Abstract

Introduction

Neovascular age-related macular degeneration (nAMD) is the leading cause of vision loss among persons aged 65 years and older. Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) treatment is the recommended standard of care. The current study compares the effectiveness of ranibizumab in routine clinical practice in two countries that generally apply two different treatment regimens, treat-and-extend (T&E) in Australia or pro re nata (PRN) in the UK.

Methods

This retrospective, comparative, non-randomised cohort study is based on patients’ data from electronic medical record (EMR) databases in Australia and the UK. Treatment regimens were defined based on location, with Australia as a proxy for analysing T&E and UK as a proxy for analysing PRN. The study included patients with a diagnosis of nAMD who started treatment with ranibizumab between January 2009 and July 2014. A total of 647 eyes of 570 patients in Australia and 3187 eyes of 2755 patients in the UK with complete 12-months follow-up were analysed.

Results

Baseline patient characteristics were comparable between the two cohorts. After 1 year of treatment, T&E-treated eyes achieved higher mean (±SE) visual acuity (VA) gains (5.00 ± 0.54 letters [95% confidence interval (CI) 3.93–6.06]) than PRN-treated eyes [3.04 ± 0.24 letters (95% CI 2.57–3.51); difference in means 2.07 ± 0.69 (95% CI 0.73–3.41), p < 0.001]. Non-inferiority of T&E compared to PRN was concluded based on the change in mean visual acuity gains at 12 months. Over the 12-month follow-up, T&E-treated eyes received a higher mean [±standard deviation (SD)] number of injections (9.29 ± 2.43) than PRN-treated eyes (6.04 ± 2.19) (p < 0.0001). Australian patients had a lower mean (±SD) number of total clinic visits (10.29 ± 2.90) than UK patients (11.47 ± 2.93) (p < 0.0001).

Conclusion

The higher injection frequency in the T&E cohort may account for the trend toward improved vision.

Funding

Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s12325-017-0483-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor, Neovascular age-related macular degeneration, Pro re nata regimen, Ranibizumab, Real-world data, Treat-and-extend regimen, Visual acuity

Introduction

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is the leading cause of blindness among persons aged 65 years and older [1] and a major cause of blindness worldwide [2]. The majority of AMD-associated vision loss is attributable to the neovascular form of the disease, known as neovascular AMD (nAMD) [3]. The introduction of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) treatment for nAMD has revolutionised its management and visual prognosis. A simulation modelling study with Australian patients suggests that intravitreal injections of ranibizumab (under T&E or PRN) can substantially lower the number of cases of blindness and visual impairment over 2 years after the diagnosis of nAMD [4, 5]. Ranibizumab is a humanised monoclonal antibody fragment that binds all forms of VEGF-A, and since its introduction in Europe and Australia, it has become the recommended standard of care in nAMD management [6–8].

In Australia, ‘treat-and-extend’ (T&E) is the universally adopted treatment regimen. In a T&E regimen, patients receive 3 monthly injections during the loading phase followed by re-treatment at intervals that may be extended in a stepwise manner [9, 10], as suggested by Spaide [11], without the need for additional monitoring visits. In the UK, guidelines for ranibizumab treatment in nAMD originally required a loading phase of 3 monthly injections, followed by an ‘as needed’ treatment (pro re nata; PRN) based on disease activity at monthly assessments [8, 12]. In 2014, the SmPC for ranibizumab allowed for T&E dosing and this is now becoming more frequent in UK.

Identifying the optimum treatment regimen for nAMD remains an ongoing challenge. The ultimate goal is to reduce the number of anti-VEGF injections required without sacrificing visual acuity (VA) gains. A recent systematic review comparing T&E and PRN anti-VEGF treatment regimens found that, on average, T&E results in greater VA gains but also requires more injections [13]. Similarly, Hatz et al. reported that ranibizumab when administered using a T&E regimen in treatment-naïve nAMD patients resulted in better visual outcomes than with a PRN regimen [14].

The purpose of the current study is to compare the effectiveness of ranibizumab administered under two different treatment regimens [T&E (Australia) or PRN (UK)] in routine clinical practice.

Methods

This was a retrospective, comparative, non-randomised cohort study. It examined the effectiveness of two different ranibizumab treatment posologies in eyes with nAMD. This study was conducted using pseudo-anonymised, highly structured, longitudinal (across visits and time) data collected within the same type of electronic medical records (EMR) database (Medisoft Ophthalmology, Medisoft, Leeds, UK) at each of the four community Medical Retina Clinics across Australia and five community Medical Retina clinics across the UK. Data collected included: demographics, VA at baseline and at each study visit, injection frequency and number of monitoring visits.

The study included patients with a diagnosis of nAMD, who had no anti-VEGF treatment 6 months before the index date and who were treated exclusively with ranibizumab between January 2009 and July 2014. The index date is defined as the first prescription of ranibizumab captured in the EMR database during the study period. The end date was chosen in order to exclude eyes from UK sites where the posology potentially changed to T&E after the label change in 2014 [9, 15]. Since then, monthly monitoring of nAMD patients receiving ranibizumab was no longer mandatory, allowing for a more flexible treatment regimen in eyes with stable disease activity.

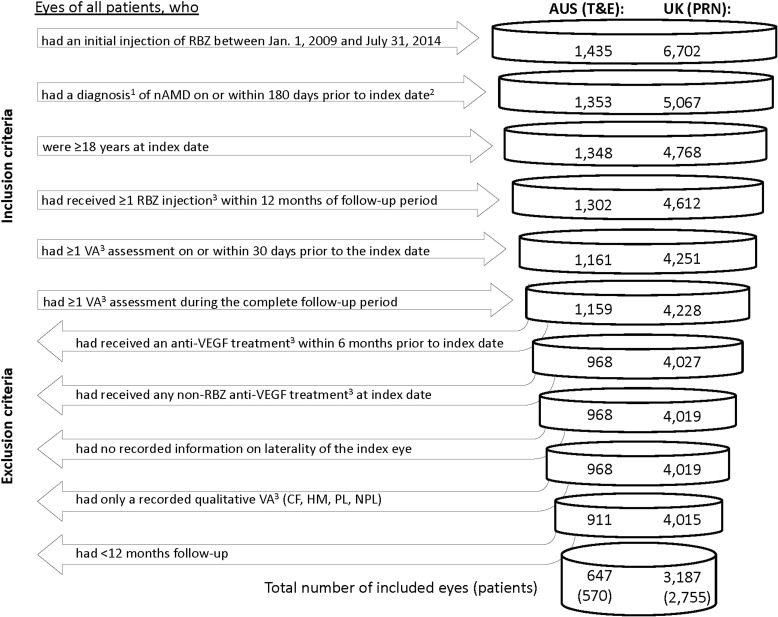

After application of the inclusion and exclusion criteria for this study (Fig. 1), EMR data included 911 eyes of 788 patients in Australia and 4015 eyes of 3458 patients in the UK. For 647 eyes of 570 patients in Australia and 3187 eyes of 2755 patients in the UK complete 12-month follow-ups were available for analysis.

Fig. 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for this study. 1The diagnosis had to be for the eye(s) where the index injection had occurred. If both eyes were injected and diagnosed, both were included. 2Date of first RBZ injection; 3in/for the study eye(s). anti-VEGF anti-vascular endothelial growth factor, AUS Australia, CF counting fingers, HM hand motion, nAMD neovascular age-related macular degeneration, NPL no perception of light, PL perception of light, PRN pro re nata, RBZ ranibizumab, T&E treat-and-extend, VA visual acuity

The primary effectiveness outcome measure was the mean change in VA from baseline to month 12. VA values were measured with a mixture of logMAR (logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution), ETDRS (early treatment diabetic retinopathy study) letter scores and Snellen measures. For the purposes of analysis all values were converted to ETDRS letter score values. VA was mainly measured with habitual correction rather than refracted best-corrected VA. If more than one measure was recorded for an eye on the same day, the best VA value was used for analysis.

Eyes were included if they had been followed for 12 months; however, because this is a study conducted in a real-world setting, eyes might not have been assessed exactly at month 12 (day 360). To address this limitation, ‘month 12’ VA measurements were defined as any measurement performed between month 9 and month 15 (270–450 days). If more than one measurement was available, the value closest to month 12 was used. If two values had the same distance, the first one was taken. A similar approach was used to define VA values for month 3 (60–120 days) and month 6 (150–210 days).

For the power calculations conducted prior to study initiation, literature-reported BCVA changes were considered: Tufail et al. reported a 12-month mean change of BCVA of two letters [12]. Gillies et al. reported a 12-month mean change of BCVA of 4.9 letters in an Australian cohort [16]. Based on this, for the study presented here, the sample size for the VA outcome analysis for non-inferiority of AUS vs. UK was calculated, assuming no difference between the two groups, a non-inferiority limit of five letters (equal to one line) and a significance level of 0.05. For simplicity, a common SD of 15.6 was assumed. As a result a minimum of 167 eyes per group were needed to achieve at least 90% power for the VA change at month 12, i.e. with 647 eyes of 570 patients in the AUS group the sample size was sufficient to assess the main study objective. Results were presented descriptively for all outcome parameters. In terms of comparative analyses, categorical outcomes were compared via a chi-square test, while for continuous variables and for differences in the mean number of visits between the two groups a two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test was used. To test for non-inferiority of T&E vs. PRN with respect to the difference in VA change at month 12, a general estimating equation (GEE) model was used. The GEE model included the covariates baseline VA and age at baseline and accounted for possible inter-eye correlation, i.e. the fact that both eyes of a patient could contribute to the study (bilateral treatment).

Ethical Approval

This study was designed, implemented and reported in accordance with the guidelines for good pharmacoepidemiology practices (GPP) of the International Society for Pharmacoepidemiology [17], the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines [18] and the ethical principles laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki. For this type of study (with all patient identifiers removed and pseudo-anonymised clinician data) formal patient informed consent is not required.

Results

Baseline patient characteristics were comparable between the Australian and the UK cohorts, and are presented in Table 1. After 1 year of treatment, the mean [±standard error (SE)] change in VA from baseline in the T&E-treated Australian cohort was 5.00 ± 0.54 letters (95% CI 3.93–6.06), while mean (±SE) change in VA from baseline in the PRN-treated UK cohort was 3.04 ± 0.24 letters (95% CI 2.57–3.51) (Table 2). The difference of mean change between the Australian and the UK cohorts was 2.07 ± 0.68 letters [(95% CI 0.73–3.41), p < 0.001]. Non-inferiority of T&E compared to PRN was concluded, since the upper boundary of the two-sided 95% confidence interval (i.e. 3.41 letters) did not exceed the non-inferiority margin of +5 letters. A comparison of the study groups based on the analysis of covariance adjusting for patient baseline VA yielded similar results (results not shown).

Table 1.

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics among patients receiving ranibizumab for nAMD treatment in the health care settings of Australia and UK

| AUS cohort | UK cohort | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | N = 570 | N = 2755 | |

| Eyes | N = 647 | N = 3187 | |

| Mean [SD] age in years | 78.49 [6.76] | 77.96 [8.14] | 0.6573 |

| Proportion of patients per age group at index date in % | 0.0027 | ||

| <65 years | 3.40 | 6.46 | |

| 65–69 years | 9.58 | 6.78 | |

| 70–74 years | 12.67 | 12.52 | |

| 75–79 years | 19.17 | 21.65 | |

| 80–84 years | 36.01 | 32.44 | |

| ≥85 years | 19.17 | 20.14 | |

| Gender (patient) in % | 0.0312 | ||

| Female | 57.82 | 63.67 | |

| Male | 42.18 | 36.33 | |

| VA study eye (eye) | 0.1979 | ||

| N | 647 | 3187 | |

| Mean [SD], letters | 54.89 [18.82] | 55.05 [15.59] | |

| VA fellow eye (eye) | <0.0001 | ||

| N | 273 | 2883 | |

| Mean [SD], letters | 65.19 [18.56] | 59.65 [23.86] | |

| VA functional groups (eye) | |||

| >70 letters | 21.48 | 17.29 | |

| 56–70 letters | 31.84 | 33.51 | |

| 35–55 letters | 34.47 | 37.68 | |

| <35 letters | 12.21 | 11.52 | |

AUS Australia, N number of eyes, SD standard deviation, VA visual acuity

Table 2.

Mean change from baseline in VA—12-month follow-up cohort

| AUS cohort | UK cohort | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VA at baseline | ||||

| LS mean estimate | 55.49 | 55.11 | ||

| SE | 0.65 | 0.29 | ||

| 95% CI | 54.22 | 65.77 | 54.55 | 55.67 |

| VA at month 12 | ||||

| LS mean estimate | 60.41 | 58.17 | ||

| SE | 0.73 | 0.32 | ||

| 95% CI | 58.98 | 61.84 | 57.54 | 58.80 |

| Mean changes at month 12 | ||||

| LS mean estimate | 5.00 | 3.04 | ||

| SE | 0.54 | 0.24 | ||

| 95% CI | 3.93 | 6.06 | 2.57 | 3.51 |

| GEEa | ||||

| Patients | N = 553 | N = 2727 | ||

| Difference of mean change AUS vs. UK at month 12 | ||||

| LS mean estimate | 2.07 | |||

| SE | 0.68 | |||

| 95% CI | 0.73 | 3.41 | ||

Non-inferiority of T&E vs. UK was concluded since the upper boundary of the confidence interval (i.e. 3.41) is smaller than the non-inferiority margin of +5 letters

AUS Australia, CI confidence interval, GEE general estimating equations, LS least square, N number of eyes, SE standard error, VA visual acuity

aThe GEE model included the covariates baseline VA and age at baseline. A comparison of the study groups based on the analysis of covariance adjusting for patient baseline VA yielded similar results (results not shown)

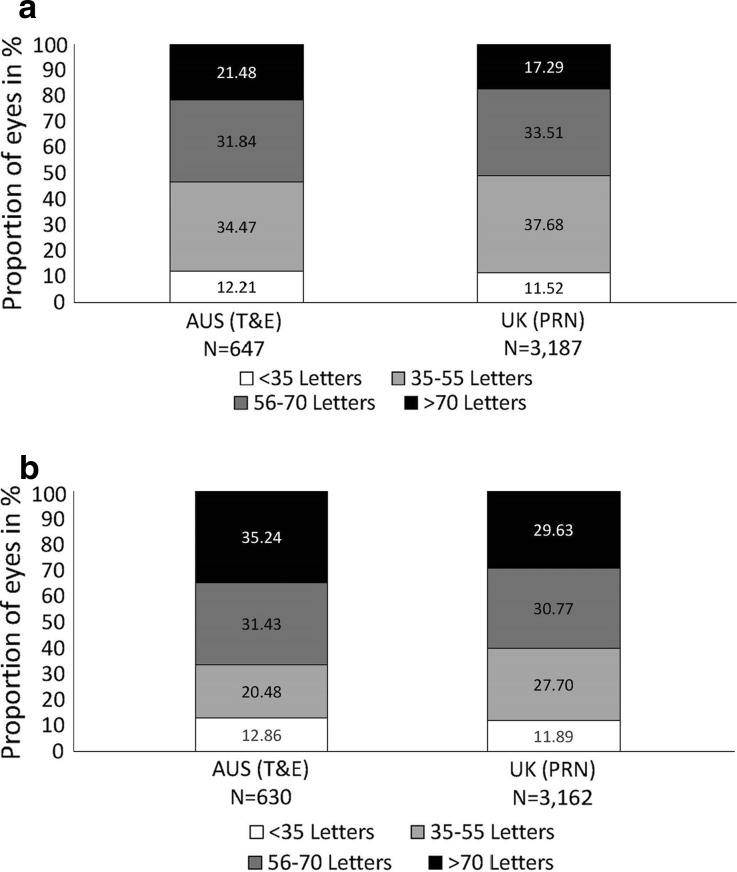

The proportion of eyes with a VA of <35 letters was similar at baseline and after 12 months under both the T&E regimen (12.86% vs. 12.21% at baseline; Fig. 2) and the PRN regimen (11.89% vs. 11.52% at baseline). Improved vision under both regimens was concluded for two reasons: (1) The proportion of eyes with VA of 35–55 letters at month 12 had decreased under both regimens (T&E 20.48% vs. 34.47% at baseline; PRN 27.70% vs. 37.68% at baseline). (2) The proportion of eyes achieving >70 letters at month 12 had increased compared to baseline (T&E 35.24% vs. 21.48% at baseline; PRN 29.63% vs. 17.29% at baseline).

Fig. 2.

Proportion of eyes (in %) per pre-defined VA category. a At baseline; b at 12 months. For each VA category the proportion of eyes was compared between T&E and PRN at 12 months, using a logistic regression model. After adjustment of the odds ratio for baseline VA, the decrease in the proportion of eyes achieving 35–55 letters in Australia (i.e. T&E) was significantly larger when compared to the UK (i.e. PRN) (p < 0.001). For the remainder categories this test did not reach statistical significance. AUS Australia, PRN pro re nata, T&E treat-and-extend, VA visual acuity

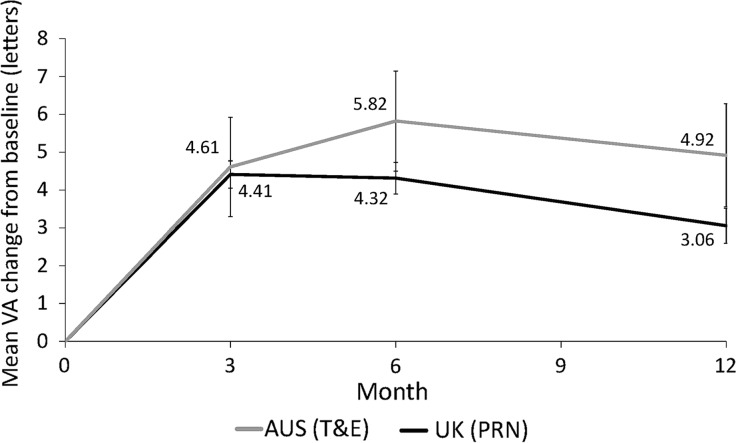

Within the loading phase, i.e. the first 3 months of monthly initial loading injections, the mean VA increased quickly under both T&E and PRN (Fig. 3). Subsequently, a positive trend remained for T&E at month 6, whereas the mean VA for PRN-treated eyes gradually declined from month 3 to 12. At month 12, eyes under a T&E regimen maintained higher mean VA gains compared to PRN.

Fig. 3.

Mean VA change from baseline by time and country—12-month follow-up cohort. Non-inferiority of T&E compared to PRN was concluded [T&E vs. PRN: 2.07 ± 0.68 (95% CI 0.73–3.41), GEE model] based on mean change in VA (±SE) from baseline to month 12. A comparison of the study groups based on the analysis of covariance adjusting for patient baseline VA yielded similar results (results not shown). AUS Australia, error bars 95% CI values, PRN pro re nata, T&E treat-and-extend, VA visual acuity

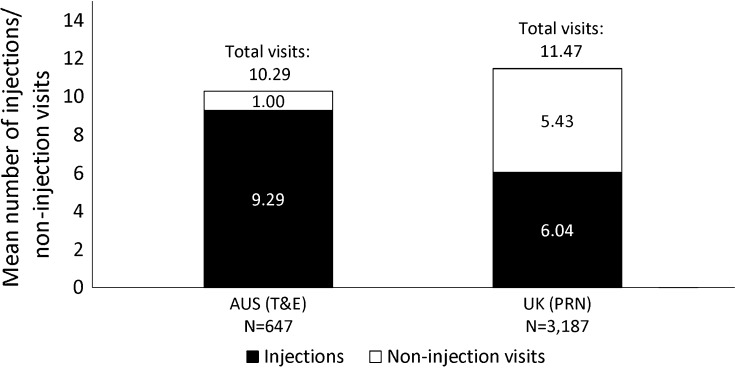

There was no difference in the mean number of injections received during the loading phase, with eyes treated under the T&E regimen receiving a mean (±SD) of 2.25 ± 0.67 injections and eyes treated under the PRN regimen receiving a mean (±SD) of 2.30 ± 0.60 injections (p < 0.0827; Supplementary Figure S1). However, over the 12-month follow-up, eyes treated under T&E received a higher mean (±SD) number of injections (9.29 ± 2.43) vs. PRN-treated eyes (6.04 ± 2.19, p < 0.0001).

The mean (±SD) total number of clinic visits was lower under a T&E regimen than under a PRN regimen (T&E 10.29 ± 2.90; PRN 11.47 ± 2.93, p < 0.0001; Fig. 4). Of note, in both Australia and the UK, some clinics run a two-stop service, i.e. the clinical assessment and treatment administration occur on different days. The primary analysis counted all visits separately. In an additional analysis, multiple visits occurring within 2 weeks of an injection were considered as one single injection visit. After adjusting for these two-stop visits the inter-country difference regarding the total number of visits remained statistically significant (p < 0.0001; Supplementary Figures S2, S3). The UK cohort also had a larger number of non-injection visits (p < 0.0001; Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Mean number of injection visits vs. non-injection visits. During their first year of treatment, T&E-treated eyes/patients had a significantly lower mean (±SD) number of non-injections visits (i.e. monitoring visits for visual acuity, optical coherence tomography or intraocular pressure; p < 0.0001) and received a significantly higher mean (±SD) number of injections than PRN-treated eyes (p < 0.0001). Differences in the mean number of visits between Australia vs. the UK were compared using a two-sided Wilcoxon rank sum test based on normal approximation. AUS Australia, N number of eyes, PRN pro re nata, T&E treat-and-extend

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the largest, real-world, comparative analysis of T&E and PRN treatment regimens with ranibizumab in nAMD. The T&E regimen resulted in a better visual outcome at 12 months compared to PRN. As this difference was less than +5 letters/one line on the ETDRS chart, the T&E regimen was concluded to be non-inferior to PRN. Unsurprisingly, the T&E regimen resulted in substantially fewer monitoring visits; however, patients treated under this regimen did receive more injections.

Several studies have reported that T&E is superior to PRN in terms of visual outcomes achieved [13, 14, 19]. Furthermore, in the retrospective consecutive comparative case series study by Hatz and Prünte [14], the T&E regimen resulted in a statistically significant greater mean change in VA from baseline with fewer clinic visits compared to a PRN regimen. In another case series of treatment-naïve patients, Hatz and Prünte [20] found a positive mean VA trend after switching regimens from PRN to T&E. Patients with active disease regained previous losses in VA experienced during the PRN maintenance phase, and a statistically significant mean VA increase was observed at 6 and 12 months. While the primary outcome of this study demonstrated non-inferiority of T&E compared to PRN, it is noteworthy that the mean change in VA from baseline under the T&E regimen compared to a PRN regimen was also statistically significant. Patients treated under T&E gained two additional letters compared to those treated under a PRN regimen.

Despite our conclusion of non-inferiority between posologies in terms of vision, the significant variation in injection frequency and clinic visits between Australia and the UK warrants discussion. Unsurprisingly, we report that during the 12-month follow-up, eyes treated under a T&E regimen received a higher mean number of injections than those under a PRN regimen (9.29 injections for T&E vs. 6.04 injections for PRN). The total number of visits also differed between the two posologies: in comparison to T&E, the PRN-treated patients had a higher mean number of total visits (±SD) during the first year of treatment (T&E 10.29 ± 2.90 vs. PRN 11.47 ± 2.93, p < 0.0001), particularly monitoring visits.

The higher injection frequency in the T&E cohort may account for both the trend toward improved vision and the reduction in the number of patients with very poor vision, in this group. Such a finding will be of particular interest to health care professionals/clinics in selecting a treatment posology for their patients and to those considering switching patients from one posology to another. Aside from visual outcomes, the treatment burden associated with intravitreal therapy in nAMD is an ongoing challenge for care givers, especially since it is suggested to contribute to poor long-term outcomes [21]. Any posology that can reduce the number of treatment and monitoring visits while maintaining vision (vs. comparator treatment posology) may help addressing this current unmet need in nAMD management.

The current findings also provide useful insights into effects of treatment posology on visual outcomes in clinical trials vs. real-world clinical practice. A recent large study using EMR data showed that in the UK (where the PRN regimen was generally used before the ranibizumab label changed), VA gains in a large, real-world population did not match those expected based on results seen in RCTs [12]. Among the reasons suggested for this was under-treatment and failure to achieve monthly follow-up. Our study suggests that moderate real-world outcomes cannot be entirely attributed to the posology used. The non-inferiority of T&E to PRN in the current study may indicate that the discrepancy between outcomes in clinical trials vs. clinical practice are more likely to be influenced by real-world population differences compared to the highly controlled populations included in RCTs. A recent study comparing outcomes from a phase III population (MARINA) with those of an observational cohort [Fight Retinal Blindness! (FRB-ALL)] and a matched observational cohort (FRB-MARINA) supports this view [16]. Despite comparable outcomes between all cohorts, the mean improvement was less for the FRB cohorts than for the MARINA clinical trial cohort. Interestingly, the mean VA gains in the EMR database study presented here are quite similar to those of the total FRB cohort (FRB-ALL).

Some limitations need to be considered for this study. First, treatment regimens were defined solely based on location, i.e. the study was analysed under the assumption that all patients in Australia and the UK were managed under T&E and PRN regimens, respectively. Consequently, some patients may have been assessed under the wrong treatment regimen. However, based on the number of injections and visits observed in this study in the two countries, the assumption concerning the predominant treatment regimens in each of the two countries was generally confirmed. Second, the Australian cohort was only one-fourth of the size of the UK cohort. Nevertheless the number of sites (four in Australia, five in UK) was similar and there was no mono-centre bias. Overall, the number of patients was large enough to measure all outcomes of interest in both cohorts. Third, only sites using the Medisoft EMR system participated, which could result in a selection bias. There is evidence in the literature for modest differences in VA outcomes between centres in the UK [22]. The authors associated this inter-centre variation with differences in patient age, starting VA, number of injections and visits. However, in the study presented here, these factors were comparable. Using the same EMR system allowed consistent data collection, which is advantageous for study conduct and data analysis. For VA measurements different vision tests were used; in both cohorts VA was mostly measured in letter score (80% vs. 91%). Fourth, as patients with insufficient follow-up time were excluded, a selection for patients with better outcomes could be expected, although this would affect both cohorts. A final limitation may be that the study did not take into account differences in genetic background as potentially influencing factors.

A key strength of this study relates to the use of EMR data, i.e. a collection of highly structured data at each visit. Independent of the regimen applied, EMR are very representative of real-life clinical care. Outcome data are collected as well, which are not available in some other data sources. The data shown here generally confirm the predominant treatment regimens in the two countries during the study period. With both treatment regimens VA improvements were observed, supporting results from clinical trials [13, 19].

Conclusion

In conclusion, both regimens of ranibizumab, T&E and PRN, led to VA improvements and represent effective treatment strategies for nAMD. No difference in the number of injections received during the loading phase was observed between the two groups. However, the T&E regimen resulted in a better outcome as evidenced in the difference of the mean changes in visual acuity from baseline to month 12 (primary outcome measure), which may be accounted for by the higher mean number of injections administered under this regimen. These results may be useful for health care professionals in determining a suitable treatment regimen for patients that considers vision improvement and the burden associated with intravitreal therapy.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to specifically acknowledge Robert Johnston. He provided profound scientific advice. He also contributed comprehensively and enthusiastically to all structural, writing and reviewing parts of the manuscript before he sadly passed away on 5 September 2016. Funding for this study was provided by Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland. The article processing charges and open access fee for this publication were funded by Novartis Pharma AG. Medical writing support was provided by Dorothea von Bredow and Jasmin Gossmann of QuintilesIMS and was funded by Novartis Pharma AG. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole and have given final approval to the version to be published.

Conceived and designed the experiments: H-JC, AS, AF, FM.

Performed the experiments: H-JC, AS, AF, FM.

Contributed analysis tools: RJ, H-JC AS, AF, FM, PM.

Analysed the data: RJ, H-JC, AS, AF, FM, PM.

Wrote or reviewed the paper: RJ, H-JC, AS, AF, FM, PM.

Disclosures

Paul Mitchell is a Consultant to Novartis and Bayer. Hans-Joachim Carius is an employee of QuintilesIMS, which has received funding from Novartis Pharma AG; Adrian Skelly is an employee of Novartis Pharma AG. Alberto Ferreira is an employee of Novartis Pharma AG. Fran Milnes is an employee of Novartis Pharma AG.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This study was designed, implemented and reported in accordance with the Guidelines for Good Pharmacoepidemiology Practices (GPP) of the International Society for Pharmacoepidemiology [17], the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines [18] and the ethical principles laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki. For this type of study (with all patient identifiers removed and pseudo-anonymised clinician data) formal patient informed consent is not required.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Footnotes

Enhanced content

To view enhanced content for this article go to http://www.medengine.com/Redeem/D587F06056571C3C.

R. Johnston sadly passed away on 5 September 2016.

References

- 1.Friedman DS, O’Colmain BJ, Munoz B, et al. Prevalence of age-related macular degeneration in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol (Chicago, Ill.: 1960) 2004;122:564–572. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Mario SP. Global data on visual impairments 2010. http://www.who.int/blindness/GLOBALDATAFINALforweb.pdf. Accessed May 9, 2016.

- 3.Wong TY, Wong T, Chakravarthy U, et al. The natural history and prognosis of neovascular age-related macular degeneration: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:116–126. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mitchell P, Bressler N, Doan QV, et al. Estimated cases of blindness and visual impairment from neovascular age-related macular degeneration avoided in australia by ranibizumab treatment. PLoS One. 2014;9:e101072. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnston RL, Lee AY, Buckle M, et al. UK Age-Related Macular Degeneration Electronic Medical Record System (AMD EMR) Users Group. Report IV: incidence of blindness and sight impairment in ranibizumab-treated patients. Ophthalmology. 2016;123:2386–2392. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.European Medicines Agency. Lucentis ranibizumab. EPAR summary for the public. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Summary_for_the_public/human/000715/WC500043548.pdf. Updated October 30, 2014. Accessed May 9, 2016.

- 7.Therapeutic Goods Administration. Australian Public Assessment Report for Ranibizumab. https://www.tga.gov.au/sites/default/files/auspar-lucentis.pdf. Accessed May 9, 2016.

- 8.NICE technology appraisal guidance [TA155]. Ranibizumab and pegaptanib for the treatment of age-related macular degeneration. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta155/resources/ranibizumab-and-pegaptanib-for-the-treatment-of-agerelated-macular-degeneration-82598316423109. Updated May 2012. Accessed May 9, 2016.

- 9.European Medicines Agency. Lucentis: EPAR-Product Information. Annex I—summary of product characteristics. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/000715/WC500043546.pdf. Updated May 11, 2016. Accessed Sept 27, 2016.

- 10.Novartis Pharmaceuticals Australia Pty Limited. LUCENTIS ranibizumab (rbe). Product information for inclusion in the Australian Register of therapeutic goods (The ARTG). https://www.ebs.tga.gov.au/ebs/picmi/picmirepository.nsf/pdf?OpenAgent&id=CP-2009-PI-00271-3&d=2016050916114622483. Updated March 24, 2016. Accessed May 9, 2016.

- 11.Spaide R. Ranibizumab according to need: a treatment for age-related macular degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143:679–680. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tufail A, Xing W, Johnston R, Akerele T, McKibbin M, Downey L, Natha S, Chakravarthy U, Bailey C, Khan R, Antcliff R, Armstrong S, Varma A, Kumar V, Tsaloumas M, Mandal K, Bunce C. Writing Committee for the UK Age-Related Macular Degeneration EMR Users Group. Report 1: visual acuity. The neovascular age-related macular degeneration database: multicenter study of 92,976 ranibizumab injections. Ophthalmology. 2014;121:1092–1101. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chin-Yee D, Eck T, Fowler S, Hardi A, Apte RS. A systematic review of as needed versus treat and extend ranibizumab or bevacizumab treatment regimens for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Br J Ophthalmol. 2016;100:914–917. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2015-306987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hatz K, Prünte C. Treat and extend versus pro re nata regimens of ranibizumab in neovascular age-related macular degeneration: a comparative 12 month study. Acta Ophthalmologica. 2017;95(1):e67–e72. doi: 10.1111/aos.13031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Novartis. Novartis announce licence change for leading sight loss treatment Lucentis (ranibizumab). http://newsroom.novartis.co.uk/UK/novartis-announce-licence-change-for-leading-sight-loss-treatment-lucentis-ranibizumab/s/b60c8753-51a4-4d9d-8aed-7c0c5bbfd972. Accessed May 9, 2016.

- 16.Gillies MC, Walton RJ, Arnold JJ, et al. Comparison of outcomes from a phase 3 study of age-related macular degeneration with a matched, observational cohort. Ophthalmology. 2014;121:676–681. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.International Society for Pharmacoepidemiology (ISPE) Guidelines for good pharmacoepidemiology practices (GPP) Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2008;17:200–208. doi: 10.1002/pds.1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Int J Surg (London, England). 2014;12:1500–1524. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Freund KB, Korobelnik J, Devenyi R, et al. treat-and-extend regimens with anti-VEGF agents in retinal diseases: a literature review and consensus recommendations. Retina (Philadelphia, Pa.). 2015;35:1489–1506. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Hatz K, Prünte C. Changing from a pro re nata treatment regimen to a treat and extend regimen with ranibizumab in neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Br J Ophthalmol. 2016;100:1341–1345. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2015-307299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boulanger-Scemama E, Querques G, About F, et al. Ranibizumab for exudative age-related macular degeneration: a five year study of adherence to follow-up in a real-life setting. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2015;38:620–627. doi: 10.1016/j.jfo.2014.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liew G, Lee AY, Zarranz-Ventura J, et al. The UK Neovascular AMD Database Report 3: inter-centre variation in visual acuity outcomes and establishing real-world measures of care. Eye (London, England). 2016;30:1462–1468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.