2 | 106 (62.4) | 52.5 | – | – | 7.1 (10) | 0.74 | – | – | Retrospective |

| van der Meer (2016) [61] | Caucasian | Europe and Canada | IFN-based | 1000 | 5.7 | 676 (68.0) | 52.7 | 842 (85.0) | – | 7.6 (8) | 0.99 | – | – | Retrospective |

| Kobayashi (2016) [57] | Asian | Japan | DAAs | 77 | 4.0 | 34 (44.2) | 63 | 23 (29.9) | – | 3.0 (5) | 0.62 | – | – | Retrospective |

| HCC development or recurrence | ||||||||||||||

| Conti (2016) [39] | Caucasian | Italy | DAAs | 344 (59 had previous HCC, including 30 non-SVR) | 0.5 | 207 (60.1) | 63 | 39 (11.3) | Resection, ablation, TACE | 3.2 (0.5)d | 6.3d | – | – | Retrospective |

| Cheung (2016) [24] | Caucasian | UK | DAAs | 317 (18 had previous HCC) | 1.3 | NA | 54 | 254 (80.1) | Resection, ablation, TACE | 5.4 (1.3) | 4.27 | 11.2 (1.3) | 9.14 | Prospective |

| HCC recurrence | ||||||||||||||

| Saito (2014) [62] | Asian | Japan | IFN-based | 14 | 3.9 | 13 (92.9%) | 72 | 12 (85.7) | Resection, ablation | 18.0 (3) | 6.62 | 75.3 (3) | 46.61 | Retrospective |

| Huang (2015) [63] | Asian | Taiwan | IFN-based | 56 | 4.4 | 36 (64.3) | 61.6 | 21 (37.5) | Resection, ablation | 43.2b | – | 84.8b | – | Retrospective |

| Kunimoto (2016) [64] | Asian | Japan | IFN-based | 40 | 5.1 | 35 (87.5%) | 65 | 14 (35.0) | Resection, ablation | 23.0 (3) | 8.71 | 56.0 (3) | 27.37 | Retrospective |

| Petta (2016) [65] | Caucasian | Italy | IFN-based | 57 | 2.8 | 41 (72.0) | 62 | 0 | Resection, ablation | 15.2 (2) | 8.24 | – | – | Retrospective |

| Minami (2016) [66] | Asian | Japan | IFN-based | 38 | – | 27 (71.0) | 66 | 0 | Ablation | 52.9 (2) | 37.6 | – | – | Retrospective |

| Conti (2016) [39] | Caucasian | Italy | DAAs | 59 (including 6 non-SVR) | 0.5 | 40 (67.8) | 72 | 10 (16.9) | Resection, ablation, TACE | 28.8d (0.5) | 49.3d | – | – | Retrospective |

| Reig (2016) [40] | Caucasian | Spain | DAAs | 58 | 0.5 | 40 (69.0) | 66.3 | 5 (8.6) | Resection, ablation, TACE | 27.6d (0.5) | 47.6d | – | – | Retrospective |

| ANRS study group (2016) [42] | Caucasian | France | DAAs | 189 (including 41 non-SVR) | 2.2 | 147 (78.0) | 62a | 152 (80.0) | Resection, ablation, LT | 0.73b,d | 8.76c,d | 0.66b,e | 7.92c,e | Prospective |

| ANRS study group (2016) [42] | Caucasian | France | DAAs | 13 | 1.8 | 11 (85.0) | 61a | 13 (100) | Resection, ablation | 1.1b | 13.3c | 1.7b,e | 20.76c,e | Prospective |

| ANRS study group (2016) [42] | Caucasian | France | DAAs | 314 | – | 257 (82.0) | 61a | 49 (15.6) | LT | 2.2 (0.5) | 4.4 | – | – | Prospective |

| Petta (2016) [65] | Caucasian | Italy | DAAs | 58 | 1.5 | 40 (69.0) | 66.3 | 2 (4.0) | Resection, ablation | 26.3 (2) | 15.3 | – | – | Retrospective |

| Minami (2016) [66] | Asian | Japan | DAAs | 27 | – | 18 (67.0) | 71 | 0 | Ablation | 29.8 (2) | 17.7 | – | – | Retrospective |

When not reported, annual HCC incidence was estimated by using the declining exponential approximation of life expectancy [67]

aMean

b100 person-month

c100 person-year

dIncidence in patients including non-SVR patients

eIncidence in patients not treated by anti-HCV therapy

DAA direct-acting antiviral, HCC hepatocellular carcinoma, HCV hepatitis C virus, IFN interferon, LT liver transplantation, SVR sustained virologic response, TACE transarterial chemoembolization

Projected trend of HCV HCC incidence with new generation anti-HCV therapies

HCC is the most rapidly increasing cause of cancer death, with HCV as the major etiology affecting generally more than half of HCC patients in developed countries such as the USA [25]. HCV incidence increases are more prominent in specific subpopulations such as the 1945–1965 birth cohort (baby boomers) in the USA, in whom a 64% incidence was observed between 2003 and 2011; such an incidence is estimated to result in more than one million HCV-related cirrhosis and/or HCC by 2020, with increasing HCC incidence until 2030 [26–28]. In US veterans, HCC incidence has increased by 2.5-fold and mortality has tripled since 2001, driven overwhelmingly by HCV [29]. In a regional population in Australia, in contrast to the decreased incidence of hepatitis B virus (HBV)-related HCC due to clinical implementation of the antivirals, anti-HCV therapies had no impact on HCV-related HCC risk between 2000 and 2014 [30]. Despite the anticipated improvement in SVR rate with wider use of DAAs, model-based simulation studies have predicted further increases of HCC incidence over the next decade – even with SVR rates of 80–90% by DAAs, predicted HCC incidence will continue to increase until 2035 unless the current annual treatment uptake rate (1–3%) is increased by more than five-fold by 2018 [9, 31, 32]. These studies clearly highlight the urgent need for identification of undiagnosed HCV infection by implementing HCV screening programs targeting high-risk populations as well as improved access to new generation anti-HCV therapies with reduced costs and streamlined treatment intake and follow-up [33].

Post-SVR HCC risk factors

It is noteworthy that SVR does not necessarily mean elimination of HCC risk despite the substantially decreased incidence. In fact, HCC can occur even more than 10 years after successful HCV clearance (Table 1). The annual post-SVR HCC incidence of approximately 1% is still higher than the cancerous conditions in other organs, and the volume of HCC-developing patients will remain substantial given the vast size of the HCV-infected population [1].

Retrospective interrogation of previously treated patients mostly by interferon-based regimens revealed several post-SVR HCC-associated clinical variables, most of which are known HCC risk factors in patients with active HCV infection (Table 2). More advanced liver fibrosis as well as biochemical or imaging surrogates of histological fibrosis (e.g., serum albumin, platelet count, fibrosis-4 index, aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index, elastography-based liver stiffness) before and/or after antiviral treatment are the most prominent features associated with higher post-SVR HCC risk. Older age, alcohol abuse, accompanying metabolic disorders (especially diabetes), and persisting hepatic inflammation, e.g., high aspartate aminotransferase, were also associated with HCC risk. Serum alpha-fetoprotein levels pre- and post-SVR have also been implicated as a risk indicator, with relatively low cut-off values ranging from 5 to 20 ng/mL. In addition to the host factors, post-SVR HCC-associated pre-treatment viral factors have been identified, suggesting that HCV leads to irreversible changes in cellular signaling via mechanisms such as epigenetic activation or imprinting, which continue to drive carcinogenesis even after viral clearance. A variant in genotype 1b HCV core protein, Gln70(His70), was associated with increased HCC incidence post-SVR, with a hazard ratio of 10.5, in a cohort of 1273 interferon-treated Japanese patients [34]. Interestingly, the variant can induce cancer-related transcriptional dysregulation in an HCV-infectious cell system [35]. HCC risk association of genotype 3 was also found in a cohort of 10,817 US veterans [36]. A further study suggested differences in molecular aberrations in HCC tumors from SVR livers compared to tumors in livers with active HCV infection, which may represent SVR-specific mechanisms of carcinogenesis [37].

Table 2.

Host and viral risk factors for post-sustained virologic response (SVR) hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) development (summarized from multivariable Cox regression models)

| Risk factor | Variable | n | Country | Follow-up, median, years | Hazard ratio | 95% CI | P value | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Host factor | Fibrosis | ||||||||

| Pre-SVR | |||||||||

| Histological stage F2-4 | 562 | Japan | 4.8 | 10.7 | 2.2–192.1 | <0.001 | [53] | ||

| Histological stage, F3-4 | 1273 | Japan | 1.1 | 9.0 | 2.3–35.2 | 0.002 | [34] | ||

| Histological stage, F3-4 | 1094 | Japan | 4.2 | 3.2 | 1.6–7.2 | <0.001 | [58] | ||

| Histological stage, F3-4 | 376 | Taiwan | 7.6 | 12.8 | 1.6–101.9 | 0.021 | [56] | ||

| Histological stage, F3-4 | 871 | Taiwan | 3.4 | 4.0 | 1.5–10.7 | 0.007 | [51] | ||

| Platelet, < 150 × 103/mm3 | 1056 | Japan | 4.7 | 2.8 | 1.1–7.2 | 0.04 | [68] | ||

| Platelet, < 150 × 103/mm3 | 871 | Taiwan | 3.4 | 2.8 | 1.2–6.4 | 0.015 | [51] | ||

| Platelet, < 150 × 103/mm3 | 1000 | Europe and Canada | 5.7 | 1.1 | 1.0–1.1 | 0.029 | [61] | ||

| Albumin, < 35 g/dL | 399 | Sweden | 7.8 | 4.4 | 1.3–14.7 | 0.016 | [69] | ||

| Liver cirrhosis, yes | 1351 | Taiwan | 4.0 | 8.4 | 4.1–17.0 | <0.001 | [70] | ||

| Liver cirrhosis, yes | 4663 | Canada | 5.6 | 3.2 | 1.2–9.0 | – | [71] | ||

| Post-SVR | |||||||||

| FIB-4 index, high | 522 | Japan | 7.2 | 1.7 | 1.1–2.9 | 0.02 | [55] | ||

| APRI ≥ 0.7 | 1351 | Taiwan | 4.0 | 2.9 | 1.5–5.7 | 0.002 | [70] | ||

| Elastography liver stiffness > 12 kPa | 376 | Taiwan | 7.6 | 6.3 | 2.1–19.5 | 0.001 | [56] | ||

| Liver cirrhosis, yes | 10,738 | USA | 2.8 | 6.7 | 4.3–10.4 | <0.001 | [36] | ||

| Platelet, < 130 × 103/mm3 | 571 | Japan | 9.0 | 3.9 | 1.5–10.1 | 0.004 | [72] | ||

| Age, years | ≥50 | 562 | Japan | 4.8 | 4.1 | 1.4–17.4 | <0.01 | [53] | |

| ≥55 | 571 | Japan | 9.0 | 3.6 | 1.4–9.6 | 0.009 | [72] | ||

| ≥60 | 642 | Taiwan | 4.4 | 3.7 | 1.3–10.2 | 0.012 | [52] | ||

| ≥60 | 871 | Taiwan | 3.4 | 3.8 | 1.7–8.4 | 0.001 | [51] | ||

| ≥60 | 4663 | Canada | 5.6 | 4.4 | 1.3–15.3 | – | [71] | ||

| >60 | 1094 | Japan | 4.2 | 3.1 | 1.3–6.6 | 0.009 | [58] | ||

| >60 | 1056 | Japan | 4.7 | 3.1 | 1.3–7.4 | 0.01 | [68] | ||

| >60 | 1000 | Europe and Canada | 5.7 | 9.8 | 1.2–77.8 | 0.031 | [61] | ||

| ≥65 | 1425 | Japan | 3.3 | 5.8 | 1.1–30.1 | 0.036 | [54] | ||

| ≥65 | 1351 | Taiwan | 4.0 | 2.7 | 1.2–6.3 | 0.017 | [70] | ||

| ≥65 | 10,738 | USA | 2.8 | 4.5 | 2.0–10.4 | <0.001 | [36] | ||

| Older | 589 | Taiwan | 4.7 | 1.1 | 1.0–1.1 | 0.046 | [73] | ||

| Sex | Male | 1094 | Japan | 4.2 | 12.0 | 2.8–50.0 | <0.001 | [58] | |

| Male | 4663 | Canada | 5.6 | 3.3 | 1.1–9.6 | – | [71] | ||

| Male | 571 | Japan | 9.0 | 7.6 | 1.7–33.1 | 0.007 | [72] | ||

| Diabetes | Yes | 522 | Japan | 7.2 | 2.1 | 1.1–4.0 | 0.045 | [55] | |

| Yes | 376 | Taiwan | 7.6 | 4.0 | 1.3–12.1 | 0.021 | [56] | ||

| Yes | 399 | Sweden | 7.8 | 3.2 | 1.1–9.6 | 0.035 | [69] | ||

| Yes | 10,738 | USA | 2.8 | 1.9 | 1.2–2.9 | 0.005 | [36] | ||

| Yes | 1000 | Europe and Canada | 5.7 | 2.3 | 1.0–5.3 | 0.057 | [61] | ||

| Yes | 4663 | Canada | 5.6 | 1.6 | 0.6–4.0 | – | [71] | ||

| Yes | 589 | Taiwan | 4.7 | 3.8 | 1.4–10.1 | 0.008 | [73] | ||

| Elixhauser comorbidity index | Yes (≥1) | 4663 | Canada | 5.6 | 2.2 | 1.0–5.1 | – | [71] | |

| Alpha-fetoprotein, ng/mL | |||||||||

| Pre-SVR | ≥8 | 562 | Japan | 4.8 | 2.6 | 1.2–6.1 | <0.05 | [53] | |

| ≥15 | 1351 | Taiwan | 4.0 | 1.9 | 1.0–3.6 | 0.038 | [70] | ||

| ≥20 | 871 | Taiwan | 3.4 | 3.2 | 1.6–6.2 | 0.001 | [51] | ||

| Post-SVR | ≥5 | 1425 | Japan | 3.3 | 8.1 | 2.7–23.9 | <0.001 | [54] | |

| ≥5 | 571 | Japan | 9.0 | 3.6 | 1.4–9.6 | 0.009 | [72] | ||

| ≥15 | 1351 | Taiwan | 4.0 | 2.3 | 1.0–5.3 | 0.043 | [70] | ||

| ≥10 | 1094 | Japan | 4.2 | 7.8 | 2.9–16.8 | <0.001 | [58] | ||

| Race/ethnicity | Hispanic | 10,738 | USA | 2.8 | 2.3 | 1.1–4.8 | 0.032 | [36] | |

| Alcohol abuse | Yes | 562 | Japan | 4.8 | 3.9 | 1.7–9.0 | <0.01 | [53] | |

| Yes | 10,738 | USA | 2.8 | 1.7 | 1.1–2.6 | 0.021 | [36] | ||

| Yes | 4663 | Canada | 5.6 | 1.1 | 0.34–3.3 | – | [71] | ||

| Illicit drug use | Yes | 4663 | Canada | 5.6 | 3.7 | 1.0–14.3 | – | [71] | |

| AST | >100 IU/L | 1056 | Japan | 4.7 | 3.1 | 1.3–7.3 | 0.01 | [68] | |

| AST/ALT ratio | >0.72 | 1000 | Europe and Canada | 5.7 | 1.0 | 1.0–1.1 | 0.068 | [61] | |

| GGT | >75 U/L | 642 | Taiwan | 4.4 | 6.4 | 2.2–18.9 | 0.001 | [52] | |

| Viral factor | Genotype 1b with Gln70 (His70) variant | 1273 | Japan | 1.1 | 10.5 | 2.9–38.2 | <0.001 | [34] | |

| Genotype 3 | 10,738 | USA | 2.8 | 1.6 | 1.0–2.7 | 0.071 | [36] | ||

| Genotype 3 | 4663 | Canada | 5.6 | 1.4 | 0.58–3.4 | – | [71] |

All data are from interferon-based studies

APRI aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index, ALT alanine aminotransferase, AST aspartate aminotransferase, FIB-4 fibrosis-4, GGT gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, HCV hepatitis C virus, HCC hepatocellular carcinoma, SVR sustained virologic response

Current practice guidelines recommend regular biannual HCC screening for cirrhotic patients with active HCV infection, but it is still undetermined whether and how post-SVR patients should be monitored for future HCC development and if any of the risk-associated variables has clinical utility [1]. Molecular hallmarks of persisting HCC risk in post-SVR livers may serve as biomarkers to identify a subset of patients still at risk and should be therefore monitored by regular HCC screening. A pan-etiology HCC risk-predictive gene signature in the liver, which was shown to predict post-SVR HCC development, may serve as a biomarker to identify a subset of SVR patients who should be regularly monitored for future HCC [38].

Post-DAA HCC development and recurrence

Accumulating clinical experience of DAA-based treatment has suggested that post-SVR HCC development and recurrence may be more frequent compared to interferon-based treatment (Table 2). In a small series of HCC patients who achieved an SVR by all-oral DAAs after HCC treatment, tumor recurrence rates of approximately 30% within 6 months were reported; these rates are alarmingly high, however, the observation period was short, a proper control group was lacking, and the finding was not replicated in a subsequent study [39–43]. Further studies are needed to clarify whether DAAs increase HCC incidence and to determine the natural history and baseline post-SVR HCC incidence according to the type of anti-HCV therapy in each specific patient population. Interestingly, chronic hepatitis B patients treated with directly-acting anti-HBV drugs, entecavir or other nucleos(t)ide analogues, showed higher HCC incidence compared to peg-interferon-treated patients, suggesting that the difference in HCC-suppressive effect may be a common phenomenon across different hepatitis viruses [44].

Several studies suggested a possibly distinct difference in host immune modulation between interferon and DAAs. Rapid decline of HCV viral load by DAAs was experimentally or clinically associated with restored HCV-specific, often exhausted, CD8+ T cell function, memory T cell re-differentiation and lymphocyte deactivation, and normalized NK cell function [45–48], all of which may indicate a quick loss of anti-HCV immune responses. Interestingly, reactivation of other co-infected viruses, such as herpes virus, was observed after DAA-based anti-HCV therapy [49], suggesting simultaneous loss of bystander immune response to the viruses and possibly to neoplastic cells, which may lead to higher HCC recurrence after DAA treatment. On the other hand, complete remission of follicular lymphoma after DAA-based therapy was reported, suggesting that the influence of DAA-based SVR on cancer may vary according to cancer types and biological/clinical contexts [50].

Conclusions

HCV-related HCC will remain a major health problem in the coming decades despite the clinical deployment of DAAs. Access to the new generation antiviral therapies should be substantially improved to achieve meaningful prognostic benefit at the population level. The development of a vaccine remains an important goal for global control and eradication of infection. Post-SVR HCC is an emerging problem, with urgent unmet needs for the clinical strategy of early tumor detection and intervention, as well as elucidation of its molecular mechanisms for therapeutic target and biomarker discovery. Prolonged clinical observation should be further accumulated to determine the impact of DAA-induced SVR on HCC development and recurrence as well as on other cancer types.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge grant support of the European Union (ERC-2014-AdG-671231HEPCIR (TFB, YH), H2020-667273-HEPCAR (TFB), ANRS (TFB), the French Cancer Agency (ARC IHU201301187 (TFB)), the IdEx program of the University of Strasbourg (TFB), the Foundation University of Strasbourg (TFB), U.S. NIH/NIDDK R01 DK099558 (YH), Irma T. Hirschl Trust (YH), and U.S. Department of Defense (W81XWH-16-1-0363 YH, TFB). This work has been published under the framework of the LABEX ANR-10-LAB28 and benefits from a funding from the state managed by the French National Research Agency as part of the Investments for the future program.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

TFB, FJ, AO, and YH drafted and revised the manuscript. TFB and YH supervised the review process. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors do not have any conflict of interest and did not receive writing assistance.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Contributor Information

Thomas F. Baumert, Email: thomas.baumert@unistra.fr

Yujin Hoshida, Email: yujin.hoshida@mssm.edu.

References

- 1.Hoshida Y, Fuchs BC, Bardeesy N, Baumert TF, Chung RT. Pathogenesis and prevention of hepatitis C virus-induced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2014;61(1 Suppl):S79–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Webster DP, Klenerman P, Dusheiko GM, Hepatitis C. Lancet. 2015;385(9973):1124–35. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62401-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chung RT, Baumert TF. Curing chronic hepatitis C–the arc of a medical triumph. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(17):1576–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1400986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edlin BR. Access to treatment for hepatitis C virus infection: time to put patients first. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16(9):e196–201. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomas DL. Global control of hepatitis C: where challenge meets opportunity. Nat Med. 2013;9(7):850–8. doi: 10.1038/nm.3184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Denniston MM, Klevens RM, McQuillan GM, Jiles RB. Awareness of infection, knowledge of hepatitis C, and medical follow-up among individuals testing positive for hepatitis C: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001-2008. Hepatology. 2012;55(6):1652–61. doi: 10.1002/hep.25556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stasi C, Silvestri C, Voller F, Cipriani F. The epidemiological changes of HCV and HBV infections in the era of new antiviral therapies and the anti-HBV vaccine. J Infect Public Health. 2016;9(4):389–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2015.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chhatwal J, Wang X, Ayer T, Kabiri M, Chung RT, Hur C, Donohue JM, Roberts MS, Kanwal F. Hepatitis C disease burden in the United States in the era of oral direct-acting antivirals. Hepatology. 2016;64(5):1442–50. doi: 10.1002/hep.28571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harris RJ, Thomas B, Griffiths J, Costella A, Chapman R, Ramsay M, De Angelis D, Harris HE. Increased uptake and new therapies are needed to avert rising hepatitis C-related end stage liver disease in England: modelling the predicted impact of treatment under different scenarios. J Hepatol. 2014;61(3):530–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pawlotsky JM. Hepatitis C, virus resistance to direct-acting antiviral drugs in interferon-free regimens. Gastroenterology. 2016;151(1):70–86. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Felmlee DJ, Coilly A, Chung RT, Samuel D, Baumert TF. New perspectives for preventing hepatitis C virus liver graft infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16(6):735–45. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)00120-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fourati S, Pawlotsky JM. Virologic tools for HCV drug resistance testing. Viruses. 2015;7(12):6346–59. doi: 10.3390/v7122941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cooper C, Naggie S, Saag M, Yang JC, Stamm LM, Dvory-Sobol H, Han L, Pang PS, McHutchison JG, Dieterich D, et al. Successful re-treatment of hepatitis C virus in patients coinfected with HIV who relapsed after 12 weeks of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(4):528–31. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.European Association for the Study of the Liver EASL Recommendations on Treatment of Hepatitis C 2016. J Hepatol. 2017;66(1):153–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bukh J. The history of hepatitis C virus (HCV): Basic research reveals unique features in phylogeny, evolution and the viral life cycle with new perspectives for epidemic control. J Hepatol. 2016;65(1 Suppl):S2–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fauvelle C, Colpitts CC, Keck ZY, Pierce BG, Foung SK, Baumert TF. Hepatitis C virus vaccine candidates inducing protective neutralizing antibodies. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2016;15(12):1535–44. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2016.1194759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simmons B, Saleem J, Hill A, Riley RD, Cooke GS. Risk of late relapse or reinfection with hepatitis C virus after achieving a sustained virological response: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62(6):683–94. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gambato M, Perez-Del-Pulgar S, Hedskog C, Svarovskia ES, Brainard D, Denning J, Curry MP, Charlton M, Caro-Perez N, Londono MC, et al. Hepatitis C virus RNA persists in liver explants of most patients awaiting liver transplantation treated with an interferon-free regimen. Gastroenterology. 2016;151(4):633–6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morgan RL, Baack B, Smith BD, Yartel A, Pitasi M, Falck-Ytter Y. Eradication of hepatitis C virus infection and the development of hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(5 Pt 1):329–37. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-5-201303050-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bruno S, Di Marco V, Iavarone M, Roffi L, Crosignani A, Calvaruso V, Aghemo A, Cabibbo G, Vigano M, Boccaccio V, et al. Survival of patients with HCV cirrhosis and sustained virologic response is similar to the general population. J Hepatol. 2016;64(6):1217–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Innes H, McDonald S, Hayes P, Dillon JF, Allen S, Goldberg D, Mills PR, Barclay ST, Wilks D, Valerio H, et al. Mortality in hepatitis C patients who achieve a sustained viral response compared to the general population. J Hepatol. 2017;66(1):19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lok AS, Everhart JE, Wright EC, Di Bisceglie AM, Kim HY, Sterling RK, Everson GT, Lindsay KL, Lee WM, Bonkovsky HL, et al. Associated with hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with advanced hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2011;140(3):840–9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.11.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nahon P, Bourcier V, Layese R, Audureau E, Cagnot C, Marcellin P, Guyader D, Fontaine H, Larrey D, De Ledinghen V, et al. Eradication of hepatitis C virus infection in patients with cirrhosis reduces risk of liver and non-liver complications. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(1):142–6.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheung MC, Walker AJ, Hudson BE, Verma S, McLauchlan J, Mutimer DJ, Brown A, Gelson WT, MacDonald DC, Agarwal K, et al. Outcomes after successful direct-acting antiviral therapy for patients with chronic hepatitis C and decompensated cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2016;65(4):741–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.El-Serag HB, Kanwal F. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States: Where are we? Where do we go? Hepatology. 2014;60(5):1767–75. doi: 10.1002/hep.27222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jacobson IM, Davis GL, El-Serag H, Negro F, Trepo C. Prevalence and challenges of liver diseases in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8(11):924–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yan M, Ha J, Aguilar M, Bhuket T, Liu B, Gish RG, Cheung R, Wong RJ. Birth cohort-specific disparities in hepatocellular carcinoma stage at diagnosis, treatment, and long-term survival. J Hepatol. 2016;64(2):326–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Petrick JL, Kelly SP, Altekruse SF, McGlynn KA, Rosenberg PS. Future of hepatocellular carcinoma incidence in the United States forecast through 2030. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(15):1787–94. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.7412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beste LA, Leipertz SL, Green PK, Dominitz JA, Ross D, Ioannou GN. Trends in burden of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma by underlying liver disease in US veterans, 2001-2013. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(6):1471–82.e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.07.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Waziry R, Grebely J, Amin J, Alavi M, Hajarizadeh B, George J, Matthews GV, Law M, Dore GJ. Trends in hepatocellular carcinoma among people with HBV or HCV notification in Australia (2000-2014) J Hepatol. 2016;65(6):1086–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sievert W, Razavi H, Estes C, Thompson AJ, Zekry A, Roberts SK, Dore GJ. Enhanced antiviral treatment efficacy and uptake in preventing the rising burden of hepatitis C-related liver disease and costs in Australia. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29(Suppl 1):1–9. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cramp ME, Rosenberg WM. Ryder SD1, Blach S. Parkes J. Modelling the impact of improving screening and treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus infection on future hepatocellular carcinoma rates and liver-related mortality. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014;14:137. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-14-137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Asselah T, Perumalswami PV, Dieterich D. Is screening baby boomers for HCV enough? A call to screen for hepatitis C virus in persons from countries of high endemicity. Liver Int. 2014;34(10):1447–51. doi: 10.1111/liv.12599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Akuta N, Suzuki F, Hirakawa M, Kawamura Y, Sezaki H, Suzuki Y, Hosaka T, Kobayashi M, Kobayashi M, Saitoh S, et al. Amino acid substitutions in hepatitis C virus core region predict hepatocarcinogenesis following eradication of HCV RNA by antiviral therapy. J Med Virol. 2011;83(6):1016–22. doi: 10.1002/jmv.22094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.El-Shamy A, Eng FJ, Doyle EH, Klepper AL, Sun X, Sangiovanni A, Iavarone M, Colombo M, Schwartz RE, Hoshida Y, et al. A cell culture system for distinguishing hepatitis C viruses with and without liver cancer-related mutations in the viral core gene. J Hepatol. 2015;63(6):1323–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.El-Serag HB, Kanwal F, Richardson P, Kramer J. Risk of hepatocellular carcinoma after sustained virological response in veterans with hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology. 2016;64(1):130–7. doi: 10.1002/hep.28535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hayashi T, Tamori A, Nishikawa M, Morikawa H, Enomoto M, Sakaguchi H, Habu D, Kawada N, Kubo S, Nishiguchi S, et al. Differences in molecular alterations of hepatocellular carcinoma between patients with a sustained virological response and those with hepatitis C virus infection. Liver Int. 2009;29(1):126–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakagawa S, Wei L, Song W, Higashi T, Ghoshal S, Kim RS, Bian CB, Yamada S, Sun X, Venkatesh A, et al. Molecular liver cancer prevention in cirrhosis by organ transcriptome analysis and lysophosphatidic acid pathway inhibition. Cancer Cell. 2016;30(6):879–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Conti F, Buonfiglioli F, Scuteri A, Crespi C, Bolondi L, Caraceni P, Foschi FG, Lenzi M, Mazzella G, Verucchi G, et al. Early occurrence and recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma in HCV-related cirrhosis treated with direct-acting antivirals. J Hepatol. 2016;65(4):727–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reig M, Marino Z, Perello C, Inarrairaegui M, Ribeiro A, Lens S, Diaz A, Vilana R, Darnell A, Varela M, et al. Unexpected high rate of early tumor recurrence in patients with HCV-related HCC undergoing interferon-free therapy. J Hepatol. 2016;65(4):719–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang JD, Aqel BA, Pungpapong S, Gores GJ, Roberts LR, Leise MD. Direct acting antiviral therapy and tumor recurrence after liver transplantation for hepatitis C-associated hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2016;65(4):859–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.ANRS collaborative study group on hepatocellular carcinoma (ANRS CO22 HEPATHER, CO12 CirVir and CO23 CUPILT cohorts) Lack of evidence of an effect of direct-acting antivirals on the recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma: Data from three ANRS cohorts. J Hepatol. 2016;65(4):734–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.05.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kozbial K, Moser S, Schwarzer R, Laferl H, Al-Zoairy R, Stauber R, Stattermayer AF, Beinhardt S, Graziadei I, Freissmuth C, et al. Unexpected high incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic patients with sustained virologic response following interferon-free direct-acting antiviral treatment. J Hepatol. 2016;65(4):856–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liang KH, Hsu CW, Chang ML, Chen YC, Lai MW, Yeh CT. Peginterferon is superior to nucleos(t)ide analogues for prevention of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B. J Infect Dis. 2016;213(6):966–74. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martin B, Hennecke N, Lohmann V, Kayser A, Neumann-Haefelin C, Kukolj G, Bocher WO, Thimme R. Restoration of HCV-specific CD8+ T cell function by interferon-free therapy. J Hepatol. 2014;61(3):538–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Burchill MA, Golden-Mason L, Wind-Rotolo M, Rosen HR. Memory re-differentiation and reduced lymphocyte activation in chronic HCV-infected patients receiving direct-acting antivirals. J Viral Hepat. 2015;22(12):983–91. doi: 10.1111/jvh.12465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spaan M, van Oord G, Kreefft K, Hou J, Hansen BE, Janssen HL, de Knegt RJ, Boonstra A. Immunological analysis during interferon-free therapy for chronic hepatitis c virus infection reveals modulation of the natural killer cell compartment. J Infect Dis. 2016;213(2):216–23. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Serti E, Chepa-Lotrea X, Kim YJ, Keane M, Fryzek N, Liang TJ, Ghany M, Rehermann B. Successful interferon-free therapy of chronic hepatitis C virus infection normalizes natural killer cell function. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(1):190–200.e192. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Perello MC, Fernandez-Carrillo C, Londono MC, Arias-Loste T, Hernandez-Conde M, Llerena S, Crespo J, Forns X, Calleja JL. Reactivation of herpesvirus in patients with hepatitis C treated with direct-acting antiviral agents. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(11):1662–6.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maciocia N, O'Brien A, Ardeshna K. Remission of follicular lymphoma after treatment for hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(17):1699–701. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1513288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chang KC, Hung CH, Lu SN, Wang JH, Lee CM, Chen CH, Yen MF, Lin SC, Yen YH, Tsai MC, et al. A novel predictive score for hepatocellular carcinoma development in patients with chronic hepatitis C after sustained response to pegylated interferon and ribavirin combination therapy. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67(11):2766–72. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huang CF, Yeh ML, Tsai PC, Hsieh MH, Yang HL, Hsieh MY, Yang JF, Lin ZY, Chen SC, Wang LY, et al. Baseline gamma-glutamyl transferase levels strongly correlate with hepatocellular carcinoma development in non-cirrhotic patients with successful hepatitis C virus eradication. J Hepatol. 2014;61(1):67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yamashita N, Ohho A, Yamasaki A, Kurokawa M, Kotoh K, Kajiwara E. Hepatocarcinogenesis in chronic hepatitis C patients achieving a sustained virological response to interferon: significance of lifelong periodic cancer screening for improving outcomes. J Gastroenterol. 2014;49(11):1504–13. doi: 10.1007/s00535-013-0921-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Oze T, Hiramatsu N, Yakushijin T, Miyazaki M, Yamada A, Oshita M, Hagiwara H, Mita E, Ito T, Fukui H, et al. Post-treatment levels of alpha-fetoprotein predict incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma after interferon therapy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(7):1186–95. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Toyoda H, Kumada T, Tada T, Kiriyama S, Tanikawa M, Hisanaga Y, Kanamori A, Kitabatake S, Ito T. Risk factors of hepatocellular carcinoma development in non-cirrhotic patients with sustained virologic response for chronic hepatitis C virus infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30(7):1183–9. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang JH, Yen YH, Yao CC, Hung CH, Chen CH, Hu TH, Lee CM, Lu SN. Liver stiffness-based score in hepatoma risk assessment for chronic hepatitis C patients after successful antiviral therapy. Liver Int. 2016;36(12):1793–9. doi: 10.1111/liv.13179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kobayashi M, Suzuki F, Fujiyama S, Kawamura Y, Sezaki H, Hosaka T, Akuta N, Suzuki Y, Saitoh S, Arase Y, et al. Sustained virologic response by direct antiviral agents reduces the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with HCV infection. J Med Virol. 2016;89(3):476–83. doi: 10.1002/jmv.24663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nagaoki Y, Aikata H, Nakano N, Shinohara F, Nakamura Y, Hatooka M, Morio K, Kan H, Fujino H, Kobayashi T, et al. Development of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with hepatitis C virus infection who achieved sustained virological response following interferon therapy: a large-scale, long-term cohort study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31(5):1009–15. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tada T, Kumada T, Toyoda H, Kiriyama S, Tanikawa M, Hisanaga Y, Kanamori A, Kitabatake S, Yama T, Tanaka J. Viral eradication reduces all-cause mortality in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection: a propensity score analysis. Liver Int. 2016;36(6):817–26. doi: 10.1111/liv.13071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tada T, Kumada T, Toyoda H, Kiriyama S, Tanikawa M, Hisanaga Y, Kanamori A, Kitabatake S, Yama T, Tanaka J. Viral eradication reduces all-cause mortality, including non-liver-related disease, in patients with progressive hepatitis C virus-related fibrosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 doi: 10.1111/jgh.13589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.van der Meer AJ, Feld JJ, Hofer H, Almasio PL, Calvaruso V, Fernandez-Rodriguez CM, Aleman S, Ganne-Carrie N, D'Ambrosio R, Pol S, et al. Risk of cirrhosis-related complications in patients with advanced fibrosis following hepatitis C virus eradication. J Hepatol. 2017;66(3):485–93. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 62.Saito T, Chiba T, Suzuki E, Shinozaki M, Goto N, Kanogawa N, Motoyama T, Ogasawara S, Ooka Y, Tawada A, et al. Effect of previous interferon-based therapy on recurrence after curative treatment of hepatitis C virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Med Sci. 2014;11(7):707–12. doi: 10.7150/ijms.8764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Huang JF, Yeh ML, Yu ML, Dai CY, Huang CF, Huang CI, Tsai PC, Lin PC, Chen YL, Chang WT, et al. The tertiary prevention of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis C patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30(12):1768–74. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kunimoto H, Ikeda K, Sorin Y, Fujiyama S, Kawamura Y, Kobayashi M, Sezaki H, Hosaka T, Akuta N, Saitoh S, et al. Long-term outcomes of hepatitis-c-infected patients achieving a sustained virological response and undergoing radical treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncology. 2016;90(3):167–75. doi: 10.1159/000443891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Petta S, Cabibbo G, Barbara M, Attardo S, Bucci L, Farinati F, Giannini EG, Tovoli F, Ciccarese F, Rapaccini GL, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence in patients with curative resection or ablation: impact of HCV eradication does not depend on the use of interferon. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45(1):160–8. doi: 10.1111/apt.13821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Minami T, Tateishi R, Nakagomi R, Fujiwara N, Sato M, Enooku K, Nakagawa H, Asaoka Y, Kondo Y, Shiina S, et al. The impact of direct-acting antivirals on early tumor recurrence after radiofrequency ablation in hepatitis C-related hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2016;65(6):1272–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Beck JR, Kassirer JP, Pauker SG. A convenient approximation of life expectancy (the “DEALE”): I. Validation of the method. Am J Med. 1982;73(6):883–8. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(82)90786-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ikeda M, Fujiyama S, Tanaka M, Sata M, Ide T, Yatsuhashi H, Watanabe H. Risk factors for development of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic hepatitis C after sustained response to interferon. J Gastroenterol. 2005;40(2):148–56. doi: 10.1007/s00535-004-1519-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hedenstierna M, Nangarhari A, Weiland O, Aleman S. Diabetes and cirrhosis are risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma after successful treatment of chronic hepatitis C. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(6):723–9. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wu CK, Chang KC, Hung CH, Tseng PL, Lu SN, Chen CH, Wang JH, Lee CM, Tsai MC, Lin MT, et al. Dynamic alpha-fetoprotein, platelets and AST-to-platelet ratio index predict hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis C patients with sustained virological response after antiviral therapy. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71(7):1943–7. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Janjua NZ, Chong M, Kuo M, Woods R, Wong J, Yoshida EM, Sherman M, Butt ZA, Samji H, Cook D, et al. Long-term effect of sustained virological response on hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with hepatitis C in Canada. J Hepatol. 2017;66(3):504–13. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 72.Tada T, Kumada T, Toyoda H, Kiriyama S, Tanikawa M, Hisanaga Y, Kanamori A, Kitabatake S, Yama T, Tanaka J. Post-treatment levels of alpha-fetoprotein predict long-term hepatocellular carcinoma development after sustained virological response in patients with hepatitis C. Hepatol Res. 2016 doi: 10.1111/hepr.12839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Huang CF, Yeh ML, Huang CY, Tsai PC, Ko YM, Chen KY, Lin ZY, Chen SC, Dai CY, Chuang WL, et al. Pretreatment glucose status determines HCC development in HCV patients with mild liver disease after curative antiviral therapy. Medicine. 2016;95(27) doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.