Abstract

Surveillance studies and outbreak investigations indicate that an extensively drug‐resistant (XDR) form of tuberculosis (TB) is increasing in prevalence worldwide. In outbreak settings among HIV‐infected, there is a high‐case fatality rate. Better outcomes occur in HIV‐uninfected, particularly if drug susceptibility test (DST) results are available rapidly to allow tailoring of drug therapy. This review will be presented in two segments. The first characterizes the problem posed by XDR‐TB, addressing the epidemiology and evolution of XDR‐TB and treatment outcomes. The second reviews technologic advances that may contribute to the solution, new diagnostics, and advances in understanding drug resistance and in the development of new drugs.

Keywords: tuberculosis, drug resistant tuberculosis, multidrug resistant tuberculosis, extensively drug resistant tuberculosis

Introduction

Extensively drug‐resistant tuberculosis (XDR‐TB) is an emerging global health problem that, as of June 2008, had been reported to the World Health Organization from 49 countries. It is increasing in incidence in the wake and because of the spread of multidrug‐resistant TB (MDR‐TB). XDR‐TB is difficult and very expensive to treat, and in many settings, may be incurable. Its emergence threatens to undermine advances in TB control. The best hope for the containment of XDR‐TB is improved TB control programs, infection control measures to avoid nosocomial outbreaks, the development and dissemination of technologies for rapid diagnosis of TB and determination of drug susceptibility of isolates of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M. tuberculosis), and the development of new drugs and vaccines.

The discovery of the first chemotherapeutic agents to treat TB was met with great expectations. Unfortunately, it led to a diminished interest in TB and resources for TB research and control. It was assumed that the public health problems posed by TB would dissipate with the availability of effective therapies. This proved short‐sighted for several reasons. First, treatment of TB with a single agent led to the rapid emergence of drug resistance. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 Second, multidrug treatment was effective but required administration for a prolonged period, at least 6 months. A failure of patients or of providers to assure completion of appropriate adherence to and completion of treatment led to relapse with organisms with acquired resistance. Both issues relate to the fact that M. tuberculosis shows a low level of spontaneous resistance to each of the drugs used to treat it. The number of organisms in a tuberculous cavity (1011/g) is sufficient to harbor organisms that are resistant to each of the individual drugs. 1 Treatment with only a single drug or with several drugs administered/taken erratically may select for replication of organisms harboring single or multidrug resistance. 5 Standard treatment of an unrecognized resistant organism also may lead to acquisition of additional resistance. Early studies suggested that drug‐resistant isolates were less virulent. 4 It is clear, now, that some drug‐resistant isolates are as virulent as drug‐sensitive isolates with regard to transmission of M. tuberculosis. There have been multiple outbreaks where transmission of drug‐resistant organisms has been documented. 6

MDR‐TB is defined as infection due to organisms resistant to at least the two first‐line drugs, isonazid (INH) and rifampin (RIF). Prior to the emergence of the HIV pandemic, MDR‐TB appeared to be more of a problem in indigent areas of the world with poor TB control programs. However, the HIV epidemic led to explosive nosocomial outbreaks of MDR‐TB, increasing awareness of what had been a smoldering global problem. In fact, the outbreaks of MDR‐TB led to use and misuse of second‐line drugs, a key factor in the current emergence of XDR‐TB.

Patients presenting with MDR‐TB usually can be cured. This, however, requires combinations of “second‐line drugs” that are less effective, more toxic, and more expensive (3‐ to 100‐fold depending on the country) than first‐line therapy and need to be administered for a longperiod (18–24 months). In most resource‐limited settings, second‐line drugs, in fact, are not available and patients with MDR‐TB remain infectious for a protracted period, if not throughout their lifetime, posing a grave public health risk.

When regimens containing second‐line drugs are selected or administered incorrectly, MDR‐TB isolates acquire additional drug resistance and become even more difficult or impossible to cure. XDR‐TB has been problematic for decades. It received the name and definition only recently. The current definition of XDR‐TB requires, that an isolate be MDR‐TB that is resistant to INH and RIF plus show additional resistance to a fiuoroquinolone and at least one of the three second‐line injectables (kanamycin, amikacin, and capreomycin). As with MDR‐TB, HIV infection has been an essential factor in promoting outbreaks of XDR‐TB that fanned concerns in the medical and public health community but also the media and the populace.

The first part of this review will consider the clinical and public health issues posed by MDR‐TB and XDR‐TB. The second section will examine developments in diagnostics, recent advances in understanding mechanisms of resistance, and new interventions.

Epidemiology of XDR‐TB

The estimates of global MDR‐TB have increased from 272,906 (95% CI 184,948–414,295) in 2000 to 424,203 (376,019–620,061) in 2002, representing 4.3% (95% CI 3.8–6.1%) of all TB cases. 7 The most recent data are from March 2008 and estimate 490,000 new cases of MDR‐TB emerging each year with 110,000 deaths. 8 If 5–10% of these represent XDR‐TB, there would be approximately 25,000–50,000 new cases per year, worldwide.

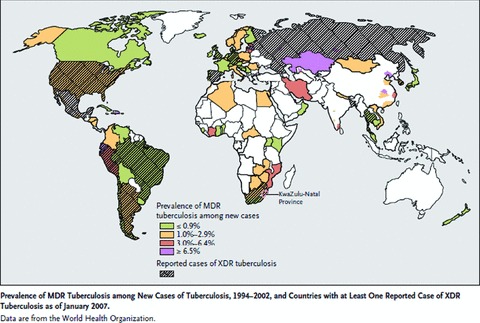

MDR‐TB is a global problem; there are “hot‐spots” for MDR‐TB, many of which are in Asia and the former Soviet Union, where large proportions of new TB cases are MDR ( Figure 1 ). 9 MDR‐TB has been less of an issue in Africa, in part, because of the delayed introduction of rifampin. It is of interest, therefore, that the current locus of concern regarding XDR‐TB is centered on South Africa. This is largely because of a well‐described nosocomial outbreak in South Africa and the likelihood that the spread of XDR‐TB in the population will be accelerated by the ongoing HIV epidemic. The overall impact of HIV on TB in Africa recently has been reviewed. 10

Figure 1.

Prevalence of MDR‐TB among new cases of TB, 1994–2002, and countries with at least one reported case of XDR‐TB as of January 2007. Data from World Health Organization. 9 Reprinted from Reference 9, with permission.

The initial report of a laboratory survey and provisional definition of XDR‐TB was published in November 2005. 11 This initial definition required the isolate to show resistance to at least three second‐line drugs. In March 2006, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization reported on the emergence of XDR‐TB worldwide. 12 In this survey of a network of international laboratories, of 17,690 isolate of M. tuberculosis, 20% were MDR‐TB and 2% were XDR‐TB. In the United States, 4% of MDR‐TB cases were XDR, in Latvia 19%, and in South Korea 15%. The case definition of XDR‐TB was revised to the current definition in October 2006. 3 By this definition, 49 cases of XDR‐TB occurred in the United States between 1993 and 2006. 13 In most countries, the proportion of MDR‐TB cases that fulfill the definition of XDR‐TB is in the range of 5–10%. For unknown reasons, a higher proportion (53%) of MDR isolates in Portugal appeared to be XDR‐TB. 14

Concurrent with the renewed concern about drug‐resistant TB, an epidemic of XDR‐TB was occurring in rural South Africa. 15 In a study of TB‐HIV integration, drug susceptibility testing (DST) of M. tuberculosis isolates indicated that 6 of 119 patients with MDR‐TB fulfilled the revised definition of XDR‐TB. After the initial finding of XDR‐TB among treatment nonresponsive patients, second‐line DST was initiated in all TB suspects in KwaZulu Natal and corresponding clinical data were obtained. This enhanced surveillance showed that of 1,539 patients studied from January 2005 to March 2006, 221 had MDR‐TB and 53 had XDR‐TB. Fifty‐two of the 53 patients with XDR‐TB died, a median of 16 days following the diagnosis. Genotyping showed that 85% of patients had genetically similar isolates belonging to the KZN strain family, implying person‐to‐person transmission. A total of 55% of patients with XDR‐TB had no previous treatment for TB, 67% had a recent hospital admission, and all of the 44 patients tested were HIV‐infected. The patients with XDR‐TB typically had no known family contact with active TB and there was no obvious community transmission pattern. This series of observations is remarkably similar to the nosocomial outbreaks of MDR‐TB that occurred in the 1990s in the United States. 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 Since the initial reports, a total of 239 XDR‐TB cases have been found in Tugela Ferry. 25

The nature of the interaction between HIV and MDR/XDR‐TB is the key to understanding the spread of drug‐resistant TB. When a patient with TB is hospitalized, the initial treatment regimens will abort transmission if the isolate is fully susceptible to first‐line agents. However, the TB patient with MDR‐ or XDR‐TB will remain infectious for prolonged periods. HIV‐infected hosts on the ward have enormous susceptibility to TB. Once they are infected with M. tuberculosis, disease will develop rapidly. For example, in a study by Daley and coworkers, 40% of all HIV‐infected individuals exposed to a case of infectious pulmonary TB in a residential facility themselves developed TB disease within 120 days. 23 In this outbreak, many of the secondary cases also were acid‐fast bacilli (AFB) sputum smear‐positive and, therefore, highly infectious. This provides the potential for an exponential increase in the number of cases that are transmitting infection and an explosive outbreak. This is dramatically different from traditional TB outbreaks in which the index case infects close contacts but few (<5%) develop disease and do so only over a course of months to years. HIV‐infected do not have a particular susceptibility to infection with drug‐resistant as compared to drug‐susceptible M. tuberculosis; 26 , 27 , 28 their susceptibility resides in the progression from infection to disease.

There also is evidence of an increasing number of cases of XDR‐TB in South Africa, 29 where XDR‐TB has been detected in over 40 healthcare facilities, in every province and among persons without HIV infections.

While problematic, outbreaks are not the main source of new cases of XDR‐TB. In most patients with XDR‐TB, resistance has been acquired in a stepwise manner by repeated episodes of TB that are not treated effectively. A study from Korea assessed XDR‐TB in a prospective observational cohort of TB patients at a referral hospital. 30 Previous duration of treatment with second‐line drugs was a significant predictor of XDR‐TB; a cumulative treatment duration of 18–34 months (as compared to ≤8 months) was associated with a 5.8‐fold greater risk of XDR‐TB. The number of second‐line drugs used in prior treatment also was associated with an increased risk for XDR‐TB.

Microepidemics of XDR‐TB also occur in the community. 31 In a surveillance of drug resistance in Iran conducted in isolates collected between 2005 and 2005, 12 (10.9%) of 113 MDR‐TB strains had extensive drug resistance. All cases belonged to one of two household epidemiologic clusters. There also is evidence that 15 cases of XDR‐TB occurring in Norway over the course of 10 years were caused by a single strain traced to a patient that was lost to follow‐up. 32

In low TB incidence countries, most TB cases occur in the foreign‐born. 33 Not surprisingly, XDR‐TB also often occurs in the foreign‐born. Foreign‐born accounted for all cases of XDR‐TB in Germany (3 of 3) and 50% of cases in Italy (4 of 8) for 2003–2006. In California, in 1993–2006, 18 XDR‐TB cases were diagnosed. 34 Eighty‐three percent were in foreign‐born (most from Mexico) and 43% occurred within 6 months of immigration to the United States.

Evolution of XDR‐TB

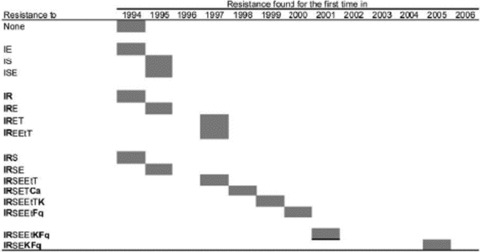

Serial genotyping of isolates of M. tuberculosis allows a current look at the concept that XDR‐TB evolves in a series of stages characterized by selection and propagation of isolates expressing unlinked spontaneous mutations and progressively increasing drug resistance. The main XDR‐TB strain responsible for the outbreak in KwaZulu Natal was F15/LAM4/KZN. Sequential studies indicate that the strain accounted for a number of cases of MDR‐TB in 1994, the first year in which isolates were accessible for study. 35 Resistance to as many as seven other drugs occurred, stepwise, in one decade ( Figure 2 ). The first XDR‐TB isolate was reported in 2001. In the absence of DST at the start of therapy, patients with MDR‐TB were treated with a standard four‐drug regimen (isonazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol) for the initial 2 months. This promoted emergence of resistance to ethambutol and pyrazinamide (as the causative organism was already resistant to at least isoniazid and rifampin). The “DOTS‐Plus” strategy was adopted by South Africa in 2001. This dictates the use of an empirical regimen in known cases of MDR‐TB. Additional susceptibility testing for second‐line drugs is not part of the strategy. Unfortunately, this appeared to have been a factor in the emergence of additional drug resistance.

Figure 2.

Development of drug resistance in the KwaZulu‐Natal family of strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis during the period 1994–2006. Ca = capreomycin, E = ethambutol, Et = ethionamide, F = fluoroquinolones, I = isoniazid, K = kanamycin/amikacin, R = rifampicin, S = streptomycin, T = thiacetazone. Reprinted from Reference 35, with permission.

For example, in Peru, 83% of MDR‐TB patients who failed treatment with an empirical regimen acquired additional drug resistance. 36

It is quite clear, therefore, that certain current practices promote development of XDR‐TB. One is the use of a four‐drug empirical regimen pending the results of DST or as is the usual case without access to DST. This may allow a TB patient with a drug‐resistant isolate to develop resistance to additional first‐line drugs. The second is the DOTS‐Plus program itself. Certainly, the emergence of drug resistance has provided the impetus to the development of greater capacity for and new approaches to DST.

In addition to clinical, public health, and biomedical issues, the spread of XDR‐TB raises ethical and programmatic implications such as involuntary confinement. These have been discussed elsewhere. 8 , 29 , 32

Treatment Outcomes

The initial reports suggested that the treatment outcomes in outbreaks of XDR‐TB in HIV‐infected patients were dire, with nearly uniform and rapid fatality. Subsequent reports based, in large part, on HIV‐uninfected TB patients who acquired XDR‐TB during prior cycles of treatment indicate that the outlook for them was poorer than for patients with MDR‐TB. However, a recent report from Peru indicates that with optimal management, outcomes of XDR‐TB in HIV‐uninfected may, in fact, be comparable to those of MDR‐TB.

As noted, in the initial report of the Tugela Ferry outbreak, 98% of patients died, all within 16 weeks of diagnosis of TB. This was essentially an outbreak in HI V‐infected persons. With recognition of the outbreak and consequent changes in management, outcomes have improved somewhat. Between June 2005 and March 2007, an additional 217 cases of XDR‐TB were diagnosed at Tugela Ferry with a case fatality rate of 84%. 25 More recently, at King George V Hospital in Durban, two‐thirds of the 133 patients diagnosed with XDR‐TB in 2007 still are alive. 25 , 29

There are published reports of an outbreak in Spain that in retrospect was due to anXDRM. bovis resistant to 11 drugs. 20 , 37 , 38 The combination of extremely drug‐resistant organism and HIV‐infected population resulted in nearly 100% fatality in less then 2 months. There also was evidence or re‐infection with M. bovis in patients initially hospitalized with drug‐susceptible M. tuberculosis. 39 Implementation of infection control measures ultimately controlled the outbreak. 38

Recent reports address the treatment of XDR‐TB in nonoutbreak settings and where HIV infection is not a comorbidity. 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 The results are quite variable, no doubt due to the differences in severity of illness, rapidity of diagnosis, access to second‐line drugs, local expertise in TB treatment, adherence to therapy, sample size, issues related to referral bias, and, perhaps most importantly, the extent of drug resistance. In general, however, XDR‐TB was associated with poorer treatment outcomes, longer periods of infectiousness, and higher case fatality rates than MDR‐TB. There was some evidence that surgical resection was associated with improved outcome.

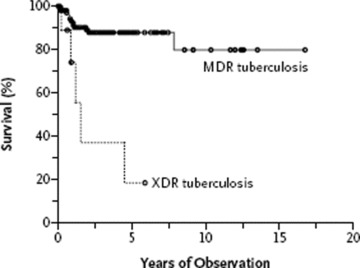

A typical series, recently published, was from a retrospective review of 205 patients referred to National Jewish Medical and Research Center and previously reported as having MDR‐TB; 6% (10 patients) could be classified as XDR‐TB. 46 As a group, patients with XDR‐TB showed poorer short‐ and long‐term outcomes and shortened survival compared to those with MDR‐TB ( Figure 3 ).

Figure 3.

Survival rates among patients with multidrug‐resistant TB and those with extensively drug‐resistant TB. Retrospective study of 164 patients with MDR‐TB and 10 patients with XDR‐TB treated at National Jewish Medical and Research Center. Kaplan–Meier survival curves estimates are based on the number of deaths from TB or surgery (p < 0.001 by the log‐rank test for the comparison of the two groups). The circles indicate the times of censoring. Reprinted from Reference 46, with permission.

The most promising and recent results come from a study in Peru that assessed comprehensive treatment of XDR‐TB (individualized therapy, resective surgery as indicated, adverse event management, and nutritional and psychological support). Treatment and services were provided to 48 patients with XDR‐TB in Lima between 1999 and 2002. 47 All patients who had failed previous treatment or had relapsed were placed initially on a five‐drug regimen including a fluoroquinolone and an injectable, pending the results of DST. Once susceptibilities were known, regimens were reinforced, if necessary, with known effective drugs and the injectable was continued for as long as 15 months. The drug regimen was continued for a median of 24.9 months, and a few patients were referred for surgery. The supervision of treatment was strict and had the requisite elements of support as well as intensive clinical and bacteriologic monitoring.

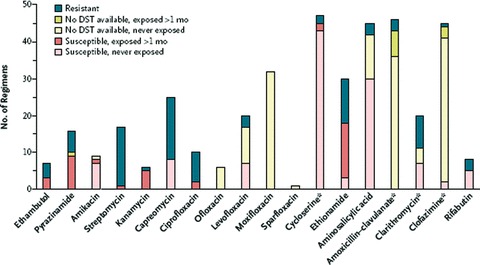

As compared to patients with MDR‐TB, the XDR patients had undergone more TB treatment (4.2 vs. 3.2 courses) and had isolates that were resistant to more drugs (8.4 vs. 5.3 drugs). The XDR‐TB patients received daily supervised therapy with an average of 5.3 drugs including cycoserine, an injectable, and a fluoroquinolone. Moxifloxacin and levofloxacin were commonly used even when the isolates were resistant to ciprofloxacin. The regimens relied heavily on three drugs, with little prior use in Peru, capreomycin, cycloserine, and para‐aminosacilic acid (PAS) ( Figure 4 ). Resective surgery was indicated for patients with high‐grade resistance, relatively localized disease, and lack of initial response, even in patients with restricted lung volumes. Healthcare workers assured a high level of treatment adherence and control of adverse events, and other obstacles to adherence were managed aggressively by nurses and physicians. A total of 60.4% of patients with XDR‐TB completed treatment or were cured as compared to 66.3% of patients with MDR‐TB (p= 0.36). The median time to culture conversion was 90 days in XDR‐TB, which was significantly longer than 61 days in MDR‐TB. Treatment duration was 26 months and case fatality rate was 22.9%, both comparable to outcomes in MDR‐TB. The cure rates in Peruvian study are particularly noteworthy as they exceed those in the United States and Europe. There may be differences, however, in the severity of illness, extent of drug resistance, selection of treatment regimens, and supervision of treatment‐patient support/adherence. The accompanying editorial to the publication of this study addresses systematic biases that may have led to robust results of treatment in this retrospective study. 48

Figure 4.

Use of anti‐TB agents in 48 individualized treatment regimens for XDR TB, drug‐susceptibility testing, and prior exposure to a particular agent in Lima, Peru (reprinted from Reference 50, with permission). Some susceptibility testing was performed for these agents. The asterisks indicate that some testing was performed for these agents. However, because of the relative infrequency of testing, as well as the lack of standardization or confirmed clinical relevance of tests for these drugs, clinicians relied less on these results than on those for other drugs. Reprinted from Reference 47, with permission.

The issue of fluoroquinolone resistance is a critical issue for treatment of MDR‐TB, 41 , 49 and presumably one of the reasons for a poorer outcome in XDR‐TB. Significantly, the rates of fluoroquinolone resistance appear to be quite variable—high in Korea, even among patients without XDR‐TB with their first diagnosis of TB and may be due to the over‐the‐counter use of fluoroquinolones. 30 For unclear reasons, this high rate of fluoroquinolone resistance is not seen in Latvia, 41 or in prisoners in Georgia, 50 or in our study in Uganda. 51 In Georgia, despite high levels of resistance to at least three second‐line anti‐TB drugs, patients were not defined as having XDR‐TB because of the low rate of resistance to fluoroquinolones (2.2% XDR‐TB among 59 patients with MDR‐TB). Some patients with isolates resistant to ciprofloxacin have been treated with newer fluoroquinolones such as moxifloxacin.

The role of injectables in response to therapy also has been assessed in a series of TB patients from Estonia, Germany, Italy, and the Russian Federation between 1999 and 2006. 52 Among 240 MDR‐ and 48 XDR‐TB cases, resistance to capreomycin was independently associated with unfavorable outcome (odds ratio 3.51). Susceptibility to kanamycin and amikacin did not influence the outcome. These data confirm and extend studies of the outcome of treatment of MDR‐TB in New York City. 53 Among 221 HIV‐infected patients in New York City infected with the highly resistant “W” strain of M. tuberculosis, treatment with capreomycin or with a fluoroquinolone for at least 12 weeks was a predictor of survival. The strongest predictor was treatment with capreomycin (adjusted odds ratio of 7.3), which was an even stronger predictor than CD4 count.

There is a group of drugs approved for indications other than TB that have in vitro activity against M. tuberculosis. These drugs have been used in multidrug “salvage” regimens to treat the most resistant cases of XDR‐TB. For example, in the recent publication reporting successful treatment of MDR‐TB in Peru, 47 a substantial number of regimens included amoxicillin‐clavulanate, clarithromycin, or clofazamine ( Figure 4 ). It is impossible to assess the contributions of these drugs to treatment outcome. A recent case series reported the results of treatment with linezolid, an oral oxazolidinone antibiotic in seven refractory cases of XDR‐TB. 54 The salvage regimen produced sputum conversion (mean 53 days) and radiographic and clinical improvement in all. Three patients developed neutropenia and two developed peripheral neuropathy. Others have reported higher rates of dose‐limiting toxicities in the treatment of MDR‐TB. 55

References

- 1. Canetti GJ. Changes in tuberculosis as seen by a pathologist. Am Rev Tuberc. 1959; 79(5): 684–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fox W, Wiener A, Mitchison DA, Selkon JB, Sutherland I. The prevalence of drug‐resistant tubercle bacilli in untreated patients with pulmonary tuberculosis: a national survey, 1955–56. Tubercle. 1957; 38(2): 71–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mitchison DA. Development of streptomycin resistant strains of tubercle bacilli in pulmonary tuberculosis: results of simultaneous sensitivity tests in liquid and on solid media. Thorax. 1950; 5(2): 144–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mitchison DA. Tubercle bacilli resistant to isoniazid; virulence and response to treatment with isoniazid in guinea‐pigs. BMJ. 1954; 1(4854): 128–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Iseman MD. Extensively drug‐resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis: Charles Darwin would understand. Clin Infect Dis. 2007; 45(11): 1415–1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Teixeira L, Perkins MD, Johnson JL, et al Infection and disease among household contacts of patients with multidrug‐resistant tuberculosis. IntJ Tuberc Lung Dis. 2001; 5(4): 321–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zignol M, Hosseini MS, Wright A, Lambregts‐van Weezenbeek C, Nunn P, Watt A, William BG, Dye C. Global incidence of multidrug‐resistant tuberculosis. J Infect Dis. 2006; 194(4): 479–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Singh JA, Upshur R, Padayatchi N. XDR‐TB in South Africa: no time for denial or complacency. PLoSMed. 2007; 4(1): e50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Raviglione MC, Smith IM. XDR tuberculosis—implications for global public health. N Engl J Med. 2007; 356(7): 656–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chaisson RE, Martinson NA. Tuberculosis in Africa—combating an HIV‐driven crisis. N Engl J Med. 2008; 358(11): 1089–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shah N, Wright A, Drobniewski F. Extreme drug resistance in tuberculosis (“XDR‐TB”): globa survey of supranational reference laboratories for Mycobacterium tuberculosis with resistance to second line drugs. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2005; 9(Suppl 1): S77. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Emergence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis with extensive drug resistance to second‐line drugs‐wordwide, 2000–2004. MMWR Morb Mort WklyRep. 2006; 55(11): 301–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Extensively drug resistant TB (XDR‐TB): recommendations for prevention and control. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2006; 81: 430–432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Perdigao J, Macedo R, Joao I, Fernandes E, Brum L, Portugal I. Multidrug‐resistant tuberculosis in Lisbon, Portugal: a molecular epidemiological perspective. Microb Drug Resist. 2008; 14(2) 133–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gandhi NR, Moll A, Sturm AW, Pawinski R, Govender T, Lalloo U, Zeller K, Andrews J, Friedland G. Extensively drug‐resistant tuberculosis as a cause of death in patients co‐infected with tuberculosis and HIV in a rural area of South Africa. Lancet. 2006; 368(9547): 1575–1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Frieden TR, Sterling T, Pablos‐Mendez A, Kilburn JO, Cauthen GM, Dooley SW. The emergence of drug‐resistant tuberculosis in New York City. N Engl J Med. 1993; 328(8): 521–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hannan MM, Peres H, Maltez F, Hayward AC, Machado J, Morgado A, Proenca R, Nelson MR, Bico J, Young DB, Gazzard BS. Investigation and control of a large outbreak of multi‐drug resistant tuberculosis at a central Lisbon hospital. J Hosp Infect. 2001; 47(2): 91–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Punnotok J, Shaffer N, Naiwatanakul T, Pumprueg U, Subhannachart P, Ittiravivongs A, Chuchotthaworn C, Ponglertnapagorn P, Chantharojwong N, Young NL, Limpakarnjanarat K, Mastro TD. Human immunodeficiency virus‐related tuberculosis and primary drug resistance in Bangkok, Thailand. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2000; 4(6): 537–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ritacco V, Di Lonardo M, Reniero A, et al Nosocomial spread of human immunodeficiency virus‐related multidrug‐resistant tuberculosis in Buenos Aires. J Infect Dis. 1997; 176(3): 637–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rullan JV, Herrera D, Cano R, Moreno V, Godoy P, Peiro EF, Castell J, Ibanez C, Ortega A, Agudo LS, Pozo F. Nosocomial transmission of multidrug‐resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Spain. Emerg Infect Dis. 1996; 2(2): 125–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sacks LV, Pendle S, Orlovic D, Blumberg L, Constantinou C. A comparison of outbreak‐ and nonoutbreak‐related multidrug‐resistant tuberculosis among human immunodeficiency virus‐infected patients in a South African hospital. Clin Infect Dis. 1999; 29(1): 96–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Campos PE, Suarez PG, Sanchez J, et al Multidrug‐resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis in HIV‐infected persons, Peru. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003; 9(12): 1571–1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Daley CL, Small PM, Schecter GF, Schoolnik GK, McAdam RA, Jacobs WR, Hopewell PC. An outbreak of tuberculosis with accelerated progression among persons infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. An analysis using restriction‐fragment‐length polymorphisms. N Engl J Med. 1992; 326(4): 231–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Joseph P, Severe P, Ferdinand S, Goh KS, Sola C, Haas DW, Johnson WD, Rastogi N, Pape JW, Fitzgerald DW. Multidrug‐resistant tuberculosis at an HIV testing center in Haiti. AIDS. 2006; 20(3): 415–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Koenig R. Drug‐resistant tuberculosis. In South Africa, XDR TB and HIV prove a deadly combination. Science. 2008; 319(5865): 894–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kenyon TA, Mwasekaga MJ, Huebner R, Rumisha D, Binkin N, Maganu E. Low levels of drug resistance amidst rapidly increasing tuberculosis and human immunodeficiency virus co‐epidemics in Botswana. IntJ Tuberc Lung Dis. 1999; 3(1): 4–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Churchyard GJ, Corbett EL, Kleinschmidt I, Mulder D, De Cock KM. Drug‐resistant tuberculosis in South African gold miners: incidence and associated factors. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2000; 4(5): 433–440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wilkinson D, Pillay M, Davies GR, Sturm AW. Resistance to antituberculosis drugs in rura South Africa: rates, patterns, risks, and transmission dynamics. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1996; 90(6): 692–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Andrews JR, Shah NS, Gandhi N, Moll T, Friedland G. Multidrug‐resistant and extensively drug‐resistant tuberculosis: implications for the HIV epidemic and antiretroviral therapy rollout in South Africa. J Infect Dis. 2007; 196(Suppl 3): S482‐S490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jeon CY, Hwang SH, Min JH, Prevots DR, Goldfeder LC, Lee H, Eum SY, Jeon DS, Kang HS, Kim JH, Kim BJ, Kim DY, Holland SM, Park SK, Cho SN, Barry CE 3rd, Via LE. Extensively drug‐resistant tuberculosis in South Korea: risk factors and treatment outcomes among patients at a tertiary referral hospital. Clin Infect Dis. 2008; 46(1): 42–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Masjedi MR, Farnia P, Sorooch S, et al Extensively drug‐resistant tuberculosis: 2 years of surveillance in Iran. Clin Infect Dis. 2006; 43(7): 841–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dahle UR. Extensively drug resistant tuberculosis: beware patients lost to follow‐up. BMJ 2006; 333(7570): 705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dahle UR, Eldholm V, Winje BA, Mannsaker T, Heldal E. Impact of immigration on the molecular epidemiology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in a low‐incidence country. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007; 176(9): 930–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Banerjee R, Allen J, Westenhouse J, Oh P, Elms W, Desmond E, Nitta A, Royce S, Flood J. Extensively drug‐resistant tuberculosis in California, 1993–2006. Clin Infect Dis. 2008; 47(4): 450–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pillay M, Sturm AW. Evolution of the extensively drug‐resistant F15/LAM4/KZN strain of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in KwaZulu‐Natal, South Africa. Clin Infect Dis. 2007; 45(11) 1409–1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Han LL, Sloutsky A, Canales R, Naroditskaya V, Shin SS, Seung KJ, Timperi R, Becerra MC. Acquisition of drug resistance in multidrug‐resistant/Wyco/pacfe/vum tuberculosis during directly observed empiric retreatment with standardized regimens. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2005; 9(7): 818–821. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Samper S, Martin C. Spread of extensively drug resistant tuberculosis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007; 13(4): 647–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Guerrero A, Cobo J, Fortun J, et al Nosocomial transmission of Mycobacterium bovis resistant to 11 drugs in people with advanced HIV‐1 infection. Lancet. 1997; 350(9093): 1738–1742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rivero A, Marquez M, Santos J, Pinedo A, Sanchez MA, Esteve A, Samper S, Martin C. High rate of tuberculosis reinfection during a nosocomial outbreak of multi‐drug resistant tuberculosis caused by Mycobacterium bovis strain B. Clin Infect Dis. 2001; 32: 159–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Migliori GB, Lange C, Centis R, Sotgiu G, Mutterlein R, Hoffmann H, Kliiman K, De laco G, Lauria FN, Richardson MD, Spanevello A, Cirillo DM, TBNET Study Group . Resistance to second‐line injectables and treatment outcomes in multidrug‐resistant and extensively drug‐resistant tuberculosis cases. Eur Respir J. 2008; 31(6): 1155–1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Leimane V, Riekstina V, Holtz TH, Zarovska E, Skripconoka V, Thorpe L, Laserson K, Wells C. Clinical outcome of individualised treatment of multidrug‐resistant tuberculosis in Latvia: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2005; 365(9456): 318–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kwon YS, Kim YH, Suh GY, Ching MP, Kim H, Kwon OJ, Choi YS, Kim K, Kim J, Shim YM, Koh WJ. Treatment outcomes for HIV‐uninfected patients with multidrug‐resistant and extensively drug‐resistant tuberculosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2008; 47(4): 496–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kim HR, Hwang SS, Kim HJ, Lee SM, Yoo CG, Kim YW, Han SK, Shim YS, Yim JJ. Impact of extensive drug resistance on treatment outcomes in non‐HIV‐infected patients with multidrug‐resistant tuberculosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2007; 45(10): 1290–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kim DH, Kim HJ, Park SK, Kong SJ, Kim YS, Kim TH, Kim EK, Lee KM, Lee SS, Park JS, Koh WJ, Lee CH, Kim JY, Shim TS. Treatment outcomes and long‐term survival in patients with extensively drug‐resistant tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bonilla CA, Crossa A, Jave HO, Mitnick CD, Jamanca RB, Herrera C, Asencios L, Mendoza A, Bayona J, Zignol M, Jaramillo E. Management of extensively drug‐resistant tuberculosis in Peru: cure is possible. PLoS ONE. 2008; 3(8): e2957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chan ED, Strand MJ, Iseman MD. Treatment outcomes in extensively resistant tuberculosis. N EnglJMed. 2008; 359(6): 657–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mitnick CD, Shin SS, Seung KJ, Rich ML, Atwood SS, Furin JJ, Fitzmaurice GM, Alcantara Vim FA, Appleton SC, Bayona JN, Bonilla CA, Chalco K, Choi S, Franke MF, Fraser HSF, Guerra D, Hurtado RM, Jazayeri D, Joseph K, Llaro K, Mestanza L, Mukherjee JS, Munoz M, Palacios E, Sanchez E, Sloutsky A, Becerra MC. Comprehensive treatment of extensively drug‐resistant tuberculosis. N Engl J Med. 2008; 359(6): 563–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Raviglione MC. Facing extensively drug‐resistant tuberculosis—a hope and a challenge. N Engl J Med. 2008; 359(6): 636–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Chan ED, Laurel V, Strand MJ, Chan JF, Huynh MN, Goble M, Iseman MD. Treatment and outcome analysis of 205 patients with multidrug‐resistant tuberculosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004; 169(10): 1103–1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Jugheli L, Rigouts L, Shamputa IC, Bram de Rijk W, Portaels F. High levels of resistance to second‐line anti‐tuberculosis drugs among prisoners with pulmonary tuberculosis in Georgia. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2008; 12(5): 561–566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Temple B, Ayakaka I, Ogwang S, Nabanjja H, Kayes S, Nakubulwa S, Worodria W, Levin J, Joloba M, Okwera A, Eisenach KD, McNerney R, Elliott AM, Smith PG, Mugerwa RD, Ellner JJ, Jones‐Lopez, EC . Rate and amplification of drug resistance in previously‐treated tuberculosis patients in Kampala, Uganda. Clin infect Dis. 2008; 47: 1126–1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Migliori GB, Lange C, Centis R, Sotgiu G, Mutterlein R, Hoffmann H, Kliiman K, De laco G, Lauria FN, Richardson MD, Spanevello A, Cirillo DM, and TBNET Study Group . Resistance to second‐line injectables and treatment outcomes in multidrug‐resistant and extensively drug‐resistant tuberculosis cases. Eur Respir J. 2008; 31(6): 1155–1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Frieden TR, Munsiff SS, Ahuja SD. Outcomes of multidrug‐resistant tuberculosis treatment in HIV‐positive patients in New York City, 1990–1997. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2007; 11(1): 116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Condos R, Hadgiangelis N, Leibert E, Jacquette G, Harkin J, Rom WN. Case series report of a linezolid‐containing regimen for extensively drug‐resistant tuberculosis. Chest. 2008; 134(1): 187–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Von Der Lippe B, Sandven P, Brubakk O. Efficacy and safety of linezolid in multidrug resistant tuberculosis (MDR‐TB)‐a report of ten cases. J Infect. 2006; 52(2): 92–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]