Abstract

Latina women in stable relationships have risks for human immunodeficiency virus and other sexually transmitted infections. Improving safe sexual communication (SSC) could enable women to accurately assess and mitigate their risk of infection within their relationship. Literature to identify psychosocial correlates that facilitate or inhibit SSC between Latina women and their partners has not yet been synthesized. The purpose of this study was to conduct an integrative review and synthesis of empirical and theoretical research that examines psychosocial correlates of SSC among adult Latina women from the United States, Latina America, and the Caribbean with stable male partners. A systematic search of LILACS, EBSCO, and PsychInfo databases was conducted to identify qualitative and quantitative studies that investigated psychosocial correlates of SSC among adult Latina women with a stable male partner. Pertinent data were abstracted and quality of individual studies was appraised. A qualitative synthesis was conducted following Miles and Huberman's method. Five qualitative and three quantitative studies meet eligibility criteria. Factors related to SSC related to three main themes: (1) relationship factors such as length, quality, and power/control, (2) individual factors including attitudes, beliefs, background, behaviors, and intrapersonal characteristics, and (3) partner factors related to partner beliefs and behaviors. The interplay of relationship, individual, and partner factors should be considered in the assessment of SSC for Latina women with their stable partners. To inform future interventions and clinical guidelines, additional research is needed to identify which factors are most related to SSC for this population, and how comparable experiences are for Latina women of different subcultures and living in different countries.

Keywords: Sexual communication, Latinos, HIV prevention, sexual behavior, women

Introduction

Latina women in the United States, Latin America, and the Caribbean experience a disproportionate burden of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and other sexually transmitted infections. In the United States, Latina women are approximately 1.5 times more likely to be infected than heterosexual Latino men (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015). In the Dominican Republic, the proportion of HIV cases that are women increased from 27% in 2003 (Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS [UNAIDS]), 2004) to 51% in 2013 (UNAIDS, 2013). In many Latin American countries, such as Mexico and Columbia, the HIV epidemic has also been found to be affecting a greater number of women than previously (UNAIDS, 2006).

Latina women in stable heterosexual relationships have risk factors for HIV infection (UNAIDS, 2006), but have received little attention in HIV prevention research compared to other populations such as female sex workers. In Latino communities, it is common for men, including those in stable relationships, to have multiple concurrent sex partners (Centro de Estudios Sociales y Demográficos [CESDEM] & ICF International, 2014; Marín, Tschann, Gómez, & Gregorich, 1998). Furthermore, a large disparity in condom use has been found between stable versus casual partners. For example, in the Dominican Republic, as low as 0.4–4% of married or cohabitating partners report using condoms (CESDEM & ICF International, 2014) compared to 68% of non-married and 40% of non-cohabitating men and women (Halperin, de Moya, Perez-Then, Pappas, & Garcia Calleja, 2009). This may be in part due to the meanings assigned to condom use among Latino partners related to trust and intimacy (Kerrigan et al., 2003, 2006; Perez-Jimenez, Seal, & Serrano-Garcia, 2009), along with religious beliefs of Catholic Latinos that prohibit contraceptive use.

Safe sexual communication (SSC) may be a more feasible and effective method of preventing HIV/sexually transmitted infections than consistent condom use among Latina women in heterosexual stable relationships. SSC includes verbal or non-verbal relaying of information to one's partner regarding methods of preventing HIV/sexually transmitted infections such as condom negotiation, sexual history, notification of new HIV/sexually transmitted infections diagnosis or other concurrent sexual partners, or discussing testing for HIV/sexually transmitted infections. Greater levels of SSC have been found to be associated with increased HIV testing among husbands (Manopaiboon et al., 2007), as well as reduced HIV transmission (Saul et al., 2000) and increased condom use (El-Bassel et al., 2003; Noar, Carlyle, & Cole, 2006) among stable partners.

To reduce risk of HIV among Latina women in heterosexual relationships by improving SSC, an adequate understanding is needed of the barriers and facilitators of SSC and what types of SSC are most commonly utilized and avoided in the context of a stable relationship. Researchers have examined which factors are related to SSC Latinas in stable heterosexual relationships, however there has not yet been a review or synthesis of these studies. Therefore, the purpose of this integrative review is to review, appraise, and synthesize empirical and theoretical research that examines psychosocial correlates of SSC among adult Latina women in stable heterosexual relationships from the United States, Latin America, and the Caribbean.

Methods

This study followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman, & Group, 2009), where possible, to increase the rigor of procedures and reporting.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Qualitative and quantitative primary studies of any design except interventional studies were eligible if they met the following criteria: (1) sample consisted of adult (18 or older) Latina women in a stable heterosexual relationship or included a mix of ethnicities or sexes with data on adult Latina women that could be abstracted, (2) qualitative studies with the purpose of examining Latina women's experiences of talking with their partner about different methods of preventing HIV/sexually transmitted infections OR quantitative studies with an outcome of partner SSC, (3) set in the United States, Latin America, or the Caribbean, (4) reported in English or Spanish, and (5) published as a peer reviewed journal article with full text available in the databases searched.

Studies with the following characteristics were excluded: (1) sample consisted of transgender individual or women who were involved with illicit drug use, mentally ill, or disabled, (2) examined only behavioral correlates, communication only about pregnancy prevention or contraception, sexual pleasure, or sexual act, (3) set in Spain or Brazil, or (4) published as a book chapter, review article, opinion, or dissertation. No limits were placed on date of publication.

Database and search strategy

A two-stage search strategy was used (Counsell, 1997; Dickersin, Scherer, & Lefebvre, 1994). First, a preliminary limited search of Ovid MEDLINE was conducted to identify optimal search terms. Second, a comprehensive systematic search was conducted using three databases: Literatura Latino Americana e do Caribe em Ciências da Saúde (LILACS, Latin American and Caribbean Health Science Literature), PsychInfo, and EBSCO. Within EBSCO, the following databases were searched: Chicano Database, Gender Studies Database, SocIndex, Social Work Abstracts, Family and Society Studies Worldwide, and Social Sciences Full Text.

Study selection

An online program designed to facilitate the screening process for review articles (Covidence, www.covidence.org) was used by both authors to review all articles yielded by the comprehensive search. First, all titles and abstracts were independently screened for inclusion criteria by each author. Next, both authors independently conducted a full text evaluation of potentially eligible articles independently. Throughout, both authors discussed all discrepancies and reached consensus about articles that met inclusion criteria.

Data abstraction

Two separate data collection forms for qualitative and quantitative studies were developed prior to data abstraction based on the purpose of the integrative review to facilitate systematic examination and organization of information from included studies (Higgins & Green, 2005). The forms were then pilot tested and modified to improve the adequacy of abstracted data.

The first author abstracted the following data on an Excel spread sheet for all studies: (1) sample characteristics, (2) sampling method, (3) inclusion and exclusion criteria, (4) setting, (5) recruitment and enrolment, (6) purpose, (7) study design, (8) phenomenon of focus, (9) guiding theory or framework, (10) data collection method, (11) data analysis method, (12) major findings and reporting method, and (13) correlates of SSC. For quantitative studies, data were also abstracted pertaining to: (1) sample size calculation, (2) response rate, (3) method of measuring SSC outcome, and (4) independent variables examined. The second author verified data abstracted for each study by reviewing data in the spread sheet.

Quality assessment

Qualitative studies were appraised using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme tool (Chenail, 2011), which examined ten aspects of the study. Response options for the specific questions were modified to include: “Yes” (2 points), “Partially” (1 point), “Can't tell” (0 points), or “No” (0 points). The assessment was scored as a percentage determined by adding the points obtained (numerator) and dividing by the total possible points (20 points). For the purpose of this integrative review, focus groups were not considered a qualitative study design, but rather a method of data collection.

Quantitative studies were appraised using a modified version of the “Quality assessment tool for observational cohort and cross-sectional studies” (National Institute of Health, 2014). Questions not applicable for cross-sectional studies were removed, as all included studies were cross-sectional. Ultimately, eight assessment criteria were used. The response options and scoring methods were modified to match those used for qualitative studies. However the total possible score was 16.

Data synthesis/analysis

Miles and Huberman's method of qualitative data analysis guided the analysis and synthesis of data (1994), as suggested by past scholars (Whittemore & Knafl, 2005). This method involves five main steps: (1) data reduction, (2) data display, (3) data comparison, (4) conclusion drawing, and (5) verification.

During the data reduction phase, we extracted significant correlations with SSC from quantitative studies and influential factors of SSC expressed by participants mentioned in qualitative studies. All findings, including conflicting findings, were included in the synthesis. During the data display phase, we combined, organized, and displayed coded data.

During the data comparison phase, we examined the summary of findings for patterns, themes, and relationships. Notes of conflicting findings were kept. During the conclusion-drawing phase, we determined a final list of categories and overall general themes and identified commonalities and differences across studies. During the verification phase, we crosschecked overall thematic categories with results from the individual included studies to ensure that the results and interpretation of the body of evidence were grounded in data from the original primary articles.

Results

Study selection

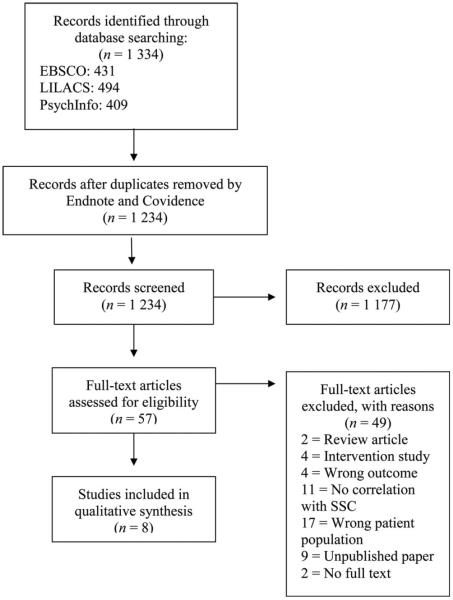

Figure 1 provides detail regarding the literature search and selection process. Of the 1234 titles and abstracts screened for eligibility, 1177 of these articles were excluded. Of the 57 full text articles screened, primary reasons for exclusion were: wrong participant population (n = 17), no correlations with SSC explored (n = 11), and unpublished paper (n = 9). Ultimately, five quantitative (Alvarez & Villarruel, 2015; Ashburn, Kerrigan, & Sweat, 2008; Castañeda, 2000; Moore, Harrison, Kay, Deren, & Doll, 1995; Saul et al., 2000) and three qualitative studies (Alvarez & Villarruel, 2013; Davila, 2002; McQuiston & Gordon, 2000) were included in the review and synthesis.

Figure 1.

Selection process for inclusion in the integrative review.

Description of studies

Table 1 describes characteristics of the included studies. A range of purposes related to investigating SSC were reported across studies. Qualitative studies designs included qualitative descriptive (Alvarez & Villarruel, 2013), naturalistic inquiry (Davila, 2002), and unspecified qualitative design (McQuiston & Gordon, 2000). All quantitative studies utilized a cross-sectional design (Alvarez & Villarruel, 2015; Ashburn et al., 2008; Castañeda, 2000; Moore et al., 1995; Saul et al., 2000). Half of the studies included women only (Ashburn et al., 2008; Davila, 2002; Moore et al., 1995; Saul et al., 2000). The majority of studies reported mean participant age as low to mid-30s (Ashburn et al., 2008; Castañeda, 2000; Davila, 2002; Moore et al., 1995). The most common reported participant ethnicity was Mexicans or Mexican American (Castañeda, 2000; Davila, 2002; McQuiston & Gordon, 2000; Moore et al., 1995). All but one study (Alvarez & Villarruel, 2013, 2015; Castañeda, 2000; Davila, 2002; McQuiston & Gordon, 2000; Moore et al., 1995; Saul et al., 2000) were conducted in the continental United States.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies.

| Authors (year) | Study design and purpose | Sample | Variables/phenomena | Analysis method and results | Quality score (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alvarez and Villarruel (2013) | • Qualitative descriptive | • 20 Latino men and women; n = 10 women; mean age of women 24.2 years | Phenomenon: Sexual communication | • Grounded Theory (Corbin & Strauss, 2008) | 70 |

| • To describe sexual communication among young adult Latinos | • Education: 4 high school graduate or less and 5 some college | • 5 themes: (1) Barriers to verbal communication, (2) facilitators of communication, (3) Sex and Condom use, (4) Contexts for verbal communication, (5) Non-verbal sexual communication | |||

| • Ethnicity: Not Reported (NR) | |||||

| • Location: Midwest (USA) | |||||

| Alvarez (2015) | • Cross-sectional | • 220 Latino men and women; n = 111 women; mean age of women 24.28 years | • Dependent SSC variable: Sexual health communication | • Multiple regression | 87.5 |

| • To examine the role of traditional gender norms, relationship factors, intrapersonal factors, and acculturation as statistical predictors of three different types of sexual communication in Latino women and men | • Education: NR | • Independent variables: Traditional gender norms, sexual relationship power, length of time in relationship, difference in time in US, age difference of partners, relationships status, attitudes toward sexual communication, sexual attitudes, social norms about preventative behaviors, perceived partner approval about sexual communication, subjective norms, acculturation | • Positive association: Relationship length (β = .21, p < .05), Relationship power (β = .27, p < .001), Attitudes toward sexual health communication (β = .32, p < .001), Subjective norms toward sexual communication (β = .28, p < .001), Acculturation (β = 5.67, p < .001) | ||

| • Ethnicity: NR | • Negative association: Difference in time in US (β = −.18, p < .05), Attitudes toward pleasure discussions (β = −.29, p < .05), partner approval toward sexual communication (β = −.29, p < .05) | ||||

| • Location: Midwest (USA) | |||||

| Ashburn et al. (2008) | • Cross-sectional | • 273 Latina women; mean age 36.49 years | • Dependent SSC variable: HIV-related negotiation | • Multivariate logistic regression | 75 |

| • To examine the relationship between women's empowerment and negotiation of partner's behavior change to avoid HIV infection among partnered sexually active women in rural DR | • Education: 69% some primary school | • Independent variables: Micro-credit loan participation, level of participation in women's groups, control of own money, perception of partner's monogamy, age, education, residence, religion, number of children living at home | • Positive association: Unfaithful partner (AOR = 6.39, p < .001), Control own money (AOR = 2.43, p < .001), residence in Peravia (AOR = 3.53, p < .001) | ||

| • Ethnicity: Dominican | • Negative association: Evangelical religion (AOR = 0.12, p < .001), no religious affiliation (AOR = 0.29, p < .05) | ||||

| • Location: Southwestern DR | |||||

| Castañeda (2000) | • Cross-sectional | • 115 Latino men and women; n = 76 women; mean age 30.8 years | • Dependent SSC variable: HIV-related communication | • Hierarchical multiple regression | 68.8 |

| • To determine the association of relationship variables to participants' HIV risk perception, use of condoms, and HIV-related communication with a relationship partner | • Education: 26% less than high school, 94.73% high school graduate | • Other dependent variables: Condom use, HIV risk perception | • Positive association: Intimacy (β = .35, p < .02) | ||

| • Ethnicity: 98.68% Mexican American, 1.3% other Latina | • Independent variables: Demographics, relationship status, commitment, intimacy, overall sexual satisfaction in relationship, sexual regulation, level of acculturation | ||||

| • Location: Southwestern US | |||||

| Davila (2002) | • Naturalistic inquiry | • 20 Latin a women; mean age 30.7 years | Phenomenon: Condom negotiation | • Content analysis | 75 |

| • Explore the influence of abuse on the condom negotiation attitudes, behaviors, and practices of Mexican American women involved in abusive relationships | • Education: 5–12 years (mean = 10.4 years) | • Three main categories: (1) “He beat me”, (2) “He made me feel bad”, (3) “He forced me” | |||

| • Ethnicity: Mexican American | |||||

| • Location: South-central Texas | |||||

| McQuiston and Gordon (2000) | • Qualitative | • 31 Latino men and women, n = 16 women; age 20–29 years | Phenomenon: Condom negotiation | • Content analysis | 60 |

| • Gain insight into (a) whether newly immigrated Mexican men and women in the Southeast discussed HIV/STD prevention with each other, and (b) how condom use was discussed | • Education: mean = 8.73 years | • Four themes: (1) Women: Communication comes first – it is safe sex, (2) Men: Trust comes first – it is safe sex, (3) Women: Machismo and Trust, (4) Men, Machismo, and Trust | |||

| • Ethnicity: Mexican American | |||||

| • Location: Southeastern US | |||||

| Moore et al. (1995) | • Cross-sectional | • 189 Latina women; mean age 30 years | • Dependent SSC variable: Level of HIV-related communication | • Ordinary least squares regression | 75 |

| • To determine the factors influencing Hispanic women's HIV-related communication and condom use with their primary male partner | • Education: 68% at least high school | • Other dependent variables: Condom use | • Positive association: perceived risk of HIV infection (β = .30, p = .0001), openness of communication with partner (β = .17, p = .05) | ||

| • Ethnicity: n = 44 Dominican, n = 54 Puerto Rican, n = 91 Mexican | • Independent variables: acculturation, perceived risk for HIV, conflict, sex communication, openness of communication, expected partner reactions to request for condom use, age, Hispanic subgroup, whether woman had multiple sex partners | • Negative association: Mexican ethnicity (β = −.36, p = .0003), woman has other sex partners (β = −.28, p = .0003) | |||

| • Location: New York City, NY and El Paso Texas | |||||

| Saul et al. (2000) | • Cross-sectional | • 187 Latina women; age NR | • Dependent SSC variable: HIV-related communication | • Structural equation modeling | 75 |

| • To empirically test the association between power and women's HIV-related communication and condom use with male partners | • Education: NR | • Independent variables: Sexual power (education, employment, decision-making, perceived alternatives to relationship, commitment to the relationship, investment in the relationship, absence of abuse in relationship), age, relationship length | • Negative association: Currently employed (t (1166) = −3.32, p < .05), high commitment to the relationship (t (1166) = −3.67, p < .01) | ||

| • Ethnicity: Puerto Rican | |||||

| • Location: New York City, NY |

Note: NR, not reported.

HIV-related communication or negotiation (Ashburn et al., 2008; Castañeda, 2000; Moore et al., 1995; Saul et al., 2000) was the most common form of SSC investigated. Among quantitative studies, the most common independent variables examined were acculturation (Alvarez & Villarruel, 2015; Castañeda, 2000; Moore et al., 1995) and age (Ashburn et al., 2008; Moore et al., 1995; Saul et al., 2000). Correlations were primarily examined using regression methods (Alvarez & Villarruel, 2015; Ashburn et al., 2008; Castañeda, 2000; Moore et al., 1995). Unspecified methods of content analysis were primarily reported as the analysis method for qualitative data (Davila, 2002; McQuiston & Gordon, 2000). Results of the individual studies are reported in Table 1.

Study quality

Quality scores for qualitative studies ranged between 60% (McQuiston & Gordon, 2000) and 75% (Davila, 2002). Major threats to quality were inadequate reporting of the relationship between the researcher and the participants, data analysis methods (Alvarez & Villarruel, 2013; Davila, 2002; McQuiston & Gordon, 2000), and ethical considerations (Davila, 2002; McQuiston & Gordon, 2000). Ratings for quantitative studies ranged between 68.8% (Castañeda, 2000) and 87.5% (Alvarez & Villarruel, 2015). Common threats to quality were inadequate description and reporting of psychometrics, particularly the validity, of the exposure and outcome measures (Alvarez & Villarruel, 2015; Ashburn et al., 2008; Castañeda, 2000; Moore et al., 1995; Saul et al., 2000), as well as lack of justification of sample size (Ashburn et al., 2008; Castañeda, 2000; Moore et al., 1995; Saul et al., 2000),

Findings of data synthesis

Table 2 provides a detailed the thematic map with corresponding categories of variables related to SSC across all included studies. Ultimately, three main themes emerged that summarize factors related to SSC between Latina women and their stable male partners: (1) relationship factors, (2) individual factors, and (3) partner factors.

Table 2.

Thematic map of factors that facilitate or hinder SSC for Latina women in stable relationships.

| Relationship factors | Individual factors | Partner factors |

|---|---|---|

| Relationship length | Attitudes/beliefs | Attitudes/beliefs |

| + Longer relationship (Alvarez & Villarruel, 2013, 2015; McQuiston & Gordon, 2000) | + Greater perceived risk of HIV infection (Davila, 2002; McQuiston & Gordon, 2000; Moore et al., 1995) | − Partner has greater endorsement of traditional gender roles (“Machismo”) (Alvarez & Villarruel, 2013; McQuiston & Gordon, 2000) |

| + More positive attitudes or subjective norms toward SSC (Alvarez & Villarruel, 2015) | ||

| Relationship quality | + Greater perceived openness of partner to SSC (Alvarez & Villarruel, 2013) | Behaviors |

| + Good general communication (McQuiston & Gordon, 2000; Moore et al., 1995) | − Poor attitude toward pleasure discussions (Alvarez & Villarruel, 2015) | + Partner has other concurrent sex partners (Ashburn et al., 2008) |

| + Greater intimacy (Castañeda, 2000) | + Positive partner response to SSC (McQuiston & Gordon, 2000) | |

| + Mutual trust (McQuiston & Gordon, 2000) | − Feeling embarrassed (Alvarez & Villarruel, 2013) | |

| + Mutual understanding (McQuiston & Gordon, 2000) | − Not wanting to know (Alvarez & Villarruel, 2013) | − Partner refuses to talk about SSC (McQuiston & Gordon, 2000) |

| − Greater endorsement of traditional gender roles (McQuiston & Gordon, 2000) | − Partner substance use (Davila, 2002) | |

| Use of initial sex activity | − High levels of trust of her partner (McQuiston & Gordon, 2000) | |

| + Use of initial sexual activity to create foundation for SSC (Alvarez & Villarruel, 2013) | − Low perceived partner approval toward sexual communication (Alvarez & Villarruel, 2015) | |

| Background characteristics | ||

| Difference in time in the US | + Residence in Peravia (compared to Azua), DR (Ashburn et al., 2008) | |

| − Greater difference in time living in the US between partners (Alvarez & Villarruel, 2015) | + Greater acculturation (Alvarez & Villarruel, 2015) | |

| − Mexican ethnicity compared to Puerto Rican (Moore et al., 1995) | ||

| Power/control | − Children (Davila, 2002) | |

| + Greater relationship power (Alvarez & Villarruel, 2015) | − Evangelical religion or no religious affiliation (Ashburn et al., 2008) | |

| + Greater control of own money (Ashburn et al., 2008) | Behaviors | |

| − Currently employed (Saul et al., 2000) | + Use of communication technology (Alvarez & Villarruel, 2013) | |

| − High commitment to maintaining the relationship (et al., 2000) | − Woman has other concurrent sex partners (Moore et al., 1995) | |

| − Feeling powerless (Davila, 2002) | ||

| − Fear of or actual physical, psychological, and sexual abuse from partner (Davila, 2002) | Intrapersonal characteristics | |

| − Poor sense of identity (Davila, 2002) | ||

| − Low self-esteem (Davila, 2002) | ||

| Skills | ||

| − Difficulty problem solving (Davila, 2002) |

Notes: + indicates factors that facilitate SSC; − indicates factors that hinder SSC; DR, Dominican Republic.

Subthemes that comprised relationship factors include: relationship length, relationship quality, use of initial sexual activity to create a foundation for communication, difference in time in the use between partners, and power and control in the relationship. Subthemes within individual factors included: attitudes/beliefs, background characteristics, behaviors, intrapersonal characteristics, and skills. Subthemes that emerged under partner factors were partner's attitudes and behaviors.

Discussion

Five quantitative and three qualitative research studies that examined psychosocial correlates of SSC between adult Latina women and their stable male partners in the United States, Latina America, and the Caribbean were reviewed, appraised, and synthesized in this integrative review. Various factors were found to be related to SSC included relationship factors, individual factors, and partner factors and confirmed that while certain factors facilitate SSC between Latina women and their stable male partners, they still face many challenges.

Relationship factors have been found to be related to SSC among various populations. As in this review (Alvarez & Villarruel, 2015; Davila, 2002), past research with a sample of Latina women of mixed relationships status also found relationship power in general to be related to SSC (Davila, 1999). Similarly, among Kenyan women who are cohabitating with their male partners, participation in decision-making has been found to be positively associated with spousal communication about HIV prevention (Chiao, Mishra, & Ksobiech, 2011). Like the Latina women in studies included in this review (Davila, 2002), past research with African-American women who have stable partners has also found interpersonal violence to be related to various forms of SSC (Morales-Alemán et al., 2014). Despite evidence that relationship power is related to SSC, it remains unclear which specific aspects of sexual relationship power are most related to SSC. Future research should consider taking a more comprehensive and detailed approach to investigating constructs within sexual relationship power as they relate to SSC.

Using the initial sexual activity to create foundation for SSC was another relationship factor found to facilitate SSC for Latinas in stable relationships (Alvarez & Villarruel, 2013), as well as among women in primary relationships of various different ethnicities (Pulerwitz & Dworkin, 2006). Gaining a better understanding of timing of SSC between stable partners may provide valuable for improving the effectiveness of this HIV prevention behavior.

Individual factors such as, specific Latino subculture (Moore et al., 1995), and acculturation level (Alvarez & Villarruel, 2015), appear to not only be related to SSC but also to condom use among stable partners, as well (Deren, Shedlin, & Beardsley, 1996; Moreno & El-Bassel, 2007). Further research on SSC is needed with Latinas of different subcultures and who are living in countries outside of the United States to facilitate comparison across Latino subcultures and country of current residence. Specifically, how comparable SSC among Latinas living in the United States is to Latinas living in Latin American or Caribbean countries, and whether level of acculturation to American culture has an influence on SSC for Latinas. Additionally, structural factors such as access and exposure to HIV/sexually transmitted infection prevention services may also differ across countries. The possible influence of these factors on SSC among Latinas needs to be examined to determine generalizability of findings.

Like in this review, where cultural norms and gender roles were found to have an effect on SSC for Latina women in stable relationships where neither partner has HIV (Alvarez & Villarruel, 2015; McQuiston & Gordon, 2000), past research has found this to be true among Latinos in serodiscoradant relationships, as well (Orengo-Aguayo & Pérez-Jiménez, 2009). This may also be a factor that affects couples regardless of ethnicity, as previous research has also found a significant affect on SSC among an ethnically diverse sample of men and women in the United States in stable relationships (Pulerwitz & Dworkin, 2006). HIV prevention efforts for Latinas should tailor interventions to the cultural context and address culturally bound messages related to HIV prevention behaviors.

Perceived negative partner reaction to SSC also seems to be an important factor for many women in stable relationships, not only among Latinas. Among Puerto Rican women in serodiscordant relationships, fear of being judged, misunderstood or partner not taking the topic seriously inhibited SSC (Orengo-Aguayo & Pérez-Jiménez, 2009). Similarly, among a sample of predominantly white and African-American college students (Dilorio, Dudley, Lehr, & Soet, 2000), as well as a sample of African-American adolescents (Sionéan et al., 2002) perception of more positive partner attitude toward SSC was associated with greater SSC and more consistent refusal of unwanted sex.

Finally, fidelity of both the female and male partner also appears to influence SSC not just among Latina women's relationships. Among an ethnically diverse sample of young couples in the United States, it was found that if the woman has sexual partners outside of their relationship this negatively affects SSC (Albritton et al., 2014). With regards to male partners, as opposed to facilitating SSC as it was recorded among Latino couples in this review (Ashburn et al., 2008), among cohabitating couples in Kenya, if the male had other sexual partners, the couple was less likely to have discussed HIV prevention (Chiao et al., 2011).

Limitations

There are limitations to this review. We did not search for or examine unpublished or gray literature. It is possible that eligible studies were missed, despite our best efforts to develop a comprehensive search strategy. Additionally, due to the small number of studies and characteristics of the sample, it is not appropriate to generalize findings to Latina women living outside of the United States or to women of all Latino subcultures. Furthermore, results of the data synthesis are descriptive, so conclusions could not be made about pooled statistical correlations using a meta-analysis. Similarly, because all studies were qualitative or cross-sectional in design, causation cannot be assumed.

Conclusion

Multiple relationship, individual, and partner factors were reported to be related to the SSC that Latina women have with their stable male partners. More qualitative research is needed on forms of SSC other than condom negotiation. Future quantitative studies on the topic should consider a more comprehensive approach to variable selection and include more variables specifically related to the close relationship context. In addition, more research is needed with Latinas of different subcultures and with those who live outside of the United States. With this information, a more accurate and complete understanding of the needs of Latina women in stable heterosexual relationships with regards to SSC can be achieved, and recommendations for clinical practice and interventional research can be made.

Acknowledgments

Funding This work was supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research, National Institutes of Health under [grant number T32NR013454]: Training in Interdisciplinary Research to Prevent Infections (TIRI).

Footnotes

Disclosure statement No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Albritton T, Fletcher D, Divney A, Gordon D, Magriples U, Kershaw TS. Who's asking the important questions? Sexual topics discussed among young pregnant couples. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2014;37(6):1047–1056. doi: 10.1007/s10865-013-9539-0. doi:10.1007/s10865-013-9539-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez CP, Villarruel AM. Sexual communication among young adult heterosexual Latinos: A qualitative descriptive study. Hispanic Health Care International. 2013;11(3):101–110. doi: 10.1891/1540-4153.11.3.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez CP, Villarruel AM. Association of gender norms, relationship and intrapersonal variables, and acculturation with sexual communication among young adult Latinos. Research in Nursing & Health. 2015;38(2):121–132. doi: 10.1002/nur.21645. doi:10.1002/nur.21645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashburn K, Kerrigan D, Sweat M. Micro-credit, women's groups, control of own money: HIV-related negotiation among partnered Dominican women. AIDS And Behavior. 2008;12(3):396–403. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9263-2. doi:10.1007/s10461-007-9263-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castañeda D. The close relationship context and HIV/AIDS risk reduction among Mexican Americans. Sex Roles. 2000;42(7/8):551–580. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention HIV and AIDS among Latinos CDC fact sheet. 2015 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/docs/factsheets/cdc-hiv-latinos-508.pdf.

- Centro de Estudios Sociales y Demográficos & ICF International . Encuesta Demográfica y de Salud 2013. Author; Santo Domingo: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Chenail RJ. Learning to appraise the quality of qualitative research articles: A contextualized learning object for constructing knowledge. The Qualitative Report. 2011;16(1):236–248. [Google Scholar]

- Chiao C, Mishra V, Ksobiech K. Spousal communication about HIV prevention in Kenya. Journal of Health Communication. 2011;16(11):1088–1105. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2011.571335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of qualitative research: Techniques to developing grounded theory. 3rd ed. Sage; Los Angeles, CA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Counsell C. Formulating questions and locating primary studies for inclusion in systematic reviews. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1997;127(5):380–387. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-5-199709010-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davila YR. Mexican-American women: Barriers to condom negotiation for HIV/AIDS prevention (Ph.D.) University of Texas Health Science Center; San Antonio: 1999. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cin20&AN=2004138562&site=ehost-live Available from EBSCOhost cin20 database. [Google Scholar]

- Davila YR. Influence of abuse on condom negotiation among Mexican-American women involved in abusive relationships. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2002;13(6):46–56. doi: 10.1177/1055329002238025. doi:10.1177/1055329002238025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deren S, Shedlin M, Beardsley M. HIV-related concerns and behaviors among Hispanic women. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1996;8(4):335–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickersin K, Scherer R, Lefebvre C. Systematic reviews: Identifying relevant studies for systematic reviews. British Medical Journal. 1994;309(6964):1286–1291. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6964.1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilorio C, Dudley WN, Lehr S, Soet JE. Correlates of safer sex communication among college students. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2000;32(3):658–665. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Bassel N, Witte SS, Gilbert L, Wu E, Change M, Hill J. The efficacy of a relationship-based HIV/STD prevention program for heterosexual couples. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:963–969. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.6.963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halperin DT, de Moya EA, Perez-Then E, Pappas G, Garcia Calleja JM. Understanding the HIV epidemic in the Dominican Republic: A prevention success story in the Caribbean? Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndroms. 2009;51:S53–S59. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181a267e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions Version 4.2.5: The Cochrane collaboration. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.; Chichester, West Sussex: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS Dominican Republic: Epidemiological fact sheets on HIV/AIDS and sexually transmitted infection. 2004 Retrieved from http://data.unaids.org/publications/fact-sheets01/dominicanrepublic_en.pdf.

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS Latin America. Fact Sheet. 2006 Retrieved from http://data.unaids.org/pub/EpiReport/2006/20061121_EPI_FS_LA_en.pdf.

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS Dominican Republic HIV and AIDS estimates: 2013. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/dominicanrepublic.

- Kerrigan D, Ellen JM, Moreno L, Rosario S, Katz J, Celentano DD, Sweat M. Environmental-structural factors significantly associated with consistent condom use among female sex workers in the Dominican Republic. AIDS. 2003;17:415–423. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200302140-00016. doi:10.1097/01.aids.0000050787.28043.2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerrigan D, Moreno L, Rosario S, Gomez B, Jerez H, Barrington C, Sweat M. Environmental-structural interventions to reduce HIV/STI risk among female sex workers in the Dominican Republic. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:120–125. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.042200. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2004.042200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manopaiboon C, Kilmarx PH, Supawitkul S, Chaikummao S, Limpakarnjanarat K, Chantarojwong N, Mastro TD. HIV communication between husbands and wives: Effects on husband HIV testing in northern Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2007;8(2):313–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marín BV, Tschann JM, Gómez CA, Gregorich S. Self-efficacy to use condoms in unmarried Latino adults. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1998;26(1):53–71. doi: 10.1023/a:1021882107615. doi:10.1023/A:1021882107615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuiston C, Gordon A. The timing is never right: Mexican views of condom use. Health Care for Women International. 2000;21(4):277–290. doi: 10.1080/073993300245140. doi:10.1080/073993300245140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group TP. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine. 2009;6(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore J, Harrison JS, Kay KL, Deren S, Doll LS. Factors associated with Hispanic women's HIV-related communication and condom use with male partners. AIDS Care. 1995;7(4):415–428. doi: 10.1080/09540129550126371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales-Alemán MM, Hageman K, Gaul ZJ, Le B, Paz-Bailey G, Sutton MY. Intimate partner violence and human immunodeficiency virus risk among black and Hispanic women. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2014;47(6):689–702. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.08.007. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2014.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno CL, El-Bassel N. Dominican and Puerto Rican women in partnerships and their sexual risk behaviors. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2007;29(3):336–348. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Health Quality assessment tool for observational cohort and cross-sectional studies. 2014 Retrieved from http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-pro/guidelines/in-develop/cardiovascular-risk-reduction/tools/cohort.

- Noar SM, Carlyle K, Cole C. Why communication is crucial: Meta-analysis of the relationship between safer sexual communication and condom use. Journal of Health Communication. 2006;11(4):365–390. doi: 10.1080/10810730600671862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orengo-Aguayo R, Pérez-Jiménez D. Impact of relationship dynamics and gender roles in the protection of HIV discordant heterosexual couples: An exploratory study in the Puerto Rican context. Puerto Rico Health Sciences Journal. 2009;28(1):30–39. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Jimenez D, Seal DW, Serrano-Garcia I. Barriers and facilitators of HIV prevention with heterosexual Latino couples: Beliefs of four stakeholder groups. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2009;15(1):11–17. doi: 10.1037/a0013872. doi:10.1037/a0013872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulerwitz J, Dworkin S. Give-and-take in safer sex negotiations: The fluidity of gender-based power relations. Sexuality Research and Social Policy. 2006;3(3):40–51. [Google Scholar]

- Saul J, Norris FH, Bartholow KK, Dixon D, Peters M, Moore J. Heterosexual risk for HIV among Puerto Rican women: Does power influence self-protective behavior? AIDS And Behavior. 2000;4(4):361–371. doi: 10.1023/A:1026402522828. doi:10.1023/A:1026402522828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sionéan C, DiClemente RJ, Wingood GM, Crosby R, Cobb BK, Harrington K, Oh MK. Psychosocial and behavioral correlates of refusing unwanted sex among African-American adolescent females. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;30(1):55–63. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00318-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: Updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2005;52(5):546–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]