Abstract

BACKGROUND

Neurons die in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and are not effectively replaced. An alternative approach to maintain nerve cell number is to identify compounds that stimulate the proliferation of endogenous neural stem cells in old individuals to replace lost neurons. However, unless a neurogenic drug is also neuroprotective, the replacement of lost neurons will not be sufficient to stop disease progression.

METHODS

The neuroprotective AD drug candidate J147 is shown to enhance memory, improve dendritic structure, and stimulate cell division in germinal regions of the brains of very old mice. Based upon the potential neurogenic potential of J147, a neuronal stem cell screening assay was developed to optimize derivatives of J147 for human neurogenesis.

RESULTS

The best derivative of J147, CAD-031, maintains the neuroprotective and memory enhancing properties of J147, yet is more active in the human neural stem cell assays.

DISCUSSION

The combined properties of neuroprotection, neurogenesis and memory enhancement in a single drug are more likely to be effective for the treatment of age-associated neurodegenerative disorders than any individual activity alone.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, neurodegenerative disease, aging, neurogenesis, stem cells, neuroprotection, memory enhancement, J147

1. Introduction

Potential Alzheimer’s disease (AD) therapies currently in clinical trials are primarily focused upon the amyloid pathway and do not stimulate the replacement of dead cells in the aged human brain. Even if nerve cells could be replaced, the toxic environment will likely kill new cells unless they are protected. Therefore, drugs that stimulate neurogenesis alone will be ineffective. However, a drug that is both neurogenic and neuroprotective may hold more promise. With the advent of the ability to use human embryonic stem cell-derived (hES) neural precursor cells (hNPCs) as a screen to identify neurogenic compounds, it should be possible to tailor AD drug candidates that are both neurogenic and neuroprotective. This approach has not, however, been previously used to identify an AD drug candidate.

Our laboratory has developed a cell-based phenotypic screening paradigm that mimics multiple age-associated central nervous system (CNS) pathologies [1]. We have successfully identified a number of neuroprotective molecules, including a synthetic derivative of curcumin called J147. J147 facilitates memory in normal rodents and prevents the loss of synaptic proteins and cognitive decline when administered to 3 month old APPswe/PS1ΔE9 mice for 7 months [2]. Furthermore, it has the ability to reverse severe cognitive deficits when fed to very old AD mice [3]. Here, we demonstrate that J147 improved spatial memory using an assay that is widely employed in the clinic, and we show that J147 reduced the loss of dendritic spines in 24 month-old C57Bl/6 mice. Importantly, J147 also stimulated the in vivo proliferation of cells in the dentate gyrus and NPCs within the subventricular zone (SVZ) neural stem cell (NSC) niche, areas of the brain where new nerve cells are born.

Since J147 stimulated cell division within the SVZ in old mice, we hypothesized that it might be possible to optimize J147 for human neurogenesis while maintaining its neuroprotective properties, thus increasing its therapeutic potential. We employed a hES cell-derived hNPC screening paradigm in combination with phenotypic screening assays for old age-associated brain toxicities to synthesize CAD-031. CAD-031 maintains the neuroprotective properties of J147, but is more neurogenic in the hNPC screening assay. The combined properties of neuroprotection, neurogenesis and memory enhancement in a single drug will likely be more effective than a single target compound for the treatment of age-related neurodegenerative disorders like AD that result from the convergence of multiple toxicities.

2. Methods

Animal Studies

Animal studies were carried out in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health. For the aging study, 24 male C57Bl/6 mice aged 24 months were obtained from the National Institute on Aging, Aged Rodent Resource and housed singly. The APPswe/PS1ΔE9 transgenic mice (line 85) carry two transgenes, the mouse/human chimeric APP/Swe, linked to Swedish FAD and human PS1ΔE9 [2, 3]. The J147 diet was prepared by the addition of J147 at 200ppm and control diet was the same food without J147. The Aricept diet was prepared by the addition of CAD-031 at 200ppm and Aricept at 14ppm. All behavioral assays have been extensively detailed in our laboratories [2, 3]. To assay cell proliferation, 5-bromo-2’-deoxyuridine (BrdU) was injected i.p at a concentration of 100mg/kg for 7 days 24hrs after the last BrdU injection mice were euthanized. Cells in the SVZ, were co-stained for BrdU and doublecortin (DCX).

Immunoblotting and Imaging

Tissue preparation, immunohistochemistry and immunoblotting were done as previously described [2, 3].

Golgi Staining

Golgi staining was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (FD NeuroTechnologies). Each dendritic branch was imaged with a through-focus series and stitched together using Axiovision software. The microscopy and computer software were calibrated to measure the length of dendritic branches. Dendritic spines were randomly selected and counted blind.

Neurogenesis Screening Assay

NPCs were made from human embryonic stem cell lines Hues6 and H9 using Embryoid Body (EB) procedures [4]. Experiments were designed so that the drug effect was compared to fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF). Experimental conditions included +FGF, -FGF and –FGF in the presence of drug. Drugs were added at the concentrations and times indicated in the text. Cells were harvested at the time points indicated for qPCR analysis using published primers. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate. Relative gene expression values were analyzed using the SDS software package (version 2.3). GAPDH served as the housekeeping gene and genes were normalized to GAPDH before comparisons were made.

Neuroprotection Assays

HT22 is a hippocampal nerve cell line that is killed by 5 mM glutamate via an oxidative stress-based cell death cascade. MC65 cells are killed by the conditional expression of Aβ. These assays were done as described [1–3].

Chemical Synthesis and Pharmacology

The synthesis of the J147 derivatives and the assays related to the pharmacological properties of CAD-031 are detailed in the Supplemental Material.

3. Results

3.1 J147 enhances memory and dendritic spine number in old mice

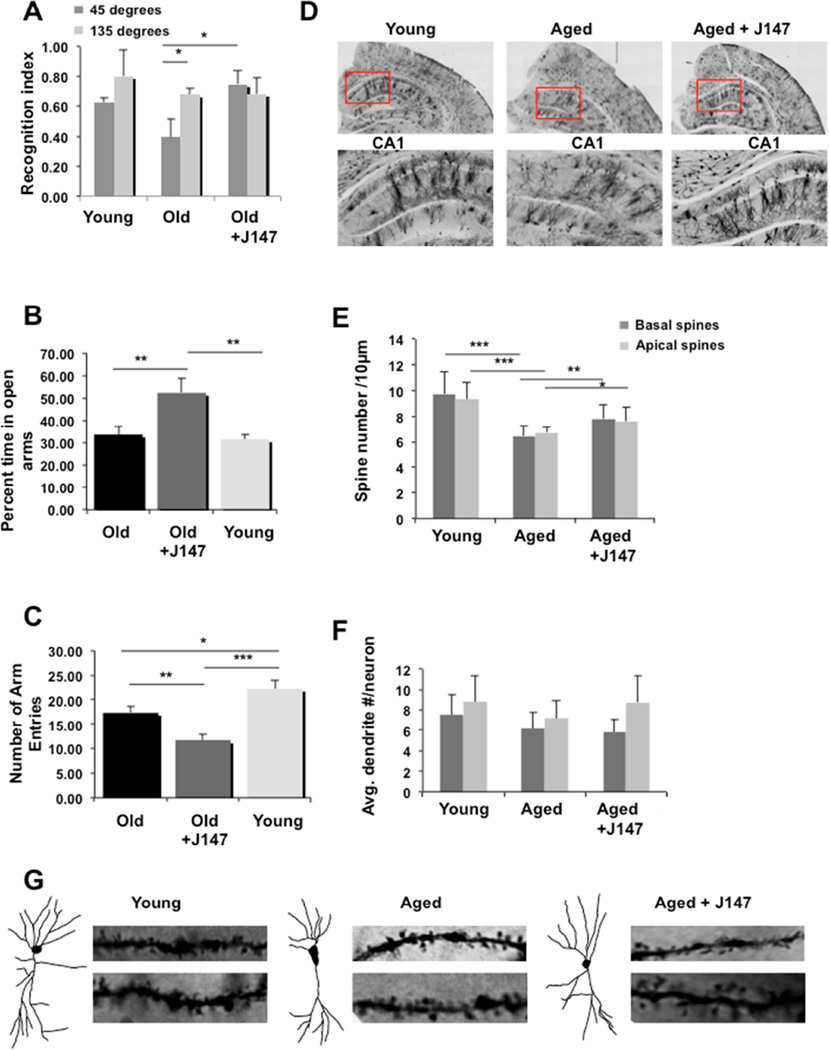

Initially, the behavioral effect of J147 was investigated in aged mice. Pattern separation is a memory assay used in humans to identify cognitive deficits critical to the encoding and retrieval of episodic memories that become reduced with age [5, 6]. Twenty-four month-old male C57Bl/6 mice were treated for 6 months with either J147 chow or normal chow without drug, using 8 month-old mice as controls. While both young and old animals recognized when an object was moved a large distance (135 degrees), a reduction in the recognition index (RI) in aged mice was observed when the object was moved a smaller distance of 45 degrees. The reduction in the RI was reversed upon treatment with J147 (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. J147 Improves Memory and Dendritic Structure in Old C57Bl/6 Mice.

(A–G) Twenty-four month-old mice on control or J147 diet were analyzed for behavior and dendritic spine number after 6 months. (A) Mice were tested for their ability to detect the displacement of a single object moved either 45 or 135 degrees. All mice recognize the object when it has been moved a larger distance (grey bars). Old mice do not recognize the smaller change (black bars) whereas J147 treatment significantly improved the ability of old mice to recognize the change. N=9–12 per group. (B) There was no significant difference between young (light grey bars) and old (black bars) mice in relation to the time spent on the open arms in the EPM. Mice fed J147 spent significantly more time on the open arms. (C) There was a decrease in explorative activity with age, that was negatively affected by J147. N = 11–12. (D) Dendritic spines were analyzed in 30 mo old mice that had been fed control diet or J147 diet for the prior 6 months. Coronal brain sections from a young, aged and an aged mouse treated with J147 are presented, each showing the hippocampus at 10× in the upper panel and the CA1 region highlighted in the box is zoomed in the lower panel. Representative trace images and examples of dendrites with spines from single neurons in each group are shown in (G). (E) The aged mice had significantly fewer apical and basal dendritic spines compared to younger mice and treatment with J147 significantly increased the number of both basal and apical dendritic spines compared to the aged control mice on control diet (n=4 mice per group, 5 neurons per mouse and 8 dendrites per neuron). (F) J147 did not alter basal dendrite number but it increased non-significantly the apical dendrite number. Values are mean ± SD. Tukey-Kramer Multiple Comparisons Test post test *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

Anxiety is another old age-associated behavior that can be assayed using the Elevated Plus Maze (EPM). Young and old mice spent similar amounts of time in the open arms, however, old mice displayed a significant reduction in exploratory activity as evidenced by the reduction in arm entries (Figure 1B–C). J147 significantly increased the time spent in the open arms in aged mice, but did not rescue the reduction in exploratory activity (Figure 1B–C). Therefore, J147 was able to improve memory and decrease anxiety in aged mice.

In addition to a decline in memory with age, there is also damage to the structural integrity of dendrites and spines [7]. Therefore, we asked if J147 affected dendritic structure and spine density in the aged mice. To control for the aging effect, a younger group was included with 2 month-old mice fed control diet for 6 months. Representative images from Golgi stained sections of the hippocampus in each group can be seen in Figure 1D. The CA1 region is highlighted in the red box. Trace images from Golgi stained sections of a single neuron from each condition are shown in Figure 1G, suggesting a more youthful morphology in the J147 treated mice. Directly to the sides of the trace images are dendritic branches showing the spines that were used for quantification. Dendritic spine analysis revealed that aged mice had fewer apical and basal dendritic spines compared to younger mice (Figure 1E). Treatment with J147 significantly increased the number of both basal and apical dendritic spines compared to aged mice on control diet. The average basal dendritic number showed a nonsignificant decrease in aged mice and treatment with J147 did not significantly change this number (Figure 1F).

3.2 J147 stimulates the in vivo proliferation of neural progenitor cells

Neural proliferation is thought to be a contributing factor to cognitive improvements in the pattern separation assay [8]. To address this, aged mice received BrdU injections to detect proliferating cells in the granule cell layer (GCL) and the subgranular zone (SGZ) of the dentate gyrus (DG). There was a significant reduction in BrdU+ cells with age (Figure 2A and B), and treatment with J147 increased this number in aged mice. The proliferative effect of J147 was further confirmed using 6 month-old male mice fed J147 or control diet for 3 mo. Similar to the aged mice, J147 increased the number of BrdU+ cells (Figure 2C). Additionally, the SVZ was examined for neural progenitor proliferation by assessing changes in the percent of BrdU+ cells co-labeled with doublecortin (DCX), a marker for NPCs and immature neurons. The overall number of BrdU+DCX+ cells was significantly increased in J147-treated mice (Figure 2 D and E).

Figure 2. J147 Stimulates Neural Precursor Proliferation.

The mice in Figure 1 were injected with BrdU daily for one week and brain tissue analyzed for the effect of J147 treatment on cell proliferation in the hippocampus and SVZ. (A and B) The number of BrdU+ cells was quantified throughout the hippocampus of four mice per group by spacing sections 240µM apart to represent the entire hippocampus. There was a significant decrease in cell proliferation in old mice vs young, and J147 treatment increased the number of BrdU+ cells in old mice relative to aged matched controls. (C) Six month-old mice were fed J147 for 3 months and the number of BrdU+ cells scored as above. (D) Quantification of proliferating neural progenitor cells (BrdU+DCX+ cells). Values are mean ± SD, n = 12 and 16 SVZs (control and 147-fed mice, respectively), two mice per group, two-tailed unpaired Mann-Whitney t-test, ***p≤0.001. (E) The SVZ of aged mice treated with and without J147 were stained with DAPI (cyan), BrdU (green), DCX (red), and NeuN (blue).

3.3 Drug selection using a human neural stem cell based screening assay

Given the decline in neurogenesis during aging and the proliferative effects of J147 in the hippocampus and SVZ of aged mice, it was asked if J147 could modulate the behavior of hNPCs in vitro and whether this platform could be used to synthesize more potent derivatives of J147 that maintain its neuroprotective properties. Towards this goal, a screening assay was developed using hNPCs to compare the effect of test compounds to that of the FGF requirement for hNPC maintenance [9]. Screening conditions included control cells grown in the presence and absence of FGF, and cells without FGF supplemented with test compounds. The expression of genes involved in neurogenesis was then evaluated by qPCR.

The medicinal chemistry goal was to improve J147’s ability to stimulate neuronal stem cell division while maintaining potency in the neuroprotection assays. The phenyl rings were modified by replacing the metabolically labile methoxy and methyl groups with isosteric groups like -OCF3, -F, and –Cl (Figure 3). These substitutions reduce ring oxidation and subsequent sulfation and glucuronidation that may prevent brain penetration.

Figure 3. The Best Derivatives of J147 in the Neurogenesis Screen.

Scheme showing the modification of the phenyl rings of J147.

New compounds were screened in two neuroprotection assays. The first measures the ability to prevent cell death following the induction of β-amyloid synthesis in the MC65 human CNS nerve cell line [1, 2]. The second utilizes the sensitivity of HT22 hippocampal cells to glutamate toxicity (oxytosis) [1]. Over 200 compounds were synthesized using structure-activity relationship (SAR) driven iterative chemistry and screened in the neuroprotection assays (not shown). Compounds that retained the biological activities and potency of J147 were then screened in the stem cell assays.

The expression of six genes that define various aspects of neurogenesis were evaluated. Nestin and sex determining region Y box-1, and -2 (Sox1 and Sox2) are required for self-renewal, while paired box 6 (Pax6) and DCX are associated with neural progenitor expression and neuronal restriction, respectively [10–13]. We also examined Ki67 as a proliferation marker [13, 14].

Saturating amounts of FGF caused reproducible changes in all six targets relative to controls without FGF and therefore was used to normalize effects of test compounds used at 100nm for 7 days. Our results indicate that the J147 scaffold did not reproducibly alter the expression of Sox1 or Sox2, but did increase transcript expression of Nestin, Pax6, DCX, and Ki67 (Table 1). Several stable compounds were identified, CAD-031, -44, -53 and -57, that had similar or superior activity in the neuroprotection assays and showed significant improvement over J147 in the induction of neurogenesis markers (Table 1). Interestingly, compounds with -OCF3 substitutions on ‘A’ ring (CAD-31, 53 and 57) showed improved neuroprotective activity. Among these, CAD-031 was the most stable in microsomes and plasma (not shown) and the most potent in our hNPC screening assay.

Table 1. J147 Derivatives.

Structure and medicinal chemical properties of the best compounds along with their EC50 values in the neuroprotection assays (MC65 and HT22) and their effect on NPC markers. For the NPC data, qPCR quantified gene expression data are shown for mRNA relative to GAPDH mRNA, which was constant between cultures. The analyses are from 10 independent cultures (5 from each cell line, Hues6 and H9).

| J147 |  |

350 | 41.90 | 4.50 | 10 | 6 | 1.7 | 1 | 0.9 | 1.2 | − | + |

| CAD-031 |  |

404 | 5.91 | 4.79 | 12±2 | 20 | 2.6* | 5.1* | 3 | 5.2* | 1.2* | + |

| CAD-044 |  |

354 | 32.67 | 5.34 | 24±6 | 45 | 1 | 1 | 1.7 | 1.3 | 1.1 | + |

| CAD-053 |  |

376 | 41.9 | 4.54 | 65±5 | 25 | 2.4 | 2.2 | 4.6* | 2.2 | 1.4* | + |

| CAD-057 |  |

394 | 41.9 | 4.83 | 47±10 | 80 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.5* | 1 | 1 | + |

J147 data are expressed as fold increase over FGF.

Fold increase over J147, P<0.01, N=6. Independent cultures Hues6 and H9Combined data. 1 indicates no significant difference over J147.

The pre-clinical screening data in Table S1 show that, like J147, CAD-031 penetrates the brain and has good bioavailability. CAD-031 has no apparent acute mouse toxicity at 2g/kg, with no effect in hERG, Ames and CYP assays at 10 micromolar, standard tests used in the pre-clinical development of drugs to evaluate cardiac safety, mutagenicity and drug metabolism, respectively. CAD-031 was therefore moved forward for testing in an AD mouse model.

3.4 CAD-031 in AD transgenic mice

Female APPswe/PS1ΔE9 transgenic AD mice were used to examine the effect of CAD-031 on the pathological aspects of the disease as well as neural precursor proliferation. Hallmarks of AD are readily apparent at 9 months of age in these mice [15]. At 3 months, mice were randomly assigned to five groups: wild type (WT) Control, WT CAD-031, AD Control and AD CAD-031. CAD-031 was also compared to Aricept, a benchmark standard in clinical trials (AD Aricept). Following 6 months of treatment, all mice were analyzed for hippocampal-associated memory by the fear conditioning and pattern separation tests [8, 16]. AD mice alone spent significantly less time freezing in response to the context associated with the aversive stimulus, indicating that they did not remember the context, a phenotype that was rescued by treatment with CAD-031 (Figure 4A). Mice treated with Aricept also showed a significant increase in the amount of time freezing in response to the context (Figure 4A). There was no significant difference between the wild type and AD controls on Day 3, which is specific for emotional memory [17]. However, treatment with CAD-031, but not Aricept, enhanced the response to the cue in both WT and AD animals (Figure 4B). CAD-031 treatment in AD mice also restored the RI in the hippocampal-dependent spatial pattern separation test (Figure 4C).

Figure 4. CAD-031 in AD Transgenic Mice.

Female AD mice (10 per group) aged 3 mo old were divided into 5 groups; WT Control, WT CAD-031, AD Control, AD CAD-031 and AD Aricept. Treatment with CAD-031 (200ppm) and Aricept (14ppm) continued for 6 mo followed by behavioral testing. Following the last behavioral assay, mice were injected with BrdU daily for one week before sacrifice. (A) AD mice (light colored bars) spent significantly less time freezing in response to the context compared to WT mice (dark bars) on Day 2. Treatment with CAD-031 increased the amount of time AD mice spent freezing suggesting a significant improvement in hippocampal-associated memory. The improvement was comparable to that of Aricept. (B) There was no significant difference in the freezing response on day three (cued memory) between AD and WT control mice but treatment with CAD-031 made both AD and WT mice more sensitive to the cue. (C) There was a significant reduction in the recognition index (RI) with AD, a deficit that was significantly restored by treatment with CAD-031. Aricept also showed a trend towards increased RI but it was not significant. (D) BrdU+ cells were increased in the GCL of the DG by CAD-031 in AD mice. (E) The number of BrdU+ cells was quantified throughout the hippocampus of four mice per group, showing CAD-031 increased their number. (F) Immunohistochemical analysis was done using coronal sections with the antibody 6E10, which is reactive to beta-amyloid. Sections of similar regions from three mice were quantified. One-way ANOVA and Tukey post hoc test were used to determine the statistical significance of the behavioral responses, N=10 per group. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, *** P<0.001.

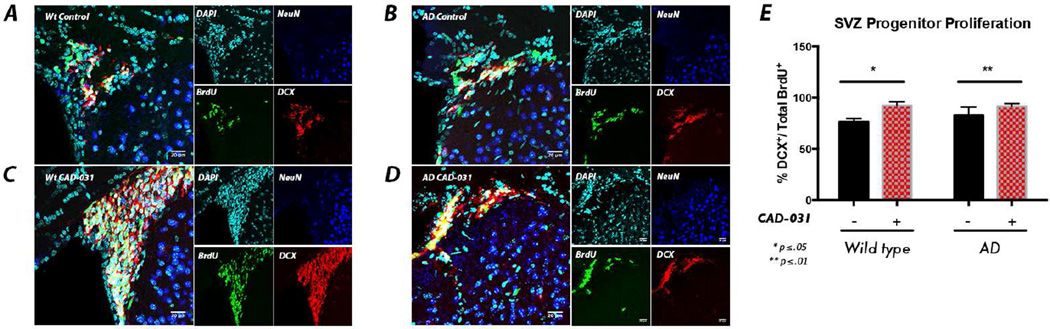

In support for the involvement of a neural precursor proliferative effect of CAD-031 in vivo, the number of BrdU+ cells increased after CAD-031 administration in the GCL of the DG in AD mice (Figure 4D–E). Furthermore, we examined the adult SVZ neural stem cell niche of WT and AD mice stained for BrdU, DCX and neuronal nuclear protein (NeuN) to assess the extent of neural progenitor proliferation. Both WT and AD mice treated with CAD-031 displayed a significant increase in the number BrdU+DCX+ cells compared to mice fed normal chow (Figure 5), indicating enhanced proliferation within the SVZ progenitor compartment. Some compounds that reduce memory loss in AD mice reduce Aβ plaque burden, but there was no difference in either plaque number (Figure 4F) or size (not shown) with CAD-031.

Figure 5. CAD-031 Stimulates Neural Progenitor Proliferation in the SVZ.

(A–D) In the AD study with CAD-031, SVZ coronal sections were stained with DAPI (cyan), BrdU (green), DCX (red), and NeuN (blue). (E) Quantification of proliferating neural progenitors revealed significant increases in neural progenitor proliferation (BrdU+DCX+ cells) between WT mice (A) and WT mice treated with CAD-031 (B). A significant increase in progenitor proliferation was also observed between AD WT mice (C) and AD mice treated with CAD-031 (D). Values are mean ± SD, n = 4 and 12 SVZs (WT and AD mice, respectively), two mice per group, two-tailed unpaired Mann-Whitney t-test, * p≤0.05, **p≤0.01.

4. Discussion

The above data show that a well-studied AD drug candidate, J147, restored the RI in a pattern separation memory assay and reduced anxiety in very old wild type mice. The neuroanatomical basis for the age-related impairment in cognition is likely to depend on the maintenance of synaptic contacts between axonal boutons and dendritic spines [18]. Our data show that there is a significant reduction in both apical and basal dendritic spines in old mice, and are consistent with reports showing that spine density decreases with age in rodents and humans [18]. The degree to which spines are lost correlates with the extent of cognitive impairment [19]. J147 treatment significantly reduced the loss of spines and helped maintain the structural integrity of the dendrites.

Since it had been claimed that positive results in the pattern separation assay could be attributed to increased neural proliferation [8], we assayed cell division in the brain following J147 treatment. J147 stimulated BrdU incorporation in the GCL of the DG of old mice as well as the SVZ relative to age-matched controls. Importantly, there was an increase in the number of BrdU+DCX+ neuronal precursors in the SVZ, suggesting that J147 stimulated the division of stem cells in the nerve cell linage.

Because the development of J147 was based upon rodent neuroprotection assays rather than neurogenesis, we asked if it would be possible to synthesize a derivative tailored to stimulate neurogenesis in human cells. For this purpose, hES-derived NPCs were used as an in vitro model of neurogenesis. Although work with hNPCs has largely focused on their use as a cell replacement therapy, their use as a screening platform is gaining attention [20]. To minimize variability in our hNPC screening model, we compared the effects of test compounds to FGF that is a requirement for NPC maintenance, and assayed gene expression targets specific to neurogenesis.

J147 derivatives were generated using SAR driven iterative medicinal chemistry to improve human neurogenesis while at the same time maintaining the neuroprotective potency and pharmacological properties of J147. We found that the J147 scaffold does not reproducibly alter the expression of early stem cell markers, but does increase the expression of mRNA for proteins associated with neuronal precursor cell division. Of the compounds in a library of over 200 J147 derivatives, four showed significant improvement over J147 in the induction of markers for neurogenesis. The compounds had good physiochemical properties and were also neuroprotective. Of these, CAD-031 has the best pharmacological properties, and was moved forward for testing in an AD mouse model.

The efficacy of CAD-031 was assayed using the traditional preventative strategy, which involved a 6-month CAD-031 treatment starting at 3 months when pathology and cognitive deficits have not yet manifested. The goal was to determine the ability of CAD-031 to reduce cognitive impairment and potentiate neural cell proliferation. In the fear-conditioning assay, AD mice alone spent significantly less time freezing, indicating that they did not remember the context, a phenotype that was rescued by treatment with CAD-031. As with J147 in very old mice, CAD-031 treatment of AD mice also restored the RI of mice in a pattern separation test.

The proliferative effect of CAD-031 was confirmed by an increase in the number of BrdU+ cells in the GCL of the DG. In addition, examination of the BrdU+DCX+ cycling progenitor compartment in the SVZ revealed an increase in progenitor proliferation similar to mice fed J147.

Since CAD-031 is the first compound developed on the basis of its neurogenic and neuroprotective properties, there are some caveats that should be considered related to how it functions in vivo. First, since BrdU immunostaining is only assaying living cells, it is possible that in mice CAD-031 is not causing more cells to divide, but rather preventing the death of precursor cells that would normally die. Second, there is the risk that the stimulation of cell division is not specific to precursor cells and the division of other cells is enhanced. We consider this unlikely since CAD-031 is neither mitogenic for other cell types in culture nor in the brain. Finally, the turnover of cells is required for human health, but the mechanisms that lead to prevention of nerve cell death by CAD-031 must be distinct from all other cell types because there in no evidence for hyperplasia in long term rodent feeding studies.

Ultimately, the only way to determine if a drug candidate is effective is a clinical trial. Although this has been challenging for AD drug candidates because of the high failure rate, both J147 and its derivative CAD-031 are very distinct from the compounds that have thus far failed in the clinic. They are the only compounds that were developed using phenotypic screens for brain toxicities associated with AD. In addition, CAD-031 is both neuroprotective and stimulates the division of human NPCs. It has good pharmacological and medicinal chemical properties and its limited safety profile is excellent (Table S1). Importantly, it is better than Aricept in some memory assays and does not interfere with the function of this widely used drug. While memory enhancement is an FDA-approved drug biomarker for AD, it will be important to identify additional biomarkers for target engagement to support Phase 1 clinical trials. Identifying the molecular target that supports both stem cell division and neuroprotection is the focus of our current work on CAD-031.

In summary, the above data show that a neuroprotective AD drug candidate, J147, not only enhances memory and improves synaptic spine density in very old nontransgenic mice, but also stimulates neuronal stem cell production from hES derived NPCs. Using an in vitro neurogenesis screening approach, a more potently neurogenic derivative of J147 was synthesized and tested in AD mice. This compound, CAD-031, displayed desirable medicinal chemical and pharmacological properties, and also enhanced memory. It also stimulated neural progenitor proliferation in mice. Therefore, the ability to simultaneously potentiate neural progenitor proliferation and provide neuroprotection while enhancing memory may be a useful trait for AD drug candidates.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Phentoypic screening against age-associated dementias used to identify neuroprotective compounds as potential AD drug candidates

J147 enhances memory, improves synaptic spine density, and stimulates neural stem and progenitor cell expansion from hES-derived NPCs.

CAD-031 is a more potent derivative of J147 with enhanced neurogenic potentiation in vitro and in vivo.

The combined properties of an AD drug promoting neurogenic activity as well as neuroprotection hold great promise for future therapies.

Systematic review: A review of the literature indicates that no AD drug candidate has been designed that is both neuroprotective and stimulates neuron replacement. Disease modifying AD drugs developed to date have been unsuccessful in clinical trials, perhaps due to the emphasis on the Aβ pathway. Therefore alternative approaches to AD drug discovery are required.

Interpretation: The manuscript validates the hypothesis that it is possible to make AD drug candidates that are both neuroprotective and potentiate neurogenesis. This first use of both neuroprotection assays and human neural precursor cells as screening platforms to synthesize a new AD drug candidate should make a significant contribution to future AD drug discovery.

Future directions: To provide new therapeutic targets for AD, it will be important to identify the mechanistic pathways underlying the actions of the novel drug candidates described here, and determine if the modulation of these pathways reduces the toxicities responsible for neurodegenerative diseases.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Leah Boyer and Fred Gage for invaluable help with the stem cells and Dr. Pamela Maher for critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank Dr. Fusheng Yang and Ping Ping Chen for help with the brain dissection. The research was supported by grants from the California Institute for Regenerative Medicine (CIRM) (TR3-05669) (DS and MP), the National Institutes of Health (R21NS077201, R01AG046153) (DS), the Fritz B. Burns Foundation (DS), the Bundy Foundation (MP) and The Hewitt Foundation (JG).

Conflict of Interest

Drs. Schubert, Prior and Chiruta are consultants for Abrexa Pharmaceuticals, a virtual company working on the development of J147 for AD.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Prior M, et al. Back to the future with phenotypic screening. ACS Chemical Neuroscience. 2014;5(7):503–513. doi: 10.1021/cn500051h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen Q, et al. A novel neurotrophic drug for cognitive enhancement and Alzheimer's disease. PLoS One. 2011;6(12):e27865. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prior M, et al. The neurotrophic compound J147 reverses cognitive impairment in aged Alzheimer's disease mice. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2013;5(3):25. doi: 10.1186/alzrt179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cowan CA, et al. Derivation of embryonic stem-cell lines from human blastocysts. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(13):1353–1356. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr040330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holden HM, et al. Spatial pattern separation in cognitively normal young and older adults. Hippocampus. 2012;22(9):1826–1832. doi: 10.1002/hipo.22017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wesnes KA, et al. Performance on a pattern separation task by Alzheimer's patients shows possible links between disrupted dentate gyrus activity and apolipoprotein E in4 status and cerebrospinal fluid amyloid-beta42 levels. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2014;6(2):20. doi: 10.1186/alzrt250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dickstein DL, et al. Dendritic spine changes associated with normal aging. Neuroscience. 2013;251:21–32. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.09.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clelland CD, et al. A functional role for adult hippocampal neurogenesis in spatial pattern separation. Science. 2009;325(5937):210–213. doi: 10.1126/science.1173215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vescovi AL, et al. bFGF regulates the proliferative fate of unipotent (neuronal) and bipotent (neuronal/astroglial) EGF-generated CNS progenitor cells. Neuron. 1993;11(5):951–966. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90124-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Graham V, et al. SOX2 functions to maintain neural progenitor identity. Neuron. 2003;39(5):749–765. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00497-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elkouris M, et al. Sox1 maintains the undifferentiated state of cortical neural progenitor cells via the suppression of Prox1-mediated cell cycle exit and neurogenesis. Stem Cells. 2011;29(1):89–98. doi: 10.1002/stem.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park D, et al. Nestin is required for the proper self-renewal of neural stem cells. Stem Cells. 2010;28(12):2162–2171. doi: 10.1002/stem.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gleeson JG, et al. Doublecortin is a microtubule-associated protein and is expressed widely by migrating neurons. Neuron. 1999;23(2):257–271. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80778-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scholzen T, Gerdes J. The Ki-67 protein: from the known and the unknown. J Cell Physiol. 2000;182(3):311–322. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(200003)182:3<311::AID-JCP1>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Savonenko A, et al. Episodic-like memory deficits in the APPswe/PS1dE9 mouse model of Alzheimer's disease: relationships to beta-amyloid deposition and neurotransmitter abnormalities. Neurobiol. Dis. 2005;18(3):602–617. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maren S, Fanselow MS. The amygdala and fear conditioning: has the nut been cracked? Neuron. 1996;16(2):237–240. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80041-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.LeDoux J. The emotional brain, fear, and the amygdala. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2003;23(4–5):727–738. doi: 10.1023/A:1025048802629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nimchinsky EA, Sabatini BL, Svoboda K. Structure and function of dendritic spines. Annu Rev Physiol. 2002;64:313–353. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.64.081501.160008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anderson B, Rutledge V. Age and hemisphere effects on dendritic structure. Brain. 1996;119(Pt 6):1983–1990. doi: 10.1093/brain/119.6.1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klemm M, Schrattenholz A. Neurotoxicity of active compounds--establishment of hESC-lines and proteomics technologies for human embryoand neurotoxicity screening and biomarker identification. ALTEX. 2004;21(Suppl 3):41–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.