Abstract

During aerobic respiration, cells produce energy through oxidative phosphorylation, which includes a specialized group of multi-subunit complexes in the inner mitochondrial membrane known as the electron transport chain. However, this canonical pathway is branched into single polypeptide alternative routes in some fungi, plants, protists and bacteria. They confer metabolic plasticity, allowing cells to adapt to different environmental conditions and stresses. Type II NAD(P)H dehydrogenases (also called alternative NAD(P)H dehydrogenases) are non-proton pumping enzymes that bypass complex I. Recent evidence points to the involvement of fungal alternative NAD(P)H dehydrogenases in the process of programmed cell death, in addition to their action as overflow systems upon oxidative stress. Consistent with this, alternative NAD(P)H dehydrogenases are phylogenetically related to cell death - promoting proteins of the apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF)-family.

Keywords: alternative NAD(P)H dehydrogenases, fungi, programmed cell death, ROS

INTRODUCTION

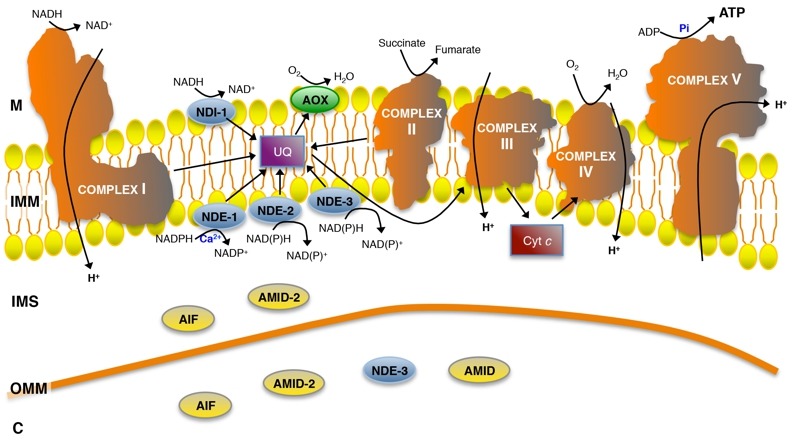

Mitochondria (from the Greek mitos and chondros, meaning "thread" and "granule", respectively) are the dynamos of the eukaryotic cell due to their major role in energy production under aerobic conditions. They are double membrane organelles: the protein-rich core of the organelle is known as the matrix, whereas the inner and outer mitochondrial membranes (IMM and OMM, respectively) delimitate the intermembrane space. The inner membrane forms a series of invaginations designated as cristae. Mitochondria take up pyruvate formed during the first stage of carbon metabolism (glycolysis) and fatty acids, and convert them into energy 1. The respiratory chain in the IMM is composed of the multi-subunit enzymatic complexes (complex I, II, III and IV), together with ubiquinone (coenzyme Q) and cytochrome c (Fig. 1). These complexes possess a number of protein-associated prosthetic groups - flavin mononucleotide (FMN), flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD), iron-sulfur clusters (FeS), iron and copper ions and heme - that transport electrons. Ubiquinone and cytochrome c transfer electrons between complexes. The electrochemical gradient that triggers the rotation of the ATP synthase (complex V), which leads to the formation of ATP from the phosphorylation of ADP 2,3, is generated by the proton-pumping activity of (i) complex I (NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase), which uses NADH as a source of electrons, transferring them to ubiquinone via FMN and a series of iron-sulfur clusters, (ii) complex III (ubiquinol cytochrome c reductase), which transfers electrons from the reduced ubiquinone or ubiquinol to cytochrome c, and (iii) complex IV (cytochrome c oxidase), which catalyses electron transfer to molecular oxygen and reduces it to water. Complex II (succinate dehydrogenase) transfers electrons from succinate to ubiquinone, providing an alternative electron entry point into the respiratory chain without proton pumping. Apart from the generation of energy, mitochondria are involved in several other cellular processes, like the biogenesis of iron-sulphur clusters, Ca2+ storage, intermediary metabolism, coenzyme biosynthesis and cell death 1.

Figure 1. FIGURE 1: Representation of the mitochondrial respiratory chain, alternative NAD(P)H dehydrogenases, alternative oxidase systems and AIF-family proteins of N. crassa.

M: mitochondrial matrix; IMM: mitochondrial inner membrane; IMS: intermembrane space; OMM: mitochondrial outer membrane; C: cytosol; UQ: ubiquinone; Cyt c: cytochrome c.

BRANCHED RESPIRATORY SYSTEMS IN FUNGI

In some fungi, plants, protists and bacteria, the electron transport chain is branched into single polypeptide alternative systems with no proton translocation activity that bypass the canonical pathway. The cyanide-resistant alternative oxidase (AOX) constitutes a well-established bypass of

complexes III and IV, whereas type II NAD(P)H dehydrogenases (or alternative NAD(P)H dehydrogenases) bypass complex I 4,5. Alternative NAD(P)H dehydrogenases are particularly important not only because they oxidize NAD(P)H and reduce quinones but also because they serve as entry points for electrons into the respiratory chain 6,7. Their importance is firmly demonstrated in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, where complex I is absent 8 and type II NAD(P)H dehydrogenases are the only existing NAD(P)H oxidases 9,10. These enzymes are flavoproteins resistant to classical complex I inhibitors, such as rotenone or piericidin A, and there is no selective and reliable drug to block them so far, although inhibition is feasible with diphenyleneiodonium 11,12,13. Alternative NAD(P)H dehydrogenases usually, but not always, contain FAD as the sole prosthetic group 4,5,7. Recently, an in silico approach identified putative alternative NAD(P)H dehydrogenases in a few metazoan organisms, but a functional verification is still missing 14.

In addition to complex I, our group characterized four alternative rotenone-insensitive NAD(P)H dehydrogenases in Neurospora crassa (Fig. 1 and Table 1) 6,7. They are associated with the inner mitochondrial membrane, but while one of them, NDI-1 15, is localized at the matrix side of the membrane, the other three, NDE-1 16,17, NDE-2 18 and NDE-3 19, are facing the intermembrane space. Interestingly, NDE-3 was also found in the cytosol 19.

Table 1.

Main features of N. crassa alternative NAD(P)H dehydrogenases.

a Ca2+ stimulates the oxidation of cytosolic NADH in a Δnde-1Δnde-2 double mutant, but not in the triple mutant Δnde-1Δnde-2Δndi-1, indicating that NDI-1 may be stimulated by Ca2+ 18. NA: not assessed.

| Protein | Topology | Substrate specificity | Ca2+ | pH | Reference(s) |

| NDE-1 | External | Cytosolic NADPH | Ca2+-dependent | Physiological pH | 16,17 |

| NDE-2 | External | Cytosolic NADH and NADPH | - | NADH throughout the pH range and NADPH at acidic pH | 18 |

| NDE-3 | External | Cytosolic NADH and NADPH | - | NA | 19 |

| NDI-1 | Internal | Matrix NADH | Ca2+-stimulated? a | NA | 15,18 |

Plants contain even more type II NAD(P)H dehydrogenases than fungi. Seven of these enzymes have been identified in Arabidopsis thaliana: three external (NDB1, NDB2 and NDB4), three internal (NDA1, NDA2 and NDC1) and one uncharacterized (NDB3) 20,21,22. Motifs in the N’-terminal portion of the proteins appear to determine mitochondrial import and their localization to either side of the inner membrane 23. Interestingly, dual targeting to mitochondria and chloroplasts or peroxisomes was claimed in some cases, although its functional relevance is unknown 24.

Alternative NAD(P)H dehydrogenases may be organized in supramolecular entities, similarly to the respiratory chain supercomplexes. There is evidence showing that in yeast these enzymes form a complex with a glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, two L-lactate-dehydrogenases, a few enzymes from the tricarboxylic acid cycle, two probable flavoproteins and an acetaldehyde dehydrogenase 25. In addition, the Yarrowia lipolytica alternative external NADH dehydrogenase and complex IV are associated, particularly in high energy-requiring, logarithmic-growth phase cells 26,27. Current literature suggests that the formation of supercomplexes, that include NAD(P)H dehydrogenases, might be related with electron channelling 25,27. In N. crassa, there is no evidence for the formation of supercomplexes containing alternative NAD(P)H dehydrogenases 28, but observations point to some kind of interaction between NDE-2 and complex I 18. N. crassa NDE-1 stands out because of its unique NADPH selectivity and regulation by pH and Ca2+ 17, the latter feature likely related to the presence of a conserved Ca2+-binding domain 16. In plants, the external NDB1 oxidizes NADPH in a Ca2+-dependent manner while NDB2 is a NADH dehydrogenase stimulated by Ca2+ 22,29.

The physiological role of alternative NAD(P)H dehydrogenases is still somehow controversial, although it is fairly well established that they confer metabolic plasticity allowing cells to adapt to different environmental and stress conditions. They may act as overflow systems keeping cytosolic and mitochondrial reducing equivalents (NADH, NADPH) at physiological levels, thus avoiding potential tricarboxylic cycle repression by elevated NADH levels and excessive levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) 4,5,7,30. Heterologous expression of Ndi1 from yeast was shown to reduce mammalian complex I-mediated ROS generation 31. In contrast, S. cerevisiae alternative NADH dehydrogenases have been proposed as potential sources of superoxide radicals by other studies 32,33,34.

In N. crassa, expression of alternative NAD(P)H dehydrogenases genes greatly depends on the growth phase 15,18,19,35. It is not possible to obtain viable double mutants between NDE-2 and complex I mutants that lack a functional enzyme, suggesting that NDE-2 and complex I interact in a yet unidentified pathway 18.

Humans do not possess alternative NAD(P)H dehydrogenases, but enzymes from other organisms have potential to be used in gene-based therapies. Heterologous expression of the yeast Ndi1 restores respiration in complex I-deficient human cells 36 and was also shown to be protective in in vivo models of Parkinson’s disease 37,38, Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy 39 and breast cancer 40.

Because mammals lack alternative NAD(P)H dehydrogenases, these enzymes are good candidate targets for human therapy in cases of fungal infection. The crystal structure of yeast Ndi1 has been recently solved and will allow a better understanding of the regulatory mechanisms of type II NAD(P)H dehydrogenases and likely lead to an evaluation of their potential as therapeutical agents or targets 41,42.

ALTERNATIVE NAD(P)H DEHYDROGENASES AS MEDIATORS OF PROGRAMMED CELL DEATH

Several reports point to a role of fungal alternative NAD(P)H dehydrogenases in cell death. In S. cerevisiae, overexpression of the internal Ndi1 (proposed as the yeast homologue of the human apoptosis-inducing factor-homologous mitochondrion-associated inducer of death or AMID), but not of the external Nde1, leads to ROS-mediated apoptosis-like cell death, particularly in glucose-rich media. The authors showed that the disruption of both of these NADH dehydrogenases results in lower ROS production and increased chronological life span accompanied by reduced fitness 34.

More recently, yeast Ndi1 was also shown to be involved in cell death induced by different stimuli like hydrogen peroxide, acetic acid and manganese ions, independently of its oxidoreductase activity 43. During the execution of manganese ion-induced cell death, a N’-terminal portion of Ndi1 is cleaved and the protein translocates to the cytoplasm. However, in sharp contrast, it was reported that overexpression of yeast Ndi1 in human cell lines prevents rotenone- and paraquat-induced cell death 44,45.

Thus, the specific role of alternative NAD(P)H dehydrogenases in the protection or enhancement of ROS production is still uncertain 27,31,32,45,46,47,48. Although speculative, it is possible that the discrepant findings observed in human and yeast cells overexpressing Ndi1 result from the fact that on the one hand, human cells do not possess these enzymes, and one the other hand, yeast cells harbor additional NAD(P)H dehydrogenases. In both cases, this suggests that alternative NAD(P)H dehydrogenases may interact with each other or respond to overexpression or downregulation of other members of the family. In fact, compensatory mechanisms of gene expression have been demonstrated in N. crassa strains lacking one or more NAD(P)H dehydrogenases (see below).

In N. crassa, a double mutant devoid of NDE-1 and NDE-2 displays lower ROS accumulation, increased catalase activity and resistance to paraquat 46. Particularly, NDE-2 appears to be engaged in mitochondrial ROS generation. In A. nidulans, the expression of genes encoding NAD(P)H dehydrogenases are induced upon exposure to different cell death stimuli, especially farnesol 49. Moreover, while the overexpression of NdiA augments the resistance to farnesol, the deletion of NdeA results in hypersensitivity to the drug. The latter is likely due to increased accumulation of ROS in the presence of farnesol 49. In N. crassa, disruption of nde-1 leads to increased susceptibility to staurosporine, associated with higher ROS accumulation and altered intracellular Ca2+ dynamics (Gonçalves AP, Cordeiro JM, Monteiro J, Lucchi C, Correia-de-Sá P, Videira A, unpublished data). In addition, a yeast NDE1 deletion strain is more resistant to artemisinin and dimeric naphthoquinones 50,51. Despite the aforementioned controversy around the role of NAD(P)H dehydrogenases during cell death, a current view is that these enzymes seem to be activated in different model organisms in conditions of highly reducing cellular environment, diverging electron transfer from the canonical respiratory chain pathway and thus avoiding system overflow and deleterious ROS production 27,47.

Notably, alternative NAD(P)H dehydrogenases are protein homologues of apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF)-family members, namely the well established cell death executioners AIF and AMID (Fig. 1). AIF-family members have been described as oxidoreductases 52,53, but disruption of AIF or AMID does not affect complex I activity, nor does the supramolecular organization of the respiratory chain in N. crassa 35. In this fungus, AIF was found both in mitochondrial and cytosolic extracts 35, while, for comparison, two AIFs localized in the mitochondria and in the cytoplasm, respectively, have been reported in Podospora anserina 54. In N. crassa, AMID was found exclusively in the cytosol whereas a third member of this family, AMID-2, was found both in the mitochondria and in the cytosol but was only observed when AMID was absent, suggesting overlapping functions 35. A genome-wide association study on a wild population of N. crassa showed a genetic interaction between amid-2 and czt-1, a transcription factor that controls cell death and drug resistance 55.

In N. crassa, analysis of gene expression profiles of these families of genes in simple or multiple deletion strains for alternative NAD(P)H dehydrogenases showed the occurrence of compensatory mechanisms 19,35,46. For instance, ndi-1 is upregulated in a ∆nde-1∆nde-2 and in a ∆nde-2 strain, amid and amid-2 are upregulated in a triple ∆ndi-1∆nde-1∆nde-2 mutant, nde-1 is upregulated in ∆nde-3 cells and nde-2 is upregulated in ∆ndi-1, ∆nde-1 and ∆nde-3 single mutants. The functional meaning of this compensation in gene expression is currently unknown, but there is evidence in yeast that mitochondrial dysfunction leads to an alteration in gene expression through retrograde signaling in order to reduce the impact of this dysfunction on cellular fitness 56. Interestingly, a phylogenetic analysis showed that N. crassa NDE-3 clusters with AIF-like proteins rather than with the other NAD(P)H dehydrogenases 35, further suggesting a close relationship between these proteins.

Accumulating evidence clearly relates alternative NAD(P)H dehydrogenases to intracellular cell death routes. However, further studies are needed to better understand the mechanisms underlying their involvement in the cellular responses to cell death stimuli.

Funding Statement

We thank the SPELL website for providing access to the microarray datasets and for providing the query-driven search engine to get ranked co-regulators as used in our study. We further thank the providers of free software development tools (Code::Blocks, Bloodshed, Microsoft) and webserver tools (Apache Software Foundation, The PHP Group) which we used in this study. We thank Christopher Stratil for helpful comments on the manuscript.

References

- 1.Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, Walter P. Garland Science, Taylor and Francis Group, New York City NY, USA. 2008. Molecular Biology of the Cell. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dudkina NV, Kouril R, Peters K, Braun HP, Boekema EJ. Structure and function of mitochondrial supercomplexes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1797(6-7):664–670. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lenaz G, Genova ML. Structure and organization of mitochondrial respiratory complexes: a new understanding of an old subject. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;12(8):961–1008. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Melo AM, Bandeiras TM, Teixeira M. New insights into type II NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductases. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2004;68(4):603–616. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.68.4.603-616.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rasmusson AG, Geisler DA, Moller IM. The multiplicity of dehydrogenases in the electron transport chain of plant mitochondria. Mitochondrion. 2008;8(1):47–60. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Videira A, Duarte M. On complex I and other NADH:ubiquinone reductases of Neurospora crassa mitochondria. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2001;33(3):197–203. doi: 10.1023/A:1010778802236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Videira A, Duarte M. From NADH to ubiquinone in Neurospora mitochondria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1555(1-3):187–191. doi: 10.1016/S0005-2728(02)00276-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buschges R, Bahrenberg G, Zimmermann M, Wolf K. NADH: ubiquinone oxidoreductase in obligate aerobic yeasts. Yeast. 1994;10(4):475–479. doi: 10.1002/yea.320100406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Vries S, Van Witzenburg R, Grivell LA, Marres CA. Primary structure and import pathway of the rotenone-insensitive NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase of mitochondria from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eur J Biochem. 1992;203(3):587–592. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb16587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luttik MA, Overkamp KM, Kotter P, de Vries S, van Dijken JP, Pronk JT. The Saccharomyces cerevisiae NDE1 and NDE2 genes encode separate mitochondrial NADH dehydrogenases catalyzing the oxidation of cytosolic NADH. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(38):24529–24534. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.38.24529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dong CK, Patel V, Yang JC, Dvorin JD, Duraisingh MT, Clardy J, Wirth DF. Type II NADH dehydrogenase of the respiratory chain of Plasmodium falciparum and its inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2009;19(3):972–975. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.11.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roberts TH, Fredlund KM, Moller IM. Direct evidence for the presence of two external NAD(P)H dehydrogenases coupled to the electron transport chain in plant mitochondria. FEBS Lett. 1995;373(3):307–309. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)01059-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agius SC, Bykova NV, Igamberdiev AU, Moller IM. The internal rotenone-insensitive NADPH dehydrogenase contributes to malate oxidation by potato tuber and pea leaf mitochondria. Physiol Plant. 1998;104(329-336):329–336. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3054.1998.1040306.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matus-Ortega MG, Salmeron-Santiago KG, Flores-Herrera O, Guerra-Sanchez G, Martinez F, Rendon JL, Pardo JP. The alternative NADH dehydrogenase is present in mitochondria of some animal taxa. Comp Biochem Physiol Part D Genomics Proteomics. 2011;6(3):256–263. doi: 10.1016/j.cbd.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duarte M, Peters M, Schulte U, Videira A. The internal alternative NADH dehydrogenase of Neurospora crassa mitochondria. Biochem J. 2003;371(Pt 3):1005–1011. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Melo AM, Duarte M, Videira A. Primary structure and characterisation of a 64 kDa NADH dehydrogenase from the inner membrane of Neurospora crassa mitochondria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1412(3):282–287. doi: 10.1016/S0005-2728(99)00072-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Melo AM, Duarte M, Moller IM, Prokisch H, Dolan PL, Pinto L, Nelson MA, Videira A. The external calcium-dependent NADPH dehydrogenase from Neurospora crassa mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(6):3947–3951. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008199200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carneiro P, Duarte M, Videira A. The main external alternative NAD(P)H dehydrogenase of Neurospora crassa mitochondria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1608(1):45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carneiro P, Duarte M, Videira A. The external alternative NAD(P)H dehydrogenase NDE3 is localized both in the mitochondria and in the cytoplasm of Neurospora crassa. J Mol Biol. 2007;368(4):1114–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.02.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elhafez D, Murcha MW, Clifton R, Soole KL, Day DA, Whelan J. Characterization of mitochondrial alternative NAD(P)H dehydrogenases in Arabidopsis: intraorganelle location and expression. Plant Cell Physiol. 2006;47(1):43–54. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pci221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Michalecka AM, Svensson AS, Johansson FI, Agius SC, Johanson U, Brennicke A, Binder S, Rasmusson AG. Arabidopsis genes encoding mitochondrial type II NAD(P)H dehydrogenases have different evolutionary origin and show distinct responses to light. Plant Physiol. 2003;133(2):642–652. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.024208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geisler DA, Broselid C, Hederstedt L, Rasmusson AG. Ca2+-binding and Ca2+-independent respiratory NADH and NADPH dehydrogenases of Arabidopsis thaliana. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(39):28455–28464. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704674200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rasmusson AG, Svensson AS, Knoop V, Grohmann L, Brennicke A. Homologues of yeast and bacterial rotenone-insensitive NADH dehydrogenases in higher eukaryotes: two enzymes are present in potato mitochondria. Plant J. 1999;20(1):79–87. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1999.00576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carrie C, Murcha MW, Kuehn K, Duncan O, Barthet M, Smith PM, Eubel H, Meyer E, Day DA, Millar AH, Whelan J. Type II NAD(P)H dehydrogenases are targeted to mitochondria and chloroplasts or peroxisomes in Arabidopsis thaliana. FEBS Lett. 2008;582(20):3073–3079. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.07.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grandier-Vazeille X, Bathany K, Chaignepain S, Camougrand N, Manon S, Schmitter JM. Yeast mitochondrial dehydrogenases are associated in a supramolecular complex. Biochemistry. 2001;40(33):9758–9769. doi: 10.1021/bi010277r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guerrero-Castillo S, Vazquez-Acevedo M, Gonzalez-Halphen D, Uribe-Carvajal S. In Yarrowia lipolytica mitochondria, the alternative NADH dehydrogenase interacts specifically with the cytochrome complexes of the classic respiratory pathway. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1787(2):75–85. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guerrero-Castillo S, Cabrera-Orefice A, Vazquez-Acevedo M, Gonzalez-Halphen D, Uribe-Carvajal S. During the stationary growth phase, Yarrowia lipolytica prevents the overproduction of reactive oxygen species by activating an uncoupled mitochondrial respiratory pathway. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1817(2):353–362. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marques I, Dencher NA, Videira A, Krause F. Supramolecular organization of the respiratory chain in Neurospora crassa mitochondria. Eukaryot Cell. 2007;6(12):2391–2405. doi: 10.1128/EC.00149-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Michalecka AM, Agius SC, Moller IM, Rasmusson AG. Identification of a mitochondrial external NADPH dehydrogenase by overexpression in transgenic Nicotiana sylvestris. Plant J. 2004;37(3):415–425. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rasmusson AG, Wallstrom SV. Involvement of mitochondria in the control of plant cell NAD(P)H reduction levels. Biochem Soc Trans. 2010;38(2):661–666. doi: 10.1042/BST0380661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seo BB, Marella M, Yagi T, Matsuno-Yagi A. The single subunit NADH dehydrogenase reduces generation of reactive oxygen species from complex I. FEBS Lett. 2006;580(26):6105–6108. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fang J, Beattie DS. External alternative NADH dehydrogenase of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: a potential source of superoxide. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;34(4):478–488. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(02)01328-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davidson JF, Schiestl RH. Mitochondrial respiratory electron carriers are involved in oxidative stress during heat stress in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21(24):8483–8489. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.24.8483-8489.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li W, Sun L, Liang Q, Wang J, Mo W, Zhou B. Yeast AMID homologue Ndi1p displays respiration-restricted apoptotic activity and is involved in chronological aging. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17(4):1802–1811. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-04-0333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carneiro P, Duarte M, Videira A. Characterization of apoptosis-related oxidoreductases from Neurospora crassa. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e34270. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seo BB, Kitajima-Ihara T, Chan EK, Scheffler IE, Matsuno-Yagi A, Yagi T. Molecular remedy of complex I defects: rotenone-insensitive internal NADH-quinone oxidoreductase of Saccharomyces cerevisiae mitochondria restores the NADH oxidase activity of complex I-deficient mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(16):9167–9171. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seo BB, Nakamaru-Ogiso E, Flotte TR, Matsuno-Yagi A, Yagi T. In vivo complementation of complex I by the yeast Ndi1 enzyme. Possible application for treatment of Parkinson disease. . J Biol Chem. 2006;281(20):14250–14255. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600922200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marella M, Seo BB, Nakamaru-Ogiso E, Greenamyre JT, Matsuno-Yagi A, Yagi T. Protection by the NDI1 gene against neurodegeneration in a rotenone rat model of Parkinson's disease. PLoS One. 2008;3(1):e1433. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marella M, Seo BB, Thomas BB, Matsuno-Yagi A, Yagi T. Successful amelioration of mitochondrial optic neuropathy using the yeast NDI1 gene in a rat animal model. PLoS One. 2010;5(7):e11472. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Santidrian AF, Matsuno-Yagi A, Ritland M, Seo BB, LeBoeuf SE, Gay LJ, Yagi T, Felding-Habermann B. Mitochondrial complex I activity and NAD+/NADH balance regulate breast cancer progression. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(3):1068–1081. doi: 10.1172/JCI64264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Feng Y, Li W, Li J, Wang J, Ge J, Xu D, Liu Y, Wu K, Zeng Q, Wu JW, Tian C, Zhou B, Yang M. Structural insight into the type-II mitochondrial NADH dehydrogenases. Nature. 2012;491(7424):478–482. doi: 10.1038/nature11541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Iwata M, Lee Y, Yamashita T, Yagi T, Iwata S, Cameron AD, Maher MJ. The structure of the yeast NADH dehydrogenase (Ndi1) reveals overlapping binding sites for water- and lipid-soluble substrates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(38):15247–15252. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1210059109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cui Y, Zhao S, Wu Z, Dai P, Zhou B. Mitochondrial release of the NADH dehydrogenase Ndi1 induces apoptosis in yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 2012;23(22):4373–4382. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E12-04-0281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marella M, Seo BB, Matsuno-Yagi A, Yagi T. Mechanism of cell death caused by complex I defects in a rat dopaminergic cell line. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(33):24146–24156. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701819200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Park JS, Li YF, Bai Y. Yeast NDI1 improves oxidative phosphorylation capacity and increases protection against oxidative stress and cell death in cells carrying a Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy mutation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1772(5):533–542. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carneiro P, Duarte M, Videira A. Disruption of alternative NAD(P)H dehydrogenases leads to decreased mitochondrial ROS in Neurospora crassa. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;52(2):402–409. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.10.492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Voulgaris I, O'Donnell A, Harvey LM, McNeil B. Inactivating alternative NADH dehydrogenases: enhancing fungal bioprocesses by improving growth and biomass yield? Sci Rep. 2012;2(322) doi: 10.1038/srep00322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.O'Donnell A, Harvey LM, McNeil B. The roles of the alternative NADH dehydrogenases during oxidative stress in cultures of the filamentous fungus Aspergillus niger. Fungal Biol. 2011;115(4-5):359–369. doi: 10.1016/j.funbio.2011.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dinamarco TM, Pimentel Bde C, Savoldi M, Malavazi I, Soriani FM, Uyemura SA, Ludovico P, Goldman MH, Goldman GH. The roles played by Aspergillus nidulans apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF)-like mitochondrial oxidoreductase (AifA) and NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductases (NdeA-B and NdiA) in farnesol resistance. Fungal Genet Biol. 2010;47(12):1055–1069. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li W, Mo W, Shen D, Sun L, Wang J, Lu S, Gitschier JM, Zhou B. Yeast model uncovers dual roles of mitochondria in action of artemisinin. PLoS Genet. 2005;1(3):e36. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Emadi A, Ross AE, Cowan KM, Fortenberry YM, Vuica-Ross M. A chemical genetic screen for modulators of asymmetrical 2,2'-dimeric naphthoquinones cytotoxicity in yeast. PLoS One. 2010;5(5):e10846. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miramar MD, Costantini P, Ravagnan L, Saraiva LM, Haouzi D, Brothers G, Penninger JM, Peleato ML, Kroemer G, Susin SA. NADH oxidase activity of mitochondrial apoptosis-inducing factor. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(19):16391–16398. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010498200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Marshall KR, Gong M, Wodke L, Lamb JH, Jones DJ, Farmer PB, Scrutton NS, Munro AW. The human apoptosis-inducing protein AMID is an oxidoreductase with a modified flavin cofactor and DNA binding activity. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(35):30735–30740. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414018200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brust D, Hamann A, Osiewacz HD. Deletion of PaAif2 and PaAmid2, two genes encoding mitochondrial AIF-like oxidoreductases of Podospora anserina, leads to increased stress tolerance and lifespan extension. Curr Genet. 2010;56(3):225–235. doi: 10.1007/s00294-010-0295-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Goncalves AP, Hall C, Kowbel DJ, Glass NL, Videira A. CZT-1 Is a Novel Transcription Factor Controlling Cell Death and Natural Drug Resistance in Neurospora crassa. G3 (Bethesda) 2014;4(6):1091–1102. doi: 10.1534/g3.114.011312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liu Z, Butow RA. A transcriptional switch in the expression of yeast tricarboxylic acid cycle genes in response to a reduction or loss of respiratory function. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19(10):6720–6728. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.10.6720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]