The lipid droplet phospholipase Lpl1 is identified as a novel component of the proteotoxic stress response mediated by Rpn4. Lpl1 regulates both protein degradation and lipid droplet homeostasis. These results suggest that dynamic regulation of lipid droplets may be an important aspect of the cellular response to misfolded proteins.

Abstract

Protein misfolding is toxic to cells and is believed to underlie many human diseases, including many neurodegenerative diseases. Accordingly, cells have developed stress responses to deal with misfolded proteins. The transcription factor Rpn4 mediates one such response and is best known for regulating the abundance of the proteasome, the complex multisubunit protease that destroys proteins. Here we identify Lpl1 as an unexpected target of the Rpn4 response. Lpl1 is a phospholipase and a component of the lipid droplet. Lpl1 has dual functions: it is required for both efficient proteasome-mediated protein degradation and the dynamic regulation of lipid droplets. Lpl1 shows a synthetic genetic interaction with Hac1, the master regulator of a second proteotoxic stress response, the unfolded protein response (UPR). The UPR has long been known to regulate phospholipid metabolism, and Lpl1's relationship with Hac1 appears to reflect Hac1's role in stimulating phospholipid synthesis under stress. Thus two distinct proteotoxic stress responses control phospholipid metabolism. Furthermore, these results provide a direct link between the lipid droplet and proteasomal protein degradation and suggest that dynamic regulation of lipid droplets is a key aspect of some proteotoxic stress responses.

INTRODUCTION

Misfolded proteins are toxic to cells and are believed to cause or contribute to many human diseases, including most neurodegenerative diseases (Hipp et al., 2014). Accordingly, cells have developed stress responses to identify and destroy misfolded proteins. Two important such pathways are the unfolded protein response (UPR) and the Rpn4 response (Xie and Varshavsky, 2001; Walter and Ron, 2011). The UPR senses misfolded proteins within the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and responds in a complex manner to mitigate this threat. Central to this response is the activation of the transcription factor Hac1, which mediates a broad transcriptional program to remodel the cell and allow it to better address the proteotoxic threat (Travers et al., 2000). This includes transcription of ER chaperones to promote protein folding, as well as the machinery involved in ER-associated degradation (ERAD) to destroy those proteins that cannot be refolded. The UPR is also capable of down-regulating protein synthesis and, in higher organisms, initiating apoptosis, the latter pathway likely reserved for the most severe cases of proteotoxic stress (Kaufman, 1999; Walter and Ron, 2011). Of interest, for reasons that are not entirely clear, the UPR also stimulates the synthesis of phospholipids (Carman and Han, 2011)

The transcription factor Rpn4 mediates a second proteotoxic stress response that is believed to monitor the functional capacity of the proteasome—the large multisubunit protease that is responsible for most selective protein degradation in eukaryotes (Xie and Varshavsky, 2001). Rpn4 recognizes a consensus motif in the promoters of all known proteasome subunits (Mannhaupt et al., 1999), allowing Rpn4 to orchestrate new proteasome synthesis in a concerted stoichiometric manner. However, Rpn4 is also a substrate of the proteasome with an extremely short half-life (Xie and Varshavsky, 2001). Under conditions that compromise or overwhelm proteasome function, Rpn4 is stabilized. This results in new proteasome synthesis, increasing degradative capacity and eventually restoring rapid degradation of Rpn4, which normalizes the stress response. This pathway appears to be functionally conserved in higher organisms, where it is mediated by the transcription factor Nrf1 (Radhakrishnan et al., 2010; Steffen et al., 2010).

The lipid droplet is an organelle-like structure that houses large quantities of neutral lipids (mainly triacylglycerols and sterol esters) and is bounded by a phospholipid monolayer (Radulovic et al., 2013; Wang, 2015). One function of the lipid droplet is believed to be in metabolism—storing and releasing these neutral lipids as needed to meet the cell's energy requirements (Radulovic et al., 2013). However, the lipid droplet remains poorly understood. It has become apparent that the lipid droplet has its own dedicated and complex proteome (Binns et al., 2006). In addition, lipid droplets appear to be dynamic, capable of changing in size and number under different cellular conditions (Fei et al., 2008, 2011). Here we identify the lipid droplet phospholipase Lpl1 as a component of the Rpn4 proteotoxic stress response. Loss of Lpl1 results in multiple proteolytic defects, including synthetic genetic interactions with members of the unfolded protein response. These defects are accompanied by alterations in lipid droplet homeostasis. These results suggest an important role for the lipid droplet in proteotoxic stress responses and provide a direct mechanistic link between these seemingly unrelated pathways.

RESULTS

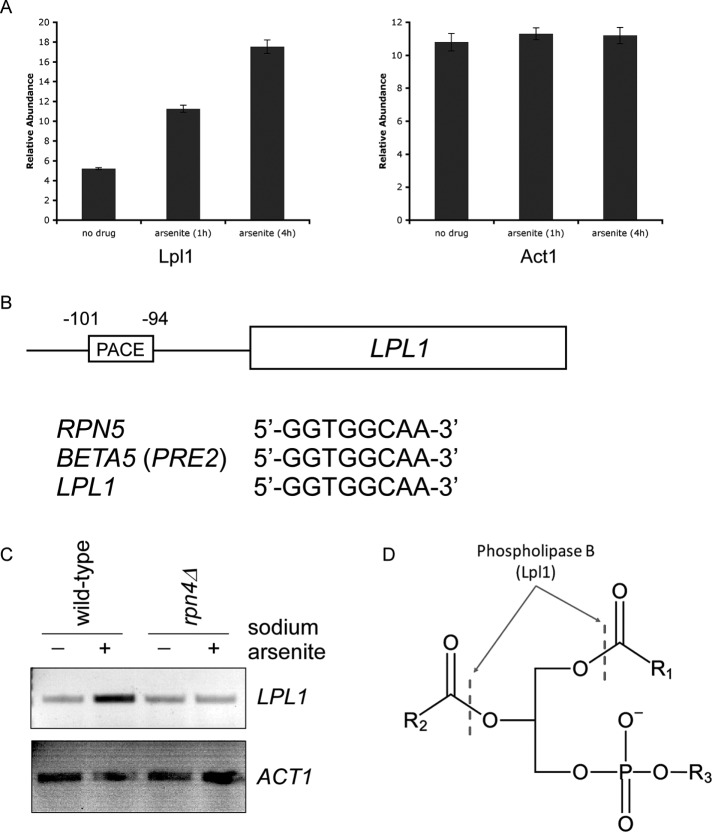

Lpl1 is a target of the Rpn4 proteotoxic stress response

We recently carried out a proteomic analysis of the cellular response to trivalent arsenic in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Guerra-Moreno et al., 2015). Under these conditions, Rpn4 protein levels are increased by ∼20-fold, and this results in a corresponding increase in the abundance of proteasome subunits. Among the nearly 4600 proteins for which data were available, we noticed that the protein Lpl1 was strongly induced by arsenic in a manner that was similar to some Rpn4 targets (Figure 1A). Rpn4 recognizes its targets through a consensus motif in their promoters known as the proteasome-associated control element (PACE; Mannhaupt et al., 1999). We identified a canonical PACE motif within the LPL1 promoter that was identical to that of established Rpn4 targets such as Rpn5 and Beta5 (Pre2; Figure 1B). Furthermore, Lpl1's PACE motif was situated within the first 200 nucleotides preceding the start codon, which is the typical location (Leggett et al., 2002). To test directly whether LPL1 was a transcriptional target of Rpn4, we performed reverse-transcription PCR (RT-PCR) under the same conditions as in Figure 1A. LPL1 was strongly induced at the RNA level, and this induction was largely dependent on Rpn4 (Figure 1C). Thus Lpl1 is a target of the Rpn4 proteotoxic stress response.

FIGURE 1:

Lpl1 is regulated by Rpn4. (A) Relative protein abundance of Lpl1 at 0, 1, and 4 h after treatment with sodium arsenite (1 mM). Data were generated using a tandem mass tag-based mass spectrometry approach (Guerra-Moreno et al., 2015). Act1, a control protein, showed no change. Error bars represent SDs from triplicate cultures. In addition, differences between untreated and treated samples were statistically significant by Student's t test (p < 0.01) for Lpl1 but not Act1. (B) Schematic diagram of the LPL1 gene with its associated 5′-untranslated region. A classical PACE motif is present, with its location indicated relative to the start codon. This PACE motif is identical to that of other well-established Rpn4 targets, such as Rpn5 and Beta5 (Pre2). (C) Stress-inducible transcription of LPL1 in wild-type and rpn4Δ cells, as determined by RT-PCR. Treatment was with sodium arsenite (1 mM) for 1 h. ACT1 (bottom) serves as a control. (D) Schematic of a generic phospholipid with the cleavage sites indicated for type B phospholipases such as Lpl1. R1 and R2, fatty acyl groups; R3, polar head group (e.g., choline, ethanolamine, serine, inositol).

Whereas most known targets of Rpn4 are proteasome subunits or proteasome-interacting proteins, Lpl1 is a component of the lipid droplet (Selvaraju et al., 2014). By sequence and functional analysis, it is a type B phospholipase, allowing it to cleave phospholipids at the sn-1 and sn-2 positions, releasing free fatty acids from the three-carbon backbone, which retains its polar head group (Figure 1D; Selvaraju et al., 2014). Lpl1 showed a relatively broad substrate specificity in vitro, acting on major species such as phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylcholine, and phosphatidylserine, although it showed much lower activity against phosphatidylinositol (Selvaraju et al., 2014).

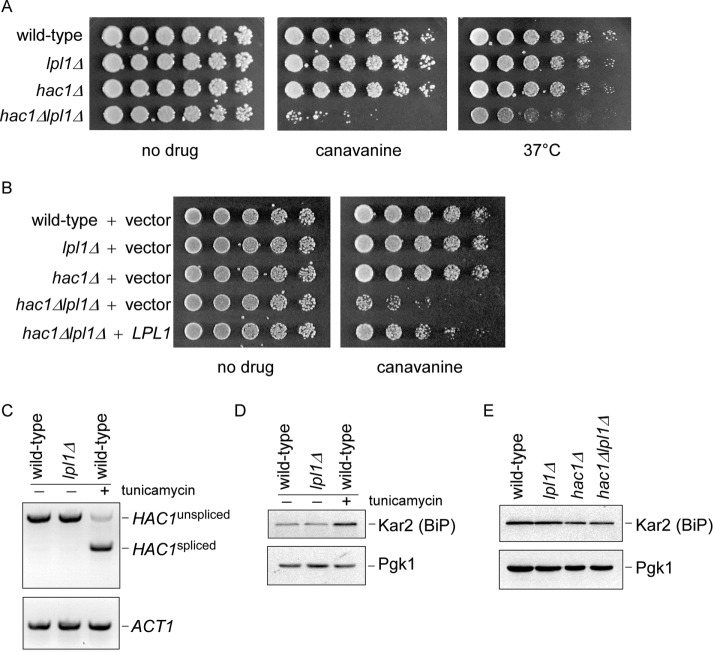

Functional relationship between Lpl1 and the unfolded protein response

Control of Lpl1 by Rpn4 suggested a potential role for Lpl1 in protein degradation. We examined the lpl1Δ mutant for growth defects after exposure to various proteotoxic stresses but were unable to identify a phenotype (unpublished data). However, when LPL1 was deleted in a hac1Δ background, we observed robust phenotypes in response to multiple causes of proteotoxic stress, including elevated temperature and the abnormal amino acid canavanine, which is incorporated into nascent proteins, causing them to misfold (Figure 2A). Hac1 is a transcription factor and a master regulator of the UPR, which is distinct from the Rpn4 response. The UPR responds specifically to misfolded proteins within the ER, and Hac1 orchestrates a complex transcriptional response to mitigate this threat (Travers et al., 2000; Wu et al., 2014). The hac1Δlpl1Δ phenotype could be complemented by restoration of plasmid-derived LPL1, confirming that the phenotype was indeed caused by loss of Lpl1 (Figure 2B). One potential explanation for such a synthetic phenotype is that the UPR is constitutively induced in the lpl1Δ mutant, compensating for defects in this mutant. Hac1 is activated by splicing of its mRNA (Wu et al., 2014). We saw no evidence of increased HAC1 splicing in the lpl1Δ mutant by RT-PCR (Figure 2C). Similarly, the classical UPR target Kar2 (the yeast orthologue of BiP) was not up-regulated at the protein level in the lpl1Δ mutant (Figure 2D), although its levels were slightly decreased in the absence of Hac1, as expected (Figure 2E).

FIGURE 2:

Proteotoxic phenotypes of the hac1Δlpl1Δ mutant. (A) Growth of wild-type, lpl1Δ, hac1Δ, and hac1Δlpl1Δ strains in the presence of canavanine (1.5 µg/ml) or at elevated temperature, as indicated. Cells were spotted in threefold serial dilutions and cultured for 2–4 d. (B) Growth of wild-type, lpl1Δ, hac1Δ, and hac1Δlpl1Δ strains expressing an empty vector and hac1Δlpl1Δ expressing LPL1 in the presence or absence of canavanine (1.5 µg/ml), as indicated. Cells were spotted in threefold serial dilutions and cultured for 2–4 d at 30°C. (C) Splicing of HAC1, as determined by RT-PCR, in wild-type and lpl1Δ strains. A wild-type strain treated with tunicamycin (5 µg/ml), an inducer of the unfolded protein response, serves as a positive control. ACT1 (bottom) serves as a control. (D) Kar2 protein levels in whole-cell extracts of wild-type and lpl1Δ strains, as determined by SDS–PAGE followed by immunoblot with anti-Kar2 antibody (top) or anti-Pgk1 antibody (bottom; loading control). (E) Kar2 protein levels in wild-type, lpl1Δ, hac1Δ, and hac1Δlpl1Δ strains. Exponential-phase cells cultured in synthetic medium were treated at 37°C for 1 h. Whole-cell extracts were prepared and analyzed by SDS–PAGE followed by immunoblot with anti-Kar2 antibody (top) or anti-Pgk1 antibody (bottom; loading control).

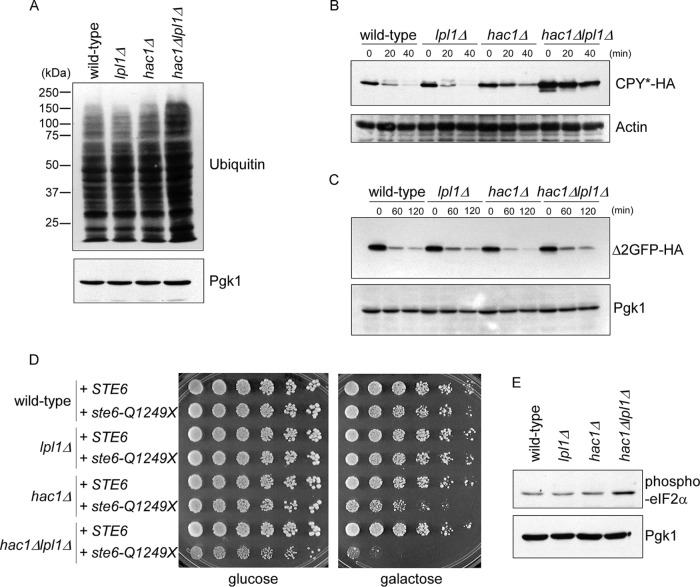

Lpl1 functions in protein degradation

The preceding regulatory and phenotypic data suggest a role for Lpl1 in proteasome-mediated protein degradation. Because proteasomes preferentially destroy ubiquitinated proteins, defects in the pathway may lead to an accumulation of high–molecular weight ubiquitin immunoreactive material. Indeed, we observed an accumulation of these ubiquitinated species in the hac1Δlpl1Δ mutant, consistent with a significant protein degradation defect (Figure 3A). We next examined a specific protein, CPY*, which is a classical substrate of the ERAD pathway. Wild-type and lpl1Δ cells showed similarly rapid degradation of this substrate, with a half-life of <20 min (Figure 3B). CPY* degradation was attenuated in the hac1Δ mutant, as expected. Turnover of CPY*, however, was much more strongly attenuated in the hac1Δlpl1Δ mutant, which was reflected not only in the rate of turnover, but also in the elevation of steady-state CPY* levels (Figure 3B). This elevation of steady-state protein levels reflects the fact that in a cycloheximide chase assay, where there is no pulse period, the zero time point represents steady-state protein abundance. Thus steady-state levels may increase if there is a strong enough degradative defect or even decrease if there is a strong degradative advantage (Hanna et al., 2006; Guerra-Moreno and Hanna, 2016; Shi et al., 2016). To determine whether this effect was specific to ERAD substrates, we looked at a model cytoplasmic substrate of the proteasome, Δ2-GFP (Kruegel et al., 2011), under similar conditions. This substrate also showed a high rate of degradation, but we did not detect any stabilization in the lpl1Δ, hac1Δ, or hac1Δlpl1Δ mutant (Figure 3C).

FIGURE 3:

Protein degradation defects in the hac1Δlpl1Δ mutant. (A) Levels of ubiquitin conjugates in whole-cell extracts of wild-type, lpl1Δ, hac1Δ, and hac1Δlpl1Δ strains, as determined by SDS–PAGE followed by immunoblot with anti-ubiquitin antibody (top) or anti-Pgk1 antibody (bottom; loading control). Experiment was performed at 37°C. (B) Cycloheximide chase analysis of CPY* turnover in wild-type, lpl1Δ, hac1Δ, and hac1Δlpl1Δ strains, as determined by SDS–PAGE followed by immunoblot with anti-HA antibody (top) or anti-actin antibody (bottom; loading control). Experiment was performed at 37°C. See Supplemental Figure S1 for quantitation. (C) Cycloheximide chase analysis of turnover of the cytoplasmic proteasome substrate Δ2-GFP, as determined by SDS–PAGE followed by immunoblot with anti-HA antibody (top) or anti-Pgk1 antibody (bottom; loading control). Experiment was performed at 37°C. (D) Growth of wild-type, lpl1Δ, hac1Δ, and hac1Δlpl1Δ strains expressing galactose-inducible wild-type STE6 or the misfolded mutant ste6-Q1249X. Cells were spotted in threefold serial dilutions and cultured for 4 d at 35°C. (E) Levels of phosphorylated eIF2α (Ser-51) in whole-cell extracts of wild-type, lpl1Δ, hac1Δ, and hac1Δlpl1Δ strains treated with sodium arsenite (0.2 mM), as determined by SDS–PAGE followed by immunoblot with anti–phospho-eIF2α antibody (top) or anti-Pgk1 antibody (bottom; loading control). Experiment was performed at 37°C.

Multiple classes of ERAD substrates have been identified, including ER lumenal substrates (such as CPY*) and ER membrane substrates. The 12-transmembrane-domain protein Ste6 is a classical and robust ERAD substrate. In wild-type cells, expression of mutant Ste6 does not produce a growth defect, as these cells can rapidly destroy misfolded Ste6 (Metzger and Michaelis, 2009). However, mutants defective in Ste6 degradation show growth defects that reflect the underlying toxicity of this misfolded protein. We expressed mutant ste6-Q1249X in these strains, along with wild-type Ste6 as a control. Wild-type and lpl1Δ cells showed no defect (Figure 3D). By contrast, the hac1Δ mutant showed a growth defect, consistent with a defect in Ste6 degradation. Again, this defect was dramatically exacerbated in the hac1Δlpl1Δ double mutant (Figure 3D). One useful aspect of this assay is that it integrates specific degradation defects with an in vivo readout of physiological relevance.

A hallmark of many proteotoxic stressors is the phosphorylation of the translation initiation factor eIF2α at serine-51, a pathway referred to as the integrated stress response (Kaufman, 1999). This phosphorylation inhibits eIF2 function, thereby limiting protein synthesis by the ribosome. Under conditions in which protein misfolding is prevalent, reducing the synthesis of new proteins may be advantageous. The UPR, for example, has long been known to promote eIF2α phosphorylation (Kaufman, 1999). We recently showed that trivalent arsenic is a potent inducer of eIF2α phosphorylation in yeast (Guerra-Moreno et al., 2015), although the underlying mechanism is unknown. We monitored eIF2α phosphorylation in these strains after arsenic treatment. The hac1Δlpl1Δ mutant showed increased levels of eIF2α phosphorylation (Figure 3E), compatible with an underlying defect in proteotoxic stress response in this mutant. Taken together, these data suggest an important role for Lpl1 in quality control protein degradation by the proteasome.

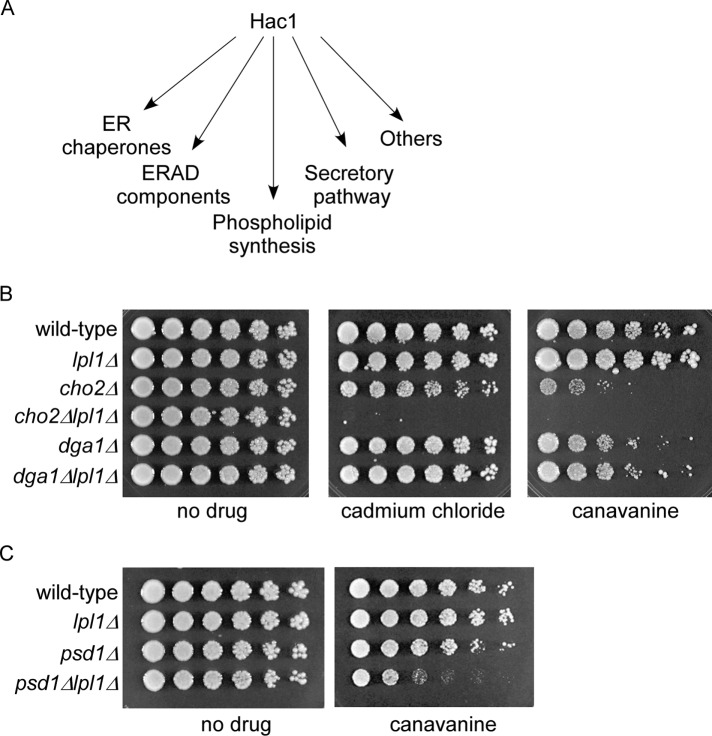

Relationship between Lpl1 and phospholipid metabolism

To obtain a better understanding of the role of Lpl1 in protein degradation, we sought to understand the basis for the relationship between Lpl1 and Hac1. According to microarray and other analyses, the UPR and Hac1 have potentially hundreds of transcriptional targets (Travers et al., 2000). These targets fall into a smaller number of categories, including ER chaperones, dedicated ERAD components, secretory pathway genes, phospholipid metabolism genes, and others (Figure 4A). Control of phospholipid synthesis by the UPR has been recognized for almost 20 years (Cox et al., 1997; Kaufman, 1999), although its precise role in counteracting proteotoxic stress has remained somewhat unclear. Naturally, this aspect of the UPR was intriguing, given that Lpl1 also functions in phospholipid metabolism. The Hac1 target Cho2 promotes synthesis of phosphatidylcholine, an abundant membrane phospholipid, from phosphatidylethanolamine. We constructed a cho2Δlpl1Δ double mutant and tested its ability to survive various proteotoxic stressors. The cho2Δlpl1Δ mutant showed strong sensitivities to canavanine, phenocopying the hac1Δlpl1Δ mutant (Figure 4B). We also detected a strong growth defect of cho2Δlpl1Δ on cadmium chloride, a divalent heavy metal and another well-established cause of proteotoxicity (Seufert and Jentsch, 1990). To gauge the specificity of this interaction, we looked at Dga1, which is also involved in lipid metabolism but functions in the unrelated triacylglycerol synthesis pathway and is not a known target of the UPR. In contrast, a dga1Δlpl1Δ mutant showed no effect under these conditions (Figure 4B). It is worth noting that the cho2Δ mutant alone showed sensitivity under these conditions, suggesting some degree of proteotoxic stress defect on its own (Figure 4B; see also Thibault et al., 2012).

FIGURE 4:

Proteotoxic phenotypes of cho2Δlpl1Δ and psd1Δlpl1Δ mutants. (A) Major classes of transcriptional targets for Hac1. (B) Growth of wild-type, lpl1Δ, cho2Δ, cho2Δlpl1Δ, dga1Δ, and dga1Δlpl1Δ strains in the presence of cadmium chloride (30 µM) or canavanine (1.5 µg/ml), as indicated. Cells were spotted in threefold serial dilutions and cultured at 30°C for 2–9 d. (C) Growth of wild-type, lpl1Δ, psd1Δ, and psd1Δlpl1Δ strains in the presence or absence of canavanine (1.5 µg/ml), as indicated. Cells were spotted in threefold serial dilutions and cultured at 30°C for 2–4 d.

Psd1 functions upstream of Cho2, promoting conversion of phosphatidylserine to phosphatidylethanolamine. We tested a psd1Δlpl1Δ mutant, which also showed a growth defect when treated with canavanine (Figure 4C), although the severity of the phenotype was less than that of cho2Δlpl1Δ. We did not detect synthetic genetic effects when lpl1Δ was combined with other mutants of the UPR such as Hrd1, a core component of the ERAD pathway, or Ino1, which mediates phosphatidylinositol synthesis via a metabolic pathway distinct from that which synthesizes phosphatidylserine, phosphatidylethanolamine, and phosphatidylcholine (unpublished data).

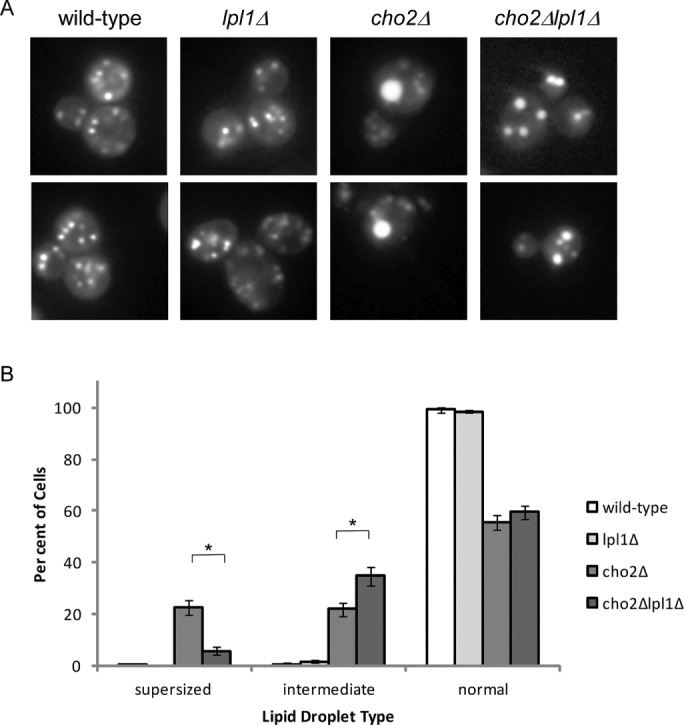

Modulation of lipid droplet dynamics by Lpl1

Lipid droplets are small, organelle-like structures in which a phospholipid monolayer surrounds a core of mostly neutral lipids, principally triacylglycerols and sterol esters. They can be visualized using fluorescence microscopy (Thibault et al., 2012; Selvaraju et al., 2014). In wild-type cells under normal conditions, there are typically 5–10 distinct lipid droplets per cell, and these are small and uniform in size. cho2Δ cells show extremely large lipid droplets, which can be up to 50 times the volume of wild-type lipid droplets (Fei et al., 2011). These cells also have many fewer lipid droplets and, in many cases, only a single dominant lipid droplet.

We confirmed the finding of supersized lipid droplets in cho2Δ cells (Figure 5A), which frequently showed a single massive lipid droplet, with few or no accompanying smaller lipid droplets. This type of lipid droplet was virtually never seen in wild-type cells. The lpl1Δ mutant appeared similar to wild type. However, loss of Lpl1 in the cho2Δ background markedly altered the lipid droplet profile (Figure 5, A and B). The number of cells with a single dominant lipid droplet was reduced. In their place were cells with lipid droplets that were greater in number but smaller in size than the supersized lipid droplets of cho2Δ (Figure 5, A and B). Because these lipid droplets were still larger than those seen in wild-type cells, we referred to this pattern as “intermediate.” It is worth noting that such intermediate-type cells can be seen in the cho2Δ mutant (see also Fei et al., 2011), but their abundance is significantly increased upon loss of Lpl1. These findings indicate that Lpl1 functions in the dynamic regulation of lipid droplets. Furthermore, the partial restoration of the cho2Δ phenotype suggests that Lpl1 may be required for the formation of supersized lipid droplets in the cho2Δ mutant.

FIGURE 5:

Lpl1 affects lipid droplet dynamics. (A) Representative images of lipid droplets, as visualized by fluorescence microscopy for the indicated strains. cho2Δ cells show a relative accumulation of cells with a single very large (“supersized”) lipid droplet. cho2Δlpl1Δ cells show a relative accumulation of cells with an intermediate phenotype (i.e., lipid droplets that are smaller but more numerous than those seen in cho2Δ). (B) Quantitation of normal, intermediate, and supersized lipid droplets. Six hundred cells were counted (in 100 cell groups) for each strain. Error bars represent SDs. Asterisk, statistically significant by Student's t test (p < 0.001).

Relationship between Rpn4 and phospholipid metabolism

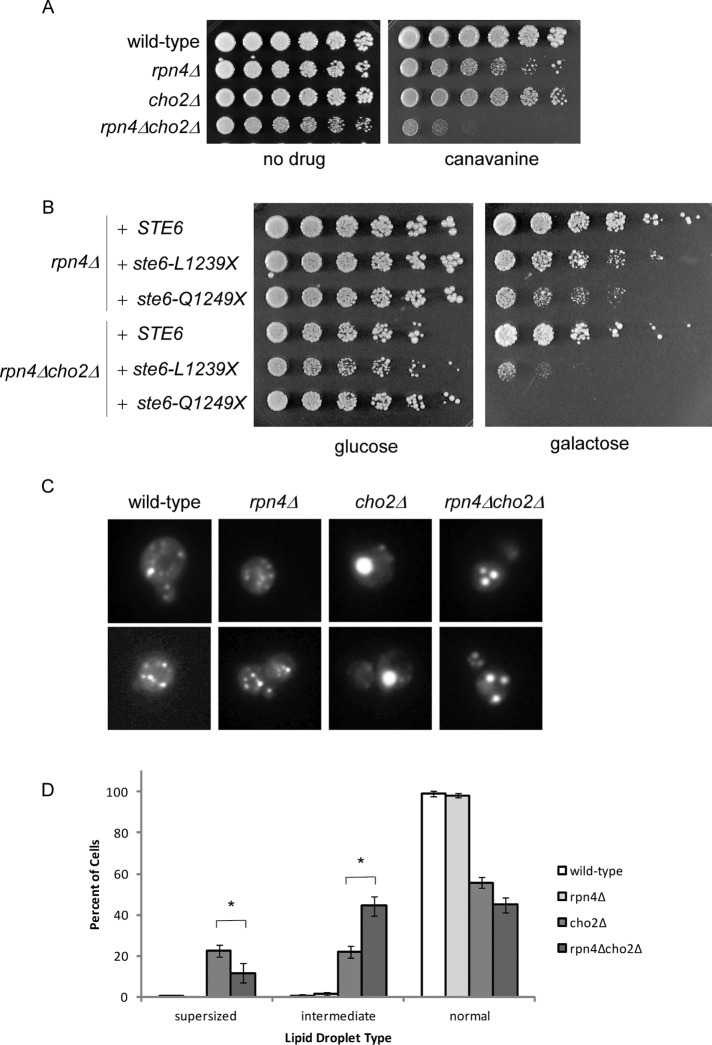

Stress-inducible expression of Lpl1 is dependent on Rpn4 (Figure 1, B and C). Thus the preceding data on Lpl1 suggest a potential relationship between phospholipid metabolism and the Rpn4 proteotoxic stress response, a possibility that has not been previously considered. We therefore examined the consequences of compromising phospholipid metabolism in the rpn4Δ mutant. First, we found that the rpn4Δ cho2Δ mutant showed a strong growth defect when protein misfolding was broadly induced by canavanine (Figure 6A). Next we used the Ste6 assay to determine the effect of a single defined misfolded protein on this mutant. Here we used two distinct Ste6 mutants: L1239X and Q1249X. rpn4Δ alone showed sensitivity to both misfolded proteins, as previously reported (Metzger and Michaelis, 2009). However, when combined with the cho2Δ mutant, growth was markedly diminished (Figure 6B). Finally, we examined whether loss of Rpn4 could recapitulate Lpl1's effects on lipid droplets. Indeed, loss of Rpn4 partially reversed the lipid-droplet phenotype of the cho2Δ mutant, again resulting in an increase in the percentage of cells with an intermediate phenotype (Figure 6, C and D). These findings suggest that two separate proteotoxic stress responses—the Rpn4 response and the UPR—are closely linked to phospholipid metabolism and lipid droplet function.

FIGURE 6:

Rpn4 recapitulates aspects of Lpl1 function. (A) Growth of wild-type, rpn4Δ, cho2Δ, and rpn4Δcho2Δ strains in the presence of canavanine (0.5 µg/ml). Cells were spotted in threefold serial dilutions and cultured at 30°C for 2–4 d. Note that a lower concentration of canavanine was used here than in Figure 4B. (B) Growth of rpn4Δ and rpn4Δcho2Δ strains expressing galactose-inducible wild-type STE6 or the misfolded mutant ste6-L1239X or ste6-Q1249X. Cells were spotted in threefold serial dilutions and cultured for 4 d at 33°C. The cho2Δ mutant alone did not show a phenotype under these conditions (unpublished data). (C) Representative images of lipid droplets, as visualized by fluorescence microscopy, for the indicated strains. cho2Δ cells show a relative accumulation of cells with a single very large (“supersized”) lipid droplet. Similar to cho2Δlpl1Δ, rpn4Δcho2Δ cells show a relative accumulation of cells with an intermediate phenotype (i.e., lipid droplets that are smaller but more numerous than those seen in cho2Δ). (D) Quantitation of normal, intermediate, and supersized lipid droplets. Six hundred cells were counted (in 100 cell groups) for each strain. Error bars represent SDs. Asterisk, statistically significant by Student's t test (p < 0.001). Note that all six strains represented in Figures 5A and 6C were analyzed as a group. Thus the values for wild-type and cho2Δ are the same in both.

DISCUSSION

Novel aspects of the Rpn4 proteotoxic stress response

Rpn4's best-known function is the coordinated regulation of proteasome biosynthesis (Mannhaupt et al., 1999; Xie and Varshavsky, 2001). Accordingly, Rpn4's major known transcriptional targets include the ∼35 subunits of the proteasome, as well as an increasing number of proteasome-associated proteins that may be present in substoichiometric amounts or associate reversibly (Mannhaupt et al., 1999; Leggett et al., 2002; Sa-Moura et al., 2013; Hanna et al., 2014). Thus Lpl1 is a quite unusual transcriptional target for Rpn4. Our assignment of Lpl1 as an Rpn4 effector is supported by two prior microarray studies that detected transcriptional induction of LPL1 in response to different proteotoxic stressors, although no further analysis of Lpl1 was reported (Fleming et al., 2002; Metzger and Michaelis, 2009).

Our results suggest a broader role for Rpn4 in proteotoxic stress responses than was previously anticipated. Indeed, bioinfomatics analyses have identified potential PACE motifs in the promoters of many nonproteasomal genes (Mannhaupt et al., 1999; Shirozu et al., 2015). Moreover, transcriptional profiling experiments indicate many more potential Rpn4 targets, possibly numbering in the hundreds (Jelinsky et al., 2000). The determination of the full breadth and function of the Rpn4 response remains an important goal for future work and will ultimately require a comprehensive analysis of the function of each Rpn4 effector.

Role of phospholipid metabolism in proteotoxic stress responses

The Rpn4 response and the UPR appear to represent largely distinct pathways. Proteasome subunits, for example, are not direct transcriptional targets of the UPR (Travers et al., 2000). Similarly, the dedicated ERAD components controlled by the UPR (e.g., Hrd1, Hrd3, and Ubc7) are not targets of Rpn4. Our work suggests a novel and interesting parallel between the two pathways: each regulates phospholipid metabolism. The UPR stimulates phospholipid synthesis, whereas Rpn4 regulates phospholipid breakdown via Lpl1. The precise role of phospholipid synthesis in the UPR has remained somewhat unclear. An attractive model is that protein misfolding in the ER may be mitigated by expanding the compartment, in effect diluting the concentration of misfolded proteins (Schuck et al., 2009). Because phospholipids are major constituents of membranes, new phospholipid synthesis may be required for this process. An alternate model, not mutually exclusive, is that remodeling of membranes could alter the folding environment within the ER, providing a better environment for protein folding. This could proceed by altering the physicochemical properties of membranes, for example, by changing the hydrophobicity, length, or degree of unsaturation of membrane phospholipids.

An interesting aspect of Lpl1 is that its role in protein degradation became apparent only after compromising the UPR in the hac1Δ mutant. Hac1 regulates many different cellular processes and controls the expression of potentially hundreds of genes (Kaufman, 1999; Travers et al., 2000). In principle, dysregulation of any of these genes could represent the basis for the hac1∆lpl1∆ mutant. Our data suggest that Hac1's control of phospholipid synthesis is particularly relevant for Lpl1 function. This is supported by the observation that impairing phospholipid synthesis in the cho2∆lpl1∆ and the psd1∆lpl1∆ mutants phenocopies the hac1∆lpl1∆ mutant (Figure 4, B and C). A simple model is that recycling of lipid droplet phospholipids by Lpl1 provides precursor products that can be used in new phospholipid synthesis. In this regard, the lipid droplet, in addition to storing neutral lipids, may also serve as a functional reservoir of phospholipids. Alternatively, and not mutually exclusive, the free fatty acids liberated by Lpl1 (Figure 1D) could be used in another process, such as energy production via beta oxidation or lipid modification of proteins (e.g., myristoylation). Further work is needed to test these models.

Role of Lpl1 in lipid droplet function

The lipid droplet is bounded by a phospholipid monolayer. Lpl1 appears to break down these phospholipids (Selvaraju et al., 2014), and this loss might be expected to result in smaller lipid droplet particles. By contrast, we see that the accumulation of very large lipid droplets in the cho2Δ mutant is partially dependent on Lpl1 (Figure 5, A and B). Similarly, simply overexpressing Lpl1 in a wild-type background resulted in larger lipid droplet size (Selvaraju et al., 2014). A key observation in this regard is that the increase in lipid droplet size in the cho2Δ mutant is accompanied by a decrease in the number of lipid droplet particles per cell (Figure 5A; Fei et al., 2011). Thus a straightforward explanation for the seemingly paradoxical effect of Lpl1 is that lipid droplet catabolism by Lpl1 is accompanied by fusion of the smaller lipid droplet particles, resulting in larger but fewer lipid droplets in the cell. Proteomic analysis indicates that Lpl1 is significantly induced in the cho2Δ mutant (see Supplemental Table 3 of Thibault et al., 2012), further supporting this notion. This also suggests that formation of supersized lipid droplets in the cho2Δ mutant may be part of a protective response related to phospholipid deficiency. Indeed, supersized lipid droplets are seen only when cho2Δ cells are cultured in synthetic (i.e., minimal) media (Fei et al., 2011; unpublished data). They are not seen in rich media, presumably because cells can take up precursor products from the extracellular environment and synthesize phospholipids through the alternate Kennedy pathway (Carman and Han, 2011).

Why lipid droplet fusion should occur is unclear. The lipid droplet houses large quantities of neutral lipids, and the phospholipid monolayer ensures that this densely hydrophobic core is shielded from the aqueous environment. Lipid droplet fusion thus may be a response to ensure the integrity of the particle as phospholipids become limiting within the monolayer. Modeled as a sphere, the ratio of volume to surface area should increase as the diameter of the lipid droplet increases. How lipid droplet fusion could occur and whether this is a regulated process also remain unclear. At least one report suggests that purified lipid droplets in vitro could fuse without supplementing ATP or cytoplasmic constituents (Fei et al., 2008).

Relationships between proteotoxic stress, lipid metabolism, and human disease

The role of protein quality control in human disease is well established, particularly in the family of neurodegenerative diseases that are believed to be caused by the toxic accumulation of misfolded proteins. However, a number of intriguing clinical and basic observations over many years has linked proteotoxic stress responses, particularly the unfolded protein response, to diseases of lipid metabolism, including obesity, insulin resistance, and diabetes (Hummasti and Hotamisligil, 2010; Volmer and Ron, 2015). For example, obesity is associated with induction of the unfolded protein response (Ozcan et al., 2004), and weight loss correlates with reduced ER stress (Gregor et al., 2009). Conversely, mutants deficient in the unfolded protein response develop insulin resistance (Ozcan et al., 2004). These relationships between protein degradation, lipid metabolism, and dyslipidemia remain poorly understood at a molecular level. Lpl1 directly links proteotoxic stress responses to lipid droplet function and thus provides a mechanistic basis for further understanding these complex relationships between protein degradation and lipid metabolism.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and plasmids

Yeast strains and plasmids are listed in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. Standard techniques were used for strain constructions and transformations. YPD medium consisted of 1% yeast extract, 2% Bacto-peptone, and 2% dextrose. Synthetic medium consisted of 0.7% Difco Yeast Nitrogen Base supplemented with amino acids, adenine, uracil, and 2% dextrose. Where appropriate, the relevant amino acid or nucleic acid was omitted for plasmid selection. Where appropriate, 2% galactose was used instead of dextrose to induce gene expression.

TABLE 1:

Yeast strains.

| Strain | Genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| BY4741 | MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 | RG Collection |

| rpn4Δ | MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 rpn4::KAN | RG Collection |

| lpl1Δ | MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 lpl1::KAN | RG Collection |

| hac1Δ | MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 hac1::KAN | RG Collection |

| sJH522 | MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 hac1::KAN lpl1::HYG | This study |

| sJH536 | MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 [ycPlac33] | This study |

| sJH537 | MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 lpl1::KAN [ycPlac33] | This study |

| sJH538 | MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 hac1::KAN [ycPlac33] | This study |

| sJH539 | MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 hac1::KAN lpl1::HYG [ycPlac33] | This study |

| sJH540 | MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 hac1::KAN lpl1::HYG [pJH197] | This study |

| sJH559 | MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 [pSM1763] | This study |

| sJH560 | MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 lpl1::KAN [pSM1763] | This study |

| sJH561 | MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 hac1::KAN [pSM1763] | This study |

| sJH562 | MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 hac1::KAN lpl1::HYG [pSM1763] | This study |

| sJH571 | MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 [pJH146] | This study |

| sJH572 | MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 lpl1::KAN [pJH146] | This study |

| sJH573 | MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 hac1::KAN [pJH146] | This study |

| sJH574 | MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 hac1::KAN lpl1::HYG [pJH146] | This study |

| sJH630 | MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 [pSM1897] | This study |

| sJH631 | MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 [pSM2213] | This study |

| sJH632 | MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 lpl1::KAN [pSM1897] | This study |

| sJH633 | MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 lpl1::KAN [pSM2213] | This study |

| sJH634 | MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 hac1::KAN [pSM1897] | This study |

| sJH635 | MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 hac1::KAN [pSM2213] | This study |

| sJH636 | MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 hac1::KAN lpl1::HYG [pSM1897] | This study |

| sJH637 | MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 hac1::KAN lpl1::HYG [pSM2213] | This study |

| cho2Δ | MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 cho2::KAN | RG Collection |

| sJH575 | MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 cho2::KAN lpl1::HYG | This study |

| dga1Δ | MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 dga1::KAN | RG Collection |

| sJH576 | MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 dga1::KAN lpl1::HYG | This study |

| psd1Δ | MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 psd1::KAN | RG Collection |

| sJH598 | MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 psd1::KAN lpl1::HYG | This study |

| sJH612 | MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 cho2::KAN rpn4::NAT | This study |

| sJH614 | MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 rpn4::KAN [pSM1897] | This study |

| sJH615 | MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 rpn4::KAN [pSM2212] | This study |

| sJH616 | MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 rpn4::KAN [pSM2213] | This study |

| sJH638 | MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 cho2::KAN rpn4::NAT [pSM1897] | This study |

| sJH639 | MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 cho2::KAN rpn4::NAT [pSM2212] | This study |

| sJH640 | MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0 cho2::KAN rpn4::NAT [pSM2213] | This study |

Research Genetics (RG) Collection strains are available from ThermoFisher Scientific.

TABLE 2:

Yeast plasmids.

| Plasmid | Details | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| ycPlac33 | Empty vector (CEN/URA3) | Gietz and Sugino (1988) |

| pJH197 | LPL1 (in ycPlac33, CEN/URA3) | This study |

| pSM1763 | CPY*-HA (CEN/URA3) | Huyer et al. (2004) |

| pJH146 | Δ2-GFP-HA (HIS3) | Kruegel et al. (2011) |

| pSM1897 | pGAL1STE6-GFP (2µ/URA3) | Metzger and Michaelis (2009) |

| pSM2213 | pGAL1ste6-Q1249X (2µ/URA3) | Metzger and Michaelis (2009) |

| pSM2212 | pGAL1ste6-L1239X (2µ/URA3) | Metzger and Michaelis (2009) |

Proteomic analysis

Proteomic analysis to determine the cellular response to trivalent arsenic was previously performed using a tandem mass tag-based mass spectrometry approach and was described in detail (Guerra-Moreno et al., 2015). Data for nearly 4600 proteins were obtained in triplicate at 0, 1, and 4 h after treatment. The data shown here for Lpl1 represent further original analysis of that data set.

RT-PCR

RT-PCR was carried out as previously described (Guerra-Moreno and Hanna, 2016). LPL1 was amplified with the primers 5-AATGAGGTCAGAGGAAAATTAGG-3 and 5-TCAATTACTCTTGTGCATCAAG-3. ACT1 was amplified with the primers 5-CTGGTATGTTCTAGCGCTTG-3 and 5-GATACCTTGGTGTCTTGGTC-3. HAC1 was amplified with the primers 5-CACTCGTCGTCTGATACG-3 and 5-CATTCAATTCAAATGAATTCAAACCTG-3. These primers amplify unspliced and spliced HAC1 species. As a positive control for HAC1 splicing, cells were treated with tunicamycin at 5 μg/ml for 1 h.

Phenotypic analysis

Cells from overnight cultures were standardized by optical density and spotted in threefold serial dilutions onto the indicated plates and incubated at the indicated temperatures.

Degradation assays and immunoblot analysis

To analyze total ubiquitin conjugates, whole-cell extracts were prepared from exponential-phase cultures. Cells were normalized by optical density; cell pellets were resuspended in 1× Laemmli loading buffer (LLB) and boiled for 5 min. For all other immunoblots, extracts were prepared by a lithium acetate/sodium hydroxide method as follows. Exponential-phase cultures were normalized by optical density, treated with 2 M lithium acetate on ice for 5 min, and then treated with 0.4 M sodium hydroxide on ice for 5 min. Cell pellets were resuspended in 1× LLB and boiled for 5 min. Analysis was by standard SDS–PAGE followed by immunoblotting. For cycloheximide chase analyses, cycloheximide (100 µg/ml) was added at time 0 to inhibit protein synthesis, and extracts were prepared as described at the indicated time points. Note that the experiments of Figure 3, A–C and E, were carried out at 37°C. Where indicated, the unfolded protein response was induced by treating cells with tunicamycin at 5 μg/ml for 1 h.

The following antibodies were used: anti-ubiquitin (SC-8017; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-Pgk1 (459250; Invitrogen), anti–HA-peroxidase (12013819001; Roche), anti-actin (MA511866; ThermoFisher), anti–phospho-eIF2α (9721S; Cell Signaling Technology), and anti-Kar2 (sc-33630; Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Lipid droplet fluorescence microscopy

Logarithmically growing cells were cultured in minimal medium and shifted to 37°C for 1 h before harvesting. Cells were fixed with 2% formaldehyde and incubated with 0.5 µg/ml BODIPY 493/503 (ThermoFisher Scientific; Selvaraju et al., 2014). Lipid droplets were visualized by fluorescence microscopy using an Olympus BX51 microscope outfitted with a 100× oil immersion objective and the appropriate filters.

To quantify lipid droplets, six groups of 100 cells each were counted sequentially over multiple days for each strain. The normal pattern consisted of 5–10 small dispersed lipid droplets per cell. The “supersized” pattern consisted of a single dominant lipid droplet, typically with no other visible lipid droplets or 1 or 2 small lipid droplets. The intermediate pattern consisted of 2–5 lipid droplets that were intermediate in size between normal and supersized. Lipid droplet distributions were analyzed by SD and two-tailed Student's t test.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Susan Michaelis and Marion Schmidt for plasmids and Daniel Finley and members of the Hanna lab for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant DP5-OD019800.

Abbreviations used:

- CPY

carboxypeptidase Y

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- ERAD

ER-associated degradation

- LLB

Laemmli loading buffer

- PACE

proteasome-associated control element

- RT-PCR

reverse transcription PCR

- UPR

unfolded protein response.

Footnotes

This article was published online ahead of print in MBoC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E16-10-0717) on January 18, 2017.

REFERENCES

- Binns D, Januszewski T, Chen Y, Hill J, Markin VS, Zhao Y, Gilpin C, Chapman KD, Anderson RG, Goodman JM. An intimate collaboration between peroxisomes and lipid bodies. J Cell Biol. 2006;173:719–731. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200511125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carman GM, Han GS. Regulation of phospholipid synthesis in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Annu Rev Biochem. 2011;80:859–883. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060409-092229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox JS, Chapman RE, Walter P. The unfolded protein response coordinates the production of endoplasmic reticulum protein and endoplasmic reticulum membrane. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:1805–1814. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.9.1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fei W, Shui G, Gaeta B, Du X, Kuerschner L, Li P, Brown AJ, Wenk MR, Parton RG, Yang H. Fld1p, a functional homologue of human seipin, regulates the size of lipid droplets in yeast. J Cell Biol. 2008;180:473–482. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200711136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fei W, Shui G, Zhang Y, Krahmer N, Ferguson C, Kapterian TS, Lin RC, Dawes IW, Brown AJ, Li P, et al. A role for phosphatidic acid in the formation of “supersized” lipid droplets. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002201. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming JA, Lightcap ES, Sadis S, Thoroddsen V, Bulawa CE, Blackman RK. Complementary whole-genome technologies reveal the cellular response to proteasome inhibition by PS-341. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:1461–1466. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032516399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gietz RD, Sugino A. New yeast-Escherichia coli shuttle vectors constructed with in vitro mutagenized yeast genes lacking six-base pair restriction sites. Gene. 1988;74:527–534. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90185-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregor MF, Yang L, Fabbrini E, Mohammed BS, Eagon JC, Hotamisligil GS, Klein S. Endoplasmic reticulum stress is reduced in tissues of obese subjects after weight loss. Diabetes. 2009;58:693–700. doi: 10.2337/db08-1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerra-Moreno A, Hanna J. Tmc1 is a dynamically regulated effector of the Rpn4 proteotoxic stress response. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:14788–14795. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.726398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerra-Moreno A, Isasa M, Bhanu MK, Waterman DP, Eapen VV, Gygi SP, Hanna J. Proteomic analysis identifies ribosome reduction as an effective proteotoxic stress response. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:29695–29706. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.684969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna J, Hathaway NA, Tone Y, Crosas B, Elsasser S, Kirkpatrick DS, Leggett DS, Gygi SP, King RW, Finley D. Deubiquitinating enzyme Ubp6 functions noncatalytically to delay proteasomal degradation. Cell. 2006;127:99–111. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna J, Waterman D, Isasa M, Elsasser S, Shi Y, Gygi S, Finley D. Cuz1/Ynl155w, a zinc-dependent ubiquitin-binding protein, protects cells from metalloid-induced proteotoxicity. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:1876–1885. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.534032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hipp MS, Park SH, Hartl FU. Proteostasis impairment in protein-misfolding and -aggregation diseases. Trends Cell Biol. 2014;24:506–514. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2014.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummasti S, Hotamisligil GS. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and inflammation in obesity and diabetes. Circ Res. 2010;107:579–591. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.225698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huyer G, Piluek WF, Fansler Z, Kreft SG, Hochstrasser M, Brodsky JL, Michaelis S. Distinct machinery is required in Saccharomyces cerevisiae for the endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation of a multispanning membrane protein and a soluble luminal protein. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:38369–38378. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402468200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jelinsky SA, Estep P, Church GM, Samson LD. Regulatory networks revealed by transcriptional profiling of damaged Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells: Rpn4 links base excision repair with proteasomes. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:8157–8167. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.21.8157-8167.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman RJ. Stress signaling from the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum: coordination of gene transcriptional and translational controls. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1211–1233. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.10.1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruegel U, Robison B, Dange T, Kahlert G, Delaney JR, Kotireddy S, Tsuchiya M, Tsuchiyama S, Murakami CJ, Schleit J, et al. Elevated proteasome capacity extends replicative lifespan in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002253. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leggett DS, Hanna J, Borodovsky A, Crosas B, Schmidt M, Baker RT, Walz T, Ploegh H, Finley D. Multiple associated proteins regulate proteasome structure and function. Mol Cell. 2002;10:495–507. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00638-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannhaupt G, Schnall R, Karpov V, Vetter I, Feldmann H. Rpn4p acts as a transcription factor by binding to PACE, a nonamer box found upstream of 26S proteasomal and other genes in yeast. FEBS Lett. 1999;450:27–34. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00467-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzger MB, Michaelis S. Analysis of quality control substrates in distinct cellular compartments reveals a unique role for Rpn4p in tolerating misfolded membrane proteins. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:1006–1019. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-02-0140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozcan U, Cao Q, Yilmaz E, Lee AH, Iwakoshi NN, Ozdelen E, Tuncman G, Görgün C, Glimcher LH, Hotamisligil GS. Endoplasmic reticulum stress links obesity, insulin action, and type 2 diabetes. Science. 2004;306:457–461. doi: 10.1126/science.1103160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radhakrishnan SK, Lee CS, Young P, Beskow A, Chan JY, Deshaies RJ. Transcription factor Nrf1 mediates the proteasome recovery pathway after proteasome inhibition in mammalian cells. Mol Cell. 2010;38:17–28. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.02.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radulovic M, Knittelfelder O, Cristobal-Sarramian A, Kolb D, Wolinski H, Kohlwein SD. The emergence of lipid droplets in yeast: current status and experimental approaches. Curr Genet. 2013;59:231–242. doi: 10.1007/s00294-013-0407-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sá-Moura B, Funakoshi M, Tomko RJ, Jr, Dohmen RJ, Wu Z, Peng J, Hochstrasser M. A conserved protein with AN1 zinc finger and ubiquitin-like domains modulates Cdc48 (p97) function in the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:33682–33696. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.521088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuck S, Prinz WA, Thorn KS, Voss C, Walter P. Membrane expansion alleviates endoplasmic reticulum stress independently of the unfolded protein response. J Cell Biol. 2009;187:525–536. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200907074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selvaraju K, Rajakumar S, Nachiappan V. Identification of a phospholipase B encoded by the LPL1 gene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1842:1383–1392. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2014.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seufert W, Jentsch S. Ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes UBC4 and UBC5 mediate selective degradation of short-lived and abnormal proteins. EMBO J. 1990;9:543–550. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08141.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y, Chen X, Elsasser S, Stocks BB, Tian G, Lee BH, Shi Y, Zhang N, de Poot SA, Tuebing F, et al. Rpn1 provides adjacent receptor sites for substrate binding and deubiquitination by the proteasome. Science. 2016;351:6275. doi: 10.1126/science.aad9421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirozu R, Yashiroda H, Murata S. Identification of minimum Rpn4-responsive elements in genes related to proteasome functions. FEBS Lett. 2015;589:933–940. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2015.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffen J, Seeger M, Koch A, Krüger E. Proteasomal degradation is transcriptionally controlled by TCF11 via an ERAD-dependent feedback loop. Mol Cell. 2010;40:147–158. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thibault G, Shui G, Kim W, McAlister GC, Ismail N, Gygi SP, Wenk MR, Ng DT. The membrane stress response buffers lethal effects of lipid disequilibrium by reprogramming the protein homeostasis network. Mol Cell. 2012;48:16–27. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travers KJ, Patil CK, Wodicka L, Lockhart DJ, Weissman JS, Walter P. Functional and genomic analyses reveal an essential coordination between the unfolded protein response and ER-associated degradation. Cell. 2000;101:249–258. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80835-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volmer R, Ron D. Lipid-dependent regulation of the unfolded protein response. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2015;33:67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2014.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter P, Ron D. The unfolded protein response: from stress pathway to homeostatic regulation. Science. 2011;334:1081–1086. doi: 10.1126/science.1209038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CW. Lipid droplet dynamics in budding yeast. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2015;72:2677–2695. doi: 10.1007/s00018-015-1903-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H, Ng BS, Thibault G. Endoplasmic reticulum stress response in yeast and humans. Biosci Rep. 2014;34:e00118. doi: 10.1042/BSR20140058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y, Varshavsky A. RPN4 is a ligand, substrate, and transcriptional regulator of the 26S proteasome: a negative feedback circuit. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:3056–3061. doi: 10.1073/pnas.071022298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.