Abstract

One of the fundamental challenges to implementing successful prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) programs in Nigeria is the uptake of PMTCT services at health facilities. Several issues usually discourage many pregnant women from receiving antenatal care services at designated health facilities within their communities. The CRS Nigeria PMTCT Project funded by the Global Fund in its Round 9 Phase 1 in Nigeria, sought to increase demand for HIV counseling and testing services for pregnant women at 25 supported primary health centers (PHCs) in Kaduna State, North-West Nigeria by integrating traditional birth attendants (TBAs) across the communities where the PHCs were located into the project. Community dialogues were held with the TBAs, community leaders and women groups. These dialogues focused on modes of mother to child transmission of HIV and the need for TBAs to refer their clients to PHCs for testing. Subsequently, data on number of pregnant women who were counseled, tested and received results was collected on a monthly basis from the 25 facilities using the national HIV/AIDS tools. Prior to this integration, the average number of pregnant women that were counseled, tested and received results was 200 pregnant women across all the 25 health facilities monthly. After the integration of TBAs into the program, the number of pregnant women that were counseled, tested and received results kept increasing month after month up to an average of 1500 pregnant women per month across the 25 health facilities. TBAs can thus play a key role in improving service uptake and utilization for pregnant women at primary health centers in the community – especially in the context of HIV/AIDS. They thus need to be integrated, rather than alienated, from primary healthcare service delivery.

Key words: HIV/AIDS, prevention of mother-to-child transmission, traditional birth attendants, community mobilization

Introduction

Nigeria accounted for a third of new HIV infections among children in the UNAIDS 21 priority countries in Sub-Saharan Africa in 2012, with a 30% mother-to-child transmission rate of HIV.1 Despite efforts by the government and development partners to significantly scale up the provision of prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) services across most healthcare facilities (primary, secondary, and tertiary); commensurate improvement in uptake of services has not been observed. The various national challenges to increasing the uptake of antenatal care (ANC) and PMTCT services are quite common in Kaduna State in the North-West of the country. A study of previous HIV/AIDS treatment interventions including PMTCT in the state showed that less than 40% of pregnant women infected with HIV were enrolled in treatment. The study further indicated that some of the disclosed reasons why uptake of services was very poor included lack of awareness about services at health facilities, long waiting times, different hospital appointments for different services, cost of transportation to health facility, and availability of alternative medicine practitioners as well as traditional birth attendants (TBAs) in their immediate communities.2

The national PMTCT coverage (at the time of intervention) was 16.9% of all pregnant women accessing HIV testing and ccounselling and it fell far below the national targets of 60% by 2012.3 Also, only 32% of pregnant women had been counseled and tested and received results during ANC in Kaduna, while awareness of PMTCT was only 59.25% among women.2 Also, previous interventions had been mainly facility-based and had thus failed to incorporate the communities via social mobilization. Creating awareness on the issues surrounding PMTCT at the grassroots level help to create demand for uptake of PMTCT services at the health facilities.4

Catholic Relief Services (CRS) Nigeria was a sub-recipient to the National Agency for the Control of AIDS under the Global Fund Round 1 Phase HIV grants in Nigeria. The CRS-managed component was focused on delivering PMTCT services in PHCs. The overall goal of this PMTCT project was to scale up gender sensitive HIV prevention, treatment and care services to HIV positive pregnant women thereby preventing their babies from getting infected with HIV. Prior to project implementation, it was observed from a survey carried out to map out support structures as well as challenges and threats to the project that about 75% of reproductive-age female respondents preferred to deliver their babies with a TBA than at a health facility (Catholic Relief Services Nigeria 2012, unpublished report). This is consistent with other studies,4,5 as well as with the National Demographic and Health Survey (2013) which showed that 67.5% of births are outside health facilities.6 In the light of these findings, it became imperative to engage with the TBAs in the project communities in order for the project to reach the target beneficiaries and achieve project outcomes. This report documents the lessons learned from integrating Traditional Birth Attendants in this project in order to enhance demand creation for PMTCT services at 25 local primary health facilities in Kaduna State between August and December 2012.

Materials and Methods

TBAs in our context are unskilled birth attendants in the community who assist mothers during childbirth and who initially acquired their skills by delivering babies themselves or by working with older TBAs.7 These TBAs are usually females especially in the Northern part of Nigeria, with only a small percentage being males. Mapping of TBAs was done in all the target communities in collaboration with the health workers in the PHCs and community leaders. The mapping revealed that some TBAs were preferred to others and thus had a larger clientele.

In order to have the number of TBAs that the project could effectively engage and monitor, four TBAs from each of the communities were invited for the initial meeting, making for a total of 100 across the 25 communities. The criteria for selecting these four was the average volume of new clients they had per month; with a minimum of 50 clients per month as the cut-off. During the initial community dialogues, stakeholders such as community leaders, local council officials, women groups and men who had been trained as peer educators were invited in order to ensure their buy-in. The challenge of HIV infection and the burden of mother-to-child transmission were carefully explained using local translators in the Hausa language. At the end, community leaders across the 25 communities gave approvals for the engagement to go ahead.

The TBAs in each community were subsequently invited for separate sessions where they were introduced to the project; the concepts of HIV and Mother-to-Child-Transmission of HIV, the modes of transmission the roles they would have to play in PMTCT – again using local translators in Hausa. This made it easy for all the TBAs to understand the risks involved in taking deliveries from women whose HIV status was not known. Hence, it was unanimously agreed by all of the TBAs that they would send their clients to the PHCs for HIV counseling and testing, while supporting those tested positive to remain clients of the PHC to receive ARV prophylaxis.

The very important issues of confidentiality, stigma and discrimination were discussed with the TBAs, and linkages between them and the PHC staff were also discussed in this regard in order to ensure proper management of client information. The TBAs were subsequently provided with simple data forms with which they were to refer their clients to the health centres. In the case of the illiterate TBAs, educated children or neighbours of each one were identified to assist with filling the forms. These forms were then used for tracking the number of women referred by the TBAs. Data on the referred pregnant women was documented at the health facility in the client intake registers, antenatal care (ANC) register and other national data collection tools. Other adjunct strategies employed to achieve the overall goal of the intervention included: i) advocacy to Kaduna State Ministry of Health and the 5 local councils where the 25 PHCs were located to provide adequate health personnel at the facilities and retention of trained health personnel; ii) training of Primary Healthcare facility personnel on Integrated Management of Adolescent and Childhood Illnesses and Integrated Management of Pregnancy and Child birth (IMAI/IMPAC); iii) support to male peer educators to conduct male involvement outreach activities to encourage participation and uptake of PMTCT services in the communities.

Results

The results were obtained from data collected on the key indicator in the ANC registers i.e. number of pregnant women counseled, tested and obtained results. This data was triangulated with the figures in client intake registers to safeguard data accuracy and quality. The data across all the 25 primary health facilities was collated month by month and aggregated together for cumulative monthly averages. Since only 25 health facilities were participating in this phase of the project, the aggregated data from all the facilities was used (instead of using a sample size) in the data analysis.

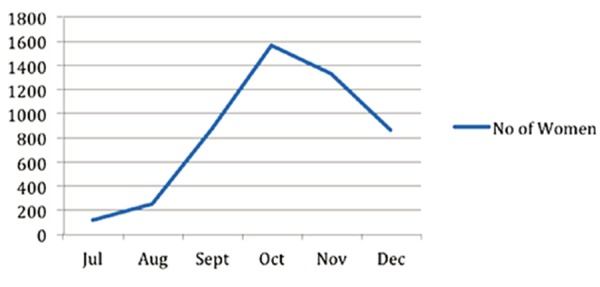

The results showed a significant increase in the number of pregnant who accessed counseling and testing services at the PHCs. Prior to the integration of TBAs in September 2012, the total number of pregnant women counseled and tested across the 25 facilities was around 200 per month. After the involvement of TBAs, the numbers increased to as much as 1500 monthly by October 2012. The analysis of data collected during that period (Figure 1) showed that the increase was as a result of the pregnant women referred by the TBAs during that period. The number of pregnant women counseled and tested at the health facilities kept increasing steadily month by month until after the third month, when other factors resulted in a decline.

Figure 1.

Total number of pregnant women counseled, tested and received results across the 25 primary health centers in Kaduna State (Nigeria) between July and December 2012.

Discussion

Although the period of engagement of TBAs was relatively short (the project was to end in December 2012), the data collected and analyzed during this time clearly indicated that the involvement of TBAs in the program improved both project outputs and outcomes significantly. More pregnant women were tested, more positive women were identified and placed on prophylaxis, and this in turn helped to reduce the transmission of HIV from these mothers to their unborn children. The decline after October 2012 was as a result of shortage of HIV rapid test kits at the PHCs. Most of the health facilities ran short of rapid test kits during this period, and the Supply Chain mechanisms within the state were also stocked out. Several women who had come out to be tested between November and December 2012 were turned back for this reason. Apart from the mother-to-child transmission risk of these missed opportunities, other untoward consequences of this stock-out were recorded in the community. For instance, it became more difficult to convince women to utilize the services at the PHCs because their confidence in the PHCs that was being restored was eroded in a short time.

There are controversies surrounding the involvement of TBAs in the health system.8,9 However, our engagement and integration of TBAs was primarily as a result of the situation on ground in the communities where we worked. It proved to be a good strategy to improve project outcomes, with the TBAs improving demand creation within the community to strengthen HIV/AIDS referral services to health facilities. This improved significantly the uptake of services provided by the government at the 25 health facilities. It is pertinent to remember that there is a gross inadequacy of skilled health workers especially in rural areas across Nigeria,10 and though various measures are being taken to address this,11 it is imperative to find ways of ameliorating the dismal maternal and child morbidity and mortality statistics until these measures yield fruit. Engaging TBAs in our experience is just such an ameliorating factor.

One major challenge in involving TBAs in this project was the pre-existing rivalries between them and the orthodox health workers at the communities.12 To ensure that TBAs worked seamlessly with facility health workers, we ensured that there was open dialogue between both groups in the course of the advocacy and engagement process. Meetings were held separately with the health workers prior to this dialogue to make them understand that the burden of MTCT required unorthodox approaches such as non-judgmental TBA involvement. Meetings were also held with the TBAs as previously discussed, and community leaders were equally sensitized on the MTCT problem and the need for TBAs and facility health workers to work together for the good of the community. All of these interactions made the integration of TBAs successful because everybody had a common understanding of the problem.

Conclusions

This intervention showed that participatory approaches involving non-orthodox actors can be very effective in tackling health issues – especially in the context of HIV/AIDS and PMTCT. Although TBAs are not recognized as part of the formal healthcare system; this experience showed that they could be very useful in mitigating various issues associated with poor maternal and child health as well as PMTCT. It is imperative for policy makers to acknowledge the importance of TBAs in community mobilization to enhance the success of PMTCT and other maternal and child health programs. Such an important group of people in our local communities should not be alienated from the process of seeking solutions to issues that affect the general community or public, such as HIV/AIDS.

This project also showed that when implementing health projects in local communities, approaches involving all community stakeholders are the most successful. The disease burdens should be identified objectively and the issues communicated clearly without disaffection to enable all interested groups involved to understand the problems and possibly contribute in proffering solutions. Consequently, with everybody involved on the same page, the actions taken to address the challenges are more likely to succeed because everybody owns the process.

Acknowledgments

The authors would thank the Global Fund and the grant Principal Recipient; the National Agency for the Control of AIDS (NACA) for funding the Round 9 Phase 1 PMTCT project from where this article emanated. The contents of this paper are purely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Catholic Relief Services, the National Agency for the Control of AIDS or the Global Fund.

References

- 1.UNAIDS. 2013 progress report on the global plan towards the elimination of new HIV infections among children by 2015 and keeping their mothers alive. 2013. Available from: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/20130625_progress_global_pla n_en_0.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oyeledun B, Oronsanye F, Oyeleke T, et al. Increasing retention in care of HIV positive women in PMTCT services through continuous quality improvement. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2014;67:S125-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Agency for Control of AIDS. Federal Republic of Nigeria - Global AIDS response: country progress report. 2014. Available frm: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/country/documents/NGA_narrative_report_2014.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 4.Isichei CO, Ammann AJ. The role of trained birth attendants in delivering PMTCT services. Am J Health Res 2015;3: 232-8. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fapohunda BM, Orobaton NG. When women deliver with no one present in Nigeria: who, what, where and so what? PLoS One. 2013,8:e69569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Population Commission (Nigeria) ICF Macro. Nigeria demographic and health survey 2008. Abuja: National Population Commission, ICF Macro; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 7.AMREF. AMREF position on the role and services of traditional birth attendants. Available from: http://amref.org/amref/en/info-hub/amrefs-position-on-the-role-and-services-of-traditional-birthattendants-/. Accessed on: December 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ana J. Are traditional birth attendants good for improving maternal and perinatal health? Yes. BMJ 2011;342:d3310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harrison KA. Are traditional birth attendants good for improving maternal and perinatal health? No. BMJ 2011;342:d3308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.USAID. A situation assessment of human resources the public health sector in Nigeria. 2006. Available from: http://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/Pnadh422.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abimbola S, Okoli U, Olubajo O, et al. The midwives service scheme in Nigeria. PLoS Med 2012;9:e1001211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inegbenebor U. Bridging the gap between concept and reality in the Nigeria midwives service scheme. S Am J Publ Health 2014;2:126-34. [Google Scholar]