ABSTRACT

Thiamine biosynthesis is commonly regulated by a riboswitch mechanism; however, the enzymatic steps and regulation of this pathway in archaea are poorly understood. Haloferax volcanii, one of the representative archaea, uses a eukaryote-like Thi4 (thiamine thiazole synthase) for the production of the thiazole ring and condenses this ring with a pyrimidine moiety synthesized by an apparent bacterium-like ThiC (2-methyl-4-amino-5-hydroxymethylpyrimidine [HMP] phosphate synthase) branch. Here we found that archaeal Thi4 and ThiC were encoded by leaderless transcripts, ruling out a riboswitch mechanism. Instead, a novel ThiR transcription factor that harbored an N-terminal helix-turn-helix (HTH) DNA binding domain and C-terminal ThiN (TMP synthase) domain was identified. In the presence of thiamine, ThiR was found to repress the expression of thi4 and thiC by a DNA operator sequence that was conserved across archaeal phyla. Despite having a ThiN domain, ThiR was found to be catalytically inactive in compensating for the loss of ThiE (TMP synthase) function. In contrast, bifunctional ThiDN, in which the ThiN domain is fused to an N-terminal ThiD (HMP/HMP phosphate [HMP-P] kinase) domain, was found to be interchangeable for ThiE function and, thus, active in thiamine biosynthesis. A conserved Met residue of an extended α-helix near the active-site His of the ThiN domain was found to be important for ThiDN catalytic activity, whereas the corresponding Met residue was absent and the α-helix was shorter in ThiR homologs. Thus, we provide new insight into residues that distinguish catalytic from noncatalytic ThiN domains and reveal that thiamine biosynthesis in archaea is regulated by a transcriptional repressor, ThiR, and not by a riboswitch.

IMPORTANCE Thiamine pyrophosphate (TPP) is a cofactor needed for the enzymatic activity of many cellular processes, including central metabolism. In archaea, thiamine biosynthesis is an apparent chimera of eukaryote- and bacterium-type pathways that is not well defined at the level of enzymatic steps or regulatory mechanisms. Here we find that ThiN is a versatile domain of transcriptional repressors and catalytic enzymes of thiamine biosynthesis in archaea. Our study provides new insight into residues that distinguish catalytic from noncatalytic ThiN domains and reveals that archaeal thiamine biosynthesis is regulated by a ThiN domain transcriptional repressor, ThiR, and not by a riboswitch.

KEYWORDS: thiamine biosynthesis, transcription factor (ThiR), archaea, cofactor metabolism

INTRODUCTION

Thiamine is a water-soluble vitamin (B1), and its derivative, thiamine pyrophosphate (TPP), is a cofactor required for the enzyme activities of many cellular processes, such as glycolysis (pyruvate dehydrogenase [EC 1.2.4.1] in bacteria and pyruvate-ferredoxin oxidoreductase [EC 1.2.7.1] in halophilic archaea), the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle (α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase [EC 1.2.4.2] in bacteria and α-ketoglutarate–ferredoxin oxidoreductase [EC 1.2.7.3] in halophilic archaea), and the pentose phosphate pathway (transketolase [EC 2.2.1.1] in bacteria). Thiamine consists of a thiazole [5-(2-hydroxyethyl)-4-methylthiazole (THZ)] and a pyrimidine (2-methyl-4-amino-5-hydroxymethylpyrimidine [HMP]). These moieties are synthesized by two separate branches regardless of the organism and require about 16 genes for their de novo biosynthesis (1, 2) (Fig. 1A). Once the thiamine precursors are phosphorylated to THZ phosphate (THZ-P) and HMP pyrophosphate (HMP-PP), the molecules are condensed to form TMP by a TMP synthase (TPS) of the ThiE type (THI6 N domain) or the ThiN type (EC 2.5.1.3). Thiamine pyrophosphate (TPP), the biologically active form of thiamine, is produced from TMP by the kinase ThiL.

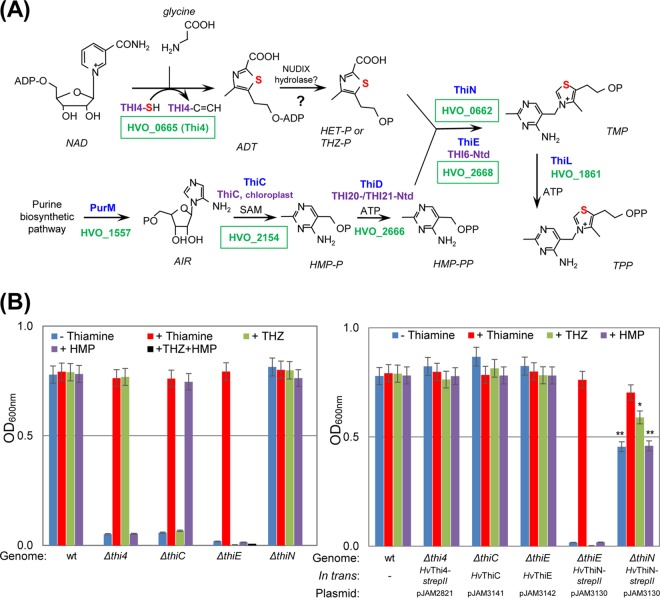

FIG 1.

De novo pathway of thiamine biosynthesis in H. volcanii and growth assay. (A) Thiamine biosynthesis in H. volcanii is a hybrid of bacterium-like pyrimidine (bottom) and eukaryote-like thiazole (top) synthesis pathways. The sulfur atom associated with the formation of the thiazole ring is highlighted in red. Thiamine-biosynthetic enzymes of bacteria, yeast, and H. volcanii are indicated in blue, purple, and green, respectively. Homologs of H. volcanii characterized in this study are shown in green boxes. (B) The single-gene deletion mutants and trans-complemented strains were grown in minimal medium (GMM) without (−) or supplemented with (+) thiamine, THZ, and/or HMP, where strepII indicates a C-terminal Strep-tag II fusion. Growth was monitored as the OD600. Data represent mean results ± standard errors of the means from three independent experiments (n = 3). P values were determined by two-tailed, unpaired Student's t test (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01). See Materials and Methods for details. Abbreviations: ADT, ADP-thiazole; THZ-P or HET-P, 4-methyl-5-(β-hydroxyethyl)thiazole phosphate; AIR, 5-aminoimidazole ribotide; SAM, S-adenosyl-methionine; HMP-P, 4-aminohydroxymethyl-2-methylpyrimidine phosphate; HMP-PP, 4-aminohydroxymethyl-2-methylpyrimidine pyrophosphate; TMP, thiamine monophosphate; TPP, thiamine pyrophosphate.

The expression of key genes of thiamine biosynthesis is regulated by a riboswitch mechanism in bacteria and eukaryotes (3–5). Riboswitches are regulatory elements in mRNA composed of (i) an aptamer that binds small metabolites, such as TPP, and (ii) an expression platform that transduces ligand binding to control target gene expression. The finding that thiamine biosynthesis genes (thiC and thiM) from Escherichia coli are regulated by a riboswitch is the first representative model of how small metabolites can bind mRNA and modulate gene expression (6). In this model, TPP is recognized by a conserved RNA structure called the THI (thiamine) box in the 5′ untranslated region (UTR) of mRNAs encoding ThiC and ThiM. Ligand binding triggers a conformational change in the mRNA secondary structure that results in the formation of a stem-loop, which inhibits the initiation of translation by masking the Shine-Dalgarno (SD) sequence (6, 7). The sole example of a riboswitch in eukaryotes appears to be the highly conserved TPP-regulated THI box as discovered in bacteria; however, the regulation of target gene expression is performed in a different manner, i.e., alternative mRNA splicing (4, 5, 8). TPP binding to the THI box prevents pairing to the correct splice donor (GU) and acceptor (AG), and processing from this alternative splice donor produces aberrantly long mRNAs or prematurely truncated proteins, which yield low expression levels of thiamine biosynthesis gene (thiC and thi4) products in eukaryotes (4, 5, 9).

Besides the riboswitch, thiamine biosynthesis is also regulated by three positive regulatory factors in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: Thi2p, Thi3p, and Pdc2p. Evidence to support this regulation includes the finding that ΔTHI2 and ΔTHI3 mutations significantly reduce the expression levels of thiamine biosynthesis “THI” genes (i.e., THI4, THI5, THI6, PHO3, and THI80) (10–12). Further studies revealed that Thi2p contains an N-terminal Zn2-Cys6 domain that binds DNA upstream of the THI genes (13) and that Thi3p harbors a motif, Gly-Asp-Gly-X24–27-Asn-Asn (where X is any amino acid residue), which is an apparent TPP sensor in the regulation of THI gene expression (14). Thi3p directly binds not only Thi2p but also Pdc2p, the third THI gene activator (14). Pdc2p interacts with the promoter regions of the THI and PDC5 genes (the latter of which encodes a minor isoform of the TPP-dependent pyruvate decarboxylase) (15). Thus, Pdc2p along with Thi2p and Thi3p are implicated in the transcriptional regulation of THI and TPP-dependent genes.

Recent studies identified how thiamine is synthesized de novo in archaea. Archaea synthesize the thiazole ring of TPP by a eukaryote-like THI4 mechanism (16–18). However, the pathway for the production of the HMP moiety of TPP and the regulation of thiamine biosynthesis gene expression in archaea remain unclear. In this paper, we demonstrate that thiamine biosynthesis is carried out by a chimera of the eukaryote-like THI4 pathway to synthesize the thiazole ring with a bacterial ThiC-like pathway to synthesize the pyrimidine (HMP) moiety in the archaeon Haloferax volcanii. In addition, we discovered a novel regulatory protein, ThiR, which has a xenobiotic responsive element (XRE)-type helix-turn-helix (HTH) DNA binding domain (XRE_HTH) fused to a ThiN domain. ThiR is found to be a transcriptional repressor of the expression of thi4 and thiC. ThiR homologs are widespread in archaea, suggesting that the regulation of these thiamine biosynthesis genes is governed by a repressor protein and not by a riboswitch or activation mechanism.

RESULTS

Haloferax volcanii ThiC and ThiE, but not ThiN, are required for thiamine biosynthesis.

To further understand thiamine biosynthesis in archaea, the genes encoding the ThiC, ThiE, and ThiN homologs were deleted from the H. volcanii genome (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), and the resulting mutant strains, including the Δthi4 mutant, a known thiamine auxotroph (16), were analyzed for thiamine-dependent growth. Based on these growth assays, the Δthi4, ΔthiC, and ΔthiE mutants displayed thiamine auxotrophy (Fig. 1B, left). The observed phenotypes for the Δthi4, ΔthiC, and ΔthiE mutants were not due to polar mutations, as these strains were restored to wild-type (wt) growth by the expression of the corresponding thi4, thiC, and thiE genes in trans (Fig. 1B, right). In contrast, H. volcanii ThiN (HvThiN) was found to be unnecessary for growth since the ΔthiN mutant grew similarly to the wt in the absence of thiamine (Fig. 1B). Interestingly, the overexpression of the HvThiN homolog in H. volcanii could not substitute for thiE function as an expected TPS enzyme (Fig. 1B). Moreover, the growth of the ΔthiN mutant was reduced by the trans-expression of HvThiN (with the exception of thiamine-supplemented medium) (Fig. 1B, right), suggesting that HvThiN plays a role in thiamine metabolism that is distinct from biosynthesis. Further analysis by feeding with thiamine-biosynthetic precursors revealed that HMP (not THZ) supported the growth of the ΔthiC mutant, while the growth of the ΔthiE mutant was restored only in the presence of thiamine and was not restored in the presence of HMP and/or THZ medium (Fig. 1B). Based on these results, H. volcanii ThiC and ThiE were apparent HMP-P and TMP synthases, respectively. In contrast, HvThiN could not function in the synthesis of TMP, as this homolog was not needed for thiamine biosynthesis and was unable to substitute for ThiE function, even when ectopically expressed from a constitutive rRNA P2rrnA promoter.

ThiR, a ThiN domain protein that regulates the transcriptional expression of thiamine-biosynthetic genes.

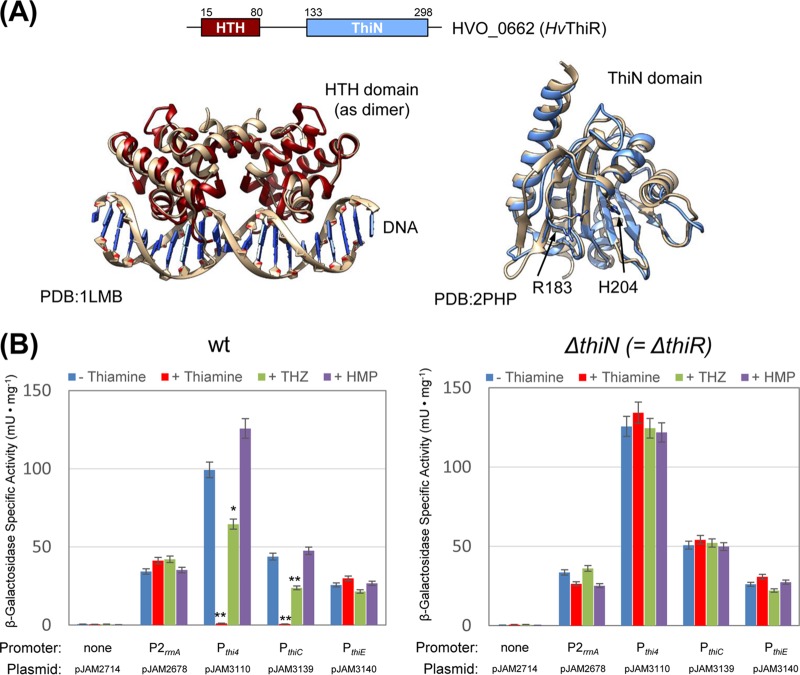

While the active-site residues of the ThiN-like TPS enzyme reported for the condensation of THZ-P and HMP-PP were conserved in HvThiN (19), our results clearly demonstrated that the product of the thiN gene was not required for catalyzing thiamine biosynthesis and could not compensate for the loss of thiE function in H. volcanii. HvThiN is naturally fused to an N-terminal HTH DNA binding domain predicted by homology modeling to be structurally related to XRE-type (XRE_HTH) transcriptional repressors of bacteriophages cro, CI, and lambda (Fig. 2A) and SopB-type HTH DNA binding proteins (see Discussion). Thus, HvThiN may function as a transcriptional regulator that senses thiamine levels instead of a catalytic enzyme. To investigate this possibility, the DNA region immediately 5′ of the start codon of the thiamine-biosynthetic genes (thi4, thiC, and thiE) was fused to a β-galactosidase reporter (bgaH) gene to allow transcription/translation to be monitored by a colorimetric assay. The 5′ regions (denoted Pthi4, PthiC, and PthiE) included transcription factor B (TFB)-responsive element (BRE)/TATA box promoter consensus sequence elements but no predicted riboswitch or 5′ UTR that could be detected by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) analysis of the 5′- to 3′-end ligated transcripts (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). This finding was not surprising, as leaderless transcripts are common to haloarchaea (20, 21). An initial analysis was performed in wt cells to assess whether thiamine and/or its metabolic precursors could influence reporter gene expression. Reporter gene expression by PthiC and Pthi4 was found to be repressed by growth in medium supplemented with thiamine and THZ (reduced by 46 and 35%, respectively) compared to that in the absence of thiamine or the presence of HMP (which was similar to that of the wt), while there was little if any significant influence on the expression of PthiE and P2rrnA promoter control (Fig. 2B, left). Further analysis revealed that the deletion of thiN caused a significant derepression of gene expression from PthiC and Pthi4 under conditions of high thiamine or THZ levels (Fig. 2B, right). Thus, while HvThiN lacked metabolic activity, it was needed for the repression of thi4 and thiC when cells were grown in the presence of thiamine and THZ. Thus, we recommend the reannotation of HvThiN (HVO_0662) as “ThiR.” Our results reveal that in H. volcanii, the thi4 and thiC promoter regions are repressed by ThiR in the presence of thiamine and THZ (presumably by binding the molecular effector TMP or TPP) but not HMP. In contrast, thiamine and its metabolic precursors have no effect on expression from PthiE.

FIG 2.

ThiR structure and identification of its target promoters. (A) ThiR domain architecture and 3D structural models. Data under PDB accession numbers 1LMB and 2PB9 and other homologs were used as the template to build the model. The ribbon diagrams include the N-terminal HTH domain of ThiR (dark red) overlaid with the lambda repressor-operator complex (brown) (PDB accession number 1LMB), represented as a dimer (left), and the ThiN domain of ThiR (light blue) overlaid with the ThiN domain of Methanocaldococcus jannaschii ThiDN (brown) (PDB accession number 2PHP) (right). (B) A reporter gene (bgaH) assay was performed by using wild-type (wt) and ΔthiN (ΔthiR) mutant cells carrying transcriptional fusion constructs of promoters. Cells were grown to log phase in GMM with and without thiamine, THZ, or HMP, as indicated. The cell lysate (5 μg of total protein) was used in the assay. Experiments were performed in triplicate (n = 3), and data represent mean results ± standard errors of the means. P values were determined by two-tailed, unpaired Student's t test (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01). See Materials and Methods for details.

ThiR-regulated thiamine-biosynthetic genes share common promoter elements.

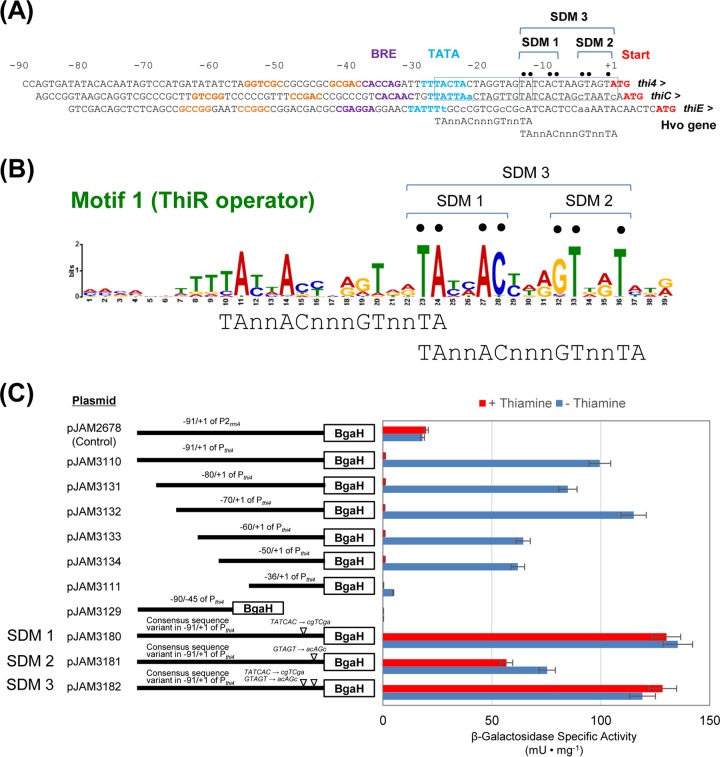

DNA operators within the promoter region were likely responsible for the observed ThiR-mediated repression in the presence of thiamine. Thus, the DNA sequence of the region 5′ of the ATG start codon of thi4 and thiC was analyzed and compared to that of thiE to discover consensus motifs that may be common to these ThiR-regulated genes. Based on this comparison, a putative ThiR operator sequence was identified 5′ of the start codon and 3′ of the BRE/TATA promoter elements of thi4 and thiC (Fig. 3A). The putative ThiR operator region was investigated, and a consensus sequence motif was identified immediately 5′ of the start codons of thi4, thiC, and cytX (HMP transporter) homologs from halophilic and hyperthermophilic Euryarchaeota, suggesting that the DNA sequence is a common binding site for the transcriptional repression of thiamine metabolism in archaea (Fig. 3B; see also Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). The putative ThiR operator motif included two palindromic repeats of TAn2ACn3GTn2TA (where n is any nucleotide), with the first palindrome overlapping the TATA consensus sequence and the second being in close proximity to the translation/transcription start site. The position of the palindromes suggested that the binding of ThiR to either or both sites would disrupt gene expression. The sequence cAn2ACn3aan2TA, where uppercase letters correspond to bases in the palindrome 5′ of thi4 and thiC, was found upstream of H. volcanii thiE. However, the Tn2T motif was read as an2T upstream of thiE, which may make it inactive (Fig. 3B).

FIG 3.

Regions upstream of archaeal thiamine biosynthesis genes and identification of a conserved operator motif controlled by ThiR. (A) Regions upstream of H. volcanii thi4, thiC, and thiE were analyzed for conserved sequences that may function as ThiR binding sites and promoter elements, including the TFB-responsive element (BRE) (purple) and the TATA box (blue) (based on the BRE and TATA consensus sequences CRnAAT and TTTAWA, respectively, where W is A or T, R is A or G, and n is any nucleotide base). Inverted repeats 5′ of the promoter not needed for ThiR-mediated control are indicated by yellow letters. The translation start codon is indicated in red. Sites of site-directed mutagenesis (SDM) are indicated above the DNA sequence by black dots. Palindromic repeats of TAn2ACn3GTn2TA 5′ of the thi4 and thiC genes are boxed. A region 5′ of thiE with nucleotides found to vary from the palindrome, in lowercase type, is aligned for comparison. Numbers above the sequence indicate positions relative to the translation/transcription start site of thi4. (B) Conserved motif identified 5′ of the thiamine biosynthesis (thiC and thi4) and HMP transporter (cytX) gene homologs using MEME (see Table S3 in the supplemental material for details). (C) Reporter gene (bgaH) assay with systematically reduced thi4 promoter regions. Numbers above the black bars indicate the promoter length from the ATG start codon. ▽ indicates the sequences modified in the predicted ThiR operator. Cell-free lysates (5 μg of total protein) from wild-type strains carrying the thi4 promoter variants that were grown to log phase in GMM with and without thiamine were used for the reporter assay as indicated. Experiments were performed in triplicate (n = 3), and data represent mean results ± standard errors of the means. See Materials and Methods for all experimental details.

To demonstrate the minimal DNA operator sequence needed for the ThiR-mediated repression of thi4 expression, Pthi4 was systematically deleted and analyzed by site-directed mutagenesis (SDM) for its ability to drive gene expression. Although the DNA sequence 5′ of the BRE/TATA consensus included some inverted repeats, this region was not responsible for the thiamine regulation of Pthi4 (Fig. 3C). Instead, the region spanning nucleotides (nt) −50 to −1 (where +1 is the transcription/translation start site), which included the BRE/TATA promoter elements and the putative ThiR operator, was found to be sufficient for regulating Pthi4 expression in a thiamine-dependent manner (Fig. 3C). Site-directed mutagenesis of the putative ThiR operator motif was performed and revealed that this conserved DNA sequence element was important for thiamine-dependent gene expression (Fig. 3C). The BRE/TATA consensus of the ThiR operator variants could still drive Pthi4 expression but did so constitutively, irrespective of thiamine. This finding supports the model that ThiR binds the operator in the presence of the molecular effector TMP or TPP, resulting in the transcriptional repression of the thi4 and thiC thiamine biosynthesis genes in archaea such as H. volcanii.

ThiN domain function.

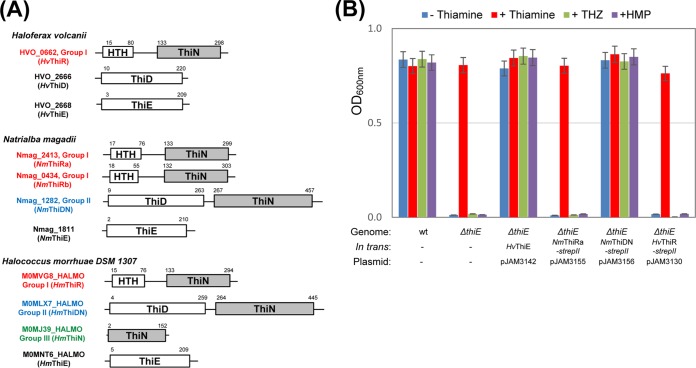

Proteins of the thiamine phosphate synthase ThiN (IPR019293) family are common to bacteria and archaea. Based on the domain architecture, we found that the ThiN domain proteins cluster into three major groups: group I had an N-terminal DNA binding domain (ThiR type) and was restricted to archaea (Fig. 4A), group II included an additional N- or C-terminal catalytic domain (ThiD, PurM/L, or HIT) (Fig. 4A), and group III was composed of the ThiN domain alone.

FIG 4.

Characterization of ThiN domain group I and II proteins. (A) Structural architecture of ThiD, ThiE, and ThiN domain-containing proteins in select haloarchaea. (B) The ΔthiE thiamine auxotroph and its trans-complemented strains were grown in minimal medium (GMM) supplemented with or without thiamine, THZ, or HMP, where strepII indicates a C-terminal Strep-tag II fusion. Growth was measured as the OD600. Data represent mean results ± standard errors of the means from three independent experiments (n = 3).

Interestingly, many archaea were found to harbor redundant ThiN (group II/III) domain homologs besides ThiE and, thus, may use two distinct isoenzymes to catalyze the condensation step of TPP biosynthesis (Table 1). The haloarchaeon Natrialba magadii was chosen to highlight this point since N. magadii encodes conserved ThiE and ThiDN (group II) proteins in addition to two ThiR-type transcription factor-type homologs (group I) (Fig. 4A; see also Fig. S4 in the supplemental material, which highlights the ThiE homology). To determine whether or not a ThiDN protein can replace ThiE for the TPS catalytic function compared to ThiR, the ThiDN gene homolog (Nmag_1282) of N. magadii was expressed in the H. volcanii ΔthiE thiamine auxotroph. The ΔthiE mutant was complemented for growth by the expression of N. magadii ThiDN (NmThiDN) in the absence of thiamine, THZ, or HMP (Fig. 4B). In contrast, the ThiR homologs of Nmag_2413 (NmThiRa) and HVO_0662 (HvThiR), while confirmed to be expressed in vivo at the protein level (Fig. S5), were unable to recover the growth of the ΔthiE mutant (Fig. 4B). Thus, H. volcanii does not naturally use the ThiN domain of HvThiR for the TPS activity required for the thiamine biosynthesis pathway but can use ThiDN (group II) enzymes to replace TPS function through metabolic engineering. Our findings suggest that certain archaea regulate the condensation step of thiamine biosynthesis by the use of two distinct isoenzymes (ThiE and ThiDN), with the latter often being fused to a ThiD domain, which may minimize the release of metabolic intermediates, such as HMP-PP, during thiamine biosynthesis.

TABLE 1.

Distribution of THI box and thiamine biosynthesis gene homologs in archaeaa

| Archaeal phylum (no. of species) | No. of gene homologs (group) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ThiN | ThiE | THI box | Thi4 | ThiC | |

| Euryarchaeota (313) | 188 (I) | 236 | 10 | 255 | 393 |

| 173 (II) | |||||

| 48 (III) | |||||

| DPANN (1) | — | — | 1 | — | — |

| Lokiarchaeota (1) | — | — | — | — | 2 |

| Korarchaeota (2) | 1 (II) | — | 1 | 1 | — |

| Crenarchaeota (82) | 165 (I) | 9 | — | 61 | 47 |

| 71 (II) | |||||

| 31 (III) | |||||

| Thaumarchaeota (32) | 3 (I) | 1 | — | 26 | 27 |

| 25 (II) | |||||

| 3 (III) | |||||

| Bathyarchaeota (6) | 2 (II) | — | — | 5 | 6 |

Numbers of species in each archaeal phylum with identified homologs and the ThiN group (I, II, or III) are indicated in parentheses. —, homologs not predicted. Of the 12 putative THI boxes, only the THI box of Methanocorpusculum labreanum Z is predicted to be located upstream of a thiamine biosynthesis homolog (Thi4). The other THI boxes are predicted to be located upstream (5′) of major facilitator superfamily (IPR011701) gene homologs (see Table S3 in the supplemental material for details).

Residues of the ThiN domain of N. magadii ThiDN that are essential for TPS activity.

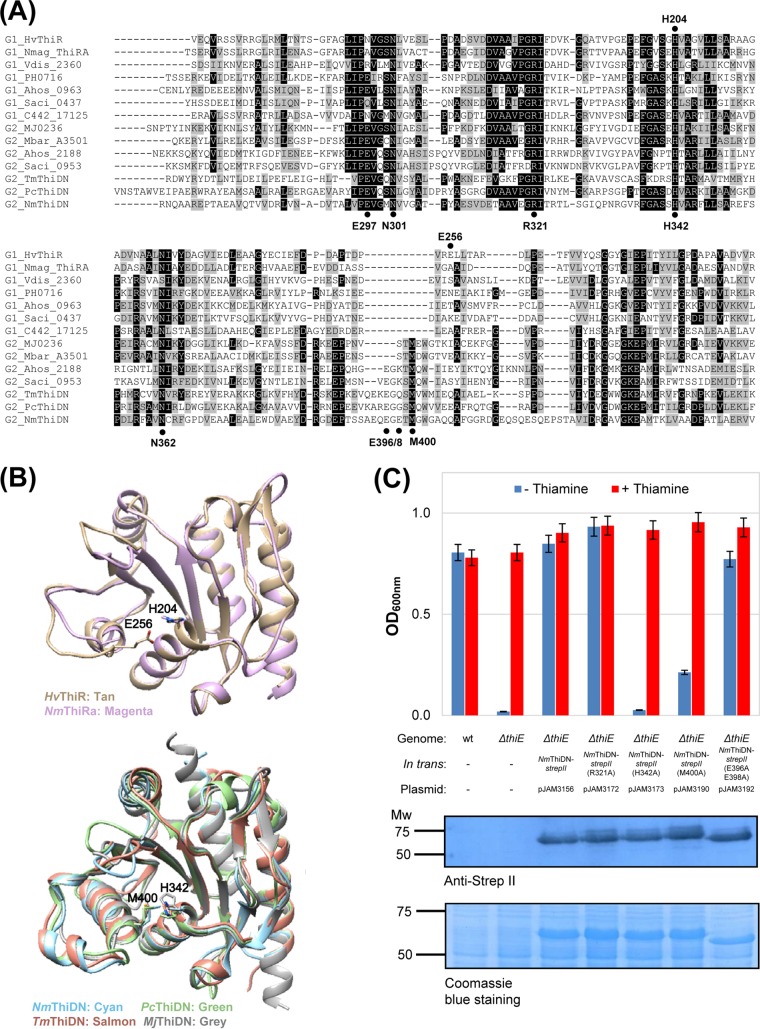

A previous study using site-directed mutagenesis and in vitro assays revealed that conserved Arg320 and His341 residues are required for the TPS activity of Pyrobaculum calidifontis ThiDN (analogous to Arg321 and His342 of N. magadii ThiDN, with the latter numbering being used in this study) (19). However, the current understanding of residues critical for the ThiN domain-mediated condensation of THZ-P and HMP-PP to TMP is limited since the two residues (Arg321 and H342) are conserved in ThiN domains regardless of their classification into group I or II, with the ThiR type (group I) being found to be catalytically inactive by our study (Fig. 4B and 5A). To further understand conserved active-site residues that are crucial for catalytic activity, the ThiN domains of the ThiDN fusion proteins (group II) were compared to those of the ThiR-type transcription factors by amino acid sequence alignment and three-dimensional (3D) structural homology modeling. Based on the 3D model combined with multiple-amino-acid sequence alignment, an additional 6 to 11 residues in ThiDN formed a relatively long α-helix near the conserved His342 residue (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, among these additional residues, Met400 was found to be highly conserved in ThiDN but not ThiR homologs (Fig. 5A and B). Residues that appeared to distinguish the ThiN catalytic (group II) from noncatalytic (group I) domains were subjected to amino acid exchange, and activity was analyzed by the complementation of a ΔthiE mutant for growth under thiamine-minus conditions. The growth of the ΔthiE strain was fully restored by the expression of NmThiDN variants, such as E297A, N301A, R321A, N362A, E396A and/or E398A, or K434A, but not by H342A or M400A variants (Fig. 5C; see also Fig. S6 in the supplemental material). Further analysis by Western blotting revealed that the absence of ΔthiE complementation was not due to a lack of protein production, as the NmThiDN H342A and M400A variants were found to be present at levels similar to those of the wild type (Fig. 5C, bottom). Thus, Met400 of the extended α-helix and His342 were found to be important for ThiDN (group II) function, while the other conserved residues (including Arg321) were not essential for TPS activity, based on in vivo assays.

FIG 5.

Characterization of conserved residues in the ThiN domain. (A) Alignment of group I (ThiR-type) and group II (ThiDN-type) ThiNs from select archaea. HvThiR, Haloferax volcanii ThiR (UniProt accession number D4GSS2); Nmag_2413, Natrialba magadii ThiRa (accession number D3SXM5); Vdis_2360, Vulcanisaeta distribute (accession number E1QR38); PH0716, Pyrococcus horikoshii (accession number O58447); Ahos_0963, Acidianus hospitalis (accession number F4B956); Saci_0437, Sulfolobus acidocaldarius (accession number Q4JBI0); C442_17125, Haloarcula amylolytica (accession number M0K891); MJ0236, Methanocaldococcus jannaschii ThiDN (MjThiDN) (accession number Q57688); Mbar_A3501, Methanosarcina barkeri (accession number Q465S0); Ahos_2188, A. hospitalis (accession number F4B936); Saci_0953, S. acidocaldarius (accession number Q4JA65); TmThiDN, Thermotoga maritima ThiDN (Tm_0790) (accession number Q9WZP7); PcThiDN, Pyrobaculum calidifontis ThiDN (Pcal_0240) (accession number A3MSR0); NmThiDN, N. magadii ThiDN (accession number D3SSD6). Protein sequences were aligned by using ClustalW. Prior to dendrogram construction, extensive gaps and N- and C-terminal extensions were removed by using BioEdit. Amino acid residues noted are from HvThiR (top) and NmThiDN (bottom). (B) 3D structural models of ThiN domain proteins of group I (top) and group II (bottom). Residues are numbered according to HvThiR (top) and NmThiDN (bottom). The crystal structure of MjThiDN (PDB accession number 2PHP) was used for comparison. The structures are shown in ribbon mode. The conserved His “active site” and proximal residues are indicated with numbering according to the numbering for HvThiR (top) and NmThiDN (bottom). ThiN domain proteins in the ribbon diagram include HvThiR, NmThiRa, NmThiDN, PcThiDN, and TmThiDN. (C) Site-directed mutagenesis analysis of ThiN domain proteins. The ΔthiE thiamine auxotroph and strains complemented in trans were grown in minimal medium (GMM) supplemented with or without thiamine, THZ, or HMP, where strepII indicates a C-terminal Strep-tag II fusion. Growth was measured as the OD600, when cells reached stationary phase (OD600 of 0.8 to 1.0). Data represent mean results ± standard errors of the means from three independent experiments (n = 3). The production of the variants of NmThiDN–Strep-tag II (theoretical molecular mass, 49 kDa) proteins was detected by anti-Strep-tag II Western blotting (0.065 OD600 units of cells per lane). Equivalent protein loading was assessed by parallel SDS-PAGE gels with Coomassie blue R-250. Growth and measurement are described in Materials and Methods. Mw, molecular weight.

DISCUSSION

Chimeric thiamine biosynthesis pathway in archaea.

In the early 2000s, thiamine biosynthesis genes from a number of prokaryotic genomes were compared (22). Comparative genome analysis found that many bacteria have ThiC homologs for the synthesis of the pyrimidine moiety and ThiF-ThiS-ThiG-ThiH homologs for the production of the thiazole ring. Most bacteria also have ThiE for the condensation of THZ-P and HMP-PP to form TMP. Archaea also harbor ThiC homologs but are missing important steps of the ThiF-ThiS-ThiG-ThiH pathway needed to synthesize the thiazole ring. Instead, archaea use Thi4 to mobilize sulfur to form the thiazole ring by two apparent mechanisms: (i) iron-dependent sulfide transfer or (ii) a mechanism in which an active-site cysteine serves as a sulfide source and is inactivated after a single turnover, similarly to eukaryotic THI4. The iron-dependent sulfide transfer mechanism is demonstrated by Methanocaldococcus jannaschii Thi4, which has a conserved His residue replacing the active-site Cys and catalyzes the formation of adenylated thiazole (ADT) by using exogenous sulfide (17). In contrast, the haloarchaea and thaumarchaeota have Thi4 homologs with a conserved active-site Cys required for ADT synthesis (16). The archaeal Thi4 mechanisms are not interchangeable based on the finding that a Δthi4 mutation of H. volcanii cannot be trans-complemented by the expression of the Thi4 C165H mutation (with the active-site Cys being exchanged with His) in the presence of several sulfur sources (see Fig. S7 in the supplemental material). Thus, archaeal thiazole ring synthesis is generated from two different sulfur sources depending on the conserved residue in the Thi4 active site.

As discussed above, many archaea are predicted to synthesize thiamine from ThiC- and Thi4-generated precursors; however, these key enzymes are not predicted for a few archaeal groups such as the DPANN (Diapherotrites, Parvarchaeota, Aenigmarchaeota, Nanohaloarchaeota, and Nanoarchaeota) group (NCBI taxid 1783276) and Lokiarchaeota (Table 1; see also Table S3 in the supplemental material). Thus, the latter archaea either require externally supplied thiamine or thiamine precursors for growth or carry out thiamine biosynthesis by an unknown mechanism.

N-terminal HTH DNA binding domain of ThiR.

One major type of transcription factor has an HTH motif (23) consisting of three to six α-helices, which plays an important role in binding to DNA. Based on homology modeling, ThiR has an N-terminal HTH motif (amino acids [aa] 1 to 106) structurally related to XRE-type transcriptional repressors (e.g., bacteriophages lambda, cro, and CI) and SopB (Protein Data Bank [PDB] accession number 3MKY), the latter of which binds centromeres by an HTH motif during DNA segregation (24). Interestingly, ThiR and SopB have different cellular functions, repressor and DNA segregation, respectively, yet similar HTH structures (see Fig. S8A in the supplemental material). SopB has seven α-helices in its central region (aa 155 to 272) and, as in many DNA binding proteins with HTH motifs, mediates DNA binding by α2- and α3-helices (25). The α2- and α3-helices of ThiR are also predicted to localize near DNA (Fig. S8A). In addition, the α3-helix of ThiR has a positive electrostatic potential mediated by Lys47 similarly to the positively charged amino acid Arg195 of SopB (Fig. S8A to C). Transcription factors are inclined to harbor positively charged residues, such as Lys and Arg, that form a surface patch of positive electrostatic potential at the DNA binding interface (26, 27). Interestingly, ThiR has a more positive potential than does SopB in the putative DNA binding patch by supplying Arg71 in the α5-helix (Fig. S8A to C). SopB recognizes its target DNA by two mechanisms: sequence specifically and nonspecifically (24). In the sequence-specific mode, SopB recognizes the GC-rich palindrome GGGACCn2GGTCCC, with five positively charged amino acid residues in the α2- and α3-helices (24). In contrast, ThiR has its positively charged residues in the α3- and α5-helices and represses thi4 and thiC gene expression through an apparent TAn2ACn3GTn2TA motif, which is also palindromic but less GC rich than the binding site of SopB.

ThiN domain-containing proteins in archaea.

ThiE-type thiamine phosphate synthase condenses THZ-P and HMP-PP to TMP in bacteria (ThiE) and eukaryotes (THI6 N domain) but is not universally distributed (22) (Table 1). ThiE activity is replaceable for the coupling of THZ-P and HMP-PP by ThiDN (group II) and YjbQ, the latter of which has cryptic enzymatic activity (28, 29). Interestingly, the ThiN domain of the ThiR-type group I proteins does not catalyze TPS activity (Fig. 1B and 4B), whereas ThiN group II proteins are active, based on results of growth assays (Fig. 4B) and data from previous studies (19, 28). This finding is surprising in that the ThiN domains of group I and II proteins have relatively high sequence similarity (e.g., 39% in N. magadii), including conserved residues predicted to function in catalytic activity (e.g., Glu297, Arg321, and His342 in NmThiDN). Previous work revealed that the conserved His342 and Arg321 residues are important for ThiN group II activity as determined by in vitro assays (19). However, this feature alone does not explain why ThiN group I proteins are catalytically inactive, since these two residues are conserved regardless of classification into group I or II (Fig. 5A). Here, by in vivo assays, we confirm that His342 is needed but find (in contrast) that Arg321 is not essential for ThiN group II catalytic activity. Importantly, we identify a conserved residue (Met400) within an extended α-helix within the ThiN domain of group II (ThiDN-type) proteins that is proximal to His342 and important for catalytic activity; this extended α-helix is not found in the ThiN domains of group I (ThiR-type) proteins. Instead, the catalytically inactive ThiR-type proteins are modeled to have a short α-helix near the conserved His342 residue (Fig. 5B). Thus, the extended α-helical structure appears important for the TPS activity of group II (ThiDN-type) proteins.

While the function of the catalytically inactive ThiN domain of archaeal ThiR (group I) remains to be directly answered, our work reveals that ThiR is needed for the repression of thiC and thi4 gene expression under thiamine-rich conditions (Fig. 2B). We hypothesize that the “inactive” ThiN domain of ThiR recognizes the concentration of TMP or TPP and transduces this signal to DNA binding. Previous studies show that Asn residues in pyruvate decarboxylase play a key role in TPP binding (30) and that Thi3p, which is a positive transcriptional factor in yeast, recognizes TPP by a specific Asn-containing motif, Gly-Asp-Gly-X24–27-Asn-Asn (where X is any amino acid residue) (14). Multiple Asn residues are located near the His342 active site regardless of the ThiN domains of group I and group II (Fig. 5A), suggesting that ThiR recognizes TMP or TPP by its ThiN domain, which could mediate a conformational change (subunit dimerization and/or HTH orientation) for DNA binding.

ThiR is one of the three major groups of ThiN domain proteins in archaea.

Our work suggests that most archaea use a ThiR-type DNA binding protein instead of a THI box riboswitch to regulate thiamine biosynthesis. Phylogenetic analysis reveals that archaea with ThiR homologs have TPS enzyme homologs, suggesting thiamine biosynthesis, but are devoid of any type of THI box riboswitch motif (RF00059 family) (Table 1; see also Table S3 in the supplemental material). In fact, THI box motifs were found to be quite limited in archaea, with most archaeal THI box motifs being located 5′ of major facilitator superfamily (IPR011701) gene homologs, which may be involved in thiamine salvage pathways (Table 1 and Table S3). One exception was a THI box motif located 5′ of the thiazole synthase gene homolog (thi4) of the methanogen Methanocorpusculum labreanum. Among archaeal phyla, the Euryarchaeota, Crenarchaeota, and Thaumarchaeota had the greatest diversity of ThiN/E homologs and THI box motifs, suggesting evolutionary flexibility (Table 1). In contrast, the Lokiarchaeota, DPANN, and Geoarchaeota phyla/groups had no apparent TPS enzyme homologs, suggesting that TMP is synthesized by an alternative mechanism and/or is taken up from the environment. Of the ThiR homologs identified, all were exclusive to the phyla Euryarchaeota, Crenarchaeota, and Thaumarchaeota, with 60% belonging to the class Halobacteria and the remaining belonging to the class Thermococci or Thermoprotei (Table S3). Thus, compared to the prevalent THI box riboswitches used to regulate thiamine metabolism in bacteria, plants, fungi, and algae (31), ThiR-type transcription factors displayed a cooccurrence with thiamine-biosynthetic gene homologs and appeared to be more common than canonical THI box riboswitches in the regulation of thiamine biosynthesis in archaea.

Implications for regulation of thiamine biosynthesis.

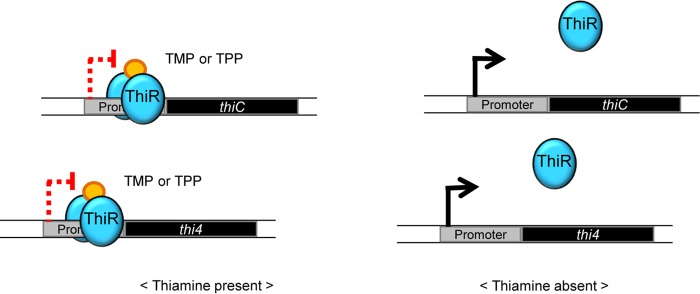

Depending on the concentration of thiamine available in the medium, thiamine biosynthesis genes such as thi4 and thiC from H. volcanii are regulated by the novel regulatory protein ThiR and not by a riboswitch or a transcriptional activator. In the presence of TMP or TPP (phosphorylated and biologically active derivatives of thiamine), ThiR is proposed to bind to its specific operator sequence (Fig. 3). Consequently, the promoter and the transcription start site may not be accessible to RNA polymerase (Fig. 6). In contrast, when cells are depleted of thiamine, ThiR may no longer bind to the operator site(s), resulting in the recruitment of RNA polymerase to the promoter and the transcription of key genes of thiamine biosynthesis.

FIG 6.

Proposed model for the regulation of thiamine biosynthesis gene transcription by ThiR. The diagram shows that ThiR recognizes its operator region upstream of thi4 and thiC in the presence of thiamine (presumably by binding TMP or TPP), while ThiR is not bound in the absence of thiamine in the growth medium. The presumed molecular effectors (TMP or TPP) and ThiR are represented in yellow and blue, respectively.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

HMP was purchased from Matrix Scientific (Columbia, SC). Other biochemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), and organic and inorganic analytical-grade chemicals were obtained from Fisher Scientific (Atlanta, GA). Restriction endonucleases and T4 DNA ligase were obtained from New England BioLabs (NEB) (Ipswich, MA). Desalted oligonucleotides were ordered from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA).

Strains, media, and growth conditions.

Details of strains and primer sequences used in this study are listed in Tables S1 and S2 in the supplemental material. The general growth conditions for Escherichia coli and H. volcanii strains were described previously (16). To monitor de novo thiamine biosynthesis, H. volcanii strains were grown in 4 ml complex medium (ATCC 974) to log phase (optical density at 600 nm [OD600] of 0.4 to 0.5), washed two times with “thiamine-minus” medium (glycerol minimal medium [GMM]) by centrifugation (8,600 × g for 2 min at room temperature), and subcultured to a starting OD600 of 0.02 for growth assays in 4 ml of GMM supplemented with thiamine (2.66 μM), THZ (2 μM), or HMP (2 μM). Once the cells reached late log phase (OD600 of 0.8 to 1.0), the cell culture (10 μl) was transferred into fresh GMM supplemented with thiamine, THZ, or HMP for growth analysis. After 72 to 96 h of incubation with aeration, cell growth was measured as the OD600 (where 1 OD600 unit equals ∼1 × 109 CFU · ml−1). H. volcanii strains were grown by incubation at 42°C in 13- by 100-mm culture tubes. Cultures were aerated by rotary shaking (200 rpm). H. volcanii cultures were supplemented with novobiocin (0.1 mg per liter) for strains carrying pJAM plasmids. All growth assay experiments were performed at least in triplicate, and the means ± standard deviations (SD) were calculated.

Generation of H. volcanii mutant strains.

Manipulation of H. volcanii DNA and strains was performed as described in the Halohandbook (32). For the generation of the H. volcanii mutant strains, a pyrE2-based pop-in/pop-out deletion strategy was applied (33). In brief, predeletion plasmids were constructed by the ligation of the target gene and its 5′- and 3′-flanking regions (500 bp each) into the multiple-cloning sites of pyrE2-based plasmid pTA131. The resulting predeletion plasmids were subsequently used as a template to construct deletion plasmids by reverse PCR. Alternatively, deletion plasmids were also constructed by a one-step sequence- and ligation-independent cloning (SLIC) method (34). The 5′- and 3′-flanking regions (450 to 600 bp) were fused by recognizing the homologous 30 nt. The deletion plasmids were transformed into E. coli strain GM2163 to prevent the E. coli-mediated methylation of DNA and increase the efficiency of DNA transformation into H. volcanii. Strain fidelity was confirmed by PCR with primer pairs specific for the 5′- and 3′-flanking regions (700 bp each) of the target gene (that were not carried on the deletion plasmid) and genomic DNA as the template. The DNA sequence of the PCR products was determined by the UF ICBR DNA sequencing core using the Sanger DNA sequencing method.

Generation of H. volcanii expression plasmids and site-directed mutagenesis.

Target genes were isolated by PCR using gene-specific forward and reverse primers and H. volcanii genomic DNA that was extracted by the spooling method (32). The PCR products were ligated into the NdeI to KpnI sites of plasmid pJAM809, which carries the coding sequence for a C-terminal Strep-tag II tag that includes a GT linker (GTWSHPQPEK) and an rRNA P2 promoter to drive transcription. The resulting plasmids were used for the trans-expression of target genes in H. volcanii. Site-directed mutagenesis was performed according to Q5 site-directed mutagenesis kit (NEB) protocols. Appropriate plasmids were isolated from E. coli TOP10 and used as the template for PCR with SDM forward and reverse primer pairs. All constructed plasmids were verified by the UF ICBR DNA sequencing core using the Sanger DNA sequencing method.

SDS-PAGE and Western blotting.

H. volcanii strains were grown in 4 ml of GMM plus thiamine to stationary phase (OD600 of 0.8 to 1.0) (in 13- by 100-mm culture tubes) and harvested by centrifugation (8,600 × g for 2 min at room temperature). Cell pellets were boiled for 10 min in reducing SDS buffer (2% [wt/vol] SDS, 10% [vol/vol] glycerol, 5% [vol/vol] β-mercaptoethanol, 0.002% [wt/vol] bromophenol blue, and 62.5 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8]). Proteins were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto Hybond-P polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, Piscataway, NJ) at 4°C for 16 h at 30 V by tank blotting. Coomassie blue R-250 was used to compare equivalent protein loading. Strep-tag II-tagged proteins were detected by using a 1:5,000 dilution of an unconjugated rabbit anti-Strep-tag II polyclonal antibody (GenScript USA, Piscataway, NJ) and a 1:10,000 dilution of an alkaline phosphatase (AP)-linked goat anti-rabbit IgG(H+L) antibody (SouthernBiotech, Birmingham, AL) as primary and secondary antibodies, respectively. AP signals were detected by chemiluminescence with CDP-Star according to the supplier's protocols (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) and visualized with X-ray film (Hyperfilm; GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences).

β-Galactosidase reporter gene assay.

To analyze thiamine biosynthesis gene expression, promoter regions of target genes were fused by a PCR method (35) to bgaH, a β-galactosidase gene adapted from Haloferax alicantei (36). Control plasmids included pJAM2678, which carries bgaH downstream of the strong rRNA P2 promoter (P2rrnA) of Halobacterium cutirubrum, and pJAM2714, which is devoid of P2rrnA and the Shine-Dalgarno site. The promoter activity of each construct was monitored quantitatively by measuring β-galactosidase enzyme activity as previously described (37). In brief, cells were grown in 4 ml of GMM with and without thiamine supplementation and harvested at log phase (OD600 of 0.5 to 0.7) by centrifugation (8,600 × g for 2 min at 4°C). Cell pellets were washed two times with buffer A (50 mM Tris-Cl [pH 7.2], 2.5 M NaCl, and 10 μM MnCl2), resuspended in 300 μl of BgaH buffer (buffer A with 0.1% [wt/vol] β-mercaptoethanol), and lysed by using 100 μl of 0.1-mm glass beads (Chemglass Life Sciences, Vineland, NJ) (3 times total with 1 cycle of vortexing for 1 min at the highest speed with a Genie 2 vortexer [Fisher Scientific] and 2 min on ice). The cellular debris and glass beads were removed by centrifugation (8,600 × g for 2 min at 4°C). The total protein concentration of the cell extract was estimated by using the Bradford assay according to the supplier's protocols, with bovine serum albumin (BSA) as the standard (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). β-Galactosidase specific activity was measured for 30 min at 25°C in an assay mixture (100 μl) containing the cell extract (5 μg protein), BgaH buffer (up to 90 μl), and 10 μl of 2.66 mM o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (ONPG) solubilized in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer at pH 7.2. The liberation of o-nitrophenol from ONPG was monitored as the increase in the absorbance at 405 nm (A405) by using the kinetic mode of a Bio-Tek Synergy HT microtiter plate reader (Bio-Tek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT). Background values in which no substrate (ONPG) was added to the assay mixture were subtracted from the value for reaction mixtures containing the substrate for each lysate tested. All experiments were performed in biological triplicate, and the means ± SD of the results were calculated. One unit of β-galactosidase activity is defined as the amount of enzyme catalyzing the hydrolysis of 1 μmol ONPG · min−1 with a molar extinction coefficient for o-nitrophenol of 3,300 M−1 · cm−1.

Comparative genomics and structural modeling.

Protein sequences with homology to known enzymes of thiamine biosynthesis were retrieved from InterPro (38) and from GenBank by the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool using BLASTP (protein-protein BLAST) (39). Protein sequences were aligned by using ClustalW and imaged by using ESPript 3 (40). The intensive mode of the Phyre2 Web-based server (41, 42) was used for protein structural modeling of ThiN homologs. 3D protein structures and molecules were visualized and analyzed by using the interactive interface of Chimera 1.7 (43). UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot accession numbers were used to reference the protein sequences. A ThiR operator consensus sequence was identified upstream of thi4, thiC, and cytX homologs by using MEME suite v. 4.11.2 (44). DNA sequences 5′ of thi4, thiC, and thiE were input into the pipeline as follows: (i) motif discovery, (ii) discovered motifs (de novo), (iii) motif scanning by finding individual motif occurrences (FIMO), and (iv) annotated sequences.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank S. Shanker at the UF ICBR Genomics Core for Sanger DNA sequencing. Special thanks go to Dmitry Rodionov and colleagues for communication of their paper (45) prior to publication.

S.H. and J.A.M.-F. designed the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper; S.H., B.C., and M.A. performed the research; F.P. helped to draft the manuscript and performed bioinformatics analyses; and all authors read and approved of the paper.

Funds were awarded to J.A.M.-F. through the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Division of Chemical Sciences, Geosciences and Biosciences, Physical Biosciences Program (grant DE-FG02-05ER15650), and the National Institutes of Health (grant R01 GM57498). M.A. was awarded by the National Science Foundation's STEM Talent Expansion program.

We do not have a conflict of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.00810-16.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kowalska E, Kozik A. 2008. The genes and enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of thiamin and thiamin diphosphate in yeasts. Cell Mol Biol Lett 13:271–282. doi: 10.2478/s11658-007-0055-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jurgenson CT, Begley TP, Ealick SE. 2009. The structural and biochemical foundations of thiamin biosynthesis. Annu Rev Biochem 78:569–603. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.072407.102340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rentmeister A, Mayer G, Kuhn N, Famulok M. 2007. Conformational changes in the expression domain of the Escherichia coli thiM riboswitch. Nucleic Acids Res 35:3713–3722. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Croft MT, Moulin M, Webb ME, Smith AG. 2007. Thiamine biosynthesis in algae is regulated by riboswitches. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:20770–20775. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705786105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wachter A, Tunc-Ozdemir M, Grove BC, Green PJ, Shintani DK, Breaker RR. 2007. Riboswitch control of gene expression in plants by splicing and alternative 3′ end processing of mRNAs. Plant Cell 19:3437–3450. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.053645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Winkler W, Nahvi A, Breaker RR. 2002. Thiamine derivatives bind messenger RNAs directly to regulate bacterial gene expression. Nature 419:952–956. doi: 10.1038/nature01145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miranda-Ríos J. 2007. The THI-box riboswitch, or how RNA binds thiamin pyrophosphate. Structure 15:259–265. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sudarsan N, Barrick JE, Breaker RR. 2003. Metabolite-binding RNA domains are present in the genes of eukaryotes. RNA 9:644–647. doi: 10.1261/rna.5090103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheah MT, Wachter A, Sudarsan N, Breaker RR. 2007. Control of alternative RNA splicing and gene expression by eukaryotic riboswitches. Nature 447:497–500. doi: 10.1038/nature05769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nishimura H, Kawasaki Y, Kaneko Y, Nosaka K, Iwashima A. 1992. A positive regulatory gene, THI3, is required for thiamine metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Bacteriol 174:4701–4706. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.14.4701-4706.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nishimura H, Kawasaki Y, Kaneko Y, Nosaka K, Iwashima A. 1992. Cloning and characteristics of a positive regulatory gene, THI2 (PHO6), of thiamin biosynthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett 297:155–158. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80349-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hohmann S, Meacock PA. 1998. Thiamin metabolism and thiamin diphosphate-dependent enzymes in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae: genetic regulation. Biochim Biophys Acta 1385:201–219. doi: 10.1016/S0167-4838(98)00069-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harbison CT, Gordon DB, Lee TI, Rinaldi NJ, Macisaac KD, Danford TW, Hannett NM, Tagne JB, Reynolds DB, Yoo J, Jennings EG, Zeitlinger J, Pokholok DK, Kellis M, Rolfe PA, Takusagawa KT, Lander ES, Gifford DK, Fraenkel E, Young RA. 2004. Transcriptional regulatory code of a eukaryotic genome. Nature 431:99–104. doi: 10.1038/nature02800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nosaka K, Onozuka M, Konno H, Kawasaki Y, Nishimura H, Sano M, Akaji K. 2005. Genetic regulation mediated by thiamin pyrophosphate-binding motif in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Microbiol 58:467–479. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nosaka K, Esaki H, Onozuka M, Konno H, Hattori Y, Akaji K. 2012. Facilitated recruitment of Pdc2p, a yeast transcriptional activator, in response to thiamin starvation. FEMS Microbiol Lett 330:140–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2012.02543.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hwang S, Cordova B, Chavarria N, Elbanna D, McHugh S, Rojas J, Pfeiffer F, Maupin-Furlow JA. 2014. Conserved active site cysteine residue of archaeal THI4 homolog is essential for thiamine biosynthesis in Haloferax volcanii. BMC Microbiol 14:260. doi: 10.1186/s12866-014-0260-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eser BE, Zhang X, Chanani PK, Begley TP, Ealick SE. 2016. From suicide enzyme to catalyst: the iron-dependent sulfide transfer in Methanococcus jannaschii thiamin thiazole biosynthesis. J Am Chem Soc 138:3639–3642. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b00445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang X, Eser BE, Chanani PK, Begley TP, Ealick SE. 2016. Structural basis for iron-mediated sulfur transfer in archael [sic] and yeast thiazole synthases. Biochemistry 55:1826–1838. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.6b00030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hayashi M, Kobayashi K, Esaki H, Konno H, Akaji K, Tazuya K, Yamada K, Nakabayashi T, Nosaka K. 2014. Enzymatic and structural characterization of an archaeal thiamin phosphate synthase. Biochim Biophys Acta 1844:803–809. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2014.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brenneis M, Hering O, Lange C, Soppa J. 2007. Experimental characterization of cis-acting elements important for translation and transcription in halophilic archaea. PLoS Genet 3:e229. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Babski J, Haas KA, Näther-Schindler D, Pfeiffer F, Förstner KU, Hammelmann M, Hilker R, Becker A, Sharma CM, Marchfelder A, Soppa J. 2016. Genome-wide identification of transcriptional start sites in the haloarchaeon Haloferax volcanii based on differential RNA-Seq (dRNA-Seq). BMC Genomics 17:629. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-2920-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rodionov DA, Vitreschak AG, Mironov AA, Gelfand MS. 2002. Comparative genomics of thiamin biosynthesis in procaryotes. New genes and regulatory mechanisms. J Biol Chem 277:48949–48959. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208965200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luscombe NM, Austin SE, Berman HM, Thornton JM. 2000. An overview of the structures of protein-DNA complexes. Genome Biol 1:REVIEWS001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schumacher MA, Piro KM, Xu W. 2010. Insight into F plasmid DNA segregation revealed by structures of SopB and SopB-DNA complexes. Nucleic Acids Res 38:4514–4526. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beamer LJ, Pabo CO. 1992. Refined 1.8 Å crystal structure of the lambda repressor-operator complex. J Mol Biol 227:177–196. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90690-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stawiski EW, Gregoret LM, Mandel-Gutfreund Y. 2003. Annotating nucleic acid-binding function based on protein structure. J Mol Biol 326:1065–1079. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(03)00031-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones S, Shanahan HP, Berman HM, Thornton JM. 2003. Using electrostatic potentials to predict DNA-binding sites on DNA-binding proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 31:7189–7198. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morett E, Korbel JO, Rajan E, Saab-Rincon G, Olvera L, Olvera M, Schmidt S, Snel B, Bork P. 2003. Systematic discovery of analogous enzymes in thiamin biosynthesis. Nat Biotechnol 21:790–795. doi: 10.1038/nbt834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morett E, Saab-Rincón G, Olvera L, Olvera M, Flores H, Grande R. 2008. Sensitive genome-wide screen for low secondary enzymatic activities: the YjbQ family shows thiamin phosphate synthase activity. J Mol Biol 376:839–853. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dyda F, Furey W, Swaminathan S, Sax M, Farrenkopf B, Jordan F. 1993. Catalytic centers in the thiamin diphosphate dependent enzyme pyruvate decarboxylase at 2.4-Å resolution. Biochemistry 32:6165–6170. doi: 10.1021/bi00075a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Montange RK, Batey RT. 2008. Riboswitches: emerging themes in RNA structure and function. Annu Rev Biophys 37:117–133. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.37.032807.130000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dyall-Smith M. 2009. The Halohandbook: protocols for halobacterial genetics, version 7.2. http://www.haloarchaea.com/resources/halohandbook/Halohandbook_2009_v7.2mds.pdf.

- 33.Bitan-Banin G, Ortenberg R, Mevarech M. 2003. Development of a gene knockout system for the halophilic archaeon Haloferax volcanii by use of the pyrE gene. J Bacteriol 185:772–778. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.3.772-778.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jeong JY, Yim HS, Ryu JY, Lee HS, Lee JH, Seen DS, Kang SG. 2012. One-step sequence- and ligation-independent cloning as a rapid and versatile cloning method for functional genomics studies. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:5440–5443. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00844-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cha-Aim K, Hoshida H, Fukunaga T, Akada R. 2012. Fusion PCR via novel overlap sequences. Methods Mol Biol 852:97–110. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-564-0_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holmes ML, Dyall-Smith ML. 2000. Sequence and expression of a halobacterial β-galactosidase gene. Mol Microbiol 36:114–122. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rawls KS, Yacovone SK, Maupin-Furlow JA. 2010. GlpR represses fructose and glucose metabolic enzymes at the level of transcription in the haloarchaeon Haloferax volcanii. J Bacteriol 192:6251–6260. doi: 10.1128/JB.00827-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jones P, Binns D, Chang HY, Fraser M, Li W, McAnulla C, McWilliam H, Maslen J, Mitchell A, Nuka G, Pesseat S, Quinn AF, Sangrador-Vegas A, Scheremetjew M, Yong SY, Lopez R, Hunter S. 2014. InterProScan 5: genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics 30:1236–1240. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol 215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Robert X, Gouet P. 2014. Deciphering key features in protein structures with the new ENDscript server. Nucleic Acids Res 42:W320–W324. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kelley LA, Sternberg MJ. 2009. Protein structure prediction on the Web: a case study using the Phyre server. Nat Protoc 4:363–371. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bennett-Lovsey RM, Herbert AD, Sternberg MJ, Kelley LA. 2008. Exploring the extremes of sequence/structure space with ensemble fold recognition in the program Phyre. Proteins 70:611–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE. 2004. UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem 25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bailey TL, Johnson J, Grant CE, Noble WS. 2015. The MEME suite. Nucleic Acids Res 43:W39–W49. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rodionov DA, Leyn SA, Li X, Rodionova IA. 2017. A novel transcriptional regulator related to thiamine phosphate synthase controls thiamine metabolism genes in Archaea. J Bacteriol 199:e00743-16. doi: 10.1128/JB.00743-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.