Abstract

This study investigated the relationship between reinforcer value and choice between cocaine and two non-drug alternative reinforcers in rats. The essential value (a behavioral economic measure based on elasticity of demand) of intravenous cocaine and food (Experiment 1) or saccharin (Experiment 2) was determined in the first phase of each experiment. Food had higher essential value than cocaine, whereas the essential values of cocaine and saccharin did not differ. In the second phase of each experiment, rats were allowed to make mutually exclusive choices between cocaine and the non-drug alternative reinforcer. The main findings were that the essential value of cocaine was a positive predictor of cocaine preference and the essential value of food or saccharin was a negative predictor of cocaine preference. An analysis of within-session patterns of choice behavior revealed sequential dependencies, whereby rats were more likely to choose cocaine on a particular trial after having chosen the non-drug alternative on previous trials. When the time between choices was increased, these sequential dependencies disappeared. The results of these experiments are consistent with the suggestion that addiction-like behavior involves both overvaluation of drug reinforcers and undervaluation of non-drug reinforcers.

Keywords: Cocaine, demand, choice, essential value, saccharin, food, rats

INTRODUCTION

Recently, there has been much interest in studying rats’ choice of drug reinforcers over non-drug alternatives (Augier et al. 2012; Cantin et al. 2010; Caprioli et al. 2015; Huynh et al. 2015; Kerstetter & Kippin, 2011; Kerstetter et al. 2012; Lenoir et al. 2013; Madsen & Ahmed, 2015; Panlilio et al. 2015; Perry et al. 2013, 2015; Thomsen et al. 2013; Tunstall & Kearns, 2013, 2014, 2015; Tunstall et al. 2014; Vandaele et al. 2016; Vanhille et al. 2015). This interest has been stimulated by the observation that rats’ choice of drug over non-drug reinforcers more closely approximates addiction-like behavior than self-administration in the absence of alternatives (Ahmed, 2010). A common finding in choice studies with rats is that there are large individual differences in preference, with some rats consistently choosing the drug reinforcer and others consistently choosing the non-drug alternative.

Currently, little is known about what makes some rats prefer the drug and others prefer the non-drug alternative. Individual differences in the ways that rats value the two reinforcers available in a choice situation could account for individual differences in preference. For example, drug preferrers may value the drug reinforcer more highly than do non-drug-preferring rats, with there being no difference between these subsets of rats in terms of how they value the non-drug alternative. Alternatively, it may be that there is no difference between these rats in terms of how the drug is valued, but drug preferrers place lower value on the non-drug alternative than do non-drug preferrers. Either of these possibilities alone might be expected to lead to increased drug preference. Drug preference could be especially likely when both of these possibilities occur in the same subject. The goal of the present study was to determine how the values of drug and non-drug reinforcers contribute to the choice between them.

A behavioral economic approach was used to quantify reinforcer value. Hursh and Silberberg’s (2008) exponential demand model was applied to rats’ consumption of cocaine and non-drug alternative reinforcers. This model provides for any reinforcer a single measure, called essential value (EV), that reflects the inelasticity of demand for the reinforcer. The advantage of essential value over other measures of reinforcer strength is that it is independent of reward magnitude, dose, and other factors that have made measurement of reinforcer value difficult (Hursh & Silberberg, 2008). Progressive-ratio schedule breakpoint (BP), a commonly used measure of motivation for a reinforcer, has been shown to vary as a function of drug dose (e.g., Gancarz et al., 2012) or the magnitude of food (Skjoldager et al., 1993) or sucrose (Rickard et al., 2009) reinforcers. Because EV is not affected by scalar properties of the reinforcer in this way, it is thought to be a purer measure or reinforcer value. A growing number of recent studies have used the exponential demand model to quantify reinforcer value (e.g., Bentzley et al. 2013, 2014; Christensen et al. 2008a, 2008b; Koffarnus & Woods, 2013; Lamb & Daws, 2013; Schwartz et al. 2016).

In the present study, the drug reinforcer was cocaine and the non-drug alternative was food (Exp. 1), a reinforcer that is biologically necessary for survival, or saccharin (Exp. 2), a reinforcer that is not necessary for survival. In both experiments, the EVs of cocaine and the non-drug alternative were obtained for each rat in a first phase. In a second phase, rats’ preference for these reinforcers was measured in a choice situation. The primary goal of the present experiments was to investigate how reinforcer value relates to choice. It was hypothesized that increased cocaine EV or decreased non-drug alternative EV would be associated with increased cocaine preference.

A secondary goal of the present study was to investigate within-session patterns of choice behavior. Previous studies with non-drug reinforcers analyzing sequences of behavior have found that choices are often determined in part by previous choices (e.g, Shimp, 1966; Silberberg & Williams, 1974). These kinds of sequential dependencies indicate that choice behavior is influenced by local factors that are not always captured by whole-session measures of preference. We examined potential sequential dependencies here in an effort to more fully characterize the processes contributing to the choice between cocaine and non-drug alternatives.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Twenty-seven adult male Long-Evans rats completed Exp. 1 and 20 adult male Long-Evans rats completed Exp. 2. Rats were individually housed in plastic cages with wood-chip bedding. Rats in Exp. 1, where food was a reinforcer, were maintained at 85% of their free-feeding weights (approximately 400-500 grams) throughout the experiment. Rats in Exp. 2, where saccharin was the reinforcer instead of food, had unlimited access to rat chow in their homecages. Rats in both experiments had unlimited access to water in their homecages. Throughout the experiment, rats were treated in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Academy of Science, 2011) and all procedures were approved by American University’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Apparatus

Training in both experiments took place in 10 standard operant test chambers described in detail elsewhere (Tunstall & Kearns, 2014). The essential features of each chamber were two retractable levers, a food dispenser and food trough (Exp. 1) or retractable sipper tube and bottle (Exp. 2), cue-lights above each lever, and a speaker used to provide a tone (4000 Hz and 70 dB) stimulus. In both experiments, cocaine (Drug Supply Program, National Institute on Drug Abuse, Bethesda, MD) in a saline solution at a concentration of 2.56 mg/ml was infused at a rate of 3.19 ml/minute by 10-ml syringes driven by Med-Associates syringe pumps.

Surgery

Before starting training on the behavioral procedures, all rats were surgically prepared with chronic indwelling jugular vein catheters, using procedures described in detail elsewhere (Thomsen & Caine, 2005; Tunstall & Kearns, 2014). All surgery was conducted under ketamine (60 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) anesthesia. Rats were given 5-10 days to recover from surgery. Catheters were flushed daily with 0.1 ml of a saline solution containing 1.25 μg/ml heparin and 0.08 mg/ml gentamicin.

Procedure

Experiment 1

Phase 1: Demand for Cocaine and Food

The demand procedure used here was similar to that in Christensen et al. (2008a). Rats were first trained to lever press for cocaine and for food on a fixed-ratio (FR) 1 schedule. During sessions lasting 3 h, there were eight components lasting 15 min each where one of the two retractable levers was inserted. There were four presentations each of the cocaine and food levers, with the order of presentation randomized with the restriction that there were no more than two consecutive components of the same type. Each component was followed by a 7.5-min period where both levers were retracted. Thus, over the course of the 3-h session, rats had access to each of the levers for a total of 60 min. The position (left vs. right) of the cocaine and food levers was counterbalanced over rats. During cocaine-lever components, a lever press resulted in infusion of a 1.0-mg/kg cocaine infusion and simultaneous illumination of the cue light above the lever and presentation of the tone for 10 s. During food-lever components, a lever press resulted in delivery of a 45-mg food pellet.

Rats were trained on this procedure with an FR-1 schedule for a minimum of eight sessions and until the consumption of each reinforcer stabilized. Stability was defined as three consecutive sessions where the total number of reinforcers earned of each type did not vary from the rolling three-session mean by more than 20%. Once this stability criterion was reached, the FR increased over blocks of two to three sessions according the following sequence: 3, 10, 32, 100, 320, 560. The progression of the sequence ended early if a rat’s consumption of both reinforcers at a particular FR declined to less than 10% of consumption observed at FR 3.

Phase 2: Choice between Cocaine and Food

Upon completion of demand testing, rats were trained on a discrete-trials choice procedure like that introduced by Cantin et al. (2010) and used by Tunstall and Kearns (2013, 2014, 2015). Each session began with four forced-choice trials. There were two forced-choice trials each with the cocaine and food levers, with trial order randomized within blocks of two. These forced-choice trials ensured that rats sampled each lever twice at the beginning of each session. On a cocaine trial, the cocaine lever was inserted into the chamber and a single lever press resulted in delivery of a 1.0-mg/kg cocaine infusion, presentation of the associated 10-s audiovisual cue, and retraction of the lever. On a food trial, the food lever was inserted and a single lever press resulted in delivery of a food pellet and retraction of the lever. Each trial was followed by a 10-min intertrial interval (ITI). Following the four forced-choice trials, there were 14 free-choice trials. Now, both levers were inserted simultaneously. A single press on the selected lever resulted in delivery of the designated reinforcer and retraction of both levers. A 10-min ITI followed each free-choice trial. Rats were trained on this procedure for at least five sessions and until preference stabilized. The stability criterion was three consecutive sessions where the number of choices a rat made for its preferred reinforcer (whether cocaine or food) did not vary by more than 20% from the rolling three-session mean.

Experiment 2

Phase 1: Demand for Cocaine and Saccharin

Rats in Exp. 2 were trained on the same demand procedures used in Exp. 1 except access to a 0.2% (w/v) saccharin solution was the non-drug reinforcer instead of a food pellet. When rats earned a saccharin reinforcer, the saccharin sipper tube was inserted into the chamber for 20 s, allowing rats to drink from it. As in Exp. 1, cocaine infusions were accompanied by a 10-s tone-light cue.

Phase 2: Choice between Cocaine and Saccharin

Rats were trained on the same choice procedure used in Exp. 1 except the non-drug alternative was 20-s access to the saccharin solution instead of food. As in Exp. 1, rats were trained on this procedure for at least five sessions and until meeting the same stability criterion used in Exp. 1. After meeting this criterion, rats were trained for an additional five sessions on a procedure where the ITI that preceded each free-choice trial was increased from 10 min to 60 min. The number of free-choice trials per session was reduced to three so that sessions did not become extremely long. There were still four forced-choice trials at the start of session separated by 10 min ITIs. After the five choice sessions with the 60-min ITI procedure, rats were trained for five additional sessions with the original 10-min ITI procedure.

Data Analysis

For all statistical tests, the significance level was set to 0.05. For collections of related multiple t-tests, the Benjamini-Hochberg (1995) procedure was used to control the false discovery rate at ≤ 0.05.

For the demand data, the number of cocaine infusions self-administered and the number of food or saccharin reinforcers earned was averaged over the training sessions at each FR (for FR 1, the mean of the last three sessions was used). These consumption data were fit by Hursh and Silberberg’s (2008) exponential demand equation:

| (1) |

where Q is quantity consumed, Q0 is consumption as price approaches 0, k is a constant defining the consumption range in log units (k = 3.5 here), α determines the rate of decline in consumption, and C is cost (FR value). Demand curves are presented in two ways. First, the number of reinforcers earned was plotted as a function of FR. Then, to facilitate comparison of demand elasticity across reinforcers when baseline consumption differed, normalized consumption was plotted as a function of normalized price (Christensen et al. 2008a). To normalize consumption, the number of cocaine infusions and food or saccharin reinforcers obtained was expressed as percentage of Q0, the consumption level predicted by the model as price approaches 0. Price was normalized by converting it to the number of responses required at a particular FR to obtain 1% of Q0. Values of α and EV are the same for model fits of the raw data or of the normalized data.

After obtaining values of α from the model fits, EV was calculated according the formula given by Hursh (2014):

| (2) |

EV was the primary measure of interest from the demand phase.

Extra sum-of squares F-tests were used to determine whether the best-fit values for group mean demand curve parameters significantly differed over reinforcers (Winger et al. 2006). The null hypothesis was that parameters did not differ and therefore a single demand curve fit the data for both reinforcers. A significant F-statistic indicated that a single demand curve could not accommodate the consumption data for both reinforcers.

For the choice data, the percentage of free-choice trials on which cocaine was chosen, averaged over the three criterion sessions, was the primary measure of preference. Rats were classified as cocaine preferrers if they chose cocaine on greater than 50% of trials and as food or saccharin preferrers if they chose cocaine on fewer than 50% of trials.

The technique used to assess for serial dependencies in choice is based on Shimp (1966). In his report, choice sequences were tallied, with each sequence reset by reinforcement. From these data it is possible to calculate the probability of a choice as function of prior reinforcers. For each subject’s set of free choices during the final three (i.e., criterion) choice sessions, instances when cocaine was chosen or when the non-drug alternative was chosen were noted. For each type of choice, the reinforcer chosen on the next trial was then also noted. This provided two conditional percentages: the percentage of trials on which cocaine was chosen given a prior choice of cocaine and the percentage of trials on which cocaine was chosen given a prior choice of the non-drug alternative. The same procedure was followed to obtain conditional percentages of cocaine choice given two consecutive cocaine choices or given two consecutive choices of the non-drug alternative. Repeated measures ANOVAs and paired-samples t-tests were used to statistically evaluate sequential dependencies. The null hypothesis in these analyses was that the percent choice of cocaine on trials when cocaine was chosen on the preceding trial(s) was not different from the percent choice of cocaine on trials when the non-drug alternative was chosen on the preceding trial(s). Rejection of the null hypothesis implies the sequential dependence of choice.

Multiple linear regression was used to determine whether the EVs of cocaine and the alternative reinforcer predicted cocaine choice. Pearson coefficients are also reported for the zero-order correlations among each of these variables. A post-hoc analysis combined the subjects from Exp.s 1 and 2 by first converting the EVs of cocaine and the alternative reinforcer, as well as percent choice of cocaine, into z-scores for each experiment separately.

For select individual subjects, whole-body cocaine levels over the course of single choice sessions were estimated based on the half-life of cocaine. A half-life of 18.1 minutes was used in the estimates because Barbieri et al. (1992) observed this elimination rate in rats self-administering 1.0 mg/kg cocaine infusions (the dose used in the present experiments). Following the method used by Weiss et al. (2003), mg/kg of cocaine in the body at time n was estimated to be:

| (3) |

where Bn-1 was the amount (mg/kg) of cocaine in the body from previous infusions, D was the dose of cocaine for the current infusion (always 1.0 mg/kg in the present study), K was 0.0383 (based on a 18.1-min half-life), and T was minutes since last infusion.

RESULTS

Experiment 1

Demand for Cocaine and Food

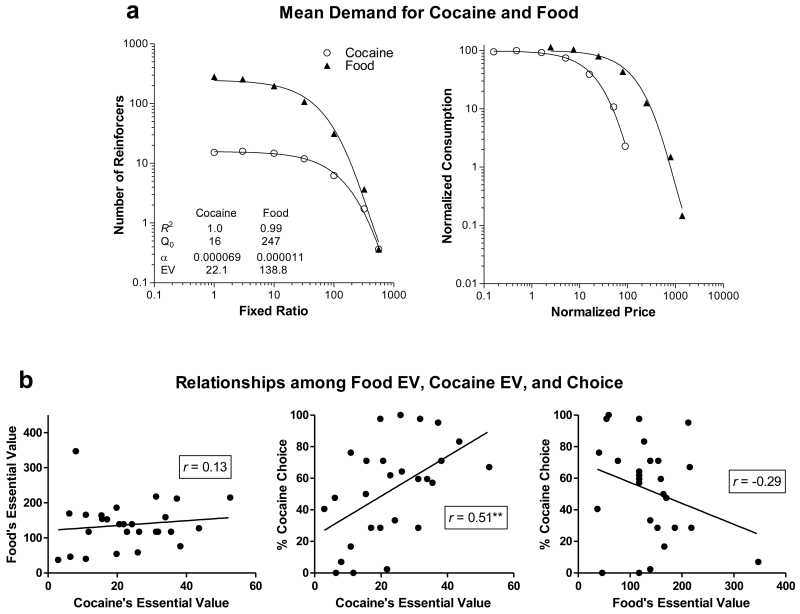

Rats required an average of 10.7 (± 0.6 SEM) sessions to meet the acquisition criterion on the FR 1 schedule. Averaged across the final three sessions on FR 1, rats self-administered a mean of 15.3 (±1.0 SEM) cocaine infusions and earned a mean of 282.1 (± 17.8 SEM) food pellets. The left panel of Figure 1a shows group mean consumption of each reinforcer across the sequence of increasing FRs as well as the exponential model fit. The right panel shows the same data expressed in normalized units. The exponential model fit the data well, with R2 values of 1.0 and 0.99 for cocaine and food, respectively.

Figure 1.

(a) Group mean demand for cocaine and food for rats in Exp. 1. The left panel presents numbers of cocaine infusions and food pellets earned at each FR plus demand curves fit by the exponential model. The right panel shows normalized consumption as a function of normalized price as well normalized demand curves fit by the model. Consumption is normalized by expressing the numbers of reinforcers earned as a percentage of Q0. Normalized price is the number of responses required at a particular FR to obtain 1% of Q0. (b) Scatterplots and best-fit lines showing relationships between cocaine’s essential value and food’s essential value (left panel), cocaine’s essential value and percent of trials on which cocaine was chosen (middle panel), and food’s essential value and percent of trials on which cocaine was chosen (right panel). ** indicates p < 0.01.

As the right panel of Figure 1a illustrates most clearly, rats worked harder to defend baseline consumption of food than baseline consumption of cocaine. The extra sum-of-squares F-test indicated that best fit parameters significantly differed over reinforcers (F[2,10] = 135.0, p < 0.001). For every subject, the EV of food was higher than that of cocaine.

Choice Between Cocaine and Food

Rats required a mean of 5.6 (± 0.2 SEM) sessions to meet the criterion on the choice procedure. On average, rats chose cocaine on 52.4% (± 5.8% SEM) of free-choice trials averaged over the three criterion sessions. Individual subjects varied widely in preference, with some choosing cocaine exclusively and others choosing food exclusively. There were 15 cocaine preferrers and 11 food preferrers. One rat chose cocaine or food on exactly 50% of trials and was therefore not classified as either a cocaine preferrer or a food preferrer.

Relationships between Demand and Choice

Figure 1b presents individual subjects’ data in the form of scatterplots showing the relationships among cocaine EV, food EV, and choice. The left panel shows that there was no association between the EV of cocaine and the EV of food (Pearson r = 0.13, p > 0.50). Thus, it was not the case that individuals that worked hard to defend consumption of one reinforcer also worked hard to defend consumption of the other reinforcer. A multiple linear regression analysis, with percent cocaine choice as the outcome and the EVs of the two reinforcers as the predictors, found a significant regression equation (F[2,24] = 7.5, p < 0.005). R2 was 0.38. Cocaine choice percentage was predicted to be 43.6 + (cocaine EV * 1.38) – (food EV * 0.17). Both cocaine EV and food EV were significant predictors of choice (cocaine, p < 0.005; food, p < 0.05). The standardized βs were 0.56 and −0.36 for cocaine and food, respectively. There was a significant positive zero-order correlation between cocaine EV and cocaine choice (Pearson r = 0.51, p < 0.01) and there was a negative but non-significant zero-order correlation between food EV and cocaine choice (Pearson r = −0.29, p = 0.15).

Sequential Dependencies in Choice

An analysis of within-session patterns of choices on the final three choice sessions revealed sequential dependencies. The reinforcer chosen on a particular trial was influenced, in part, by the reinforcer chosen on the preceding trial (or trials). For both cocaine preferrers and food preferrers, cocaine choice was more likely when the choice on the previous trial was for food than when it was for cocaine (Figure 2a). (Conversely, the likelihood of choosing food was lower when the last choice was for food than when it was for cocaine.) A 2 × 2 (subgroup × trial type) repeated measures ANOVA confirmed that there were main effects of subgroup (F[1,21] = 78.6, p < 0.001) and trial type (F[1,21] = 25.8, p < 0.001), but no subgroup × trial type interaction. (F[1,21] = 2.0, p > 0.15). (There were 14 cocaine preferrers and 9 food preferrers included in this analysis. Three rats were not included because they exclusively chose either cocaine or food and therefore sequential dependencies for both reinforcers could not be calculated.)

Figure 2.

Sequential dependencies in Exp. 1. Data shown are the mean (± SEM) percentage of free choices for cocaine when the choice on the preceding trial (a) or preceding two trials (b) was for cocaine (black bars) or food (white bars) in cocaine preferrers (n = 14 in panel a, n = 11 in panel b) and food preferrers (n = 9 in panel a, n = 5 in panel b). *** indicates the main effect of trial type was significant at p < 0.001.

While choice for the preferred reinforcer was reduced following a trial on which the preferred reinforcer was chosen, preference did not reverse. One-sample t-tests, where mean percent cocaine choice was compared to 50% (the value indicating no preference), confirmed that cocaine preferrers showed significant preference for cocaine even on trials where the preceding choice was for cocaine (t[13] = 4.4, p < 0.005) and food preferrers showed significant preference for food even on trials where the preceding choice was for food (t[8] = 2.8, p = 0.02).

Figure 2b shows the percentage of trials on which cocaine was chosen after a sequence of either two consecutive choices for cocaine or two consecutive choices for food. (Three of the cocaine preferrers and four of the food preferrers that were included in the preceding analysis were not included here because they did not have sequences of at least two consecutive choices for both reinforcers.) Now, the sequential dependency of choice is even more apparent. Cocaine preferrers’ percent choice of cocaine following two consecutive cocaine choices was only 59% as compared to 83% following two consecutive food choices. Similarly, food preferrers chose cocaine 47% of the time after two consecutive food choices, but chose cocaine only 10% of the time after two consecutive cocaine choices. A 2 × 2 (subgroup × trial type) repeated measures ANOVA confirmed that there were main effects of subgroup (F[1,14] = 29.9, p < 0.001) and trial type (F[1,14] = 24.2, p < 0.001), but no significant subgroup × trial type interaction (F[1,14] = 1.1, p > 0.3). One sample t-tests, where percent choice for cocaine was compared to 50%, indicated that cocaine preferrers maintained significant preference for cocaine even after two consecutive cocaine choices (t[10], = 13.9, p < 0.001). Food preferrers’ mean percent choice was no longer significantly different from 50% following two consecutive food choices (t[4] = 0.3, p > 0.75).

To illustrate the impact of choice sequences on estimated whole-body cocaine levels, Figure 3 shows event records from individual choice sessions from individual subjects. Two examples of food-preferring rats and two examples of cocaine-preferring rats are presented. For the food preferrer presented in the top panel (Subject 15), the mean cocaine level was 0.46 mg/kg (± 0.07 SEM) prior to cocaine choices and 0.79 mg/kg (± 0.07 SEM) prior to food choices. This rat chose cocaine on all occasions (3 of 3) when the cocaine level was below 0.5 mg/kg and chose food on 10 of 11 occasions when the cocaine level was above 0.5 mg/kg. Subject 3 shows a similar pattern, but with some more variability in cocaine levels. The third panel illustrates the behavior of a cocaine-preferring rat (Subject 2). For this subject, the mean cocaine level was 1.36 mg/kg (± 0.09 SEM) prior to cocaine choices and 2.00 mg/kg (± 0.19 SEM) prior to food choices. This rat chose cocaine on all occasions (7 of 7) when the cocaine level was below 1.5 mg/kg and chose food on 4 of 7 occasions when the cocaine level was above 1.5 mg/kg. Subject 5, another cocaine preferrer, displays a similar pattern (bottom panel).

Figure 3.

Estimated whole-body cocaine levels on a minute-to-minute basis for selected individual subjects during single choice sessions. Upticks on the x-axis indicate when a reinforcer was delivered (C = cocaine, F = food). The dotted horizontal line represents the mean estimated whole-body cocaine level maintained during the free-choice portion of the session. The first four trials of each session (left of vertical line) were forced-choice trials and the remainder (right of vertical line) were free-choice trials.

Experiment 2

Demand for Cocaine and Saccharin

Rats required a mean of 16.1 (± 1.6 SEM) sessions to meet the FR 1 lever-press acquisition criterion. On the final 3 sessions of acquisition, rats self-administered a mean of 10.4 (± 1.5 SEM) cocaine infusions and obtained a mean of 47.4 (± 4.4 SEM) saccharin reinforcers. The left panel of Figure 4a shows the mean number of reinforcers consumed at each FR and the right panel presents the same data in normalized terms. (There are only five points for cocaine because no rats in Exp. 2 obtained any cocaine infusions on FR 560.) The exponential demand model fits the data well, with R2 values of 0.99 and 0.93 for cocaine and saccharin, respectively.

Figure 4.

(a) Group mean demand for cocaine and saccharin for rats in Exp. 2. The left panel presents numbers of cocaine infusions and saccharin reinforcers earned at each FR plus demand curves fit by the exponential model. The right panel shows normalized consumption as a function of normalized price as well normalized demand curves fit by the model. (b) Scatterplots and best-fit lines showing relationships between cocaine’s essential value and saccharin’s essential value (left panel), cocaine’s essential value and percent of trials on which cocaine was chosen (middle panel), and saccharin’s essential value and percent of trials on which cocaine was chosen (right panel). ** and * indicate p < 0.01 and p < 0.05, respectively.

As illustrated most clearly by the right panel of Figure 4a, elasticity of demand for the two reinforcers was comparable. The EVs of cocaine and saccharin were 5.7 and 9.0, respectively. The extra sum-of-squares F-test indicated that a global fit could accommodate the data for both cocaine and saccharin (F < 1). For 8 rats, the EV of cocaine was higher than that of saccharin; for 12 rats, the EV of saccharin was higher than that of cocaine.

Choice between Cocaine and Saccharin

Rats required a mean of 5.5 (± 0.3 SEM) sessions to meet the stability criterion during the initial choice phase. Rats’ mean percent choice for cocaine was 54.2% (± 9.4 SEM). Individual subjects’ preference ranged from 0% to 100% choice of cocaine. There were 11 cocaine preferrers and 9 saccharin preferrers.

Relationships between Demand and Choice

Figure 4b presents scatterplots which show, for individual subjects, the EV of cocaine, the EV of saccharin, and percent choice of cocaine. There was no association between the EV of cocaine and the EV of saccharin (left panel, Figure 4b; r = −0.10, p > 0.65). Thus, as in Exp. 1, it was not the case that subjects that worked hard to defend consumption of one reinforcer also worked hard to defend consumption of the other reinforcer. A multiple linear regression analysis performed with cocaine choice as the outcome and the EVs of cocaine and saccharin as the predictors indicated that there was a significant regression equation (F[2,17] = 14.0, p < 0.001). R2 was 0.62. Cocaine choice was predicted to be 58.2 + (cocaine EV * 4.4) – (saccharin EV * 4.3). Both cocaine EV and saccharin EV were significant predictors of choice (both ps < 0.005). The standardized βs were 0.57 and −0.49 for cocaine and saccharin, respectively. There was a significant positive zero-order correlation between cocaine EV and cocaine choice (Pearson r = 0.62, p < 0.005) and a significant negative zero-order correlation between saccharin EV and cocaine choice (Pearson r = −0.55, p = 0.01).

All eight of the rats with higher cocaine EV than saccharin EV were cocaine preferrers. Only 3 of the 12 rats with higher saccharin EV than cocaine EV were cocaine preferrers. Fisher’s exact test indicated that these frequencies (8/8 vs. 3/12) significantly differed (p < 0.005). Figure 5a shows that the mean percent cocaine choice for rats with higher cocaine EV than saccharin EV was significantly higher (t[18] = 5.8, p < 0.001) than that of rats with higher saccharin EV than cocaine EV.

Figure 5.

(a) Mean (± SEM) percent choice of cocaine in subgroups of rats for which cocaine had higher essential value than saccharin (black bar) or saccharin had higher essential value than cocaine (white bar). (b) Sequential dependencies in Exp. 2. Data presented are the mean (± SEM) percentage of free choices for cocaine when the choice on the preceding trial was for cocaine (black bars) or saccharin (white bars) in cocaine preferrers and saccharin preferrers. (c) Mean (± SEM) percent choice of cocaine in cocaine preferrers (filled circles) and saccharin preferrers (open circles) during the final five sessions of the original choice phase with a 10-min inter-trial interval (ITI) separating choices, during the five sessions with a 60-min ITI, and on the five sessions when rats were returned to the 10-min ITI procedure. (d) Sequential dependencies during choice sessions with the 60-min intertrial interval in Exp. 2. Data presented are the mean (± SEM) percentage of free choices for cocaine when the choice on the preceding trial was for cocaine (black bars) or saccharin (white bars) in cocaine preferrers (n = 9) and saccharin preferrers (n = 8). *** indicates p < 0.001. * indicates the main effect of trial type was significant at p < 0.05.

Sequential Dependencies of Choice

Similar to the results of Exp. 1, percent choice of cocaine was lower when the choice on the preceding trial was for cocaine as compared to when choice on the preceding trial was for saccharin (and vice-versa; Figure 5b). A 2 × 2 (subgroup × trial type) repeated measures ANOVA confirmed that there were significant main effects of subgroup (F[1,15] = 121.2, p < 0.001) and trial type (F[1,15] = 8.2, p = 0.01), but no significant interaction. (Rats that exclusively chose one reinforcer were not included in this analysis, leaving n = 9 cocaine preferrers and n = 8 saccharin preferrers.) However, cocaine preferrers still showed strong preference for cocaine, and saccharin preferrers still showed strong preference for saccharin even on trials where the preceding choice was for their preferred reinforcer. One-sample t-tests indicated that percent choice of cocaine on trials following a choice for cocaine was still significantly greater than 50% for cocaine preferrers (t[8] = 6.6, p < 0.001) and still significantly lower than 50% for saccharin preferrers (t[7] = 4.4, p < 0.005). Sequential dependencies after two consecutive choices of the same reinforcer are not presented for Exp. 2 because there were only three rats that had choice sequences that included two consecutive choices for cocaine and two consecutive choices for saccharin.

Effect of Increasing ITI Length

Figure 5c presents, for cocaine preferrers and saccharin preferrers, the percent choice of cocaine during the final five choice sessions of the initial 10-min ITI phase, the five sessions when the ITI was lengthened to 60 min, and the five sessions when rats were returned to the 10-min ITI procedure. Preference was largely unaffected by ITI length for the majority of rats. However, two cocaine preferrers switched their overall preference to saccharin during the 60-min ITI phase before switching preference back to cocaine during the final 10-min ITI phase. A 5 × 3 × 2 (trial × phase × subgroup) repeated measures ANOVA indicated that there was a significant main effect of subgroup (F[1,16] = 124.6, p < 0.001), but no significant effects of trial or phase and no significant interactions involving these variables (all Fs ≥ 2.6, all ps > 0.05). (Two rats, one cocaine preferrer and one saccharin preferrer, were excluded from this analysis due to catheters that failed during the additional choice phases.)

As Figure 5d shows, there were no longer sequential dependencies of choice during the the 60-min ITI phase for the cocaine preferrers (n = 6) or the saccharin preferrers (n = 6; 12 rats are included in this analysis because the other subjects exclusively chose cocaine or saccharin during this phase). A 2 × 2 (subgroup × trial type) repeated measures ANOVA confirmed that there was a main effect of subgroup (F[1,10 = 21.3, p < 0.001), but the main effect of trial type and the subgroup × trial type interaction were not significant (both Fs < 1).

Combined Analysis

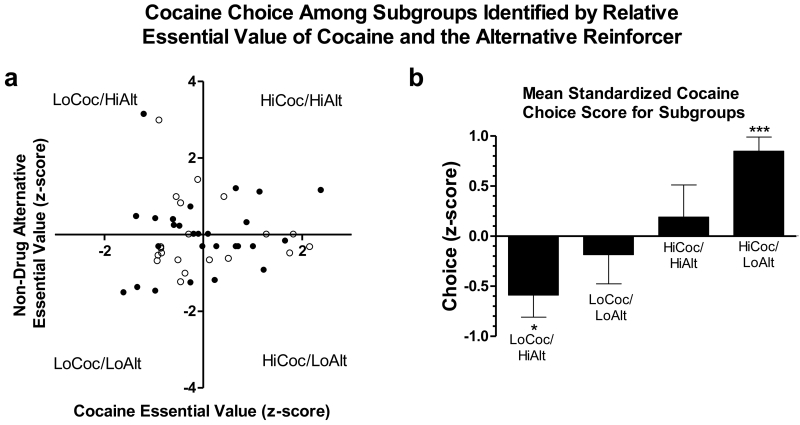

The results of the multiple regression analyses suggest that the relationship between the EV of the two reinforcers and choice was similar across experiments. The standardized βs for cocaine were 0.56 and 0.57 in Exp. 1 and 2, respectively, and those for the non-drug alternative were −0.36 and −0.49 in Exp. 1 and 2, respectively. Given this similarity, the 47 rats from both experiments were combined for an additional post-hoc analysis. Because the absolute EVs of cocaine and the non-drug alternative differed across experiments, they were first standardized by conversion to z-scores (for each experiment separately) before being combined. Percent choice of cocaine was standardized across experiments in the same way.

Figure 6a presents a scatterplot of the standardized EVs of cocaine and the non-drug alternative reinforcer for the 47 rats. Rats can be classed into four subgroups, corresponding to the four quadrants of the scatterplot, based on whether they have high (z-score > 0) or low (z-score < 0) EV of cocaine and the non-drug alternative. Figure 6b shows the standardized percent choice of cocaine for each of these four subgroups. One sample t-tests indicated that mean standardized cocaine choice score was significantly above 0 (i.e., the value corresponding to average cocaine preference) only for the subgroup of rats with high cocaine EV and low alternative EV (t[10] = 6.1, p < 0.001). For rats with low cocaine EV and high alternative EV, the mean standardized cocaine choice score was significantly below 0 (t[13] = 2.7, p < 0.02). The other two subgroups’ mean standardized cocaine choice scores did not significantly differ from 0 (both ts < 0.7, both ps > 0.5).

Figure 6.

Data from the analysis combining rats from Exp.s 1 and 2. (a) Scatterplot of individual subjects’ standardized essential values of cocaine and the non-drug alternative. Filled circles indicate rats from Exp. 1, open circles indicate rats from Exp. 2. Rats were classed into subgroups based on which quadrant of the scatterplot they were in (“HiCoc” = high cocaine essential value, “LoCoc” = low cocaine essential value, “HiAlt” = high alternative essential value, “LoAlt” = low alternative essential value). (b) Mean (± SEM) standardized cocaine choice score for these subgroups. *** and * indicate p < 0.001 and p < 0.05, respectively.

DISCUSSION

The present study found that for rats given a choice between cocaine and a non-drug alternative reinforcer, cocaine EV was a positive predictor of cocaine preference and the EV of the alternative (whether food or saccharin) was a negative predictor of cocaine preference. In Exp. 2, a simple comparison of the EVs of cocaine and saccharin for each individual could be used to predict preference with a high degree of accuracy – 85% of the rats (17 of 20) preferred whichever of the two reinforcers had the higher EV. The relationship between EV and choice was more complicated in Exp. 1. For all rats, food had substantially higher EV than cocaine, yet 15 out of 27 rats preferred cocaine over food when given a mutually exclusive choice between them.

A potential reason many rats in Exp. 1 preferred the lower EV reinforcer is that a 1.0-mg/kg cocaine infusion was a relatively larger magnitude reinforcer than a 45-mg food pellet. During FR 1 lever-press acquisition, rats self-administered 15 cocaine infusions during the one hour per session that the cocaine lever was available. In contrast, they consumed 282 food pellets per session. Thus, one cocaine infusion represented approximately 7% of baseline cocaine consumption, whereas one food pellet represented only 0.4%. This meant that during choice trials, rats were effectively choosing between a relatively large amount of a low value reinforcer vs. a small amount of a high value reinforcer. In Exp. 2, rats’ baseline consumption levels of cocaine and saccharin reinforcers were more similar (10 vs. 47). This suggests that EV is most useful as a predictor of choice when dealing with reinforcers that maintain approximately equivalent levels of baseline consumption. Nevertheless, the EVs of cocaine and food were still significant predictors of choice in Exp. 1 despite producing very different baseline consumption levels.

In the present experiments a slight majority of rats (~55%) preferred cocaine over the non-drug alternative. This contrasts with previous experiments from our lab (Tunstall & Kearns, 2013, 2014, 2015) and others (e.g., Cantin et al., 2010) that have found 15-20% cocaine preference using a similar discrete-trials choice procedure. A possible explanation for this difference in cocaine preference is that that in the present experiments rats received many training sessions with intermixed components of cocaine- and food- or saccharin-reinforced responding prior to the choice phase, whereas the previous studies used acquisition procedures where only one reinforcer was available per session, either in alternating sessions (Cantin et al., 2010; Tunstall & Kearns, 2015) or in successive phases (Tunstall & Kearns, 2013, 2014). Within-session exposure to cocaine and the non-drug-alternative reinforcer could have created a situation where rats learned a drug-induced conditioned taste aversion (CTA), the phenomenon where pairings of a food or fluid with a drug like cocaine reduce subsequent consumption of that food or fluid (Verendeev & Riley, 2012), at least early in training. While potential aversive conditioning did not prevent food or saccharin from functioning as reinforcers (rats earned a mean of 282 and 47 food and saccharin reinforcers, respectively, per session by the end of acquisition), it is possible that subtle aversive properties were conditioned to the non-drug-alternatives. This could have acted to reduce their value relative to that in the previous studies where acquisition did not involve within-session exposure to both cocaine and the non-drug alternative. The present experiments were not designed to assess CTA and therefore did not have the control conditions necessary to determine conclusively whether a CTA occurred. However, the possibility that some aversion learning occurred could explain the higher rate of cocaine preference observed in the present experiments.

Previous studies have investigated the relationship between progressive-ratio schedule breakpoint (BP) and choice between cocaine and non-drug alternatives. Cantin et al. (2010) obtained BPs for rats responding for saccharin (20 s access to a 0.2% solution; same as in Exp. 2 here) or 0.25-mg cocaine infusions (equivalent to 0.75 mg/kg/infusion for a 333-g rat) prior to allowing rats to choose between these reinforcers on a discrete-trials procedure like that used here. These investigators found that, in general, individual differences in BPs for cocaine and saccharin were not good predictors of subsequent preference, accounting for only 15% of variance in choice behavior. The majority (65.6%) of rats were behaviorally incongruent across the BP and choice measures – i.e., they preferred the reinforcer with the lower breakpoint. This contrasts with the results of Exp. 2 here, where 85% of subjects preferred the reinforcer with higher EV and individual differences in EV accounted for 62% of the variance in choice behavior. Perry et al. (2013) also investigated the relationship between BP and cocaine choice in rats. They found that while breakpoint for cocaine or food measured early in training did not predict later choice between reinforcers, a subset of rats that developed a preference for cocaine over several weeks of choice training subsequently displayed higher BPs for cocaine and lower BPs for food than rats that maintained preference for food (see Perry et al., 2015 for similar results).

The difference in results across studies using BP and EV as predictors of choice suggests that these measures capture different aspects of behavior. This is not surprising given the differences in procedures used to obtain each measure. Demand curve procedures permit the observation of continuously varying levels of consumption across multiple ratios. In contrast, on a progressive-ratio schedule, consumption at each ratio is binary – either the animal obtained a reinforcer or did not. While EV reflects sensitivity to price as measured across of range of prices and therefore indexes inelasticity of demand, BP – the last ratio completed before the animal quits responding – may better reflect resistance to extinction. Given these procedural differences, as well as the important point that EV (but not BP) is independent of scalar properties of the reinforcer, it is not surprising that in studies that have used both EV and BP, different outcomes have been found for the two measures (Lamb & Daws, 2013; Panlilio et al., 2013).

Rats in the present experiments were more likely to choose a reinforcer after having chosen the other reinforcer on previous trials. These sequential dependencies indicate that a preference measure based on whole-session data is aggregated over instances where preference fluctuates from trial to trial. The fluctuations in preference were not so extreme in the present experiments that cocaine preferrers switched preference to the non-drug alternative after having chosen cocaine. However, that there were sequential dependencies suggests that cocaine and the alternative reinforcer were interacting to some extent in determining choice. Lengthening the ITI to from 10 to 60 min in Exp. 2 appears to have minimized these interactions because the sequential dependencies were no longer apparent with the longer ITI.

Because there were no external cues signaling which reinforcer had been chosen on the previous trial, it is likely that the internal state produced by cocaine influenced choice on a trial-to-trial basis. (It seems unlikely that a single food pellet earned 10 min previously would alter internal satiety cues appreciably.) This hypothesis is consistent with the well-established observation that rats regulate their intake of cocaine (Lynch & Carroll, 2001; Tsibulsky & Norman, 1999) and that this regulation is based on the interoceptive cue produced by cocaine (Panlilio et al. 2008). In choosing cocaine more frequently on trials following choices of the alternative reinforcer, it appears that most rats were attempting to maintain some minimal level of cocaine intake, with strongly cocaine-preferring rats regulating intake around a higher minimum level than less strongly cocaine-preferring rats (see Figure 3).

The account provided above suggests that the relative values of the two reinforcers changed dynamically from trial to trial. After one or more choices of cocaine, its value decreased relative to the alternative, whereas after one or more choices of the alternative, cocaine’s value increased relative to the alternative. Vandaele et al. (2016) have recently reported another way in which the value of cocaine and a non-drug alternative can interact in a choice situation. They found that with short (1-min) ITIs, the anorexic effects of cocaine reduced the value of saccharin to such an extent that rats exclusively chose cocaine. Only when the ITI was lengthened to 10 min (as used here), allowing time for cocaine’s anorexic effects to dissipate, did saccharin have sufficient value for rats to choose it. Vandaele et al. (2016) used a cocaine dose of 0.25 mg/infusion (equivalent to approximately 0.6 mg/kg/infusion in 400-g rats) whereas a dose of 1.0 mg/kg/infusion was used in the present experiment. This raises a question of whether 10 min were sufficient to allow the anorexic effects of cocaine to dissipate. Some evidence suggesting that a 10-min ITI was sufficient comes from the sequential dependency data, which indicate that rats were more likely to choose food or saccharin having chosen cocaine on previous trial(s). If cocaine’s anorexic effects extended through the 10-min ITI, rats should have been less likely to choose food or saccharin following a choice of cocaine.

The finding in Exp. 1 that food had much higher EV than cocaine replicates the results of Christensen et al. (2008a, 2008b), despite procedural differences (e.g., use of one non-retractable lever for both reinforcers in Christensen et al. vs. a separate retractable lever for each reinforcer here). In Exp. 2 of the present study, the EVs of cocaine and saccharin did not differ. Thus, elasticity of demand for cocaine was less like that for a substance that is necessary for survival (i.e., food in hungry rats) and more like that for a sweet taste that is void of calories and unnecessary for survival (i.e., saccharin). The pattern of results from the two experiments reported here, along with the results of Christensen et al. are consistent with the notion that cocaine is low on the reinforcer value ladder for rats (Cantin et al. 2010).

In Exp. 2, where the EVs of cocaine and saccharin did not differ, the EV of cocaine was substantially lower than it was in Exp. 1. In addition to the change in the non-drug alternative from food to saccharin across Exp. 1 and Exp. 2, rats in Exp. 1 were maintained at 85% of their free-feeding weights whereas those in Exp. 2 were not food deprived. Previous studies have found that rats more than double their intake of cocaine when food-deprived as compared to when not food-deprived (Carroll, 1985; Carroll et al. 1981). Previous studies have also found that mere access to a glucose+saccharin solution during a session decreases the rate of cocaine self-administration in rats (Carroll et al., 1989). Given the finding that food in Exp. 1 had much higher EV than saccharin did in Exp. 2, it might be expected that access to food would have had a greater suppressive effect on cocaine self-administration than saccharin would. Thus, it seems more likely that the difference in cocaine EV across experiments was due to the change in food-deprivation status rather than to the change in non-drug alternative reinforcer.

To the extent that choice of cocaine over a non-drug alternative reinforcer models addiction-like behavior, the present results suggest that addiction-prone individuals are those with reduced elasticity of demand (higher EV) for cocaine and increased elasticity of demand (lower EV) for non-drug alternatives. As shown in Figure 6, only the subset of rats with both high cocaine EV and low alternative reinforcer EV had significantly elevated preference for cocaine. Increased drug availability and decreased access to non-drug alternatives are known to contribute to addiction (Ahmed, 2005; Ahmed et al. 2013; Volkow & Li, 2005). In the present experiment, all subjects had equal access to the drug and non-drug reinforcers, but only some subjects showed preference for the drug. These results suggest that, in addition to differential availability of drug vs. non-drug reinforcers, individual differences in how those reinforcers are valued are important in addiction.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by National Institute on Drug Abuse grant DA037269.

Footnotes

Disclosure/Conflict of Interests

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author Contribution

DK and AS were responsible for the study concept and design. DK, JK, and BT contributed to the acquisition of animal data. DK & AS worked on data analysis and interpretation of findings. DK drafted the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed content and approved final version for publication.

References

- Ahmed SH. Imbalance between drug and non-drug reward availability: a major risk factor for addiction. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;526:9–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.09.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed SH. Validation crisis in animal models of drug addiction: beyond non-disordered drug use toward drug addiction. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2010;35:172–84. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed SH, Lenoir M, Guillem K. Neurobiology of addiction versus drug use driven by lack of choice. Curr Opin Neurobio. 2013;23:581–87. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2013.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augier E, Vouillac C, Ahmed SH. Diazepam promotes choice of abstinence in cocaine self‐administering rats. Addiction Biol. 2012;17:378–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2011.00368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbieri EJ, Ferko AP, DiGregorio GJ, Ruch EK. The presence of cocaine and benzoylecgonine in rat cerebrospinal fluid after the intravenous administration of cocaine. Life Sci. 1992;51:1739–46. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(92)90303-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Royal Stat Soc. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Bentzley BS, Fender KM, Aston-Jones G. The behavioral economics of drug self-administration: a review and new analytical approach for within-session procedures. Psychopharmacology. 2013;226:113–25. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2899-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentzley BS, Jhou TC, Aston-Jones G. Economic demand predicts addiction-like behavior and therapeutic efficacy of oxytocin in the rat. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2014;111:11822–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1406324111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantin L, Lenoir M, Augier E, Vanhille N, Dubreucq S, Serre F, Vouillac C, Ahmed SH. Cocaine is low on the value ladder of rats: possible evidence for resilience to addiction. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e11592. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll ME. The role of food deprivation in the maintenance and reinstatement of cocaine-seeking behavior in rats. Drug Alc Depend. 1985;16:95–109. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(85)90109-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll ME, Lac ST, Nygaard SL. A concurrently available nondrug reinforcer prevents the acquisition or decreases the maintenance of cocaine-reinforced behavior. Psychopharmacology. 1989;97:23–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00443407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caprioli D, Zeric T, Thorndike EB, Venniro M. Persistent palatable food preference in rats with a history of limited and extended access to methamphetamine self‐administration. Addict Biol. 2015;20:913–26. doi: 10.1111/adb.12220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen CJ, Silberberg A, Hursh SR, Huntsberry ME, Riley AL. Essential value of cocaine and food in rats: tests of the exponential model of demand. Psychopharmacology. 2008a;198:221–29. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1120-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen CJ, Silberberg A, Hursh SR, Roma PG, Riley AL. Demand for cocaine and food over time. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008b;91:209–16. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gancarz AM1, Kausch MA, Lloyd DR, Richards JB. Between-session progressive ratio performance in rats responding for cocaine and water reinforcers. Psychopharmacology. 2012;222:215–23. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2637-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hursh SR, Silberberg A. Economic demand and essential value. Psych Rev. 2008;115:186–98. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.115.1.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hursh SR. Behavioral economics and the analysis of consumption and choice. In: McSweeney FK, Murphy ES, editors. The Wiley Blackwell Handbook of Operant and Classical Conditioning. Wiley; Hoboken, NJ: 2014. pp. 275–305. [Google Scholar]

- Huynh C, Fam J, Ahmed SH, Clemens KJ. Rats quit nicotine for a sweet reward following an extensive history of nicotine use. Addict Biol. 2015 doi: 10.1111/adb.12306. doi: 10.1111/adb.12306 [Epup ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerstetter KA, Ballis MA, Duffin-Lutgen S, Carr AE, Behrens AM, Kippin TE. Sex differences in selecting between food and cocaine reinforcement are mediated by estrogen. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:2605–14. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koffarnus MN, Woods JH. Individual differences in discount rate are associated with demand for self‐administered cocaine, but not sucrose. Addict Biol. 2013;18:8–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2011.00361.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb RJ, Daws LC. Ethanol self‐administration in serotonin transporter knockout mice: unconstrained demand and elasticity. Genes Brain Behav. 2013;12:741–47. doi: 10.1111/gbb.12068. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenoir M, Cantin L, Vanhille N, Serre F, Ahmed SH. Extended heroin access increases heroin choices over a potent nondrug alternative. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38:1209–20. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch WJ, Carroll ME. Regulation of drug intake. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001;9:131–43. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.9.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen HB, Ahmed SH. Drug versus sweet reward: greater attraction to and preference for sweet versus drug cues. Addict Biol. 2015;20:433–44. doi: 10.1111/adb.12134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academy of Sciences . Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Panlilio LV, Hogarth L, Shoaib M. Concurrent access to nicotine and sucrose in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2015;232:1451–60. doi: 10.1007/s00213-014-3787-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panlilio LV, Thorndike EB, Schindler CW. A stimulus-control account of regulated drug intake in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2008;196:441–50. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0978-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panlilio LV, Zanettini C, Barnes C, Solinas M, Goldberg SR. Prior exposure to THC increases the addictive effects of nicotine in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38:1198–208. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry AN, Westenbroek C, Jagannathan L, Becker JB. The roles of dopamine and α1-adrenergic receptors in cocaine preferences in female and male rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015 doi: 10.1038/npp.2015.116. doi:10.1038/npp.2015.116 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry AN, Westenbroek C, Becker JB. The development of a preference for cocaine over food identifies individual rats with addiction-like behaviors. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e79465. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickard JF, Body S, Zhang Z, Bradshaw CM, Szabadi E. Effect of reinforcer magnitude on performance maintained by progressive-ratio schedule. J Exp Anal Behav. 2009;91:75–87. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2009.91-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz LP, Silberberg A, Casey AH, Paukner A, Suomi SJ. Scaling reward value with demand curves versus preference tests. Animal Cog. 2016;19:631–41. doi: 10.1007/s10071-016-0967-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimp CP. Probabilistically reinforced choice behavior in pigeons. J Exp Anal Behav. 1966;9:443–455. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1966.9-443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silberberg A, Williams DR. Choice behavior on discrete trials: a demonstration of the occurrence of a response strategy. J Exp Anal Behav. 1974;21:315–22. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1974.21-315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skjoldager P, Pierre PJ, Mittleman G. Reinforcer magnitude and progressive ratio responding in the rat: Effects of increased effort, prefeeding, and extinction. Learn Motiv. 1993;24:303–343. [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen M, Barrett AC, Negus SS, Caine SB. Cocaine versus food choice procedure in rats: environmental manipulations and effects of amphetamine. J Exp Anal Behav. 2013;99:211–33. doi: 10.1002/jeab.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen M, Caine SB. Chronic intravenous drug self‐administration in rats and mice. Curr Protocol Neurosci. 2005:9–20. doi: 10.1002/0471142301.ns0920s32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsibulsky VL, Norman AB. Satiety threshold: a quantitative model of maintained cocaine self-administration. Brain Res. 1999;839:85–93. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01717-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tunstall BJ, Kearns DN. Reinstatement in a cocaine versus food choice situation: reversal of preference between drug and non‐drug rewards. Addict Biol. 2013;19:838–48. doi: 10.1111/adb.12054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tunstall BJ, Kearns DN. Cocaine can generate a stronger conditioned reinforcer than food despite being a weaker primary reinforcer. Addict Biol. 2014 doi: 10.1111/adb.12195. doi: 10.1111/adb.12195 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tunstall BJ, Kearns DN. Sign-tracking predicts increased choice of cocaine over food in rats. Behav Brain Res. 2015;281:222–28. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.12.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tunstall BJ, Riley AL, Kearns DN. Drug specificity in drug versus food choice in male rats. Exp Clin Psychopharmacology. 2014;22:364–72. doi: 10.1037/a0037019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandaele Y, Cantin L, Serre F, Vouillac-Mendoza C, Ahmed SH. Choosing under the influence: a drug-specific mechanism by which the setting controls drug choices in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;41:646–57. doi: 10.1038/npp.2015.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanhille N, Belin-Rauscent A, Mar AC, Ducret E, Belin D. High locomotor reactivity to novelty is associated with an increased propensity to choose saccharin over cocaine: new insights into the vulnerability to addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;40:577–89. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verendeev A, Riley AL. Conditioned taste aversion and drugs of abuse: history and interpretation. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2012;36:2193–205. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow N, Li TK. The neuroscience of addiction. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1429–30. doi: 10.1038/nn1105-1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weeks JR. Experimental morphine addiction: Method for automatic intravenous injections in unrestrained rats. Science. 1962;138:143–44. doi: 10.1126/science.138.3537.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss SJ, Kearns DN, Cohn SI, Schindler CW, Panlilio LV. Stimulus control of cocaine self-administraton. J Exp Anal Behav. 2003;79:111–35. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2003.79-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winger G, Galuska CM, Hursh SR, Woods JH. Relative reinforcing effects of cocaine, remifentanil, and their combination in rhesus monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;318:223–29. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.100461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]