To the Editor: Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs) taken for ≥1 year have been linked to increased fragility fracture (FF) risk, prompting the US FDA to issue a related warning. The oldest old (≥85) and patients with comorbidities may be at greater risk (1); however, little or no evidence has been available in these groups of vulnerable people. In this retrospective-matched cohort study with difference-in-difference methods, we investigated the 4-year FF risk in older patients (≥60) and patients with comorbidities.

We used the Clinical Practice Research Datalink, a database of primary care electronic medical records linked to hospital records. The sample included 86,469 patients receiving PPIs for ≥1 year and 86,469 age- and gender-matched controls, registered with a primary care practice in England between April 1997 and March 2014.

PPIs (esomeprazole, lansoprazole, omeprazole, pantoprazole, rabeprazole) were identified in the electronic prescribing data and analyzed as a class, regardless of dosage. The date of the first PPI prescription for the treated member of each matched pair was deemed the pair's index date.

FFs, were defined by hospitalization for new spine, hip, wrist, humerus, pelvis, ankle and rib fracture, coded using ICD-10. Patients with FFs within 3 months before their first PPI prescription were excluded, to avoid bias (2).

Cox's regressions were used to compare FF risk during the 4 years before (pre-treatment period) and after (treatment period) index date. According to the Prior Event Rate Ratio (PERR) approach (3), a difference-in-difference method, hazard ratios in the pre-treatment period were used to correct the treatment period hazard ratios. PERR was used to address both measured and unmeasured confounding, the latter being a major caveat in the interpretation of current evidence (4).

Results were stratified by age (60–74, 75–84, and ≥85) and comorbidity (Charlson comorbidity index, 0 and ≥1). Numbers needed to harm (NNHs) were also calculated (5). Subgroups were compared using confidence intervals since interactions cannot be tested using PERR.

The mean age was 71.9 (±7.9) years. FF rates in people aged ≥60 and those 60–74, 75–84, and ≥85 were 11.7, 7.3, 18.5, and 33 per 1000 person-years, respectively.

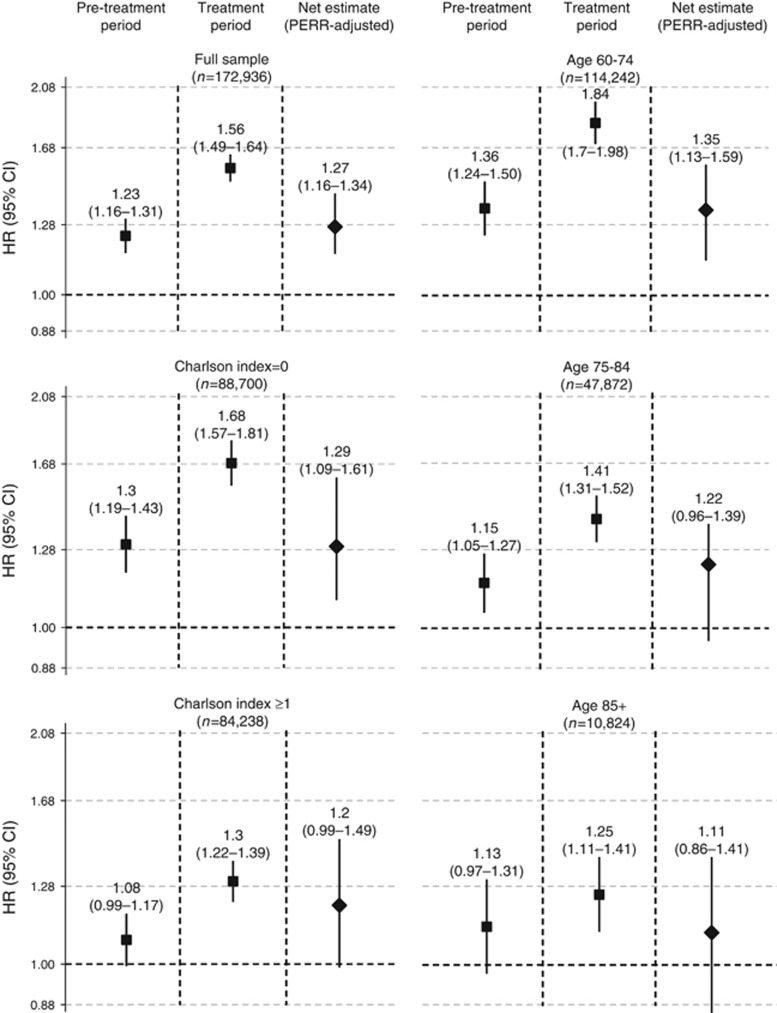

Differences at index date between treatment groups (Table 1) were reflected by higher hazard ratios in patients exposed to PPIs in both pretreatment and treatment periods (Figure 1). Measured and unmeasured confounding has been addressed using PERR.

Table 1. Percent of selected characteristics at index date.

| Characteristica | Controls N=86,469 | Treated N=86,469 |

|---|---|---|

| Age group | ||

| 60–74 | 66.1 | 66.1 |

| 75–84 | 27.7 | 27.7 |

| 85+ | 6.3 | 6.3 |

| Gender (women) | 56.4 | 56.4 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White | 60.2 | 79.9 |

| Non-white | 1.4 | 2.5 |

| Not recorded/Undisclosed | 38.5 | 17.5 |

| Poorer socio-economic status (3rd–5th quintile of index of multiple deprivation) | 50.3 | 52.2 |

| Body mass index | ||

| Underweight (<18.5 kg/m2) | 1 | 1 |

| Normal (18.5–24.9 kg/m2) | 17.3 | 18.4 |

| Overweight (25–29.9 kg/m2) | 20.4 | 25.8 |

| Obese (≥30 kg/m2) | 12.7 | 18.1 |

| Unrecorded | 48.5 | 36.8 |

| Smoking status | ||

| Never smokers | 44.6 | 41 |

| Ex-smokers | 17.6 | 21.9 |

| Current smokers | 28 | 32.6 |

| Not recorded | 9.8 | 4.4 |

| Alcohol drinking | ||

| Never/currently not | 9 | 10.6 |

| Current, known amount | 42.2 | 47.2 |

| Heavy | 9.4 | 12 |

| Current, unknown amount | 0.9 | 1 |

| Former | 2.2 | 3 |

| Undetermined | 36.4 | 26.2 |

| Charlson comorbidity index (≥1) | 39.8 | 57.6 |

| Falls (within a year before baseline) | 11.6 | 16.6 |

| Anaemia | 2.7 | 7.7 |

| Ischemic stroke | 5.5 | 9.3 |

| Coronary heart disease | 10.5 | 20.1 |

| Osteoporosis | 3.6 | 6 |

| Osteoarthritis | 19.9 | 32.6 |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease | 0.2 | 4.6 |

| Vitamin D supplement | 3.9 | 9 |

| Corticosteroids | 25.2 | 44.3 |

| Oestrogen | 2.2 | 4.4 |

| Testosterone | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Anti-thyroid drugs | 0.2 | 0.3 |

| Levothyroxine | 6 | 8.6 |

All differences (except for gender and age groups) between the PPI-treated and controls significant at P<0.001 (χ2).

Figure 1.

Hazard ratios for pre-treatment and treatment periods, and PERR-adjusted hazard ratios for the full sample and by comorbidity and age groups (log-scale). Confidence intervals for PERR analyses were calculated using bootstrapping techniques. 95%CI, 95% confidence interval; CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; HR, hazard ratio; HRPERR=HRTreatment period/HRPre-treatment period; PERR, Prior Event Rate Ratio.

In the adjusted analysis (net estimates, Figure 1) across the studied age-range, patients receiving PPIs were at greater risk of FF than controls (PERR-adjusted Hazard Ratio: 1.27: 95%CI: 1.16–1.34) after accounting for prior differences in FF rates. The Hazard Ratio for PPI use in those aged ≥85 overlapped with that in younger groups and were similar in patients with and without comorbidity. Sensitivity analyses excluding people with corticosteroids co-prescription and their matched pairs showed similar results (HR: 1.23, 95%CI: 1.05–1.44).

Since the hazard estimates were similar in age and comorbidity subgroups, subgroup-specific NNHs were calculated by applying the full-sample risk estimate to subgroup-specific FF rates (5). The NNH for FF in all patients aged ≥60 was 121 (95%CI: 81 to 222) over 4 years. NNH in patients ≥85 (45, 30 to 81) was lower than that in ages 60–74 (207, 141 to 368) but similar in patients with and without co-morbidity (data not shown).

This observational study, using a validated method to address unmeasured confounding, confirms an ~30% increased FF risk in older patients receiving PPIs for ≥1 year. Although there were similar excess risks in patients aged ≥85, given the higher absolute risk of FF in this group, only 45 patients need to be treated to harm one, suggesting that PPIs should be used with caution especially for symptomatic relief in this group. In the UK, the vast majority of people aged ≥60 receive free drug prescriptions and the ≥1 year over-the-counter PPI use is therefore limited and unlikely to bias our results.

Footnotes

Guarantor of the article: Alessandro Ble, MD.

Specific author contributions: Study concept and design, acquisition or interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, statistical analysis and approved the final draft: Jan Zirk-Sadowski; Study concept and design, acquisition or interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript and critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Jane A. Masoli; acquisition or interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final draft: David Strain; acquisition or interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final draft: Joao Delgado; acquisition or interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content statistical analysis and approved the final draft: William Henley; acquisition or interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final draft: Willy Hamilton; Study concept and design, acquisition or interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content statistical analysis and approved the final draft:David Melzer; Study concept and design, acquisition or interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, statistical analysis and approved the final draft: Alessandro Ble. Dr Zirk-Sadowski and Dr Ble had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Financial support: This research is funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), grant number: PB-PG-0214-3309. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the UK Department of Health.

Potential competing interests: Alessandro Ble is a former employee of Pfizer (until November 2012). The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Reimer C. Safety of long-term PPI therapy. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2013;27:443–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uddin MJ, Groenwold RH, van Staa TP et al. Performance of prior event rate ratio adjustment method in pharmacoepidemiology: a simulation study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2015;24:468–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brophy S, Jones KH, Rahman MA et al. Incidence of Campylobacter and Salmonella infections following first prescription for PPI: a cohort study using routine data. Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108:1094–1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laine L, Nagar A. Long-term ppi use: balancing potential harms and documented benefits. Am J Gastroenterol 2016;111:913–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barratt AL, Wyer PC, Guyatt G et al. NNT for studies with long-term follow-up. CMAJ 2005;172:613–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]