Abstract

Background

Despite numerous clinical trials no efficacious medications for methamphetamine (MA) have been identified. Neuroinflammation, which has a role in MA-related reward and neurodegeneration, is a novel MA pharmacotherapy target. Ibudilast inhibits activation of microglia and pro-inflammatory cytokines and has reduced MA self-administration in preclinical research. This study examined whether ibudilast would reduce subjective effects of MA in humans.

Methods

Adult, non-treatment seeking, MA-dependent volunteers (N = 11) received oral placebo, moderate ibudilast (40 mg), and high-dose ibudilast (100 mg) via twice-daily dosing for 7 days each in an inpatient setting. Following infusions of saline, MA 15mg, and MA 30mg participants rated 12 subjective drug effects on a visual analog scale (VAS).

Results

As demonstrated by statistically-significant ibudilast×MA condition interactions (p < .05), ibudilast reduced several MA-related subjective effects including High, Effect (i.e., any drug effect), Good, Stimulated and Like. The ibudilast-related reductions were most pronounced in the MA 30mg infusions, with ibudilast 100 mg significantly reducing Effect (97.5% CI [- 12.54, -2.27]), High (97.5% CI [-12.01, -1.65]), and Good (97.5% CI [-11.20, -0.21]), compared to placebo.

Conclusions

Ibudilast appeared to reduce reward-related subjective effects of MA in this early-stage study, possibly due to altering the processes of neuroinflammation involved in MA reward. Given this novel mechanism of action and the absence of an efficacious medication for MA dependence, ibudilast warrants further study to evaluate its clinical efficacy.

Keywords: methamphetamine, pharmacotherapy, neuroinflammation, ibudilast, subjective reward

1. INTRODUCTION

Methamphetamine (MA) dependence remains an international public health problem with significant medical and psychological consequences (Darke et al., 2008; Dean et al., 2013; Freeman et al., 2011; Ostrow et al., 2009). An efficacious pharmacotherapy could reduce this negative public health impact, but no medications have strong empirical support. Thus, identification of an efficacious pharmacotherapy remains a high priority (Brensilver et al., 2013; Ling et al., 2006; Vocci and Appel, 2007).

Previously tested medications for MA dependence primarily targeted dopamine or other neurotransmitter systems (Brensilver et al., 2013). The neuroimmune system is involved in MA dependence, and may provide a novel target for pharmacological treatment (Coller and Hutchinson, 2012; Hutchinson and Watkins, 2014). In preclinical studies MA increased activation of microglia and astrocytes, and blockade of glial activation attenuated MA-related reward and neurodegeneration (Narita et al., 2006, 2008; Thomas and Kuhn, 2005). Microglia activation temporally precedes striatal dopaminergic neurotoxicity, suggesting a causal role of neuroinflammation in MA-induced neurodegeneration (LaVoie et al., 2004). In humans, abstinent MA users had greater microglia activation than controls (Sekine et al., 2008), and MA users’ peripheral inflammation was strongly correlated with severity of cognitive impairment (Loftis et al., 2011). Altogether these findings support neuroinflammation as a potential target for MA pharmacotherapy.

Ibudilast is a non-selective phosphodiesterase inhibitor that inhibits glial cell activation and production of macrophage migration inhibitory factor and increases expression of neurotrophic factors (Cho et al., 2010; Gibson et al., 2006; Suzumura et al., 1999). Ibudilast has reduced microglia activation and pro-inflammatory cytokine signaling in vitro (Mizuno et al., 2004), and has also reduced MA self-administration and reinstatement of MA use in rodents (Beardsley et al., 2010; Snider et al., 2013). These findings support ibudilast as a potential MA pharmacotherapy in humans. In a sample of MA-dependent adults, we examined whether ibudilast would produce lower subjective ratings of MA than placebo.

2. METHODS

2.1. Subjects

From 110 participants who initiated screening, 15 were randomized but four withdrew prior to completing the study, leaving 11 participants who completed the study and comprise the current sample. Inclusion criteria included age 18 - 55, current MA dependence verified via clinical interview (Spitzer et al., 1995), not seeking treatment for MA dependence, urine-verified recent methamphetamine use, and stable cardiovascular health. Exclusion criteria included current dependence on alcohol or other drugs, seizure disorder, history of head trauma, current use of psychotropic medication, recent suicide attempt, or serious medical/psychiatric illness. UCLA Westwood and Harbor institutional review boards approved the study.

2.2. Study Design

2.2.1. Randomization and Medication

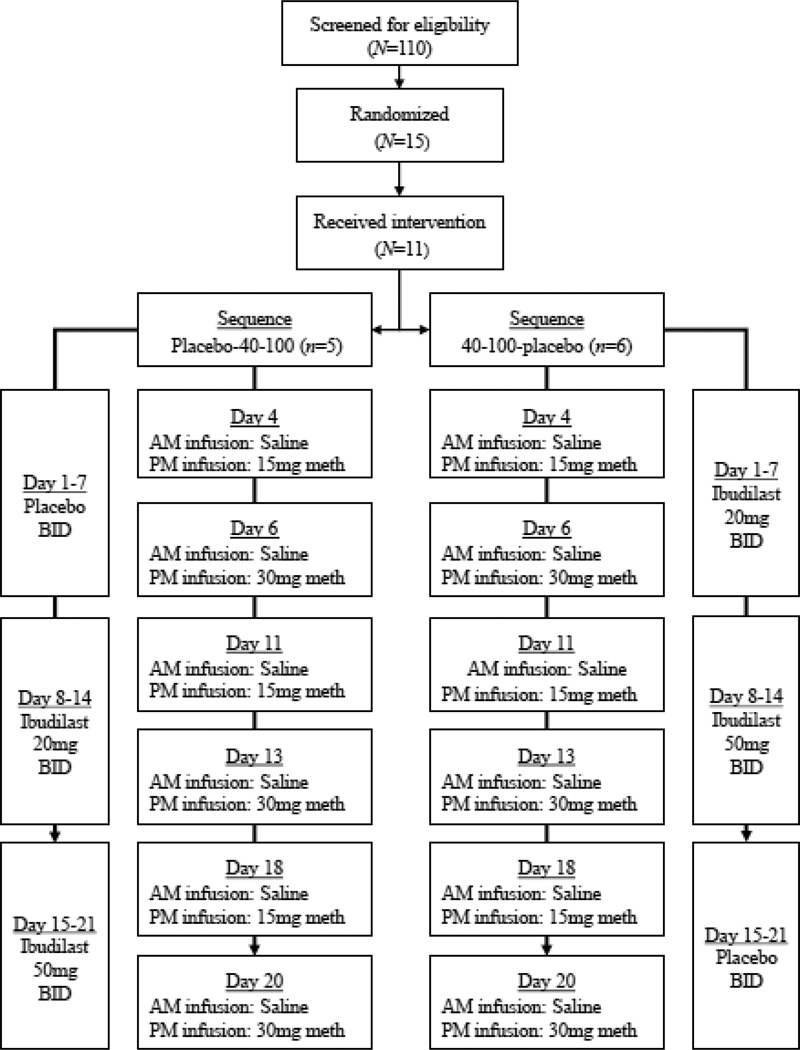

Participants were randomized under a double-blind, within-subjects crossover design (see Figure 1). Placebo, ibudilast 40 mg, and ibudilast 100 mg were administered orally in 7-day blocks with twice-daily dosing, with medication sequence randomized between-subjects as placebo-40 mg-100 mg (n = 5) or 40 mg-100 mg-placebo (n = 6). After the 21-day medication phase and a three-day washout, participants were discharged and completed a two-week follow-up safety check. No serious adverse events occurred and adverse events were limited to common side effects of ibudilast or MA infusions such as insomnia, upset stomach, headaches, or pain at the infusion site (DeYoung et al., under review).

Figure 1.

Schedule of ibudilast dosing and saline/methamphetamine infusions for the two ibudilast sequence conditions, placebo-40 mg-100 mg (n = 5) and 40 mg-100 mg-placebo (n = 6).

2.2.2. Saline and MA infusions

Intravenous (IV) MA infusions allowed optimal control of drug delivery and were delivered over 2 minutes using an automatic pump. Both 15mg and 30mg MA infusions were tested in fixed, ascending order (see Figure 1) to allow optimal testing of safety and dose-dependent drug interactions. Heart rate and blood pressure were monitored continuously during infusion sessions and are reported elsewhere (DeYoung et al., under review). Each 7-day medication block involved two infusions on Day 4 (morning saline, afternoon MA 15mg) and on Day 6 (morning saline, afternoon MA 30mg), with active MA always administered 4 hours after saline.

2.3. Drugs

Blinded 10mg capsules of delayed release ibudilast and placebo were provided by MediciNova, Incorporated. Blister packages for each condition contained the entire course of study medication. Medications were administered twice-daily in five capsules, with 10mg ibudilast or placebo distributed according to study condition.

2.4. Measures

2.4.1. Sample characteristics

Demographic and clinical covariates from the Addiction Severity Index-Lite (Cacciola et al., 2007) included age, sex, race, route of MA use, recent (past-month) frequency of MA use, and recent use of other substances, including alcohol and marijuana, assessed via self-report and urine drug screens.

2.4.2. Subjective drug effects

Participants rated the subjective intensity of 12 drug effects (Morean et al., 2013) on a visual analog scale (VAS) ranging from 0 (Not at all) to 100 (Extremely). At 15 minutes pre-infusion and eight times post-infusion, participants rated “Effect” (Any drug effect?), “High” (How high are you?), “Good” (Any good effects?), “Like” (How much do you like the drug?), “Stimulated” (How stimulated do you feel?), “Want” (How much do you want the drug?), “Use” (How likely would you use the drug?), “Bad” (Any bad effects?), “Nervous” (How nervous do you feel?), “Sad” (How sad do you feel?), “Crave” (How much do you crave the drug?), and “Refuse” (How easily could you refuse the drug?).

2.5. Data analysis

Sequence conditions were compared on baseline covariates using chi-square tests and analysis of variance (ANOVA). Multilevel models were used to analyze all post-infusion VAS ratings controlling for the pre-infusion VAS rating, which is superior to change score models when testing experimental conditions (Vickers and Altman, 2001). Random person-level and day-level intercepts accounted for clustered observations. Models used restricted maximum likelihood estimation which is robust to small sample sizes (Hoyle and Gottfredson, 2014). Covariates included demographics, route of MA use, recent use of MA and other substances, ibudilast sequence, study day, and post-infusion time. Subjective effect models first examined MA condition main effects and potential interactions with time and ibudilast sequence, which were retained if statistically significant (p < .05). Primary models then tested ibudilast X MA condition interactions, with statistically-significant interactions (p < .05) probed by testing the simple ibudilast effect within each MA condition. Planned contrasts compared each ibudilast condition to placebo, using an alpha (.025) and confidence interval (97.5% CI) adjusted for multiple comparisons. Analyses were conducted in Stata 13.0 (StataCorp., 2013).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Demographics and clinical characteristics

The sample (N = 11) was 82% male and 64% white, with mean age of 42.7 years (SD = 7.2). Most of the sample were MA smokers (n = 8, 73%), with a few intravenous MA users (n = 3, 27%). The mean past-month drug use was 17.4 days (SD = 9.6) for methamphetamine, 10.2 (SD = 8.8) for alcohol, and 5.2 days (SD = 7.4) for marijuana. The ibudilast sequence conditions did not differ significantly on sex, Χ2 (1) = 0.92, p = .34, ethnicity, Χ2 (1) = 2.21, p = .14, route of MA use, Χ2 (1) = 1.40, p = .50, alcohol use, F (1, 9) = 1.25, p = .29, or marijuana use, F (1, 9) = .01, p = .95. Participants in the placebo-40-100 condition were significantly younger, F (1, 9) = 15.09, p < .01, and had greater recent MA use, F (1, 9) = 8.83, p < .05, so subsequent models covaried for age and MA use.

3.2. Effects of MA condition, time, and ibudilast sequence on subjective drug effects

Compared to saline infusions, active MA produced prototypical changes in all subjective drug effects, with significantly greater ratings of Effect, High, Good, Like, Stimulated, Want, Bad, Nervous, Sad, and Crave and significantly lower ratings of “Refuse.” Significant MA condition X time interactions for Effect, High, Good, Like, Stimulated, Want and Use indicated MA infusions (as compared to saline infusions) produced greater in-session peaks and greater time-related reductions during the infusion session. For other subjective effects, the time-related changes in VAS ratings were similar following MA and saline infusions, with significant decreases in “Nervous” and “Sad” but no significant time-related changes in other subjective effects. Significant MA condition X ibudilast sequence interactions for Effect, High, Want, Good, Like, Stimulated, Bad, Sad, and Nervous indicated that the 40-100-placebo condition had dampened response to active MA. Subsequent models controlled for these significant main effects and interactions of MA condition.

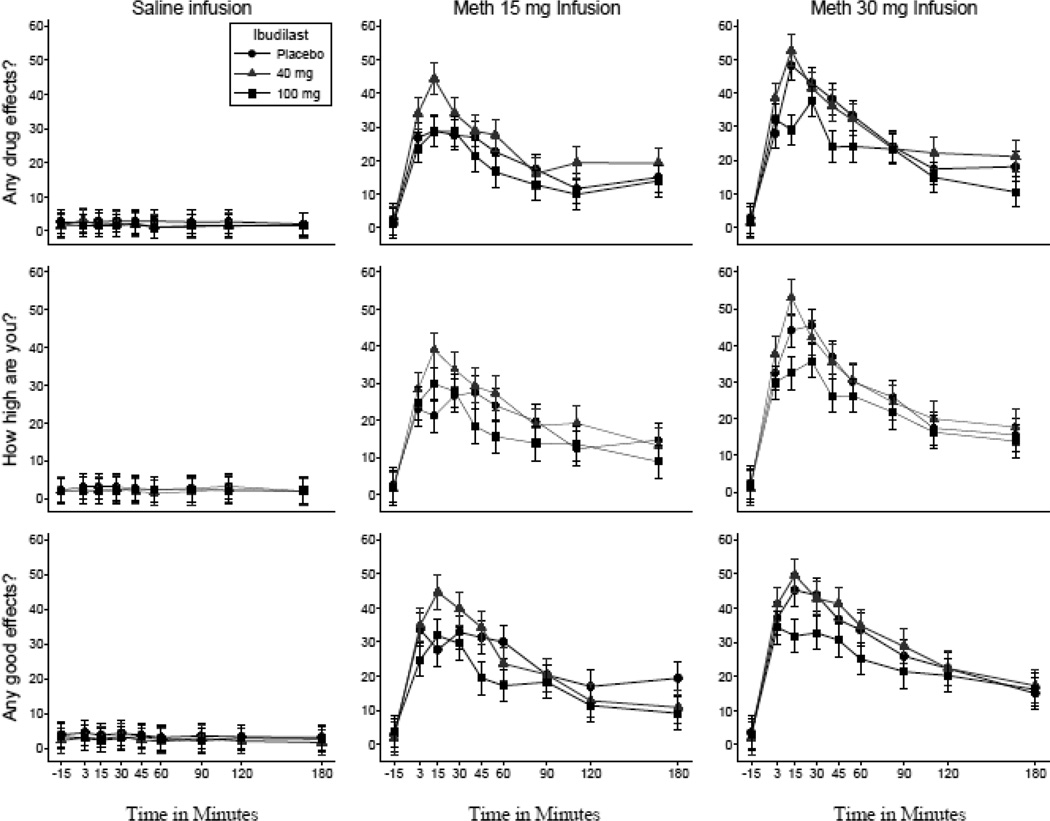

3.3. Interactions of ibudilast X MA condition on subjective drug effects

Ibudilast X MA condition interactions were statistically-significant for “Effect” (Wald Χ2 (4) = 20.76, p < .001), “High” (Wald Χ2 (4) = 12,19, p < .05), “Good” (Wald Χ2 (4) = 14.17, p < .01), “Like” (Wald Χ2 (4) = 12.68, p < .05), “Stimulated” (Wald Χ2 (4) = 9.60, p < .05), and “Use” (Wald Χ2 (4) = 11.15, p < .05), such that MA-related increases in VAS ratings were attenuated by active ibudilast (compared to placebo). Ibudilast simple effects in the MA 30mg condition were statistically significant for “Effect” (Wald Χ2 (2) = 11.70, p < .001), “High” (Wald Χ2 (2) = 9.58, p < .01), and “Good” (Wald Χ2 (2) = 8.07, p < .05). As shown in Figure 2, ibudilast 100 mg produced significantly lower ratings of “Effect” (b = -7.41, z = -3.24, p < .001, 97.5% CI [-12.54, -2.27]), “High” (b = -6.83, z = -3.02, p < .01, 97.5% CI [-12.01, -1.65]), and “Good” (b = -5.70, z = -2.38, p = .02, 97.5% CI [-11.20, -0.21]) compared to placebo. Ibudilast simple effects did not meet adjusted significance for “Like”, “Stimulated”, or “Use”, although planned contrasts were in the expected direction for “Like” (b = -5.80, z = -1.98, p = .047) and “Stimulated” (b = -4.59, z = -2.05, p = .04), with lower ratings in ibudilast 100 mg than placebo.

Figure 2.

Mean visual analogue scale ratings (Range = 0–100) of “Any Effect”, “High”, and “Good” for the 30mg methamphetamine infusions, displayed separately by ibudilast condition. Error bars indicate 95% confidence interval of model-adjusted contrast between each ibudilast dose and placebo.

Ibudilast X MA condition interactions were also statistically-significant for “Nervous” (Wald Χ2 (4) = 11.13, p < .05) and “Bad” (Wald Χ2 (4) = 19.96, p < .001), with statistically- significant simple effects of ibudilast for “Nervous” (Wald Χ2 (2) = 11.70, p < .001) and “Bad” (Wald Χ2 (2) = 6.23, p < .05) in the MA 15mg condition only. Contrast tests indicated ibudilast 40 mg produced greater ratings of “Nervous” than placebo (b = 4.88, z = 2.57, p = .01), while ibudilast 100 mg produced greater ratings of “Bad” than placebo that did not meet adjusted the significance level (b = 3.52, z = 1.93, p = .05). Ibudilast X MA condition interactions for “Want”, “Refuse”, or “Crave” were not statistically significant.

4. DISCUSSION

Using a double-blind, placebo-controlled, within-subjects crossover design, this study examined the effects of ibudilast on subjective MA response in a MA-dependent sample. Ibudilast attenuated several of the prototypical subjective effects of MA, most notably “High”, “Effect”, and “Good”, with reductions in “Stimulated” and “Like” that were less robust. Similar to preclinical research (Snider et al., 2013), the advantage of ibudilast over placebo was limited to the largest dose of ibudilast (100 mg daily). Results supported hypotheses that ibudilast would reduce subjective effects of MA. These findings provide initial evidence that medications targeting neuroinflammatory processes can alter subjective MA response in humans.

For the highest infusion of MA, ibudilast 100 mg reduced ratings of “Any Effect” by 24%, “High” by 22%, and “Good” by 19% from the levels reported during placebo. These proportional reductions are similar to other stimulant medications that had promising results in early-stage testing (De La Garza et al., 2010; Newton et al., 2006; Rush et al., 2011). While subjective effects are putative markers of drug reward (Comer et al., 2008), they have limited predictive validity for MA treatment outcomes; even medications with the most promising early- stage results have not been efficacious in treatment studies (Brensilver et al., 2013). Further research is necessary to determine the clinical efficacy of ibudilast, and a randomized, controlled trial is currently in progress (see clinicaltrials.gov, PI: Heinzerling). Nonetheless, the convergence of our findings with preclinical data (Beardsley et al., 2010; Snider et al., 2013) demonstrates early translational support for ibudilast as a potential treatment for MA dependence, and potentially other drugs of abuse (Bell et al., 2015). These early-stage results are perhaps most encouraging considering ibudilast’s novel purported target of reducing neuroinflammatory processes, such as attenuation of microglial activation and pro-inflammatory cytokine signaling, as well as increasing expression of neurotrophic factors (Beardsley and Hauser, 2014; Bland et al., 2009; Niwa et al., 2007). Future studies that directly measure pro- inflammatory markers could elucidate the precise biological mechanisms that explain our findings.

Strengths of our study include a controlled, four-week, inpatient, crossover design with strong internal validity, but several limitations must also be noted. We used a fixed, ascending order of ibudilast dose and MA infusion to maximize safety, which confounded ibudilast dose and MA condition with time. While our analyses controlled for time and other unanticipated design effects (e.g., ibudilast sequence), time effects and the duration of ibudilast maintenance may still have confounded our findings. In particular, the combination of 100 mg ibudilast and 30mg MA infusion always occurred near the end of ibudilast maintenance. Furthermore, our small sample included mostly male, non-treatment seeking volunteers, which limits immediate generalizability. Finally, our findings with minimal doses of MA to investigate safety interactions may not translate to larger MA doses typically used by MA-dependent adults.

Despite these limitations, this study provides initial evidence that ibudilast can reduce the subjective effects of MA. Given the novel therapeutic target of ibudilast and the absence of an efficacious medication for MA dependence, ibudilast warrants further investigation in a clinical trial as a potential pharmacotherapy for MA dependence.

Highlights.

Ibudilast is a potential pharmacotherapy for methamphetamine (MA) dependence.

Subjective ratings of methamphetamine were completed by MA-dependent adults.

Ibudilast reduced some of the positive ratings of MA, compared to placebo.

Ibudilast warrants further study in a clinical trial for MA dependence treatment.

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Source

Data collection for this study was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) 5R01DA029804. The data analysis, interpretation, and preparation of this manuscript was supported by NIDA grants 5T32 DA026400, and 5R01 DA030577.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributors

Dr. Worley designed the analytic plan, conducted the statistical analyses, and drafted the manuscript. Dr. Shoptaw and Dr. Heinzerling designed the study, oversaw collection of data and preparation of this manuscript, and edited the manuscript. Dr. Roche assisted with design of the analytic plan and drafting of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Shoptaw and Dr. Heinzerling have received clinical research supplies from Pfizer, Inc. and Medicinova, Inc.

REFERENCES

- Beardsley PM, Hauser KF. Glial modulators as potential treatments of psychostimulant abuse. Adv. Pharmacol. 2014;69:1–69. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-420118-7.00001-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beardsley PM, Shelton KL, Hendrick E, Johnson KW. The glial cell modulator and phosphodiesterase inhibitor, AV411 (ibudilast), attenuates prime- and stress-induced methamphetamine relapse. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2010;637:102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell RL, Lopez MF, Cui C, Egli M, Johnson KW, Franklin KM, Becker HC. Ibudilast reduces alcohol drinking in multiple animal models of alcohol dependence. Addict. Biol. 2015;20:38–42. doi: 10.1111/adb.12106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bland ST, Hutchinson MR, Maier SF, Watkins LR, Johnson KW. The glial activation inhibitor AV411 reduces morphine-induced nucleus accumbens dopamine release. Brain. Behav. Immun. 2009;23:492–497. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brensilver M, Heinzerling KG, Shoptaw S. Pharmacotherapy of amphetamine-type stimulant dependence: an update. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2013;32:449–460. doi: 10.1111/dar.12048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacciola JS, Alterman AI, McLellan AT, Lin YT, Lynch KG. Initial evidence for the reliability and validity of a "Lite" version of the Addiction Severity Index. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;87:297–302. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho Y, Crichlow GV, Vermeire JJ, Leng L, Du X, Hodsdon ME, Bucala R, Cappello M, Gross M, Gaeta F, Johnson K, Lolis EJ. Allosteric inhibition of macrophage migration inhibitory factor revealed by ibudilast. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:11313–11318. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002716107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coller JK, Hutchinson MR. Implications of central immune signaling caused by drugs of abuse: mechanisms, mediators and new therapeutic approaches for prediction and treatment of drug dependence. Pharmacol. Ther. 2012;134:219–245. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comer SD, Ashworth JB, Foltin RW, Johanson CE, Zacny JP, Walsh SL. The role of human drug self-administration procedures in the development of medications. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;96:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darke S, Kaye S, McKetin R, Duflou J. Major physical and psychological harms of methamphetamine use. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2008;27:253–262. doi: 10.1080/09595230801923702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De La Garza R, 2nd, Zorick T, London ED, Newton TF. Evaluation of modafinil effects on cardiovascular, subjective, and reinforcing effects of methamphetamine in methamphetamine-dependent volunteers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;106:173–180. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean AC, Groman SM, Morales AM, London ED. An evaluation of the evidence that methamphetamine abuse causes cognitive decline in humans. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38:259–274. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeYoung D, Heinzerling KG, Swanson A, Tsuang J, Furst B, Yi Y, Wu YN, Shoptaw S. Cardiovascular safety of ibudilast treatment with intravenous methamphetamine administration. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0000000000000511. under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman P, Walker BC, Harris DR, Garofalo R, Willard N, Ellen JM Adolescent Trials Network for, H.I.V.A.I.b.T. Methamphetamine use and risk for HIV among young men who have sex with men in 8 US cities. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2011;165:736–740. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson LC, Hastings SF, McPhee I, Clayton RA, Darroch CE, Mackenzie A, Mackenzie FL, Nagasawa M, Stevens PA, Mackenzie SJ. The inhibitory profile of Ibudilast against the human phosphodiesterase enzyme family. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2006;538:39–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.02.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle RH, Gottfredson NC. Sample size considerations in prevention research applications of multilevel modeling and structural equation modeling. Prev. Sci. 2014;16:987–996. doi: 10.1007/s11121-014-0489-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson MR, Watkins LR. Why is neuroimmunopharmacology crucial for the future of addiction research? Neuropharmacology. 2014;76(Pt B):218–227. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaVoie MJ, Card JP, Hastings TG. Microglial activation precedes dopamine terminal pathology in methamphetamine-induced neurotoxicity. Exp. Neurol. 2004;187:47–57. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling W, Rawson R, Shoptaw S, Ling W. Management of methamphetamine abuse and dependence. Curr. Psych. Rep. 2006;8:345–354. doi: 10.1007/s11920-006-0035-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loftis JM, Choi D, Hoffman W, Huckans MS. Methamphetamine causes persistent immune dysregulation: a cross-species, translational report. Neurotox. Res. 2011;20:59–68. doi: 10.1007/s12640-010-9223-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno T, Kurotani T, Komatsu Y, Kawanokuchi J, Kato H, Mitsuma N, Suzumura A. Neuroprotective role of phosphodiesterase inhibitor ibudilast on neuronal cell death induced by activated microglia. Neuropharmacology. 2004;46:404–411. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2003.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morean ME, de Wit H, King AC, Sofuoglu M, Rueger SY, O'Malley SS. The drug effects questionnaire: psychometric support across three drug types. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 2013;227:177–192. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2954-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narita M, Miyatake M, Narita M, Shibasaki M, Shindo K, Nakamura A, Kuzumaki N, Nagumo Y, Suzuki T. Direct evidence of astrocytic modulation in the development of rewarding effects induced by drugs of abuse. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:2476–2488. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narita M, Suzuki M, Kuzumaki N, Miyatake M, Suzuki T. Implication of activated astrocytes in the development of drug dependence: differences between methamphetamine and morphine. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008;1141:96–104. doi: 10.1196/annals.1441.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton TF, Roache JD, De La Garza R, 2nd, Fong T, Wallace CL, Li SH, Elkashef A, Chiang N, Kahn R. Bupropion reduces methamphetamine-induced subjective effects and cue-induced craving. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:1537–1544. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa M, Nitta A, Yamada Y, Nakajima A, Saito K, Seishima M, Shen L, Noda Y, Furukawa S, Nabeshima T. An inducer for glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor and tumor necrosis factor-alpha protects against methamphetamine-induced rewarding effects and sensitization. Biol. Psychiatry. 2007;61:890–901. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrow DG, Plankey MW, Cox C, Li X, Shoptaw S, Jacobson LP, Stall RC. Specific sex drug combinations contribute to the majority of recent HIV seroconversions among MSM in the MACS. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2009;51:349–355. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181a24b20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush CR, Stoops WW, Lile JA, Glaser PE, Hays LR. Subjective and physiological effects of acute intranasal methamphetamine during d-amphetamine maintenance. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 2011;214:665–674. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-2067-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekine Y, Ouchi Y, Sugihara G, Takei N, Yoshikawa E, Nakamura K, Iwata Y, Tsuchiya KJ, Suda S, Suzuki K, Kawai M, Takebayashi K, Yamamoto S, Matsuzaki H, Ueki T, Mori N, Gold MS, Cadet JL. Methamphetamine causes microglial activation in the brains of human abusers. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:5756–5761. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1179-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snider SE, Hendrick ES, Beardsley PM. Glial cell modulators attenuate methamphetamine self-administration in the rat. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2013;701:124–130. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Williams J, Gibbon M, First MB. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. Stata: Release 13. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Suzumura A, Ito A, Yoshikawa M, Sawada M. Ibudilast suppresses TNFalpha production by glial cells functioning mainly as type III phosphodiesterase inhibitor in the CNS. Brain Res. 1999;837:203–212. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01666-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas DM, Kuhn DM. Attenuated microglial activation mediates tolerance to the neurotoxic effects of methamphetamine. J. Neurochem. 2005;92:790–797. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vickers AJ, Altman DG. Statistics notes: analysing controlled trials with baseline and follow up measurements. BMJ. 2001;323:1123–1124. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7321.1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vocci FJ, Appel NM. Approaches to the development of medications for the treatment of methamphetamine dependence. Addiction. 2007;102(Suppl. 1):96–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]