Abstract

Background

Rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder (RBD) may present as an early manifestation of an evolving neurodegenerative disorder with alpha-synucleinopathy.

Objective

We investigated that dementia with RBD might show distinctive cortical atrophic patterns.

Methods

A total of 31 patients with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease (IPD), 23 with clinically probable Alzheimer’s disease (AD), and 36 healthy controls participated in this study. Patients with AD and IPD were divided into two groups according to results of polysomnography and rated with a validated Korean version of the RBD screening questionnaire (RBDSQ-K), which covers the clinical features of RBD. Voxel-based morphometry was adapted for detection of regional brain atrophy among groups of subjects.

Results

Scores on RBDSQ-K were higher in the IPD group (3.54 ± 2.8) than in any other group (AD, 2.94 ± 2.4; healthy controls, 2.31 ± 1.9). Atrophic changes according to RBDSQ-K scores were characteristically in the posterior part of the brain and brain stem, including the hypothalamus and posterior temporal region including the hippocampus and bilateral occipital lobe. AD patients with RBD showed more specialized atrophic patterns distributed in the posterior and inferior parts of the brain including the bilateral temporal and occipital cortices compared to groups without RBD. The IPD group with RBD showed right temporal cortical atrophic changes.

Conclusion

The group of patients with neurodegenerative diseases and RBD showed distinctive brain atrophy patterns, especially in the posterior and inferior cortices. These results suggest that patients diagnosed with clinically probable AD or IPD might have mixed pathologies including α-synucleinopathy.

Keywords: Brain atrophy, dementia, RBD screening questionnaire, REM sleep disorder, voxel-based morphometry

INTRODUCTION

Rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder (RBD) is parasomnia characterized by dream-enhancement occurring in rapid eye movement sleep [1, 2]. RBD is frequently referred to as an early sign of a slowly evolving neurodegenerative disorder or a long-term predictor of it [3]. Some studies reported specific anatomical regions related with RBD, including the dysfunction of a network among the midbrain and pontine tegmentum, the locus subcoeruleus, the medullary magnocellular reticular formation, and focal lesions of the pontine or mesencephalic tegmentum [4, 5]. Recent long-term prospective studies have shown that 30% to 65% of patients with idiopathic RBD will eventually develop a neurodegenerative disorder associated with alpha-synuclein pathology such as idiopathic Parkinson’s disease (IPD), multiple system atrophy, or diffuse Lewy body disease with dementia (DLB) depending on the length of follow-up [1]. Idiopathic RBD may present as an early manifestation of an evolving neurodegenerative disorder with alpha-synucleinopathy [6]. A diffusion-tensor imaging and voxel-based morphometry (VBM) study localized two areas harboring key neuronal circuits involved in the regulation of REM sleep in the pontomesencephalic brainstem, and these were overlapped with areas of structural brainstem damage causing symptomatic idiopathic RBD in humans [7]. In contrast to idiopathic RBD, secondary RBD showed special association with the synucleinopathies in terms of both structural and time sequence in the brain, explaining the evolution of parkinsonism and/or dementia well after the onset of RBD [8].

The relationship between MRI pathology and patients with secondary RBD who develop alpha-synuclein–related neurodegenerative diseases has rarely been reported [9–11]. In several autopsy series, more than half of patients with Lewy-related pathology, including Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites, had concomitant Alzheimer pathology [12–15]. We postulated that dementia with RBD might show distinctive cortical or subcortical atrophy patterns compared to Alzheimer’s dementia (AD) and IPD without RBD. Participants were divided into two groups, those with RBD and those without RBD based on polysomnography, and then compared cortical and subcortical atrophic patterns using voxel-based morphometry in these patients. The purpose of this study was to evaluate brain atrophy patterns in patients with RBD in neurodegenerative disorder compared to those without RBD.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Subjects

A total of 31 patients with IPD and 23 patients with AD aged 55–80 years were prospectively recruited from the Department of Neurology at Hanyang University between June 2014 and Nov 2014. AD was diagnosed using criteria developed by the National Institute of Neurologic and Communicative Disorders and Stroke-Alzheimer Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCD-ADRDA) [16]. We excluded patients with 1) secondary dementia or parkinsonism, such as a brain tumor or encephalitis; 2) a diagnosis of psychiatric illness within two years; 3) another medical disease causing cognitive dysfunction (liver disease, renal disease, thyroid disease); and 4) alcohol or drug addiction diagnosed within two years. For all the IPD patients, diagnosis of PD was made according to the UK Parkinson’s Disease Society Brain Bank criteria [17]. We enrolled patients with IPD who met the following criteria: 1) age 40–70 years; 2) short disease duration (one to five years from diagnosis); 3) Hoehn and Yahr stage ≤ 3 [18]; 4) no dementia (not fulfilling the DSM-IV-TR [19] dementia criteria) or prior clinical suspicion of cognitive impairment and no subjective memory impairment at interview; 5) without signs or symptoms suggestive of secondary parkinsonism or atypical parkinsonism such as multiple system atrophy. Thirty six age-matched healthy controls without any medical illness were enrolled and underwent brain MRI. All participants were also administered the standard Korean version of the Mini-Mental State Examination (K-MMSE) and the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) to compare cognition and clinical state [20, 21].

The study was approved by the ethics committees of Hanyang University, and participants provided written informed consent according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Evaluation of REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD)

All patients with AD and IPD were divided into two group according to result of polysomnography (PSG). The Korean version of the REM sleep behavior disorder screening questionnaire (RBDSQ-K) was used to measure the severity of RBD [22]. The RBDSQ-K consists of a total of 13 items, and answers were provided as “Yes – 1,” or “No – 0” and “I do not know – 0” by the patient or their spouse. Total scores ranged from 0 to 13 points. The RBDSQ-K was performed on all participants.

Imaging

MRI scans were obtained on a 3.0-T Achieva system (Phillips) equipped with a standard quadrature head coil. Structural MRI sequences included a volumetric three-dimensional spoiled fast gradient echo MRI (repetition time (TR), 7.3; echo time (TE), 2.7 ms; slice thickness, 1.0 mm; flip angle, 13°; field of view of 256 mm × 256 mm; the volume consisted of 200 contiguous coronal sections covering the whole brain.

Voxel-based morphometry (VBM)

VBM is a fully automated, whole-brain technique for the detection of regional brain atrophy by voxel-wise comparison of gray and white matter volumes between groups of subjects. The technique comprises a spatial preprocessing step (spatial normalization, segmentation, modulation and smoothing) followed by statistical analysis. Both stages were implemented using the Statistical Parametric Mapping 5 software package (SPM5, Functional Imaging Laboratory, Wellcome Department of Imaging Neuroscience, Institute of Neurology, UCL, UK; http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm). Patients’ and controls’ images were normalized to the common template to allow inter-subject comparisons and then segmented into gray, white, and CSF compartments using the VBM technique. Segmented and modulated images were transformed into MNI space and smoothed by a Gaussian kernel of 12 × 12 × 12 mm.

Statistical analysis

SPSS (v. 22.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analyses. Comparisons of patient demographics, RBDSQ-K, MMSE, and CDR among the AD, IPD, and healthy control subjects were assessed by ANOVA with post hoc analyses. p-values less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Independent t-test analysis was used to compare atrophy between the control and patient group. Patients in the AD and IPD groups with different atrophic patterns were divided into two groups according PSG and compared using independent t-test analysis. The degree of atrophy was compared in AD and IPD with RBD by multiple regression analyses according to RBDSQ-K scores. All analyses were performed using the SPM5 statistical package.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

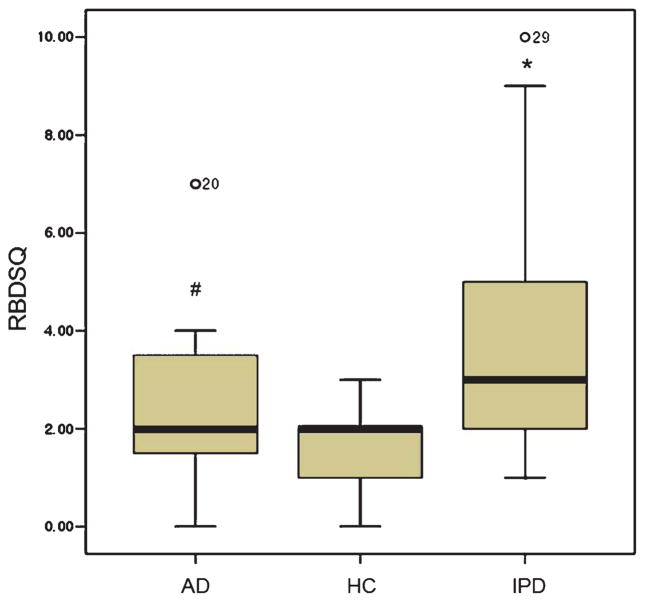

The mean patient age was 74.6 ± 7.2 years, 63.9 ± 10.8 years, and 50.4 ± 4.8 years for the AD, IPD, and control groups, respectively. Disease duration was short (one to five years from diagnosis). K-MMSE score was the lowest (20.1 ± 4.5) in AD, followed by the IPD (22.6 ± 4.3) and control (24.2 ± 4.3) groups. The level of education according to K-MMSE score differed in each of the target groups (Table 1). The average RBDSQ-K score was highest in patients with IPD (3.70 ± 2.4), and AD group had a higher score than the control group (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Participant demographics

| Healthy controls (n = 36) | AD (n = 23) | IPD (n = 31) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y)* | 72.9 ± 5.7 | 71.6 ± 8.1 | 68.4 ± 7.9 | 0.075 |

| Female (%) | 17 (47.2) | 14 (60.9) | 20 (74.1) | 0.4 |

| Education (y)* | 4.8 ± 3.7 | 6.4 ± 6.0 | 6.7 ± 5.4 | 0.58 |

| K-MMSE* | 29.3 ± 1.2 | 20.1 ± 4.5 | 22.6 ± 4.3 | 0.006 |

| CDR* | 0 | 0.91 ± 0.47 | 0.44 ± 0.32 | <0.001 |

Value is mean ± SD.

AD, Alzheimer’s disease; IPD, idiopathic Parkinson’s disease; K-MMSE, Korean version of the Mini-Mental Status Examination; CDR, clinical dementia rating scale; y, years.

Fig. 1.

Participant RBDSQ-K scores. The average RBDSQ-K score of patients with IPD was the highest (3.70 ± 2.4), followed by the AD group, which had a higher average score than that of the controls. AD, Alzheimer’s disease; IPD, idiopathic Parkinson’s disease; HC, healthy controls; RBD, REM sleep behavior disorder; RBDSQ-K, Korean version of RBD Screening Questionnaire. *p < 0.001 and #p = 0.039 on the Kruskal-Wallis test.

Cortical and subcortical changes in AD and IPD

Cortex atrophy in the bilateral parieto-temporal and frontal areas was observed in AD patients compared to controls (family-wise error (FWE) correction p < 0.05; Fig. 2A). Patients with IPD showed focal cortical atrophy in the bilateral dorsolateral frontal and right-dominant frontal cortices compared to controls (uncorrected p < 0.001; Fig. 2B). There was no cortical atrophic change in IPD on corrected analysis. There was no significant atrophic change within the subcortices of AD and IPD patients when compared to controls.

Fig. 2.

Cortical atrophy on group analysis. A) The AD group showed bilateral parieto-temporal cortex and bilateral frontal cortex atrophy compared to controls (FWE p < 0.05). B) The IPD group had bilateral frontal cortical atrophic changes compared to controls (uncorrected p < 0.001). AD, Alzheimer’s disease; IPD, idiopathic Parkinson’s disease; RBD, REM sleep behavior disorder; FWE, family-wise error.

Cortical and subcortical changes according to RBDSQ-K scores

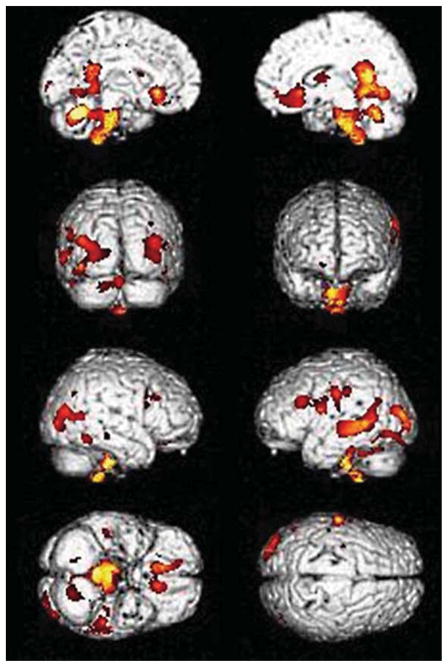

We evaluated the findings of structural MRI using VBM according to RBDSQ-K scores using multiple regression with a threshold of uncorrected p < 0.001 adjusting for age, sex, and total intracranial volume correction at a cluster level of 100 voxels. Atrophic changes were characteristically in the posterior part of the brain and brain stem, including the hypothalamus, and the posterior temporal region, including the hippocampus and bilateral occipital lobes. The three-dimensional surface rendering maps demonstrated greater atrophy in the posterior cingulate, precuneus, lateral parietal, and posterior temporal cortex, both occipital, posterior cingulate, precuneus, both inferior frontal cortices, and the brain stem, including the hypothalamus (uncorrected p < 0.001; Fig. 3.). These findings disappeared when we used a threshold of 0.05, correcting for multiple variables using FWE. We did not find greater atrophy in subcortical structures.

Fig. 3.

Brain atrophic changes according to RBDSQ-K score. The three-dimensional surface rendering maps demonstrated greater atrophy in the posterior cingulate, precuneus, lateral parietal and posterior temporal cortex, both occipital, both inferior frontal cortices and the brain stem, including hypothalamus atrophy. The coronal section from the custom template demonstrated asymmetric right-greater-than-left atrophy in the posterior temporal regions on multiple regression in SPM5 (uncorrected p < 0.001). RBD, REM sleep behavior disorder; RBDSQ-K, Korean version of RBD Screening Questionnaire.

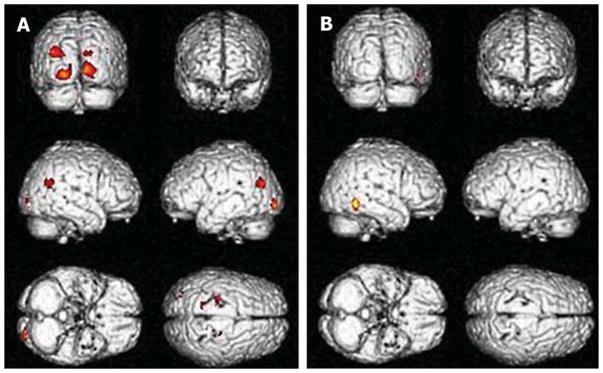

Cortical and subcortical changes in AD and IPD according to RBD status

AD and IPD patients were divided into two groups with RBD and without RBD, and the severity was measured using RBDSQ-K scores. Patient demographics are summarized in Table 2. There were significant differences in RBDSQ-K scores and level of education in both the AD and IPD group, according to existence of RBD. The AD group with RBD showed more progressive clinical symptoms with low K-MMSE, high CDR, and disease duration than those without RBD. Distinctive cortical atrophic patterns were observed in patients with RBD in both the AD and IPD groups. Those in the AD group who were determined to have a high likelihood of having RBD showed cortical atrophic patterns in both occipito-temporal regions when using a threshold of uncorrected p < 0.001 adjusting for age, sex, and total intracranial volume correction at a cluster level of 100 voxels (Fig. 4A, Table 3). Those in the IPD group showed atrophy in the right inferior posterior temporal area (Fig. 4B, Table 3; uncorrected p < 0.001). These findings disappeared when we used a threshold of 0.05 after correcting for multiple comparisons using FWE. There were no positive results in subcortical structure.

Table 2.

Demographics in AD and IPD according to the presence of RBD

| AD without RBD (n = 14) | AD with RBD (n = 9) | IPD without RBD (n = 22) | IPD with RBD (n = 9) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y)* | 67.7 ± 8.4 | 70.1 ± 6.9 | 67.7 ± 8.4 | 70.1 ± 6.8 |

| Female (%) | 8 (57.1) | 6 (66.7) | 12 (54.5) | 9 (100) |

| Education (y)* | 8.6 ± 5.1† | 2.0 ± 2.5† | 8.5 ± 4.8† | 2.4 ± 2.5† |

| Disease duration (y) | 1.7 ± 1.2 | 1.9 ± 1.3 | 1.9 ± 1.4 | 1.9 ± 1.5 |

| RBDSQ-K score* | 1.9 ± 1.5† | 6.2 ± 1.5† | 2.0 ± 1.2† | 7.8 ± 1.8† |

| K-MMSE* | 22.9 ± 4.5 | 17.3 ± 6.0 | 22.9 ± 4.3 | 22.1 ± 3.5 |

| CDR* | 0.41 ± 0.37 | 0.91 ± 0.47 | 0.44 ± 0.36 | 0.43 ± 0.16 |

Value is mean ± SD;

p = 0.05 on the Kruskal-Wallis test.

AD, Alzheimer’s disease; IPD, idiopathic Parkinson’s disease; RBD, REM sleep behavior disorder; RBDSQ-K, Korean version of RBD Screening Questionnaire; K-MMSE, Korean version of Mini-Mental Status Examination; CDR, clinical dementia rating scale; y, years.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of regional atrophic patterns according to the presence of RBD in AD and IPD with RBD compared to those without RBD. The three-dimensional surface rendering maps demonstrated greater atrophy in the bilateral occipital and right superior temporal, and both posterior central gyri in the coronal section on custom two sample t-tests in SPM5 (uncorrected p < 0.001, T-score 2.62 in AD versus 3.48 in IPD). AD, Alzheimer’s disease; IPD, idiopathic Parkinson’s disease; RBD, REM sleep behavior disorder.

Table 3.

Relative decrease in gray matter in AD and IPD patients with RBD compared to those without RBD

| AD (with RBD > without RBD) | MNI-space

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Side | Clusters | x | y | z | T-value | p-value | |

| Atrophic regions | |||||||

| Precuneus | Right | 139 | −8 | −52 | 51 | 5.39 | 0.083 |

| Middle occipital | Left | 140 | −27 | −71 | 30 | 5.2 | 0.002 |

| Cuneus | Right | 107 | 66 | −2 | 38 | 4.53 | 0.001 |

| Lingual | Right | 561 | 13 | −81 | 1 | 4.83 | 0.005 |

| Lingual | Left | 561 | −15 | −66 | −2 | 4.21 | 0.005 |

| Calcarine | Right | 590 | 10 | −66 | 17 | 4.26 | 0.004 |

| Superior temporal | Right | 202 | 46 | −31 | 16 | 4.2 | 0.068 |

| Superior parietal | Left | 215 | −34 | 59 | 60 | 4.04 | 0.06 |

| Superior parietal | Left | 139 | −34 | 59 | 60 | 3.91 | 0.07 |

| Postcentral | Right | 137 | −15 | −66 | −2 | 3.58 | 0.125 |

| IPD with RBD (with RBD>without RBD) | |||||||

| Superior temporal | Right | 114 | 62 | −8 | 8 | 4.56 | 0.001 |

AD, Alzheimer’s disease; IPD, idiopathic Parkinson’s disease; RBD, REM sleep behavior disorder.

DISCUSSION

We analyzed brain structure differences in neurodegenerative disorders according to the presence of RBD. The results of this study can be summarized as follows: (1) The IPD group had the greatest number of RBD symptoms, but some symptoms were also present in the AD group; (2) there were specific atrophic patterns in cortical structures in the AD and IPD groups, specifically the bilateral occipital, right temporoparietal and focal frontal areas; (3) bilateral occipital cortical atrophic changes were observed in patients with AD and RBD; and (4) right temporal atrophic changes were observed in patients with IPD and RBD. Many researchers have reported that RBD is a manifestation of alpha-synuclein pathology, and not only is the incidence greater in AD, such as dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) [23], but the presence of RBD may also improve diagnostic accuracy [24]. One study reported that idiopathic RBD could be assumed to be a sign of alpha-synucleinopathy [2], and patients with neurodegenerative disease showed increased muscle activity during REM sleep on polysomnography without overt RBD signs and symptoms [25]. Some studies reported that RBD appears years or decades before diagnosis of IPD, MSA, DLB or Parkinson’s disease with dementia [1, 2, 8, 26]. Delayed emergence of parkinsonian disorder was reported in 38% of 29 older men initially diagnosed with idiopathic RBD [27]. It is important to determine whether the existence of RBD is necessary for the early diagnosis and management of patients with neurodegenerative disease.

Anatomical substrates of RBD associated with structural lesions in the brain stem have been reported; the dorsal midbrain and pons have been implicated based on human cases [8]. Pathophysiologic studies found that RBD is associated with brain-stem structures such as the peri-locus ceruleus area in animal studies [28, 29]. However, there may be differences in pathologic substrates between idiopathic and secondary RBD.

In this study, we compared the clinical characteristics and degree of atrophy among patients with neurodegenerative disease who had been divided into two groups according to the presence of RBD. There were significant differences in RBDSQ-K scores and education level in both the AD and IPD groups. Patients with AD and RBD showed distinctive atrophic patterns in the cortical structure of bilateral occipital regions. These results suggest that RBD symptoms are correlated with atrophic changes in specific areas such as the temporo-occipital areas, and this might be related to the accumulation of cortical synuclein in AD or clinically probable AD (including pathologically proven DLB) as previously reported [14, 23]. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that the cortical atrophy itself may be the source of RBD in AD. Our comparison between groups of patients with AD and IPD revealed that there were differences between groups in terms of MMSE, CDR and disease duration, although they were not statistically significant.

Patients with RBD symptoms and IPD showed atrophic patterns in the right temporal regions in this analysis. This finding is consistent with a previous study in which the authors used diffusion tensor imaging and found significant microstructural changes in the white matter of the brainstem (uncorrected P < 0.001), the right substantia nigra, the olfactory region, the left temporal lobe, the fornix, the internal capsule, the corona radiata, and the right visual stream of patients with iRBD [20]. The temporal cortex takes charge in spatial cognition in humans, thus right temporal cortical atrophic changes would be related to RBD symptoms in IPD. We did not find any abnormalities in white matter structure using VBM analysis. A recent study revealed reduced signal intensity in the locus coeruleus/subcoeruleus area in patients with IPD that was more marked in patients with than those without RBD [30]. This discrepancy in findings might be due to differences in method used to identify white matter structure disruptions [31].

This study was limited by the fact that RBD severity was assessed using only RBDSQ-K scores and not polysomnography. A definite diagnosis could be achieved only with a PSG recording. The relationship between the severity of RBD and various features is supported by PSG findings indicating a loss of REM sleep muscle atonia and/or excessive phasic muscle twitching and actual observation of RBD occurrences [32]. While polysomnography contains much more information and is essential for the diagnosis of RBD, assessing the severity of RBD with polysomnographic measures, including electromyographic activities [33], qualitative and quantitative video polysomnography [34, 35], takes much time and effort, making it thus less feasible for practical uses. Using the REM Sleep Behavior Disorder Severity Scale (RBDSS), a more simplified tool, has been suggested, but still needs more validation [36]. Although previous studies reported that there was no significant correlation between RBDSQ-K score and duration or severity of RBD symptoms [22, 37], it is the most widely used and easily applicable in an individual clinical study, so we focused on using the more practical scale to see the relevance.

Another limitation of this study is that polysomnography was not performed in the healthy control group. According to a recent study, the prevalence of RBD was reported to be 7.7% in an elderly cohort [38], and thus it is possible that some of the controls had RBD. Furthermore, the proportion of female participants was high compared to other studies, specifically in IPD. Thus selection bias may have affected our results.

Finally, we failed to demonstrate significant results even after correcting our analysis by FWE or FDR, although our findings were significant when the data were analyzed using the uncorrected method. This may be because all included participants were in a stage of disease too early to be detected. It is possible that the neural substrate of secondary RBD is in the white matter. The recommended method for assessing white matter is diffusion tensor imaging or magnetization transfer in order to better describe and understand the histopathological correlation with lesions [39].

The results of our study suggest that the anatomical location of secondary RBD may differ according to the primary pathological neurodegenerative disease. Different cortical atrophic changes might be related to the presence of synucleinopathy in primary neurode-generative disorders. Diagnosis of RBD at an early stage will be helpful in determining the prognosis of neurodegenerative diseases and treatment.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

Authors’ disclosures are available online (http://j-alz.com/manuscript-disclosures/15-1197r1).

References

- 1.Boeve BF, Silber MH, Ferman TJ, Kokmen E, Smith GE, Ivnik RJ, Parisi JE, Olson EJ, Petersen RC. REM sleep behavior disorder and degenerative dementia: An association likely reflecting Lewy body disease. Neurology. 1998;51:363–370. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.2.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boeve BF, Silber MH, Parisi JE, Dickson DW, Ferman TJ, Benarroch EE, Schmeichel AM, Smith GE, Petersen RC, Ahlskog JE, Matsumoto JY, Knopman DS, Schenck CH, Mahowald MW. Synucleinopathy pathology and REM sleep behavior disorder plus dementia or parkinsonism. Neurology. 2003;61:40–45. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000073619.94467.b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fulda S. Idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder as a long-term predictor of neurodegenerative disorders. EPMA J. 2011;2:451–458. doi: 10.1007/s13167-011-0096-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boeve BF. REM sleep behavior disorder: Updated review of the core features, the REM sleep behavior disorder-neurodegenerative disease association, evolving concepts, controversies, and future directions. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1184:15–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05115.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lu J, Sherman D, Devor M, Saper CB. A putative flip-flop switch for control of REM sleep. Nature. 2006;441:589–594. doi: 10.1038/nature04767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hickey MG, Demaerschalk BM, Caselli RJ, Parish JM, Wingerchuk DM. “Idiopathic” rapid-eye-movement (REM) sleep behavior disorder is associated with future development of neurodegenerative diseases. Neurologist. 2007;13:98–101. doi: 10.1097/01.nrl.0000257848.06462.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scherfler C, Frauscher B, Schocke M, Iranzo A, Gschliesser V, Seppi K, Santamaria J, Tolosa E, Hogl B, Poewe W. White and gray matter abnormalities in idiopathic rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder: A diffusion-tensor imaging and voxel-based morphometry study. Ann Neurol. 2011;69:400–407. doi: 10.1002/ana.22245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boeve BF, Silber MH, Saper CB, Ferman TJ, Dickson DW, Parisi JE, Benarroch EE, Ahlskog JE, Smith GE, Caselli RC, Tippman-Peikert M, Olson EJ, Lin SC, Young T, Wszolek Z, Schenck CH, Mahowald MW, Castillo PR, Del Tredici K, Braak H. Pathophysiology of REM sleep behaviour disorder and relevance to neurodegenerative disease. Brain. 2007;130:2770–2788. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boeve BF, Silber MH, Ferman TJ, Lin SC, Benarroch EE, Schmeichel AM, Ahlskog JE, Caselli RJ, Jacobson S, Sabbagh M, Adler C, Woodruff B, Beach TG, Iranzo A, Gelpi E, Santamaria J, Tolosa E, Singer C, Mash DC, Luca C, Arnulf I, Duyckaerts C, Schenck CH, Mahowald MW, Dauvilliers Y, Graff-Radford NR, Wszolek ZK, Parisi JE, Dugger B, Murray ME, Dickson DW. Clinicopathologic correlations in 172 cases of rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder with or without a coexisting neurologic disorder. Sleep Med. 2013;14:754–762. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2012.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murray ME, Ferman TJ, Boeve BF, Przybelski SA, Lesnick TG, Liesinger AM, Senjem ML, Gunter JL, Preboske GM, Lowe VJ, Vemuri P, Dugger BN, Knopman DS, Smith GE, Parisi JE, Silber MH, Graff-Radford NR, Petersen RC, Jack CR, Jr, Dickson DW, Kantarci K. MRI and pathology of REM sleep behavior disorder in dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurology. 2013;81:1681–1689. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000435299.57153.f0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watson NF, Viola-Saltzman M. Sleep and comorbid neurologic disorders. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2013;19:148–169. doi: 10.1212/01.CON.0000427208.13553.8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galasko D, Hansen LA, Katzman R, Wiederholt W, Masliah E, Terry R, Hill LR, Lessin P, Thal LJ. Clinical-neuropathological correlations in Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias. Arch Neurol. 1994;51:888–895. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1994.00540210060013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gomez-Isla T, Growdon WB, McNamara M, Newell K, Gomez-Tortosa E, Hedley-Whyte ET, Hyman BT. Clinicopathologic correlates in temporal cortex in dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurology. 1999;53:2003–2009. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.9.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, Bang W, Bennett DA. Mixed brain pathologies account for most dementia cases in community-dwelling older persons. Neurology. 2007;69:2197–2204. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000271090.28148.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferman TJ, Boeve BF, Smith GE, Lin SC, Silber MH, Pedraza O, Wszolek Z, Graff-Radford NR, Uitti R, Van Gerpen J, Pao W, Knopman D, Pankratz VS, Kantarci K, Boot B, Parisi JE, Dugger BN, Fujishiro H, Petersen RC, Dickson DW. Inclusion of RBD improves the diagnostic classification of dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurology. 2011;77:875–882. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31822c9148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadian EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: Report of the NINCDS-ADRDA work group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services task force on Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1984;34:6. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hughes AJ, Ben-Shlomo Y, Daniel SE, Lees AJ. What features improve the accuracy of clinical diagnosis in Parkinson’s disease: A clinicopathologic study. Neurology. 1992;42:1142–1146. doi: 10.1212/wnl.42.6.1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoehn MM, Yahr MD. Parkinsonism: Onset, progression and mortality. Neurology. 1967;17:427–442. doi: 10.1212/wnl.17.5.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders DSM-IV-TR. 4. American Psychiatric Association; Arlington, VA: 2000. (Text Revision) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Han C, Jo SA, Jo I, Kim E, Park MH, Kang Y. An adaptation of the Korean Mini-Mental State Examination (K-MMSE) in elderly Koreans: Demographic influence and population-based norms (the AGE study) Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2008;47:302–310. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morris JC. Clinical dementia rating: A reliable and valid diagnostic and staging measure for dementia of the Alzheimer type. Int Psychogeriatr. 1997;9(Suppl 1):173–176. doi: 10.1017/s1041610297004870. discussion 177–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee SA, Paek JH, Han SH, Ryu HU. The utility of a Korean version of the REM sleep behavior disorder screening questionnaire in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. J Neurol Sci. 2015;358:328–332. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2015.09.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Noguchi-Shinohara M, Tokuda T, Yoshita M, Kasai T, Ono K, Nakagawa M, El-Agnaf OM, Yamada M. CSF alpha-synuclein levels in dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res. 2009;1251:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.11.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Toledo JB, Korff A, Shaw LM, Trojanowski JQ, Zhang J. CSF alpha-synuclein improves diagnostic and prognostic performance of CSF tau and Abeta in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;126:683–697. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1148-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gagnon J, Petit D, Fantini M, Rompré S, Gauthier S, Panisset M, Robillard, Montplaisir J. REM sleep behavior disorder and REM sleep without atonia in probable Alzheimer disease. Sleep. 2006;29:1321–1325. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.10.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Postuma RB, Gagnon JF, Montplaisir J. Rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder as a biomarker for neurodegeneration: The past 10 years. Sleep Med. 2013;14:763–767. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schenck CH, Bundlie SR, Mahowald MW. Delayed emergence of a parkinsonian disorder in 38% of 29 older men initially diagnosed with idiopathic rapid eye movement sleep behaviour disorder. Neurology. 1996;46:388–393. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.2.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boissard R, Fort P, Gervasoni D, Barbagli B, Luppi PH. Localization of the GABAergic and non-GABAergic neurons projecting to the sublaterodorsal nucleus and potentially gating paradoxical sleep onset. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;18:1627–1639. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boissard R, Gervasoni D, Schmidt MH, Barbagli B, Fort P, Luppi PH. The rat ponto-medullary network responsible for paradoxical sleep onset and maintenance: A combined microinjection and functional neuroanatomical study. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;16:1959–1973. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garcia-Lorenzo D, Longo-Dos Santos C, Ewenczyk C, Leu-Semenescu S, Gallea C, Quattrocchi G, Pita Lobo P, Poupon C, Benali H, Arnulf I, Vidailhet M, Lehericy S. The coeruleus/subcoeruleus complex in rapid eye movement sleep behaviour disorders in Parkinson’s disease. Brain. 2013;136:2120–2129. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malloy P, Correia S, Stebbins G, Laidlaw DH. Neuroimaging of white matter in aging and dementia. Clin Neuropsychol. 2007;21:73–109. doi: 10.1080/13854040500263583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neikrug AB, Ancoli-Israel S. Diagnostic tools for REM sleep behavior disorder. Sleep Med Rev. 2012;16:415–429. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Consens FB, Chervin RD, Koeppe RA, Little R, Liu S, Junck L, Angell K, Heumann M, Gilman S. Validation of a polysomnographic score for REM sleep behavior disorder. Sleep. 2005;28:993–997. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.8.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Frauscher B, Gschliesser V, Brandauer E, Ulmer H, Peralta CM, Muller J, Poewe W, Hogl B. Video analysis of motor events in REM sleep behavior disorder. Mov Disord. 2007;22:1464–1470. doi: 10.1002/mds.21561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gagnon JF, Bedard MA, Fantini ML, Petit D, Panisset M, Rompre S, Carrier J, Montplaisir J. REM sleep behavior disorder and REM sleep without atonia in Parkinson’s disease. Neurology. 2002;59:585–589. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.4.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sixel-Doring F, Schweitzer M, Mollenhauer B, Trenkwalder C. Intraindividual variability of REM sleep behavior disorder in Parkinson’s disease: A comparative assessment using a new REM sleep behavior disorder severity scale (RBDSS) for clinical routine. J Clin Sleep Med. 2011;7:75–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang Y, Wang ZW, Yang YC, Wu HJ, Zhao HY, Zhao ZX. Validation of the rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder screening questionnaire in China. J Clin Neurosci. 2015;22:1420–1424. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2015.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mahlknecht P, Seppi K, Frauscher B, Kiechl S, Willeit J, Stockner H, Djamshidian A, Nocker M, Rastner V, Defrancesco M, Rungger G, Gasperi A, Poewe W, Hogl B. Probable RBD and association with neurodegenerative disease markers: A population-based study. Mov Disord. 2015;30:1417–1421. doi: 10.1002/mds.26350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haller S, Garibotto V, Kovari E, Bouras C, Xekardaki A, Rodriguez C, Lazarczyk MJ, Giannakopoulos P, Lovblad KO. Neuroimaging of dementia in 2013: What radiologists need to know. Eur Radiol. 2013;23:3393–3404. doi: 10.1007/s00330-013-2957-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]