Abstract

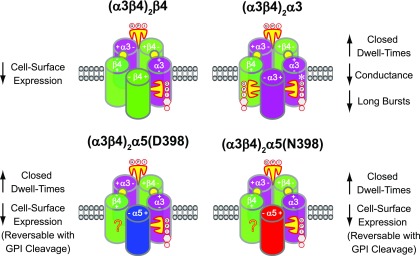

This study investigates—for the first time to our knowledge—the existence and mechanisms of functional interactions between the endogenous mammalian prototoxin, lynx1, and α3- and β4-subunit–containing human nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (α3β4*-nAChRs). Concatenated gene constructs were used to express precisely defined α3β4*-nAChR isoforms (α3β4)2β4-, (α3β4)2α3-, (α3β4)2α5(398D)-, and (α3β4)2α5(398N)-nAChR in Xenopus oocytes. In the presence or absence of lynx1, α3β4*-nAChR agonist responses were recorded by using 2-electrode voltage clamp and single-channel electrophysiology, whereas radioimmunolabeling measured cell-surface expression. Lynx1 reduced (α3β4)2β4-nAChR function principally by lowering cell-surface expression, whereas single-channel effects were primarily responsible for reducing (α3β4)2α3-nAChR function [decreased unitary conductance (≥50%), altered burst proportions (3-fold reduction in the proportion of long bursts), and enhanced closed dwell times (3- to 6-fold increase)]. Alterations in both cell-surface expression and single-channel properties accounted for the reduction in (α3β4)2α5-nAChR function that was mediated by lynx1. No effects were observed when α3β4*-nAChRs were coexpressed with mutated lynx1 (control). Lynx1 is expressed in the habenulopeduncular tract, where α3β4*-α5*-nAChR subtypes are critical contributors to the balance between nicotine aversion and reward. This gives our findings a high likelihood of physiologic significance. The exquisite isoform selectivity of lynx1 interactions provides new insights into the mechanisms and allosteric sites [α(−)-interface containing] by which prototoxins can modulate nAChR function.—George, A. A., Bloy, A., Miwa, J. M., Lindstrom, J. M., Lukas, R. J., Whiteaker, P. Isoform-specific mechanisms of α3β4*-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor modulation by the prototoxin lynx1.

Keywords: GPI-linked proteins, neurotoxins, single-channel electrophysiology, TEVC, concatenated receptor subunits

Cholinergic modulation is known to be involved in a wide array of normal and pathologic brain processes. Thus, the discovery of endogenous modulators of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) that mediate some of the functions of the cholinergic system promises to have significant consequences for health and human behavior (1). Many such modulators, known as prototoxins, are expressed in the CNS and have been shown to serve as allosteric modulators of nAChR function (2–7). The term prototoxin reflects the fact that these modulators have evolutionary origins that are in common with precursors to snake neurotoxin genes: they exhibit a similar 3-fingered receptor binding motif shared with the 3-fingered snake α-neurotoxins, of which α-bungarotoxin and α-cobratoxin are well-known examples (2, 8, 9). Prototoxins form stable complexes with nAChR (10). Lynx1 was among the first prototoxins discovered, and it remains the best-characterized member of the family, with demonstrated effects on cholinergic functions, such as associative learning (11) and motor learning (12). Mice that lack lynx1 have been shown to have an extended critical period of ocular dominance plasticity in the primary visual cortex into adulthood, when this robust plasticity period usually has ended (13). These findings demonstrate significant physiologic roles for lynx1 at expression levels present in vivo. Studies of lynx1, therefore, have implications for cognitive enhancement in dementias and for brain repair (1, 2, 6, 9, 11–16).

nAChR subtypes are assembled as pentameric complexes of homologous subunits (α1–α10, β1–β4, γ, δ, and ε). Pharmacologic and biophysical properties of subtypes that result are determined by their subunit composition, and individual subtypes are associated with a variety of normal physiologic and/or pathophysiologic processes (17–19). Because of the multitude of potential functionally relevant prototoxin/nAChR binding pairs as well as the relatively recent discovery of prototoxin modulation of nAChR function, the subtype selectivity and nature of prototoxin effects is not well defined. For instance, it is known that lynx1 can modulate function of both α4β2- and α7-nAChR subtypes (2), but the full extent of its nAChR interaction set is unknown.

Recent evidence has demonstrated the ability of several members of the prototoxin family to bind with and differentially modulate α4β2-nAChR function (20) but, again, the subtype selectivity of these interactions is not known. However, other prototoxins are known to show decided preferences for their nAChR partners. For example, LYPD6B modulates α3β4* [asterisk denotes the possible or known presence of additional subunits (21)], but not α7-containing nAChR (22). The opposite subtype preference was observed for prostate stem cell antigen, another prototoxin modulator of nAChR function (7). Recent work has demonstrated that prototoxins can also have significant preferences for interaction with particular subunit interfaces within nAChR complexes. For example, lynx1 seems to favor interaction with the extracellular α4/α4 subunit interface of the (α4)3(β2)2 isoform α4β2-nAChR, which alters nAChR assembly, receptor stoichiometry [and therefore the ratio of (α4)3(β2)2 to (α4)2(β2)3 isoform expression], cell-surface expression levels, and, in turn, whole-cell macroscopic currents (15). In a second example, LYPD6B has been shown to functionally interact with α3/α3- and α5-subunit–containing interfaces of α3β4*-nAChR, but not α7- or (α3)2(β4)3-isoform nAChR, which do not contain these interfaces (22).

Within the brain, α3β4*-nAChR are prominently expressed in the medial habenula-to-interpeduncular nucleus pathway (23–27), and they have been repeatedly associated with susceptibility to tobacco use initiation and dependence across multiple human populations (28–32). Animal models are consistent with a role for habenulo-interpeduncular tract α3β4(α5)-nAChR in withdrawal and aversive behavior (33–39), and recent work has indicated that α5*-nAChRs, in particular, regulate reward-inhibiting effects of nicotine (38). Of importance, lynx1 has been shown to be expressed in the medial habenula (6), and lynx1 gene deletion results in habenular neurons showing hypersensitive responses to nicotine (11). Accordingly, we addressed whether α3β4*-nAChR can be functionally modulated by lynx1. Specifically, we wished to determine whether lynx1: 1) alters the number of α3β4*-nAChRs expressed on the cell surface, 2) interacts preferentially with particular α3β4*-nAChR isoforms [expression of which was enforced by using concatenated (linked subunit) constructs (40)], and/or 3) is able to alter the single-channel properties of α3β4*-nAChR.

We demonstrate—for the first time to our knowledge—that lynx1 functionally interacts with α3β4*-nAChR. We further demonstrate that lynx1 reduces the number of functional α3β4*-nAChRs expressed on the plasma membrane and alters single-channel functional properties of only those isoforms that host α3/α3- or α5-subunit–containing interfaces. The precise nature of single-channel alterations also differs between (α3β4)2α3 and (α3β4)2α5 isoforms. These findings demonstrate a previously unappreciated degree of selectivity to prototoxin nAChR interactions and provide new insights into the range of mechanisms and possible receptor sites by which such interactions can alter nAChR function. Data from this and other studies cited earlier support the idea that prototoxin modulators have the ability to shape nicotinic cholinergic responsiveness in a physiologically relevant, spatially, subtype-, and even isoform-selective manner. Because of the involvement of lynx1 in modulating a range of learning and plasticity behaviors, information gained from these types of studies could have important ramifications for a wide array of cholinergic functions, including cognitive enhancement in dementias, such as Alzheimer’s disease, brain repair in cases of stroke, and, especially in the case of prototoxin/α5*-nAChR interactions in the medial habenula-to-interpeduncular nucleus tract, smoking behavior. Approaches used in this study will help to develop a precise understanding of the nature and locations of prototoxin/nAChR binding interactions, providing valuable leads for drug design. The resulting drugs could be aimed at disrupting or encouraging prototoxin/nAChR interactions, and thereby shift the physiologic balances maintained by these interactions. By defining the range of possible mechanisms for allosterically modulating nAChR function, studies such as this can provide specific guidance as to which novel mechanisms can be targeted and then measured to confirm success or failure during drug development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals

All buffer components and pharmacologic reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Fresh stock drug solutions were made daily and diluted as required.

Constructs for human lynx1 and concatenated α3β4- and α3β4α5-nAChR

Human lynx1 cDNA insert was subcloned into a high expression oocyte vector (pSGEM; a kind gift from Dr. M. Hollmann, Ruhr-Universität, Bochum, Germany) that harbored the Kozak consensus sequence and the native lynx1 signal peptide sequence as well as the glycophosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor sequence (Fig. 1A). A mutated version of lynx1, C2C3 (6), was used to control for nonspecific effects of oocytes injected with additional non-nAChR mRNAs. Two cysteines—required for formation of conserved disulfide bridges in the lynx1 topology that are critical for lynx1 function—were mutated to alanines, and the mutated construct was then subcloned into pSGEM (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

cDNA constructs of human lynx1 and concatenated α3β4- and α3β4α5-nAChR. A) Schematic illustration of human lynx1 and mutant C2C3 construct. Green lines within the lynx1 gene represent cysteine residues that confer disulfide bridges in the lynx1 topology. Red lines within the lynx1-C2C3 construct represent the mutated residues (cysteines to alanines). B) Schematic illustration (from top to bottom) of (α3β4)2β4, (α3β4)2α3, (α3β4)2α5(D398), and (α3β4)2α5(N398) constructs. For nAChR concatemers, each construct is flanked with AscI and EcoRV restriction sites (5′ and 3′, respectively; indicated by gray circles) for subcloning into high expression oocyte vectors. Kozac (Koz) and β4 signal peptide (SP) sequences were retained only for position 1 (P1) of the concatemer. Flanking each subunit position are unique restriction sites (indicated by gray triangles) used in concatemer design (AscI and XbaI used in exchanging nAChR subunits at P1; XbaI and AgeI sites were used in exchanging nAChR subunits at P2; AgeI and XhoI sites were used in exchanging nAChR subunits at P3; XhoI and NotI sites were used in exchanging nAChR subunits at P4; and NotI and EcoRV sites were used in exchanging nAChR subunits at P5). Concatemers varied in composition only at P5 and contained either β4 (green box), α3 (fuchsia box), or 2 naturally occurring variants of the α5-nAChR subunit, aspartic acid (D398; blue box), or asparagine (N398; red box). Stop codons were added at the 3′ end of subunit P5. The number of alanine-glycine-serine (AGS) repeats flanking each subunit is listed below each linker region. B′) Assembly and stoichiometry of (α3β4)2β4-, (α3β4)2α3-, (α3β4)2α5(D398)-, and (α3β4)2α5(N398)-nAChR. Concatemers form pentameric receptors by joining the positive interface of the nAChR subunit at P1 and the negative interface of P5. Filled yellow circles represent ACh binding sites. C) Restriction digestion (below each schematic) using unique restriction digest sites was used to verify each subunit within its respective position (P1–P5). An additional restriction digestion (denoted by an asterisk) using ScaI was performed to diagnose correct subunit composition and order.

Fully pentameric nAChR concatemers were constructed as previously described (40, 41). Genes that encoded nAChR subunits were arranged in the order 5′-β4-α3-β4-α3-X-3′, where X indicates the inclusion of an α3-, β4-, or α5-nAChR subunit in the 3′-most position of the cDNA construct (Fig. 1B). As previously demonstrated, the β-α subunit protein pairs of the constructs will assemble to form an orthosteric acetylcholine (ACh) binding site between the complementary (−) face of the β4 subunit and the principal (+) face of the α3 subunit (42). Given this structural feature, constructs that contained β4 or α3 subunits in the fifth position were designated as (α3β4)2β4 and (α3β4)2α3, respectively. Accordingly, constructs that contained the common and risk variants (43, 44) of the α5 subunit were designated as (α3β4)2α5(D398) and (α3β4)2α5(N398), respectively. Subunits were linked by alanine-glycine-serine repeats that were designed to provide a complete linker length, including the C-terminal tail of the preceding subunit, of 40 ± 2 aa. Kozac and signal peptide sequences were removed from all subunit sequences, with the exception of subunits that were expressed in the first position of each concatemer. At the nucleotide level, linker sequences were designed to contain unique restriction sites that allow easy removal and replacement of individual α3, β4, α5(D398), and α5(N398) subunits in the fifth position (Fig. 1B). Sequences of all subunits, together with their associated partial linkers, were confirmed by DNA sequencing (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and assembly of each translated pentamer was verified by restriction digest (Fig. 1C).

Oocyte preparation, RNA synthesis, and RNA injection

Xenopus laevis oocytes (stages V and VI) were purchased from a commercial vendor (Ecocyte Biosciences, Austin, TX, USA) and incubated at 13°C upon arrival. Plasmids that contained lynx1 and concatenated α3β4* constructs were linearized with NheI (2 h at 37°C) and treated with proteinase K (30 min at 50°C). cRNAs were transcribed by using mMessage mMachine T7 kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Reactions were treated with Turbo DNase (Thermo Fisher Scientific ) (1 U for 15 min at 37°C) to remove DNA templates, and cRNAs were purified by using Qiagen RNeasy Clean-up kit (Valencia, CA, USA). cRNA quality was confirmed on a 1% agarose gel and samples were stored at −80°C. For RNA injection, glass micropipettes were broken to achieve an outer diameter of ∼20 μm (resistance of 2–6 mΩ). For 2-electrode voltage-clamp (TEVC) and single-channel recordings, oocytes were injected with either nAChR constructs alone (10 ng) or at a 1:1 lynx1:nAChR RNA ratio (10 ng each). This ratio was selected because it generated a significant reduction in nAChR macroscopic function (i.e., whole-cell currents) across all α3β4*-nAChR constructs while avoiding complete attenuation in nAChR functional expression that would preclude our ability to detect any functional alterations by lynx1 at the macroscopic or single-channel levels. For cell-surface nAChR immunolabeling experiments, oocytes were injected with varying ratios of lynx1:nAChR RNA to determine whether levels of lynx1 that are required to alter cell-surface nAChR expression vary across nAChR constructs. Constructs for lynx1 and (α3β4)2β4-nAChR were coexpressed at 5:1, 1:1, and 1:5 RNA ratios, respectively. Constructs for lynx1 and (α3β4)2α3-nAChR were coexpressed at 25:1, 10:1, 5:1, and 1:1 RNA ratios, respectively. Constructs for lynx1 and (α3β4)2α5(D398)- and (α3β4)2α5(N398)-nAChR were coexpressed at 5:1, 1:1, 5:1, and 1:5 RNA ratios, respectively.

TEVC recordings of α3β4- and α3β4α5-nAChR in Xenopus oocytes

Methods for TEVC electrophysiology were similar to those previously described (40). Seven days after injection, Xenopus oocytes that expressed concatenated α3β4- or α3β4α5-nAChR in the presence or absence of lynx1 coexpression were voltage clamped (microelectrodes filled with 3 M KCl) at −70 mV using an Axoclamp 900A amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Oocytes were placed in a recording chamber that was perfused continuously with oocyte Ringer’s (OR2) solution (in mM: 92.5 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 1 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 5 HEPES, adjusted to pH 7.5 with NaOH) at room temperature (22°C). Recordings were sampled at 10 kHz (low-pass Bessel filter: 40 Hz; high-pass filter: DC), and the resulting traces were saved to disk (Clampex v10.2; Molecular Devices). Data from oocytes with leak currents (Ileak) > 50 nA were excluded from recordings. ACh (10−6 to 10−2.75) was applied by using a 16-channel, gravity-fed perfusion system with automated valve control (AutoMate Scientific, Berkeley, CA, USA). All solutions contained atropine sulfate (1.5 µM) to ensure that muscarinic responses were not recorded. Oocytes were perfused with ACh applications for 5 s, with 60-s washout times between each subsequent application of drug (22, 40).

Immunolabeling of cell-surface α3β4- and α3β4α5-nAChRs

A previous study demonstrated that lynx1 affects assembly of α4 and β2 subunits, which alters the mean subunit stoichiometry, and the number of α4β2-nAChRs that reach the plasma membrane (15). Use of concatemeric nAChR constructs in this study precluded changes in subunit stoichiometry; however, to determine whether lynx1 altered cell-surface nAChR expression, a radiolabeled version of an antibody that recognized the main immunogenic region (MIR) epitopes of both α3- and α5-nAChR subunits, [125I]mAb210 (45, 46), was used to measure cell-surface expression of α3β4*-nAChR. Immunolabeling was performed on the same oocytes that were tested for macroscopic currents to determine the amount of function per nAChR, similar to the approach previously used for α4β2-nAChR (47, 48). Macroscopically, levels of α3β4*-nAChR function elicited by exposure to 1 mM ACh were quantified as Imax (peak current amplitude) values in individual α3β4*-nAChR–expressing oocytes that were measured by using TEVC electrophysiology as previously described. The same oocytes were next incubated individually for 3 h in OR2 buffer that was supplemented with heat-inactivated normal fetal bovine serum (10%, to reduce nonspecific binding; Thermo Fisher Scientific Life Sciences) and a saturating concentration of [125I]mAb210 (5 nM). Unbound [125I]mAb210 was removed via three 2-min washes with ice-cold OR2 buffer. Total [125I]mAb210 binding was determined by liquid scintillation counting at 85% efficiency. Nonspecific binding was determined in each assay by incubating noninjected control oocytes under identical conditions. Specific binding was calculated by subtracting nonspecific binding from total binding to each tested oocyte. Specific cell-surface binding of [125I]mAb210 was converted to nAChR surface expression by using the specific activity of the radiolabeled antibody and accounting for 2 binding sites for (α3β4)2β4-nAChR, 3 binding sites for (α3β4)2α3-nAChR, or 3 binding sites for either (α3β4)2α5(D398)- or (α3β4)2α5(N398)-nAChR.

Phosphotidylinositol PLC treatment

To determine the functional interaction between lynx1 and α3β4- and α3β4α5-nAChR at the level of the plasma membrane, phosphotidylinositol PLC (PI-PLC; Sigma-Aldrich) was used to cleave the GPI anchor of lynx1 and liberate lynx1 from the plasma membrane. Initially, oocytes that expressed α3β4*-nAChR isoforms [in the presence or absence of lynx1; RNA injection ratios for each group: (α3β4)2β4:lynx1 = 1:5; (α3β4)2α3:lynx1 = 1:1; (α3β4)2α5(D398):lynx1 = 1:5; and (α3β4)2α5(N398):lynx1 = 1:5] were incubated for 1 h at 30°C in oocyte incubation buffer that contained 0.25 U/ml of PI-PLC [a concentration that has been shown to effectively cleave lynx1 from its GPI anchor (15)]. After PI-PLC treatment, oocytes were briefly washed twice with 2 ml of fresh oocyte incubation buffer before testing for maximal function and cell-surface expression using TEVC recordings and cell-surface immunolabeling.

Single-channel electrophysiology of α3β4- and α3β4α5-nAChR from Xenopus oocytes

Oocytes were stripped of their vitelline membranes by using fine-tip forceps under a dissecting microscope (×20 magnification) and transferred to a recording chamber that contained OR2 solution. Single-channel α3β4- and α3β4α5-nAChR–mediated currents were recorded from the animal pole of the oocytes under a cell-attached configuration similar to that previously described for nAChR single-channel recordings (49). All single-channel recordings were performed at room temperature (22°C). Patches were clamped at a transmembrane potential of −100 mV. Patch pipettes were fabricated from thick-walled borosilicate glass (2 × 1.12 mm; WPI, Sarasota, FL, USA), and tips were microforged to a final resistance of 15–20 mΩ. To elicit single-channel events, pipettes were filled with OR2 solution that contained ACh that corresponded with the EC50 value for each construct as determined by TEVC. This ACh concentration was used to ensure collection of sufficient open channel events for analysis without producing significant overlap of unitary events or open channel blockade of receptors. Recordings were performed by using an Axopatch 200B amplifier (Molecular Devices). For quality control, patches with seal qualities <10 GΩ were immediately discarded. To test for endogenous mechanosensitive (i.e., stretch activated) channels, negative pressure was applied to each patch and patches were discarded if stretch-activated channels were identified during the recording. Current recordings were filtered at 5 kHz and sampled at 50 kHz by using pClamp 10.4 (Molecular Devices). Under these conditions, no single-channel events were observed in uninjected oocytes or in injected oocytes that were recorded with the patch pipette filled without ACh.

All single-channel recordings were analyzed by using QuB software (v1.4.0.132; http://www.qub.buffalo.edu) (50). QuB software was used for preprocessing and determining open and closed dwell times within bursts, single-channel amplitudes, open probabilities (Popen), and burst duration. Recorded traces were baseline corrected and single-channel events were idealized according to a half-amplitude, threshold-crossing criterion (51). Single-channel amplitudes as well as forward and backward gating rates were derived from the idealized trace by fitting the raw data to simple closed–open (C↔O) kinetic models (52). Stability plots of single-channel amplitudes were generated to determine the quality of each single-channel recording over time and between patches and to calculate the mean amplitude of single events within bursts for each patch. Additional closed states were added to the C↔O model until the log-likelihood score failed to improve by >10 U (50). The opening and closing rate constants were estimated by using maximum interval likelihood, which optimizes rate constants of a user-defined kinetic model according to the interval durations detected by the half-amplitude, threshold-crossing criterion (50, 53). Components with time constants less than the selected dead time (0.2 ms, representing twice the value of the filter rise time) were thereby eliminated from consideration during fitting.

At the single-channel level, α3β4*-nAChR activity in cell-attached mode occurred as bursts/clusters of channel opening events with longer-lived closed intervals interspersed between the clusters, which reflected times when all potentially activatable channels in the patch are desensitized (54, 55). Bursts of single-channel activity were defined as a series of openings separated by closures shorter than the minimum interburst closed duration (or Tcrit) (54, 56) and from other such episodes by prolonged channel desensitization (57). For all groups tested, the minimum interburst closed duration (Tcrit) was calculated by using QuB software (50). Bursts that contained overlapping currents, which indicate 2 simultaneously active channels, were rare and were discarded from analysis. The advantage of using burst analysis has previously been described (58, 59), as it increases the probability that adjacent openings arise from the same receptor. The resulting open time distributions were best fit by a single exponential distribution across all patches studied. Closed time distributions obtained for each patch from α3β4- and α3β4α5-nAChRs were best fitted from an idealized trace by using a triple [for (α3β4)2α3-nAChR recordings] or quadruple (for all other constructs) exponential function for each patch.

Single-channel conductance of α3β4- and α3β4α5-nAChR

Single-channel conductance was estimated by calculating the linear fit of the mean current amplitude, measured across multiple holding potentials (transmembrane potentials of −100, −90, −80, −70, −60, −50, and −40 mV). At each holding potential, for each patch, amplitude histograms were generated for single-channel events and distribution histograms were uniformly best fit with a single gaussian distribution by using the maximum likelihood method.

Data analysis for TEVC recordings

For TEVC recordings, EC50 and Imax values were determined from individual oocytes, then averaged across all recordings. All stimulation protocols began with exposure to a maximally efficacious concentration of ACh (1 mM). This ensured that oocytes expressed functional nAChR before proceeding and provided an internal maximum response control for each oocyte. Relative agonist efficacies were calculated by comparison with this internal ACh control response. EC50 values were determined via nonlinear least squares curve fitting (GraphPad Prism 4.0; GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA) by using unconstrained, monophasic logistic equations to fit all parameters, including Hill slopes. EC50 values are presented as means ± sem. Data were analyzed by using Student’s t test for within-group comparisons or by 1-way ANOVA and Dunnet’s multiple comparison test to compare the mean effects of multiple lynx1 mRNA levels within a group (GraphPad Prism).

Data analysis for single-channel recordings

Single-channel closed dwell times were determined from individual patches, and τ values for each component were averaged across multiple patches. Averaged closed time components for each nAChR construct were compared in the presence or absence of lynx1 (Fig. 5). Single-channel amplitudes and within-burst Popen were determined for each individual patch, and means for single-channel amplitude and Popen were compared in the presence or absence of lynx1. Single-channel slope conductance was determined for individual patches by linear regression of single-channel current-voltage relationships. Mean single-channel conductance was then calculated by averaging single-channel conductance across all patches.

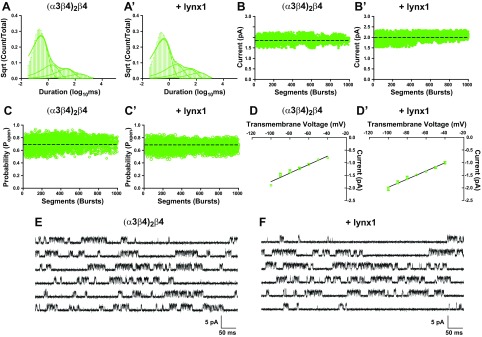

Figure 5.

Effects of lynx1 on single-channel activity of (α3β4)2β4-nAChR. A, A′) Averaged closed time distribution for (α3β4)2β4-nAChR expressed without lynx1 (n = 8 patches; A) or with lynx1 (n = 8 patches; A′). Best-fit closed dwell times for (α3β4)2β4-nAChRs were not significantly different when coexpressed with lynx1 (summarized in Table 2). B, B′) Effects of lynx1 on (α3β4)2β4-nAChR single-channel amplitude. Single-channel amplitudes were determined by pooling all patches and calculating the mean single-channel current amplitude from all bursts (Materials and Methods). Single-channel amplitudes for (α3β4)2β4-nAChR (B) were nearly identical when coexpressed with lynx1 (B′) (P > 0.05). C, C′) Effects of lynx1 on (α3β4)2β4-nAChR Popen. Single-channel Popen for (α3β4)2β4-nAChR (C) did not differ when coexpressed with lynx1 (C′) (P > 0.05). D, D′) Single-channel conductance of (α3β4)2β4-nAChR in the absence (D) or presence (D′) of lynx1. Single-channel slope conductance (γ) was determined by calculating the mean single-channel amplitude across several transmembrane voltages. Slope conductance of (α3β4)2β4-nAChR was not altered when coexpressed with lynx1 (P > 0.05). E, F) Representative single-channel recordings from oocytes that expressed (α3β4)2β4-nAChR (E) and (α3β4)2β4-nAChR + lynx1 (F). Data points represent means ± sem. Differences in single-channel closed dwell times, amplitude, open probability, and conductance were analyzed by using 2-tailed unpaired Student’s t test, and single-channel comparisons are summarized in Tables 2 and 3, together with the number of oocytes tested.

Comparisons in single-channel conductance were made between α3β4*-nAChR constructs in the presence or absence of lynx1. For each group, single-channel burst durations were pooled from multiple patches, and burst duration histograms were generated by using Clampfit software (Molecular Devices). All burst duration histograms were best fit with 2 exponentials. Each individual exponential and their respective time constants (τ) for burst duration were calculated by using Clampfit software. Time constants and proportions of each exponential (i.e., short and long burst durations) were compared between α3β4*-nAChR constructs in the presence or absence of lynx1.

Data are presented as means ± sem, except when error estimates are calculated for gaussian or exponential distributions, in which case single-channel open and closed times are represented as histograms with the best fit value ± sem. For all tests, an α level of <0.05 was considered significant. Single-channel data were analyzed by using Student’s t test when comparing the effects of lynx1 on each nAChR or by 1-way ANOVA and Dunnet’s multiple comparison test when comparing the means across multiple levels of lynx1 mRNA for each nAChR construct (GraphPad Prism).

RESULTS

Lynx1 differentially reduces Imax and cell-surface expression of α3β4*-nAChR isoforms

We began our investigation by determining whether lynx1 was able to alter the magnitude of function and/or cell-surface expression of concatenated (α3β4)2β4-, (α3β4)2α3-, (α3β4)2α5(D398)-, or (α3β4)2α5(N398)-nAChRs. We also wished to determine whether these defined α3β4*-nAChR isoforms exhibited differential sensitivity to such effects. We measured macroscopic currents mediated by α3β4*-nAChR from oocytes that were coinjected with varying ratios of nAChR:lynx1 mRNA, and, subsequently, we measured nAChR cell-surface expression by immunolabeling with [125I]mAb210 on the same oocytes. The resulting data are illustrated in Fig. 2.

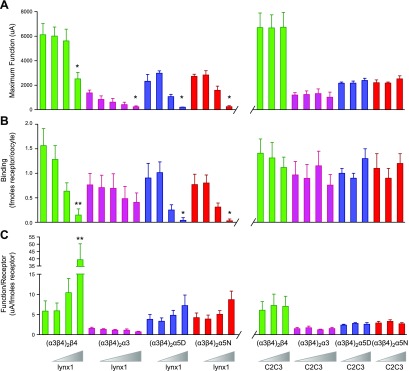

Figure 2.

Effects of lynx1 on cell-surface expression of α3β4- and α3β4α5-containing nAChR. A) (α3β4)2β4-nAChR (green), (α3β4)2α3-nAChR (fuchsia), (α3β4)2α5(D398)-nAChR (blue), or (α3β4)2α5(N398)-nAChR (red) RNAs were coinjected with various concentrations of lynx1 RNA, and maximal current responses were elicited with ACh (1 mM; EC100). Function of the α3β4- and α3β4α5-nAChRs was measured for individual oocytes by using TEVC electrophysiology [(α3β4)2β4, n = 15; (α3β4)2α3, n = 15; (α3β4)2α5(D398), n = 15; and (α3β4)2α5(N398), n = 15]. In addition to ooctyes that expressed α3β4*-nAChR alone (control), different lynx1 mRNA injection ratio ranges were used across isoforms to reflect the differential sensitivity of different α3β4*-nAChR isoforms to modulation by lynx1: (α3β4)2β4:lynx1 = 5:1, 1:1, and 1:5; (α3β4)2α3:lynx1 = 25:1, 10:1, 5:1, and 1:1; (α3β4)2α5(D398):lynx1 = 5:1, 1:1, and 1:5; and (α3β4)2α5(N398):lynx1 = 5:1, 1:1, and 1:5. Coexpression with lynx1 significantly reduced peak currents for (α3β4)2β4-nAChR (at 1:5 nAChR to lynx1 RNA injection ratio; P < 0.05), (α3β4)2α3-nAChR (at 1:1 nAChR to lynx1 RNA injection ratio; P < 0.05), (α3β4)2α5(D398)-nAChR (at 1:5 nAChR to lynx1 RNA injection ratio; P < 0.05), and (α3β4)2α5(N398)-nAChR (at 1:5 nAChR to lynx1 RNA injection ratio; P < 0.05). Substitution of the C2C3-mutated version of lynx1 [RNA injection ratios for (α3β4)2β4:C2C3 = 5:1, 1:1, and 1:5; (α3β4)2α3:C2C3 = 25:1, 10:1, 5:1, and 1:1; (α3β4)2α5(D398):C2C3 = 5:1, 1:1, and 1:5; and (α3β4)2α5(N398):C2C3 = 5:1, 1:1, and 1:5] eliminated all observed effects of lynx1 on peak function, showing dependence on correct lynx1 conformation (right). *P < 0.05. B) Cell-surface immunolabeling performed on the same oocytes tested for maximal function to determine the level of nAChR expression. Cell-surface expression (fmol receptor/oocyte) was significantly reduced for (α3β4)2β4-, (α3β4)2α5(D398)-, and (α3β4)2α5(N398)-nAChR coinjected with lynx1 at an nAChR:lynx1 RNA injection ratio of 1:5 (P < 0.01, P < 0.05, and P < 0.05, respectively). All effects of lynx1 on cell-surface expression were lost for all α3β4*-nAChR isoforms when the C2C3 mutant lynx1 was substituted for wild-type lynx1 (right). C) Normalized function for (α3β4)2β4-, (α3β4)2α3-, (α3β4)2α5(D398)-, and (α3β4)2α5(N398)-nAChR. The amount of function per unit receptor (μA/fmol receptor/oocyte) was calculated for each group coinjected with various concentrations of lynx1 RNA. Concatenated (α3β4)2β4-nAChR showed a significant increase the amount of function per unit receptor when coinjected with lynx1 (1:5 nAChR to lynx1 RNA injection ratio; P < 0.01). Concatenated (α3β4)2α3-, (α3β4)2α5(D398)-, and (α3β4)2α5(N398)-nAChR showed no difference in function per unit receptor when coexpressed with lynx1 (P > 0.05). No differences in function/receptor were observed by using the C2C3 mutant lynx1 (P > 0.05). Data points represent means ± sem. Differences between groups were analyzed by using 1-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparison posttest. Function: (α3β4)2β4, groups = 7, P < 0.05, F = 2.6; (α3β4)2α3, groups = 9, P < 0.05, F = 2.8; (α3β4)2α5(D398), groups = 7, P < 0.05, F = 13.4; and (α3β4)2α5(N398), P < 0.05, F = 14.3. Binding: (α3β4)2β4, groups = 7, P < 0.05, F = 3.7; (α3β4)2α3, groups = 9, P > 0.05, F = 0.8; (α3β4)2α5(D398), groups = 7, P < 0.05, F = 6.8; and (α3β4)2α5(N398), groups = 7, P < 0.05, F = 2.3. Function per receptor: (α3β4)2β4, groups = 7, P < 0.001, F = 6.5; (α3β4)2α3, groups = 9, P > 0.05, F = 1.4; (α3β4)2α5(D398), groups = 7, P > 0.05, F = 2.3; and (α3β4)2α5(N398), groups = 7, P > 0.05, F = 3.7. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Macroscopic currents elicited from each α3β4*-nAChR isoform by exposure to ACh (1 mM, a maximally stimulating concentration for each group) could be significantly attenuated by lynx1 mRNA coinjection (Fig. 2A); however, pronounced differences were seen in the concentration dependence of this lynx1 effect. For example, a nAChR:lynx1 mRNA injection ratio of 1:5 was required to observe a significant loss of (α3β4)2β4-nAChR Imax (reduced by 53.8% ± 4.1% compared with control), whereas Imax measured from oocytes that were injected with (α3β4)2α3 mRNA was much more sensitive [a 1:1 nAChR:lynx1 mRNA injection ratio reduced Imax by 77.3% ± 1.9% compared with oocytes that expressed only (α3β4)2α3-nAChR]. Reduction of (α3β4)2α5(D398)- and (α3β4)2α5(N398)-nAChR macroscopic function at a 1:5 nAChR:lynx1 mRNA injection ratio was similar between constructs hosting the 2 variants (91.2 ± 3.9 and 90.8 ± 2.4%, respectively; P < 0.05). For (α3β4)2α5-nAChR Imax, sensitivity to reduction by lynx1 was intermediate between that of the 2 other isoforms, requiring a 1:5 nAChR:lynx1 coinjection ratio to produce a significant effect [more than that required for (α3β4)2α3-nAChR and the same needed for (α3β4)2β4-nAChR but producing a more profound effect]. It is possible that coinjection with relatively large amounts of lynx1 mRNA could nonspecifically reduce α3β4*-nAChR functional expression. To control for this, we used a mutated, nonfunctional version of lynx1 (C2C3; Materials and Methods) as used in a previous study (6). Coinjection of C2C3-lynx1 mRNA had no effect on ACh-elicited maximal currents from any of the α3β4*-nAChR isoforms tested at the same coinjection ratios that were functionally effective when using native lynx1 (Fig. 2A; P > 0.05). This suggests that the observed effects of lynx1 on receptor functional expression were the result of specific, confirmation-dependent interactions of lynx1 protein with α3β4*-nAChR isoforms.

A lynx1-induced reduction in cell-surface [125I]mAb210 binding was observed for each of the 3 α3β4*-nAChR isoforms that were coinjected with a nAChR:lynx1 RNA ratio of 1:5: (α3β4)2β4, (α3β4)2α5(D398), and (α3β4)2α5(N398). In each case, this reached significance compared with oocytes injected with nAChR mRNA alone (Fig. 2B; P < 0.05, representing a 90 ± 3, 95 ± 4.5, and 96 ± 0.9% reduction in cell-surface binding, respectively). This observation closely mirrored reductions in Imax (shown in Fig. 2A) and suggests that the lynx1-induced reduction in Imax for (α3β4)2β4-, (α3β4)2α5(D398)-, and (α3β4)2α5(N398)-nAChR can primarily be attributed to a reduction in the number of cell-surface receptors. In strong contrast, although a trend suggested a similar reduction in cell-surface expression of (α3β4)2α3-nAChR in the presence of lynx1 (coinjected with a 1:1 ratio of nAChR:lynx1 mRNA) compared with non-lynx1 injected controls, this did not reach significance (Fig 2B; P > 0.05). As this same coinjection ratio was able to significantly reduce (α3β4)2α3-nAChR Imax (Fig 2A), this finding suggests that the observed attenuation in Imax cannot principally be explained by a reduction in cell-surface expression of (α3β4)2α3-nAChR. Instead, an interaction between lynx1 and (α3β4)2α3-nAChR that alters single-channel functional parameters is more likely to be the main cause of the observed loss of macroscopic function. Coexpression with the C2C3-lynx1 mutant had no effect on the amount of cell-surface binding for any of the isoforms studied (Fig. 2B; P > 0.05); therefore, as for effects on Imax, lynx1 must be correctly folded to induce a loss of cell-surface α3β4*-nAChR expression. These observations were not the result of nonspecific effects of coinjecting additional mRNA along with α3β4*-nAChR constructs.

To determine the amount of function per unit of receptor, Imax values were normalized to the amount of nAChR cell-surface expression for each construct in the presence or absence of varying amounts of lynx1 (Fig. 2C). The amount of function per receptor (defined as µA/fmol receptor) increased significantly for (α3β4)2β4-nAChR in the presence of the highest lynx1 coinjection ratio [P < 0.001; (α3β4)2β4:lynx1 RNA injection ratio = 1:5], but not at any other ratio tested. No differences in function per receptor were observed for (α3β4)2α3-, (α3β4)2α5(D398)-, or (α3β4)2α5(N398)-nAChR (P > 0.05). As would be anticipated from the preceding outcomes, the misfolded C2C3-lynx1 mutant was incapable of altering function per receptor.

GPI anchor cleavage differentially alters lynx1 effects on Imax and cell-surface expression across α3β4*-nAChR isoforms

GPI anchor associated with lynx1 can be cleaved by application of PI-PLC. This approach has been used to test for the presence and roles of cell surface–tethered lynx1 (15). Accordingly, we tested the sensitivity to extracellular application of PI-PLC of lynx1 effects on macroscopic Imax and cell-surface expression. Results of these experiments are illustrated in Fig. 3. Of importance, application of PI-PLC alone had no significant effect on Imax, cell-surface nAChR expression, or function/receptor for any α3β4- or α3β4α5-nAChR tested (P > 0.05, accordingly).

Figure 3.

PI-PLC treatment differentially affects lynx1-mediated alterations in α3β4 and α3β4α5 maximum function and cell-surface immunolabeling. A) Maximum current responses were elicited from oocytes (ACh; 1 mM) that expressed (α3β4)2β4-, (α3β4)2α3-, (α3β4)2α5(D398)-, or (α3β4)2α5(N398)-nAChR under the following experimental conditions: nAChR alone (control; n = 9), nAChR + PI-PLC (n = 9), nAChR + lynx1 (n = 9), and nAChR + lynx1 + PLC (n = 9). RNA injection ratios for each group were as follows: (α3β4)2β4:lynx1 = 1:5; (α3β4)2α3:lynx1 = 1:1; (α3β4)2α5(D398):lynx1 = 1:5; and (α3β4)2α5(N398):lynx1 = 1:5. Application of PI-PLC alone had no significant effect on Imax (μA; P > 0.05), cell-surface nAChR expression (fmol receptor/oocyte; P > 0.05), or function per receptor (μA/fmol receptor; P > 0.05). Lynx1 reduced maximal current responses for all α3β4*-nAChR tested: (α3β4)2β4 = P < 0.001; (α3β4)2α3 = P < 0.05; (α3β4)2α5(D398) = P < 0.01; and (α3β4)2α5(N398) = P < 0.01. PI-PLC treatment restored maximum current responses for only (α3β4)2α3-, (α3β4)2α5(D398)-, or (α3β4)2α5(N398)-nAChR (P > 0.05); however, PI-PLC treatment failed to restore maximum current responses for (α3β4)2β4-nAChR coexpressed with lynx1 (P < 0.001) and these were indistinguishable compared with (α3β4)2β4-nAChR + lynx1 + PI-PLC. B) Cell-surface immunolabeling performed on the same oocytes tested for maximal function to determine the level of nAChR expression in the context of PI-PLC treatment. Treatment with PI-PLC restored cell-surface binding (fmol receptor/oocyte) for (α3β4)2α5(D398)- and (α3β4)2α5(N398)-nAChR coinjected with lynx1 (compared with all conditions: P > 0.05). Cell-surface binding of (α3β4)2β4-nAChR + lynx1 treated with PI-PLC was similar to (α3β4)2β4-nAChR + lynx1 without PI-PLC treatment (P > 0.05). PI-PLC failed to restore cell-surface binding for (α3β4)2β4-nAChR coinjected with lynx1, and cell-surface binding remained significantly lower compared with nAChR alone or nAChR + PI-PLC (P < 0.05). No differences in cell-surface binding were observed for oocytes that expressed (α3β4)2α3-nAChR under any experimental conditions (P > 0.05). C) PLC treatment normalizes the lynx1-mediated increase in function/receptor (μA/fmol receptor) of (α3β4)2β4-nAChR in the presence of lynx1 (nAChR + lynx1 compared with nAChR + lynx1 + PLC; P < 0.001). Data points represent means ± sem. Differences within groups were analyzed by using 1-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison posttest (4 groups per comparison). Function: (α3β4)2β4, P < 0.001, F = 72.7; (α3β4)2α3, P < 0.05, F = 5.8; (α3β4)2α5(D398), P < 0.001, F = 23.7; and (α3β4)2α5(N398), P < 0.001, F = 21.2. Binding: (α3β4)2β4, P < 0.001, F = 10; (α3β4)2α3, P > 0.05, F = 2; (α3β4)2α5(D398), P < 0.001, F = 14.2; and (α3β4)2α5(N398), P < 0.001, F = 9.5. Function per receptor: (α3β4)2β4, P < 0.001, F = 39.8; (α3β4)2α3, P > 0.05, F = 1.2; (α3β4)2α5(D398), P > 0.05, F = 3.9; and (α3β4)2α5(N398), P > 0.05, F = 1.8. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

As expected from the preceding set of experiments (Fig. 2), coexpression with lynx1 attenuated Imax for all α3β4- and α3β4α5-nAChR tested (Fig. 3A); however, treatment with PI-PLC affected this outcome differentially. After PI-PLC treatment, Imax values for (α3β4)2α3-, (α3β4)2α5(D398)-, and (α3β4)2α5(N398)-nAChR coexpressed with lynx1 were indistinguishable from Imax values of each respective construct expressed without lynx1 (Fig. 3A; P > 0.05). Compared with the (α3β4)2β4-nAChR control group, PI-PLC treatment failed to normalize the Imax of (α3β4)2β4-nAChRs that were previously coexpressed with lynx1 (>88% ± 6.5% reduction in Imax; P < 0.001). Instead, maximal currents were similar to Imax values of (α3β4)2β4-nAChR that were coexpressed with lynx1 alone (P > 0.05). These results demonstrate that lynx1 is tethered to the cell surface by a GPI anchor and that an intact GPI anchor is an important requirement for the functional effects of lynx1 for α3β4*-nAChR isoforms that harbor an α/α-nAChR subunit interface.

In accordance with the outcomes described in Fig. 2, cell-surface binding of [125I]mAb 210 to (α3β4)2β4-, (α3β4)2α5(D398)-, and (α3β4)2α5(N398)-nAChR, but not (α3β4)2α3-nAChR, was significantly suppressed at lynx1 coinjection ratios that resulted in attenuation of Imax (Fig. 3B; P < 0.05). Similar to Imax, treatment with PI-PLC changed the outcome of expression differently across α3β4*-nAChR isoforms tested. For the (α3β4)2β4-nAChR isoform, PI-PLC treatment failed to recover the lynx1-mediated reduction in cell-surface binding, and (α3β4)2β4-nAChR cell-surface expression remained similar to (α3β4)2β4-nAChR that was coexpressed with lynx1 without PI-PLC treatment (P > 0.05) and significantly lower than that measured on the surface of control oocytes that expressed only (α3β4)2β4-nAChR (Fig. 3B; P < 0.05). In strong contrast to all other isoforms, PI-PLC treatment had no effect on [125I]mAb 210 binding to cell-surface (α3β4)2α3-nAChR, either in the presence or absence of lynx1 coexpression (not significant; P > 0.05). For (α3β4)2α5(D398)- and (α3β4)2α5(N398)-nAChR, the effect of PI-PLC treatment was more dramatic. PI-PLC treatment fully restored [125I]mAb 210 binding to cell-surface (α3β4)2α5-containing nAChR compared with (α3β4)2α5-nAChR that was coexpressed with lynx1 alone (Fig. 3B; P > 0.05). As described in Fig. 2C, coexpression with lynx1 increased the function per unit receptor only for oocytes that expressed the (α3β4)2β4-nAChR isoform; however, this effect was reversed with PI-PLC treatment (Fig. 3C; P < 0.05).

The rapid reversal of lynx1 effects on [125I]mAb 210 binding by PI-PLC treatment—in the case of the 2 (α3β4)2α5 constructs—raises the possibility that lynx1 association with α3β4*-nAChR could interfere with Ab binding. This could occur either directly—by obscuring the MIR epitopes that mAb 210 recognizes—or indirectly—by a more general steric hindrance of nAChR/mAb interactions; however, each concatemeric construct contains multiple subunits that bear the recognized MIR epitope (2 copies of α3 and an additional α3 or α5 subunit in some cases; Fig. 1). This reduces the likelihood of all epitopes being obscured, which would be required to explain the ≥88% observed reductions in binding. Furthermore, the identity and order of all but the fifth subunit in each concatemeric construct is identical, but the effects of lynx1 association and cleavage of its GPI anchor on [125I]mAb 210 binding vary widely across the assembled α3β4*-nAChR isoforms. A more uniform pattern of lynx1 effects would be expected if it simply obstructed binding of the labeled Ab. Accordingly, measurements of [125I]mAb 210 binding must represent valid observations of changes in α3β4*-nAChR surface binding.

It is beyond the scope of the present study to determine the precise mechanisms that underlie the distinctly different kinetics of restoring (α3β4)2α5- vs. (α3β4)2β4-nAChR surface expression after PI-PLC cleavage of the lynx1 GPI anchor; however, complete restoration within 60 min may suggest a role for a rapid (α3β4)2α5-nAChR internalization and recycling mechanism, as has been demonstrated for both neuromuscular and nonmuscle nAChR subtypes (60–63). This observation reinforces the previous indication that lynx1-induced reductions in Imax can primarily be attributed to a reduction in the number of cell-surface receptors. The previous suggestion that lynx1 may alter single-channel functional parameters of (α3β4)2α3-nAChR function is also further supported by the data in Fig. 3. Coexpression with lynx1 reduces macroscopic function of (α3β4)2α3-nAChR without significantly changing cell-surface expression and PI-PLC treatment reverses this effect, also without significantly altering cell surface expression.

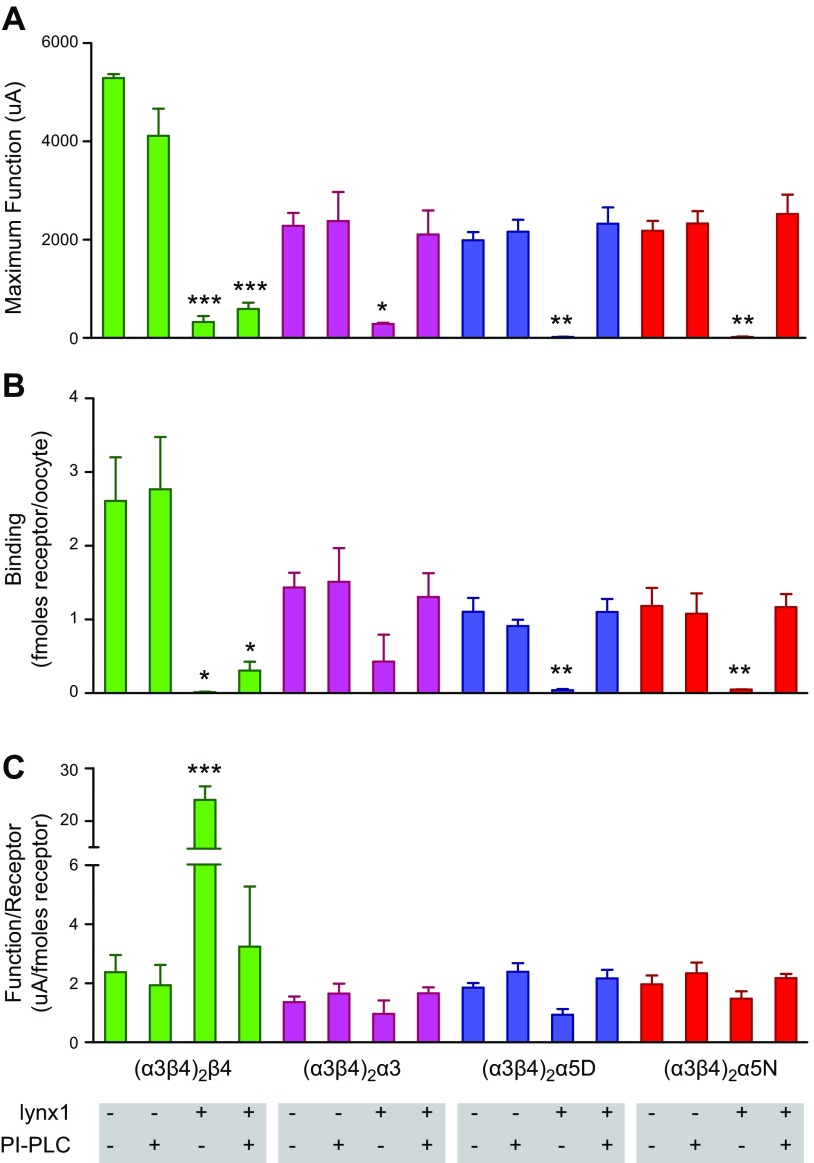

Lynx1 reduces the magnitude of ACh-induced macroscopic α3β4*-nAChR currents without altering EC50 values

We next determined whether lynx1 was able to modulate agonist potency at α3β4*-nAChR. ACh concentration-response profiles of concatenated (α3β4)2β4-, (α3β4)2α3-, (α3β4)2α5(D398)-, or (α3β4)2α5(N398)-nAChR were recorded in the absence or presence of lynx1 [coinjected at a mRNA ratio (w/w) that produced >80% reduction in Imax when present]. The resulting concentration-response curves are illustrated in Fig. 4, and the derived EC50 and Imax values are summarized in Table 1. As shown in Fig. 4A, coexpression with lynx1 did not induce significant differences in ACh EC50 values for any of the constructs studied. This was despite Imax values that were significantly reduced in the presence of lynx1 for each α3β4*-nAChR construct (Fig. 4B). The inability of lynx1 to alter ACh EC50 values while simultaneously reducing macroscopic ACh-induced Imax suggests an allosteric mechanism of action as indicated for other prototoxins. Reduction in macroscopic function could result from reduced α3β4*-nAChR cell-surface expression (as previously addressed) and/or modulation of single-channel properties (e.g., reduced conductance, alteration in burst duration, or reduced Popen within a burst) of α3β4*-nAChR expressed on the plasma membrane.

Figure 4.

Effects of lynx1 on ACh sensitivity and maximal function of α3β4*-containing nAChR. A) ACh concentration-response curves were generated for linked (α3β4)2β4 (i.e., concatemers that contained β4 at position 5; green traces), (α3β4)2α3 (i.e., concatemers that contained α3 at position 5; fuchsia traces), (α3β4)2α5(D398) (i.e., concatemers that contained α5D398 at position 5; blue traces), and (α3β4)2α5(N398) (i.e., concatemers that contained α5N398 risk variant at position 5; red traces). Concatenated nAChR constructs were expressed in the presence (dashed line) or absence (solid line) of lynx1 at a 1:1 RNA injection ratio (Materials and Methods). No significant differences in ACh sensitivity were observed for (α3β4)2β4-, (α3β4)2α3-, (α3β4)2α5(D398)-, or (α3β4)2α5(N398)-nAChR in the presence of lynx1 (P > 0.05). B) Effects of lynx1 on maximal current responses (representing the concentration of ACh that elicited the maximal functional response; EC100) for (α3β4)2β4-, (α3β4)2α3-, (α3β4)2α5(D398)-, and (α3β4)2α5(N398)-nAChR. Peak ACh responses mediated by concatenated (α3β4)2β4-nAChR were significantly lower in the presence of lynx1 (mean current reduction from 6240.5 ± 346.3 to 787.4 ± 468 nA; P < 0.001) and (α3β4)2α3-nAChR (mean current reduction from 1692.2 ± 548.4 to 154.6 ± 19.3 nA; P < 0.05). Similar reductions in maximal function were also observed for concatenated (α3β4)2α5(D398)-nAChR (mean current reduction from 2749.1 ± 285.8 to 280.2 ± 153 μA; P < 0.01) in addition to the (α3β4)2α5(N398) risk variant (mean current reduction from 1618.8 ± 237.5 to 280.2 ± 84.2 μA; P < 0.01). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. C) Representative traces for (α3β4)2β4-, (α3β4)2α3-, (α3β4)2α5(D398)-, and (α3β4)2α5(N398)-nAChR coexpressed with lynx1. Traces represent functional responses for ACh (concentration range: 10−6 to 10−2.75). Data points represent means ± sem. Differences between groups were analyzed by using 2-tailed unpaired Student’s t test for ACh sensitivity and maximal function and are summarized in Table 1, together with number of oocytes tested.

TABLE 1.

ACh CRCs and Imax values

| Parameter | (α3β4)2β4 n = 12 | +lynx1 n = 10 | (α3β4)2α3 n =12 | +lynx1 n =12 | (α3β4)2α5(D398) n = 15 | +lynx1 n = 15 | (α3β4)2α5(N398) n = 15 | +lynx1 n = 13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Best-fit values: TEVC | ||||||||

| Top | 92.1 ± 1.3 | 90.0 ± 2.2 | 117.8 ± 4.0 | 117.1 ± 5.1 | 97.2 ± 1.3 | 6.5 ± 1.3 | 95.4 ± 1.0 | 94.2 ± 1.3 |

| LogEC50 | −4.0 ± 0.02 | −4.1 ± 0.03 | −3.1 ± 0.03 | −3.3 ± 0.05 | −4.1 ± 0.02 | −4.0 ± 0.02 | −4.1 ± 0.01 | −4.0 ± 0.02 |

| Hill slope | 1.9 ± 0.16 | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 1.3 ± 0.07 | 1.0 ± 0.08 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 1.6 ± 0.1 |

| Maximal current response | ||||||||

| Imax (nA) | 6240.5 ± 346.3 | 787.4 ± 468*** | 1692.2 ± 548.4 | 154.6 ± 19.3* | 2749.1 ± 285.8 | 280.2 ± 153** | 1618.8 ± 237.5 | 280.2 ± 84.2** |

CRC, concentration response curve. Data represent means ± sem. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Lynx1 preferentially alters the single-channel properties of α3β4*-nAChR isoforms that contain an α/α interface

To identify any single receptor–level functional changes induced by interactions between lynx1 and α3β4*-nAChR isoforms, we used cell-attached, single-channel recordings. ACh-evoked single-channel currents were elicited with ACh concentrations that corresponded with the respective EC50 value for each α3β4*-nAChR isoform as previously identified by TEVC recordings (Fig. 2A). Single-channel characteristics were compared between each α3β4*-nAChR isoform expressed alone or in the presence of lynx1 coinjected at a 1:1 ratio, which our previous macroscopic observations indicated was sufficient to substantially reduce macroscopic function in each case. Recordings and derived measures of single-channel functional parameters are illustrated in Figs. 5–8 and summarized in Table 2. In all patches tested, single-channel events from (α3β4)2β4-, (α3β4)2α3-, (α3β4)2α5(D398)-, and (α3β4)2α5(N398)-nAChR subtypes displayed bursts of channel openings in addition to single, short-lived openings. This behavior is characteristic of α3β4* single-channel activity (46, 52, 64–68).

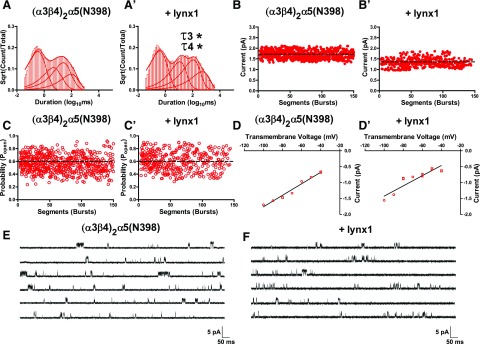

Figure 8.

Effects of lynx1 on single-channel activity of the (α3β4)2α5(N398)-nAChR risk variant. A, A′) Averaged closed time distribution for (α3β4)2α5(N398)-containing nAChR expressed without lynx1 (n = 10; A) or with lynx1 (n = 10; A′). Best-fit closed times for (α3β4)2α5(N398)-nAChR were significantly different for the longest closed time components (τ3 and τ4) when coexpressed with lynx1 (without lynx1: τ3 = 32.2 ± 7.4 ms and τ4 = 135.2 ± 19.7 ms; with lynx1 τ3 = 170.8 ± 74.2 ms and τ4 = 751.1 ± 321.4 ms; P < 0.05). B, B′) Effects of lynx1 on (α3β4)2α5(N398)-nAChR single-channel amplitude. Single-channel amplitudes for (α3β4)2α5(N398)-nAChR (B) were similar when coexpressed with lynx1 (B′) (P > 0.05). C, C′) Effects of lynx1 on (α3β4)2α5(N398)-nAChR Popen. Single-channel Popen for (α3β4)2α5(N398)-nAChR (C) did not significantly differ when coexpressed with lynx1 (C′) (P > 0.05). D, D′) Single-channel conductance of (α3β4)2α5(N398)-nAChR in the absence (D) or presence (D′) of lynx1. No difference in slope conductance of (α3β4)2α5(N398)-nAChR was observed when coexpressed with lynx1 (P > 0.05). E, F) Representative single-channel recordings from oocytes that expressed (α3β4)2α5(N398)-nAChR (E) and (α3β4)2α5(N398)-nAChR coexpressed with lynx1 (F). Differences in single-channel closed dwell times, amplitude, open probability, and conductance were analyzed by using 2-tailed unpaired Student’s t test, and single-channel comparisons are summarized in Tables 2 and 3, together with the number of oocytes tested. *P < 0.05.

TABLE 2.

Measures of single-channel functional parameters

| Parameter | (α3β4)2β4 n = 8 | +lynx1 n = 8 | (α3β4)2α3 n = 10 | +lynx1 n = 10 | (α3β4)2α5(D398) n = 10 | +lynx1 n = 10 | (α3β4)2α5(N398) n = 10 | +lynx1 n = 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Best-fit values: closed dwell times | ||||||||

| C1 dwell (τ ms) | 0.3 ± 0.02 | 0.3 ± 0.02 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 0.3 ± 0.02 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.1 |

| C2 dwell (τ ms) | 2.0 ± 0.20 | 3.4 ± 0.7 | 11.6 ± 2.5 | 45.0 ± 10.0*** | 2.0 ± 0.20 | 11.4 ± 1.6 | 6.2 ± 1.1 | 14.4 ± 5.3 |

| C3 dwell (τ ms) | 30.6 ± 7.4 | 27.9 ± 4.2 | 177.0 ± 51.0 | 1112.5 ± 88.9** | 30.6 ± 7.4 | 111.4 ± 24.4* | 32.2 ± 7.4 | 170.8 ± 74.2* |

| C4 dwell (τ ms) | 298.0 ± 80.3 | 226.5 ± 78.2 | — | — | 298.0 ± 80.3 | 1549.2 ± 205.8*** | 135.2 ± 19.7 | 751.1 ± 121.4* |

| C1 integral | 0.8 ± 0.02 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.7 ± 0.04 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 0.6 ± 0.03 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.4 ± 0.04 |

| C2 integral | 0.1 ± 0.02 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.01 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.02 | 0.2 ± 0.02 | 0.2 ± 0.02 | 0.2 ± 0.06 |

| C3 integral | 0.04 ± 0.003 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 0.2 ± 0.03 | 0.2 ± 0.02 | 0.15 ± 0.02 | 0.06 ± 0.04 | 0.25 ± 0.01 | 0.3 ± 0.02 |

| C4 integral | 0.06 ± 0.003 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | — | — | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.05 ± 0.02 | 0.1 ± 0.02 |

| Best-fit values: single-channel amplitude | ||||||||

| Amplitude (pA) | 1.9 ± 0.03 | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 1.4 ± 0.05 | 0.8 ± 0.05*** | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 1.5 ± 0.03 | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 1.4 ± 0.07 |

| Best-fit values: slope conductance | ||||||||

| γ (ps) | 16.8 ± 0.9 | 16.1 ± 0.9 | 16.7 ± 0.9 | 8.3 ± 0.3*** | 19.5 ± 1.2 | 17.1 ± 1.1 | 18.1 ± 0.6 | 16.0 ± 2.0 |

| Best-fit values: open dwell time within bursts | ||||||||

| τ open (ms) | 0.8 ± 0.03 | 0.7 ± 0.04 | 0.45 ± 0.02 | 0.43 ± 0.05 | 0.5 ± 0.03 | 0.69 ± 0.1 | 0.42 ± 0.04 | 0.48 ± 0.1 |

| Best-fit values: open probability | ||||||||

| Popen | 0.71 ± 0.02 | 0.70 ± 0.03 | 0.34 ± 0.03 | 0.42 ± 0.04 | 0.57 ± 0.03 | 0.59 ± 0.03 | 0.56 ± 0.02 | 0.58 ± 0.03 |

Data represent means ± sem. C, component of exponential fit. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

When coinjected with lynx1, (α3β4)2β4-nAChR single-channel closed times, amplitude, open probability, and conductance were unaltered (Fig. 5). Given the ability of lynx1 to reduce the peak amplitude of (α3β4)2β4-nAChR macroscopic currents (Figs. 2 and 3), these findings suggest that lynx1 exerts its effects on (α3β4)2β4-nAChR macroscopic function entirely by altering the number of (α3β4)2β4-nAChR expressed on the plasma membrane and not by altering (α3β4)2β4-nAChR single-channel function.

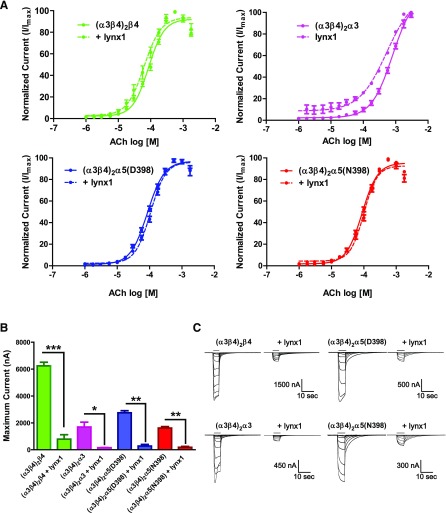

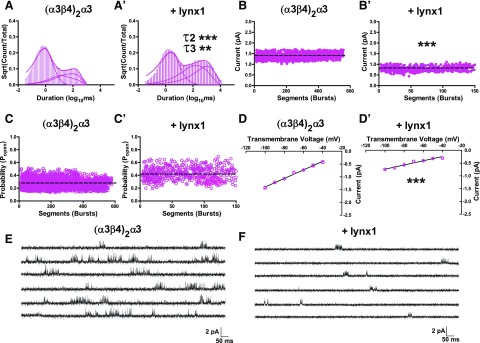

In profound contrast, (α3β4)2α3-nAChR exhibited significant enhancement of single-channel closed dwell times for the longest closed dwell time components (C2 and C3 dwell components) when coexpressed with lynx1 (Fig. 6A, A′ and Table 2; C2 dwell, P < 0.001; and C3 dwell, P < 0.01). In addition to the observed temporal shift in closed dwell times, lynx1 reduced the single-channel amplitude of (α3β4)2α3 by 42.9 ± 6.3% (Fig. 6B, B′; P < 0.001). This change in open amplitude was driven by a corresponding reduction in single-channel conductance by 50.3 ± 3.1% (Fig. 6D, D′; P < 0.001). A modest increase in open probability within bursts was also observed for (α3β4)2α3-nAChR in the presence of lynx1; however, this observation was not statistically significant (Fig. 6C, C′; P > 0.05). Counter to the effects of lynx1 on (α3β4)2β4-nAChR functional expression, these findings suggest that lynx1 interacts functionally with (α3β4)2α3-nAChR primarily at the single-channel level.

Figure 6.

Effects of lynx1 on single-channel activity of (α3β4)2α3-nAChR. A, A′) Averaged representation of closed dwell time distributions for (α3β4)2α3-containing nAChR expressed without lynx1 (n = 10; A) or with lynx1 (n = 10; A′). Best-fit closed dwell times for (α3β4)2α3-nAChR were significantly shifted for the longest closed time components (τ2 and τ3) when coexpressed with lynx1 (τ2 without lynx1 = 11.6 ± 2.5 ms; τ2 with lynx1 = 45.0 ± 10 ms; P < 0.001; and τ3 without lynx1 = 177.0 ± 51.0 ms; τ3 with lynx1 = 1112.5 ± 88.9 ms; P < 0.001). B, B′) Effects of lynx1 on (α3β4)2α3-nAChR single-channel amplitude. As for (α3β4)2β4-nAChR, single-channel amplitudes were determined by pooling all patches and calculating the mean single-channel current amplitude from all bursts (Materials and Methods). Single-channel amplitudes for (α3β4)2α3-nAChR (1.4 ± 0.05 pA; B) were attenuated when coexpressed with lynx1 (0.8 ± 0.05 pA; P < 0.001; B′). C, C′) Effects of lynx1 on (α3β4)2α3-nAChR Popen. Single-channel Popen for (α3β4)2α3-nAChR (0.3 ± 0.02; C) did not significantly differ when coexpressed with lynx1 (0.42 ± 0.03; P > 0.05; C′). D, D′) Single-channel conductance of (α3β4)2α3-nAChR in the absence (D) or presence (D′) of lynx1. Single-channel slope conductance (γ) was determined by calculating the mean single-channel amplitude across several transmembrane voltages. Slope conductance of (α3β4)2α3-nAChR (γ = 16.7 ± 0.9 pS) was reduced when coexpressed with lynx1 (γ = 8.3 ± 0.3 pS; P < 0.001). E, F) Representative single-channel recordings from oocytes that expressed (α3β4)2α3-nAChR (E) and (α3β4)2α3-nAChR coexpressed with lynx1 (F). Data points represent means ± sem. Differences in single-channel closed dwell times, amplitude, open probability, and conductance were analyzed by using 2-tailed unpaired Student’s t test, and single-channel comparisons are summarized in Tables 2 and 3, together with the number of oocytes tested. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

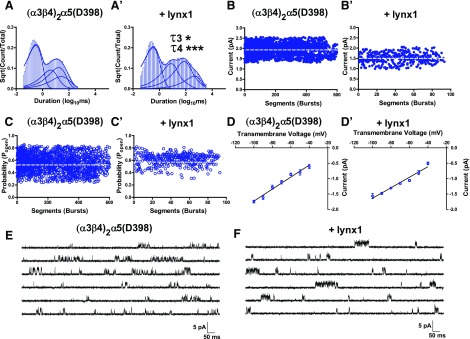

To examine the effects of lynx1 on the single-channel properties of α3β4α5-nAChR, we injected oocytes with RNA that encoded α3β4α5 pentameric constructs expressing the common form of the α5 subunit, (α3β4)2α5(D398), or the risk variant, (α3β4)2α5(N398), in the presence or absence of lynx1. Similar to changes observed for the (α3β4)2α3 subtype, temporal shifts in (α3β4)2α5(D398)-nAChR closed dwell times were observed for the longest closed time components (C3 and C4 dwell components) in the presence of lynx1 (Fig. 7A, A′; increases in C3 dwell, P < 0.001; and C4 dwell, P < 0.001). Unlike for (α3β4)2α3-nAChR, however, no effect was observed on single-channel amplitude, open probability, or conductance of (α3β4)2α5(D398)-nAChR in the presence of lynx1 (Fig. 7B–D′; P > 0.05). Single-channel currents mediated by (α3β4)2α5(N398)-nAChR were nearly identical to those mediated by (α3β4)2α5(D398)-nAChR (Fig. 8). As observed for (α3β4)2α5(D398)-nAChR, (α3β4)2α5(N398)-nAChR showed lynx1-mediated temporal shifts in the long closed time components (Fig. 8A, A′; lengthening of C3 dwell, P < 0.05; and C4 dwell, P < 0.05). Similar to currents mediated by (α3β4)2α5(D398)-nAChR, (α3β4)2α5(N398)-nAChR showed no differences in peak single-channel currents (Fig. 8B, B′; P < 0.05), open probability (Fig. 8C, C′; P < 0.05), or single-channel conductance (Fig. 8D, D′; P < 0.05) in the presence of lynx1.

Figure 7.

Effects of lynx1 on single-channel activity of the (α3β4)2α5(D398)-nAChR variant. A, A′) Averaged representation of closed dwell time distributions for (α3β4)2α5(D398)-containing nAChR expressed without lynx1 (n = 10; A) or with lynx1 (n = 10; A′). Best-fit closed times for (α3β4)2α5(D398)-nAChR were significantly shifted for the longest closed time components (τ3 and τ4) when coexpressed with lynx1 (without lynx1: τ3 = 30.6 ± 7.4 ms and τ4 = 298.0 ± 80.3 ms; with lynx1 τ3 = 111.4 ± 24.4 ms and τ4 = 1549.2 ± 205.8 ms; P < 0.05 and P < 0.001, respectively). B, B′) Effects of lynx1 on (α3β4)2α5(D398)-nAChR single-channel amplitude. Single-channel amplitudes were determined by pooling all patches and calculating the mean single-channel current amplitude from all bursts (Materials and Methods). Single-channel amplitudes for (α3β4)2α5(D398) nAChR (B) were similar when coexpressed with lynx1 (B′) (P > 0.05). C, C′) Effects of lynx1 on (α3β4)2α5(D398)-nAChR Popen. Single-channel open probabilities for (α3β4)2α5(D398)-nAChR (C) did not significantly differ when coexpressed with lynx1 (C′) (P > 0.05). D, D′) Single-channel conductance of (α3β4)2α5(D398)-nAChR in the absence (D) or presence (D′) of lynx1. Single-channel slope conductance (γ) was determined by calculating the mean single-channel amplitude across several transmembrane voltages (Materials and Methods). No difference in slope conductance of (α3β4)2α5(D398)-nAChR was observed when coexpressed with lynx1 (P > 0.05). E, F) Representative single-channel recordings from oocytes that expressed (α3β4)2α5(D398)-nAChR (E) and (α3β4)2α5(D398)-nAChR coexpressed with lynx1 (F). Data points represent means ± sem. Differences in single-channel closed dwell times, amplitude, open probability, and conductance were analyzed by using 2-tailed unpaired Student’s t test, and single-channel comparisons are summarized in Tables 2 and 3, together with the number of oocytes tested. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

Taken together, these data demonstrate the ability of lynx1 to alter α3β4*-nAChR function by preferentially interacting with nAChRs that contain an α/α subunit interface. The effect of lynx1 seems to be greatest for (α3β4)2α3-nAChR, as this selective interaction extends longer closed times for (α3β4)2α3-nAChR and reduces (α3β4)2α3-nAChR conductance, as evident through a reduction in single-channel amplitude. As observed for (α3β4)2α3-nAChR, lynx1 extended (α3β4)2α5(D398) and (α3β4)2α5(N398)-nAChR long closed receptor confirmation durations; however, in contrast, no effect on conductance was observed for either variant in the presence of lynx1. Lastly, these data show that single-channel properties of nAChR that do not contain an α/α subunit interface [e.g., (α3β4)2β4-nAChR] are not affected by the actions of lynx1. Overall, these observations indicate that an α/α interface is required for lynx1 to produce single channel–level functional changes in α3β4*-nAChR populations studied, with the α3/α3 interface producing a wider range of effects than the α3/α5 interface.

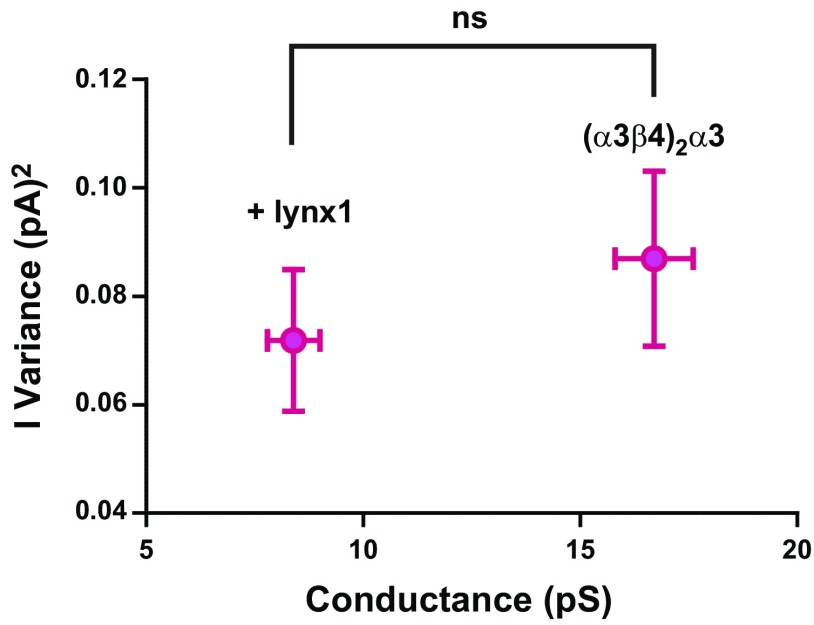

Reduced apparent conductance of (α3β4)2α3-nAChR in the presence of lynx1 does not result from imprecise measurement

Rapidly reversible closing—approaching the time constant of the filter applied during data collection/processing (flicker)—of ion channels can result in a failure to fully resolve the amplitude of single-channel openings, which leads to an imprecise estimate of channel conductance (69–73). Given the apparent ability of lynx1 to selectively reduce the single-channel amplitude of (α3β4)2α3-nAChR, we asked whether this observation reflected our inability to fully resolve unitary events. To answer this question, we compared the variation of single-channel amplitudes of (α3β4)2α3-nAChR in the presence or absence of lynx1. If channel flicker indeed produced a failure to resolve full-scale, single-channel openings in the presence of lynx1, and thus produced an apparent reduction in conductance (γ), then increased variation of measured single-channel amplitudes would be observed (71) as well as a decrease in mean open dwell time. No differences were observed when comparing the variance of single-channel amplitudes of (α3β4)2α3-nAChR in the absence of lynx1 with recordings that were taken from (α3β4)2α3-nAChR coexpressed with lynx1 (Fig. 9; P > 0.05). Furthermore, the open time distribution of events within bursts does not change significantly in the presence of lynx1 (τopen without lynx1 = 0.45 ± 0.02 ms; τopen with lynx1 = 0.43 ± 0.05 ms; Table 2), and both τ values greatly exceed the rise time (0.066 ms) of the 5-kHz filter applied. Together, these observations demonstrate the genuine ability of lynx1 to reduce (α3β4)2α3-nAChR conductance. This observation is not the result of an inability to correctly resolve individual channel openings.

Figure 9.

Reduced conductance of (α3β4)2α3-nAChR in the presence of lynx1 does not result from imprecise measurement. If channel flicker indeed produced a failure to resolve full-scale, single-channel openings and thus produced an apparent reduction in conductance (γ), then increased variation of measured single-channel amplitudes would be observed (71). No differences were observed when comparing the variance of single-channel amplitudes of (α3β4)2α3-nAChRs in the absence of lynx1 with recordings taken from (α3β4)2α3-nAChRs that were coexpressed with lynx1 (P > 0.05). Single-channel variances of (α3β4)2α3-nAChRs were analyzed by using 2-tailed unpaired Student’s t test. Ns, not significant.

Lynx1 reduces the proportion of long bursts of (α3β4)2α3-nAChR

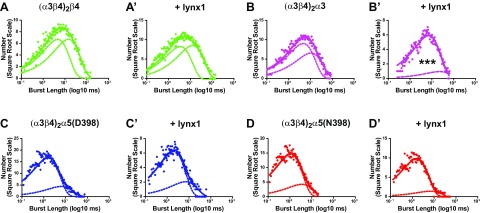

To determine whether burst length was altered in the presence of lynx1, burst time duration histograms were generated with an optimal number of exponential fits (Materials and Methods). Mean burst durations (τ ms) were compared for each group in the presence or absence of lynx1 and are illustrated in Fig. 10 (with the parameters derived from the exponential fits summarized in Table 3). As shown in Fig. 10A–D, coexpression with lynx1 did not induce significant alterations in time constants that characterize short burst relative to long burst durations (B1 dwell and B2 dwell, respectively) for any of the constructs tested, nor were differences seen in closed or open times within bursts (B1 and τopen, respectively; Table 2). However, when coexpressed with lynx1, (α3β4)2α3-nAChR showed a significant increase in the proportion of short bursts vs. long bursts (Fig. 10B′; B1 integral, P < 0.05; and B2 integral, P < 0.05). None of the other constructs tested exhibited a change in the proportion of short vs. long bursts after coexpression with lynx1.

Figure 10.

Lynx1 alters the proportion of short bursts to long bursts for (α3β4)2α3-containing nAChR. A, A′) All-points burst duration distributions for (α3β4)2β4-nAChR in the absence (A) or presence (A′) of lynx1. The numbers of events (square root scale) were plotted as a function of burst length (log10 ms). Solid lines represent the sum of all individual exponentials in each distribution. Dashed lines represent the individual exponential distributions. Time constants for the individual exponential distributions of short and long burst durations as well as the proportion of each (integral of each exponential fit; B1 = short burst duration; B2 = long burst duration) are summarized in Table 2. Burst lengths of (α3β4)2β4-nAChRs and the proportion of short bursts to long bursts were similar in the presence of lynx1 (burst duration > 0.05; burst proportion > 0.05). B, B′) All-points burst duration distributions for (α3β4)2α3-nAChRs in the absence (B) or presence (B′) of lynx1. Burst durations of (α3β4)2α3-containing nAChRs were unaltered in the presence of lynx1 (P > 0.05); however, lynx1 significantly shifted the proportion of short bursts to long bursts (without lynx1: short bursts = 0.57 ± 0.1, long bursts = 0.43 ± 0.1; with lynx1: short bursts = 0.86 ± 0.1, long bursts = 0.14 ± 0.02; short burst, P < 0.001; long burst, P < 0.001). C, C′) All-points burst duration distributions for (α3β4)2α5(D398)-nAChR in the absence (C) or presence (C′) of lynx1. No differences in burst duration (P > 0.05) or the proportion of short bursts to long bursts (short burst, P > 0.05; long burst, P > 0.05) was observed for (α3β4)2α5(D398)-nAChR in the presence of lynx1. D, D′) All-points burst duration distributions for (α3β4)2α5(N398)-nAChR in the absence (D) or presence (D′) of lynx1. Similar to (α3β4)2α5(D398)-containing nAChRs, no differences in burst duration (P > 0.05) or the proportion of short bursts to long bursts (short burst, P > 0.05; long burst, P > 0.05) was observed for (α3β4)2α5(N398)-nAChRs in the presence of lynx1. Data points represent means ± sem. Within-group differences in single-channel burst length and burst proportion were analyzed by using 2-tailed unpaired Student’s t test, and single-channel comparisons are summarized in Table 3, together with the number of oocytes tested. ***P < 0.001.

TABLE 3.

Mean burst duration and proportion

| Parameter | (α3β4)2β4 n = 8 | +lynx1 n = 8 | (α3β4)2α3 n = 10 | +lynx1 n = 10 | (α3β4)2α5(D398) n = 10 | +lynx1 n = 10 | (α3β4)2α5(N398) n = 10 | +lynx1 n = 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 dwell (τ ms) | 4.7 ± 0.1 | 4.2 ± 0.2 | 6.5 ± 0.1 | 7.1 ± 0.2 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 1.6 ± 0.1 |

| B2 dwell (τ ms) | 14.6 ± 0.1 | 14.3 ± 0.1 | 11.8 ± 0.2 | 12.9 ± 1.0 | 6.0 ± 1.1 | 7.1 ± 1.0 | 3.3 ± 2.0 | 3.6 ± 2.0 |

| B1 integral | 0.49 ± 0.02 | 0.48 ± 0.02 | 0.57 ± 0.03 | 0.86 ± 0.1*** | 0.78 ± 0.1 | 0.73 ± 0.1 | 0.75 ± 0.1 | 0.79 ± 0.2 |

| B2 integral | 0.51 ± 0.02 | 0.52 ± 0.02 | 0.43 ± 0.1 | 0.14 ± 0.02*** | 0.22 ± 0.1 | 0.27 ± 0.1 | 0.25 ± 0.1 | 0.21 ± 0.1 |

Data are for best-fit values: burst length and burst proportion. Data represent means ± sem. *P < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

The findings in this study demonstrate for the first time, to our knowledge, a functional interaction between lynx1 and α3β4*-nAChR. Recent investigations into the functional modulation of α4β2-containing nAChR by endogenous prototoxin neuromodulators have converged on 2 distinct mechanisms. By forming stable complexes with nAChR subunits, prototoxins (represented by lynx1 and lynx2) have been shown to alter nAChR trafficking and insertion into the plasma membrane (15, 20), and prototoxins have also been shown to extend their role by interacting directly with nAChR at the level of the plasma membrane. This is exemplified by the ability of ly6g6e to potentiate α4β2-nAChR macroscopic function via slowed desensitization of α4β2-nAChR currents (20). In this study, we show for the first time that α3β4*-nAChRs are subject to both mechanisms of regulation by lynx1, with the balance between mechanisms dictated by the particular α3β4*-nAChR isoform being targeted.

To uncover these novel insights into the mechanisms and nAChR sites by which prototoxins can modulate nAChR function, we used completely defined concatemeric constructs. This was essential to avoid confounds associated with expression of diverse α3β4*-nAChR populations via differential subunit assembly (46, 68). Of importance, pentameric α3β4*-nAChR constructs used in this study have already been shown to faithfully reproduce the macroscopic functional properties and pharmacology of self-assembled α3β4*-nAChR (40). Our results from this study extend the previous macroscopic characterization to show that the single-channel properties of α3β4*-nAChR concatemers also resemble those of the same subtype when heterologously expressed from single subunits (46, 52, 64–68).

Our demonstration that lynx1 attenuates macroscopic currents across multiple α3β4*-nAChR isoforms is consistent with our previous findings that demonstrated a similar effect of lypd6b (22); however, we are able to provide much greater mechanistic insight in the present study of lynx1. For example, we demonstrate that the lynx1-induced reduction in Imax of (α3β4)2β4-, (α3β4)2α5(D398)-, and (α3β4)2α5(N398)-nAChR was accompanied by a reduction in the number of nAChRs at the plasma membrane. In most cases, this resulted in the function per cell-surface nAChR remaining consistent (Fig. 2C). There was, however, one exception: at the highest lynx1 mRNA coinjection only, function per cell-surface (α3β4)2β4nAChR increased significantly. Of interest, function per receptor levels in the absence of lynx1 are <5 µA/fmol across all α3β4*-nAChR isoforms, which is much lower than that previously measured for α4β2*-nAChR using a similar approach (48, 74). Given the greater bursting behavior and slower macroscopic desensitization of α3β4*- (references cited above, data from this study) vs. α4β2*-nAChR function (6), it would be anticipated that the opposite would be true. This would seem to indicate that the majority of cell-surface α3β4*-nAChRs are in a quiescent state. If so, this suggests an explanation for the ability of lynx1 to increase function per cell-surface (α3β4)2β4-isoform-nAChR. The same mechanism that lowers cell surface expression of this isoform, which expresses more strongly than the other isoforms, in the presence of lynx1 may also provide a degree of quality control, increasing the proportion of functional nAChRs within the smaller overall cell-surface population. This explanation also fits with a previous observation that β4-nAChR subunits lack endoplasmic reticulum–retention/retrieval motifs that were found within β2-nAChR subunits, and have an endoplasmic reticulum–export motif missing from β2 subunits (75), which results in increased surface expression—potentially at the expense of quality control. This explanation is further reinforced by the fact that surface expression of α3β4*-nAChR—especially of the isoform that contains 3 β4 subunits—is much higher than that of α4β2*-nAChR as measured in our previous studies (48, 74), and, as demonstrated in the current study, removal of these putative quiescent (α3β4)2β4-nAChRs from the cell surface can be reversed by GPI anchor cleavage, which suggests a possible cell-surface role for lynx1 in this quality control phenomenon.

Of interest, lynx1 failed to reduce the total number (α3β4)2α3-nAChRs on the plasma membrane at an expression level that significantly reduced macroscopic function. This suggested an important role for lynx1 in altering single-channel functional parameters of this isoform. Indeed, we demonstrate here that coexpression with lynx1 alters (α3β4)2α3-nAChR single-channel closed dwell times by increasing the length of longer duration, interburst, single-channel closed times. These have previously been described to correspond with desensitized states (76, 77). A similar phenomenon was observed in (α3β4)2α5(D398)- and (α3β4)2α5(N398)-nAChR. This suggests a preference of lynx1 to bind to and therefore stabilize desensitized states of (α3β4)2α3- and (α3β4)2α5-nAChR. Overall, this would reduce function by moving nAChR population equilibria toward more inactive (i.e., closed) conformations; however, it is essential to note that the cell-attached patch-clamp approach we used is not capable of determining the number of activatable receptors per patch. Accordingly, it is possible that the increased closed times may instead—or in addition—reflect a function of lynx1 to induce channel inactivation [i.e., entry into nonfunctional states as a result of post-translational modifications (78)]. In addition, the rapidly reversible removal of (α3β4)2α5(D398)- and (α3β4)2α5(N398)-nAChR from the cell surface may reduce the mean number of functional channels per patch, which also would tend to increase the length of interburst closed dwell times. This explanation is less likely in light of our findings for the other 2 isoforms studied. For example, (α3β4)2α3-nAChR interburst times changed significantly in the presence of lynx1 without any changes in cell surface expression, and the opposite was true for the (α3β4)2β4-nAChR isoform. Finally, it is important to distinguish the single-channel desensitization/inactivation mechanism, as considered here, from a previous study that demonstrated the ability of lynx1 to alter the macroscopic rate of α4β2-nAChR desensitization (6). The increased macroscopic desensitization rate described in the study by Ibanez-Tallon et al. can be attributed to a lynx1-induced shift in α4β2 receptor stoichiometry to favor the low-sensitivity α4β2-nAChR isoform (15). This stoichiometric shift may also explain the previously observed changes in single-channel amplitudes.