The older the average person alive today becomes, the more instances of neurodegeneration are observed world-wide. Alzheimer's disease is the most common neurodegenerative disorder preferentially affecting older individuals with 26.6 million cases recorded in 2006. It is estimated that worldwide prevalence will rise to 100 million cases by 2050 1. There is currently no effective treatment nor preventative therapy for Alzheimer's disease, and no definitive diagnosis besides post-mortem pathology. Diagnosis is based on the presence of intracellular inclusions of hyperphosphorylated microtubule associated protein tau and extracellular plaques consisting of amyloid beta (Aβ) peptide 2. Aβ is a small peptide 40-42 aa in length, formed via amyloid precursor protein (APP) cleavage that results in Aβ release into the extracellular space. Aβ is normally observed circulating in the cerebrospinal fluid of mammals, and is produced mostly in the central nervous system 3. Although Aβ aggregates are the major pathological hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease, the mechanisms of Aβ induced neurotoxicity is not well understood, and even less is known about the physiological function of Aβ peptide. Absence of APP results in embryonic development defects due to irregular migration of cerebral cortex neurons 4. Recent work also indicates that Aβ peptide concentrations in the CNS modulate synaptic transmission and synaptic hyperactivity via direct binding to APP 5.

In addition to the pathological connection between Aβ deposition and Alzheimer’s, a genetic connection has been mapped as well. Multiple mutations in APP and its cleaving enzymes increase the risk of Alzheimer disease onset 6,7,8. Some mutations alter the cleavage of APP, resulting in a shifted ratio of Aβ1-42 to Aβ1-40, thus increasing the proportion of the more aggregation-prone species. Other mutations affect the aggregation propensity of the Aβ1-40/42 peptide itself 9. As with another aggregation-prone disease associated protein, α-synuclein in Parkinson’s disease, an increase in Aβ production results in its aggregation and the early onset of Alzheimer’s disease 10.

While most models of Aβ cellular pathology assume that toxicity stems from its aggregation propensity 11, there has been vigorous debate about whether the toxicity stems mostly from extracellular high-molecular weight amyloid plaques, or mostly from the low molecular weight oligomers 12,13,14. Aβ can be re-incorporated into the cytoplasm after extra-cellular cleavage, and much evidence has accumulated over the past several years that favors the small intracellular oligomers as the toxic aggregate species 15. Particularly convincing are seminal studies in simple models of disease: C. elegans and mice, demonstrating a link between aging, insulin signaling, and toxicity driven by low molecular weight oligomers of Aβ 16,17,18. Another study, modeling Alzheimer's disease in mice, showed that cognitive impairment precedes mature fibrillar deposits 19.

Due to the multifaceted and multifactorial nature of Alzheimer’s physiology, no single model can fully recapitulate disease. Mice are currently the model system that most closely resembles human beings while still being capable of exhibiting features of aging on a time-scale in line with the duration of a typical PhD or postdoc. Mice can also be scored for learning and memory defects, as well as motor neuron function. However, it is equally the case that a mouse that is artificially expressing extremely high amounts of Aβ in its brain will not accurately recapitulate the memory neuronal circuits of a 75-year-old human being. At the same time, mammalian models are sometimes less tractable and may offer less molecular and cellular detail of pathology and toxic events.

Simpler models of Aβ toxicity have been exploited with tremendous success towards greatly improving our understanding of the cellular pathology of molecular events associated with Alzheimer’s, as well as other neurodegenerative diseases. Of these, one of the most flexible, tractable, and versatile models has been the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae 20,21,22,23,24. One of the things that make yeast such an important model for studying aggregation toxicity is that aggregation-prone, disease-associated proteins that would normally kill any mammalian cell are usually only mildly toxic in yeast. This suggests that yeast have efficient mechanisms for avoiding the aggregate toxicity that many human cells, and especially neurons, eventually succumb to. These mechanisms can be investigated in yeast with the hope of eventually exploiting them to address human pathology.

Another enormous advantage of yeast is the ease with which they can be used for high-throughput and high-content screening of genetic components of disease-associated molecular processes, as well as small molecule modulators of toxicity. Using a variety of high-throughput screening approaches several groups have identified genetic modifiers of α-synuclein toxicity 21,25, ALS-associated pathology 26, as well as Alzherimer’s-associated aggregation 27. Similarly, a number of promising small molecular modifiers of Parkinson’s cellular pathology 20 have been discovered through yeast screening.

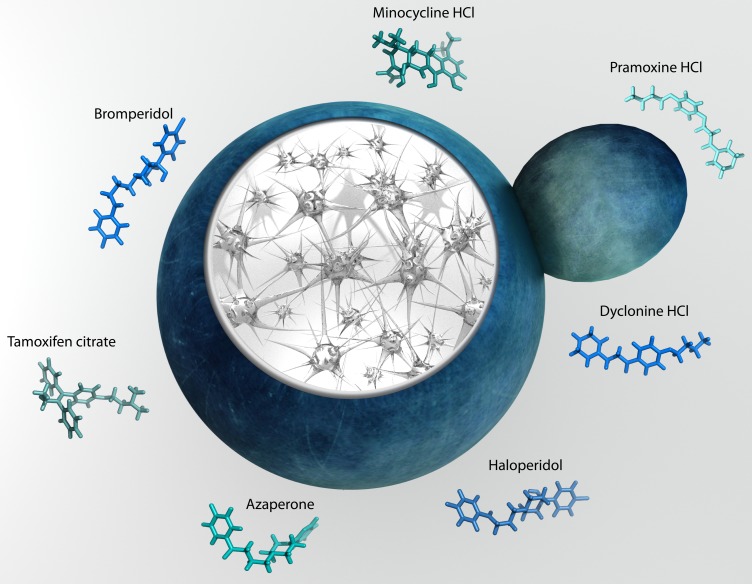

Recently, Park and colleagues working in Susan Liebman’s group discovered a number of small molecules capable of modulating Aβ aggregation in a yeast model 28. The group constructed an Aβ fused to a translation factor domain to assess the Aβ oligomerization with a simple growth assay 29. Park et al. screened 1200 FDA-approved drugs for the effect on Aβ oligomerization using a novel approach developed by the group earlier 28. The study uncovered 7 well-known compounds able to reduce oligomerization and rescue cellular toxicity in yeast (Fig. 1). These molecules were then shown to alleviate the toxic effects of Aβ aggregation in cultured mammalian cells, partially validating the yeast screen hits.

Figure 1. FIGURE 1: Yeast provide insight into molecular pathogenesis of Alzheimer disease and reveal modifiers of amyloid beta toxicity.

The molecules identified by the Liebman group show promise in that their molecular mechanism seems to involve modulating the small oligomers, thought to be the toxic species in the long chain of events leading to Aβ toxicity in the brain 28. All of the molecules identified have already been approved by the FDA for use in humans, significantly accelerating any potential drug-to-market timeline. The next step would be a direct test in an animal model of Alzheimer’s disease. In a promising precedent, a previous study describing novel targets for Parkinson’s disease in yeast has already proven to rescue neurons 21, illustrating the similarity and conservation in cellular response to amyloid aggregation, and the nearly unlimited utility of budding yeast to humanity30.

References

- 1.Brookmeyer R, Johnson E, Ziegler-Graham K, Arrighi HM. Forecasting the global burden of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2007;3(3):186–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2007.04.381S1552-5260(07)00475-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glenner GG, Wong CW, Quaranta V, Eanes ED. The amyloid deposits in Alzheimer's disease: their nature and pathogenesis. Appl Pathol. 1984;2(6):357–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Egensperger R, Weggen S, Ida N, Multhaup G, Schnabel R, Beyreuther K, Bayer TA. Reverse relationship between beta-amyloid precursor protein and beta-amyloid peptide plaques in Down's syndrome versus sporadic/familial Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neuropathol. 1999;97(2):113–118. doi: 10.1007/s004010050963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Young-Pearse TL, Bai J, Chang R, Zheng JB, LoTurco JJ, Selkoe DJ. A critical function for beta-amyloid precursor protein in neuronal migration revealed by In Utero RNA interference. J Neurosci. 2007;27(52):14459–14469. doi: 10.1523/Jneurosci.4701-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fogel H, Frere S, Segev O, Bharill S, Shapira I, Gazit N, O'Malley T, Slomowitz E, Berdichevsky Y, Walsh DM, Isacoff EY, Hirsch JA, Slutsky I. APP Homodimers Transduce an Amyloid-beta-Mediated Increase in Release Probability at Excitatory Synapses. Cell Rep. 2014;7(5):1560–1576. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haass C, Lemere CA, Capell A, Citron M, Seubert P, Schenk D, Lannfelt L, Selkoe DJ. The Swedish mutation causes early-onset Alzheimer's disease by beta-secretase cleavage within the secretory pathway. Nat Med. 1995;1(12):1291–1296. doi: 10.1038/nm1295-1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nilsberth C, Westlind-Danielsson A, Eckman CB, Condron MM, Axelman K, Forsell C, Stenh C, Luthman J, Teplow DB, Younkin SG, Naslund J, Lannfelt L. The 'Arctic' APP mutation (E693G) causes Alzheimer's disease by enhanced A beta protofibril formation. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4(9):887–893. doi: 10.1038/Nn0901-887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jankowsky JL, Fadale DJ, Anderson J, Xu GM, Gonzales V, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Lee MK, Younkin LH, Wagner SL, Younkin SG, Borchelt DR. Mutant presenilins specifically elevate the levels of the 42 residue beta-amyloid peptide in vivo: evidence for augmentation of a 42-specific gamma secretase. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13(2):159–170. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh019ddh019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okereke OI, Selkoe DJ, Grodstein F. Plasma beta-amyloid level, cognitive reserve, and cognitive decline. JAMA. 2011;305(16):1655–1656. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.524305/16/1655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rovelet-Lecrux A, Hannequin D, Raux G, Le Meur N, Laquerriere A, Vital A, Dumanchin C, Feuillette S, Brice A, Vercelletto M, Dubas F, Frebourg T, Campion D. APP locus duplication causes autosomal dominant early-onset Alzheimer disease with cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Nat Genet. 2006;38(1):24–26. doi: 10.1038/ng1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Brien RJ, Wong PC. Amyloid precursor protein processing and Alzheimer's disease. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2011;34(185-204) doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-061010-113613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nagele RG, D'Andrea MR, Anderson WJ, Wang HY. Intracellular accumulation of beta-amyloid(1-42) in neurons is facilitated by the alpha 7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor in Alzheimer's disease. Neuroscience. 2002;110(2):199–211. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4522(01)00460-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walsh DM, Klyubin I, Fadeeva JV, Cullen WK, Anwyl R, Wolfe MS, Rowan MJ, Selkoe DJ. Naturally secreted oligomers of amyloid beta protein potently inhibit hippocampal long-term potentiation in vivo. Nature. 2002;416(6880):535–539. doi: 10.1038/416535a416535a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cleary JP, Walsh DM, Hofmeister JJ, Shankar GM, Kuskowski MA, Selkoe DJ, Ashe KH. Natural oligomers of the amyloid-protein specifically disrupt cognitive function. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(1):79–84. doi: 10.1038/nn1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walsh DM, Tseng BP, Rydel RE, Podlisny MB, Selkoe DJ. The oligomerization of amyloid beta-protein begins intracellularly in cells derived from human brain. Biochemistry-Us. 2000;39(35):10831–10839. doi: 10.1021/Bi001048s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cohen E, Bieschke J, Perciavalle RM, Kelly JW, Dillin A. Opposing activities protect against age-onset proteotoxicity. Science. 2006;313(5793):1604–1610. doi: 10.1126/science.1124646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen E, Paulsson JF, Blinder P, Burstyn-Cohen T, Du DG, Estepa G, Adame A, Pham HM, Holzenberger M, Kelly JW, Masliah E, Dillin A. Reduced IGF-1 Signaling Delays Age-Associated Proteotoxicity in Mice. Cell. 2009;139(6):1157–1169. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.El-Ami T, Moll L, Marques FC, Volovik Y, Reuveni H, Cohen E. A novel inhibitor of the insulin/IGF signaling pathway protects from age-onset, neurodegeneration-linked proteotoxicity. Aging Cell. 2014;13(1):165–174. doi: 10.1111/acel.12171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mucke L, Selkoe DJ. Neurotoxicity of amyloid beta-protein: synaptic and network dysfunction. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2(7):a006338. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006338a006338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Su LHJ, Auluck PK, Outeiro TF, Yeger-Lotem E, Kritzer JA, Tardiff DF, Strathearn KE, Liu F, Cao SS, Hamamichi S, Hill KJ, Caldwell KA, Bell GW, Fraenkel E, Cooper AA, Caldwell GA, McCaffery JM, Rochet JC, Lindquist S. Compounds from an unbiased chemical screen reverse both ER-to-Golgi trafficking defects and mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson's disease models. Dis Model Mech. 2010;3(3-4):194–208. doi: 10.1242/dmm.004267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tardiff DF, Jui NT, Khurana V, Tambe MA, Thompson ML, Chung CY, Kamadurai HB, Kim HT, Lancaster AK, Caldwell KA, Caldwell GA, Rochet JC, Buchwald SL, Lindquist S. Yeast Reveal a "Druggable" Rsp5/Nedd4 Network that Ameliorates alpha-Synuclein Toxicity in Neurons. Science. 2013;342(6161):979–983. doi: 10.1126/science.1245321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tenreiro S, Reimao-Pinto MM, Antas P, Rino J, Wawrzycka D, Macedo D, Rosado-Ramos R, Amen T, Waiss M, Magalhaes F, Gomes A, Santos CN, Kaganovich D, Outeiro TF. Phosphorylation Modulates Clearance of Alpha-Synuclein Inclusions in a Yeast Model of Parkinson's Disease. Plos Genet. 2014;10(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Outeiro TF, Lindquist S. Yeast cells provide insight into alpha-synuclein biology and pathobiology. Science. 2003;302(5651):1772–1775. doi: 10.1126/science.1090439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Figley MD, Gitler AD. Yeast genetic screen reveals novel therapeutic strategy for ALS. Rare Dis. 2013;1:e24420. doi: 10.4161/rdis.244202013RAREDIS021R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chung CY, Khurana V, Auluck PK, Tardiff DF, Mazzulli JR, Soldner F, Baru V, Lou YL, Freyzon Y, Cho S, Mungenast AE, Muffat J, Mitalipova M, Pluth MD, Jui NT, Schule B, Lippard SJ, Tsai LH, Krainc D, Buchwald SL, Jaenisch R, Lindquist S. Identification and Rescue of alpha-Synuclein Toxicity in Parkinson Patient-Derived Neurons. Science. 2013;342(6161):983–987. doi: 10.1126/science.1245296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun ZH, Diaz Z, Fang XD, Hart MP, Chesi A, Shorter J, Gitler AD. Molecular Determinants and Genetic Modifiers of Aggregation and Toxicity for the ALS Disease Protein FUS/TLS. Plos Biol. 2011;9(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Treusch S, Hamamichi S, Goodman JL, Matlack KES, Chung CY, Baru V, Shulman JM, Parrado A, Bevis BJ, Valastyan JS, Han H, Lindhagen-Persson M, Reiman EM, Evans DA, Bennett DA, Olofsson A, DeJager PL, Tanzi RE, Caldwell KA, Caldwell GA, Lindquist S. Functional Links Between A beta Toxicity, Endocytic Trafficking, and Alzheimer's Disease Risk Factors in Yeast. Science. 2011;334(6060):1241–1245. doi: 10.1126/science.1213210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sei-Kyoung Park KR, Mariam Ba, Maria Valencik, Susan W Liebman. Inhibition of Aβ42 oligomerization in yeast by a PICALM ortholog and certain FDA approved drugs. Microbial Cell. 2016;3(2):53–64. doi: 10.15698/mic2016.02.476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bagriantsev S, Liebman S. Modulation of A beta(42) low-n oligomerization using a novel yeast reporter system. Bmc Biol. 2006;4:32. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-4-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaganovich D, Kopito R, Frydman J. Misfolded proteins partition between two distinct quality control compartments. Nature. 2008;454(7208):1088–U1036. doi: 10.1038/nature07195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]