Abstract

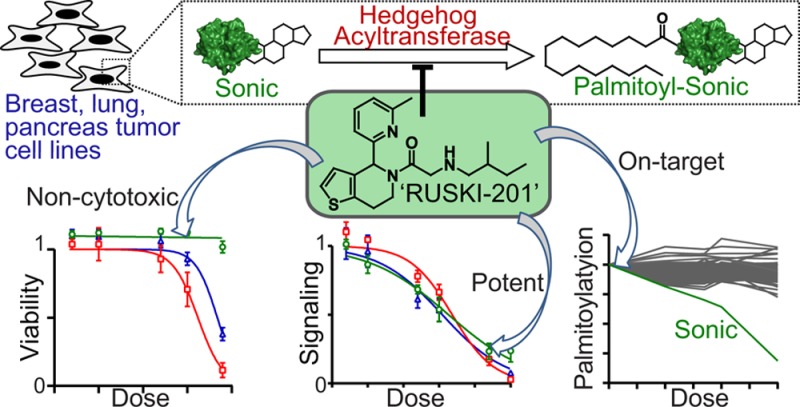

The Sonic Hedgehog (Shh) signaling pathway plays a critical role during embryonic development and cancer progression. N-terminal palmitoylation of Shh by Hedgehog acyltransferase (Hhat) is essential for efficient signaling, raising interest in Hhat as a novel drug target. A recently identified series of dihydrothienopyridines has been proposed to function via this mode of action; however, the lead compound in this series (RUSKI-43) was subsequently shown to possess cytotoxic activity unrelated to canonical Shh signaling. To identify a selective chemical probe for cellular studies, we profiled three RUSKI compounds in orthogonal cell-based assays. We found that RUSKI-43 exhibits off-target cytotoxicity, masking its effect on Hhat-dependent signaling, hence results obtained with this compound in cells should be treated with caution. In contrast, RUSKI-201 showed no off-target cytotoxicity, and quantitative whole-proteome palmitoylation profiling with a bioorthogonal alkyne-palmitate reporter demonstrated specific inhibition of Hhat in cells. RUSKI-201 is the first selective Hhat chemical probe in cells and should be used in future studies of Hhat catalytic function.

Hedgehog (Hh) signaling plays an essential role in the normal development of vertebrate species and is involved in processes such as organogenesis and tissue patterning, including digit formation and ventral forebrain neuron differentiation.1,2 In adult tissues, Hh signaling is normally restricted to functions such as differentiation of human thymocytes and bone remodeling,3,4 but is also aberrantly activated in a variety of diseases. Various cancers exhibit active Hh signaling, including medulloblastoma; basal cell carcinoma; osteosarcoma; and pancreatic, lung, breast, and prostate cancers.5,6 Aberrant Hh signaling is also observed in interstitial lung diseases, such as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.7

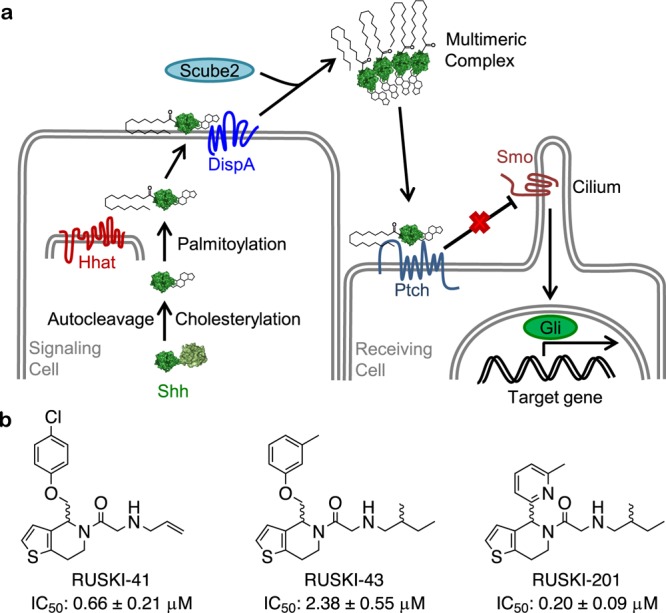

Hh signaling is mediated by the Hh family of proteins, which in humans comprises Sonic (Shh), Indian (Ihh), and Desert Hedgehog (Dhh). The function of these secreted morphogens is tightly regulated by the formation of morphogenic gradients and multimeric complexes.2,8 Proper function of Hh proteins requires dual post-translational lipidation via a cholesteryl ester at the C-terminal carboxylate and a palmitoyl amide at the N-terminal amine (Figure 1a).9 The full physiological role of these lipid modifications remains elusive, but cholesterylation appears to enhance activity and regulate the distance over which signaling persists,10−12 while genetic knockout of the palmitoylation site prevents signaling.2

Figure 1.

Hh signaling pathway and RUSKI Hhat inhibitors. (a) Canonical Hh signaling requires production of dually lipidated Shh signaling protein. Shh is C-terminally autocholesterylated and N-terminally palmitoylated by Hhat. Modified Shh is secreted and recognized by its receptor Ptch, which releases inhibition of Smo, thereby triggering downstream target expression under Gli promoter control. (b) Hhat inhibitors used in the current study and their reported IC50 values against recombinant Hhat.23

Mature Shh can induce signaling in an autocrine, juxtacrine, or paracrine fashion upon binding to the cognate receptor Patched (Ptch), by relieving Ptch inhibition of the G-protein-coupled receptor-like Smoothened (Smo). Smo is translocated to the primary cilium to activate further downstream signaling events, culminating in activation of Gli transcription factors and subsequent initiation of Hh-mediated transcription events (Figure 1a).5

Due to its activation in various cancers, Hh signaling has attracted significant interest for therapeutic intervention. Small molecule inhibitors of various components of the pathway have been identified and explored as potential therapeutics, Smo inhibitors in particular. One of the best characterized Smo inhibitors, GDC-0449, has progressed to clinical trials, showing some success;13 however, treatment is complicated by the emergence of resistant clones harboring Smo gene mutations leading to hyper-activated Hh signaling that is resistant to Smo inhibitors.14

Hedgehog acyltransferase (Hhat) is a multipass transmembrane protein found in the endoplasmic reticulum15 and is a member of the membrane bound O-acyltransferase superfamily of proteins.16 Hhat is responsible for N-palmitoylation of Hh proteins,17 and Hhat knockout mice display similar phenotypes to Shh knockouts, exhibiting developmental defects and neonatal lethality.2 Given the critical importance of palmitoylation for Hh ligand activity, it has been proposed that Hhat inhibition could provide an alternative means to block Hh signaling. A recent small molecule screen against recombinant Hhat by Resh and co-workers identified a series of 5-acyl-6,7-dihydrothieno[3,2-c]pyridines.18 Compounds in this so-called “RUSKI” class represent the first small molecule inhibitors of Hhat, of which RUSKI-43 (Figure 1b) has been used as a chemical probe for Hhat inhibition in subsequent studies in cells.19,20 RUSKI-43 is claimed to be a potent and specific inhibitor of Shh palmitoylation, thereby arresting autocrine and paracrine Hh signaling, and is proposed to have therapeutic potential for Hh-dependent cancers.19,20 Surprisingly, the cytotoxicity of RUSKI-43 did not correlate with Hh signaling, and the authors attributed this phenotype to an unspecified “hedgehog-independent” function of Hhat. However, these observations are also consistent with nonspecific cellular toxicity in addition to inhibition of Hhat activity, raising questions over the validity of this compound as a probe in cellular studies.21 We concluded that further evidence for on-target activity without generic toxicity is required in order to validate the RUSKI series as probes for Hhat activity.

We have previously reported the novel synthesis of a number of RUSKI analogs and demonstrated their inhibitory activity against recombinant Hhat.22−24 We therefore sought to employ a combination of cell biology and chemical proteomic analysis to assess the potency and specific target engagement by selected RUSKI compounds (Figure 1b) in cells and characterize their mode of action.

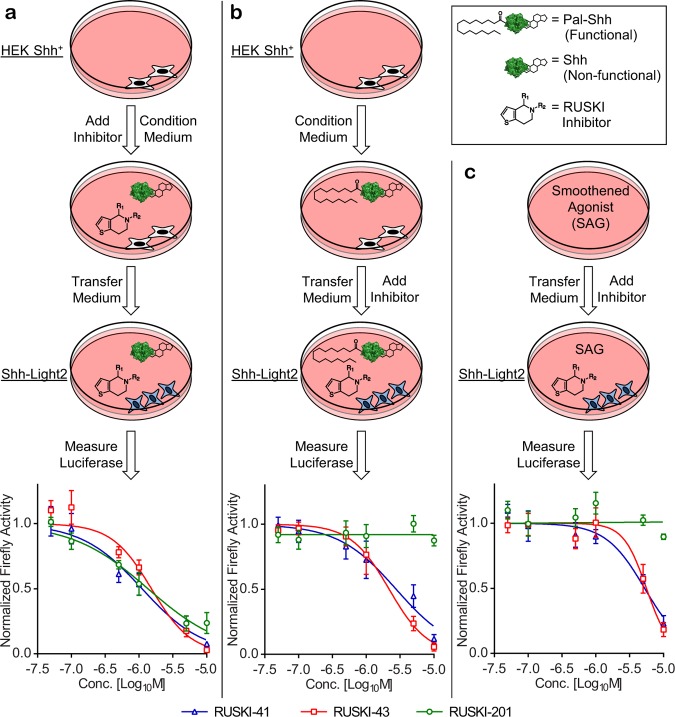

Shh-Light2 cells are derived from NIH3T3 cells stably transfected with a Gli-responsive firefly luciferase and a constitutively expressed Renilla luciferase as an internal control for cell density, and are widely used to study activation and inhibition of canonical Hh signaling.25 HEK-293 cells stably overexpressing Shh (HEK-293 Shh+)26 were treated with RUSKI-41, RUSKI-43, or RUSKI-201 for 24 h. The conditioned media from these cells containing secreted Shh were incubated with Shh-Light2 cells for 48 h prior to recording firefly and Renilla luciferase activity. All RUSKI compounds inhibited firefly luciferase activity in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 2a) consistent with activity against Hhat in biochemical assays.18,23 However, a loss of firefly luciferase signal is not unequivocal evidence for inhibition of Shh palmitoylation, since inhibitors may target other processes in the reporter cell line. To isolate such off-target effects from Hhat inhibition, compounds were added to conditioned medium from untreated HEK-293 Shh+ immediately prior to incubation with reporter cells (Figure 2b). RUSKI-41 and RUSKI-43 inhibited firefly luciferase activity despite the presence of palmitoylated Shh in the conditioned media, while RUSKI-201 had no effect under the same conditions. To further probe off-pathway effects, Shh-Light2 cells were treated with RUSKI compounds in the presence of a small molecule Smo agonist (SAG), which activates Hh signaling downstream of Ptch (Supporting Information Figure S1) rendering Gli activation independent of Shh.27,28 Under these Shh-independent conditions, RUSKI-41 and RUSKI-43 induced a significant reduction in firefly luciferase activity, while RUSKI-201 had no effect (Figure 2c). These findings clearly indicate that RUSKI-41 and RUSKI-43 inhibit signaling independent of Hhat inhibition, regardless of any corresponding reduction of the palmitoylation state of Shh. Furthermore, inhibition cannot be rescued by Smo-mediated stimulation of the pathway downstream of Shh, indicating modes of action unrelated to either Hhat or canonical Hh signaling. Cell survival in Shh-Light2 cells is independent of the Hh pathway; however, cell viability measurements showed a trend of substantial Shh-Light2 cytotoxicity for RUSKI-41 and RUSKI-43 (EC50 = 21 ± 1.4 μM and 11 ± 2.5 μM, respectively), whereas RUSKI-201 had no effect on cell viability at concentrations >25 μM (Supporting Information Figure S2). Furthermore, Renilla luciferase activity was significantly inhibited by RUSKI-41 and RUSKI-43 but unaffected by RUSKI-201 (Supporting Information Figure S3). To further test the selectivity for Hhat over the related MBOAT family member Porcupine (PORCN, responsible for Wnt palmitoylation), we utilized a Wnt cellular signaling assay. Mouse TM3 cells expressing luciferase under control of a Wnt signaling promoter with constitutive Renilla expression29 were treated with RUSKI-201 and RUSKI-43 (10 μM) alongside positive control PORCN inhibitor LGK974 (100 nM).30 RUSKI-201 exhibited excellent selectivity with no effect on Wnt signaling, whereas RUSKI-43 exhibited approximately 50% reduction in signaling (Supporting Information Figure S4). Since RUSKI-43 has previously been demonstrated not to inhibit Wnt palmitoylation by PORCN,18 it may be concluded that the observed inhibition of Wnt signaling by RUSKI-43 also arises through an off-target mode-of-action.

Figure 2.

Inhibition of canonical Hh signaling by RUSKI compounds. The effects of RUSKI-41 (blue), RUSKI-43 (red), and RUSKI-201 (green) on Shh signaling were characterized as described in the Materials and Methods. (a) Addition of inhibitors to HEK-293 Shh+ and subsequent transfer of conditioned medium to reporter cells; under these conditions, all compounds inhibit the firefly luciferase reporter signal. (b) Addition of inhibitors to preconditioned medium and immediate transfer to reporter cells indicates RUSKI-41 and RUSKI-43 inhibit the firefly reporter regardless of Shh palmitoylation status. (c) Addition of inhibitors to SAG-containing medium prior to transfer to reporter cells indicates RUSKI-41 and RUSKI-43 inhibition cannot be rescued by downstream pathway stimulation. In each case, RUSKI-201 behaves as a canonical Hhat inhibitor. Renilla luciferase activity was inhibited by RUSKI-41 and RUSKI-43 and unaffected by RUSKI-201 (Supporting Information Figure S3). Response is normalized to vehicle control, and data represent mean ± SEM of experiments performed in triplicate (n ≥ 3).

We next sought to probe on-target Shh palmitoylation inhibition by RUSKI-201 in cells using bio-orthogonal tagging technology.31 HEK-293 Shh+ cells were treated with RUSKI-201 for 7 h, with the addition of alkyne-tagged palmitic acid (YnPal) after 1 h to monitor protein palmitoylation. YnPal is processed as the natural substrate and incorporated into the acylation sites of palmitoylated proteins, including Shh.11,32,33 YnPal-tagged proteins were ligated to azido-TAMRA-PEG3-biotin (AzTB) trifunctional capture reagent (Supporting Information Figure S5)34−36via copper(I)-catalyzed azide–alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC). Ligation of AzTB to YnPal-Shh results in a ∼2 kDa apparent mass increase compared to untagged Shh by anti-Shh Western Blot (WB) (Figure 3a);11 WB analysis of tagged and nontagged Shh indicated that YnPal was incorporated into ∼10% of total cellular Shh, comparable to previous reports.11,32,33 The overall level of YnPal-tagged proteins assessed by in-gel fluorescence was unchanged by RUSKI-201 treatment, indicating global palmitoylation was unaffected (Figure 3a). Inhibition of YnPal-tagging of Shh as measured by tagging IC50 (TC50) was 0.87 ± 0.08 μM (Figure 3b), in good agreement with previous assays in Shh-Light2 cells (IC50 = 2.3 ± 1.2 μM). In order to measure the impact of RUSKI-201 across the palmitoyl proteome, we employed a spike-in stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture (SILAC)-based quantitative proteomics approach.32 HEK-293 Shh+ cells labeled with heavy isotope amino acids (R10K8; l-arginine-13C6, 15C4, l-lysine-13C6, 15C2) were treated with YnPal for 6 h to produce a lysate heavy standard that was mixed 1:1 with lysate from cells treated with RUSKI-201 and YnPal in standard medium, and the mixed lysate ligated to the capture reagent (Supporting Information Figure S5).37 Labeled proteins were then enriched on NeutrAvidin resin, trypsin digested, and light/heavy ratios of recovered peptides determined by nanoLC-MS/MS to provide fold change values for the palmitoylation state of 105 proteins across a series of RUSKI-201 concentrations (Supporting Information Table 1). Hh ligand palmitoylation was reduced in a dose-dependent manner, while there was no significant change in the modification state of all other proteins detected (Figure 3c). This is as expected as Hh signaling proteins are the only known substrates of Hhat,38 and the large majority of post-translational protein S-palmitoylation is known to be undertaken by the structurally unrelated DHHC family of palmitoyl transferases. RUSKI-201 exhibited submicromolar potency (IC50 = 0.73 ± 0.09 μM, Figure 3d) in close agreement with the TC50 from WB analysis. Taken together, these data are consistent with selective inhibition of Shh palmitoylation by Hhat in cells by RUSKI-201, and with Hhat-dependent inhibition of Shh-dependent signaling in the Shh-Light2 assay. Our data strongly suggest that Hhat inhibition does not affect global palmitoylation levels, for example by inhibiting other palmitoyl transferases or acyl-protein thioesterases,32 and is consistent with a mutually specific enzyme–substrate relationship between Hhat and Hh ligands.38 RUSKI-41 also inhibited only Hh palmitoylation (Supporting Information Figure S6, Table S2), strongly suggesting that these inhibitors do not inhibit some putative alternative Hhat-mediated palmitoylation event, and further supporting the proposed off-target activity of these compounds.

Figure 3.

Selective inhibition of Shh palmitoylation by RUSKI-201. HEK-293 Shh+ cells were treated with RUSKI-201 followed by YnPal and functionalized with AzTB as described in the Materials and Methods. (a) In-gel fluorescence and Shh and tubulin WB indicates selective inhibition of Shh palmitoylation by RUSKI-201. Images representative of six biological replicates. (b) TC50 dose–response curve of α-Shh blot shown in a (TC50 = 0.87 ± 0.08 μM, n = 6). (c) Change in L/H ratio upon RUSKI-201 treatment from spike-in SILAC quantitative proteomics. Each line represents a protein known to be palmitoylated, normalized to inhibitor vehicle control. Green line represents Hh proteins (Shh, Dhh, Ihh; n ≥ 2). (d) IC50 dose–response curve of quantitative proteomics data shown in c (IC50 0.73 ± 0.09 μM, n ≥ 2). Data represent mean ± SEM of experiments performed in duplicate.

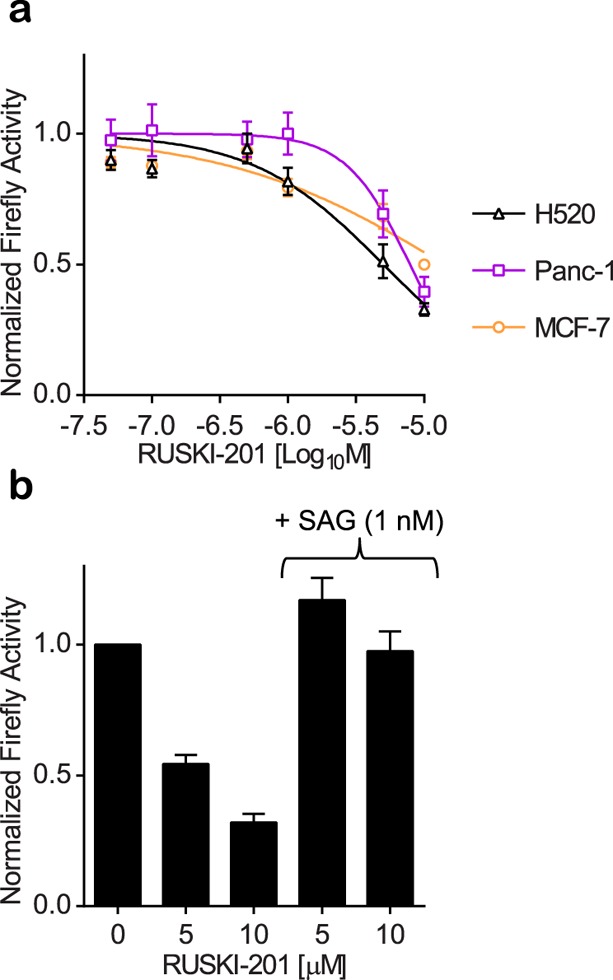

Having validated RUSKI-201 as a potent and selective inhibitor of Hhat in cells, capable of blocking Hh signaling from Shh overexpressing cells, we next sought to investigate the arrest of Hh signaling from tumor cells. Transcript analyses were used to confirm Hhat and Shh expression in a panel of one breast cancer, four pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), and seven nonsmall cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cell lines (Supporting Information Figure S7). Measurement of Gli1 activation in coculture with Shh-Light2 cells indicated that H520 (NSCLC), Panc-1 (PDAC), and MCF-7 (breast) secrete active Shh (Supporting Information Figure S8). Dose–response studies using Smo inhibitor GDC-0449 confirmed that Hh signaling in these cell lines occurred in a canonical manner, with inhibition in the low nanomolar range (Supporting Information Figure S8). RUSKI-201 also inhibited signaling in H520, Panc-1, and MCF-7 coculture with Shh-Light2 cells (IC50 = 4.8 ± 0.60 μM, 7.8 ± 1.3 μM, and 8.5 ± 0.65 μM, respectively; Figure 4a). Cell viability assays have previously shown Panc-1 and MCF-7 cells to be growth sensitive to RUSKI-43.19,20 We therefore tested the effect of RUSKI-43 on Panc-1 and MCF-7 viability alongside on-target inhibitors of Smo (GDC-0449) and Hhat (RUSKI-201). Neither on-target inhibitor affected viability, whereas RUSKI-43 displayed significant cytotoxic effects against Panc-1 and MCF-7 cells (EC50 = 7.4 ± 0.49 μM and 13 ± 0.27 μM, respectively; Supporting Information Figure S9). Additionally, RUSKI-201 and GDC-0449 had no impact on either Renilla luciferase expression in Shh-Light2 cells (Supporting Information Figures S8 and S10), or viability in either tumor or Shh-Light2 cells (Supporting Information Figure S11); this is consistent with a lack of cell-autonomous dependence on Hh signaling in these lines and confirms that on-target inhibitors of Hhat or of canonical Hh signaling do not induce cell-autonomous cytotoxic effects (Supporting Information Figures S2 and S3). Finally, RUSKI-201 inhibition of signaling by Shh in H520 cells cocultured with Shh-Light2 cells was efficiently rescued by SAG pathway stimulation (Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

RUSKI-201 inhibition of Hh signaling induced by tumor cells. (a) Tumor cell lines capable of juxtacrine and/or paracrine signaling (Supporting Information Figure S8) exhibited dose-dependent inhibition of Gli activation in SHH-Light2 cells by RUSKI-201. Renilla luciferase activity was unaffected (Supporting Information Figure S10). (b) Treatment of H520/Shh-Light2 cocultures with RUSKI-201 ± SAG indicates rescue of Hh signaling upon SAG treatment. Response normalized to vehicle control. Data represent mean ± SEM of experiments performed at least in triplicate (n ≥ 3).

These data demonstrate that RUSKI-201 can inhibit endogenous Hh signaling from tumor cell lines, which has been proposed as a potential treatment for various cancers.20,26 Instead of blocking Hh signaling at large numbers of receiving cells (as would occur with a Smo inhibitor), Hhat inhibition would disrupt paracrine signaling at its source in Shh-producing tumor cells. Stromal desmoplasia resulting from tumor-promoted Hh signaling is thought to offer a protective environment for tumors that limits access of chemotherapeutic drugs.39,40 The therapeutic benefit of disruption of stromal desmoplasia is currently debated;41,42 however, complete inhibition of Hh signaling has been shown to block tumor promotion.43 This complex outcome of Hh inhibition highlights the need for improved understanding of this pathway on the biochemical, cellular, and whole-organism level. Chemical biology has the potential to greatly expedite such studies; however, as with any investigation, the selection of appropriate (chemical) tools is of critical importance.21,44−47 The on-target mode of action of RUSKI-201 makes it the optimal tool molecule currently available to study Hhat function. Our previous reports provide straightforward synthetic access to this class of inhibitors,22,24 which will facilitate investigation of structure–activity relationships and pharmacophore determination and enable their continued development as chemical tools or therapeutics.

In summary, we have used a range of cellular assays to demonstrate that the commonly employed Hhat inhibitor RUSKI-43 possesses significant cytotoxicity at concentrations relevant to Hhat inhibition and that this results from Hhat- and Hh-independent activity that cannot be rescued via Hh pathway stimulation. However, RUSKI-201 was shown to induce Hhat- and Hh-dependent inhibition in a range of cell lines, including tumor cells, and selectively inhibits Hh palmitoylation over a panel of >100 palmitoylated substrates in cells. These data strongly suggest that RUSKI-201 is the superior and preferred chemical probe for small molecule inhibition of Hhat catalytic function.21,44−47

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Suzanne Eaton for the kind gift of the Shh-Light2 cells and Prof. Lawrence Lum for the kind gifts of the Wnt reporter cell line and LGK974 inhibitor. This work was supported by Cancer Research UK (CRUK, C6433/A16402). N.M. held a Ph.D. studentship from the Imperial College London Institute of Chemical Biology, Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) Centre for Doctoral Training (EP/F500416/1). M.R. was generously funded by a Marie Curie Intra European Fellowship from the European Commission’s Research Executive Agency (FP7-PEOPLE-2013-IEF). J.B. and R.B. are supported by Cancer Research UK (grant number C309/A11566).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acschembio.6b00896.

Supporting Information figures, tables of identified proteins, and material and methods (PDF)

Author Present Address

∥ Electron Microscopy Unit, Royal Brompton Hospital, The Institute of Cancer Research, London, SW3 6NP, United Kingdom

Author Present Address

⊥ Imanova Limited, Hammersmith Hospital, London, W12 0NN, United Kingdom

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Ericson J.; Muhr J.; Placzek M.; Lints T.; Jessel T. M.; Edlund T. (1995) Sonic hedgehog induces the differentiation of ventral forebrain neurons: a common signal for ventral patterning within the neural tube. Cell 81, 747–756. 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90536-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M.-H.; Li Y.-J.; Kawakami T.; Xu S.-M.; Chuang P.-T. (2004) Palmitoylation is required for the production of a soluble multimeric Hedgehog protein complex and long-range signaling in vertebrates. Genes Dev. 18, 641–659. 10.1101/gad.1185804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacedón R.; Varas A.; Hernández-López C.; Gutiérrez-deFrías C.; Crompton T.; Zapata A. G.; Vicente A. (2003) Expression of hedgehog proteins in the human thymus. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 51, 1557–1566. 10.1177/002215540305101115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannonier S. A.; Sterling J. A. (2015) The Role of Hedgehog Signaling in Tumor Induced Bone Disease. Cancers 7, 1658–1683. 10.3390/cancers7030856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barakat M. T.; Humke E. W.; Scott M. P. (2010) Learning from Jekyll to control Hyde: Hedgehog signaling in development and cancer. Trends Mol. Med. 16, 337–348. 10.1016/j.molmed.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirotsu M.; Setoguchi T.; Sasaki H.; Matsunoshita Y.; Gao H.; Nagao H.; Kunigou O.; Komiya S. (2010) Smoothened as a new therapeutic target for human osteosarcoma. Mol. Cancer 9, 5. 10.1186/1476-4598-9-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolaños A. L.; Milla C. M.; Lira J. C.; Ramírez R.; Checa M.; Barrera L.; García-Alvarez J.; Carbajal V.; Becerril C.; Gaxiola M.; Pardo A.; Selman M. (2012) Role of Sonic Hedgehog in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 303, L978–990. 10.1152/ajplung.00184.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gritli-Linde A.; Lewis P.; McMahon A. P.; Linde A. (2001) The whereabouts of a morphogen: direct evidence for short- and graded long-range activity of hedgehog signaling peptides. Dev. Biol. 236, 364–386. 10.1006/dbio.2001.0336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepinsky R. B.; Zeng C.; Wen D.; Rayhorn P.; Baker D. P.; Williams K. P.; Bixler S. A.; Ambrose C. M.; Garber E. A.; Miatkowski K.; Taylor F. R.; Wang E. A.; Galdes A. (1998) Identification of a palmitic acid-modified form of human Sonic hedgehog. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 14037–14045. 10.1074/jbc.273.22.14037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawber R. J.; Hebbes S.; Herpers B.; Docquier F.; van den Heuvel M. (2005) Differential range and activity of various forms of the Hedgehog protein. BMC Dev. Biol. 5, 21. 10.1186/1471-213X-5-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciepla P.; Konitsiotis A. D.; Serwa R. A.; Masumoto N.; Leong W. P.; Dallman M. J.; Magee A. I.; Tate E. W. (2014) New chemical probes targeting cholesterylation of Sonic Hedgehog in human cells and zebrafish. Chem. Sci. R. Soc. Chem. 2010 5, 4249–4259. 10.1039/C4SC01600A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciepla P.; Magee A. I.; Tate E. W. (2015) Cholesterylation: a tail of hedgehog. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 43, 262–267. 10.1042/BST20150032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekulic A.; Migden M. R.; Oro A. E.; Dirix L.; Lewis K. D.; Hainsworth J. D.; Solomon J. A.; Yoo S.; Arron S. T.; Friedlander P. A.; Marmur E.; Rudin C. M.; Chang A. L. S.; Low J. A.; Mackey H. M.; Yauch R. L.; Graham R. A.; Reddy J. C.; Hauschild A. (2012) Efficacy and safety of vismodegib in advanced basal-cell carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 366, 2171–2179. 10.1056/NEJMoa1113713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atwood S. X.; Sarin K. Y.; Whitson R. J.; Li J. R.; Kim G.; Rezaee M.; Ally M. S.; Kim J.; Yao C.; Chang A. L. S.; Oro A. E.; Tang J. Y. (2015) Smoothened variants explain the majority of drug resistance in basal cell carcinoma. Cancer Cell 27, 342–353. 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konitsiotis A. D.; Jovanović B.; Ciepla P.; Spitaler M.; Lanyon-Hogg T.; Tate E. W.; Magee A. I. (2015) Topological analysis of Hedgehog acyltransferase, a multipalmitoylated transmembrane protein. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 3293–3307. 10.1074/jbc.M114.614578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masumoto N.; Lanyon-Hogg T.; Rodgers U. R.; Konitsiotis A. D.; Magee A. I.; Tate E. W. (2015) Membrane bound O-acyltransferases and their inhibitors. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 43, 246–252. 10.1042/BST20150018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buglino J. A.; Resh M. D. (2008) Hhat is a palmitoylacyltransferase with specificity for N-palmitoylation of Sonic Hedgehog. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 22076–22088. 10.1074/jbc.M803901200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrova E.; Rios-Esteves J.; Ouerfelli O.; Glickman J. F.; Resh M. D. (2013) Inhibitors of Hedgehog acyltransferase block Sonic Hedgehog signaling. Nat. Chem. Biol. 9, 247–249. 10.1038/nchembio.1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrova E.; Matevossian A.; Resh M. D. (2015) Hedgehog acyltransferase as a target in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Oncogene 34, 263–268. 10.1038/onc.2013.575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matevossian A.; Resh M. D. (2015) Hedgehog Acyltransferase as a target in estrogen receptor positive, HER2 amplified, and tamoxifen resistant breast cancer cells. Mol. Cancer 14, 72. 10.1186/s12943-015-0345-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrowsmith C. H.; Audia J. E.; Austin C.; Baell J.; Bennett J.; Blagg J.; Bountra C.; Brennan P. E.; Brown P. J.; Bunnage M. E.; Buser-Doepner C.; Campbell R. M.; Carter A. J.; Cohen P.; Copeland R. A.; Cravatt B.; Dahlin J. L.; Dhanak D.; Edwards A. M.; Frederiksen M.; Frye S. V.; Gray N.; Grimshaw C. E.; Hepworth D.; Howe T.; Huber K. V. M; Jin J.; Knapp S.; Kotz J. D.; Kruger R. G.; Lowe D.; Mader M. M.; Marsden B.; Mueller-Fahrnow A.; Müller S.; O’Hagan R. C.; Overington J. P.; Owen D. R.; Rosenberg S. H.; Ross R.; Roth B.; Schapira M.; Schreiber S. L.; Shoichet B.; Sundström M.; Superti-Furga G.; Taunton J.; Toledo-Sherman L.; Walpole C.; Walters M. A.; Willson T. M.; Workman P.; Young R. N.; Zuercher W. J. (2015) The promise and peril of chemical probes. Nat. Chem. Biol. 11, 536–541. 10.1038/nchembio.1867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanyon-Hogg T.; Ritzefeld M.; Masumoto N.; Magee A. I.; Rzepa H. S.; Tate E. W. (2015) Modulation of Amide Bond Rotamers in 5-Acyl-6,7-dihydrothieno[3,2-c]pyridines. J. Org. Chem. 80, 4370–4377. 10.1021/acs.joc.5b00205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanyon-Hogg T.; Masumoto N.; Bodakh G.; Konitsiotis A. D.; Thinon E.; Rodgers U. R.; Owens R. J.; Magee A. I.; Tate E. W. (2015) Click chemistry armed enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay to measure palmitoylation by hedgehog acyltransferase. Anal. Biochem. 490, 66–72. 10.1016/j.ab.2015.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanyon-Hogg T.; Masumoto N.; Bodakh G.; Konitsiotis A. D.; Thinon E.; Rodgers U. R.; Owens R. J.; Magee A. I.; Tate E. W. (2016) Synthesis and characterisation of 5-acyl-6,7-dihydrothieno[3,2-c]pyridine inhibitors of Hedgehog acyltransferase. Data Brief 7, 257–281. 10.1016/j.dib.2016.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taipale J.; Chen J. K.; Cooper M. K.; Wang B.; Mann R. K.; Milenkovic L.; Scott M. P.; Beachy P. A. (2000) Effects of oncogenic mutations in Smoothened and Patched can be reversed by cyclopamine. Nature 406, 1005–1009. 10.1038/35023008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konitsiotis A. D.; Chang S.-C.; Jovanović B.; Ciepla P.; Masumoto N.; Palmer C. P.; Tate E. W.; Couchman J. R.; Magee A. I. (2014) Attenuation of hedgehog acyltransferase-catalyzed sonic Hedgehog palmitoylation causes reduced signaling, proliferation and invasiveness of human carcinoma cells. PLoS One 9, e89899. 10.1371/journal.pone.0089899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank-Kamenetsky M.; Zhang X. M.; Bottega S.; Guicherit O.; Wichterle H.; Dudek H.; Bumcrot D.; Wang F. Y.; Jones S.; Shulok J.; Rubin L. L.; Porter J. A. (2002) Small-molecule modulators of Hedgehog signaling: identification and characterization of Smoothened agonists and antagonists. J. Biol. 1, 10. 10.1186/1475-4924-1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J. K.; Taipale J.; Young K. E.; Maiti T.; Beachy P. A. (2002) Small molecule modulation of Smoothened activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99, 14071–14076. 10.1073/pnas.182542899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B.; Dodge M. E.; Tang W.; Lu J.; Ma Z.; Fan C.-W.; Wei S.; Hao W.; Kilgore J.; Williams N. S.; Roth M. G.; Amatruda J. F.; Chen C.; Lum L. (2009) Small molecule-mediated disruption of Wnt-dependent signaling in tissue regeneration and cancer. Nat. Chem. Biol. 5, 100–107. 10.1038/nchembio.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.; Pan S.; Hsieh M. H.; Ng N.; Sun F.; Wang T.; Kasibhatla S.; Schuller A. G.; Li A. G.; Cheng D.; Li J.; Tompkins C.; Pferdekamper A.; Steffy A.; Cheng J.; Kowal C.; Phung V.; Guo G.; Wang Y.; Graham M. P.; Flynn S.; Brenner J. C.; Li C.; Villarroel M. C.; Schultz P. G.; Wu X.; McNamara P.; Sellers W. R.; Petruzzelli L.; Boral A. L.; Seidel H. M.; McLaughlin M. E.; Che J.; Carey T. E.; Vanasse G.; Harris J. L. (2013) Targeting Wnt-driven cancer through the inhibition of Porcupine by LGK974. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 110, 20224–20229. 10.1073/pnas.1314239110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tate E. W.; Kalesh K. A.; Lanyon-Hogg T.; Storck E. M.; Thinon E. (2015) Global profiling of protein lipidation using chemical proteomic technologies. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 24, 48–57. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2014.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin B. R.; Wang C.; Adibekian A.; Tully S. E.; Cravatt B. F. (2012) Global profiling of dynamic protein palmitoylation. Nat. Methods 9, 84–89. 10.1038/nmeth.1769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heal W. P.; Jovanovic B.; Bessin S.; Wright M. H.; Magee A. I.; Tate E. W. (2011) Bioorthogonal chemical tagging of protein cholesterylation in living cells. Chem. Commun. 47, 4081–4083. 10.1039/c0cc04710d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heal W. P.; Wright M. H.; Thinon E.; Tate E. W. (2012) Multifunctional protein labeling via enzymatic N-terminal tagging and elaboration by click chemistry. Nat. Protoc. 7, 105–117. 10.1038/nprot.2011.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright M. H.; Clough B.; Rackham M. D.; Rangachari K.; Brannigan J. A.; Grainger M.; Moss D. K.; Bottrill A. R.; Heal W. P.; Broncel M.; Serwa R. A.; Brady D.; Mann D. J.; Leatherbarrow R. J.; Tewari R.; Wilkinson A. J.; Holder A. A.; Tate E. W. (2014) Validation of N-myristoyltransferase as an antimalarial drug target using an integrated chemical biology approach. Nat. Chem. 6, 112–121. 10.1038/nchem.1830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thinon E.; Serwa R. A.; Broncel M.; Brannigan J. A.; Brassat U.; Wright M. H.; Heal W. P.; Wilkinson A. J.; Mann D. J.; Tate E. W. (2014) Global profiling of co- and post-translationally N-myristoylated proteomes in human cells. Nat. Commun. 5, 4919. 10.1038/ncomms5919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broncel M.; Serwa R. A.; Ciepla P.; Krause E.; Dallman M. J.; Magee A. I.; Tate E. W. (2015) Multifunctional reagents for quantitative proteome-wide analysis of protein modification in human cells and dynamic profiling of protein lipidation during vertebrate development. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 54, 5948–5951. 10.1002/anie.201500342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy R. Y.; Resh M. D. (2012) Identification of N-terminal residues of Sonic Hedgehog important for palmitoylation by Hedgehog acyltransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 42881–42889. 10.1074/jbc.M112.426833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olive K. P.; Jacobetz M. A.; Davidson C. J.; Gopinathan A.; McIntyre D.; Honess D.; Madhu B.; Goldgraben M. A.; Caldwell M. E.; Allard D.; Frese K. K.; Denicola G.; Feig C.; Combs C.; Winter S. P.; Ireland-Zecchini H.; Reichelt S.; Howat W. J.; Chang A.; Dhara M.; Wang L.; Rückert F.; Grützmann R.; Pilarsky C.; Izeradjene K.; Hingorani S. R.; Huang P.; Davies S. E.; Plunkett W.; Egorin M.; Hruban R. H.; Whitebread N.; McGovern K.; Adams J.; Iacobuzio-Donahue C.; Griffiths J.; Tuveson D. A. (2009) Inhibition of Hedgehog signaling enhances delivery of chemotherapy in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer. Science 324, 1457–1461. 10.1126/science.1171362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey J. M.; Swanson B. J.; Hamada T.; Eggers J. P.; Singh P. K.; Caffery T.; Ouellette M. M.; Hollingsworth M. A. (2008) Sonic hedgehog promotes desmoplasia in pancreatic cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 14, 5995–6004. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. J.; Perera R. M.; Wang H.; Wu D.-C.; Liu X. S.; Han S.; Fitamant J.; Jones P. D.; Ghanta K. S.; Kawano S.; Nagle J. M.; Deshpande V.; Boucher Y.; Kato T.; Chen J. K.; Willmann J. K.; Bardeesy N.; Beachy P. A. (2014) Stromal response to Hedgehog signaling restrains pancreatic cancer progression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 111, E3091–3100. 10.1073/pnas.1411679111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhim A. D.; Oberstein P. E.; Thomas D. H.; Mirek E. T.; Palermo C. F.; Sastra S. A.; Dekleva E. N.; Saunders T.; Becerra C. P.; Tattersall I. W.; Westphalen C. B.; Kitajewski J.; Fernandez-Barrena M. G.; Fernandez-Zapico M. E.; Iacobuzio-Donahue C.; Olive K. P.; Stanger B. Z. (2014) Stromal elements act to restrain, rather than support, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell 25, 735–747. 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew E.; Zhang Y.; Holtz A. M.; Kane K. T.; Song J. Y.; Allen B. L.; Pasca di Magliano M. (2014) Dosage-dependent regulation of pancreatic cancer growth and angiogenesis by hedgehog signaling. Cell Rep. 9, 484–494. 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frye S. V. (2010) The art of the chemical probe. Nat. Chem. Biol. 6, 159–161. 10.1038/nchembio.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Workman P.; Collins I. (2010) Probing the Probes: Fitness Factors For Small Molecule Tools. Chem. Biol. 17, 561–577. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunnage M. E.; Chekler E. L. P.; Jones L. H. (2013) Target validation using chemical probes. Nat. Chem. Biol. 9, 195–199. 10.1038/nchembio.1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blagg J.; Workman P. (2014) Chemical biology approaches to target validation in cancer. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 17, 87–100. 10.1016/j.coph.2014.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.