Abstract

Global ischemia following cardiac arrest is characterized by high mortality and significant neurological deficits in long-term survivors. Its mechanisms of neuronal cell death have only partially been elucidated. 12/15-lipoxygenase (12/15-LOX) is a major contributor to delayed neuronal cell death and vascular injury in experimental stroke, but a possible role in brain injury following global ischemia has to date not been investigated. Using a mouse bilateral occlusion model of transient global ischemia which produced surprisingly widespread injury to cortex, striatum, and hippocampus, we show here that 12/15-LOX is increased in a time-dependent manner in vasculature and neurons of both cortex and hippocampus. Furthermore, 12/15-LOX co-localized with apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF), a mediator of non-caspase related apoptosis in the cortex. In contrast, caspase-3 activation was more prevalent in the hippocampus. 12/15-lipoxygenase knockout mice were protected against global cerebral ischemia compared to wild-type mice, accompanied by reduced neurologic impairment. The lipoxygenase inhibitor LOXBlock-1 similarly reduced neuronal cell death both when pre-administered, and when given at a therapeutically relevant time point one hour after onset of ischemia. These findings suggest a pivotal role for 12/15-LOX in both caspase-dependent and caspase-independent apoptotic pathways following global cerebral ischemia, and suggest a novel therapeutic approach to reduce brain injury following cardiac arrest.

Keywords: global cerebral ischemia, lipoxygenase, apoptosis, hippocampus, cortex, cardiac arrest

Introduction

Global ischemia to the brain contributes significantly to the high mortality and morbidity following prolonged cardiac arrest. It is estimated that over 300,000 die each year, and of the survivors of cardiopulmonary resuscitation, most have severe residual defects[1–3]. Therapeutic hypothermia is protective in animal studies [4] and has been introduced clinically as treatment, but following the recent TTM trial its value beyond that of general temperature control has been drawn into question[5]. The brain as the organ most reliant on continuous oxygen and energy supply is considered the most vulnerable target in global ischemia. Ischemia-related oxygen and glucose deprivation of brain tissue triggers many cellular mechanisms, including excitoxicity, apoptosis, oxidative stress, and neuroinflammation [6]. Oxidative stress is one of the most important factors that exacerbate brain damage by reperfusion in global cerebral ischemia [7]. Among the proteins mediating oxidative stress, 12/15-lipoxygenase (12/15-LOX) is an important contributor to cell death in stroke-related brain ischemia. 12/15-LOX increases injury following transient focal ischemia [8–11]. Our group also showed that, besides reductions in infarct size, inhibition of 12/15-LOX also leads to reduced edema formation and blood – brain barrier leakage [11, 10]. A possible role for 12/15-LOX in global cerebral ischemia has not been investigated to date. We have recently introduced LOXBlock-1 as a novel non-antioxidant inhibitor of 12/15-LOX[12, 13]. LOXBlock-1 protected both cultured neurons and oligodendrocyte precursors against oxidative stress-related toxicity [12]. In a mouse model of transient focal ischemia, it was robustly neuroprotective, providing sustained protection over two weeks[13]. In the present study we tested our hypothesis that 12/15-LOX contributes to brain damage after global cerebral ischemia induced by transient bilateral occlusion of the carotid arteries, a widely used model of the brain injury sustained following cardiac arrest. The present study was also designed to address the question whether LOXBlock-1 could protect against transient global ischemia by inhibiting the 12/15-LOX pathway. We here show robust protection by LOXBlock-1, confirming the 12/15-LOX injury mechanism as being targetable, and expanding the indications where inhibitors of 12/15-LOX can be tested clinically.

Methods

Mouse transient global ischemia

All experiments are performed following an institutionally approved protocol in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. 12 to 16 week old male CD1 mice, or 12/15-LOX knockout mice (ALOX15(−/−) genotype) along with the corresponding C57Bl6J wild type controls, were subjected to transient forebrain ischemia as described previously[14–18]. Treatment with LOXBlock-1was by intraperitoneal injection of 50 mg/kg LOXBlock-1 dissolved in DMSO, 5 minutes before or one hour after onset of global cerebral ischemia (GCI). Weights and core temperatures of the mice were recorded before the surgical procedure, and anesthesia was induced with isoflurane (2.0 % induction, 1.5% maintenance) in a mixture of 70% nitrous oxide and 30% oxygen. Rectal temperature was maintained at 37.5±0.5°C using a feedback heating pad, and regional cerebral blood flow was monitored during the surgical procedure using a Laser Doppler Flowmeter. Afterwards, the trachea was intubated with a 20-G catheter and the lungs were mechanically ventilated as previously described[15].

Neuroscore assessment

The mice were individually tested in a quiet room 72 hours after forebrain ischemia. To measure the functional neurological condition of post-ischemic animals the neurological examinations were carried out according to an established Neuroscore [19, 20]. The score was determined by an investigator blinded to the pharmacological treatment or genotype of the animals.

Fluoro-Jade B Staining

Fluoro-Jade is an anionic fluorochrome capable of selectively staining degenerating neurons in brain slices. Fluoro-Jade is a simple, sensitive and reliable method for staining degenerating neurons and their processes [21]. 20 μm thick coronal brain sections were mounted on 2% gelatine-coated slides and dried. Slides were then immersed in a solution containing 1% sodium hydroxide in 80% alcohol for 5 min, followed by 2 min incubation in 70% alcohol and 2 min rinse in distilled water. The slides were transferred to a solution of 0.06% potassium permanganate for 10 min, and subsequently rinsed in distilled water for 2 min. After 20 min in the staining solution containing 0.0004% Fluoro-Jade B (Histo-Chem Inc., Jefferson, USA), the slides were rinsed three times for 1 min in distilled water. Excess water was removed by draining the slides vertically on a paper towel. The slides were then placed on a slide warmer (50°C; 5–10 min). The dry slides were xylene-cleared (at least 1 min) and coverslipped with DPX, non-fluorescent mounting medium[21]. All Fluoro-Jade B positive cells were counted at the CA1 region of the hippocampus bilaterally. For cell counts in the cortex, 6 different region of the brain cortex (superior to hippocampus, superolateral to hippocampus and lateral to the hippocampus, bilaterally) were evaluated. In the striatum, all Fluoro-Jade B positive cells were counted at 40× magnification. All cell counts were determined by an investigator blinded to the pharmacological treatment or genotype of the animals.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed on formalin-fixed sections, according to[9]. Brains were perfused transcardially first with ice cold PBS, then with 4% formalin. Following rapid removal and overnight storage in 4% formalin, brains were transferred to buffer containing 15% sucrose for 24 hours, then 30% sucrose. 20 μm sections are cut on a freezing microtome. After staining with primary antibodies (an affinity-purified antiserum raised against the C-terminus of 12/15-LOX in rabbits[13], antibodies to AIF (D-20, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX), activated caspase-3 (Asp-175, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), and fluorescent-tagged secondary antibodies, sections were analyzed on a Nikon Eclipse Ti fluorescent microscope equipped with NIS Elements software. For co-localization studies, a Zeiss LSM 5 Pascal scanning confocal microscope was used.

Combining Fluoro-Jade B with immunofluorescent staining

The Fluoro-Jade B histological processing was the same as described above except the time in potassium permanganate solution was reduced to 3–5 minutes[21, 22]. Immunohistochemistry for LOX was performed on tissue sections first treated with basic alcohol and aqueous potassium permanganate according to[9]. Slides were then placed in the Fluoro-Jade B staining solution and processed as previously described[22].

Statistical analysis

For two-group comparisons, the Student’s test was used. If the data did not follow a normal distribution, as well as for non-parametric ordinal data, we employed the Mann-Whitney U-test. P values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Widespread injury to cortex and hippocampus following transient global cerebral ischemia

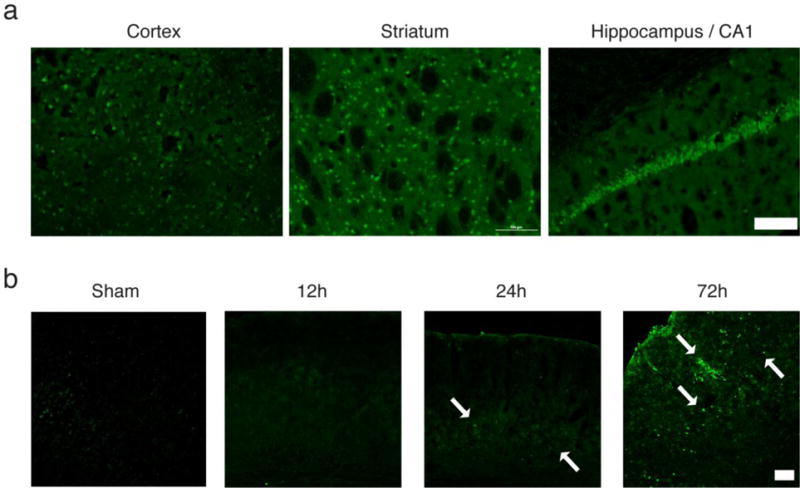

To demonstrate injury following transient global ischemia, we used Fluoro-Jade B as damage marker, known to label injured neurons [23]. We initially tested a transient bilateral occlusion model of global ischemia with 12 minutes of ischemia, but found damage 72 hours later to be fairly variable, as has previously been suggested[24]. In contrast, 20 minutes of global ischemia gave consistent neurological injury, and was thus used for the remainder of our study. Surprisingly, we found widespread injury not just in the hippocampus, which is known to be particularly susceptible to injury, but also in cortex and striatum (Figure 1a). This has been noted before[25], but many studies restrict their analysis to the hippocampal formation. Based on our findings here, we took a broader focus and studied the effects of GCI on cortex and striatum, along with the hippocampus.

Fig. 1.

Widespread injury to the brain following GCI and time-dependent increase of 12/15-LOX. a) At 72 hours after 20 minutes of GCI, Fluoro-Jade staining indicates damaged neurons throughout the brain, including cortex, striatum, and hippocampus, specifically the CA1 formation. Scale Bar, 200 μm. b) Immunostaining shows a time-dependent up-regulation of 12/15-LOX in the cortex (arrows). Scale Bar, 100μm

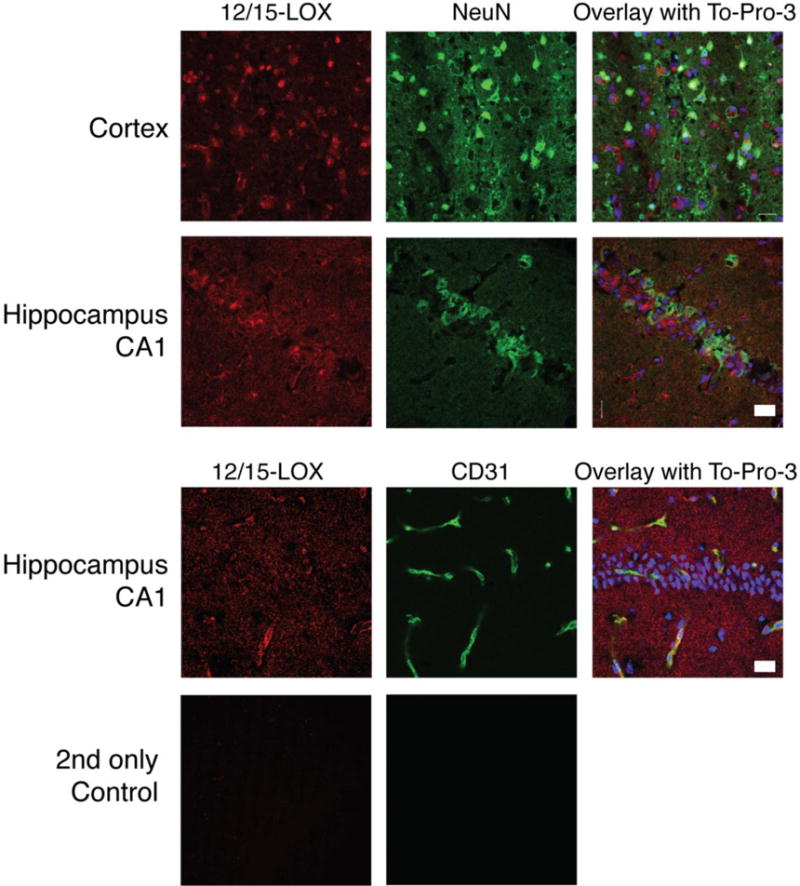

Lipoxygenase expression in mouse brain tissue

Immunostaining for 12/15-LOX in brain sections taken at different times following 20 minutes of global ischemia showed a time-dependent increase up to 72 hours (Figure 1b). This delayed increase in 12/15-LOX expression is consistent with a role for 12/15-LOX in causing post ischemic injury, as seen in focal ischemia models[10, 9]. To confirm which cells exhibit the increased amounts of 12/15-LOX staining we performed double staining with an antibody directed against the neuronal marker, NeuN. In cortex and CA1 region of the hippocampus, most of the LOX staining was associated with neurons (Figure 2). In addition some of the 12/15-LOX signal was detected in cells labeled with the endothelial cell marker CD31, shown here for the hippocampus (Figure 2, lower panel). No immunoreactivity was detected when the primary antibody was omitted.

Fig. 2.

12/15-LOX protein is expressed neurons in both cortex and hippocampal CA1 region, and also in endothelial cells in the hippocampus. The neuronal marker NeuN partially overlapped with the 12/15-LOX signal in both cortex and hippocampal CA1 region, whereas 12/15-LOX also showed partial costaining with the endothelial cell marker CD31 in the hippocampus. An overlay with the nuclear marker To-Pro-3 indicates the localization of the hippocampal CA1 neurons. At bottom, omitting the primary antibodies abolished the signal. Scale Bar, 20μm

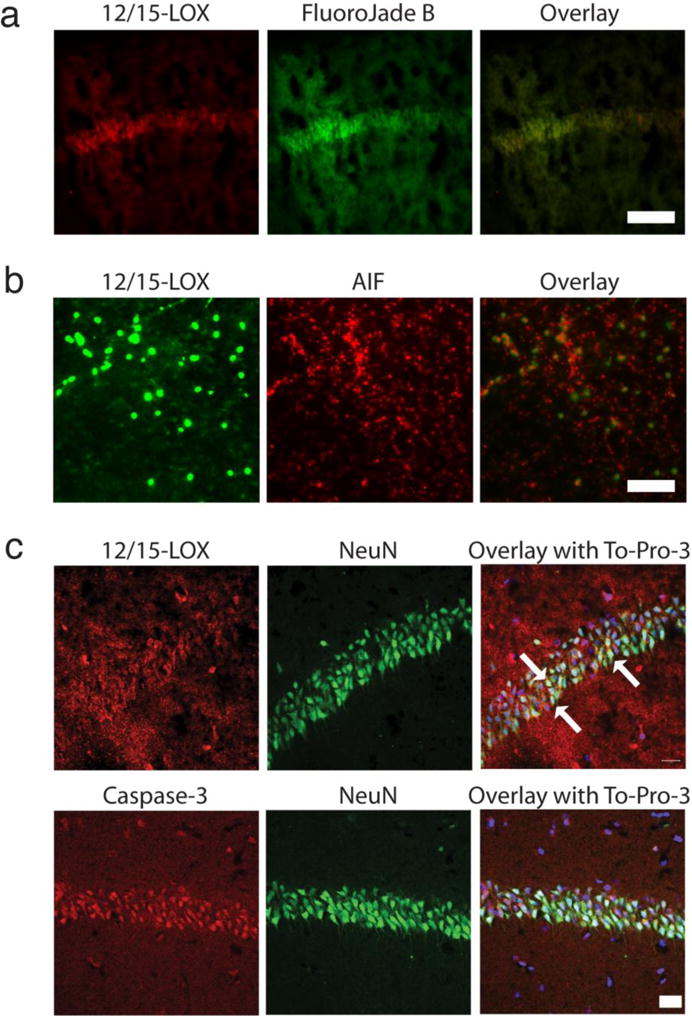

Fluoro-Jade B stained cells in the hippocampal CA1 region were also 12/15-LOX positive

To establish a more direct connection between 12/15-LOX expression and neuronal cell death, we incubated Fluoro-Jade B stained sections with 12/15-LOX antibody. Strikingly, Fluoro-Jade B positive cells in the CA1 region also stained for 12/15-LOX (Figure 3a), suggesting detrimental effects of increased 12/15-LOX expression.

Fig. 3.

12/15-LOX costaining with the neuronal damage marker Fluoro-Jade B and with markers for apoptosis. a) 12/15-LOX staining in Fluoro-Jade-treated tissue partially overlaps with the Fluoro-Jade B signal in the hippocampal CA1 region. Scale Bar, 100μm. b) In the cortex, 12/15-LOX staining ovelaps with the apoptosis-inducing factor AIF, a marker for caspase-independent apoptosis. Scale Bar, 100μm. c) The hippocampus shows increased 12/15-LOX following global ischemia, with higher apparent levels in the CA1 region, where 12/15-LOX partially coincides with NeuN (arrows). Activated caspase-3 in the CA1 formation is present in NeuN-expressing cells, suggesting some 12/15-LOX positive cells may also feature activated caspase-3. Scale Bar, 20μm

AIF staining/Caspase-3 staining

In a first attempt at studying cell death mechanisms through 12/15-LOX in the GCI model, we co-stained for 12/15-LOX and apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF), which is a caspase-independent pathway of cell death. 12/15-LOX expressing cells in the cortex also express high levels of apoptosis-inducing factor AIF (Figure 3b). In the hippocampus we did not see strong AIF staining, despite increased 12/15-LOX expression (data not shown). Conversely, activated caspase-3 was mostly absent from the cortex but clearly detected in the hippocampal CA1 region, as expected from previous studies of global ischemia[26]. To identify nuclei in the CA1 region of the hippocampus, we co-stained with the nuclear dye To-Pro-3, and most of the activated caspase-3 thus appeared to localize to the nucleus (Figure 3c). 12/15-LOX in the hippocampus was more widely distributed, with only some of the signal associated with the CA1 neurons (Arrows in Figure 3c). Unfortunately, we could not perform the direct co-localization of caspase-3 with 12/15-LOX, because both antibodies were raised in rabbit. Nonetheless, the staining pattern suggested strong caspase-3 activation in the CA1 neurons, and a partial overlap with increased 12/15-LOX signal, which was more widely distributed throughout the hippocampus (Figure 3c).

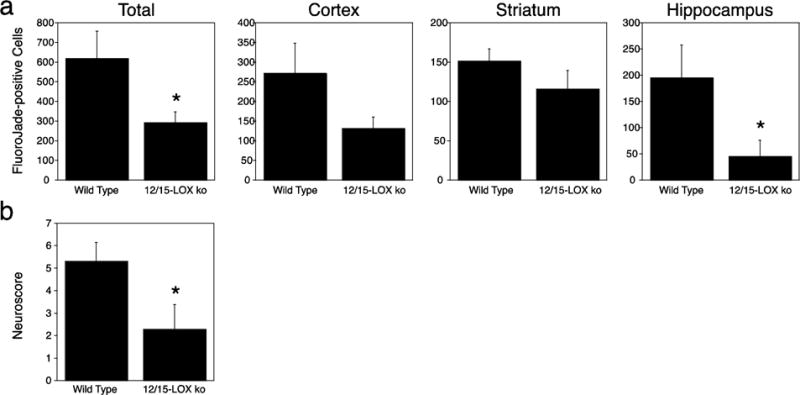

12/15-LOX ko mice show less neuronal injury and an improved behavioral score

For a more quantifiable determination of damaging effects of 12/15-LOX following GCI, we compared mice in which the ALOX15 gene had been deleted (12/15-LOX ko mice)[27] to the corresponding wild-types for brain injury 72 hours after 20 minutes of GCI. Blood flow measured by Laser Doppler Flowmeter was consistently reduced to less than 20% of the baseline value, with averages of 12.41 ± 0.84 for the wild type mice and 11.38 ± 1.19 for the knockouts. According to Fluoro-Jade B staining data (Figure 4a), the 12/15-LOX knockout mice showed a significantly reduced number of Fluoro-Jade B positive cells (p=0.015). The hippocampus appeared to show the highest level of protection, but in all three individual brain regions evaluated (cortex, striatum, and hippocampus) there were less FJ-positive cells in the knockout mouse brains compared to wild type, suggesting the protective effect is not restricted to any one area. Three days after the global ischemia, we also tested the mice for their performance in a 14-point neuroscore assessment[20, 19]. The knockout mice achieved a significantly better neuroscore, suggesting that they were protected against GCI by the absence of 12/15-LOX expression (Figure 4b).

Fig. 4.

12/15-LOX knockout mice show less damage and an improved neuroscore following GCI. a) 72 hours after 20 minutes of GCI, 12/15-LOX ko mice exhibited lower numbers of Fluoro-Jade B-positive cells. b) The reduced injury was reflected in an improved neuroscore compared to wild-type mice (n=21 for wild type, n=16 for 12/15-LOX ko)

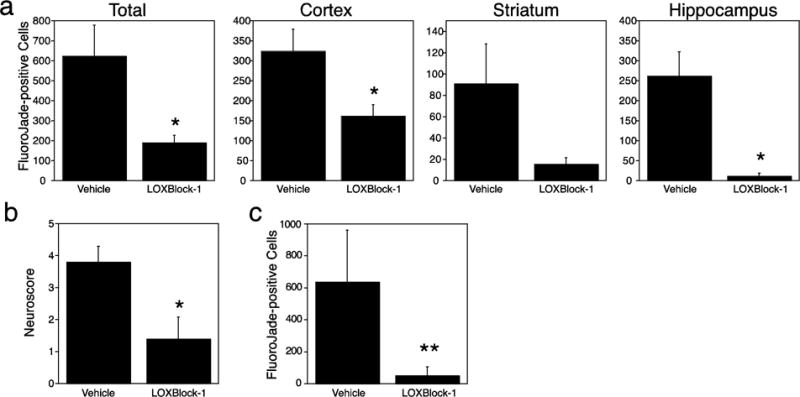

Pharmacological inhibition of 12/15-LOX reduces injury in the global ischemia model, accompanied by an improved neuroscore

The preceding results suggested to us that blocking 12/15-LOX activity in mice subjected to GCI may be beneficial. We thus tested if pharmacological inhibition by the 12/15-LOX inhibitor LOXBlock-1[12, 13] would protect against GCI in vivo. Intraperitoneal injection of 50mg/kg LOXBlock-1, 5 minutes before induction of global cerebral ischemia reduced Fluoro-Jade staining at 72 hours, compared to vehicle-treated mice (Figure 5a). Again, lower numbers of Fluoro-Jade B-positive cells were found in each brain region studied, with the differences in the cortex and hippocampus reaching statistical significance. This reduced injury in LOXBlock-1 treated mice was also reflected in an improved neurological score (Figure 5b). We then repeated the study with administration of LOXBlock-1 one hour after onset of ischemia. When given at this therapeutically relevant time point, neuronal cell death again was significantly reduced (Figure 5c).

Fig. 5.

Pharmacologic inhibition of 12/15-LOX protects mice against GCI. a) Treatment with LOXBlock-1 reduced neuronal injury, as detected by Fluoro-Jade B staining in mice 72 hours after 20 minutes of GCI. b) This was accompanied by an improved neuroscore (n=7 for vehicle, n=7 for LOXBlock-1). c) LOXBlock-1 still reduced neuronal cell death when given one hour after onset of ischemia (n=11 for vehicle, n=12 for LOXBlock-1).

Discussion

The major finding of our study is the widespread up-regulation of 12/15-LOX following GCI, which contributes to neuronal cell death and neurological deficits. Expression levels gradually increased over time, and were high in cortex, striatum, and hippocampus at 72 hours after 20 minutes of global ischemia. Global cerebral ischemia is caused by a deficiency of blood supply to the brain which results in delayed neuronal cell death in selective regions of the brain. Cerebral cortex, the hippocampus, and striatum are commonly affected [25]. Nonetheless, many studies focus specifically on regions seen as selectively vulnerable, especially the hippocampal CA1 region[28]. Protective astrocyte functions have been seen as one cause for differential vulnerability[29]. We have not specifically studied astrocyte involvement in the current study, because the increased expression of 12/15-LOX was seen predominantly in neurons and endothelial cells, as we have also found in previous studies of focal ischemia[10, 13]. This however, does not rule out that astrocytes may modulate the effects of 12/15-LOX in different brain regions, e.g., through secretion of neurotrophic factors. In our model the cortex is affected along with striatum and hippocampus. This may reflect the severity of 20 minutes of global ischemia; similarly, spiny neurons in the striatum were heavily affected in a GCI model with 22 minutes bilateral occlusion [30]. We therefore evaluated neuronal injury separately in cortex, striatum, and hippocampus, to ensure the reliability of our results. The trends in all cases were similar, with less cell damage occurring in all regions when 12/15-LOX activity was reduced, either by gene knockout (Figure 4) or using the 12/15-LOX inhibitor (Figure 5).

With oxygen and substrate deficiency, disturbance in ionic hemostasis and enzymatic lipolysis results in damage to membrane structure [31]. Previous studies in gerbils have shown an increase in both lipid peroxidation and the concentration of malondialdehyde (MDA) as oxidative stress marker. This occurred through a period of 1 to 4 days in hippocampus, cerebral cortex and striatum after global cerebral ischemia, and was preceded by a drop in reduced glutathione [32]. 12/15-LOX is activated when glutathione levels drop[33] and, because 12/15-LOX oxidizes polyunsaturated fatty acids directly in membranes, it is a major source for lipid peroxides and MDA. Several oxidative stress mechanisms have been investigated in global cerebral ischemia studies, notably superoxide dismutase, cyclooxygenase activation, and nitric oxide signaling. In contrast, the relatively novel 12/15-LOX pathway of neuronal and vascular damage has not been studied in this context. Considering an important role for 12/15-LOX in mediating oxidative stress-related damage in transient focal ischemia has been demonstrated by us and others[8, 10, 11], it was timely to analyze the effects of 12/15-LOX and its inhibition in a global cerebral ischemia model.

And yet, even in our study there are apparent differences relating to the mode of cell death. While caspase-3 activation is seen mostly in the CA1 region as previously observed [34, 35], the cortex features mostly increased AIF, a mediator of non-caspase related apoptosis. 12/15-LOX localizes to cells with increased AIF staining in the cortex, similar to what is seen in transient focal ischemia[9, 36] and indicative of a direct connection between 12/15-LOX up-regulation and AIF-related apoptosis. The overlap between 12/15-LOX and activated caspase-3 in the CA1 formation is less clear, in part because both antibodies used were raised in rabbits and so could not be used simultaneously. Because some of the increased 12/15-LOX in the hippocampus labels CD31-positive endothelial cells (Figure 2), while caspase-3 is mostly activated in neurons, the damaging effects of 12/15-LOX in the hippocampus may be more indirect. One advantage of using Fluoro-Jade as injury marker is that it results in very clear cellular staining, so that counting labeled cells gives a reliable measure of neuronal injury[22]. However, because it specifically labels damaged neurons, we cannot rule out vascular damage, which appears likely based on the mostly vascular staining pattern in the hippocampus for 12/15-LOX.

AIF is a well-known mediator of apoptosis, and a key component of the parthanatos cascade, a caspase-independent pathway of cell death[37]. AIF is a mitochondrial protein, which translocates to the nucleus in a calpain-dependent manner in the course of cellular injury[38, 39]. Our previous studies in neuronal HT22 cells have shown that the cytosolic 12/15-LOX initially binds to mitochondrial membranes, and co-localizes with AIF in the nucleus at later stages[40, 9, 41]. In focal ischemia studies, this was typically seen as an overall increase of immunoreactivity in affected neurons, with mostly nuclear localization after 24 hours[9]. Our results show that some of the 12/15-LOX expressing cells in the cortex after GCI strongly stain positive for AIF, suggesting a possible role for this cell death mechanism in GCI[42]. This is novel, because most studies focused on hippocampal CA1 neuronal cell death report caspase-mediated cell death as a dominant mechanism in global cerebral ischemia[43]. Accordingly, it seems that AIF plays an important role for delayed neuronal cell death in the cortex after GCI. In contrast, Thal et al. (Plesnila) found significant levels of AIF also in the hippocampus after GCI[44]. We instead detected mostly activated caspase-3, as has been commonly noted in the literature. It may thus be that in the hippocampus, the apoptotic pathway chosen depends on the method of inducing GCI, especially the severity of the insult. In rats, the Steinberg group reported increased levels of both AIF in focal ischemia[36], and cytochrome c indicating caspase-related apoptosis in global ischemia [45], again suggesting that the mode of apoptosis depends on the specific model used. 12/15-LOX as an early disruptor of the mitochondrial membrane may be important for both of these events. Clearly, whether or not 12/15-LOX in the hippocampus contributes directly or indirectly to neuronal cell death, it is crucial; both knockout and pharmacological inhibition provided excellent protection to the hippocampus (see Figures 4a and 5a).

We have recently introduced a novel non-antioxidant inhibitor of 12/15-LOX, LOXBlock-1[12, 13]. Originally identified in a computer screen as an active site-directed inhibitor of human 12/15-LOX, LOXBlock-1 inhibits the human 12/15-LOX in vitro[46], and protects neurons and oligodendrocytes against oxidative stress-related cell death[12]. In transient focal ischemia, LOXBlock-1 is as efficient as the antioxidant 12/15-LOX inhibitor baicalein[11], but at much lower doses (50 vs 300 mg/kg)[13, 41]. Because it fits into the active site of 12/15-LOX and lacks antioxidant activity, LOXBlock-1 most likely functions through direct inhibition of 12/15-LOX. Although mild hypothermia is known to protect against cardiac arrest-induced injury [4], at present there is no pharmacological agent available. According to our results, LOXBlock-1 prevented both histological and neurobehavioral abnormalities in mice subjected to global cerebral ischemia. Further studies are needed to determine its effect on long-term outcome. Likewise, optimal dosage, timing, and route of administration still need to be determined, but our current findings suggest that 12/15-LOX inhibition is neuroprotective against GCI.

Besides 12/15-LOX, other targets for possible therapeutic intervention have recently emerged. In one approach, Dawson and colleagues found that miR-223 regulates glutamate receptor expression and thus limits excitotoxicity following GCI[17]. The group of Guohua Xi showed that gene knockout of the thrombin receptor Protease Activated Receptor-1 (PAR-1) reduces injury after GCI[47]. This was accompanied by a reduction in map kinase signaling, but a therapeutic strategy to exploit this pathway remains to be demonstrated. Another target that may be more malleable is the loss of glutathione in global ischemia: Swanson and colleagues[48] have shown in an elegant study that supplementation with the antioxidant N-acetyl cysteine (NAC) may lead to a stabilization of neuronal glutathione levels, accompanied by reduced injury. The mechanism behind the protection afforded may well be a reduction of 12/15-LOX activity, as the loss of glutathione is a major step in 12/15-LOX activation in both neurons and oligodendrocytes[33, 49]. Similarly, several antioxidants have shown protection, in part through lowering matrix metalloproteinase activity[50, 51], and again 12/15-LOX involvement should not be ruled out.

In summary, our results show that 12/15-LOX is up-regulated following GCI, and contributes to neuronal injury. Either gene knockout or treatment with the 12/15-LOX inhibitor LOXBlock-1 reduce injury and improve neurological outcome, suggesting 12/15-LOX inhibition may be a novel therapeutic approach to reduce brain damage following GCI.

Acknowledgments

Support through grants from the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH R01NS049430, R01NS069939, and R21NS087165 to K.v.L.) is gratefully acknowledged.

Funding: Support through grants from the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH R01NS049430, R01 NS069939, and R21NS087165 to K.v.L.) is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval: All applicable international, national, and institutional guidelines for the care and use of animals were followed.

References

- 1.Nadkarni V, Larkin G, Peberdy M, Carey S, Kaye W, Mancini M, et al. First documented rhythm and clinical outcome from in-hospital cardiac arrest among children and adults. JAMA. 2006;295:50–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eisenberg M, Mengert T. Primary care: cardiac resuscitation. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1304–13. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104263441707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roine R, Kajaste S, Kaste M. Neuropsychological sequelae of cardiac arrest. JAMA. 1993;269:237–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dietrich W, Kuluz J. New research in the field of stroke: therapeutic hypothermia after cardiac arrest. Stroke. 2003;34:1051–3. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000061885.90999.A9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nielsen N, Wetterslev J, Cronberg T, Erlinge D, Gasche Y, Hassager C, et al. Targeted temperature management at 33 degrees C versus 36 degrees C after cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(23):2197–206. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1310519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kirino T. Delayed neuronal death. Neuropathology. 2000;20(Suppl):S95–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1789.2000.00306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kitagawa K, Matsumoto M, Oda T, Niinobe M, Hata R, Handa N, et al. Free radical generation during brief period of cerebral ischemia may trigger delayed neuronal death. Neuroscience. 1990;35(3):551–8. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(90)90328-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khanna S, Roy S, Slivka A, Craft TK, Chaki S, Rink C, et al. Neuroprotective properties of the natural vitamin E alpha-tocotrienol. Stroke. 2005;36(10):2258–64. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000181082.70763.22. 01.STR.0000181082.70763.22 [pii] 10.1161/01.STR.0000181082.70763.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pallast S, Arai K, Pekcec A, Yigitkanli K, Yu Z, Wang X, et al. Increased nuclear apoptosis-inducing factor after transient focal ischemia: a 12/15-lipoxygenase-dependent organelle damage pathway. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2010;30(6):1157–67. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.281. jcbfm2009281 [pii] 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jin G, Arai K, Murata Y, Wang S, Stins MF, Lo EH, et al. Protecting against cerebrovascular injury: contributions of 12/15-lipoxygenase to edema formation after transient focal ischemia. Stroke. 2008;39(9):2538–43. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.514927. STROKEAHA.108.514927 [pii] 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.514927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Leyen K, Kim HY, Lee SR, Jin G, Arai K, Lo EH. Baicalein and 12/15-lipoxygenase in the ischemic brain. Stroke. 2006;37(12):3014–8. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000249004.25444.a5. 01.STR.0000249004.25444.a5 [pii] 10.1161/01.STR.0000249004.25444.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Leyen K, Arai K, Jin G, Kenyon V, Gerstner B, Rosenberg PA, et al. Novel lipoxygenase inhibitors as neuroprotective reagents. J Neurosci Res. 2008;86(4):904–9. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yigitkanli K, Pekcec A, Karatas H, Pallast S, Mandeville E, Joshi N, et al. Inhibition of 12/15-lipoxygenase as therapeutic strategy to treat stroke. Ann Neurol. 2013;73(1):129–35. doi: 10.1002/ana.23734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee SR, Lok J, Rosell A, Kim HY, Murata Y, Atochin D, et al. Reduction of hippocampal cell death and proteolytic responses in tissue plasminogen activator knockout mice after transient global cerebral ischemia. Neuroscience. 2007;150(1):50–7. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.06.029. S0306-4522(07)00786-5 [pii] 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhen G, Dore S. Optimized protocol to reduce variable outcomes for the bilateral common carotid artery occlusion model in mice. J Neurosci Methods. 2007;166(1):73–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2007.06.029. S0165-0270(07)00339-1 [pii] 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2007.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murakami K, Kondo T, Kawase M, Chan PH. The development of a new mouse model of global ischemia: focus on the relationships between ischemia duration, anesthesia, cerebral vasculature, and neuronal injury following global ischemia in mice. Brain Res. 1998;780:304–10. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)01217-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harraz MM, Eacker SM, Wang X, Dawson TM, Dawson VL. MicroRNA-223 is neuroprotective by targeting glutamate receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(46):18962–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121288109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Traystman RJ. Animal models of focal and global cerebral ischemia. ILAR J. 2003;44(2):85–95. doi: 10.1093/ilar.44.2.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thal SC, Thal SE, Plesnila N. Characterization of a 3-vessel occlusion model for the induction of complete global cerebral ischemia in mice. J Neurosci Methods. 2010;192(2):219–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2010.07.032. S0165-0270(10)00407-3 [pii] 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2010.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McGraw CP. Experimental cerebral infarctioneffects of pentobarbital in Mongolian gerbils. Arch Neurol. 1977;34(6):334–6. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1977.00500180028006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmued LC, Albertson C, Slikker W., Jr Fluoro-Jade: a novel fluorochrome for the sensitive and reliable histochemical localization of neuronal degeneration. Brain Res. 1997;751(1):37–46. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(96)01387-x. doi:S0006-8993(96)01387-X [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmued LC, Hopkins KJ, Fluoro-Jade B. a high affinity fluorescent marker for the localization of neuronal degeneration. Brain Res. 2000;874(2):123–30. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02513-0. doi:S0006-8993(00)02513-0 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ehara A, Ueda S. Application of Fluoro-Jade C in acute and chronic neurodegeneration models: utilities and staining differences. Acta Histochem Cytochem. 2009;42:171–9. doi: 10.1267/ahc.09018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kristian T, Hu B. Guidelines for using mouse global cerebral ischemia models. Transl Stroke Res. 2013;4(3):343–50. doi: 10.1007/s12975-012-0236-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pulsinelli WA, Brierley JB, Plum F. Temporal profile of neuronal damage in a model of transient forebrain ischemia. Ann Neurol. 1982;11(5):491–8. doi: 10.1002/ana.410110509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen J, Nagayama T, Jin K, Stetler RA, Zhu RL, Graham SH, et al. Induction of caspase-3-like protease may mediate delayed neuronal death in the hippocampus after transient cerebral ischemia. J Neurosci. 1998;18(13):4914–28. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-13-04914.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sun D, Funk CD. Disruption of 12/15-lipoxygenase expression in peritoneal macrophages. Enhanced utilization of the 5-lipoxygenase pathway and diminished oxidation of low density lipoprotein. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(39):24055–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nitatori T, Sato N, Waguri S, Karasawa Y, Araki H, Shibanai K, et al. Delayed neuronal death in the CA1 pyramidal cell layer of the gerbil hippocampus following transient ischemia is apoptosis. J Neurosci. 1995;15(2):1001–11. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-02-01001.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ouyang YB, Voloboueva LA, Xu LJ, Giffard RG. Selective dysfunction of hippocampal CA1 astrocytes contributes to delayed neuronal damage after transient forebrain ischemia. J Neurosci. 2007;27(16):4253–60. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0211-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yoshioka H, Niizuma K, Katsu M, Sakata H, Okami N, Chan PH. Consistent injury to medium spiny neurons and white matter in the mouse striatum after prolonged transient global cerebral ischemia. J Neurotrauma. 2011;28(4):649–60. doi: 10.1089/neu.2010.1662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Islekel H, Islekel S, Guner G, Ozdamar N. Evaluation of lipid peroxidation, cathepsin L and acid phosphatase activities in experimental brain ischemia-reperfusion. Brain Res. 1999;843:1–2. 18–24. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01845-4. doi:S0006-8993(99)01845-4 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Candelario-Jalil E, Mhadu NH, Al-Dalain SM, Martinez G, Leon OS. Time course of oxidative damage in different brain regions following transient cerebral ischemia in gerbils. Neurosci Res. 2001;41(3):233–41. doi: 10.1016/s0168-0102(01)00282-6. doi:S0168010201002826 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li Y, Maher P, Schubert D. A role for 12-lipoxygenase in nerve cell death caused by glutathione depletion. Neuron. 1997;19(2):453–63. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80953-8. doi:S0896-6273(00)80953-8 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tang XL, Takano H, Xuan YT, Sato H, Kodani E, Dawn B, et al. Hypercholesterolemia abrogates late preconditioning via a tetrahydrobiopterin-dependent mechanism in conscious rabbits. Circulation. 2005;112(14):2149–56. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.566190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harukuni I, Bhardwaj A. Mechanisms of brain injury after global cerebral ischemia. Neurologic clinics. 2006;24(1):1–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao H, Yenari MA, Cheng D, Barreto-Chang OL, Sapolsky RM, Steinberg GK. Bcl-2 transfection via herpes simplex virus blocks apoptosis-inducing factor translocation after focal ischemia in the rat. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2004;24(6):681–92. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000127161.89708.A5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang Y, Kim NS, Haince JF, Kang HC, David KK, Andrabi SA, et al. Poly(ADP-ribose) (PAR) binding to apoptosis-inducing factor is critical for PAR polymerase-1-dependent cell death (parthanatos) Sci Signal. 2011;4(167):ra20. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Joza N, Pospisilik JA, Hangen E, Hanada T, Modjtahedi N, Penninger JM, et al. AIF: not just an apoptosis-inducing factor. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1171:2–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cao G, Xing J, Xiao X, Liou AK, Gao Y, Yin XM, et al. Critical role of calpain I in mitochondrial release of apoptosis-inducing factor in ischemic neuronal injury. J Neurosci. 2007;27(35):9278–93. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2826-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pallast S, Arai K, Wang X, Lo EH, van Leyen K. 12/15-Lipoxygenase targets neuronal mitochondria under oxidative stress. J Neurochem. 2009;111(3):882–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06379.x. JNC6379 [pii] 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06379.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van Leyen K. Lipoxygenase: an emerging target for stroke therapy. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2013;12(2):191–9. doi: 10.2174/18715273112119990053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cao G, Clark RS, Pei W, Yin W, Zhang F, Sun FY, et al. Translocation of apoptosis-inducing factor in vulnerable neurons after transient cerebral ischemia and in neuronal cultures after oxygen-glucose deprivation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2003;23(10):1137–50. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000087090.01171.E7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chan P. Mitochondria and neuronal death/survival signaling pathways in cerebral ischemia. Neurochem Res. 2004;29:1943–9. doi: 10.1007/s11064-004-6869-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thal SE, Zhu C, Thal SC, Blomgren K, Plesnila N. Role of apoptosis inducing factor (AIF) for hippocampal neuronal cell death following global cerebral ischemia in mice. Neurosci Lett. 2011;499(1):1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhao H, Yenari MA, Cheng D, Sapolsky RM, Steinberg GK. Biphasic cytochrome c release after transient global ischemia and its inhibition by hypothermia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2005;25(9):1119–29. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kenyon V, Chorny I, Carvajal WJ, Holman TR, Jacobson MP. Novel human lipoxygenase inhibitors discovered using virtual screening with homology models. J Med Chem. 2006;49(4):1356–63. doi: 10.1021/jm050639j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang J, Jin H, Hua Y, Keep RF, Xi G. Role of protease-activated receptor-1 in brain injury after experimental global cerebral ischemia. Stroke. 2012;43(9):2476–82. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.661819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Won SJ, Kim JE, Cittolin-Santos GF, Swanson RA. Assessment at the single-cell level identifies neuronal glutathione depletion as both a cause and effect of ischemia-reperfusion oxidative stress. J Neurosci. 2015;35(18):7143–52. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4826-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang H, Li J, Follett PL, Zhang Y, Cotanche DA, Jensen FE, et al. 12-Lipoxygenase plays a key role in cell death caused by glutathione depletion and arachidonic acid in rat oligodendrocytes. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;20(8):2049–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03650.x. EJN3650 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee SR, Tsuji K, Lee SR, Lo EH. Role of matrix metalloproteinases in delayed neuronal damage after transient global cerebral ischemia. J Neurosci. 2004;24(3):671–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4243-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Park JW, Jang YH, Kim JM, Lee H, Park WK, Lim MB, et al. Green tea polyphenol (−)-epigallocatechin gallate reduces neuronal cell damage and up-regulation of MMP-9 activity in hippocampal CA1 and CA2 areas following transient global cerebral ischemia. J Neurosci Res. 2009;87(2):567–75. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]