Abstract

Introduction

The aim of this article is to discuss methods used to analyze health-related quality of life (HRQoL) data from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) for decision analytic models. The analysis presented in this paper was used to provide HRQoL data for the ivabradine health technology assessment (HTA) submission in chronic heart failure.

Methods

We have used a large, longitudinal EuroQol five-dimension questionnaire (EQ-5D) dataset from the Systolic Heart Failure Treatment with the If Inhibitor Ivabradine Trial (SHIFT) (clinicaltrials.gov: NCT02441218) to illustrate issues and methods. HRQoL weights (utility values) were estimated from a mixed regression model developed using SHIFT EQ-5D data (n = 5313 patients). The regression model was used to predict HRQoL outcomes according to treatment, patient characteristics, and key clinical outcomes for patients with a heart rate ≥75 bpm.

Results

Ivabradine was associated with an HRQoL weight gain of 0.01. HRQoL weights differed according to New York Heart Association (NYHA) class (NYHA I–IV, no hospitalization: standard care 0.82–0.46; ivabradine 0.84–0.47). A reduction in HRQoL weight was associated with hospitalizations within 30 days of an HRQoL assessment visit, with this reduction varying by NYHA class [−0.07 (NYHA I) to −0.21 (NYHA IV)].

Conclusion

The mixed model explained variation in EQ-5D data according to key clinical outcomes and patient characteristics, providing essential information for long-term predictions of patient HRQoL in the cost-effectiveness model. This model was also used to estimate the loss in HRQoL associated with hospitalizations. In SHIFT many hospitalizations did not occur close to EQ-5D visits; hence, any temporary changes in HRQoL associated with such events would not be captured fully in observed RCT evidence, but could be predicted in our cost-effectiveness analysis using the mixed model. Given the large reduction in hospitalizations associated with ivabradine this was an important feature of the analysis.

Funding: The Servier Research Group.

Keywords: Application areas, Cardiovascular, Cost-effectiveness, Economics, Heart failure, Ivabradine, Quality of life

Introduction

The reimbursement of new pharmaceutical products is increasingly dependent on the results of cost-effectiveness analyses. Economic evaluations developed for health technology assessment (HTA) bodies such as the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) typically adopt quality-adjusted survival as the relevant outcome measure [1]. Quality-adjusted survival uses health-related quality of life (HRQoL) weights (utility values) to adjust survival time to reflect the outcome of the population under assessment. HRQoL weights typically represent patients’ quality of life on a scale where 0 represents death and 1 represents full health, although negative values are also feasible [2, 3]. In the event that randomized controlled trial (RCT) data is used to inform a decision analytic model, the appropriate analysis of HRQoL data from the RCT is crucial for reliable policy decisions.

Longitudinal HRQoL data from RCTs presents challenges to analysts. The distribution of EuroQol five-dimension questionnaire (EQ-5D) HRQoL data is typically left skewed and kurtotic. In addition, there are further issues which are specific to the analysis of such data for cost-effectiveness analyses.

Firstly, in chronic conditions such as heart failure (HF), cost-effectiveness analyses consider the impact of each intervention over the modelled populations’ lifetime, but RCTs usually provide only short-term data. Long-term HRQoL outcomes consequently need to be estimated either from an external data source or predicted (extrapolated) from observed RCT evidence. Appropriate extrapolation requires that the variation in HRQoL observed between patients is adequately explained.

Secondly, in order to predict clinical outcomes over the long term, a cost-effectiveness analysis typically captures key clinical outcomes including disease progression and resource use data such as hospitalizations. The HRQoL impact of these outcomes must also, therefore, be established in order to suitably populate a decision analytic model.

Thirdly, clinical outcomes such as hospitalization or disease progression may result in fluctuations in patient HRQoL over time. Temporary changes in HRQoL that do not occur within sufficient proximity to data collection points will not be reflected in observed RCT data. This issue is exacerbated in studies which have long periods between HRQoL assessments and can result in diluted or imprecise measures of the difference between treatments.

Fourthly, longitudinal HRQoL data are collected from the same individual at repeated intervals over the study period. Measurements from the same individual are much more likely to be correlated than measurements from different individuals and this correlation must be taken into account to avoid misrepresenting estimates [1].

Fifthly, HRQoL data are often collected in a substudy and, whilst patients may be randomized to treatment, participants may not be randomized to the substudy itself (e.g., they may be selected from certain study centers or countries). If there are imbalances in patient characteristics associated with HRQoL outcomes in substudy patients this may bias (i.e., confound) estimates of the treatment effect [4].

Finally, HRQoL data are often incomplete. Patients are less likely to complete HRQoL questionnaires as their condition deteriorates and time progresses (informative censoring). In general this could result in imprecise HRQoL estimates in later trial time periods for both treatment groups, but it could equally result in differential bias between therapies [5].

The key objective of this article is to discuss methods to analyze HRQoL data from RCTs to parameterize decision analytic models using an example based on an analysis of EQ-5D data from the Systolic HF Treatment with the If Inhibitor Ivabradine Trial (SHIFT) RCT (clinicaltrials.gov: NCT02441218). The HRQoL regression equation presented in this paper was used to provide HRQoL weights (utility values) for the cost-effectiveness analysis developed for the ivabradine NICE HTA submission in chronic heart failure; the full results of the cost-effectiveness analysis and associated clinical data are reported elsewhere [4, 5].

Methods

SHIFT Trial

Heart failure is a chronic condition which can result in substantial morbidity, reduced HRQoL, and premature death [6, 7]. SHIFT was a multicenter RCT conducted in 6505 HF patients with New York Heart Association (NYHA) class II, III, or IV HF, in sinus rhythm, and with left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≤35% and baseline resting heart rate ≥70 bpm. SHIFT demonstrated that ivabradine, a heart rate lowering therapy, in combination with standard therapy, including beta-blockade, was associated with a significant reduction in cardiovascular (CV) death or hospitalization for worsening HF (hazard ratio 0.82; 95% confidence interval 0.75, 0.90, p < 0.0001) and improved patient HRQoL [8]. SHIFT was a robust, well-conducted study and provides one of the largest samples of EQ-5D HRQoL data from an RCT in HF patients.

HRQoL Data Collection in SHIFT

SHIFT EQ-5D HRQoL data were collected in a substudy at baseline, 4 months, and annually until study close providing up to five HRQoL assessments for each patient over the observed trial period (median follow-up 22 months) [9]. The EQ-5D is a generic instrument designed to capture patient-reported outcomes across five health domains (self-care, mobility, usual activities, pain/discomfort, anxiety/depression) [2]. HRQoL weights (utility values) may be derived from the EQ-5D using country-specific values for different health profiles. All patients randomized in SHIFT were included in the EQ-5D substudy (n = 5313/6505 patients) providing a validated EQ-5D instrument was available for the country of interest (i.e., an approved country-specific EQ-5D questionnaire). The SHIFT cost-effectiveness analysis was undertaken from a UK National Health Service and Personal and Social Services (PSS) perspective [1]; hence in our analysis, HRQoL weights values were based on EQ-5D index scores using UK population preference-weights [10].

Analysis of HRQoL Data

A de novo analysis of SHIFT HRQoL data was required to provide suitable parameter estimates for the SHIFT cost-effectiveness analysis. There are a number of approaches that can be used to analyze longitudinal HRQoL data for a cost-effectiveness analysis from RCTs such as SHIFT. Simple summary measures may be used to estimate the effect of treatment on HRQoL outcomes directly, e.g., based on the mean difference in HRQoL between treatments at one or more intervals over the trial period. Summary estimates from observed data, however, may not capture the full impact of clinical events that result in temporary fluctuations in HRQoL, such as hospitalizations, as some such events occur outside of data collection. Summary estimates equally do not take into account correlation between repeated observations from the same individual. Measurements from the same individual are much more likely to be correlated than measurements from different individuals and it is important to take into account such correlation when analyzing data with repeated measures to avoid misrepresenting uncertainty in estimates and drawing incorrect inferences. Furthermore, from an economic modelling perspective, simple summary measures do not provide estimates over a sufficient time horizon nor provide adequate explanation of the variation in HRQoL to populate a cost-effectiveness analysis [11].

In addition to summary measures, a variety of regression approaches can be applied to analyze longitudinal HRQoL data. These include general linear models (GLM) and generalized estimating equations (GEE).

A GLM framework attempts to explain variation in HRQoL according to known factors including, e.g., treatment allocation, patient baseline characteristics, and key clinical outcomes. Whilst this approach can be used to explain potential variation in HRQoL outcomes, it is also not designed to explicitly take into account the longitudinal structure of the data (repeated observations for individuals over time) [12].

A GEE framework (also known as marginal or population averaged model) is an extension to GLM which takes into account the correlation associated with repeated sampling from the same individual by adjusting standard errors using an imposed (predefined) correlation structure [13].

Multilevel modelling techniques, in particular mixed models (also known as variance components modelling, hierarchical modelling, or panel data modelling) can also be used to analyze longitudinal HRQoL. There are two ways of measuring effects in multilevel modelling: fixed effects and random effects. A fixed effects model assumes that the intercept for each patient is fixed. This substantially increases the number of parameters in the model and consequently a fixed effects model can be inefficient in terms of degrees of freedom; furthermore time-invariant variables will be dropped because of the correlation between regressors and unobserved individual heterogeneity. A fixed effects model is likely to be preferable if the purpose of the model is only to provide predictions on the sample of data itself [12–14].

A random effects model is designed to estimate subject-specific effects and, hence, provides distilled estimates of the specified covariates (i.e., a fixed component of the model), plus estimates of random variation according to clusters (i.e., a random component of the model). For longitudinal HRQoL data the individual patient represents the cluster in which multiple observations over time are nested. A mixed model may include fixed or random coefficients for time-varying variables. A mixed model which includes fixed coefficients is termed a random intercept model, whilst a model which includes random coefficients for any time varying variable is a random coefficient model. Mixed models provide a flexible framework compared to GLM or GEE approaches; however, these models are not as parsimonious and require a large sample size to generate reliable results [12–14].

Statistical Methods

We evaluated HRQoL outcomes based on SHIFT EQ-5D data for the SHIFT cost-effectiveness analysis. We considered estimates of the intraclass correlation (ICC) to determine whether a multilevel model would be preferable to a GLM. The ICC estimates the proportion of variance in a regression model due to clustering and is calculated as the ratio of between cluster variance and the total variance. Intraclass correlation takes values from 0 to 1; if there is little or no difference between cluster means the ICC will be close to zero (i.e., simple linear regression model may be appropriate), whilst a value of 0.5 would be considered a large ICC [15], suggesting a multilevel model would be preferred.

Patient characteristics considered for selection in the regression model were based on the clinical study protocol, a previous regression equation in HF [10], and clinical advice and included baseline sociodemographic and clinical characteristics [age, sex, NYHA class, HF duration, LVEF, smoking status, alcohol use, diabetes, race, body mass index (BMI)], baseline use of HF medications [beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, aldosterone antagonists, loop diuretics (dose/kg/day), angiotensin II receptor antagonists, cardiac glycosides, allopurinol], baseline use of other cardiac therapies (cardiac resynchronization, implantable cardiac device, conventional bradycardia-indicated pacemaker), medical history, i.e., prior CV event (myocardial infarction, stroke, coronary artery disease, atrial fibrillation, renal disease, hypertension), and biological characteristics (serum sodium, potassium, creatinine clearance, cholesterol systolic blood pressure). Two time-varying variables were used to capture key clinical outcomes: hospitalization within a 2-month interval (hospitalizations were flagged if they occurred ±30 days from EQ-5D visit date; a 60-day window) and NYHA class. Each hospitalization was assumed to be associated with a change in HRQoL weights over a 2-month period. It is assumed that patients’ HRQoL would be affected up to 30 days before an admission (i.e., due to onset of illness) and up to 30 days after an admission (i.e., recovery). We recognize that this may or may not represent the exact duration of a hospitalization’s impact on a patient’s HRQoL; acute admissions may occur suddenly and recovery may be shorter or longer than the window considered. This time interval was chosen on the basis of clinical advice and according to practical constraints (number of observations available for analysis and a time period which would be consistent with the model cycle length and viable for the cost-effectiveness analysis).

Ivabradine exhibited greater efficacy in patients with higher baseline heart rates in SHIFT [15]; hence, the European license for ivabradine was granted for a subgroup of the trial population—patients with a baseline heart rate ≥75 bpm (SHIFT n = 4154/6505 patients). In our analysis the HRQoL regression model was developed using data from the entire SHIFT substudy cohort (n = 5313 patients). The difference in outcomes for ivabradine associated with baseline heart rate, identified in previous clinical analyses [8, 15], is captured in the HRQoL regression equation using a treatment interaction term (treatment × baseline heart rate). In order to match the population reflected in the license indication, the HRQoL estimates used in the cost-effectiveness analysis and reported in this manuscript reflect estimates for patients with a baseline heart rate ≥75 bpm (predicted from our regression equation) [5].

An initial set of variables were identified using backwards stepwise elimination and cross validated using forwards stepwise selection. The regression model was fitted with and without the variable of interest, the direction and magnitude of effect of other variables was reviewed, and a likelihood ratio test undertaken to test the significance of the nested model. The variables included in the regression model were those variables that demonstrated evidence of an important association with HRQoL outcomes based on magnitude and significance of effect (p < 0.05). The correlation matrix for the initial regression model was reviewed and those variables which appeared strongly correlated were further analyzed for evidence of collinearity. All variables included in the final HRQoL regression model were reviewed by a clinical expert to ascertain whether any spurious or unexpected results had been obtained and whether the direction and magnitude of effect for included variables was consistent with clinical expectations based on a knowledge of the published literature and clinical practice. Data were analyzed using the Stata xtmixed command in Stata Statistical Software: Release 11 (College Station, Texas, United States, StataCorp LP 2009 [16]).

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Results

EQ-5D data were collected for 5313 individual patients (2648 patients ivabradine, 2665 patients placebo) for up to five assessments (median follow-up in SHIFT was 22 months). EQ-5D data were available for 5313 patients at baseline, 5164 patients at 4 months, 4809 patients at 12 months, 2555 patients at 24 months, and 33 patients at 36 months. The reason for missing questionnaires included death, withdrawal, non-attendance for a given EQ-5D visit, non-completion of the questionnaire, and censoring [9].

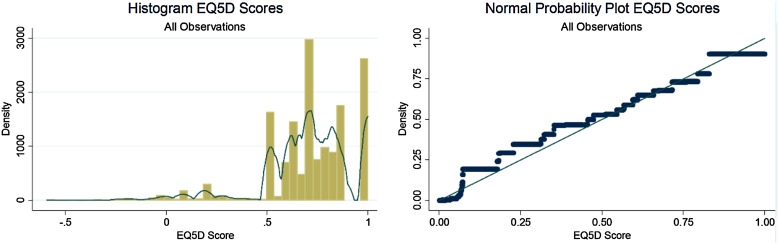

The SHIFT EQ-5D HRQoL weights data were found to be left-skewed (−1.25 versus 0 for a symmetric distribution) and kurtotic (5.67 compared to 3.00 for a normal distribution) with a mean slightly less than the median (Fig. 1). One way to analyze data with these characteristics would be to transform the data to reduce skewness and non-normality of the data; however, problems can arise when predictions from the regression model must be retransformed back to the original scale. In our analyses we did not transform HRQoL data—whilst a normal probability plot demonstrated some evidence of skewness, most data points lay over the range between 0.5 and 0.9 and the non-normality of the data was not considered extreme, see Fig. 1. Furthermore, upon investigating the model residuals, whilst HRQoL weights values were skewed, the residuals appeared approximately normally distributed.

Fig. 1.

SHIFT EQ-5D HRQoL data. EQ-5D EuroQol five-dimension questionnaire. Normal probability plot depicts expected EQ-5D values based on the standard normal distribution versus observed EQ-5D values. Histogram depicts observed frequency for each EQ-5D score (all observations) with kernel density smoother overlaid

Patient characteristics appeared well balanced between treatment groups in the EQ-5D substudy and were comparable to the baseline characteristics represented in the full SHIFT trial population, suggesting the substudy was a representative sample and there was no evidence to suggest confounding by known risk factors (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Description | Standard care n = 2665 patients |

Ivabradine n = 2648 patients |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean/freq | SE/% | Mean/freq | SE/% | |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age (years) | 60.30 | 0.22 | 60.63 | 0.22 |

| BMI (m2/kg) | 28.14 | 28.13 | ||

| Female | 599 | 22.5% | 627 | 23.7% |

| Vital signs | ||||

| Heart rate (bpm) | 79.98 | 0.19 | 79.45 | |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 121.78 | 122.25 | ||

| LVEF category | ||||

| <26% | 622 | 23.3% | 633 | 23.9% |

| ≥26%, <30% | 460 | 17.3% | 419 | 15.8% |

| ≥30%, <33% | 742 | 27.8% | 705 | 26.6% |

| ≥33% | 841 | 31.6% | 891 | 33.7% |

| NYHA class | ||||

| II | 1254 | 47.1% | 1264 | 47.7% |

| III | 1361 | 51.1% | 1346 | 50.8% |

| IV | 50 | 1.9% | 38 | 1.4% |

| Medical history | ||||

| HF duration | ||||

| <0.6 years | 628 | 23.6% | 625 | 23.6% |

| ≥0.6, <2 years | 690 | 25.9% | 676 | 25.5% |

| ≥2, <4.8 years | 665 | 25.0% | 696 | 26.3% |

| ≥4.8 years | 682 | 25.6% | 651 | 24.6% |

| Primary cause of heart failure | ||||

| Non-ischemic | 809 | 30.4% | 795 | 30.0% |

| Ischemic | 1856 | 69.6% | 1853 | 70.0% |

| MI | 1564 | 58.7% | 1538 | 58.1% |

| Hypertension | 1791 | 67.2% | 1782 | 67.3% |

| Diabetes | 820 | 30.8% | 781 | 29.5% |

| Prior stroke | 240 | 9.0% | 199 | 7.5% |

| Treatment at randomization | ||||

| Beta-blocker use | ||||

| No beta-blockade | 260 | 9.8% | 260 | 9.8% |

| <half target dose | 1060 | 39.8% | 1062 | 40.1% |

| ≥half target dose, <target dose | 715 | 26.8% | 714 | 27.0% |

| ≥target dose | 630 | 23.6% | 612 | 23.1% |

| ACE inhibitors | 2110 | 79.2% | 2121 | 80.1% |

| ARBs | 355 | 13.3% | 350 | 13.2% |

| Allopurinol | 169 | 6.3% | 162 | 6.1% |

| Loop diuretics | 2096 | 78.7% | 2109 | 79.7% |

SE standard error, BMI body mass index, bpm beats per minute, LVEF left ventricular ejection fraction, HF heart failure, MI myocardial infarction, ARBs angiotensin receptor blockers

A multilevel model was employed in preference to a GLM because there was evidence of intraclass correlation across clusters (ICC = 0.46). A log-likelihood ratio test comparing a standard linear model with linear mixed model was also statistically significant (p < 0.001), also suggesting a multilevel regression model was preferable to a GLM. A random effects model was selected in preference to a fixed effects model since the cost-effectiveness analysis was designed to provide distilled population level estimates and for a specific subgroup population (patients with a baseline heart rate ≥75 bpm) rather than the entire SHIFT sample; furthermore, a random effects model is more efficient in terms of parameter estimation [12–14]. For the final regression equation, we consequently chose to analyze SHIFT HRQoL data using a random effects (mixed model). This model was designed to predict EQ-5D HRQoL weights values according to treatment allocation, baseline patient characteristics, and key clinical outcomes. It is acknowledged that for continuous outcomes a random intercept model is comparable to a GEE (marginal model) with a uniform correlation covariance structure. Whilst, in our example, a marginal model may have been sufficient, a marginal model makes a stronger assumption with regards to missing data compared to a mixed model. A marginal model assumes that missing data is missing completely at random and there is no relationship at all between the propensity for missing data and any value in the dataset, whilst a mixed model assumes that data are missing at random.

The results of the mixed model suggest that patient’s HRQoL reduced substantially with increasing NYHA class (indicative of more severe HF) or hospitalization. Other risk factors associated with important differences in HRQoL included treatment, BMI, LVEF, HF duration, prior stroke, ischemia, and the use of other medications including loop diuretics and allopurinol, possibly indicating that patients using these medications may have been in generally poorer health. Cross tabulation of loop diuretic use and baseline NYHA class indicated that 1925/2518 (76.4%) of patients classed as NYHA I used loop diuretics compared with 81/88 (92.0%) of patients classed as NYHA IV; only 6.1% (331/5313) of all patients included in the SHIFT HRQoL substudy population used allopurinol; hence, usage patterns for this drug were more difficult to determine. Female and older patients also appeared to have lower HRQoL, consistent with previously published studies (see Tables 2, 3) [10]. Baseline heart rate was inversely associated with HRQoL weights; each 10-bpm increase in baseline heart rate was associated with an HRQoL weights loss of approximately 0.02. The estimates have not been reported in this paper; however, the HRQoL weights for patients ≥70 bpm (n = 5313 patients) were consequently only slightly higher than those reported for patients in the subgroup with a baseline heart rate ≥75 bpm (n = 3353 patients). Beta-blockade was not found to predict differences in patients’ HRQoL once these factors had been taken into account.

Table 2.

Mixed model based on SHIFT patient-level data (with treatment interaction)

| Description | Coefficient | SE | p value | 95% LCI | 95% UCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | 0.0104 | 0.0047 | 0.0270 | 0.0012 | 0.0195 |

| Age (years)a | −0.0008 | 0.0002 | 0.0000 | −0.0012 | −0.0004 |

| Female | −0.0590 | 0.0057 | 0.0000 | −0.0702 | −0.0478 |

| Hospitalization within 30 days | −0.2116 | 0.0320 | 0.0000 | −0.2744 | −0.1489 |

| NYHA II | −0.0848 | 0.0089 | 0.0000 | −0.1023 | −0.0673 |

| NYHA III | −0.1798 | 0.0094 | 0.0000 | −0.1982 | −0.1614 |

| NYHA IV | −0.3656 | 0.0182 | 0.0000 | −0.4012 | −0.3300 |

| Ischemia | −0.0365 | 0.0054 | 0.0000 | −0.0471 | −0.0258 |

| Stroke | −0.0243 | 0.0086 | 0.0050 | −0.0410 | −0.0075 |

| HF duration ≥0.6, <2 years | −0.0191 | 0.0067 | 0.0040 | −0.0322 | −0.0061 |

| HF duration ≥2, <4.8 years | −0.0394 | 0.0068 | 0.0000 | −0.0526 | −0.0262 |

| HF duration ≥4.8 years | −0.0456 | 0.0068 | 0.0000 | −0.0590 | −0.0322 |

| Allopurinol | 0.0220 | 0.0098 | 0.0260 | 0.0027 | 0.0413 |

| BMI kg/m2a | −0.0026 | 0.0005 | 0.0000 | −0.0035 | −0.0016 |

| Heart rate (bpm)a | −0.0021 | 0.0004 | 0.0000 | −0.0028 | −0.0014 |

| Loop diuretics dose/kg/day | −0.0158 | 0.0032 | 0.0000 | −0.0220 | −0.0096 |

| Potassium >5 mmol/L | −0.0142 | 0.0060 | 0.0190 | −0.0261 | −0.0023 |

| Hosp30 × NYHA I | 0.1403 | 0.0832 | 0.0920 | −0.0228 | 0.3035 |

| Hosp30 × NYHA II | 0.1792 | 0.0352 | 0.0000 | 0.1102 | 0.2482 |

| Hosp30 × NYHA III | 0.1281 | 0.0344 | 0.0000 | 0.0607 | 0.1955 |

| Treatment × heart rate | 0.0008 | 0.0005 | 0.1330 | −0.0002 | 0.0017 |

| Cons | 0.9082 | 0.0108 | 0.0000 | 0.8870 | 0.9293 |

LCI lower confidence interval, UCI upper confidence interval, NYHA New York Heart Association, HF heart failure, BMI body mass index, SE standard error

aVariables centered on the mean

Table 3.

Derived HRQoL weights values SHIFT average patient (heart rate ≥75 bpm)

| Health state | HRQoL weights |

|---|---|

| Standard care (no hospitalization) | |

| NYHA I | 0.823 |

| NYHA II | 0.738 |

| NYHA III | 0.643 |

| NYHA IV | 0.457 |

| HRQoL weights loss hospitalization | |

| NYHA I | −0.07 |

| NYHA II | −0.03 |

| NYHA III | −0.08 |

| NYHA IV | −0.21 |

| Treatment effect ivabradine | 0.014 |

NYHA New York Heart Association, bpm beats per minute

The mixed model predicted that HRQoL weights scores for patients with a heart rate ≥75 bpm ranged from 0.82 (NYHA I) to 0.46 (NYHA IV) for standard care patients and from 0.84 (NYHA I) to 0.47 (NYHA IV) for ivabradine patients; ivabradine treatment itself was associated with an HRQoL weight gain of 0.01. The reduction in HRQoL weights score given a hospitalization was found to be greater in those patients in more severe NYHA classes [reduction in HRQoL weights: 0.07–0.21 (NYHA I–IV)], see Table 3. Whilst the treatment benefit of ivabradine was not significantly modified by baseline heart rate, there was some evidence of a trend towards an effect (p = 0.13) (see Table 2). In view of previous evidence of a treatment interaction between ivabradine and baseline heart rate this interaction term was retained in the final regression model used for the NICE HTA submission (see Table 2) [4].

Discussion

We have developed a mixed model using longitudinal EQ-5D data from the SHIFT trial. Whilst there are a number of approaches that can be used to analyze HRQoL data, a mixed model offered a number of advantages. In particular, a mixed model enabled us to explain variation in EQ-5D data by treatment allocation, clinical outcomes (NYHA class and hospitalization events), and patient baseline characteristics, whilst taking into account the longitudinal data structure. The mixed model provided essential information for both short- and long-term predictions of patient HRQoL weights to populate a decision analytic cost-effectiveness model. This method also allowed us to estimate the temporary loss in HRQoL associated with hospitalizations. In SHIFT many hospitalizations did not occur close to EQ-5D data collection. Whilst temporary changes in HRQoL associated with all hospitalization events may not be captured in the RCT data, such changes in HRQoL could be predicted in our cost-effectiveness analysis using estimates from the mixed model, based on those events from which HRQoL weights could be estimated. Ivabradine was associated with a large reduction in hospitalizations in SHIFT; hence, the ability to predict the HRQoL weights loss associated with hospitalizations represented an important feature of the cost-effectiveness model.

It is noted that mixed models based on longitudinal data commonly include a set of time dummy variables to capture effects on the dependent variable that may vary over time. In our analysis a trend of increasing HRQoL was evident over the observed trial period. When we included time variables in the HRQoL regression equation, the longer-term estimates of HRQoL predicted from the HRQoL regression equation exceeded values that might be considered credible from a clinical perspective, given that heart failure is a chronic and progressive disease. In the cost-effectiveness analysis, therefore, time variables were excluded from the final HRQoL regression equation.

It is further noted that whilst the mixed model addresses many issues associated with analyzing HRQoL data, it does not account for the potential bias associated with missing data which is not missing at random. Censoring of HRQoL data may be “informative” since sicker patients are expected to be less likely to provide HRQoL responses. It is plausible that even in a well-conducted trial such as SHIFT this could distort final HRQoL weights estimates from the mixed model.

The results from our analysis appear to compare well with external data. Our results indicate that HRQoL weights for patients treated with ivabradine would range from 0.84 to 0.47, compared to 0.83–0.46 for standard care alone (NYHA class I–IV, respectively). These estimates are very similar to estimates of HRQoL from a previous large study in HF patients and appear to have good cross-validity (NYHA classes I–IV 0.85–0.53 [17]; n = 1395).

Conclusion

Summary measures of HRQoL data are typically inadequate for the needs of economic evaluations and may fail to consider limitations associated with a longitudinal dataset. These limitations, if unaddressed, may bias cost-effectiveness results, particularly given the requirements to extrapolate parameter estimates over the long term. In SHIFT a de novo mixed model was employed to address these limitations. Our analysis enabled us to explain variation in EQ-5D data according to key clinical outcomes and patient characteristics, providing essential information for predictions of patient HRQoL in the SHIFT cost-effectiveness analysis. This method also allowed us to estimate temporary losses in HRQoL associated with hospitalizations. In SHIFT many hospitalizations did not occur close to EQ-5D data collection; hence, temporary changes in HRQoL associated with such events would not be captured in observed RCT evidence, but could be predicted in our cost-effectiveness analysis using the mixed model. Given the large reduction in hospitalizations associated with ivabradine this is an important benefit for treated patients which may otherwise have been overlooked.

Acknowledgements

Sponsorship, article processing charges, and the open access charge for this study were funded by The Servier Research Group.

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval for the version to be published.

Disclosures

A. Griffiths received a salary or consultancy payment from ICON plc (Oxford Outcomes) who were contracted to undertake the study analysis. N. Paracha received a salary or consultancy payment from ICON plc (Oxford Outcomes) who were contracted to undertake the study analysis. A. Davies received a salary or consultancy payment from ICON plc (Oxford Outcomes) who were contracted to undertake the study analysis. M. Sculpher received a salary or consultancy payment from ICON plc (Oxford Outcomes) who were contracted to undertake the study analysis. N. Branscombe is a Servier employee. M. R. Cowie reports receiving consultancy and speaking fees from Servier; his salary is supported by the UK National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Unit at the Royal Brompton Hospital, London.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Footnotes

Enhanced content

To view enhanced content for this article go to http://www.medengine.com/Redeem/FE47F06046AED88D.

References

- 1.NICE. Guide to the methods of technology appraisal. London: NICE; 2013. [PubMed]

- 2.EuroQol Group. EQ-5D. http://www.euroqol.org/about-eq-5d.html. Accessed Feb 2010.

- 3.Torrance GW. HRQoL weights approach to measuring health-related quality of life. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(6):593–603. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Griffiths A, Paracha N, Davies A, Branscombe N, Cowie MR, Sculpher M. The cost effectiveness of ivabradine in the treatment of chronic heart failure from the U.K. National Health Service perspective. Heart (British Cardiac Society). 2014;100(13):1031–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.NICE. Technology Appraisal 267: ivabradine for the treatment of chronic heart failure. London: NICE; 2013.

- 6.BHF. British Heart Foundation: morbidity 2010. https://www.bhf.org.uk/research/heart-statistics. Accessed Feb 2010.

- 7.BHF. British Heart Foundation. Heart health conditions: heart failure 2013. https://www.bhf.org.uk/. Accessed Feb 2010.

- 8.Swedberg K, Komajda M, Bohm M, et al. Ivabradine and outcomes in chronic heart failure (SHIFT): a randomised placebo-controlled study. Lancet (London, England). 2010;376(9744):875–85. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Ekman I, Chassany O, Komajda M, et al. Heart rate reduction with ivabradine and health related quality of life in patients with chronic heart failure: results from the SHIFT study. Eur Heart J. 2011;32(19):2395–2404. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kind P, Hardman G, Macran S. UK population norms for EQ-5D. Discussion paper 172. York: University of York, Centre for Health Economics; 1999.

- 11.Briggs AH, Parfrey PS, Khan N, et al. Analyzing health-related quality of life in the EVOLVE trial: the joint impact of treatment and clinical events. Med Decis Making. 2016;36:965–72. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Goldstein H. Multilevel statistical models. London: Arnold; 2003.

- 13.Hubbard AE, Ahern J, Fleischer NL, et al. To GEE or not to GEE: comparing population average and mixed models for estimating the associations between neighborhood risk factors and health. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass). 2010;21(4):467–74. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Rabe-Hesketh S, Skrondal A. Multilevel and longitudinal modelling using STATA volumes 1 and 2. College Station: Stata Press; 2012.

- 15.Swedberg K, Komajda M, Bohm M, et al. Effects on outcomes of heart rate reduction by ivabradine in patients with congestive heart failure: is there an influence of beta-blocker dose?: findings from the SHIFT (Systolic Heart failure treatment with the I(f) inhibitor ivabradine Trial) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59(22):1938–1945. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.StataCorp. Stata statistical software: release 11. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2009.

- 17.Gohler A, Geisler BP, Manne JM, et al. HRQoL weights estimates for decision-analytic modeling in chronic heart failure–health states based on New York Heart Association classes and number of rehospitalizations. Value Health. 2009;12(1):185–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2008.00425.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]