This study is the first to use a novel method of atropine infusion directly into the fusiform cell layer of the DCN coupled with simultaneous recordings of neural activity to clarify the contribution of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (mAChRs) to in vivo fusiform cell baseline activity and auditory-somatosensory plasticity. We have determined that blocking the mAChRs increases the synchronization of spiking activity across the fusiform cell population and induces a dominant pattern of inversion in their stimulus timing-dependent plasticity. These modifications are consistent with similar changes established in previous tinnitus studies, suggesting that mAChRs might have a critical contribution in mediating the maladaptive alterations associated with tinnitus pathology. Blocking mAChRs also resulted in decreased fusiform cell spontaneous firing rates, which is in contrast with their tinnitus hyperactivity, suggesting that changes in the interactions between the cholinergic and GABAergic systems might also be an underlying factor in tinnitus pathology.

Keywords: dorsal cochlear nucleus, mAChR, synaptic plasticity

Abstract

Cholinergic modulation contributes to adaptive sensory processing by controlling spontaneous and stimulus-evoked neural activity and long-term synaptic plasticity. In the dorsal cochlear nucleus (DCN), in vitro activation of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (mAChRs) alters the spontaneous activity of DCN neurons and interacts with N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) and endocannabinoid receptors to modulate the plasticity of parallel fiber synapses onto fusiform cells by converting Hebbian long-term potentiation to anti-Hebbian long-term depression. Because noise exposure and tinnitus are known to increase spontaneous activity in fusiform cells as well as alter stimulus timing-dependent plasticity (StTDP), it is important to understand the contribution of mAChRs to in vivo spontaneous activity and plasticity in fusiform cells. In the present study, we blocked mAChRs actions by infusing atropine, a mAChR antagonist, into the DCN fusiform cell layer in normal hearing guinea pigs. Atropine delivery leads to decreased spontaneous firing rates and increased synchronization of fusiform cell spiking activity. Consistent with StTDP alterations observed in tinnitus animals, atropine infusion induced a dominant pattern of inversion of StTDP mean population learning rule from a Hebbian to an anti-Hebbian profile. Units preserving their initial Hebbian learning rules shifted toward more excitatory changes in StTDP, whereas units with initial suppressive learning rules transitioned toward a Hebbian profile. Together, these results implicate muscarinic cholinergic modulation as a factor in controlling in vivo fusiform cell baseline activity and plasticity, suggesting a central role in the maladaptive plasticity associated with tinnitus pathology.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY This study is the first to use a novel method of atropine infusion directly into the fusiform cell layer of the dorsal cochlear nucleus coupled with simultaneous recordings of neural activity to clarify the contribution of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (mAChRs) to in vivo fusiform cell baseline activity and auditory-somatosensory plasticity. We have determined that blocking the mAChRs increases the synchronization of spiking activity across the fusiform cell population and induces a dominant pattern of inversion in their stimulus timing-dependent plasticity. These modifications are consistent with similar changes established in previous tinnitus studies, suggesting that mAChRs might have a critical contribution in mediating the maladaptive alterations associated with tinnitus pathology. Blocking mAChRs also resulted in decreased fusiform cell spontaneous firing rates, which is in contrast with their tinnitus hyperactivity, suggesting that changes in the interactions between the cholinergic and GABAergic systems might also be an underlying factor in tinnitus pathology.

cholinergic modulation mediates attention (Gill et al. 2000; Parikh and Sarter 2008; Witte et al. 1997), sensory cortical plasticity (Bear and Singer 1986; Leach et al. 2013), and learning and memory formation in the hippocampus (Blokland 1995; Compton et al. 1995; Mitsushima et al. 2013). In the basal forebrain, cholinergic neurons promote wakefulness by actions on noncholinergic, neighboring neurons (Li et al. 2009; Yeomans et al. 2006). Common neurophysiological correlates of cholinergic modulation include altered firing rates (Herrero et al. 2008) and changes in the synchronization of neuronal activity between principal neurons (Rodriguez et al. 2004).

The cochlear nucleus (CN), the first brain station of the auditory pathway, is one of many brain regions receiving cholinergic input. Its dorsal division (DCN) mediates sound localization, auditory feature detection, and adaptive filtering of self-generated signals (May 2000; Oertel and Young 2004; Requarth and Sawtell 2011; Roberts and Portfors 2008; Sutherland et al. 1998; Wu et al. 2015b). The principal output neurons of DCN, the fusiform cells, integrate auditory information transduced by the cochlea via auditory nerve fibers synapsing on their basal dendrites and multisensory input relayed by parallel fibers, the axonal projections of the granule cells, synapsing on their apical dendrites (Oertel and Golding 1997l Young and Davis 2002).

Anatomical studies indicate multiple sources of cholinergic projections that could further modulate multisensory integration in fusiform cells. A significant input is provided by projections from medial olivocochlear (MOC) neurons in the superior olivary complex (Benson and Brown 1990; Brown 1993; Mellott et al. 2011; Schofield et al. 2011). These neurons mediate the olivocochlear reflex, which suppresses cochlear outer hair cell responses to alter cochlear amplification (Brown and Levine 2008; Reese et al. 1995; Robertson and Gummer 1985). More recently, substantial cholinergic projections from the pontomesencephalic tegmentum (PMT) to CN were identified (Mellott et al. 2011; Schofield et al. 2011). PMT has also been implicated in multiple functions including arousal, motor control, and sensory gating (Garcia-Rill et al. 2015; Reese et al. 1995; Takakusaki et al. 2015). Thus PMT projections to CN might facilitate integration of sensory stimuli with motor information as well as sensory gating.

Early in vitro studies showed that blocking muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (mAChRs) with atropine substantially decreased the firing activity of a majority of DCN neurons (Chen et al. 1998). Further studies suggested a role for cholinergic input in controlling associative plasticity at the parallel fiber synapses on fusiform cells by converting long-term potentiation (LTP) to long-term depression (LTD), a process also dependent on N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) and endocannabinoid receptors (Zhao and Tzounopoulos 2011). In addition, cholinergic input can modulate the synaptic strength of parallel fiber synapses on cartwheel cells, which provide significant inhibitory drive to the fusiform cells (He et al. 2014). These studies suggest that in vivo cholinergic systems may have a complex effect on fusiform cell activity. Indeed, application of the mAChR agonist carbachol to the DCN surface produced diverse effects on multiunit spontaneous activity, including suppression, activation, or a combination of both (Zhang and Kaltenbach 2000).

Disturbance of the cholinergic modulatory system has been implicated in various pathologies, including schizophrenia and epilepsy (Hillert et al. 2014; Sarter and Bruno 1999; Tani et al. 2015). In DCN, surface application of carbachol suppressed noise-induced enhancements of spontaneous firing in fusiform cells (Manzoor et al. 2013), a well-established tinnitus correlate (Kaltenbach and Afman 2000; Kaltenbach et al. 2004; Wu et al. 2016). Noise exposure and tinnitus were associated with altered fusiform cell plasticity in which tone-evoked learning rules (LRs) induced by stimulus timing-dependent plasticity (StTDP) changed from Hebbian to anti-Hebbian (Koehler and Shore 2013a, 2013b). The molecular mechanisms mediating these changes are yet to be identified.

In this study, we investigate in normal-hearing guinea pigs the contribution of mAChRs to baseline fusiform cell spontaneous activity and StTDP plasticity in vivo. Infusions of atropine into the DCN fusiform cell layer to block mAChRs resulted in decreased spontaneous firing rates (SFRs) and increased synchronization of fusiform cell spontaneous spiking activity. Furthermore, atropine resulted in significant alteration in StTDP-induced LRs in fusiform cells, with a dominant transition from Hebbian to anti-Hebbian LRs. In addition, units preserving their initial Hebbian LRs showed a shift toward more excitatory StTDP, and units with initial suppressive LRs transitioned toward Hebbian profiles. Changes in synchronization of spontaneous activity and StTDP plasticity are consistent with those identified in tinnitus (Koehler and Shore 2013a; Wu et al. 2015a), suggesting that mAChRs could have an important role in tinnitus pathology.

METHODS

Six normal-hearing guinea pigs (Elm Hill colony; Ann Arbor, MI; 300–400 g) were used in this study. All procedures were performed in accordance with the “Guide for the Use and Care of Laboratory Animals” (NIH Publication No. 80-23) and were approved by the University Committee on Use and Care of Animals of the University of Michigan.

Auditory Brain Stem Response Recordings

Auditory brain stem response (ABR) thresholds were determined in anesthetized guinea pigs (see Surgical Methods) immediately before unit recordings. ABRs were collected using BioSigRP software and RA4LI/RX8/RZ2 hardware [Tucker-Davis Technologies (TDT), Alachua, FL]. Stimuli were 10-ms tone pips (2-ms ramp, 11 stimuli/s), starting at 90 dB SPL and decrementing in 10-dB steps (512 repetitions per level) from 4 to 20 kHz with 2 kHz per step. For each frequency, ABR waveforms were visually inspected and the threshold was determined as the lowest sound level for which the ABR waves were distinguishable by eye from background noise. All the guinea pigs in this study had normal hearing thresholds (Djalilian and Cody 1973; Ingham et al. 1998) across all frequencies tested.

Surgical Methods

Guinea pigs were anesthetized with subcutaneous injections of ketamine (40 mg/kg; Putney, Portland, OR) and xylazine (10 mg/kg; Lloyd). The animals’ heads were rigidly fixed in a Kopf stereotaxic frame with hollow ear bars placed in their ear canals and secured with a bite bar. Rectal temperature was maintained at 38 ± 0.5°C using a rectal probe and a temperature control heating pad. The animals’ eyes were protected with sterile ophthalmic ointment (LubriFresh; Major Pharmaceuticals, Livonia, MI). A rostral-caudal incision was made immediately after local subcutaneous injection of lidocaine (4 mg/kg), and the skin was retracted to reveal the skull. A small craniotomy (0.5 cm) followed by durotomy was performed, and the brain was covered with two to three drops of mineral oil to maintain homeostatic conditions.

Drug Delivery of mAChR Antagonist to DCN

A 1-shank, 16-site neuroprobe with integrated drug delivery interface (D16; NeuroNexus, Ann Arbor, MI) was connected to a 10-µl syringe loaded with an 80 µM solution of the mAChR antagonist atropine. The syringe was rigidly fixed to a digitally controlled electric pump (UMP3 microsyringe injector with Micro4 controller; World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL). This system allows simultaneous drug delivery and recordings of neural activity as described and validated in previous studies (Rohatgi et al. 2009; Stefanescu and Shore 2015). Following craniotomy and durotomy, the neuroprobe was inclined at 25° and inserted stereotaxically into the left DCN, 4 mm caudal to the interaural zero, 3 mm lateral to the midline, and 5.5–6 mm in depth (see Fig. 1A for a schematic representation). Further displacements in depth were made in steps of 100–200 µm until signatures of cartwheel cell activity were identified on the lower electrodes and 10–30 µm afterwards until a majority of the recording sites were positioned in the fusiform cell layer as indicated by extracellular recordings of robust responses to noise stimuli and characteristic responses to BF tones (1,000 trials, each of 50-ms noise/tone stimuli with 5-ms ramp; see Fig. 1B for typical examples). This position of the probe was then maintained for the duration of the experiment. After initial assessment of baseline fusiform cell activity and StTDP (see more details below), 2 µl of an 80 µM atropine solution were delivered into the fusiform cell layer with a velocity of 100 nl/min (optimal for this configuration; Rohatgi et al. 2009; Stefanescu and Shore 2015). The concentration of the atropine solution used in this study was chosen on the basis of previous findings suggesting that lower concentration might not have a significant effect of fusiform cell spontaneous activity (Manzoor et al. 2013).

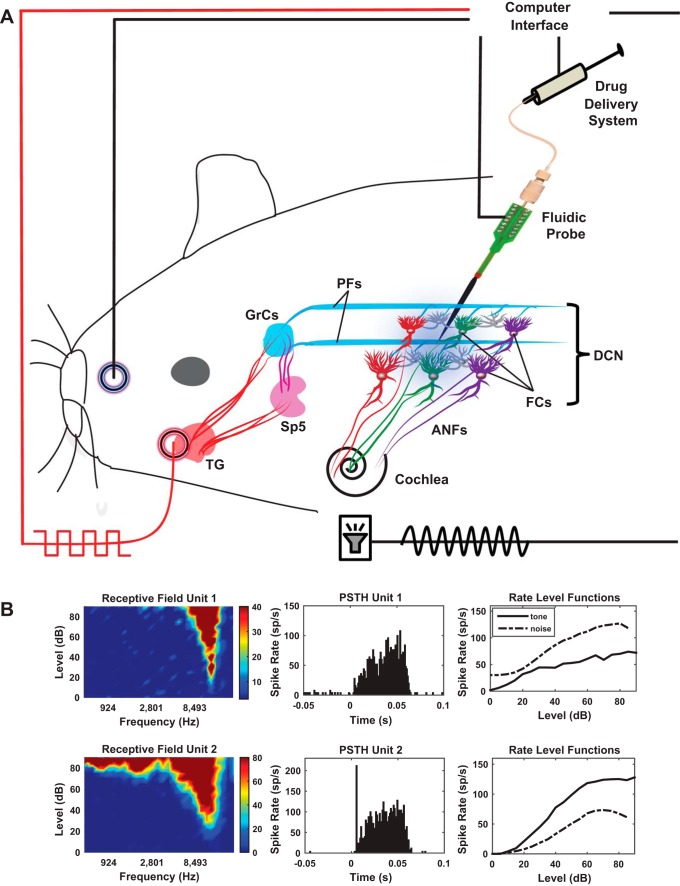

Fig. 1.

Schematic of the experimental setup. A: auditory stimulation delivered to the guinea pig cochlea through a hollow ear bar activates the auditory nerve fibers (ANFs) and DCN fusiform cells via ANF synapses on fusiform cell basal dendrites. Electrical pulses on the face activate the somatosensory pathway to the DCN by stimulating the trigeminal ganglion (TG) and spinal trigeminal nucleus (SP5) projections to the granule cells (GrCs), which relay their output to the fusiform cells via parallel fibers (pfs) that synapse on their apical dendrites. For bimodal stimulation, somatosensory stimulation is delivered in precise temporal proximity with the auditory stimulation. The neural activity is recorded with a fluidic probe. Baseline fusiform cell activity and plasticity were evaluated before and after delivery of a mAChR blocker (atropine, 80 µM, 2 µl, 100 nl/min) in the fusiform cell layer. B: examples of characteristic responses of fusiform cells: receptive fields, peristimulus time histograms, and noise and tone rate-level functions were recorded before the experiment to characterize the type of the fusiform cells. Shown are 2 examples of the most common unit types recorded, a build-up type III (top row) and a pause build-up type I (bottom row).

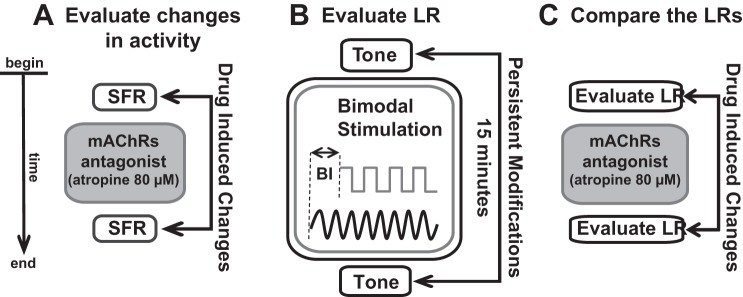

Baseline fusiform cell activity and StTDP were then reevaluated and compared with the responses obtained before the antagonist delivery to assess the effect of blocking mAChRs (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Schematic of the stimulation and recording protocol. A: baseline spontaneous activity and synchrony were recorded before and after atropine delivery. B: bimodal auditory-somatosensory stimulation was employed to elicit stimulus time-dependent plasticity (StTDP) of fusiform cell tone-evoked responses. Tones at fusiform cell best frequency and electrical somatosensory stimulation pulses were delivered at specific onset differences, i.e., a bimodal interval (BI) in the range of tens of milliseconds. Tone-evoked activity was recorded before and after bimodal stimulation to evaluate the learning rule (LR) of each fusiform cell. C: the contribution of mAChRs to fusiform cell plasticity was assessed by comparing the LRs elicited by the bimodal stimulation protocol before and after atropine delivery. The LR evaluation before and after atropine followed the procedure presented in brief in B. For A–C, the time flow of the experiment is in the vertical, downward direction as indicated by the arrow at far left.

Facial Electrical Stimulation

After the left cheek and nose of each guinea pig were shaved, a stimulating electrode pad was placed on the left cheek, superficial to the masseter muscle, while a ground electrode pad (10-mm diameter, Ag-AgCl BraiNet electrode; RhythmLink) was placed on the nasal bridge (see Fig. 1A for an illustration). Electrode gel (Parker Laboratories, Fairfield, NJ) facilitated optimal current delivery. Biphasic (100 µs/phase) current pulses at 1,000 Hz (2.2-ms total duration) were delivered at current intensities that evoked fusiform cell spikes above spontaneous rate and did not evoke contractions of the facial muscles (2–5 mA). When combined with sound stimulation, this transcutaneous stimulation induces StTDP in the DCN (Wu et al. 2015a).

Assessment of Responses to Auditory Stimulation

Receptive fields were constructed by counting the spikes produced in response to 7,600 tone bursts over an intensity range of 0–90 dB (in steps of 5 dB) and a frequency range of 100 Hz–24 kHz (in 0.2-octave steps), from which threshold and best frequency (BF) were assessed for each cell. Tone and noise rate-level functions (RLFs) and peristimulus time histograms (PSTHs) were collected to determine the unit type on the basis of previously described criteria (Ding and Voigt 1997; Evans and Nelson 1973; Rhode et al. 1983; Stabler et al. 1996; Wu et al. 2016; Young 1980; Young and Brownell 1976). The tones were generated using OpenEX and Rx8 DSP systems (TDT) and delivered to the left ear canal via a hollow ear bar by an attached shielded speaker (DT770; Beyer) driven by an HB7 amplifier (TDT). Sound levels were adjusted with a programmable attenuator (PA5; TDT) previously calibrated for equal levels at frequencies between 100 Hz and 24 kHz. Units were classified as fusiform cells on the basis of their PSTH shapes and RLFs to BF tones and noise (Fig. 1B).

Synchrony of Spontaneous Firing Activity

Synchrony between fusiform cells was assessed as previously (Wu et al. 2016). Briefly, spontaneous spiking activity was recorded continuously for 2.5 min before and after atropine delivery (Fig. 2A). Synchrony between units was evaluated as described previously (Eggermont 1992; Voigt and Young 1980, 1990; Wu et al. 2016). Common spikes within ±150 µs on different electrodes were eliminated to avoid data contamination with possible artificial correlations (Brody 1999). Units with mean SFRs of <1 Hz were excluded from this analysis. For each pairwise combination of spike trains, the peak cross-correlation coefficients ρ(τ) were computed for each time lag (τ) according to Eq. 1 (Abeles 1982; Eggermont 1992):

| (1) |

where RAB is the unbiased cross-correlation of spike trains A and B with NA and NB number of spikes, E = NANB/N is the expectancy of spike train coincidence under the assumption of independence, and N is the number of bins. The time lags analyzed were between −20 and +20 ms. The bin size was 0.3 ms (Voigt and Young 1990; Wu et al. 2016). Unit pairs exhibited synchrony when the correlation coefficient ρ(τ) exceeded four standard deviations from the mean ρ across all time lags considered. Each unit was paired with another single unit, and all possible combinations were evaluated. Synchronization between any two units was reported just once, and only the pairs of units showing synchronization before and after atropine delivery were used in the analysis. Units that showed initial correlations that disappeared after atropine delivery due to a marked decrease in their firing rate were excluded from this analysis.

StTDP Assessment

StTDP was assessed using a bimodal auditory-somatosensory stimulation protocol previously described and validated in guinea pig (Koehler and Shore 2013a, 2013b; Wu et al. 2015a). Briefly, BF tone-evoked responses were recorded before and 15 min after bimodal stimulation. The bimodal stimulation consisted of 300 trials (200 ms/trial) of 50-ms BF tones and transcutaneous facial stimulation (100 µs/phase) presented at 1 Hz with an intertone interval of 100 ms. The onset difference between tone presentation and face stimulation defines the bimodal interval (BI). In this study, the BI was assigned randomly to one of four possible values (−20, −10, +10, and +20 ms). Negative BI values indicate sound presentation leading face stimulation (−20 and −10), whereas positive BI values (+10 and +20 ms) correspond to face stimulation leading sound presentation (Fig. 2B). After the assessment of StTDP-induced LRs, atropine was delivered and the LRs were reassessed. LRs were classified into four distinct profiles (Hebbian, anti-Hebbian, suppressive, and enhancing) using the same quantitative criteria as in Stefanescu et al. (2015), in agreement with other similar in vivo studies (Koehler and Shore 2013a, 2013b; Stefanescu and Shore 2015; Wu et al. 2015a, 2016a).

The contribution of mAChRs to StTDP-induced plasticity was assessed by comparing the LRs obtained before and after atropine delivery (Fig. 2C).

Data Analysis

Spike detection and sorting.

Waveforms from each electrode site were digitized using a PZ2 preamplifier (Fs = 12 kHz; TDT) and bandpass filtered (300 Hz–3 kHz). Online spike detection (RZ2 module; TDT) used a voltage threshold of 2.5 SD from the background noise, and the resulting timestamps and waveform snippets were saved on a personal computer. Offline Sorter software (Plexon) was used to manually cluster the waveforms on the basis of their similarity in the first three principal components. The clusters representing single-unit activity were tracked for consistency across recordings during the StTDP protocol. The timestamps of the sorted units were imported in MATLAB for further analysis.

Statistical analysis.

The Kruskal-Wallis test (with statistical significance set at 0.05) was used to evaluate the statistically significant changes in SFR. One-way ANOVA (with statistical significance set at 0.05) was used to evaluate the statistically significant changes in synchronization strength following atropine delivery. Two-way ANOVA with drug and BI as factors was used to evaluate the effects of atropine on fusiform cells changing or preserving their LRs, respectively. Subsequent post hoc one-way ANOVA tests with Bonferroni correction were used to assess the significant differences induced by atropine for each BI. The statistical significance was set at 0.05.

RESULTS

Effect on Baseline Activity

Blocking mAChRs reduced fusiform cell spontaneous firing rates.

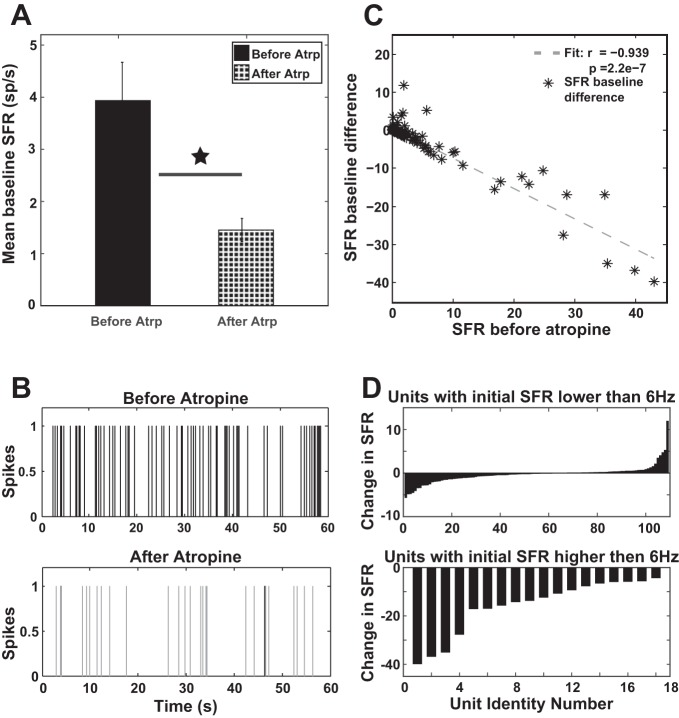

Spontaneous firing rate (SFR) of 129 fusiform units was evaluated before and after atropine delivery. The mean SFR was significantly lower after mAChRs were blocked (Fig. 3A; Kruskal-Wallis test, χ2 = 4.67, P = 0.0306). A representative example of altered spiking activity following atropine delivery is given in Fig. 3B. The SFR difference induced by atropine negatively correlated with the initial baseline SFR (r = −0.939; P = 2.2e-7). Thus the higher the initial SFR of a fusiform cell, the more the cell decreased its mean spontaneous spiking activity after atropine delivery (Fig. 3C). For units with initial lower values of SFR (<6 Hz), atropine could either increase (in 42 units, or 38%) or decrease (in 68 units, or 62%) their firing rates, respectively (Fig. 3D, top). In contrast, units with higher initial SFRs (>6 Hz) showed a consistent, significant decrease in SFR following atropine application (see Fig. 3D, bottom; Kruskal-Wallis test, χ2 = 17.18, P = 3.4e-05). Together, these results suggest that atropine decreases fusiform cell spontaneous firing rates, especially in units with initial higher SFRs.

Fig. 3.

Spontaneous firing rate (SFR) is decreased following atropine delivery. A: mean baseline SFR is significantly reduced following atropine delivery (Kruskal-Wallis test, χ2 = 4.67, P = 0.0306; star indicates the statistical significance). Vertical bars indicate SE. B: examples of firing activity patterns recorded in a fusiform unit before (top) and after (bottom) atropine delivery. Marked decreases of spiking activity can be observed after blocking of mAChRs. C: The difference in SFR (SFR after − SFR before atropine) is negatively correlated with the initial value of the baseline SFR (r = −0.939, P = 2.2e-7). D: in units with initial lower SFR (<6 Hz; top), atropine can either decrease or increase SFR; in contrast, atropine significantly decreases SFR in units with initial higher SFRs (bottom).

Blocking mAChRs enhanced spontaneous spike synchronization between fusiform cells.

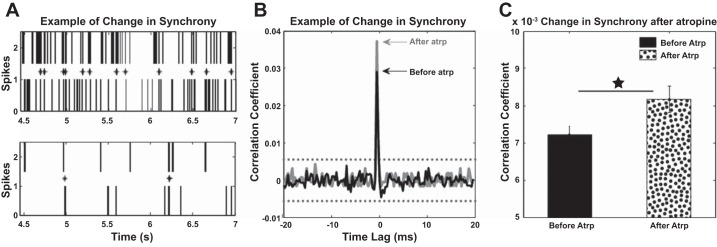

Synchrony of fusiform cell spiking activity was assessed before and after delivery of mAChR antagonist by using a pairwise spike train correlation metric (see methods) previously established in the auditory cortex and DCN (Noreña and Eggermont 2003; Voigt and Young 1988, 1990; Wu et al. 2016). Although most individual pairs decreased the number of synchronized spikes, they also decreased their overall spontaneous firing rate (see Fig. 4A for an example), which led to an increase of the correlation coefficient as evaluated by the correlation metric (Fig. 4B). Forty-two distinct pairs of units showed significant synchronization before atropine delivery, but afterward there was an increased correlation coefficient. The synchronization strength indicated by the mean correlation coefficient across the neural population increased significantly [1-way ANOVA, F(1) = 4.84, P = 0.0263] following atropine delivery (Fig. 4C). No significant correlations between previously uncorrelated pairs of neurons could be identified.

Fig. 4.

Fusiform cell synchronization is increased after atropine delivery. A: example of spike synchronization before (top) and after (bottom) atropine delivery. Although the number of coincident spikes is decreasing, there is also a decrease of the overall firing rate of the fusiform cells, which leads to an increase in the correlation coefficient used as metric of synchronization (see B). B: the correlation coefficient before atropine delivery (black) is increased after the mAChRs are blocked (gray) with no change in the synchronization time lag. Confidence boundaries (95%) are indicated by the horizontal black dashed lines. C: mean synchronization across the entire neural population (42 pairs of units with significant correlation coefficients) before atropine delivery is significantly increased after atropine [1-way ANOVA, F(1) = 4.84, P = 0.0263; star indicates the statistical significance]. Vertical bars indicate SE.

Blocking mAChRs Alters StTDP

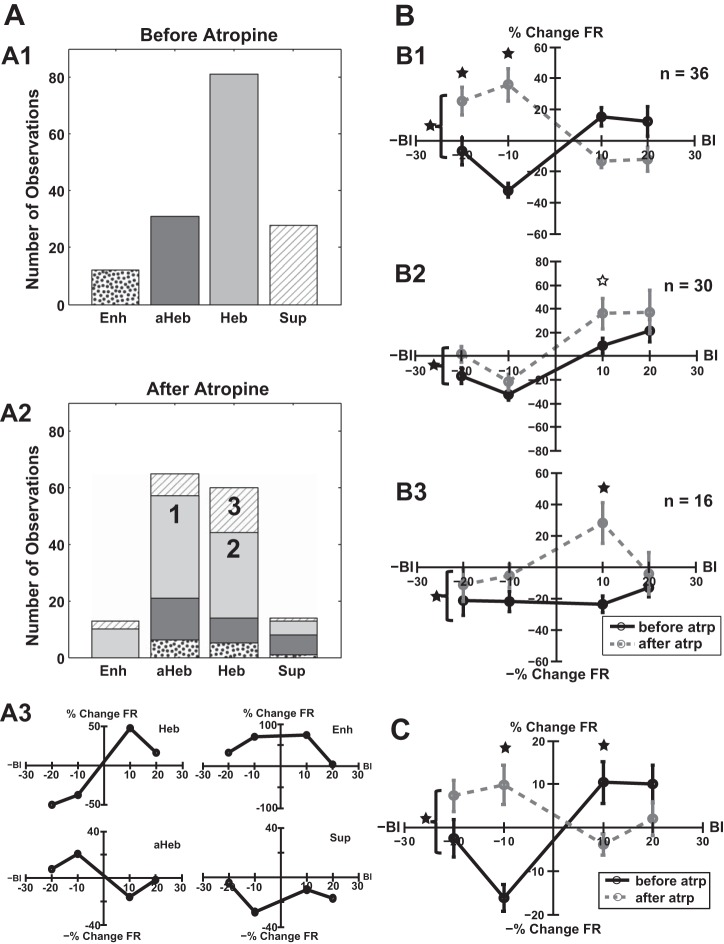

Consistent with previous observations (Koehler and Shore 2013a, 2013b), before atropine delivery, the distribution of StTDP LRs (for long tones) induced in the entire fusiform cell neural population was dominated by Hebbian plasticity (Fig. 5A1, light gray bars), whereas anti-Hebbian Fig. 5A1, dark gray bars) and suppressive LRs (Fig. 5A1, hatched bars) were less dominant. A few units showed enhancing LRs (Fig. 5A1, dotted bars). After atropine delivery, three significant patterns of change in the LRs were identified:

Fig. 5.

Atropine alters StTDP in fusiform cells. A1: before atropine delivery, the distribution of StTDP-induced LRs across the entire fusiform cell population is dominated by Hebbian LRs (Heb; light gray) followed by anti-Hebbian (aHeb; dark gray), suppressive (Sup; hatching), and enhancing LRs (Enh; dotted). A2: after atropine delivery, 3 significant patterns of changes in the LRs could be identified: 36 units (24%) showed transitions from Hebbian to anti-Hebbian profiles (1), 30 units (20%) preserved their initial Hebbian LR profile (2), and 16 units (10%) with initial suppressive LRs transitioned toward Hebbian profiles (3). A3: examples of basic LR patterns recorded in individual fusiform cells before atropine delivery. B: for each significant pattern of change induced by atropine delivery, mean subpopulation LRs are presented before (black lines) and after atropine delivery (dashed gray lines) as follows: transition from Hebbian to anti-Hebbian plasticity (B1), shift toward excitatory StTDP for units preserving their Hebbian LR profiles (B2), and transitions from suppressive to Hebbian profiles (B3) driven by significant changes (solid black stars) in the plasticity induced for a BI = +10 ms. C: across the entire fusiform cell population, the initial Hebbian mean population LR (black line) changed significantly toward an anti-Hebbian profile (dashed gray line) after atropine delivery due to the dominant pattern explained in B1. Significant differences (2-way ANOVA test, P = 1.04e-06) in the mean LRs are indicated by solid black stars. For each BI, statistically significant differences (1-way ANOVA post hoc tests with Bonferroni correction, BI = −10 ms, P = 1.7e-05; BI = +10 ms, P = 0.048) are indicated with vertically aligned solid black stars. A statistical trend (P = 0.065) was observed for BI = +10 ms in B2 and is indicated by the open star.

A majority of 36 units (24%) showed significant transitions from their initial Hebbian to anti-Hebbian LR profiles (Fig. 5A2, light gray bars, and 5B1). Two-way ANOVA indicated significance for the drug factor [F(1) = 4.48, P = 0.0352] and for interaction between drug and BI [F(3) = 17.59, P = 1.85e-10]. Post hoc tests (see methods, Statistical analysis) indicated significant differences induced by atropine for BI = −20 ms [F(1) = 6.62, P = 0.049] and BI = −10 ms [F(1) = 5.89, P = 2.36e-07]. This pattern dominated the changes in StTDP plasticity across the entire fusiform cell neural population [2-way ANOVA interactions between BI and drug factors, F(3) = 10.32, P = 1.043e-6; Fig. 5C]. Atropine delivery resulted in significant differences in the mean population LRs for BI = −10 ms [F(1) = 21.95, P = 1.7e-05] but also for BI = +10 ms [F(1) = 6.38, P = 0.048].

Twenty percent of the units preserved their initial Hebbian LRs following atropine delivery. Nonetheless, there was a significant shift of their mean LR toward increased StTDP-induced changes (Fig. 5A2, light gray bars, and 5B2). Two-way ANOVA indicated a significant effect for drug factor [F(1) = 6.58, P = 0.011]. The difference was more pronounced for BI = +10 ms, for which a statistical trend could be identified [F(1) = 3.53, P = 0.065].

A smaller group of 16 units (10%) with initial suppressive LRs showed transitions toward a Hebbian profile (Fig. 5A2, hatched bars, and 5B3). Two-way ANOVA indicated statistical significance for the drug factor [F(1) = 10.49, P = 0.0016]. Post hoc tests revealed that this change is largely driven by the StTDP change occurring for the BI of +10 ms [F(1) = 13.82, P = 0.0034].

DISCUSSION

In this study, we analyzed the contribution of mAChRs in vivo to baseline spiking activity and StTDP-induced plasticity in DCN fusiform cells. We showed that atropine decreases the mean SFR of the fusiform cell population. In contrast, the synchronization of fusiform cells spontaneous activity increased following atropine delivery. The major pattern of change in StTDP-induced plasticity was a change from Hebbian to anti-Hebbian LR profiles, but some neurons shifted toward more excitatory StTDP changes for the units, preserving their Hebbian LR profiles, and a smaller number changed from suppressive to Hebbian profiles. The first pattern dominates the changes in plasticity as reflected by the transition of the mean LR of the entire fusiform cell population from Hebbian to anti-Hebbian profiles.

Changes in Spontaneous Activity

Early in vitro studies implicated mAChRs in modulating the spontaneous activity of DCN neurons (Chen et al. 1994, 1998). Atropine was found to substantially decrease the SFRs of a majority of DCN neurons (Chen et al. 1998) in vitro, whereas carbachol, a mAChR agonist, increased the firing rates of the regularly firing neurons (including fusiform cells) and had a variable effect on bursting neurons (likely cartwheel cells), where increased neural firing rates were followed by a decrease in half of the responsive neurons (Chen et al. 1994).

Follow-up studies also demonstrated in vivo cholinergic modulation of spontaneous activity in DCN (Zhang and Kaltenbach 2000). Application of carbachol to the surface of the DCN induced diverse, dose-dependent changes in multiunit activity characterized by suppression, activation, or a combination of both (two-component responses; Zhang and Kaltenbach 2000). Such complex modulatory effects are likely to arise from differential cholinergic modulation of fusiform and cartwheel cell activity and its further interaction with the inhibition the cartwheel cells exert on fusiform cells (Chen et al. 1999).

In the current study, by infusing atropine into the fusiform cell layer as confirmed by physiological identification of fusiform units (see methods), we were able to further clarify the contribution of mAChRs to fusiform cell SFR. Blocking mAChRs resulted in a significant decrease in fusiform cell baseline SFRs (Fig. 3A). The higher the initial firing rate, the more it decreased after atropine delivery.

Changes in Synchronization

In the cortex, cholinergic modulation contributes to information processing by desynchronizing the local field potentials and decorrelating unit responses through the activation of a specific class of interneurons (Chen et al. 2015). However, the opposite effect was also observed (Rodriguez et al. 2004). For instance, in the visual cortex, application of muscarinic cholinergic agonists enhances stimulus-driven synchronization and gamma oscillations (Rodriguez et al. 2004). Computational studies suggest that these effects can be explained by differential synchronization of inhibitory networks controlling the activity of the principal neurons in the visual cortex (Tiesinga and Sejnowski 2004).

Similar selective interactions between cholinergic input and inhibitory neural activity was identified in the hippocampus, where it modulated synchronization underlying theta and gamma rhythms (Chapman and Lacaille 1999; Fellous and Sejnowski 2000; Lawrence 2008). Interestingly, there are two forms of hippocampal theta rhythms (Buzsáki et al. 1983): an atropine-sensitive form mediated by differential distribution of muscarinic receptor on different types of inhibitory cells (Cea-del Rio et al. 2010; Lawrence et al. 2006) and an atropine-resistant form mediated primarily by α7- and α4-nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) (Garcia-Rill 1991; Gillies et al. 2002; Rohleder et al. 2014).

In the DCN, cholinergic activation is mediated primarily by M1/M3 muscarinic receptors on the postsynaptic terminal of the parallel fiber synapses on fusiform cells (Zhao and Tzounopoulos 2011) and by M2/M4 on the dendrites of cartwheel cells (He et al. 2014), and α7-nAChR is robustly expressed in the molecular and fusiform cell layer of the DCN (Yao and Godfrey 1999). Our results indicate that blocking mAChRs in DCN leads to increased synchronization of fusiform cell spontaneous activity (Fig. 4). Decreased firing activity lowers the number of concurrent spikes across the fusiform cell population, but it also lowers the expectancy of spike coincidence and increases the significance of the positive observations (due to decreased values of NA and NB; see Eq. 1 in methods). This process can be viewed as a reduction in the noisy spiking activity of the fusiform cells in favor of a more significant activity. It is possible that, similarly to cortex (Winn 2006) and hippocampus (Garcia-Rill 1991), this effect could be the result of interactions between the nAChRs and GABAergic inhibitory activity mediated by the cartwheel cells. Such interactions could also decrease the SFR of fusiform cells, explaining therefore the opposite effects of increased synchronization of spontaneous activity but reduced SFR observed across the fusiform cell population.

Changes in StTDP-Induced Plasticity

In vitro activation of M1/M3 mAChRs interacts with NMDA and endocannabinoid receptors to convert Hebbian LTP to anti-Hebbian LTD (Zhao and Tzounopoulos 2011), by controlling the strength and polarity of parallel fiber-fusiform plasticity (Zhao and Tzounopoulos 2011). The distribution of mAChRs on the fusiform cell apical dendritic trees is currently unknown. Moreover, parallel fiber-to-cartwheel cell synapses also express mAChRs. Thus their anti-Hebbian plasticity (Tzounopoulos et al. 2004) could further modulate fusiform-cell plasticity. The effect of mAChRs on cartwheel cells plasticity is unknown.

The current study clarifies the effect of mAChR blockage on the fusiform cell StTDP. The main pattern of change induced by atropine delivery was a transition from Hebbian to anti-Hebbian LRs (Fig. 5B1), which dominates the plasticity of the fusiform cell population (Fig. 5C). Interestingly, this transition pattern has been also observed when the NMDA receptors are blocked (Stefanescu and Shore 2015), further establishing a common mechanism and interaction between these receptors in controlling fusiform cell plasticity in vivo.

Implications for Tinnitus

Sound overexposure and tinnitus are associated with heightened fusiform cell SFR (Kaltenbach and Afman 2000; Kaltenbach et al. 2004; Koehler and Shore 2013a; Li et al. 2013; Wu et al. 2016), inversions in StTDP-induced plasticity (Koehler and Shore 2013a; Koehler and Shore 2013b; Stefanescu et al. 2015), and increased synchrony and bursting (Wu et al. 2016). Cholinergic modulation was revealed as a contributing factor in vivo by studies showing that carbachol application on the DCN surface reduces fusiform cell SFRs (Manzoor et al. 2013). Our results indicate that blocking mAChRs in normal-hearing animals leads to reduction of fusiform cell SFR, which is in agreement with in vitro observations (Chen et al. 1998) but in apparent contradiction with effects of cholinergic modulation in noise-exposed animals. A possible explanation for this discrepancy is a difference in the molecular pathways activated by the cholinergic input in normal-hearing and tinnitus animals. In normal-hearing animals, cholinergic activation may interact with GABAergic inhibition to control fusiform cell activity (Wedemeyer et al. 2013). In tinnitus animals, a reduction of GABAergic inhibition (Middleton et al. 2011) may alter this interaction and possibly lead to fusiform cell hyperactivity. These mechanisms, however, need to be clarified by future studies.

In addition to changes in spontaneous fusiform cell activity, in vivo studies demonstrated inversions in StTDP LRs following noise exposure and tinnitus (Koehler and Shore 2013a; 2013b). Consistent with these results, we found that blocking mAChRs leads to inversion from Hebbian to anti-Hebbian LRs, which adds to the accumulating evidence that mAChRs contribute to tinnitus pathology.

Noise overexposure and tinnitus were shown to increase choline acetyl transferase activity in CN (Jin et al. 2006), suggesting an upregulation of cholinergic receptors in DCN (Takakusaki et al. 2015). However, it is currently unclear which type of cholinergic receptors are upregulated and on what type of DCN cells. Our results indicate that blocking mAChRs induces changes in the fusiform cell baseline activity and plasticity consistent with those observed in tinnitus animals. This suggests the possibility that in DCN, the nAChRs might be more strongly upregulated than mAChRs following noise overexposure and tinnitus. Consequently, our results suggest that agonizing mAChRs and/or blocking nAChRs in the DCN might be a worthy potential therapeutic strategy for tinnitus pathology.

GRANTS

This research was funded by National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders Grants R01DC004825 (to S. E. Shore) and P30DC05188.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

R.A.S. performed experiments; R.A.S. and S.E.S. analyzed data; R.A.S. and S.E.S. interpreted results of experiments; R.A.S. prepared figures; R.A.S. drafted manuscript; R.A.S. and S.E.S. edited and revised manuscript; R.A.S. and S.E.S. approved final version of manuscript; S.E.S. conceived and designed research.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Sandy Bledsoe for help with the preparation of the solutions used in this study and for excellent comments and suggestions. We thank Calvin Wu for editorial help and useful comments. We also thank James Wiler for technical assistance with the surgeries performed in this study.

REFERENCES

- Abeles M. Local Cortical Circuits. Berlin: Springer, 1982. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-81708-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bear MF, Singer W. Modulation of visual cortical plasticity by acetylcholine and noradrenaline. Nature 320: 172–176, 1986. doi: 10.1038/320172a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson TE, Brown MC. Synapses formed by olivocochlear axon branches in the mouse cochlear nucleus. J Comp Neurol 295: 52–70, 1990. doi: 10.1002/cne.902950106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blokland A. Acetylcholine: a neurotransmitter for learning and memory? Brain Res Brain Res Rev 21: 285–300, 1995. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(95)00016-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody CD. Correlations without synchrony. Neural Comput 11: 1537–1551, 1999. doi: 10.1162/089976699300016133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MC. Fiber pathways and branching patterns of biocytin-labeled olivocochlear neurons in the mouse brainstem. J Comp Neurol 337: 600–613, 1993. doi: 10.1002/cne.903370406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MC, Levine JL. Dendrites of medial olivocochlear neurons in mouse. Neuroscience 154: 147–159, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.12.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzsáki G, Leung LW, Vanderwolf CH. Cellular bases of hippocampal EEG in the behaving rat. Brain Res 287: 139–171, 1983. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(83)90037-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cea-del Rio CA, Lawrence JJ, Tricoire L, Erdelyi F, Szabo G, McBain CJ. M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor expression confers differential cholinergic modulation to neurochemically distinct hippocampal basket cell subtypes. J Neurosci 30: 6011–6024, 2010. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5040-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman CA, Lacaille JC. Cholinergic induction of theta-frequency oscillations in hippocampal inhibitory interneurons and pacing of pyramidal cell firing. J Neurosci 19: 8637–8645, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, Waller HJ, Godfrey DA. Cholinergic modulation of spontaneous activity in rat dorsal cochlear nucleus. Hear Res 77: 168–176, 1994. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(94)90264-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, Waller HJ, Godfrey DA. Effects of endogenous acetylcholine on spontaneous activity in rat dorsal cochlear nucleus slices. Brain Res 783: 219–226, 1998. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(97)01348-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, Waller HJ, Godfrey TG, Godfrey DA. Glutamergic transmission of neuronal responses to carbachol in rat dorsal cochlear nucleus slices. Neuroscience 90: 1043–1049, 1999. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4522(98)00503-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen N, Sugihara H, Sur M. An acetylcholine-activated microcircuit drives temporal dynamics of cortical activity. Nat Neurosci 18: 892–902, 2015. doi: 10.1038/nn.4002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton DM, Dietrich KL, Smith JS, Davis BK. Spatial and non-spatial learning in the rat following lesions to the nucleus locus coeruleus. Neuroreport 7: 177–182, 1995. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199512000-00043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding J, Voigt HF. Intracellular response properties of units in the dorsal cochlear nucleus of unanesthetized decerebrate gerbil. J Neurophysiol 77: 2549–2572, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djalilian M, Cody DTR. Averaged cortical responses evoked by pure tones in the chinchilla and the guinea pig. Arch Otolaryngol 98: 196–200, 1973. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1973.00780020204013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggermont JJ. Neural interaction in cat primary auditory cortex. Dependence on recording depth, electrode separation, and age. J Neurophysiol 68: 1216–1228, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans EF, Nelson PG. The responses of single neurones in the cochlear nucleus of the cat as a function of their location and the anaesthetic state. Exp Brain Res 17: 402–427, 1973. doi: 10.1007/BF00234103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fellous J-M, Sejnowski TJ. Cholinergic induction of oscillations in the hippocampal slice in the slow (0.5–2 Hz), theta (5–12 Hz), and gamma (35–70 Hz) bands. Hippocampus 10: 187–197, 2000. doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Rill E. The pedunculopontine nucleus. Prog Neurobiol 36: 363–389, 1991. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(91)90016-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Rill E, Luster B, D’Onofrio S, Mahaffey S, Bisagno V, Urbano FJ. Pedunculopontine arousal system physiology – Deep brain stimulation (DBS). Sleep Sci 8: 153–161, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.slsci.2015.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill TM, Sarter M, Givens B. Sustained visual attention performance-associated prefrontal neuronal activity: evidence for cholinergic modulation. J Neurosci 20: 4745–4757, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillies MJ, Traub RD, LeBeau FE, Davies CH, Gloveli T, Buhl EH, Whittington MA. A model of atropine-resistant theta oscillations in rat hippocampal area CA1. J Physiol 543: 779–793, 2002. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.024588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He S, Wang YX, Petralia RS, Brenowitz SD. Cholinergic modulation of large-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels regulates synaptic strength and spine calcium in cartwheel cells of the dorsal cochlear nucleus. J Neurosci 34: 5261–5272, 2014. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3728-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrero JL, Roberts MJ, Delicato LS, Gieselmann MA, Dayan P, Thiele A. Acetylcholine contributes through muscarinic receptors to attentional modulation in V1. Nature 454: 1110–1114, 2008. doi: 10.1038/nature07141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillert MH, Imran I, Zimmermann M, Lau H, Weinfurter S, Klein J. Dynamics of hippocampal acetylcholine release during lithium-pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus in rats. J Neurochem 131: 42–52, 2014. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingham NJ, Thornton SK, Comis SD, Withington DJ. The auditory brainstem response of aged guinea pigs. Acta Otolaryngol 118: 673–680, 1998. doi: 10.1080/00016489850183160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Y-M, Godfrey DA, Wang J, Kaltenbach JA. Effects of intense tone exposure on choline acetyltransferase activity in the hamster cochlear nucleus. Hear Res 216–217: 168–175, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenbach JA, Afman CE. Hyperactivity in the dorsal cochlear nucleus after intense sound exposure and its resemblance to tone-evoked activity: a physiological model for tinnitus. Hear Res 140: 165–172, 2000. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5955(99)00197-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenbach JA, Zacharek MA, Zhang J, Frederick S. Activity in the dorsal cochlear nucleus of hamsters previously tested for tinnitus following intense tone exposure. Neurosci Lett 355: 121–125, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koehler SD, Shore SE. Stimulus timing-dependent plasticity in dorsal cochlear nucleus is altered in tinnitus. J Neurosci 33: 19647–19656, 2013a. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2788-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koehler SD, Shore SE. Stimulus-timing dependent multisensory plasticity in the guinea pig dorsal cochlear nucleus. PLoS One 8: e59828, 2013b. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence JJ. Cholinergic control of GABA release: emerging parallels between neocortex and hippocampus. Trends Neurosci 31: 317–327, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence JJ, Statland JM, Grinspan ZM, McBain CJ. Cell type-specific dependence of muscarinic signalling in mouse hippocampal stratum oriens interneurones. J Physiol 570: 595–610, 2006. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.100875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leach ND, Nodal FR, Cordery PM, King AJ, Bajo VM. Cortical cholinergic input is required for normal auditory perception and experience-dependent plasticity in adult ferrets. J Neurosci 33: 6659–6671, 2013. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5039-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Du Y, Li N, Wu X, Wu Y. Top-down modulation of prepulse inhibition of the startle reflex in humans and rats. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 33: 1157–1167, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Choi V, Tzounopoulos T. Pathogenic plasticity of Kv7.2/3 channel activity is essential for the induction of tinnitus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 9980–9985, 2013. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1302770110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzoor NF, Chen G, Kaltenbach JA. Suppression of noise-induced hyperactivity in the dorsal cochlear nucleus following application of the cholinergic agonist, carbachol. Brain Res 1523: 28–36, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2013.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May BJ. Role of the dorsal cochlear nucleus in the sound localization behavior of cats. Hear Res 148: 74–87, 2000. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5955(00)00142-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellott JG, Motts SD, Schofield BR. Multiple origins of cholinergic innervation of the cochlear nucleus. Neuroscience 180: 138–147, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton JW, Kiritani T, Pedersen C, Turner JG, Shepherd GM, Tzounopoulos T. Mice with behavioral evidence of tinnitus exhibit dorsal cochlear nucleus hyperactivity because of decreased GABAergic inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 7601–7606, 2011. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100223108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsushima D, Sano A, Takahashi T. A cholinergic trigger drives learning-induced plasticity at hippocampal synapses. Nat Commun 4: 2760, 2013. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noreña AJ, Eggermont JJ. Changes in spontaneous neural activity immediately after an acoustic trauma: implications for neural correlates of tinnitus. Hear Res 183: 137–153, 2003. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5955(03)00225-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oertel D, Golding N. Circuits of the dorsal cochlear nucleus. In: Acoustical Signal Processing in the Central Auditory System, edited by Syka J. New York: Plenum, 1997, p. 127–138. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-8712-9_12. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oertel D, Young ED. What’s a cerebellar circuit doing in the auditory system? Trends Neurosci 27: 104–110, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parikh V, Sarter M. Cholinergic mediation of attention: contributions of phasic and tonic increases in prefrontal cholinergic activity. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1129: 225–235, 2008. doi: 10.1196/annals.1417.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reese NB, Garcia-Rill E, Skinner RD. The pedunculopontine nucleus–auditory input, arousal and pathophysiology. Prog Neurobiol 47: 105–133, 1995. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(95)00023-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Requarth T, Sawtell NB. Neural mechanisms for filtering self-generated sensory signals in cerebellum-like circuits. Curr Opin Neurobiol 21: 602–608, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2011.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhode WS, Smith PH, Oertel D. Physiological response properties of cells labeled intracellularly with horseradish peroxidase in cat dorsal cochlear nucleus. J Comp Neurol 213: 426–447, 1983. doi: 10.1002/cne.902130407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts PD, Portfors CV. Design principles of sensory processing in cerebellum-like structures. Early stage processing of electrosensory and auditory objects. Biol Cybern 98: 491–507, 2008. doi: 10.1007/s00422-008-0217-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson D, Gummer M. Physiological and morphological characterization of efferent neurones in the guinea pig cochlea. Hear Res 20: 63–77, 1985. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(85)90059-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez R, Kallenbach U, Singer W, Munk MH. Short- and long-term effects of cholinergic modulation on gamma oscillations and response synchronization in the visual cortex. J Neurosci 24: 10369–10378, 2004. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1839-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohatgi P, Langhals NB, Kipke DR, Patil PG. In vivo performance of a microelectrode neural probe with integrated drug delivery. Neurosurg Focus 27: E8, 2009. doi: 10.3171/2009.4.FOCUS0983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohleder C, Jung F, Mertgens H, Wiedermann D, Sué M, Neumaier B, Graf R, Leweke FM, Endepols H. Neural correlates of sensorimotor gating: a metabolic positron emission tomography study in awake rats. Front Behav Neurosci 8: 178, 2014. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarter M, Bruno JP. Abnormal regulation of corticopetal cholinergic neurons and impaired information processing in neuropsychiatric disorders. Trends Neurosci 22: 67–74, 1999. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(98)01289-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield BR, Motts SD, Mellott JG. Cholinergic cells of the pontomesencephalic tegmentum: connections with auditory structures from cochlear nucleus to cortex. Hear Res 279: 85–95, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2010.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stabler SE, Palmer AR, Winter IM. Temporal and mean rate discharge patterns of single units in the dorsal cochlear nucleus of the anesthetized guinea pig. J Neurophysiol 76: 1667–1688, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanescu RA, Koehler SD, Shore SE. Stimulus-timing-dependent modifications of rate-level functions in animals with and without tinnitus. J Neurophysiol 113: 956–970, 2015. doi: 10.1152/jn.00457.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefanescu RA, Shore SE. NMDA receptors mediate stimulus-timing-dependent plasticity and neural synchrony in the dorsal cochlear nucleus. Front Neural Circuits 9: 75, 2015. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2015.00075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland DP, Masterton RB, Glendenning KK. Role of acoustic striae in hearing: reflexive responses to elevated sound-sources. Behav Brain Res 97: 1–12, 1998. doi: 10.1016/S0166-4328(98)00008-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takakusaki K, Chiba R, Nozu T, Okumura T. Brainstem control of locomotion and muscle tone with special reference to the role of the mesopontine tegmentum and medullary reticulospinal systems. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 123: 695–729, 2015. doi: 10.1007/s00702-015-1475-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tani M, Akashi N, Hori K, Konishi K, Kitajima Y, Tomioka H, Inamoto A, Hirata A, Tomita A, Koganemaru T, Takahashi A, Hachisu M. Anticholinergic Activity and Schizophrenia. Neurodegener Dis 15: 168–174, 2015. doi: 10.1159/000381523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiesinga PH, Sejnowski TJ. Rapid temporal modulation of synchrony by competition in cortical interneuron networks. Neural Comput 16: 251–275, 2004. doi: 10.1162/089976604322742029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzounopoulos T, Kim Y, Oertel D, Trussell LO. Cell-specific, spike timing-dependent plasticities in the dorsal cochlear nucleus. Nat Neurosci 7: 719–725, 2004. doi: 10.1038/nn1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voigt HF, Young ED. Evidence of inhibitory interactions between neurons in dorsal cochlear nucleus. J Neurophysiol 44: 76–96, 1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voigt HF, Young ED. Neural correlations in the dorsal cochlear nucleus: pairs of units with similar response properties. J Neurophysiol 59: 1014–1032, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voigt HF, Young ED. Cross-correlation analysis of inhibitory interactions in dorsal cochlear nucleus. J Neurophysiol 64: 1590–1610, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wedemeyer C, Zorrilla de San Martín J, Ballestero J, Gómez-Casati ME, Torbidoni AV, Fuchs PA, Bettler B, Elgoyhen AB, Katz E. Activation of presynaptic GABAB(1a,2) receptors inhibits synaptic transmission at mammalian inhibitory cholinergic olivocochlear-hair cell synapses. J Neurosci 33: 15477–15487, 2013. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2554-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winn P. How best to consider the structure and function of the pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus: evidence from animal studies. J Neurol Sci 248: 234–250, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2006.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witte EA, Davidson MC, Marrocco RT. Effects of altering brain cholinergic activity on covert orienting of attention: comparison of monkey and human performance. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 132: 324–334, 1997. doi: 10.1007/s002130050352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C, Martel DT, Shore SE. Transcutaneous induction of stimulus-timing-dependent plasticity in dorsal cochlear nucleus. Front Syst Neurosci 9: 116, 2015a. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2015.00116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C, Martel DT, Shore SE. Increased synchrony and bursting of dorsal cochlear nucleus fusiform cells correlate with tinnitus. J Neurosci 36: 2068–2073, 2016. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3960-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu C, Stefanescu RA, Martel DT, Shore SE. Listening to another sense: somatosensory integration in the auditory system. Cell Tissue Res 361: 233–250, 2015b. doi: 10.1007/s00441-014-2074-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao W, Godfrey DA. Immunolocalization of α4 and α7 subunits of nicotinic receptor in rat cochlear nucleus. Hear Res 128: 97–102, 1999. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5955(98)00199-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeomans JS, Lee J, Yeomans MH, Steidl S, Li L. Midbrain pathways for prepulse inhibition and startle activation in rat. Neuroscience 142: 921–929, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young ED. Identification of response properties of ascending axons from dorsal cochlear nucleus. Brain Res 200: 23–37, 1980. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)91091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young ED, Brownell WE. Responses to tones and noise of single cells in dorsal cochlear nucleus of unanesthetized cats. J Neurophysiol 39: 282–300, 1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young ED, Davis KA. Circuitry and function of the dorsal cochlear nucleus. In: Integrative Functions in the Mammalian Auditory Pathway, edited by Oertel D, Fay RR, and Popper AN. New York: Springer, 2002, p. 160–206. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-3654-0_5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang JS, Kaltenbach JA. Modulation of spontaneous activity by acetylcholine receptors in the rat dorsal cochlear nucleus in vivo. Hear Res 140: 7–17, 2000. doi: 10.1016/S0378-5955(99)00181-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Tzounopoulos T. Physiological activation of cholinergic inputs controls associative synaptic plasticity via modulation of endocannabinoid signaling. J Neurosci 31: 3158–3168, 2011. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5303-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]