Abstract

Primary cilia are organelles extended from virtually all cells and are required for the proper regulation of a number of canonical developmental pathways. The role in cortical development of proteins important for ciliary form and function is a relatively understudied area. Here we have taken a genetic approach to define the role in forebrain development of three intraflagellar transport proteins known to be important for primary cilia function. We have genetically ablated Kif3a, Ift88, and Ttc21b in a series of specific spatiotemporal domains. The resulting phenotypes allow us to draw several conclusions. First, we conclude that the Ttc21b cortical phenotype is not due to the activity of Ttc21b within the brain itself. Secondly, some of the most striking phenotypes are from ablations in the neural crest cells and the adjacent surface ectoderm indicating that cilia transduce critical tissue—tissue interactions in the developing embryonic head. Finally, we note striking differences in phenotypes from ablations only one embryonic day apart, indicating very discrete spatiotemporal requirements for these three genes in cortical development.

Introduction

Primary cilia are microtubule based extensions of the plasma membrane with distinct proteomes, membrane composition and signaling dynamics. Microtubules nucleate from centrosomes at the base of the growing cilium and a number of proteins regulate transport, both away from the cell body towards the distal tip (anterograde) and back (retrograde). Based on transport paradigms in other organisms, these are collectively referred to as intraflagellar transport (IFT) proteins and complex-B proteins regulate the anterograde transport, while IFT-A complexes regulate retrograde transport. The primary cilium is an organelle that has undergone a renaissance in the field of developmental biology. This renewed interest has been due to an established role of the cilium for the proper regulation of a number of important developmental pathways. These pathways linked to the cilium include Wnt, PDGF, and IGF [1]. However, the most tantalizing connections between the primary cilium and a pathway have been drawn with the Sonic hedgehog (Shh) signaling pathway. Current models suggest that cilia exert influence on signaling pathways through a combination of differential receptor localization and/or transcription factor processing, especially Gli proteins. Some of the initial data came from forward genetic studies where unbiased mutagenesis screens have identified several genes important for primary cilia form and function to regulate Shh signaling [2, 3].

Mutations in ciliary genes cause a class of diseases referred to as ciliopathies which affect many different organ systems and have been shown to frequently present with intellectual disability [4, 5]. More profound central nervous system defects have been seen in animal models of ciliopathies but these are often associated with other syndromic conditions which are lethal in human [6].

Three genes known to be important for primary cilium form and function are tetratricopeptide repeat domain 21b (Ttc21b), kinesin family member 3a (Kif3a) and intraflagellar transport 88 (Ift88). Ttc21b (also known as Thm1 and Ift139) was originally identified in a mouse forward genetic screen for late stage organogenesis defects where the alien allele had pleiotropic effects [7]. The Ttc21baln/aln mutants are perinatal lethal and show increased Shh signaling in multiple tissues, presumably as a result of abnormal processing of Gli proteins which are known to be important for Shh regulation [8]. Further studies showed that abnormal Hedgehog signaling in these mutants contributes to mispatterning of the embryonic forebrain [6] and to polycystic kidneys [9]. The cellular basis for these defects became clearer upon cloning of the mutated gene as Ttc21b which is part if the IFT-A complex required for proper rates of retrograde transport of cargo from the distal tip of the cilium back into the body of the cell (see [10] for a full review of retrograde IFT). Consistent with this model, studies of ciliary trafficking in the Ttc21baln/aln mutants demonstrated a reduction in the rate of retrograde IFT [8]. Kif3a was initially identified as an axonal transport molecule [11] and a null mouse allele revealed a role for ciliogenesis in the embryonic node [12]. Kif3a is one subunit of the heterotrimeric kinesin complex which is responsible for the anterograde transport of the IFT trains along the axoneme from the centrosome to the distal tip of the cilium [13, 14]. In most contexts, mutations in Kif3a are associated with loss or reduction of Shh signaling [3], but in the craniofacial tissues loss of Kif3a leads to an increase in Shh signaling [15]. Ift88 was initially identified in a mouse model of polycystic kidney disease [16, 17] and is also required for proper Shh signaling [3]. IFT88 is a protein within the approximately ten-member “IFT-B core” which forms a large complex linking cargo to the anterograde kinesin motor for trafficking to the distal tip of the cilium (for review, see [18]). Thus, these three genes together represent different, but related, aspect of trafficking within the cilium necessary for proper cilia form and function, and consequently, embryogenesis. Craniofacial and/or CNS defects have been demonstrated from loss of function of Kif3a [15], Ift88, and Ttc21b (our own unpublished observations).

Increasing evidence suggests that not all tissues interpret the loss of primary cilia in the same manner. To begin to refine our understanding of how cilia regulate forebrain development, we utilized conditional alleles of Ttc21b, Kif3a and Ift88 in combination with Cre transgenic alleles to ablate these genes in the presumptive forebrain, the definitive forebrain, the neural crest cells surround the forebrain and in the surface ectoderm. Together this series of ablations has revealed a series of striking spatiotemporal requirements for these genes in development of the forebrain. In combination with similarly dynamic requirements in craniofacial development (Schock et al., this issue), we propose different tissues utilize cilia to modulate developmental signaling in tissue-specific and stage-specific contexts.

Materials and methods

Mouse strains and husbandry

All mouse alleles used in this study have been previously published: Ttc21baln is an ENU-induced null allele [8]; Ttc21btm1a(KOMP)Wtsi-lacZ was used for lacZ expression and was mated with a germline FLP recombinase line to remove the gene trap to create a conditional Ttc21btm1c(KOMP)Wtsi-lacZ (Ttc21bflox) allele [9]; Kif3atm2Gsn (Kif3aflox)[19]; Ift88tm1Bky (Ift88 flox)[20]; FVB/N-Tg(EIIa-cre)C5379Lmgd/J (EIIa-Cre) [21]; B6.129S2-Emx1tm1(cre)Krj/J (Emx1-Cre)[22]; 129(Cg)-Foxg1tm1(cre)Skm/J (Foxg1-Cre)[23]; B6.Cg-Tg(Wnt1-cre)11Rth(Wnt1-Cre) [24]; Tfap2atm1(cre)Moon (Ap2a-Cre) [25]; B6;129S4-Gt(Rosa)26Sortm1Sor/J (R26R)[26]; and B6.129(Cg)-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm4(ACTB-tdTomato,-EGFP)Luo/J (ROSAdTom/EGFP)[27]. Published protocols were used for all genotyping except for the Ttc21baln allele where a custom Taqman assay was employed (Invitrogen; details available upon request). Timed matings were established and noon on the day of mating plug was designated embryonic day (E) 0.5. This study was carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health. Animals were housed at or below IACUC determined densities with AALAC-approved veterinary care and fed Autoclavable Mouse Breeder Diet 5021 (LabDiet, St. Louis, MO). The protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (protocol numbers 1D05052 and IACUC2013-0068). All euthanasia (cervical dislocation followed by thoracotomy) and embryo harvests were performed after isoflurane sedation to minimize animal suffering and discomfort.

Embryo collection & microscopy

Embryos were harvested via Caesarian section and dissected, examined and photographed with a Zeiss Discovery.V8, Axiocam MRc5 and AxioVision software. Brain measurements were done within the Axiovision software suite and tabulated with Excel. Student t-tests were performed to measure significance of forebrain measurements.

Histology & immunohistochemistry

Embryos analysis were fixed with formalin for at least twenty-four hours and processed for paraffin embedding. Sections were cut at a thickness of 14μm and stained with hematoxylin and eosin using standard techniques. The TuJI antibody (SIGMA) was used at 1:500 for 2 hours at room temperature on paraffin sections with citrate buffer antigen retrieval with standard DAB staining. Embryos were stained for lacZ using standard protocols [28].

Results

Multiple Cre recombinase transgenics used to genetically ablate cilia genes

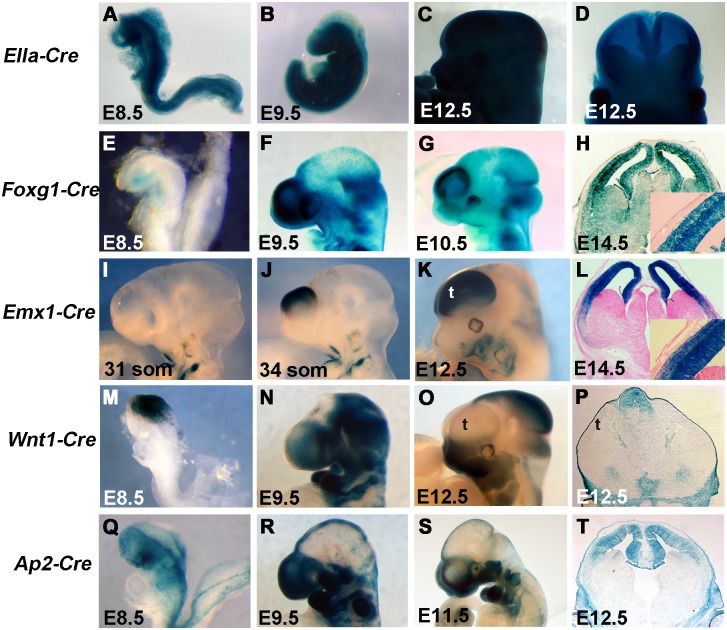

We used a series of Cre-Recombinase expressing mouse transgenic alleles to genetically ablate primary cilia genes in a number of complementary expression patterns [21–25]. The FVB/N-Tg(EIIa-cre)C5379Lmgd/J transgene (called EIIa-Cre here) expresses Cre under the control of the adenovirus EIIa promoter [21]. Expression is somewhat mosaic but begins in the very early embryo and can be used to delete a gene of interest through all or most of the embryo to recapitulate germline null allele phenotypes. Consistent with this expression pattern, we generated EIIa-Cre; R26R embryos in which the pattern of Cre recombination is marked by ß-galactosidase expression from the Cre reporter B6;129S4-Gt(Rosa)26Sortm1Sor/J (R26R) and is seen through the majority of the embryonic tissue we analyzed between embryonic day (E) E8.5—E12.5 (Fig 1A–1D). In order to ablate genes specifically in the developing forebrain, we utilized the 129(Cg)-Foxg1tm1(cre)Skm/J (Foxg1-Cre) and B6.129S2-Emx1tm1(cre)Krj/J (Emx1-Cre) mouse lines. Foxg1-Cre expresses Cre recombinase from the endogenous Foxg1 locus [23] and is one of the earliest known acting Cre’s in the developing mouse forebrain. Consistent with the literature [23], we first noted Cre recombination activity in the developing foregut region at E8.5 (Fig 1E). We observed expression in the early anterior neural ridge and telencephalic vesicle during E8 and strong recombination activity in the telencephalon by E9.5 (Fig 1F) and continuing through E14.5 (Fig 1G and 1H). Consistent with the known recombination pattern of Foxg1-Cre on some genetic backgrounds [23], we did see recombination extending beyond the developing telencephalon in a proportion of our embryos (Fig 1E–1H) but the Cre activity was clearly highly active in the dorsal forebrain. As in previous studies [22], the Emx1-Cre transgenic is active slightly later in cortical development. Emx1-Cre;R26R embryos did not show Cre recombination activity in the telencephalon at E10.25 (Fig 1I) but did indicate robust recombination by E10.5 (Fig 1J). We detected recombination activity throughout the pallium at E12.5 and E14.5 (Fig 1K and 1L). In combination, the Foxg1-Cre and Emx1-Cre allow genetic ablation of “floxed” genes in the forebrain at different stages with the Foxg1-Cre active approximately 36 hours earlier than Emx1-Cre. Consistent with the expression of Foxg1 and Emx1, we see very little or no Cre recombinase activity in the surface ectoderm (see insets in Fig 1H and 1L). In order to address the caveats associated with Foxg1-Cre ectopic recombination, we have incorporated a Cre reporter into our experimental design as described below to identify embryos with desired patterns of Cre activity.

Fig 1. Recombination pattern of Cre transgenics used to ablate cilia genes.

The pattern of Cre-mediated recombination with the R26R-lacZ reporter is shown for all lines used. (A-D) EIIa-Cre is expressed at high levels throughout the embryo with some mosaicism, including the entire nervous system at early organogenesis stages (D). (E-H) Foxg1-Cre is highly expressed in the developing telencephalon from the earliest stages of formation but not in the overlying surface ectoderm (H). (I-L) Emx1-Cre is specific to the dorsal telencephalon with recombination evident between 31 and 34 somite (~E10.5). Note the later onset and more specific recombination as compared to Foxg1-Cre. (M-N) Wnt1-Cre activity is seen in the midbrain and dorsal midline of the neural tube and in the emerging neural crest cells populating the craniofacial tissues (N,O). Note expression is not seen in the telencephalon (P). Ap2-Cre recombination is detected in the dorsal midline and neural crest like Wnt1-Cre, but also in the dorsal telencephalon (T). (t = telencephalon)

We also hypothesize the primary cilia genes we are interested in may affect brain development from non-neural sources such as the neural crest cells and/or surface ectoderm surrounding the developing brain. In order to address these hypotheses, we used the Wnt1-Cre (B6.Cg-Tg(Wnt1-cre)11Rth; [24]), and Ap2-Cre (Tfap2atm1(cre)Moon; [25]) alleles. The Wnt1-Cre is a transgenic expressing Cre via the Wnt1 enhancer [24, 25] and has often been shown to act in very early neural crest cells as they are generated at the dorsal midline in the endogenous Wnt1 expression domain [24, 29–32](Fig 1M). Cre reporter activity after recombination was then continuously detected in the midbrain and NCCs as they migrate from the Wnt1 domain to populate the developing craniofacial tissues (Fig 1N and 1O). Wnt1-Cre activity was not noted in the neural tissue of the developing forebrain but we did note expression in the tissue around the developing forebrain at E12.5 (Fig 1P), consistent with the known lineage of NCC’s contributing to the frontal bone and meninges overlying the telencephalon [30]. The AP2-Cre allele is designed as an IRES-Cre insertion into the transcription factor AP-2, alpha (Tfap2a, formerly Ap2) genomic locus [25]. Regions of Tfap2a expression include the pharyngeal NCC’s and ectoderm. Consistent with this transgenic design, Cre activity was detected as early as E8.5 in the ectoderm (Fig 1Q) and continues to look quite similar to Wnt1-Cre thereafter (Fig 1R, 1S and 1T) with the added neural domain (Fig 1T). The critical difference for our studies is the broader expression of Ap2-Cre as compared to Wnt1-Cre in the early anterior embryo (cf. Fig 1M and 1Q).

Forebrain ablation of Ttc21b does not recapitulate the Ttc21baln phenotype

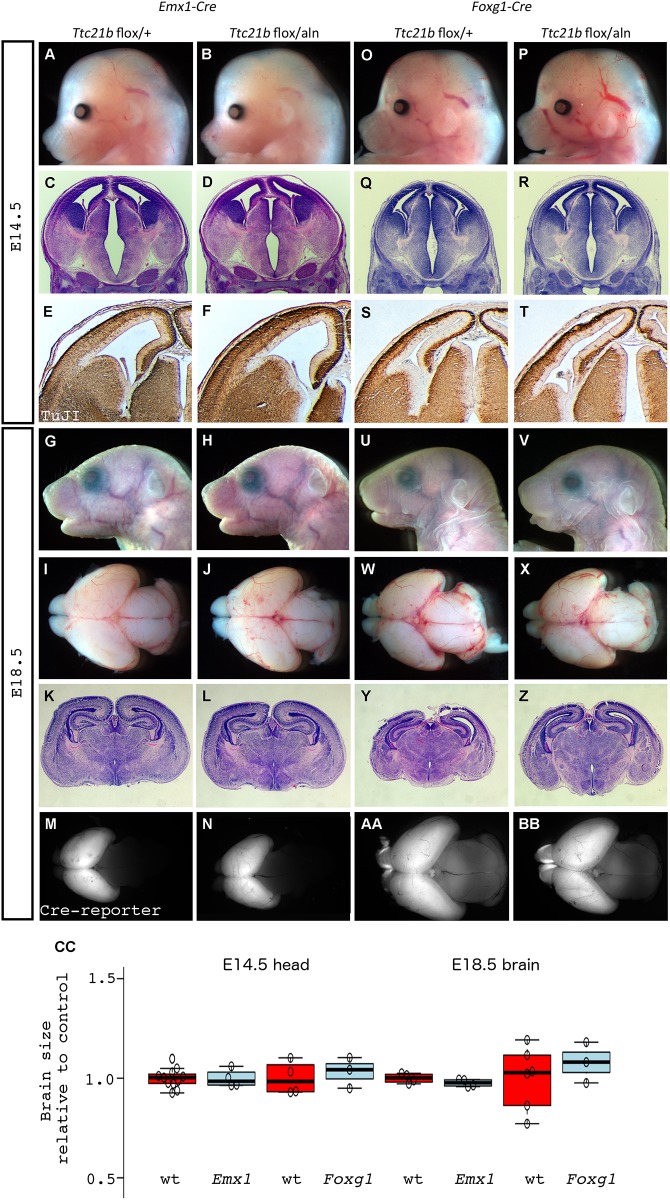

We previously noted that loss of function of Ttc21b in the homozygous Ttc21baln/aln mutant embryos led to profound forebrain defects [6, 8]. Among these were a dramatic reduction in size of the telencephalon and a loss of anterior neural character in favor of an expansion of midbrain fate. We also noted a disorganization of the neuroepithelium within the Ttc21baln/aln cortex. In order to further understand the molecular mechanisms underlying this phenotype, we first sought to use a conditional allele of Ttc21b [9] to ablate Ttc21b in the early telencephalon using Emx1-Cre with the intent of studying the role of Ttc21b in the developing forebrain independent of the earlier embryonic patterning phenotype. Intriguingly, the forebrain microcephaly phenotype seen in the Ttc21baln/aln mouse was not recapitulated in the Emx1-Cre;Ttc21bflox/aln embryos (Fig 2A–2N). In fact, we did not see any obvious morphological differences between control and mutant brain morphology at either E14.5 (Fig 2A–2D) or E18.5 (Fig 2G–2L), either in whole mount or histological analyses. For all of our genotypic classes we quantified head size at E14.5 and brain size at E18.5. Neither of these were affected in the Emx1-Cre;Ttc21bflox/aln embryos with mutant head size being 99.8% of control at E14.5 and 97.6% at E18.5 (Fig 2CC; p = 0.95 and 0.62, respectively). We also performed immunohistochemistry for TuJ1 to highlight differentiated neurons and again saw no difference between mutant and control embryos (Fig 2E and 2F). We additionally observed that Emx1-Cre;Ttc21bflox/aln mutants were capable of surviving into adulthood with no overt behavioral phenotypes or increased morbidity as compared to controls (data not shown). To verify that the Cre recombinase activity occurred as expected, we also incorporated a dual reporter of Cre activity in these crosses. The Cre reporter allele (B6.129(Cg)-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm4(ACTB-tdTomato,-EGFP)Luo/J; hereafter ROSAdTom/EGFP) will produce dTomato protein prior to Cre activity, and EGFP after. As expected, the Emx1-Cre crosses produce embryos with EGFP signal in the forebrain (Fig 2M and 2N) and dTomato signal everywhere else (data not shown).

Fig 2. Deletion of Ttc21b from solely the developing forebrain does not lead to cortical malformation.

(A-N) Emx1-Cre was used to delete a conditional allele of Ttc21b but does not lead to morphological (A,B,G,H,I,J), histological (C,D,K,L) or neural differentiation (immunohistochemistry for TuJI in E,F) phenotypes. Control and Emx1-Cre; Ttc21bflox/aln embryos are shown at E14.5 (A-F) and E18.5 (G-N).. Foxg1-Cre deletions also do not cause cortical phenotypes at E14.5 (O-T) or E18.5 (U-Z). Cre recombination patterns for each genotype are shown with the ROSAdTom/EGFP reporter allele (M,N,AA,BB). All paired images are at the same magnification. (t = telencephalon) (CC) Quantification for brain sizes are normalized to control for each respective experiment. Center lines show the medians; box limits indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles as determined by R software; whiskers extend 1.5 times the interquartile range from the 25th and 75th percentiles, outliers are represented by dots; data points are plotted as open circles. n = 11, 4, 4, 3, 4, 4, 6, 3, respectively. Grey = wt, Red = mut

We reasoned that the Emx1-Cre ablation at E10.5 (Fig 1J) might occur too late in development to recapitulate the embryonic microcephaly of the Ttc21b null allele and took advantage of the earlier Cre activity in the Foxg1-Cre mouse (Fig 1E–1G). At E14.5, we observed no difference in E14.5 Foxg1-Cre;Ttc21bflox/aln embryos as compared to control (Fig 2O–2R, CC; 103% of control brain size, p = 0.16). We did note subtle alterations in the pattern of differentiated neurons with TuJ1 immunohistochemistry (Fig 2S and 2T). Similarly, we noted no obvious differences between Foxg1-Cre;Ttc21bflox/aln embryos and control at E18.5, either in whole mount (Fig 2U–2X; 107% relative brain size, p = .45), or upon histological analysis (Fig 2Y and 2Z). Again, we used the Cre reporter allele to show that the recombination was occurring in the forebrain as expected (Fig 2AA and 2BB). We conclude from these data that ablation of Ttc21b in the forebrain is, surprisingly, insufficient to recapitulate the microcephaly we observed in the Ttc21baln/aln null embryos.

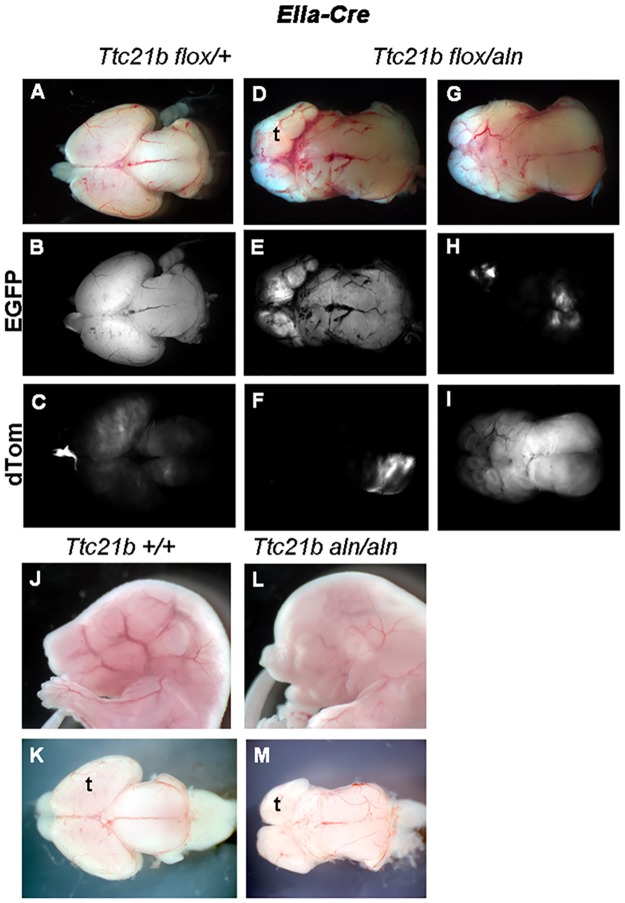

Germline ablation of Ttc21b does recapitulate the Ttc21baln phenotype

Given the surprising results in the Emx1-Cre;Ttc21bflox/aln and Foxg1-Cre;Ttc21bflox/alnembryos, we performed a genetic ablation throughout the embryo to ensure the fidelity of the Ttc21b conditional allele. We used the EIIa-Cre allele to create EIIa-Cre;Ttc21bflox/aln embryos. Both the overall appearance and brain morphology of these mutants were similar to the Ttc21baln/aln phenotype (compare Fig 3D, 3G and 3M). We also noted the expression of EIIa-Cre can be mosaic and utilized the ROSAdTom/EGFP reporter allele to precisely determine the patterns of Cre recombination in the mutant embryos. We recovered EIIa-Cre;Ttc21bflox/aln; ROSAdTom/EGFP embryos which had GFP throughout the forebrain indicating virtually complete recombination (Fig 3E), but also embryos in which the GFP was expressed at relatively low levels in the microcephalic brain (Fig 3H). These findings are consistent with our previous data that Cre recombinase activity within the forebrain is not necessary to generate the microcephalic phenotype of Ttc21baln/aln null embryos. An alternative explanation for the normally sized forebrain in the Emx1-Cre;Ttc21bflox/aln and Foxg1-Cre;Ttc21bflox/aln embryos is a genetic background effect. We have noted a decreased severity of the microcephaly phenotype in Ttc21baln/aln mutants maintained on a C57BL/6J (B6) background as compared to FVB/NJ (FVB; our unpublished observations). To address this possibility, we independently crossed the Ttc21bflox, Emx1-Cre and Foxg1-Cre alleles at least two generations onto both the B6 and FVB backgrounds and generated Emx1-Cre;Ttc21bflox/aln and Foxg1-Cre;Ttc21bflox/aln from each backcross, respectively. No mutants from these crosses on any background have shown different phenotypes.

Fig 3. Deletion of Ttc21b with EIIa-Cre phenocopies homozygous Ttc21baln/aln embryos.

Genetic ablation of Ttc21b with the EIIa-Cre creates microcephalic brains (D,G) which are similar to that seen in homozygous null embryos (L,M). The ROSAdTom/EGFP reporter allele shows the mosaic nature of some EIIa-Cre embryos where EGFP expression (B,E,H) marks recombined tissue and dTom expression (C,F,I) indicates tissue without Cre activity. All paired images are at the same magnification. (t = telencephalon)

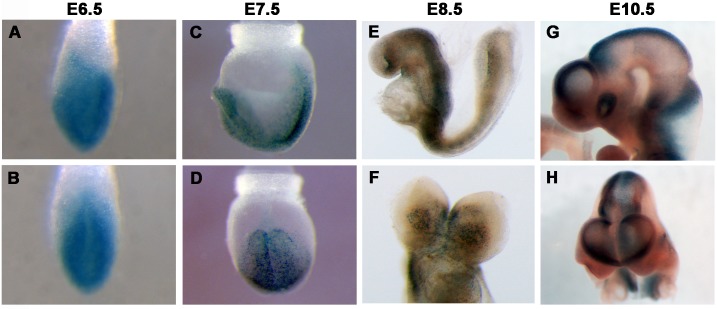

Ttc21b expression is restricted during organogenesis in the mouse

In order to further explore the hypothesis that Ttc21b is required outside the developing forebrain to regulate brain size, we examined expression with the Ttc21btm1a(KOMP)Wtsi-lacZ conditional gene trap allele (Ttc21b-lacZ) [9]. At E6.5 and E7.5, Ttc21b is broadly expressed (Fig 4A–4D). E8.5 expression patterns are similar to our previous RNA in situ hybridization analysis [6] and show broad expression in the embryo with higher levels in the neural tube and somites but not particularly strong expression in the anterior neural tissues (Fig 4E and 4F). Ttc21b expression at E9.5 and E10.5 is again noted in multiple tissues affected in the Ttc21baln/aln mutants [7, 8] such as the limb, eye and dorsal neural tube (Fig 4G and 4H). The expression in the dorsal neural tube and craniofacial tissues as well as the craniofacial phenotypes previously noted in the Ttc21baln/aln mutants [7] suggested the neural crest to be a region requiring Ttc21b activity.

Fig 4. Expression of Ttc21b.

Ttc21blacZ expression at E6.5-E10.5. Frontal views are shown in B,D,F,H.

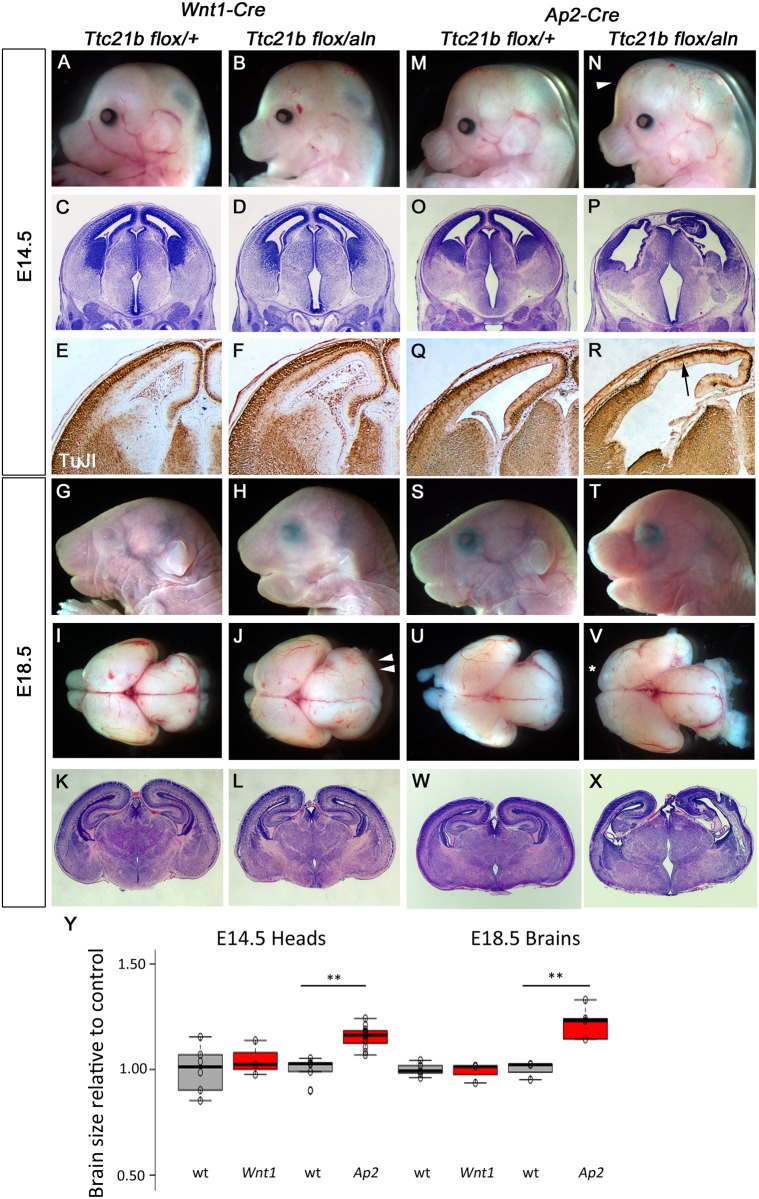

Ttc21b is required in neural crest cells and surface ectoderm to regulate forebrain size

In order to further explore the role of Ttc21b in anterior embryonic development and potentially determine the mechanism leading to the microcephaly in Ttc21baln/aln mutants, we used the Wnt1-Cre and Ap2-Cre alleles to ablate Ttc21b in NCC’s and both NCC’s and surface ectoderm, respectively (Figs 1 and 5). Wnt1-Cre;Ttc21bflox/aln embryos showed no obvious morphological differences in brain development as compared to controls at E14.5 (Fig 5A and 5B, 104% of control, p = 0.55). Histological analysis and TuJI expression were also similar between mutant and control (Fig 5C–5F). However, Wnt1-Cre;Ttc21bflox/aln embryos at E18.5 showed craniofacial phenotypes (Fig 5G and 5H; see Schock et al.,). Microdissection of the brain at this stage indicated a slightly enlarged midbrain in mutants as compared to controls (Fig 5I and 5J). However, histological analysis indicates that the enlargement does not result in any changes in the gross architecture of the mutant forebrain (Fig 5K and 5L; 98.9% of control, p = .708).

Fig 5. Deletion of Ttc21b from neural crest cells and surface ectoderm.

(A-L) Wnt1-Cre mediated deletion of Ttc21b does not lead to morphological (A,B,G,H,I,J), histological (C,D,K,L) or neural differentiation (E,F) phenotypes in the forebrain at E14.5 (A-F) or E18.5 (G-L). The midbrain is enlarged at E18.5 (double arrowheads in J). (M-X) Ap2-Cre; Ttc21bflox/aln embryos at E14.5 and E18.5 have an enlarged forebrain (arrowhead in N, V) with disrupted cortical architecture (P,X) and reduced numbers of differentiated neurons (R). Loss of olfactory bulbs is also noted at E18.5 (asterisk in V). All paired images are at the same magnification. (Y) Quantification for brain sizes. Center lines show the medians; box limits indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles as determined by R software; whiskers extend 1.5 times the interquartile range from the 25th and 75th percentiles, outliers are represented by dots; data points are plotted as open circles. n = 6, 3, 5, 12, 5, 3, 3, 5, respectively. (**: p <0.005).

In contrast to the relatively mild phenotypes in the Wnt1-Cre;Ttc21bflox/aln embryos, ablation of Ttc21b in both the NCCs and surface ectoderm (Fig 1Q–1T) in Ap2-Cre;Ttc21bflox/aln embryos resulted in an obviously enlarged forebrain at E14.5 (Fig 5M and 5N; 115% of control, p = 6.5E-5). Histological analysis highlighted a disruption of normal tissue architecture (Fig 5O and 5P) and TuJI expression analysis showed a reduction in differentiated neurons (Fig 5Q and 5R). Ap2-Cre;Ttc21bflox/aln embryos were also grossly abnormal at E18.5, although not as affected as might be predicted by the E14.5 phenotypes (Fig 5S and 5T). Micro-dissection of the E18.5 brain showed loss of olfactory bulbs, an 23% increase in forebrain size (p = 0.0050), and a grossly normal midbrain (Fig 5U and 5V). Ventriculomegaly of the lateral ventricles was detected along with variable dysmorphology of the hippocampus and cortical plate (Fig 5W and 5X).

Kif3a has a role in forebrain development unique from Ttc21b

A null allele of Ttc21b revealed a role in retrograde trafficking and proper [8]. Our use of the conditional allele described here allowed much more specific conclusions about discrete spatiotemporal requirements for Ttc21b in normal CNS development. Two other genes important for ciliogenesis and anterograde transport within the cilium are Kif3a and Ift88. As conditional alleles exist for each of these, we took a similar approach to determine if there are also discrete spatiotemporal requirements for these primary cilia genes in CNS development.

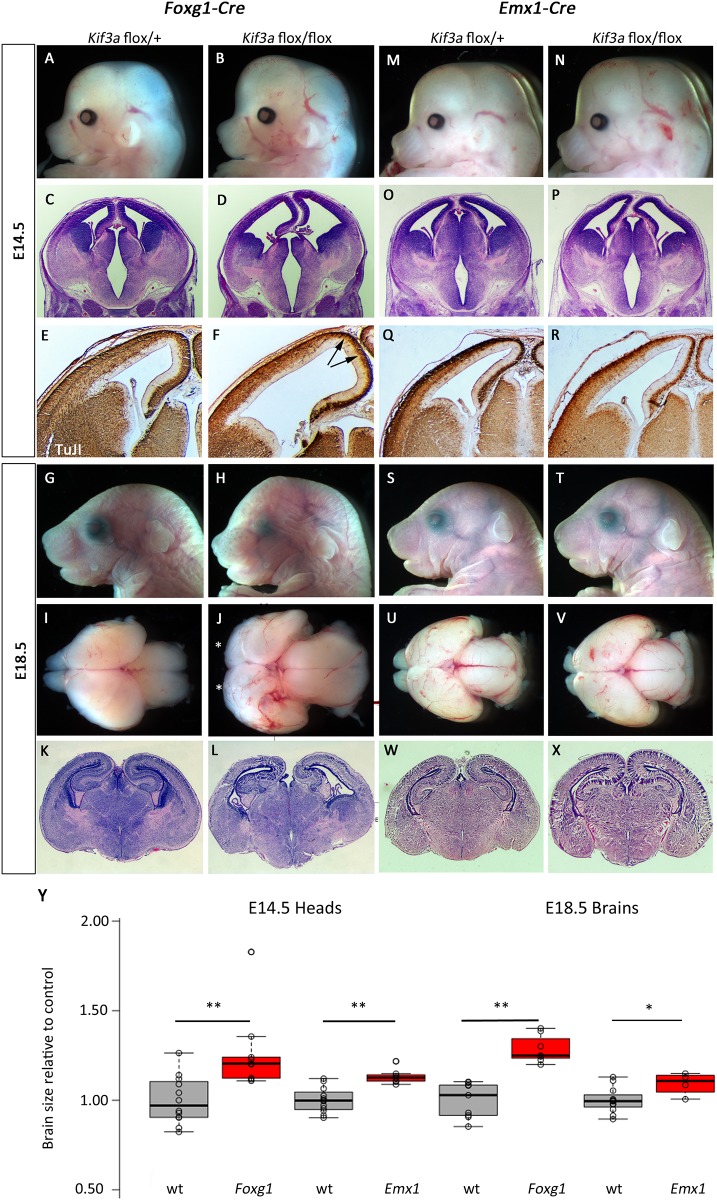

Early forebrain ablation (E9.5) of Kif3a using Foxg1-Cre led to overt developmental defects in the Foxg1-Cre; Kif3aflox/flox mutant embryos. At E14.5, a slightly enlarged cranium was observed (Fig 6A and 6B; 126% size of control, p = 0.0043). Histological analysis revealed ventriculomegaly and a marked reduction in size of the ganglionic eminences (Fig 6C and 6D). TuJ1 expression at E14.5 showed a reduction in the number of differentiated neurons, especially in the extreme dorsal regions of the telencephalon (Fig 6E and 6F). At E18.5, Foxg1-Cre; Kif3aflox/flox mutant embryos were notably dysmorphic with distinctive craniofacial features (Fig 6G and 6H) and microdissection of the brain revealed a significantly enlarged forebrain with loss of olfactory bulbs (Fig 6I and 6J; 128% of control, p = 2.1E-5). Histological analysis confirmed a generally dysmorphic telencephalon and ventriculomegaly (Fig 6K and 6L).

Fig 6. Deletion of Kif3a in early stages of forebrain development leads to increased brain size.

(A-L) Foxg1-Cre was used to delete a conditional allele of Kif3a and the forebrain was enlarged at E14.5 (B) and E18.5 (H,J,). Fewer differentiated neurons are noted in medial regions at E14.5 (D,F, arrows show specific areas of decreased TuJI). Olfactory bulbs are absent at E18.5 in mutants (asterisks in J). (M-X) Similar enlargements are seen with Emx1-Cre ablation but the effects are much less severe. All paired images are at the same magnification. (Y) Quantification for brain sizes. Center lines show the medians; box limits indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles as determined by R software; whiskers extend 1.5 times the interquartile range from the 25th and 75th percentiles, outliers are represented by dots; data points are plotted as open circles. n = 12, 9, 12, 7, 9, 7, 12, 4, respectively. (*:p<0.05, **:p<0.005)

Surprisingly, ablation of Kif3a within the forebrain only slightly later (E10.5) using Emx1-Cre had a very different result. Emx1-Cre; Kif3aflox/flox mutant embryos showed much more subtle enlargement of the forebrain at E14.5 (Fig 6M and 6N; 113% of control, p = 0.0005) and normal histology and differentiation (Fig 6O–6R; forebrain is 109% of control size, p = 0.045). This was also true at E18.5 (Fig 6S–6X). Furthermore, Emx1-Cre;Kif3aflox/flox mice survive postnatally (data not shown).

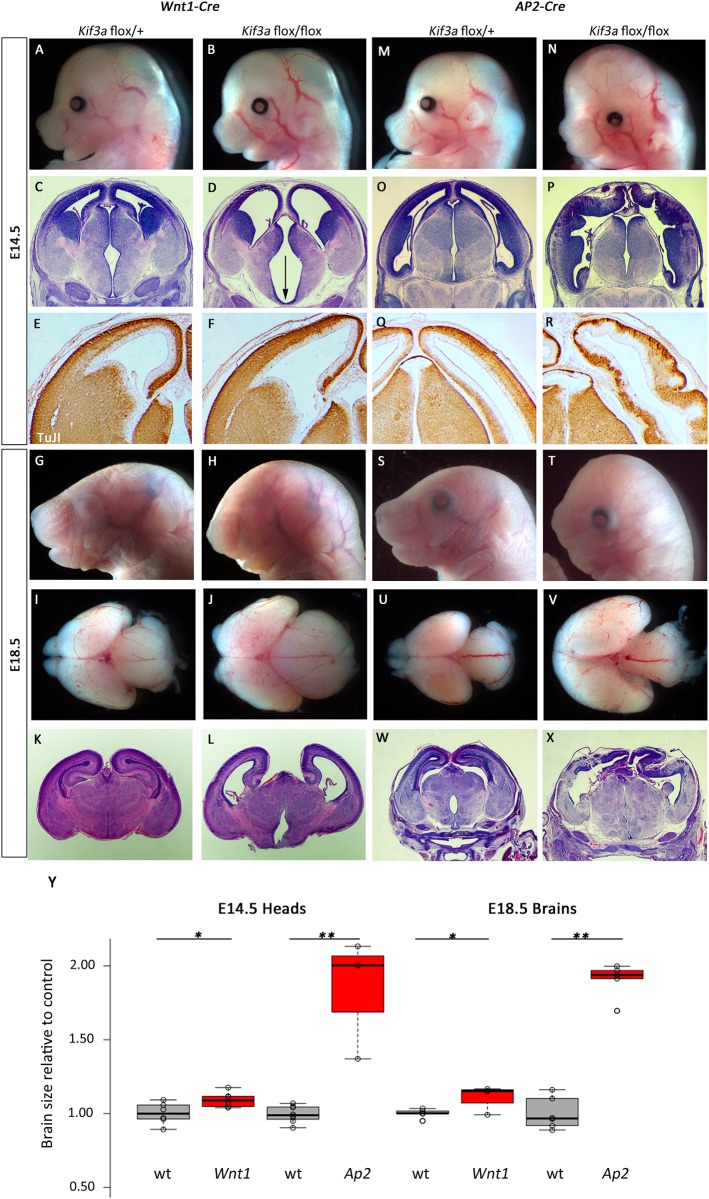

Ablation of Kif3a in the neural crest and midbrain with Wnt1-Cre also led to obvious forebrain phenotypes by E14.5 where the anterior cranium is slightly expanded in Wnt1-Cre; Kif3aflox/flox mutants (Fig 7A and 7B; 109% of control, p = 0.029). Histological analysis revealed significant ventriculomegaly and a widened floor of the third ventricle (Fig 7C and 7D). Neurogenesis did not appear to be disrupted as the pattern of TuJI immunoreactivity appeared similar between mutant and control (Fig 7E and 7F). These abnormalities continued through development and E18.5 mutants had very dysmorphic heads (Fig 7G and 7H) and expanded forebrain (112% of control, p = 0.0229) and midbrain tissue (Fig 7I and 7J). Histological analysis confirmed the mutants had significant ventriculomegaly, reduced hippocampal development and reduced production of mature neurons as evident by a reduced cortical plate (Fig 7K and 7L).

Fig 7. Deletion of Kif3a from neural crest and surface causes cortical malformation.

(A-L) Wnt1-Cre mediated deletion of Kif3a causes morphological (A,B,G,H,I,J), and histological (C,D,K,L) phenotypes in the forebrain at E14.5 (A-F) and E18.5 (G-L). The third ventricle is enlarged at E14.5 (arrow indicates widened base of ventricle in D). (M-X) Ap2-Cre; Kif3aflox/flox embryos at E14.5 and E18.5 have a profoundly enlarged forebrain (N, V) with disrupted cortical architecture (P,R,X). All paired images are at the same magnification. (Y) Quantification for brain sizes. Center lines show the medians; box limits indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles as determined by R software; whiskers extend 1.5 times the interquartile range from the 25th and 75th percentiles, outliers are represented by dots; data points are plotted as open circles. n = 6, 6, 8, 3, 5, 4, 6, 5, respectively. (*:p<0.05, **:p<0.0005)

We observed similar, but more dramatic, deficits in Ap2-Cre; Kif3aflox/flox mutants where the Cre recombination pattern extends beyond the neural crest and also includes the surface ectoderm (Fig 1R–1T). In these mutants, the anterior expansion was much more noticeable at E14.5 than the Wnt1-Cre mediated recombination (Fig 7M and 7N; 184% of control, p = 3.48E-7). Histology and TuJI immunohistochemistry revealed that neurogenesis was profoundly disrupted as there appeared to be a significant expansion of the ventricular zone (indicating hyper-proliferation) in the Ap2-Cre; Kif3aflox/flox mutant telencephalon as compared to controls (Fig 7O–7R). These abnormal phenotypes are even more dramatic at E18.5 (Fig 7S–7X). In addition to the severe shortening of the snout, Ap2-Cre; Kif3aflox/flox mutants lacked olfactory bulbs and had massively expanded forebrains (Fig 7U and 7V; 190% of control, p = 1.45E-4). Histological analysis confirmed ventriculomegaly and disorganized cortical tissues consistent with abnormal patterns of neurogenesis (Fig 7W and 7X).

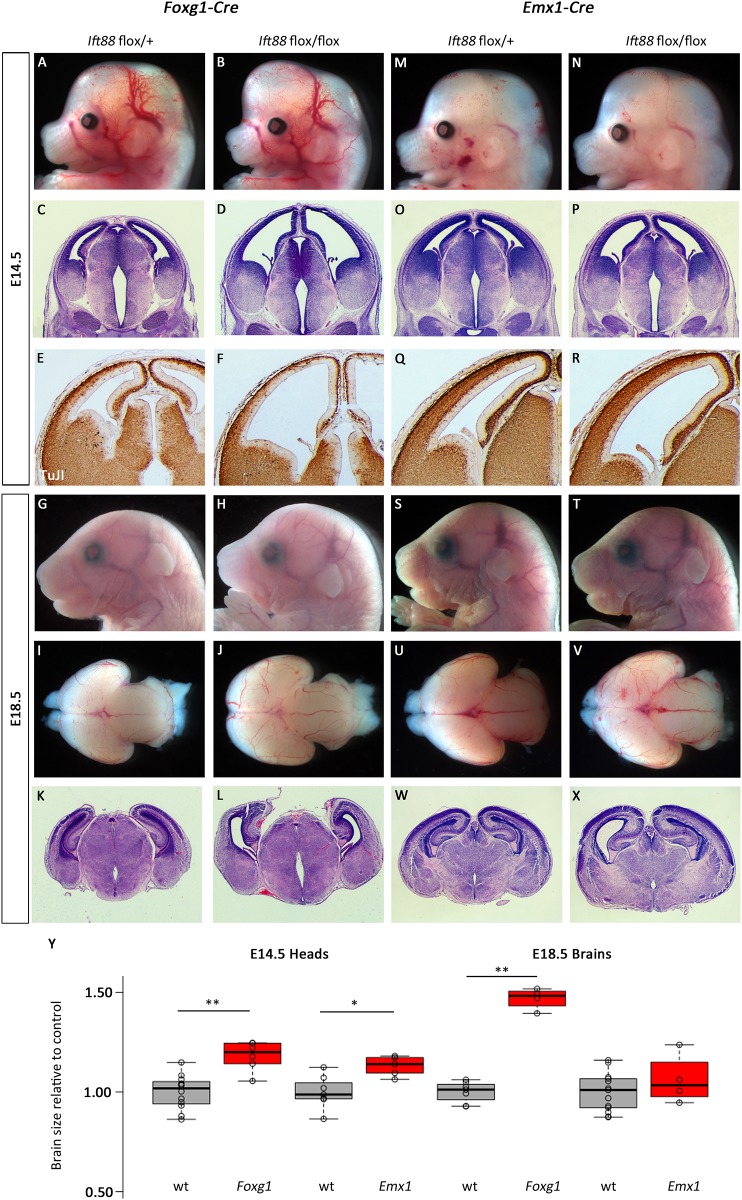

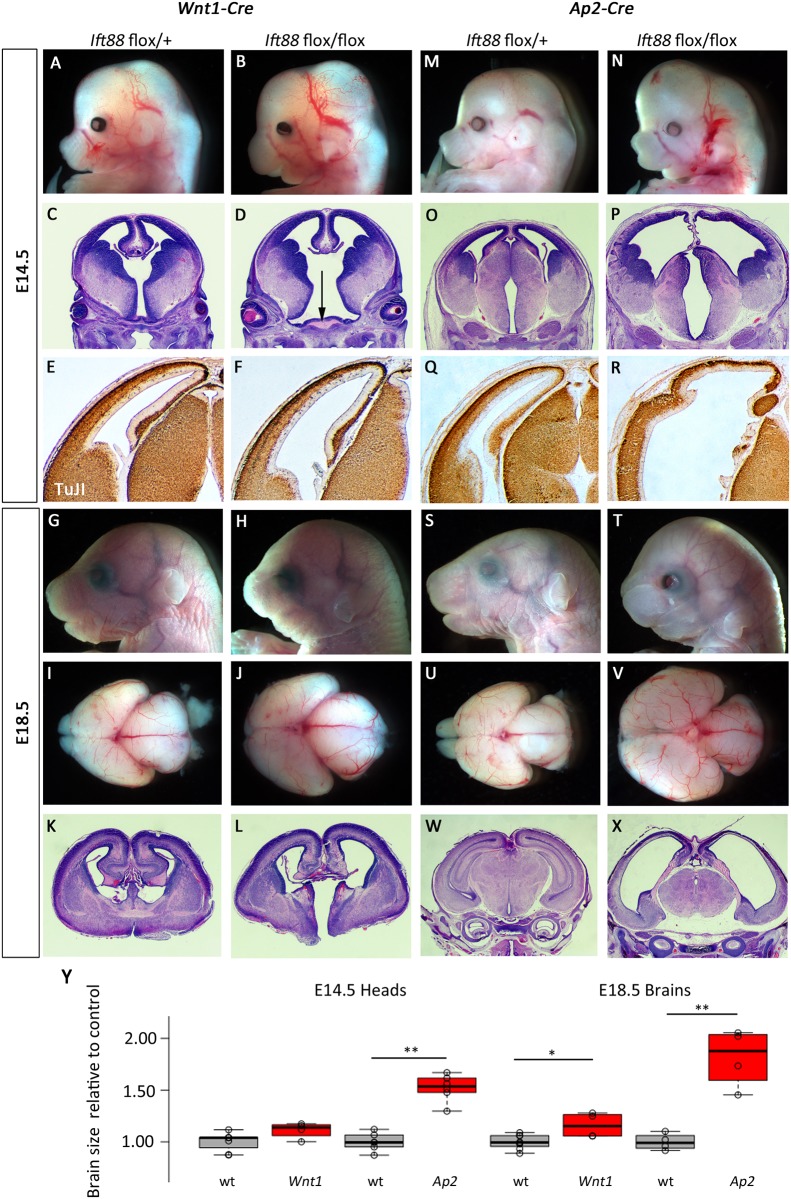

Ift88 conditional ablations reveal different spatiotemporal requirements than either Ttc21b or Kif3a

We next tested the hypothesis that the differences in phenotypes between the Ttc21b and Kif3a ablations are simply a result of the genes different transport functions within the cilium (retrograde and anterograde transport). We used a conditional allele of Ift88 to genetically remove this member of the IFT-B complex which has been previously shown to be required for proper cilia form and function through anterograde transport. Similar to our Kif3a results, early ablation (E9.5) of Ift88 in the mouse forebrain with Foxg1-Cre affects forebrain development. Foxg1-Cre; Ift88flox/flox mutant embryos exhibited a dramatic increase in anterior forebrain tissue (Fig 8A and 8B; 118% of control, p = 0.0004) which was again shown to be the result of ventriculomegaly upon histological analysis (Fig 8C and 8D). However, the reduction in differentiated neurons in the Foxg1-Cre; Ift88flox/flox mutants at E14.5 was more severe than that seen in Foxg1-Cre; Kif3aflox/flox embryos (Fig 8E and 8F). These anterior phenotypes were still notable at E18.5 (Fig 8G and 8H). Microdissection and histological analysis of the brain did reveal a lack of olfactory bulbs and increased forebrain (Fig 8I and 8J; 146% of control, p = 2.08E-7) as well as continued ventriculomegaly affecting the telencephalic and third ventricles and abnormal tissue architecture within the cortical plate (Fig 8K and 8L).

Fig 8. Deletion of Ift88 in early stages of forebrain development leads to increased brain size.

(A-L) Foxg1-Cre was used to delete a conditional allele of Ift88 and the forebrain was enlarged at E14.5 (B) and E18.5 (H,J,). Cortical architecture is disrupted at all stages examined (D,L) and fewer differentiated neurons are seen at E14.5 (F). (M-R) Similar, but less severe, phenotypes are seen with Emx1-Cre ablation at E14.5. (S-X) E18.5 mutants appear phenotypically normal. All paired images are at the same magnification. (Y) Quantification for brain sizes. Center lines show the medians; box limits indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles as determined by R software; whiskers extend 1.5 times the interquartile range from the 25th and 75th percentiles, outliers are represented by dots; data points are plotted as open circles. n = 12, 6, 7, 5, 7, 4, 13, 4, respectively. (*:p = 0.011, **:p<0.005).

Consistent with our other results, genetic ablation of Ift88 only approximately one day later with Emx1-Cre resulted in much less dramatic effects. Emx1-Cre; Ift88flox/flox mutant embryos had more subtle gross morphological defects (Fig 8M and 8N; 113% of control, p = 0.01) and mild ventriculomegaly (Fig 8O and 8P). Neurogenesis and differentiation was largely normal as indicated by the patterns of TuJI immunoreactivity (Fig 8Q and 8R). E18.5 Emx1-Cre; Ift88flox/flox mutant embryos were largely indistinguishable from littermates at E18.5 (Fig 8S and 8T). More detailed analysis of the brain showed only a slight increase in forebrain size (Fig 8U and 8V; 106% of control, p = 0.31) and mild ventriculomegaly with grossly normal cortical tissue architecture. (Fig 8W and 8X).

Genetic ablation of Ift88 with neural crest Cre transgenes again had very dramatic effects on neural development. Wnt1-Cre; Ift88flox/flox mutant embryos were readily recognizable upon dissection (Fig 9A and 9B) had a widening of the ventral midline (Fig 9C and 9D) but we saw no effects on patterns of neural differentiation (Fig 9E and 9F). Wnt1-Cre; Ift88flox/flox mutant embryos at E18.5 had clearly dysmorphic heads (Fig 9G and 9H) and expanded forebrains with severely hypoplastic olfactory bulbs (Fig 9I and 9J; 16% increase in forebrain size,p = 0.013). Histology showed relatively normal patterns of cortical neurogenesis but a dramatic cleft in the ventral brain (Fig 9K and 9L).

Fig 9. Deletion of Ift88 from neural crest and surface causes cortical malformation.

(A-L) Wnt1-Cre mediated deletion of Ift88 causes morphological (A,B,G,H,I,J), and histological (C,D,K,L) phenotypes in the forebrain at E14.5 (A-F) and E18.5 (G-L). The third ventricle is enlarged at E14.5 (arrow indicates widened base of ventricle in D) and cleft at E18.5 (L). (M-X) Ap2-Cre; Ift88flox/flox embryos at E14.5 and E18.5 have a profoundly enlarged forebrain (N, V) with disrupted cortical architecture (P,R,X). All paired images are at the same magnification. (Y) Quantification for brain sizes. Center lines show the medians; box limits indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles as determined by R software; whiskers extend 1.5 times the interquartile range from the 25th and 75th percentiles, outliers are represented by dots; data points are plotted as open circles. n = 7, 4, 6, 6, 8, 4, 4, 4, respectively. (*:p = 0.013, **:p<0.002)

Consistent with the expanded domain of Cre activity in the surface ectoderm, Ap2-Cre; Ift88flox/flox mutant embryos had more dramatic phenotypes at all stages examined. At E14.5, mutants had a dramatically enlarged forebrain (Fig 9M and 9N; 152% of control, p = 1.99E-5). Histological and immunohistochemical analyses indicated ventriculomegaly throughout the first three ventricles and disrupted patterns of neurogenesis in the cortical plate (Fig 9O–9R). E18.5 Ap2-Cre; Ift88flox/flox mutant embryos were easily identified from littermates (Fig 9S and 9T) with an 81% increase in forebrain size (p = 0.001) with significant ventriculomegaly and loss of olfactory bulbs (Fig 9U and 9V) and the most significant loss of cortical tissue of any genotype examined in this study (Fig 9W and 9X).

Taken together, these results show that discrete ablations of three proteins with well-established roles in primary cilia form and function result in very different anterior neural phenotypes. Even with two genes thought to largely function similarly in anterograde transport, notable differences were seen between Kif3a and Ift88 mutants. The details of these phenotypes are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

| E14.5 | E18.5 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forebrain size | Lateral Ventricles | Cortical Morphology | Neuronal Differentiation | Basal Ganglia | Forebrain size | Lateral Ventricles | Cortical Morphology | Olfactory Bulbs | Hippocampus | Midbrain | ||

| Ttc21b | Foxg1 | No Δ | No Δ | No Δ | No Δ | No Δ* | No Δ | No Δ | No Δ | No Δ | No Δ | No Δ |

| Emx1 | No Δ | No Δ | No Δ | No Δ | No Δ | No Δ | No Δ | No Δ | No Δ | No Δ | No Δ | |

| Wnt1 | No Δ | No Δ | No Δ | No Δ | No Δ | No Δ | No Δ | No Δ | Hypo-plastic & laterally displaced | No Δ | Increase | |

| Ap2 a | Large increase | Increase | Dysmorphic | Reduced | Reduced | Large increase | Increased | Dysmorphic | Absent | Dysmorphic | No Δ | |

| Kif3a | Foxg1 | Small increase | Increase | No Δ | Slight reduction | Slight reduction | Large increase | Increased | No Δ | Absent | Dysmorphic | No Δ |

| Emx1 | Small increase | Small increase | No Δ | No Δ | No Δ | Small increase | No Δ | No Δ | No Δ | No Δ | No Δ | |

| Wnt1 | Small increase | Increase | Slight disruption | No Δ | No Δ | Small increase | Increased | Slight disruption | Hypo-plastic & laterally displaced | Dysmorphic | Increase | |

| Ap2 a | Large increase | Large Increase | Dysmorphic | Reduced | Dysmorphic | Large increase | Increased | Dysmorphic | Absent | Dysmorphic | No Δ | |

| Ift88 | Foxg1 | Small increase | Increase | No Δ | Slight reduction | Slight reduction | Large increase | No Δ | Slight disruption | Absent | Dysmorphic | No Δ |

| Emx1 | Small increase | Small increase | No Δ | No Δ | No Δ | No Δ | No Δ | No Δ | No Δ | No Δ | No Δ | |

| Wnt1 | No Δ | Increase | No Δ | No Δ | No Δ | Small increase | No Δ | No Δ | Hypo-plastic | Dysmorphic | Increase | |

| Ap2a | Large increase | Large Increase | Dysmorphic | Reduced | Reduced | Large increase | Large increase | Dysmorphic | Absent | Absent? | No Δ | |

Discussion

This study demonstrates unique spatiotemporal requirements in forebrain development for three genes necessary for normal form and function of the primary cilium: Ttc21b, Kif3a and Ift88. We used four different Cre transgenic alleles to ablate each of these genes across distinct domains within the forebrain. The wide ranging effects of the ablations revealed critical roles for these proteins with interesting differences revealed by both developmental and tissue-specific locations of Cre activity. Forebrain expansion, cortical malformations, impaired olfactory bulb development, and ventriculomegaly were among the many variably observed defects. In addition, our studies revealed that the microcephaly phenotype in homozygous Ttc21baln/aln mutants is likely due to events prior to corticogenesis and the production of defined neural progenitor cells. Taken together, our results clearly show the primary cilia are not reiteratively produced uniformly across the embryos transducing canonical pathways in identical ways. Rather, these seem to be more strategically employed to regulate signaling during organogenesis.

Comparison to previous neural phenotypes

Our work complements and extends prior studies on the role of these gene in cortical development. First, the mechanism of the neural phenotypes revealed by loss of Ttc21b is not fully understood. Our study demonstrated that neither ablation of Ttc21b from the forebrain at E9.5 or E10.5 phenocopied the microcephaly observed in Ttc21baln/aln homozygous mutants. Interestingly, ablation of Ttc21b in the brain and surrounding domains (NCCs and surface ectoderm) as early as E8.5 with the Ap2-Cre served only to increase brain size (Fig 5). The mosaicism of the EIIa-Cre germline ablation provided further evidence that loss of Ttc21b in the brain is not responsible for the microcephaly phenotype (Fig 3). Together, these findings suggest a role for Ttc21b in brain patterning and growth prior to organogenesis stages. Supporting this hypothesis are the findings of early widespread expression of Ttc21b, suggesting the critical role might be during the neural plate stage of development.

A previous study showed ablation of Kif3a using a GFAP-Cre resulted in aberrant Gli activity and cortical overgrowth [33], but the specific transgene used has been shown to be expressed throughout the early embryo which precludes any conclusions about specific lineages and/or spatiotemporal requirements for Kif3a beyond gastrulation [34]. A separate experiment using a GFAP-Cre transgene that initiates recombination around E13.5 [35] did not result in any appreciable differences in forebrain size or morphology [36]. The experiments we present are based on Cre recombinase activity at stages between the GFAP-Cre domains of these earlier studies. Also, similar to our work, an Emx1-Cre; Ift88 ablation did not result in significant changes in brain size [37] and homozygous mice for a hypomorphic allele of Ift88 (Ift88cbs/cbs) have strong similarities to Ttc21baln/aln mutants [38]. The other embryonic requirements for Ift88 presented herein have not been demonstrated. Interestingly, Arl13b is required for proper axoneme structure and Shh signal transduction within the primary cilium [39] but loss of Arl13b within the cortical epithelium had dramatic effects on the polarized radial progenitor scaffold unlike the phenotypes we observe [40]. In a similar experimental paradigm to what we show here, Arl13b deletion after radial progenitors were established had little effect on cortical morphology [40]. Together, these findings also suggest a role for cortical patterning by Ttc21b, Kif3a, and Ift88 outside the cortex itself.

Phenotypes caused by loss of cilia in forebrain tissues suggest involvement of Hh and Wnt signaling activity

Patterning of the neural plate is a crucial early step in proper brain development. The embryonic anterior neural plate (ANP) generates the forebrain and its exposure to, and protection from, various patterning molecules are decisive in this process [41, 42]. One critical signaling pathway which must be regulated in the ANP is canonical Wnt signaling. The Wnt pathway is active throughout the posterior embryo and a rostral expansion of Wnt results in a caudalizing of the anterior embryo including the head and brain [43]. Primary cilia have been previously implicated in modulating Wnt signaling [44]. In Ttc21baln/aln fibroblasts, specifically, increased activation of the Wnt pathway has been shown to occur in the presence of ligand as compared to controls [9]. Together with this previous data, our study suggests that excessive Wnt activity in the early Ttc21baln/aln embryo may be a major contributor to the microcephaly.

The role of primary cilia in transducing another crucial developmental pathway, Shh signaling, has been well established [1, 45]. The Shh pathway has been shown to be upregulated in aln embryos later than the neural pate stage, but has not yet been explored at this stage [6]. Shh is active at the neural plate stage, but remains restricted to the axial midline [46]. Interestingly, this domain contains an important signaling center for ANP development, the axial mesendoderm (AME). The AME is a source of multiple signals which serve to induce the anterior forebrain and protect it from caudalizing influences, including Wnt signaling [41, 46]. Shh signaling has been shown to affect AME signals, offering another potential method by which the aln mutation may be disrupting forebrain development [47, 48]. Increased Shh signaling in the cortex does result in progenitor expansion and cortical folding in a manner somewhat similar to the Ap2-Cre;Ttc21bflox/aln phenotype [49].

With multiple AME signals functioning as Wnt inhibitors, an indirect regulation of the Wnt pathway via a primary disruption in Shh signaling is a possibility. Together, the study of both Shh and Wnt pathways in early developing Ttc21baln/aln mutants represent interesting future areas of research into novel mechanisms of microcephaly.

Similar to Ttc21b, both Kif3a and Ift88 are known to be critical for proper Shh signaling. Unlike the upregulation of the Shh pathway seen in Ttc21baln/aln mutants, both Kif3a and Ift88 mutants have been observed to have reduced Shh pathway activity [3],[1]. However, in some specific tissues, loss of Kif3a and Ift88 can cause domain specific upregulation of the Shh pathway, which complicates any extrapolation of the data into other potential interpretations [15, 50]. Indeed, our work would further suggest tissue-specific responses of the Shh pathway to loss of ciliary proteins. In the Kif3a and Ift88 ablations using Ap2-Cre and Wnt1-Cre, we observed an expansion of the ventral midline and third ventricle of the brain, consistent with an increase in Shh signaling. This midline hyperplasia is not observed in the Ap2-Cre;Ttc21bflox/aln and Wnt1-Cre; Ttc21bflox/aln embryos, despite the generalized association between Ttc21b and increased Shh pathway activity.

Additionally, we observed a mild dorsalization of Kif3a and Ift88 using Foxg1-Cre along with the loss of the ventral basal ganglia, indicative of disrupted Shh pathway in the forebrain. In the dorsal forebrain the Shh pathway is controlled primarily by Gli3 expression, rather than by the Shh ligand itself, and low Shh activity is consistent with dorsal fates. One potential explanation for the increased dorsal telencephalon in these Foxg1-Cre; Kif3a/Ift88 mutants is an increase in the domain of Gli3 repressor activity. Canonically, Gli3 functions as a repressor of downstream Shh pathway genes in the absence of Shh [45]. All three ciliary proteins described in our study have been shown to affect Gli3 processing [8, 33, 51]. Therefore, any disruptions of the Shh pathway may be a result of improper transduction in the presence of Shh signal, failure to properly process Gli3 in regions of low Shh activity, or likely a combination of both. Shh and Gli3 play a number of important roles in the development of the forebrain and central to these processes lies the primary cilium. We have shown the wide-ranging outcomes of these signals which result from differentially impairing cilia based on time, location, and composition.

This study also provides insight into differences between anterograde (Kif3a, Ift88) and retrograde (Ttc21b) trafficking within the cilium. Ablating Ttc21b has an almost universally less severe impact on brain development than the ablations of the anterograde transport genes. This is not surprising in that cilia, although shortened and impaired, are still produced in Ttc21b mutants, while cilia are not produced, or are severely disrupted in either anterograde mutation [8, 36, 52, 53]. Differences in head and brain size are noticed between the Kif3a and Ift88 in the various genetic ablations as are forebrain structural defects. In each case however, Kif3a ablation is observed to have a more severe phenotype than loss of Ift88. This too may be explained by differential effects on ciliary formation. In Kif3a perturbations, the basal body of the cilium attaches to the cell surface but no microtubules are projected while severely truncated microtubules project from a basal body no further than the transition zone in Ift88 mutants [36, 52, 53]. The distal tip of the cilium is known to be crucial for the Shh pathway regulatory role of primary cilia and its absence in these anterograde mutations may explain why both suffer similar Shh signaling disruptions [54]. The ciliary membrane is increasingly being shown to play a unique and important signaling role. The increased area of potential ciliary membrane, which results from the slight projection of Ift88 conditional mutants, may preserve an important function missing in Kif3a mutants, explaining the increased severity of our Kif3a ablations. Future studies on the mechanistic roots of the phenotypes we show here are likely to further enhance our understanding of the role for primary cilia proteins in forebrain development.

Severe defects in both the morphology and neuronal differentiation of these mutants display just how crucial each protein is for proper forebrain development and the importance of the domain and timing of loss. It is known, but underappreciated, that ciliary genes are not all ubiquitously expressed (e.g., [6]). The differences we see here between different genetic ablations highlight the idea that primary cilia may be populated by different proteins in different tissues. This would further demonstrate the primary cilium is not a static organelle repeatedly employed by the embryo to relay information in a standard way. By comparing the different ablations, we can begin to parse out the temporal or regional effects that cause the cortical malformation. By comparing the recombination of Ap2-Cre to Wnt1-Cre, we can eliminate the NCCs as a responsible domain as these phenotypes are not seen in Wnt1-Cre- ablations. This leaves Ap2-Cre activity within the ectoderm (both surface and neuroectoderm) as the responsible domain(s) for the phenotype. Two differences remain between the Ap2a-Cre and Foxg1-Cre ablations: loss within the surface ectoderm and an earlier ablation (by about a day) within the prospective forebrain tissue. We attempted to address the surface ectoderm specifically in our experiments by using the Cre-ectoderm driver, as used in Schock et al., (accompanying manuscript). However, the recombination pattern was quite variable in our hands precluding an effective experiment to address this hypothesis. An alternative route to this answer is an ablation specific to the prospective forebrain at E8.5. Taken together, our experiments clearly show that ciliary protein signaling is crucial for forebrain development in multiple specific spatiotemporal domains of the early embryo. We further demonstrate that ablating similarly acting genes within the cilia can result in strikingly disparate phenotypes from each other and from different ablation time points, suggesting that parallels can only be loosely drawn from experiments in other developmental settings.

We are largely interpreting our results based on a model in which the predominant function of these genes is within the primary cilium. An alternative, or perhaps complementary, model would allow for a role for these proteins outside the primary cilium. Although these ciliary roles are the best established for Ttc21b, Ift88 and Kif3a in embryonic development, the literature clearly indicates we should consider non-ciliary roles as well. The immunocytochemistry analysis of TTC21B localization does clearly show protein is not restricted to tubulin-positive primary cilia [8]. The heterotrimeric kinesin motor is known to play a role in transport along axons, opsin transport in photoreceptors, transporting virus within the cell, and transport of molecules required for cell-cell adhesion (among other functions, see [14, 55] for a full discussion). This represents an area of future investigation for our labs as well as many others. There are multiple mechanisms by which these non-ciliary functions could alter forebrain development in ways such as we demonstrate here.

Acknowledgments

Mouse strains were generously donated by B. Yoder (U Alabama, Ift88) and J. Reiter (UCSF, Kif3a).

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper.

Funding Statement

Support for this work comes from the Cincinnati Children’s Research Foundation (R.W.S., S.A.B.), a March of Dimes Foundation Basil O'Connor Starter Scholar Research Award (Grant No. 5-FY13-194 to R.W.S.) and the NIH (R01DE023804 to S.A.B., and R01NS085023, R01GM112744 to R.W.S.). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Goetz SC, Anderson KV. The primary cilium: a signalling centre during vertebrate development. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11(5):331–44. 10.1038/nrg2774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huangfu D, Anderson KV. Cilia and Hedgehog responsiveness in the mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(32):11325–30. 10.1073/pnas.0505328102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huangfu D, Liu A, Rakeman AS, Murcia NS, Niswander L, Anderson KV. Hedgehog signalling in the mouse requires intraflagellar transport proteins. Nature. 2003;426(6962):83–7. 10.1038/nature02061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guemez-Gamboa A, Coufal NG, Gleeson JG. Primary cilia in the developing and mature brain. Neuron. 2014;82(3):511–21. 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.04.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Valente EM, Rosti RO, Gibbs E, Gleeson JG. Primary cilia in neurodevelopmental disorders. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014;10(1):27–36. 10.1038/nrneurol.2013.247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stottmann RW, Tran PV, Turbe-Doan A, Beier DR. Ttc21b is required to restrict sonic hedgehog activity in the developing mouse forebrain. Dev Biol. 2009;335(1):166–78. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.08.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herron BJ, Lu W, Rao C, Liu S, Peters H, Bronson RT, et al. Efficient generation and mapping of recessive developmental mutations using ENU mutagenesis. Nat Genet. 2002;30(2):185–9. 10.1038/ng812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tran PV, Haycraft CJ, Besschetnova TY, Turbe-Doan A, Stottmann RW, Herron BJ, et al. THM1 negatively modulates mouse sonic hedgehog signal transduction and affects retrograde intraflagellar transport in cilia. Nat Genet. 2008;40(4):403–10. 10.1038/ng.105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tran PV, Talbott GC, Turbe-Doan A, Jacobs DT, Schonfeld MP, Silva LM, et al. Downregulating hedgehog signaling reduces renal cystogenic potential of mouse models. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25(10):2201–12. 10.1681/ASN.2013070735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hou Y, Witman GB. Dynein and intraflagellar transport. Exp Cell Res. 2015;334(1):26–34. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2015.02.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kondo S, Sato-Yoshitake R, Noda Y, Aizawa H, Nakata T, Matsuura Y, et al. KIF3A is a new microtubule-based anterograde motor in the nerve axon. J Cell Biol. 1994;125(5):1095–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marszalek JR, Ruiz-Lozano P, Roberts E, Chien KR, Goldstein LS. Situs inversus and embryonic ciliary morphogenesis defects in mouse mutants lacking the KIF3A subunit of kinesin-II. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(9):5043–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scholey JM. Intraflagellar transport. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2003;19:423–43. 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.111401.091318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scholey JM. Kinesin-2: a family of heterotrimeric and homodimeric motors with diverse intracellular transport functions. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2013;29:443–69. 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-101512-122335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brugmann SA, Allen NC, James AW, Mekonnen Z, Madan E, Helms JA. A primary cilia-dependent etiology for midline facial disorders. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19(8):1577–92. 10.1093/hmg/ddq030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moyer JH, Lee-Tischler MJ, Kwon HY, Schrick JJ, Avner ED, Sweeney WE, et al. Candidate gene associated with a mutation causing recessive polycystic kidney disease in mice. Science. 1994;264(5163):1329–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoder BK, Richards WG, Sweeney WE, Wilkinson JE, Avener ED, Woychik RP. Insertional mutagenesis and molecular analysis of a new gene associated with polycystic kidney disease. Proc Assoc Am Physicians. 1995;107(3):314–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taschner M, Lorentzen E. The Intraflagellar Transport Machinery. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2016;8(10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marszalek JR, Liu X, Roberts EA, Chui D, Marth JD, Williams DS, et al. Genetic evidence for selective transport of opsin and arrestin by kinesin-II in mammalian photoreceptors. Cell. 2000;102(2):175–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haycraft CJ, Zhang Q, Song B, Jackson WS, Detloff PJ, Serra R, et al. Intraflagellar transport is essential for endochondral bone formation. Development. 2007;134(2):307–16. 10.1242/dev.02732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lakso M, Pichel JG, Gorman JR, Sauer B, Okamoto Y, Lee E, et al. Efficient in vivo manipulation of mouse genomic sequences at the zygote stage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(12):5860–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gorski JA, Talley T, Qiu M, Puelles L, Rubenstein JL, Jones KR. Cortical excitatory neurons and glia, but not GABAergic neurons, are produced in the Emx1-expressing lineage. J Neurosci. 2002;22(15):6309–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hebert JM, McConnell SK. Targeting of cre to the Foxg1 (BF-1) locus mediates loxP recombination in the telencephalon and other developing head structures. Dev Biol. 2000;222(2):296–306. 10.1006/dbio.2000.9732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Danielian PS, Muccino D, Rowitch DH, Michael SK, McMahon AP. Modification of gene activity in mouse embryos in utero by a tamoxifen-inducible form of Cre recombinase. Curr Biol. 1998;8(24):1323–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Macatee TL, Hammond BP, Arenkiel BR, Francis L, Frank DU, Moon AM. Ablation of specific expression domains reveals discrete functions of ectoderm- and endoderm-derived FGF8 during cardiovascular and pharyngeal development. Development. 2003;130(25):6361–74. 10.1242/dev.00850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Soriano P. Generalized lacZ expression with the ROSA26 Cre reporter strain. Nat Genet. 1999;21(1):70–1. 10.1038/5007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muzumdar MD, Tasic B, Miyamichi K, Li L, Luo L. A global double-fluorescent Cre reporter mouse. Genesis. 2007;45(9):593–605. 10.1002/dvg.20335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Behringer R. Manipulating the mouse embryo: a laboratory manual. Fourth edition ed. Cold Spring Harbor, New York: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2014. xxii, 814 pages p. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jiang X, Iseki S, Maxson RE, Sucov HM, Morriss-Kay GM. Tissue origins and interactions in the mammalian skull vault. Dev Biol. 2002;241(1):106–16. 10.1006/dbio.2001.0487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jiang X, Choudhary B, Merki E, Chien KR, Maxson RE, Sucov HM. Normal fate and altered function of the cardiac neural crest cell lineage in retinoic acid receptor mutant embryos. Mech Dev. 2002;117(1–2):115–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chai Y, Jiang X, Ito Y, Bringas P Jr., Han J, Rowitch DH, et al. Fate of the mammalian cranial neural crest during tooth and mandibular morphogenesis. Development. 2000;127(8):1671–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stottmann RW, Klingensmith J. Bone morphogenetic protein signaling is required in the dorsal neural folds before neurulation for the induction of spinal neural crest cells and dorsal neurons. Dev Dyn. 2011;240(4):755–65. 10.1002/dvdy.22579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilson SL, Wilson JP, Wang C, Wang B, McConnell SK. Primary cilia and Gli3 activity regulate cerebral cortical size. Dev Neurobiol. 2012;72(9):1196–212. 10.1002/dneu.20985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Petersen PH, Zou K, Hwang JK, Jan YN, Zhong W. Progenitor cell maintenance requires numb and numblike during mouse neurogenesis. Nature. 2002;419(6910):929–34. 10.1038/nature01124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhuo L, Theis M, Alvarez-Maya I, Brenner M, Willecke K, Messing A. hGFAP-cre transgenic mice for manipulation of glial and neuronal function in vivo. Genesis. 2001;31(2):85–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spassky N, Han YG, Aguilar A, Strehl L, Besse L, Laclef C, et al. Primary cilia are required for cerebellar development and Shh-dependent expansion of progenitor pool. Dev Biol. 2008;317(1):246–59. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.02.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Berbari NF, Malarkey EB, Yazdi SM, McNair AD, Kippe JM, Croyle MJ, et al. Hippocampal and cortical primary cilia are required for aversive memory in mice. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e106576 10.1371/journal.pone.0106576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Willaredt MA, Hasenpusch-Theil K, Gardner HA, Kitanovic I, Hirschfeld-Warneken VC, Gojak CP, et al. A crucial role for primary cilia in cortical morphogenesis. J Neurosci. 2008;28(48):12887–900. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2084-08.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Caspary T, Larkins CE, Anderson KV. The graded response to Sonic Hedgehog depends on cilia architecture. Dev Cell. 2007;12(5):767–78. 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Higginbotham H, Guo J, Yokota Y, Umberger NL, Su CY, Li J, et al. Arl13b-regulated cilia activities are essential for polarized radial glial scaffold formation. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16(8):1000–7. 10.1038/nn.3451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Andoniadou CL, Martinez-Barbera JP. Developmental mechanisms directing early anterior forebrain specification in vertebrates. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013;70(20):3739–52. 10.1007/s00018-013-1269-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beccari L, Marco-Ferreres R, Bovolenta P. The logic of gene regulatory networks in early vertebrate forebrain patterning. Mech Dev. 2013;130(2–3):95–111. 10.1016/j.mod.2012.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fossat N, Jones V, Garcia-Garcia MJ, Tam PP. Modulation of WNT signaling activity is key to the formation of the embryonic head. Cell Cycle. 2012;11(1):26–32. 10.4161/cc.11.1.18700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Corbit KC, Shyer AE, Dowdle WE, Gaulden J, Singla V, Chen MH, et al. Kif3a constrains beta-catenin-dependent Wnt signalling through dual ciliary and non-ciliary mechanisms. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10(1):70–6. 10.1038/ncb1670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Briscoe J, Therond PP. The mechanisms of Hedgehog signalling and its roles in development and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2013;14(7):416–29. 10.1038/nrm3598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Martinez-Barbera JP, Rodriguez TA, Beddington RS. The homeobox gene Hesx1 is required in the anterior neural ectoderm for normal forebrain formation. Dev Biol. 2000;223(2):422–30. 10.1006/dbio.2000.9757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sasaki H, Hui C, Nakafuku M, Kondoh H. A binding site for Gli proteins is essential for HNF-3beta floor plate enhancer activity in transgenics and can respond to Shh in vitro. Development. 1997;124(7):1313–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li XJ, Zhang X, Johnson MA, Wang ZB, Lavaute T, Zhang SC. Coordination of sonic hedgehog and Wnt signaling determines ventral and dorsal telencephalic neuron types from human embryonic stem cells. Development. 2009;136(23):4055–63. 10.1242/dev.036624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang L, Hou S, Han YG. Hedgehog signaling promotes basal progenitor expansion and the growth and folding of the neocortex. Nat Neurosci. 2016;19(7):888–96. 10.1038/nn.4307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chang CF, Ramaswamy G, Serra R. Depletion of primary cilia in articular chondrocytes results in reduced Gli3 repressor to activator ratio, increased Hedgehog signaling, and symptoms of early osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2012;20(2):152–61. 10.1016/j.joca.2011.11.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Haycraft CJ, Banizs B, Aydin-Son Y, Zhang Q, Michaud EJ, Yoder BK. Gli2 and Gli3 localize to cilia and require the intraflagellar transport protein polaris for processing and function. PLoS Genet. 2005;1(4):e53 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pazour GJ, Dickert BL, Vucica Y, Seeley ES, Rosenbaum JL, Witman GB, et al. Chlamydomonas IFT88 and its mouse homologue, polycystic kidney disease gene tg737, are required for assembly of cilia and flagella. J Cell Biol. 2000;151(3):709–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yoder BK, Hou X, Guay-Woodford LM. The polycystic kidney disease proteins, polycystin-1, polycystin-2, polaris, and cystin, are co-localized in renal cilia. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13(10):2508–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rohatgi R, Snell WJ. The ciliary membrane. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010;22(4):541–6. 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.03.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Baldari CT, Rosenbaum J. Intraflagellar transport: it's not just for cilia anymore. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010;22(1):75–80. 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.10.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper.