The structure of ligand-free and DNA-unbound AmtR, a TetR-type global nitrogen regulator from C. glutamicum, was solved at 2.1 Å resolution in space group P21212 with six molecules in the asymmetric unit. A structure comparison with the previously solved structure of AmtR in a trigonal crystal system suggests a 6:6 stoichiometric association of three AmtR dimers with two trimeric GlnK complexes that prevents AmtR from binding to DNA and induces gene transcription.

Keywords: nitrogen regulation, Corynebacterium glutamicum, transcription regulator effector complex, AmtR adenylylated GlnK complex stoichiometry, crystal-packing comparison

Abstract

AmtR belongs to the TetR family of transcription regulators and is a global nitrogen regulator that is induced under nitrogen-starvation conditions in Corynebacterium glutamicum. AmtR regulates the expression of transporters and enzymes for the assimilation of ammonium and alternative nitrogen sources, for example urea, amino acids etc. The recognition of operator DNA by homodimeric AmtR is not regulated by small-molecule effectors as in other TetR-family members but by a trimeric adenylylated PII-type signal transduction protein named GlnK. The crystal structure of ligand-free AmtR (AmtRorth) has been solved at a resolution of 2.1 Å in space group P21212. Comparison of its quaternary assembly with the previously solved native AmtR structure (PDB entry 5dy1) in a trigonal crystal system (AmtRtri) not only shows how a solvent-content reduction triggers a space-group switch but also suggests a model for how dimeric AmtR might stoichiometrically interact with trimeric adenylylated GlnK.

1. Introduction

Prokaryotes have developed elaborate mechanisms to guarantee an optimal nitrogen supply during situations of nitrogen limitation. Nitrogen control in Corynebacterium glutamicum, a Gram-positive soil bacterium used for the industrial production of amino acids, is known to be regulated by the tetracycline repressor-type (TetR-type) regulator AmtR, which blocks the transcription of various genes during growth in nitrogen-rich medium (Amon et al., 2010 ▸; Jakoby et al., 1999 ▸).

In contrast to almost all other TetR-type regulators, which interact and are regulated by low-molecular-weight molecules such as tetracycline (Yu et al., 2010 ▸), binding of AmtR to promoter sequences is controlled through the formation of a protein complex, i.e. AmtR is released from its target DNA upon interaction with the trimeric PII-family signal transduction protein GlnK (Forchhammer, 2008 ▸; Strösser et al., 2004 ▸). However, for this protein–protein interaction to occur, it is essential that GlnK is adenylylated at tyrosine residue 51, which is located within the so-called T-loop of GlnK (Strösser et al., 2004 ▸).

With respect to the biological function of AmtR, the stoichiometry anticipated for the GlnK–AmtR interaction remains puzzling. Within the vast majority of TetR-family members, low-molecular-weight effectors bind to the dimeric repressors with a 2:2 stoichiometry (Sevvana et al., 2012 ▸; Yu et al., 2010 ▸). However, the occurrence of GlnK as a trimeric protein renders the formation of a 2:2 Glnk–AmtR complex unlikely. Some structural information is available for complexes formed between GlnK and other proteins. These complexes always display point-group symmetries involving threefold and twofold axes only, e.g. trimeric GlnK in complex with trimeric ammonium transporter AmtB (Conroy et al., 2007 ▸; Maier et al., 2011 ▸) or with the hexameric key enzyme for arginine biosynthesis, NAGK (Llácer et al., 2007 ▸).

In a previous report from our group, the crystallization of AmtR, data collection from native and selenomethionine-derivatized crystals as well as the phasing of these crystals belonging to space group P21212 using the Se-SAD method was reported (Hasselt et al., 2009 ▸). Here, the structure of AmtR that was obtained after model building using the above-obtained phases and following refinement against a newly collected native data set that extends to 2.1 Å resolution is described. The structure of AmtR is compared with that of a recently solved AmtR structure in a different space group (PDB entry 5dy1; AmtRtri; Palanca & Rubio, 2016 ▸). The analysis shows that these structures share several crystal-packing characteristics and suggests the formation of a 6:6 stoichiometric (AmtR2)3–(GlnK3)2 complex that precludes DNA binding of AmtR.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Macromolecule production

The production procedure has been slightly modified with respect to a previous report (Hasselt et al., 2009 ▸). 300 ml LB medium containing 2% glucose was inoculated with Escherichia coli BL21 cells freshly transformed with pMalc2amtR plasmid (containing AmtR with an MBP tag) and incubated overnight at 37°C (Table 1 ▸). This bacterial culture was used to inoculate 5 l fresh LB medium containing 2% glucose at an OD600 of 0.1, grown to an OD600 of 0.5 and then induced with 0.3 mM IPTG. After 4 h, the cells were harvested via centrifugation (3000g, 10 min, 4°C) and the pellet was resuspended in 60 ml purification buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4, 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA). The solution was sonicated three times for 30 s (energy 70%, Bandelin Sonoplus UW2070, Berlin), and the suspension was centrifuged for 60 min at 100 000g at 4°C. The supernatant was loaded onto a 5 ml MBP-Trap column (GE Healthcare, Munich) and washed with ten column volumes of purification buffer. The column was then incubated overnight with 30 µl 1 mg ml−1 factor Xa dissolved in 4 ml purification buffer. AmtR with no MBP tag was eluted with purification buffer. The uncleaved protein and the cleaved tag were eluted with 20 mM maltose in purification buffer. AmtR was further purified on a 16/60 Superdex 75 gel-filtration column in a buffer consisting of 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 0.2 M NaCl. The concentration was adjusted to 12 mg ml−1 (Sartorius Vivaspin 500, 10 000 MWCO) for crystallization trials. From a 5 l culture, 14.5 mg pure protein was obtained.

Table 1. Macromolecule-production information.

| Source organism | C. glutamicum ATCC13032 |

| DNA source | C. glutamicum ATCC13032 |

| Expression vector | pMAL |

| Expression host | E. coli BL21 |

| Complete amino-acid sequence of the construct produced | TAGAVGRPRRSAPRRAGKNPREEILDASAELFTRQGFATTSTHQIADAVGIRQASLYYHFPSKTEIFLTLLKSTVEPSTVLAEDLSTLDAGPEMRLWAIVASEVRLLLSTKWNVGRLYQLPIVGSEEFAEYHSQREALTNVFRDLATEIVGDDPRAELPFHITMSVIEMRRNDGKIPSPLSADSLPETAIMLADASLAVLGAPLPADRVEKTLELIKQADAK |

2.2. Crystallization

Native crystals of AmtR were obtained as previously described by mixing 1 µl protein solution (12 mg ml−1 AmtR in 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 0.2 M NaCl) with 1 µl reservoir solution (0.1 M bis-tris pH 5.8, 20% PEG 3350, 0.2 M ammonium sulfate) in a hanging-drop vapour-diffusion setup at 19°C (Hasselt et al., 2009 ▸). Crystallization information is summarized in Table 2 ▸.

Table 2. Crystallization.

| Method | Hanging-drop vapour diffusion |

| Plate type | 24-well |

| Temperature (K) | 293 |

| Protein concentration (mg ml−1) | 12 |

| Buffer composition of protein solution | 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 0.2 M NaCl |

| Composition of reservoir solution | 0.1 M bis-tris pH 5.8, 20% PEG 3350, 0.2 M ammonium sulfate |

| Volume and ratio of drop | 2 µl, 1:1 |

| Volume of reservoir (µl) | 700 |

2.3. Data collection and processing

All crystals were flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen using 20–25% ethylene glycol as a cryoprotectant for data collection at 100 K. MAD data sets and data sets for native AmtR and its complexes were collected on the MX beamlines at the BESSY synchrotron in Berlin (Mueller et al., 2012 ▸, 2015 ▸). The diffraction data were processed using XDS and XSCALE (Kabsch, 2010 ▸). The data-collection statistics are summarized in Table 3 ▸. The statistics for the SAD data set have been reported previously (Hasselt et al., 2009 ▸). AmtR with a molecular mass of 24.4 kDa crystallizes in space group P21212 with six molecules in the asymmetric unit.

Table 3. Data collection and processing.

Values in parentheses are for the outer shell.

| Diffraction source | MX BL14.1, BESSY |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.9184 |

| Temperature (K) | 100 |

| Detector | Rayonics MX-225 3 × 3 CCD |

| Crystal-to-detector distance (mm) | 237.020 |

| Rotation range per image (°) | 0.25 |

| Total rotation range (°) | 100 |

| Exposure time per image (s) | 4.0 |

| Space group | P21212 |

| a, b, c (Å) | 149.8, 160.6, 51.4 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 90, 90 |

| Mosaicity (°) | 0.205 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 33.24–2.09 (2.22–2.09) |

| Total no. of reflections | 300299 |

| No. of unique reflections | 73341 |

| Completeness (%) | 98.8 (95.9) |

| Multiplicity | 4.05 (3.60) |

| 〈I/σ(I)〉 | 13.7 (2.7) |

| R meas (%) | 7.4 (43.7) |

| Overall B factor from Wilson plot (Å2) | 30.7 |

2.4. Structure solution and refinement

Initial model building was achieved using the electron-density maps obtained from the Se-SAD experiment reported previously (Hasselt et al., 2009 ▸). Starting from the previously described data sets, normalized difference structure factors were calculated using SHELXC (Sheldrick, 2008 ▸) and the substructure was solved using SHELXD (Schneider & Sheldrick, 2002 ▸). A first round of phase extension and density modification was carried out using SHELXE (Sheldrick, 2002 ▸). NCS averaging was performed from the heavy-atom positions using RESOLVE (Terwilliger, 2004 ▸). In the improved map, the DNA-binding domain of QacR (PDB entry 1jtx; Schumacher et al., 2001 ▸) and the effector-binding domain dimer of EthR (PDB entry 1t56; Dover et al., 2004 ▸) were placed in order to improve the molecular masks, and further density modification was performed using NCS averaging in DM (Cowtan, 1994 ▸). The NCS-averaged map and the selenium positions allowed the protein to be traced in Coot (Emsley & Cowtan, 2004 ▸) and refined in REFMAC (Murshudov et al., 2011 ▸). This model was subsequently used as a search model in Phaser (McCoy, 2007 ▸) and placed in the unit cell of the native data set, where the a axis was shortened by 3.5 Å in comparison to the Se-SAD data set. The model was refined against F using the TLS and NCS refinement protocol in REFMAC alternating with model building in Coot. Final refinements were carried out using PHENIX (Adams et al., 2010 ▸) and using torsion-based NCS restraints. The structures were validated with MolProbity (Chen et al., 2010 ▸). All structure illustrations were drawn using PyMOL (DeLano, 2003 ▸). Please note that at the time the refined model was obtained, no AmtR structure was yet available in the Protein Data Bank.

3. Results and discussion

The structure of AmtRorth was determined at 2.1 Å resolution in the orthorhombic space group P21212 with six molecules in the asymmetric unit (Table 4 ▸). Each AmtR chain folds into ten α-helices and can be divided into two domains: an N-terminal DNA-binding domain (DBD; helices H1–H3) and a C-terminal effector-binding domain (EBD; helices H4–H10) (Fig. 1 ▸ a). A long loop, L8–9, connecting helices H8 and H9 and the presence of helix H10 distinguish AmtR from other TetR-family members, as observed previously (Palanca & Rubio, 2016 ▸). When analysing the intermolecular contacts between the AmtR chains in the unit cell, only one of the possible contacts yields an assembly with point-group symmetry. AmtR assembles via this contact into homodimers with C 2 symmetry. The chain fold and the dimeric arrangement confer AmtR with the archetypical dimer fold observed in other TetR-family members (Yu et al., 2010 ▸).

Table 4. Structure determination and refinement.

| PDB code | 5mqq |

| Resolution range (Å) | 33.24–2.09 |

| Completeness (%) | 98.8 |

| σ Cutoff | — |

| No. of reflections, working set | 69648 |

| No. of reflections, test set | 3693 |

| Final R work (%) | 20.91 |

| Final R free (%) | 24.97 |

| R work + R free (%) | 21.12 |

| No. of non-H atoms | |

| Protein | 9430 |

| Ligand | 10 |

| Water | 591 |

| Total | 10031 |

| R.m.s. deviations | |

| Bonds (Å) | 0.005 |

| Angles (°) | 0.94 |

| Average B factors (Å2) | |

| Protein | 36.40 |

| Ligand | 35.00 |

| Water | 38.40 |

| Ramachandran plot | |

| Favoured regions (%) | 98.42 |

| Additionally allowed (%) | 1.50 |

| Outliers (%) | 0.08 |

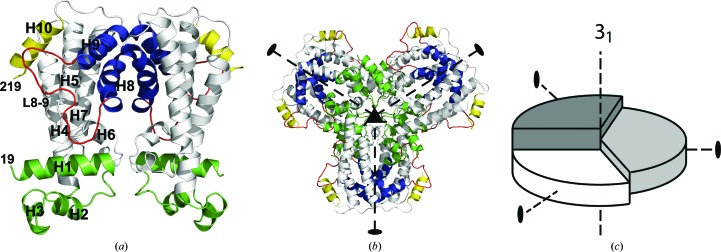

Figure 1.

(a) AmtR dimer, with the DBD shown in green and the dimerization helices in blue. The helices are labelled from H1 to H10. Helix H10 is coloured yellow and loop L8–9 is shown in red. (b) Hexameric assembly formed by a trimer of dimers in the asymmetric unit. (c) Schematic representation of the topology of the hexameric AmtR assembly. The three dimers are shown as segments of a circle in different shades of grey.

It is of interest that AmtR crystallizes with multiple molecules in the asymmetric unit when considering its potential to form higher oligomeric states. The six molecules adopt a pseudo-hexameric assembly formed by three AmtR dimers (Fig. 1 ▸ b). The three dimers can be pairwise superimposed with an average r.m.s.d. of 0.64 Å, showing that the molecules present in the asymmetric unit adopt a highly similar conformation (Fig. 2 ▸ a). However, the hexameric assembly does not display point-group symmetry since the three dimers are related to one another by a noncrystallographic 31 screw axis (Figs. 1 ▸ b and 1 ▸ c). The 31 axis is oriented in the direction of the crystallographic c axis. The twofold axes that relate the monomers in dimeric AmtR in this assembly are oriented perpendicular to the 31 axis. The molecular packing extends beyond the cell boundaries and gives rise to a contiguous helical packing. The helical pitch equals the length of the c axis, and the rise per AmtR dimer is as low as 17.15 Å.

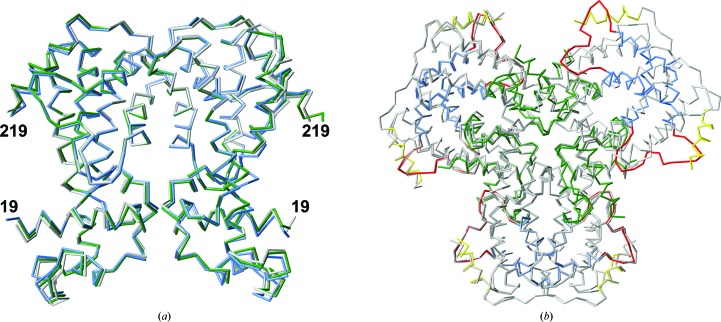

Figure 2.

(a) Superposition of the three AmtR dimers present in AmtRorth on top of each other (in different shades of blue) and of the AmtRtri dimer (shown in green). (b) Superposition of the AmtRorth hexamer (the colour coding is similar to that in Fig. 1 ▸) and the crystallographic AmtRtri hexamer (grey).

A number of AmtR crystal structures have now been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (Berman et al., 2000 ▸). These include crystal structures of AmtR from C. glutamicum in different space groups, namely PDB entries 5dy1 (termed AmtRtri in the current study; 2.65 Å resolution), 5dxz (2.25 Å resolution) and 5dy0 (3.0 Å resolution), which describes an AmtR–DNA complex (Palanca & Rubio, 2016 ▸), as well as the structure of AmtR from Mycobacterium segmatis (PDB entry 5e57; 1.98 Å resolution; Petridis et al., 2016 ▸). Interestingly, a molecular-packing assembly similar to AmtRorth is shared by AmtRtri (Palanca & Rubio, 2016 ▸). The latter crystals contain one AmtR dimer in the asymmetric unit and the helical arrangement is generated by crystallographic 31 screw axes that co-characterize the rhombohedral space group (Fig. 2 ▸). In the hexagonal setting these screw axes are, as in AmtRorth, oriented parallel to the c axis (Supplementary Table S1). The helical rise per dimer is 17.48 Å and is very similar to the rise observed in AmtRorth (17.15 Å). While the above-described contiguous helical packing of AmtR dimers is highly similar in AmtRorth and AmtRtri, differences exist with respect to the interactions that are observed between these helical protein columns. As a result, AmtRorth and AmtRtri display different solvent contents (41.2 and 49.1%, respectively) and adopt different space groups (Supplementary Fig. S1).

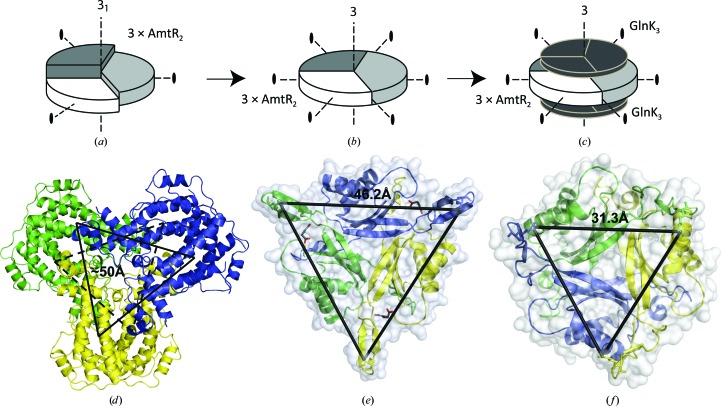

The hexameric assembly of AmtR molecules, as described above, allows a model for the complex formed between dimeric AmtR and trimeric adenylylated GlnK to be postulated. AmtR is no longer able to recognize and bind to its genomic operator sequences when bound to adenylylated GlnK, and therefore the formation of this complex alleviates AmtR-mediated gene repression. The positioning of AmtR dimers along a 31 screw axis with a rise as small as 17.5 Å suggests that slight rearrangements such as a small rotation around the AmtR dimer axis could lead to compaction of the assembly (Figs. 3 ▸ a and 3 ▸ b). As a consequence, the rise would be near zero, the 31 screw axis morphs into a threefold rotation axis and hexameric AmtR adopts D 3 point-group symmetry (Fig. 3 ▸ b). Binding of one GlnK trimer onto each side of the hexameric AmtR assembly would preserve both the C 3 symmetry of GlnK and the symmetry of the AmtR hexamer. The complex would also display D 3 point-group symmetry and adopt a 6:6 (AmtR2)3–(GlnK3)2 stoichiometry (Fig. 3 ▸ c). In support of this model is the observation that the distances between the T-loops (31 and 46 Å; Maier et al., 2011 ▸) in experimental trimeric GlnK structures are similar to the distances between putative effector-binding sites in the proposed hexameric AmtR model (around 50 Å; Figs. 3 ▸ d, 3 ▸ e and 3 ▸ f). Upon the formation of such an (AmtR2)3–(GlnK3)2 complex, the DBDs of AmtR would be oriented towards the centre of the complex and thus preclude DNA binding of AmtR. No AmtR hexamers are observed on the size-exclusion chromatograms (data not shown), and dimeric AmtR is the predominant form in solution. This is in line with the observation that AmtR interacts with DNA operator sequences as a homodimer in the absence of adenylylated GlnK (Palanca & Rubio, 2016 ▸).

Figure 3.

(a) Schematic representation of the topology of the (AmtR2)3 pseudohexamer. The three dimers are shown as segments of a circle in different shades of grey. (b) Schematic representation of the theoretical (AmtR2)3 hexamer following compaction along the former 31 screw axis, which has now morphed into a threefold rotation axis. (c) Schematic representation of the topology of a proposed (AmtR2)3–(GlnK3)2 complex. (d) Ribbon representation of the pseudo-hexameric AmtR dimers, in which each dimer of AmtR is shown in a different colour. Distances between the TetR-type repressor effector-binding sites are marked with black lines. (e, f) The distances between the GlnK T-loops are marked as seen in the crystal structures of GlnK with (e) oxaloacetic acid in the binding pocket (PDB entry 3ta2, 1.9 Å resolution; Maier et al., 2011 ▸) and (f) in complex with E. coli AmtB (PDB entry 2ns1, 1.96 Å resolution; Gruswitz et al., 2007 ▸).

Formation of such a fully symmetrical (AmtR2)3–(GlnK3)2 complex would represent a gene-transcription induction mechanism that has not so far been observed for any other TetR-like repressor. Induction in this family of repressors is considered to occur via an allosteric conformational switch, in which binding of effector molecules to the EBD triggers a separation of the DBDs and as a consequence abolishes DNA binding (Sevvana et al., 2012 ▸). In contrast, induction of AmtR would go in hand with the formation of a 6:6 complex in which the AmtR DBDs become sequestered in the interior of the complex. Nevertheless, also in AmtR, binding of the adenylylated T-loops of GlnK to the EBDs of AmtR might be at the origin of the slight structural rearrangements that are required for the 31 screw-axis symmetry to morph into a threefold axis and thereby allow the formation of an (AmtR2)3–(GlnK3)2 complex. An exact understanding of the details of complex formation, however, must await experimental determination of the complex formed between AmtR and adenylylated GlnK either through structure determination at high resolution via X-ray crystallography and electron microscopy, or the use of low-resolution techniques such as SAXS.

Supplementary Material

PDB reference: AmtR, 5mqq

Supporting Information: Supplementary Figure S1 and Supplementary Table S1.. DOI: 10.1107/S2053230X17002485/wd5273sup1.pdf

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Uwe Müller from Helmholtz-Zentrum Berlin (HZB) at the BESSY synchrotron, Berlin, Germany for help with data collection. We would also like to thank Fabian Gruss (present address: University of Leuven, Belgium) for optimizing the native crystals.

References

- Adams, P. D. et al. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 213–221.

- Amon, J., Titgemeyer, F. & Burkovski, A. (2010). FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 34, 588–605. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Berman, H. M., Westbrook, J., Feng, Z., Gilliland, G., Bhat, T. N., Weissig, H., Shindyalov, I. N. & Bourne, P. E. (2000). Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 235–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chen, V. B., Arendall, W. B., Headd, J. J., Keedy, D. A., Immormino, R. M., Kapral, G. J., Murray, L. W., Richardson, J. S. & Richardson, D. C. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 12–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Conroy, M. J., Durand, A., Lupo, D., Li, X.-D., Bullough, P. A., Winkler, F. K. & Merrick, M. (2007). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 104, 1213–1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cowtan, K. (1994). Jnt CCP4/ESF–EACBM Newsl. Protein Crystallogr. 31, 34–38.

- DeLano, W. (2003). PyMOL. http://www.pymol.org.

- Dover, L. G., Corsino, P. E., Daniels, I. R., Cocklin, S. L., Tatituri, V., Besra, G. S. & Fütterer, K. (2004). J. Mol. Biol. 340, 1095–1105. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Emsley, P. & Cowtan, K. (2004). Acta Cryst. D60, 2126–2132. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Forchhammer, K. (2008). Trends Microbiol. 16, 65–72. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gruswitz, F., O’Connell, J. & Stroud, R. M. (2007). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 104, 42–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hasselt, K., Sevvana, M., Burkovski, A. & Muller, Y. A. (2009). Acta Cryst. F65, 1123–1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Jakoby, M., Krämer, R. & Burkovski, A. (1999). FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 173, 303–310. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kabsch, W. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 125–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Llácer, J. L., Contreras, A., Forchhammer, K., Marco-Marín, C., Gil-Ortiz, F., Maldonado, R., Fita, I. & Rubio, V. (2007). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 104, 17644–17649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Maier, S., Schleberger, P., Lü, W., Wacker, T., Pflüger, T., Litz, C. & Andrade, S. L. (2011). PLoS One, 6, e26327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- McCoy, A. J. (2007). Acta Cryst. D63, 32–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mueller, U., Darowski, N., Fuchs, M. R., Förster, R., Hellmig, M., Paithankar, K. S., Pühringer, S., Steffien, M., Zocher, G. & Weiss, M. S. (2012). J. Synchrotron Rad. 19, 442–449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mueller, U., Förster, R., Hellmig, M., Huschmann, F. U., Kastner, A., Malecki, P., Pühringer, S., Röwer, M., Sparta, K., Steffien, M., Ühlein, M., Wilk, P. & Weiss, M. S. (2015). Eur. Phys. J. Plus, 130, 141.

- Murshudov, G. N., Skubák, P., Lebedev, A. A., Pannu, N. S., Steiner, R. A., Nicholls, R. A., Winn, M. D., Long, F. & Vagin, A. A. (2011). Acta Cryst. D67, 355–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Palanca, C. & Rubio, V. (2016). FEBS J. 283, 1039–1059. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Petridis, M., Vickers, C., Robson, J., McKenzie, J. L., Bereza, M., Sharrock, A., Aung, H. L., Arcus, V. L. & Cook, G. M. (2016). J. Mol. Biol. 428, 4315–4329. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Schneider, T. R. & Sheldrick, G. M. (2002). Acta Cryst. D58, 1772–1779. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Schumacher, M. A., Miller, M. C., Grkovic, S., Brown, M. H., Skurray, R. A. & Brennan, R. G. (2001). Science, 294, 2158–2163. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sevvana, M., Goetz, C., Goeke, D., Wimmer, C., Berens, C., Hillen, W. & Muller, Y. A. (2012). J. Mol. Biol. 416, 46–56. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sheldrick, G. M. (2002). Z. Kristallogr. 217, 644–650.

- Sheldrick, G. M. (2008). Acta Cryst. A64, 112–122. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Strösser, J., Lüdke, A., Schaffer, S., Krämer, R. & Burkovski, A. (2004). Mol. Microbiol. 54, 132–147. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Terwilliger, T. (2004). J. Synchrotron Rad. 11, 49–52. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Yu, Z., Reichheld, S. E., Savchenko, A., Parkinson, J. & Davidson, A. R. (2010). J. Mol. Biol. 400, 847–864. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PDB reference: AmtR, 5mqq

Supporting Information: Supplementary Figure S1 and Supplementary Table S1.. DOI: 10.1107/S2053230X17002485/wd5273sup1.pdf