Abstract

Background

Obstructive jaundice caused due to bile duct tumor thrombus (BDTT) in a hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patient is an uncommon event. This study reports our clinical experiences and evaluates the outcomes of HCC patients with BDTT in a single institution.

Methods

A retrospective review of 19 HCC patients with secondary obstructive jaundice caused due to BDTT during a 15-year period was conducted.

Results

At the time of diagnosis, 14 (73.7%) patients had obstructive jaundice. Eighteen (94.7%) patients were preoperatively suspected of “obstruction of the bile duct”. Sixteen patients (84.2%) underwent a hepatectomy with curative intent, while two patients underwent removal of BDTT combined with biliary decompression and another patient received only palliative care as his liver reserve and general condition could not tolerate the primary tumor resection. The overall early recurrence (within 1 year) after hepatectomy occurred in more than half (9/16, 56.3%) of our patients. The 1-year survival rate of patients was 75% (12/16). The longest disease-free survival time was >11 years.

Conclusion

Identification of HCC patients with obstructive jaundice is clinically important because proper treatment can offer an opportunity for a cure and favorable long-term survival.

Keywords: hepatocellular carcinoma, biliary thrombosis, hepatectomy, recurrence, survival

Introduction

Obstructive jaundice caused due to bile duct tumor thrombus (BDTT) is an uncommon event in a hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patient. The incidence ranges from 1% to 12.9% in autopsy and surgical specimens.1–6 Few published reports exist regarding HCC with obstructive jaundice caused due to BDTT, and these patients are often misdiagnosed as having cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) or choledocholithiasis.3,7 Improvement of diagnosis imaging and more awareness regarding the recognition of this type of disease will increase the incidence of a correct preoperative diagnosis and further effective treatment planning.1–3,8–11 Thailand has a high incidence of HCC and liver cirrhosis.12 In this study, we summarize our clinical experiences and evaluate the results of different treatment modalities of 19 cases of this type of HCC during the past 15 years in a single high-volume institution in the north of Thailand.

Materials and methods

Population and clinical features

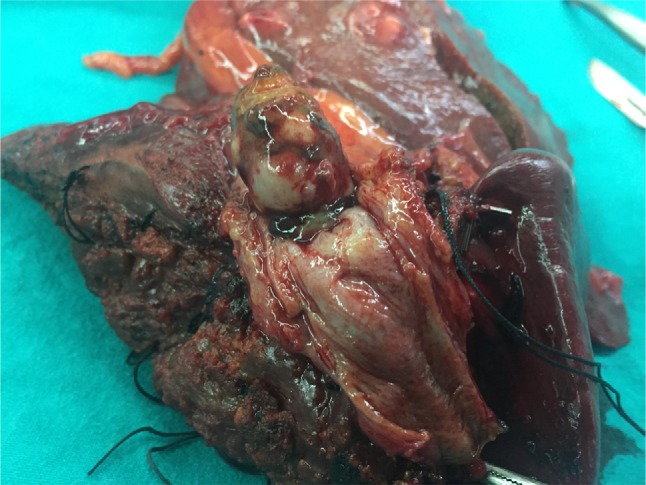

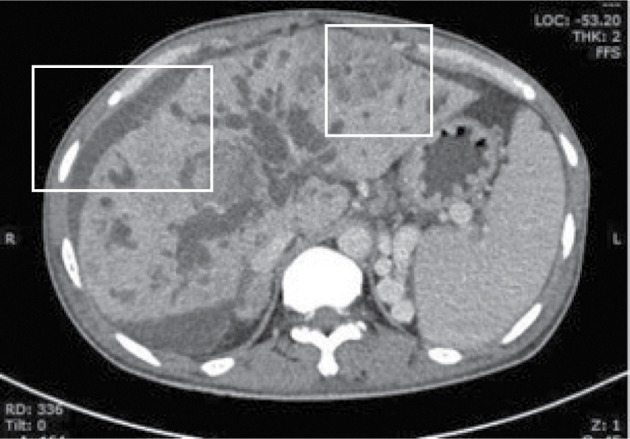

From 2001 to 2015, a total of 407 HCC patients underwent hepatic resection at the Hepatobiliary and Pancreas Unit, Department of Surgery, Chiang Mai University Hospital, Chiang Mai, Thailand. We reviewed the medical records of these 19 patients, and 4.7% were found to have v. The patients’ consent to review the medical record was requested, and all patient consents were received. The Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University Institutional Review Board, approved the study. Fifteen patients were male and four were female with the mean age of 51.1±11.5 years (range 35–76 years). The diagnosis of HCC with BDTT was made from the histopathological examination of the tumor thrombi in the 16 patients who had undergone curative hepatic resection (Figure 1) and two patients who had undergone palliative choledochotomy to remove BDTT with a biliary drainage procedure. Nonsurgical treatment was performed only in one patient who was initially diagnosed with HCC and BDTT from computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen (Figure 2), concurrent with the evidence of an elevated serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level >950 IU/mL.

Figure 1.

Macroscopic HCC with tumor thrombi in bile duct.

Abbreviation: HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma.

Figure 2.

Cirrhosis with ascites.

Notes: HCC at Segment (large square) 8 with diffuse dilation of bile duct and intraluminal tumor thrombus; HCC also seen at Segment 3 (small square). This patient underwent nonsurgical treatment.

Abbreviation: HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma.

Chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection plays an important role in HCC development in our patients and was present in 16 (84.2%) patients. Six patients received antiviral medication before surgery, and the remaining were treated after surgery. Two hepatitis C virus (HCV)-infected patients could not be treated with anti-HCV medication because of their health insurance coverage. The pathologically proven presence of cirrhosis was found in 12 (63.2%) patients. Serum AFP >20 ng/mL was present in 15 (78.9%) patients. The remaining patients had only epigastric pain (n = 3), right upper quadrant mass (n = 1), or were asymptomatic (n = 1). One patient had a history of preoperative transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) because initially he refused surgical treatment. The clinical and laboratory features of all 19 patients are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical features of 19 patients with HCC and BDTT

| Characteristics | Values, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Demographics (N = 19) | |

| Sex, male:female | 15:4 |

| Age (years) (mean±SD) | 51.1±11.5 |

| Background liver disease | |

| Chronic HBV infection | 16 (84.2%) |

| Chronic HCV infection | 1 (5.3%) |

| Chronic HBV and HCV co-infection | 1 (5.3%) |

| Non-viral (alcoholic) | 1 (5.3%) |

| Cirrhosis | 12 (63.2%) |

| Serum AFP | |

| >20 ng/mL | 15 (78.9%) |

| ≤20 ng/mL | 4 (21.1%) |

| Median (range), ng/mL | 347.4 (0.5–50000) |

| CA 19-9 | |

| Median (range), U/mL | 53.2 (2–2881) |

| Initial total bilirubin | |

| Median (range), mg/dL | 9.2 (0.5–26.3) |

| Medical history | |

| HIV Infection | 2 (10.5%) |

| Hypertension/dyslipidemia | 3 (15.8%) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 2 (10.5%) |

| Chronic alcohol drinking | 5 (26.3%) |

| Obstructive jaundice/cholangitis | |

| Presence | 14 (73.7%) |

| Absent | 5 (26.3%) |

| Biliary decompression | |

| PTBD | 4 (21.1%) |

| None | 14 (78.9%) |

| Preoperative HCC treatment | |

| TACE | 1 (5.3%) |

| None | 18 (94.7%) |

Abbreviations: HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; BDTT, bile duct tumor thrombus; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; CA, cancer antigen; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; PTBD, percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage; TACE, transcatheter arterial chemoembolization.

Diagnostic imaging procedures

The majority of the patients in the studied groups had official reports of ultrasonography (US) of the abdomen and contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen was performed in one patient with chronic renal insufficiency. The preoperative imaging studies of all patients were reviewed. Dilatations of the intrahepatic and/or extrahepatic bile ducts were seen in the imaging diagnosis of 18 (94.7%) patients with no occurrence of clinical jaundice in five patients. The tumor thrombus had approached to confluence of the bile duct in 14 (73.6%) patients. Seven patients also showed obvious dense tumor thrombus in the biliary tree. One case with bile duct obstruction at the confluence, with no obvious intrahepatic lesion and no rising of the serum AFP level, was misdiagnosed as hilar CCA. Only one patient had no occurrence of any preoperative jaundice or obstruction of bile duct from preoperative imaging, but diffuse biliary tumor thrombus was seen in the pathological result.

Operative strategies

Clinical obstructive jaundice or cholangitis accompanied the initial diagnosis in 14 (73.7%) patients. In our series, four (21.1%) patients achieved sufficient reduction of the jaundice preoperatively with percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD). No intervention for biliary decompression was performed for the remaining 15 (78.9%) patients because of the risk of bleeding from the drainage procedure. After evaluation of liver function, 18 of 19 patients underwent surgery without any appreciable morbidity or mortality.

Operative treatments for 16 patients consisted of a curative resection of the hepatic tumor. The operability rate during this study period was 84.2% (16 from 19). Removal of the BDTT occurred with hepatic resection in eight (50%) patients who underwent additional bile duct resection and biliary-enteric anastomosis. Four other (25%) patients underwent a choledochotomy to remove their BDTT. No additional procedures other than hepatectomy were required for four (25%) patients’ to achieve complete removal of the BDTT. Description of surgical procedures utilized in these 16 patients is shown in Table 2. In addition, intraoperatively, one patient was found to have intrahepatic metastasis at the contralateral lobe that was not detected from the preoperative CT of the abdomen and underwent a palliative R2 hepatic resection.

Table 2.

Extent of surgical procedures for HCC patients with BDTT

| Procedure | Values |

|---|---|

| Hepatectomy | |

| Right trisectionectomy + bile duct resection + caudate resection | 2 |

| Left trisectionectomy + bile duct resection + caudate resection | 1 |

| Right hepatectomy + bile duct resection | 1 |

| Left hepatectomy + bile duct resection | 4 |

| Right hepatectomy | 3 |

| Left hepatectomy + CBD exploration to remove BDTT | 4 |

| Left hepatectomy | 1 |

| BDTT removal | |

| CBD exploration to remove BDTT and palliative biliary drainage | 2 |

| No operation | 1 |

Abbreviations: HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; BDTT, bile duct tumor thrombus; CBD, common bile duct.

The remaining two patients received only a choledochotomy to remove the BDTT with palliative T-tube drainage or Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunal (HJ) anastomosis because their liver reserve and general condition could not tolerate the primary tumor resection. The pathological results of the tumor thrombus were HCC. Another patient presented with advanced disease with concurrent cirrhosis and received only palliative care followed by TACE.

Postoperative complications occurred in seven (38.9%) patients (Table 3). Severe complications (Clavien–Dindo grades III–V13) occurred in three patients, including acute renal failure requiring dialysis from day 1 to day 7 (grade IVa), intraabdominal collection requiring percutaneous drainage under local anesthesia by a radiological interventionist (grade IIIa), and transient reversible hepatic failure (grade IVa) with successfully conservative management (grade IVa). Mild complications (grades I–II13) occurred in four patients, and all were successful managed with medical or supportive treatments, including small surgical bed collection with wound infection (grade II), bile leak at hepaticojejunostomy anastomosis (grade II), and bilateral pleural effusion in two patients (grade I). All patients tolerated the operations without deaths from complications and were discharged from the hospital in good condition. The obstructive jaundice due to BDTT was successfully relieved in each patient.

Table 3.

Operative complications, postoperative recurrence, and survival details

| Variables | Values, n (fraction, %) |

|---|---|

| Inflow occlusion time (range), minutes | 10 (10–160) |

| Operating time (minutes) (mean±SD) | 415.6±170.0 |

| (Range) | (240–930) |

| Blood loss (range), mL | 1000 (100–5000) |

| Need PRC transfusions | 7 (38.9%) |

| Range of PRC transfusions (Unit) | 1–10 |

| Length of stay (days) (mean±SD) | 13±4.9 |

| Patient need for intensive care unit | 3 (16.7%) |

| Postoperative complications (Clavien-Dindo grade) | |

| No | 11 (61.1%) |

| I | 2 (2/18, 11.1%) |

| II | 2 (2/18, 11.1%) |

| IIIa | 1 (1/18, 5.6%) |

| Iva | 2 (2/18, 11.1%) |

| 3-month mortality | 0 (0/16) |

| 6-month DFS (%) | 11 (11/18, 61.1%) |

| HCC recurrence | |

| Within 6 months | 8 (8/18, 44.4%) |

| Within 1 year | 11 (11/18, 61.1%) |

| Pattern of recurrence | |

| Intrahepatic recurrence | 6 (54.5%) |

| Lymph node metastasis | 1 (9.0%) |

| Pulmonary metastasis | 3 (27.3%) |

| Peritoneal and bowel metastasis | 1 (9.0%) |

| Treatment after recurrence | |

| Metastectomy | 1 (1/11, 9.0%) |

| TACE/DEI | 6 (6/11, 54.5%) |

| Sorafinib | 2 (2/11, 18.2%) |

| Survival (n) | |

| >1 year | 12 (12/16, 75.0%) |

| >3 years | 6 |

| >5 years | 5 |

| >10 years | 1 |

| 3-year DFS, % (n) | 60.0% (6/10) |

| 3-year OS, % (n) | 60.0% (6/10) |

| Surgical curability from hepatic resection | |

| R0 | 11 (68.7%) |

| R1/R2 | 5 (31.3%) |

Abbreviations: DFS, disease-free survival; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; TACE, transcatheter arterial chemoembolization; DEI, direct ethanol injection; OS, overall survival; PRC, pack red cell.

Histopathological profiles

The pathological findings of the resected specimens are summarized in Table 4. The tumor diameters ranged from 2.2 to 19 cm (median 5.8 cm). The tumors were single nodular (n = 12), two contiguous nodules (n = 2), and satellite formation (n = 2). The pathologically proven presence of cirrhosis was found in 12 (63.2%) patients. Histologically, tumors were classified as well differentiated in four patients, moderately differentiated in nine, and poorly differentiated in three. Microscopic vascular invasion was found in 14 (87.5%) patients. Microscopic lymphatic invasion was found in two patients despite no detected intraoperative lymph node metastasis. Types of surgical resection after compatibility with pathological positive margins were R0 for eleven (68.7%) patients, R1 for four (25%) patients, and R2 for one (6.3%) patient.

Table 4.

Histopathological features and outcomes in 19 HCC patients with BDTT

| Patient No. | Age (years) | Sex | Cirrhosis | No. of tumors | Largest size (cm) | Diff. | Margin | V.inv | Lym/neu. Inv. | Recur. | Survival (months) | Outcome | Cause of death |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 51 | M | Present | 1 | 5 | Poor | Positive | (+) | (−) | IH, EH | 11 | Died | Cancer |

| 2 | 35 | M | Present | 1 | 6 | Moderate | Free | (+) | (−) | IH | 22 | Died | Cancer |

| 3 | 60 | M | Absent | 1 | 4 | Well | Free | (+) | (−) | (−) | 132 | Alive | – |

| 4 | 42 | M | Present | 1 | 6 | Moderate | Free | (+) | (−) | (−) | 104 | Alive | – |

| 5 | 76 | M | Absent | 1 | 2.5 | Moderate | Free | (+) | (−) | (−) | 84 | Alive | – |

| 6 | 57 | M | Present | 1 | 5.5 | Moderate | Free | (+) | (−) | (−) | 65 | Alive | – |

| 7 | 44 | M | Present | 3 | 3.5 | Well | Free | (+) | (−) | (−) | 60 | Alive | – |

| 8 | 39 | M | Present | 2 | 7.5 | Moderate | Positive | (−) | (+) | IH, EH | 17 | Died | Cancer |

| 9 | 46 | M | Absent | 1 | 8.5 | Poor | Free | (+) | (−) | (−) | 32 | Alive | – |

| 10 | 51 | M | Present | 1 | 7.5 | Poor | Positive | (+) | (−) | IH, EH | 4 | Died | Cancer |

| 11 | 55 | F | Absent | 1 | 19 | Moderate | Free | (+) | (+) | EH | 19 | Alive | – |

| 12 | 50 | M | Absent | 2 | 5 | Moderate | Positive | (+) | (−) | IH | 16 | Alive | – |

| 13 | 40 | F | Absent | 3 | 12 | Well | Positive | (+) | (−) | IH | 10 | Alive | – |

| 14 | 50 | M | Absent | 1 | 7.5 | Well | Free | (+) | (−) | IH | 11 | Alive | – |

| 15 | 74 | M | Present | 1 | 2.5 | Moderate | Free | (−) | (−) | EH | 7 | Alive | – |

| 16 | 47 | F | Present | 1 | 4 | Moderate | Free | (+) | (−) | (−) | 5 | Alive | – |

| 17 | 48 | M | Present | 1 | 5 | – | – | – | – | – | 2 | Died | Sepsis |

| 18 | 52 | F | Present | 1 | 5 | – | – | – | – | – | 2 | Died | Liver failure |

| 19 | 48 | M | Present | 1 | 2.2 | – | – | – | – | – | 7 | Alive | – |

Abbreviations: HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; BDTT, bile duct tumor thrombus; IH, intrahepatic recurrence; EH, extrahepatic recurrence; M, male; F, female; Diff., differentiared; V.inv, venous invasion; Lym/neu. inv., lymphatic/neural invasion; Recur, recurrence.

Apparent tumor growth in the bile duct from imaging was observed in three unresectable patients. Tumor thrombi were removed by the exploration of the common bile duct (CBD) in two patients, and viable tumor cells in the bile duct were confirmed histopathologically. The intrabiliary tumor thrombi were typically fragile with a grayish-white appearance and loosely attached to the ductal mucosa that could be easily removed from the lumen in our series.

Recurrence and survival time

Patients were followed up with US or CT abdomen at least every 3–6 months at our Outpatient Department, especially during the first 2 years. The follow-up study was conducted until February 2015 with a duration that ranged from 2 to 132 months. No patient was lost to follow-up, and all 19 patients were followed up regularly until death. In our series, there was no postoperative 3-month mortality from hepatic resection, and the 6-month disease-free survival was observed in eleven of 18 (61.1%) patients.

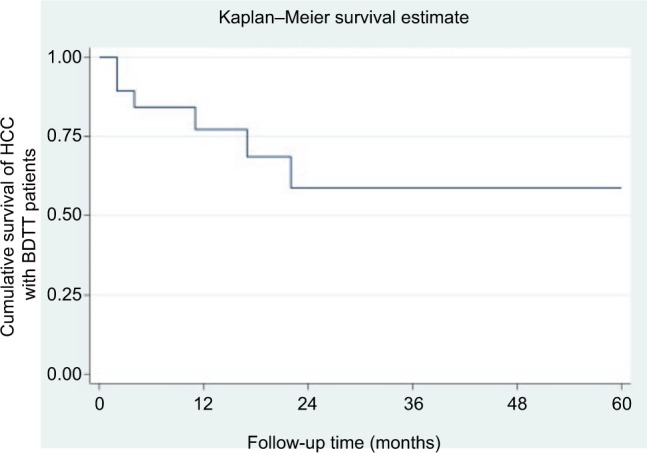

Twelve patients were followed up over 1 year with the 1-year survival rate of 75% (12/16). The patients who were followed up over 3 and 5 years were analyzed separately as a subgroup for survival. Their 3- and 5-year survival rates were 62.5% and 60%, respectively (Figure 3). Interestingly, there were five long-term survivors (≥5-year survival) whose longest disease-free survival time was >11 years. All of them were still alive up to the last follow-up visit without recurrence of cancer in our series.

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier survival analysis for 19 HCC cases with BDTT.

Abbreviations: HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; BDTT, bile duct tumor thrombus.

The survival times for the three patients who did not undergo liver resection or received only biliary decompression were only 2, 2, and 7 months, respectively.

Discussion

Jaundice was present in 19–40% of HCC patients at the time of diagnosis and was usually associated with advanced liver cirrhosis or extensive tumor infiltration.7,14–17 Obstructive jaundice caused due to BDTT in HCC patients is an uncommon feature, being identified in only 1–5% of patients treated operatively.4,18–21 The incidence in our series was 4.7%. HCC may involve the biliary tract in several different ways: tumor thrombosis, hemobilia, tumor compression, and diffuse tumor infiltration.16 As the incidence of HCC has increased, more details have been reported.22 This might be due to the improvement of diagnostic imaging strategies and more awareness toward the recognition of this condition.

Patients with HCC who manifested with obstructive jaundice from BDTT present difficult and challenging problems in differential diagnosis. A correct diagnosis of this group of patients is important, because surgical treatment may be beneficial with favorable long-term results.4,8,9,16,23–25 On the contrary, there was no chance of palliation or possible cure in patients with advanced tumor infiltration or progressive terminal liver failure. In our series, corrected preoperative diagnosis as having HCC obstructing the bile duct was high (in almost all patients, 17 of 19 patients), and only one patient was misdiagnosed as hilar CCA, and in another patient, the BDTT diagnosis was determined from the pathological result because there was no suspicious bile duct dilatation from the preoperative CT of the abdomen.

Curative resection of the tumor improved the outcomes of this type of disease in some previous reports.8,26–31 Either preoperative PTBD or endoscopic biliary drainage can be chosen to relieve jaundice with similar procedure-related risk.32–34 Preoperative PTBD was performed in five patients without any PTBD-related complications, in our series. Chen et al4 previously reported their experience with 20 HCC patients with BDTT that caused jaundice, in which only two (10%) patients underwent liver resection. Similarly, Lau et al27 reported a low resectability rate of 18% (2/11). This might be attributed to poor hepatic reserve caused by underlying cirrhosis and obstructive jaundice. In our study, however, 15 of 19 (78.9%) patients underwent a hepatectomy with curative aim and one of 19 patients for palliative aim after appropriate preoperative management, regardless of whether jaundice was present. So, carefully evaluating patient’s liver function and future liver remnant were important keys of successful management in HCC with BDTT patients, which could achieve a high rate of R0 resection in 11/16 (68.7%) patients. These results would emphasize that biliary tumor thrombi from HCC were not necessarily a contraindication for hepatectomy and do not imply advanced disease.

Intrahepatic metastasis by spreading via the portal vein route was an important mechanism of recurrence. Overall recurrence after hepatectomy occurred in more than half (9/16, 56.3%) of our patients and all with early recurrence within 1 year. Recurrence in one patient was bile duct-related and manifested another episode of obstructive jaundice. Cancer recurring at the choledochotomy site or intraoperative implantation appeared to be the likely cause of this condition. Interestingly, there was one patient without portal vein or microscopic venous invasion who also developed both intrahepatic recurrence and pulmonary metastasis. Therefore, this finding implied that HCC invading through the bile duct may have another route of intrahepatic and distant metastasis. A similar result was previously reported by Ikenaga et al.11 TACE, direct ethanol injection (DEI), sorafinib, or metastectomy in selective patients are well-established treatments for recurrent intrahepatic HCC and distant metastasis. The pattern of recurrence and modality of treatment after recurrence are shown in Table 3.

In our series, the postoperative 1-year survival rate of patients was 75.0% with a 1-year disease-free survival rate of 43.8%. These are better than that of a previous report from Qin et al.3 All the five long-term survivors (≥5-year survival) received a major liver resection (hemihepatectomy and/or bile duct resection) with the longest disease-free survival of >11 years in one patient. This might be attributed to appropriate treatment. In HCC patients with BDTT, shorter survival may be associated with venous or lymphatic invasion, positive margin, poorly differentiated tumor, as well as underlying liver cirrhosis and advanced tumor stage.

Conclusion

Obstructive jaundice due to biliary thrombus in HCC patients is an uncommon feature but must be kept in mind as one of several differential diagnoses. Bile duct obstruction from tumor thrombus is not necessarily a contraindication for surgery and does not imply advanced disease. Identification of this group of patients is clinically important, because if the appropriate operation is selected, it can offer an opportunity for cure and favorable long-term survival.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Huang JF, Wang LY, Lin ZY, et al. Incidence and clinical outcome of icteric type hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17(2):190–195. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2002.02677.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kojiro M, Kawabata K, Kawano Y, Shirai F, Takemoto N, Nakashima T. Hepatocellular carcinoma presenting as intrabile duct tumor growth: a clinicopathologic study of 24 cases. Cancer. 1982;49(10):2144–2147. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19820515)49:10<2144::aid-cncr2820491026>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qin LX, Ma ZC, Wu ZQ, et al. Diagnosis and surgical treatments of hepatocellular carcinoma with tumor thrombosis in bile duct: experience of 34 patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10(10):1397–1401. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i10.1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen MF, Jan YY, Jeng LB, Hwang TL, Wang CS, Chen SC. Obstructive jaundice secondary to ruptured hepatocellular carcinoma into the common bile duct. Surgical experiences of 20 cases. Cancer. 1994;73(5):1335–1340. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940301)73:5<1335::aid-cncr2820730505>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Gaetano AM, Nure E, Grossi U, et al. Fibrolamellar hepatocellular carcinoma with biliary tumor thrombus: an unreported association. Jpn J Radiol. 2013;31(10):706–712. doi: 10.1007/s11604-013-0233-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sasaki T, Takahara N, Kawaguchi Y, et al. Biliary tumor thrombus of hepatocellular carcinoma containing lipiodol mimicking a calcified bile duct stone. Endoscopy. 2012;44(suppl 2 UCTN):E250–E251. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1309761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ise N, Andoh H, Sato T, Yasui O, Kurokawa T, Kotanagi H. Three cases of small hepatocellular carcinoma presenting as obstructive jaundice. HPB (Oxford) 2004;6(1):21–24. doi: 10.1080/13651820310017129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shiomi M, Kamiya J, Nagino M, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma with biliary tumor thrombi: aggressive operative approach after appropriate preoperative management. Surgery. 2001;129(6):692–698. doi: 10.1067/msy.2001.113889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Satoh S, Ikai I, Honda G, et al. Clinicopathologic evaluation of hepatocellular carcinoma with bile duct thrombi. Surgery. 2000;128(5):779–783. doi: 10.1067/msy.2000.108659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yeh CN, Jan YY, Lee WC, Chen MF. Hepatic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma with obstructive jaundice due to biliary tumor thrombi. World J Surg. 2004;28(5):471–475. doi: 10.1007/s00268-004-7185-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ikenaga N, Chijiiwa K, Otani K, Ohuchida J, Uchiyama S, Kondo K. Clinicopathologic characteristics of hepatocellular carcinoma with bile duct invasion. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13(3):492–497. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0751-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Cancer Institute DoMS, Ministry of Public Health, Thailand 2016 [homepage on the Internet] [Accessed February 10, 2017]. Available from: http://nci.go.th/

- 13.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240(2):205–213. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fan ST, Lai EC, Lo CM, Ng IO, Wong J. Hospital mortality of major hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma associated with cirrhosis. Arch Surg. 1995;130(2):198–203. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1995.01430020088017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee NW, Wong KP, Siu KF, Wong J. Cholangiography in hepatocellular carcinoma with obstructive jaundice. Clin Radiol. 1984;35(2):119–123. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(84)80008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qin LX, Tang ZY. Hepatocellular carcinoma with obstructive jaundice: diagnosis, treatment and prognosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9(3):385–391. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i3.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakashima T, Okuda K, Kojiro M, et al. Pathology of hepatocellular carcinoma in Japan. 232 consecutive cases autopsied in ten years. Cancer. 1983;51(5):863–877. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19830301)51:5<863::aid-cncr2820510520>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ueda M, Takeuchi T, Takayasu T, et al. Classification and surgical treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) with bile duct thrombi. Hepatogastroenterology. 1994;41(4):349–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ikeda Y, Matsumata T, Adachi E, Hayashi H, Takenaka K, Sugimachi K. Hepatocellular carcinoma of the intrabiliary growth type. Int Surg. 1997;82(1):76–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mok KT, Chang HT, Liu SI, Jou NW, Tsai CC, Wang BW. Surgical treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma with biliary tumor thrombi. Int Surg. 1996;81(3):284–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang HJ, Kim JH, Kim JH, Kim WH, Kim MW. Hepatocellular carcinoma with tumor thrombi in the bile duct. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46(28):2495–2499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spahr L, Frossard JL, Felley C, Brundler MA, Majno PE, Hadengue A. Biliary migration of hepatocellular carcinoma fragment after transcatheter arterial chemoembolization therapy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;12(2):243–244. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200012020-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moon DB, Hwang S, Wang HJ, et al. Surgical outcomes of hepatocellular carcinoma with bile duct tumor thrombus: a Korean multicenter study. World J Surg. 2013;37(2):443–451. doi: 10.1007/s00268-012-1845-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peng SY, Wang JW, Liu YB, et al. Surgical intervention for obstructive jaundice due to biliary tumor thrombus in hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Surg. 2004;28(1):43–46. doi: 10.1007/s00268-003-7079-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qiao W, Yu F, Wu L, Li B, Zhou Y. Surgical outcomes of hepatocellular carcinoma with biliary tumor thrombus: a systematic review. BMC Gastroenterol. 2016;16:11. doi: 10.1186/s12876-016-0427-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lau WY, Leung JW, Li AK. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma presenting as obstructive jaundice. Am J Surg. 1990;160(3):280–282. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(06)80023-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lau W, Leung K, Leung TW, et al. A logical approach to hepatocellular carcinoma presenting with jaundice. Ann Surg. 1997;225(3):281–285. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199703000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu CS, Wu SS, Chen PC, et al. Cholangiography of icteric type hepatoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89(5):774–777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jan YY, Chen MF, Chen TJ. Long term survival after obstruction of the common bile duct by ductal hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Surg. 1995;161(10):771–774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shimada M, Takenaka K, Hasegawa H, et al. Hepatic resection for icteric type hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 1997;44(17):1432–1437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tada K, Kubota K, Sano K, et al. Surgery of icteric-type hepatoma after biliary drainage and transcatheter arterial embolization. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46(26):843–848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Matsueda K, Yamamoto H, Umeoka F, et al. Effectiveness of endoscopic biliary drainage for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma associated with obstructive jaundice. J Gastroenterol. 2001;36(3):173–180. doi: 10.1007/s005350170125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee JW, Han JK, Kim TK, et al. Obstructive jaundice in hepatocellular carcinoma: response after percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage and prognostic factors. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2002;25(3):176–179. doi: 10.1007/s00270-001-0100-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakayama T, Ikeda A, Okuda K. Percutaneous transhepatic drainage of the biliary tract: technique and results in 104 cases. Gastroenterology. 1978;74(3):554–559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]