Abstract

Background:

Best practice recommendations for sports-related emergency preparation include implementation of venue-specific emergency action plans (EAPs), access to early defibrillation, and first responders—specifically coaches—trained in cardiopulmonary resuscitation and automated external defibrillator (AED) use. The objective was to determine whether high schools had implemented these 3 recommendations and whether schools with a certified athletic trainer (AT) were more likely to have done so.

Hypothesis:

Schools with an AT were more likely to have implemented the recommendations.

Study Design:

Cross-sectional study.

Level of Evidence:

Level 4.

Methods:

All Oregon School Activities Association member school athletic directors were invited to complete a survey on sports-related emergency preparedness and AT availability at their school. Chi-square and Fisher exact tests were used to analyze the associations between emergency preparedness and AT availability.

Results:

In total, 108 respondents (37% response rate) completed the survey. Exactly half reported having an AT available. Only 11% (95% CI, 6%-19%) of the schools had implemented all 3 recommendations, 29% (95% CI, 21%-39%) had implemented 2, 32% (95% CI, 24%-42%) had implemented 1, and 27% (95% CI, 19%-36%) had not implemented any of the recommendations. AT availability was associated with implementation of the recommendations (χ2 = 10.3, P = 0.02), and the proportion of schools with ATs increased with the number of recommendations implemented (χ2 = 9.3, P < 0.01). Schools with an AT were more likely to implement venue-specific EAPs (52% vs 24%, P < 0.01) and have an AED available for early defibrillation (69% vs 44%, P = 0.02) but not more likely to require coach training (33% vs 28%, P = 0.68).

Conclusions:

Despite best practice recommendations, most schools were inadequately prepared for sports-related emergencies. Schools with an AT were more likely to implement some, but not all, of the recommendations. Policy changes may be needed to improve implementation.

Clinical Relevance:

Most Oregon high schools need to do more to prepare for sports-related emergencies. The results provide evidence for sports medicine professionals and administrators to inform policy changes that ensure the safety of athletes.

Keywords: sudden death, sudden cardiac arrest, prehospital emergency care, athlete injury

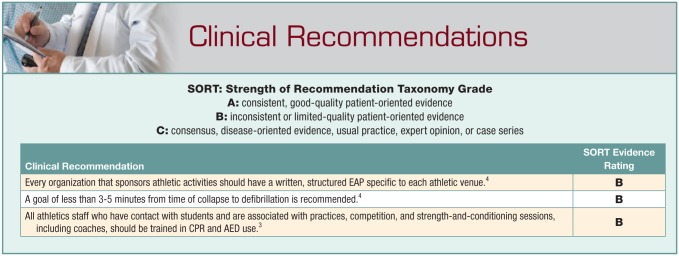

Participation in high school sports involves an inherent risk of catastrophic injury. Although such events are rare, institutions must be prepared to respond. Timely care decreases the risk of death or permanent disability for the athlete, as well as the emotional toll of a young person’s death or catastrophic injury on family, friends, and the school community. Furthermore, emergency preparation is essential for an institution to reduce the risk of litigation for negligence should a catastrophic event occur.3 To aid preparedness for sports-related emergencies, multiple national organizations have defined institutional best practices.1,3,4,7

A written emergency action plan (EAP) details the standard of care during emergency situations at all venues where catastrophic injury can occur.1,3,4,7,15,16 While a number of reports exist on EAP adoption by high schools,9,12,14,17,23,25 only 1 addressed whether EAPs were available at all venues.14

While EAPs define roles and guide appropriate actions for emergencies, another key element is the availability of the lifesaving equipment to carry out the plan. For instance, it is crucial that sudden cardiac arrest is immediately recognized, the EAP is activated, and early cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and rapid defibrillation occur.4,7,19,24 Survival rates after ventricular fibrillation decrease 7% to 10% for every minute defibrillation is delayed8; hence, access to an automated external defibrillator (AED) is essential. While many researchers have documented AED presence on campus,10,12,14,17,21,23,25 only 2 studies specifically examined AED availability for early defibrillation.14,23

Finally, the availability of trained individuals is essential for execution of the EAP. Ideally, the institution would have an onsite healthcare professional, such as an athletic trainer (AT), available to provide care during all sports-related emergencies as well as to assist the institution plan for emergency situations. While many advocate for an AT be present at least at high-risk sports events in case of emergency,3,5,16 only 70% of high schools nationally provide any form of AT services to student-athletes.18 Additionally, even in schools with an AT, he or she will not always be available for immediate emergency care because of multiple teams practicing at various times and locations. In these cases, persons such as other team members, administrators, or spectators could provide emergency care, but in the majority of instances, a coach will most likely serve in this role. Therefore, it has been advocated that all coaches be trained in CPR and AED use.3 However, a review of state high school activities association websites found that only 40% of schools require coaches to be CPR-certified, and even fewer require AED training.

The foundation of emergency preparation includes having (1) a detailed response plan (EAP) ready, (2) life-saving equipment—specifically an AED—available, and (3) coaches trained in CPR and AED use. Having all 3 elements coordinated together should improve immediate care and result in better patient outcomes. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to determine the proportion of high schools in Oregon that had implemented these 3 best-practice components of emergency planning and whether implementation was associated with AT presence in a given school.

Methods

This study used a cross-sectional design to assess AT availability and sports-related emergency preparedness in Oregon high schools. The study was classified “exempt” by the Oregon State University Institutional Review Board.

In February 2014, email invitations were sent to all 292 Oregon School Activities Association member school athletic directors (ADs) inviting them to complete a web-based survey (Qualtrics, LLC) on their school’s planning for athletic emergencies. Follow-up invitations were sent in March and April. The survey was developed to assess implementation of published emergency planning recommendations.1,3 Survey content is detailed in Supplementary Table 1 (available at http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/suppl/10.1177/1941738116686782).

There were 3 binary outcomes. To be considered to have met best practice recommendations, ADs had to answer that (1) venue-specific EAPs were available, (2) the school had an AED available for early defibrillation at all athletic venues, and (3) coaches were required to complete training in both CPR and AED use.

Descriptive statistics are reported as proportions with 95% CIs. A chi-square (χ2) test was used to analyze the association between overall emergency planning best practices and AT availability in Oregon high schools. Individual elements of the best practice recommendations (ie, 2 × 2 contingency tables) were analyzed using Fisher exact tests. Statistical significance was set a priori to P ≤ 0.05. All analyses were performed in RStudio (version 0.99.486).

Results

A total of 108 (37%) ADs completed the survey. Of these, exactly half reported their school had an AT available, but just 10 of the 54 schools reported having an AT available for 40 or more hours per week.

Only 11% (95% CI, 6%-19%) of the schools met all 3 best practice recommendations, while 30% (95% CI, 21%-40%) had implemented 2, 32% (95% CI, 24%-42%) of schools 1, and 27% (95% CI, 19%-36%) of schools had not implemented any. Schools with an AT available were more likely to have implemented the best practice recommendations (χ2 = 10.3, P = 0.016), and the proportion of schools with ATs increased with the number of recommendations adopted (χ2 = 9.3, P = 0.002) (Supplementary Figure 1, available at http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/suppl/10.1177/1941738116686782).

Only 38% (95% CI, 29%-48%) of ADs reported that their school had venue-specific EAPs. AT availability was associated with EAP adoption (P = 0.005). Specifically, 52% (95% CI, 38%-66%) of schools with an AT had venue-specific EAPs for all venues, whereas only 24% (95% CI, 14%-38%) of schools without an AT had them (Supplementary Figure 2).

AEDs were available within 4 minutes at all venues in 56% (95% CI, 47%-66%) of schools, at some venues in 37% (95% CI, 28%-47%) of schools, and there was no AED in 6% of schools (95% CI, 3%-13%). There was a significant association between AT availability at the school and availability of AEDs for early defibrillation at all venues (P = 0.019). Specifically, 69% (95% CI, 54%-80%) of schools with an AT had AEDs available in all venues in contrast to only 44% (95% CI, 31%-59%) of schools without an AT (Supplementary Figure 3). All schools with an AT had at least 1 AED available on campus.

Both CPR and AED training were required for coaches in 31% (95% CI, 22%-40%) of schools. No significant association existed between AT availability and whether a school required coaches to be trained (P = 0.677); 33% (95% CI, 22%-48%) of schools with an AT and 28% (95% CI, 17%-42%) of schools without an AT required coaches to have CPR and AED training (Supplementary Figure 4).

Discussion

Most Oregon high schools were not fully prepared for sports-related emergencies, with just more than 10% implementing all 3 of the best practice recommendations and nearly 30% not implementing any. Although AT services were available at just half of the schools, their presence was associated with increased adoption of best practice recommendations, including venue-specific EAPs and AED availability.

Emergency Action Plan Implementation

Although multiple organizations advocate implementing venue-specific EAPs, only 38% of responding schools had done so. This finding is lower than previous reports of EAP implementation in high schools,9,12,14,17,23,25 most likely because the survey asked specifically about having EAPs for all athletic venues. However, it is greater than a previous report that reported 13% of schools with an EAP had it “visible everywhere.”14

This study found that having an AT available at the high school was associated with EAP implementation. However, nearly half of the schools with an AT had not implemented venue-specific EAPs. It is possible that ADs were unaware of existing EAPs, though awareness is arguably a major part of implementation, and AD and administration review (along with distribution and practice) of EAPs is clearly delineated in the recommendations.1,3 Regardless of explanation, EAP implementation should be emphasized for all high schools.

AED Availability

Life-saving equipment must be readily available if it is to be beneficial. Only 56% of schools in this study met the recommendation for having an AED available for early defibrillation, which is nearly identical to results of a previous study.14 Timely AED availability was associated with AT school presence, with all of the schools with an AT having at least 1 AED on campus. These results suggest ATs may have a role in both the presence and timely availability of AEDs on high school campuses.

Of note, early defibrillation was defined in this study as <4 minutes. This time frame is longer,3 within,4,7 or less than others.8 Ideally, an AED would be immediately available at all venues; however, this goal is unlikely to be met at this time given the myriad of constraints, such as cost and lack of trained personnel.

Availability of Trained Personnel

Multiple organizations recommend that ATs be available for emergency situations.3-5,16 Despite this, only 50% of responding Oregon high schools had an AT available, nearly identical to a recent estimate.18 Many schools either have no AT or do not have ATs at all venues; thus, initial emergency response will likely fall on coaches. Regardless of AT presence, coaches in 85% of schools provided care, similar to previous reports.6,9 This is despite previous reports indicating that coaches lack the knowledge deemed necessary to provide adequate care.2,11,20,22

Because sudden cardiac arrest is the leading nontraumatic cause of death in young athletes, CPR and AED training are vital.13 However, only 31% of the schools reported requiring coach certification in CPR and AED use, nearly identical to a previous study.9 While some coaches may have completed training voluntarily, school policy is more likely than individual choice to achieve universal coach CPR and AED training.

Coach CPR and AED training was not associated with AT presence. One potential explanation is that this recommendation requires at least a school-wide mandate, which ATs do not have the authority to institute.

This study is not without limitations. The survey has not been validated; therefore, it is unknown whether what the ADs reported is what is actually occurring in schools. Hence, it may be beneficial to survey ATs as well as ADs. Nonetheless, an AD’s lack of knowledge would still not be considered best practice and indicates the need for improvements in emergency preparedness. Additionally, future studies should examine whether schools in other states are similar in their sports-related emergency preparedness.

Conclusion

Much work remains to prepare schools and their personnel for sports-related medical emergencies. While most schools have an AED on campus, other areas related to emergency preparedness lag. To maximize effectiveness, all facets of the emergency response must be in place: a plan, trained personnel, and equipment available immediately.

The likelihood of inadequate emergency planning is greater in the absence of an AT. ATs are ideally suited to guide the development and implementation of emergency policies and procedures; schools should use the AT as a resource, and ATs must in turn promote the use of best practices. In schools without an AT, other approaches will be required to improve best practice implementation. Policy changes at multiple levels may be needed to effectively implement change.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

The authors report no potential conflicts of interest in the development and publication of this article.

References

- 1. Andersen JC, Courson RW, Kleiner DM, McLoda TA. National Athletic Trainers’ Association position statement: emergency planning in athletics. J Athl Train. 2002;37:99-104. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Barron MJ, Powell JW, Ewing ME, Nogle SE, Branta CF. First aid and injury prevention knowledge of youth basketball, football, and soccer coaches. Int J Coaching Sci. 2009;3:55-67. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Casa DJ, Almquist J, Anderson SA, et al. The inter-association task force for preventing sudden death in secondary school athletics programs: best-practices recommendations. J Athl Train. 2013;48:546-553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Casa DJ, Guskiewicz KM, Anderson SA, et al. National Athletic Trainers’ Association position statement: preventing sudden death in sports. J Athl Train. 2012;47:96-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Council on Sports Medicine and Fitness. Tackling in youth football. Pediatrics. 2015;136:e1419-e1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cross PS, Karges JR, Adamson AJ, Arnold MR, Meier CM, Hood JE. Assessing the need for knowledge on injury management among high school athletic coaches in South Dakota. S D Med. 2010;63:241-245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Drezner JA, Courson RW, Roberts WO, Mosesso VN, Link MS, Maron BJ. Inter-association task force recommendations on emergency preparedness and management of sudden cardiac arrest in high school and college athletic programs: a consensus statement. J Athl Train. 2007;42:143-158. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Guidelines 2000 for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Part 4: the automated external defibrillator: key link in the chain of survival. The American Heart Association in Collaboration with the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation. Circulation. 2000;102(8 suppl):I60-I76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Harer MW, Yaeger JP. A survey of certification for cardiopulmonary resuscitation in high school athletic coaches. WMJ. 2014;113:144-148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jones E, Vijan S, Fendrick AM, Deshpande S, Cram P. Automated external defibrillator deployment in high schools and senior centers. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2005;9:382-385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kujawa R, Coker CA. An examination of the influence of coaching certification and the presence of an athletic trainer on the extent of sport safety knowledge of coaches. Appl Res Coach Athl Ann. 2000;15:14-23. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lear A, Hoang M-H, Zyzanski SJ. Preventing sudden cardiac death: automated external defibrillators in Ohio high schools. J Athl Train. 2015;50:1054-1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Maron BJ, Doerer JJ, Haas TS, Tierney DM, Mueller FO. Sudden deaths in young competitive athletes: analysis of 1866 deaths in the United States, 1980-2006. Circulation. 2009;119:1085-1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Monroe A, Rosenbaum DA, Davis S. Emergency planning for sudden cardiac events in North Carolina high schools. N C Med J. 2009;70:198-204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. National Federation of State High School Associations Sports Medicine Advisory Committee. Heat acclimization and heat illness prevention position statement. 2015. http://www.nfhs.org/media/1015653/heat-acclimatization-and-heat-illness-prevention-position-statement-2015.pdf. Accessed September 22, 2015.

- 16. National Federation of State High School Associations Sports Medicine Advisory Committee. Recommendations and guidelines for minimizing head impact exposure and concussion risk in football. 2014. http://www.nfhs.org/media/1014884/2014_nfhs_recommendations_and_guidelines_for_minimizing_head_impact_october_2014.pdf. Accessed July 6, 2015.

- 17. Olympia RP, Dixon T, Brady J, Avner JR. Emergency planning in school-based athletics: a national survey of athletic trainers. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2007;23:703-708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pryor RR, Casa DJ, Vandermark LW, et al. Athletic training services in public secondary schools: a benchmark study. J Athl Train. 2015;50:156-162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pryor RR, Huggins RA, Casa DJ. Best practice recommendations for prevention of sudden death in secondary school athletes: an update. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 2014;26:124-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ransone J, Dunn-Bennett LR. Assessment of first-aid knowledge and decision making of high school athletic coaches. J Athl Train. 1999;34:267-271. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rothmier JD, Drezner JA, Harmon KG. Automated external defibrillators in Washington State high schools. Br J Sports Med. 2007;41:301-305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rowe PJ, Miller LK. Treating high school sports injuries—are coaches/trainers competent? J Phys Educ Recreation Dance. 1991;62:49-54. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Toresdahl BG, Harmon KG, Drezner JA. High school automated external defibrillator programs as markers of emergency preparedness for sudden cardiac arrest. J Athl Train. 2013;48:242-247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Travers AH, Rea TD, Bobrow BJ, et al. Part 4: CPR overview: 2010 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2010;122(18 suppl 3):S676-S684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wasilko SM, Lisle DK. Automated external defibrillators and emergency planning for sudden cardiac arrest in Vermont high schools: a rural state’s perspective. Sports Health. 2013;5:548-552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.