Abstract

There has been some debate about the disease-invoking potential of Staphylococcus aureus strains and whether invasive disease is associated with particularly virulent genotypes, or “superbugs.” A study in this issue of the JCI describes the genotyping of a large collection of nonclinical, commensal S. aureus strains from healthy individuals in a Dutch population. Extensive study of their genetic relatedness by amplified restriction fragment typing and comparison with strains that are associated with different types of infections revealed that the S. aureus population is clonal and that some strains have enhanced virulence. This is discussed in the context of growing interest in the mechanisms of bacterial colonization, antibiotic resistance, and novel vaccines.

Nasal colonization

Staphylococcus aureus is a common commensal of humans and its primary habitat is the moist squamous epithelium of the anterior nares (1). About 20% of the population are always colonized with S. aureus, 60% are intermittent carriers, and 20% never carry the organism. As there is considerable evidence that carriage is an important risk factor for invasive infection (1, 2), it is surprising that so little is known about the bacterial factors that promote colonization of squamous epithelial surfaces and the host factors that determine whether an individual can be colonized or not.

Methicillin-resistant S. aureus

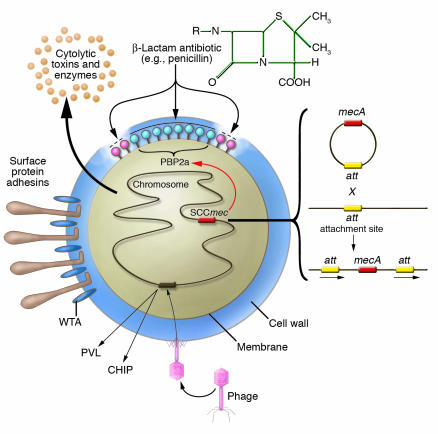

Healthy individuals have a small but finite risk of contracting an invasive infection caused by S. aureus, and this risk is increased among carriers. Hospital patients who are catheterized or who have been treated surgically have a significantly higher rate of infection. In some, but not all, developed countries, many nosocomial infections are caused by S. aureus strains that are multiply resistant to antibiotics — known as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) (3, 4) — although the acronym MRSA is somewhat misleading because the semisynthetic β-lactam methicillin is no longer used to treat S. aureus infections. In MRSA, the horizontally acquired mecA gene encodes a penicillin-binding protein, PBP2a, which is intrinsically insensitive to methicillin and all β-lactams that have been developed, including the isoxazoyl penicillins (e.g., oxacillin) that superceded methicillin, in addition to the broad spectrum β-lactams (third-generation cephalosporins, cefamycins, and carbapenems) that were introduced primarily to treat infections caused by Gram-negative bacteria (4) (Figure 1). In contrast to nosocomial MRSA strains, which are usually multidrug resistant, the recently emerged community-acquired MRSA (CA-MRSA) strains are susceptible to drugs other than β-lactams (5).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram illustrating how S. aureus acquires resistance to methicillin and its ability to express different virulence factors. The bacterium expresses surface protein adhesins and WTA and also secretes many toxins and enzymes by activation of chromosomal genes. Adhesins and WTA have been implicated in nasal and skin colonization. Resistance to methicillin is acquired by insertion of a horizontally transferred DNA element called SCCmec. Five different SCCmec elements can integrate at the same site in the chromosome by a Campbell-type mechanism involving site-specific recombination. The mecA gene encodes a novel β-lactam–insensitive penicillin binding protein, PBP2a, which continues to synthesize new cell wall peptidoglycan even when the normal penicillin binding proteins are inhibited. Some virulence factors such as PVL and the chemotaxis inhibitory protein, CHIP, are encoded by genes located on lysogenic bacteriophages.

The term MRSA is synonymous with multidrug-resistant S. aureus because many nosocomial MRSA strains are resistant to most commonly used antibiotics. The glycopeptide vancomycin was the last available drug to which this organism had remained uniformly sensitive until recent reports of low-level glycopeptide resistance (6) and, very recently, the transfer of high-level vancomycin resistance from Enterococcus to S. aureus (7). Although new drugs, including linezolid and synercid, have recently been introduced to treat MRSA infections (8), there is a worrying lack of novel drugs in the pipeline.

Virulence factors

S. aureus strains can express a wide array of potential virulence factors (Figure 1), including surface proteins that promote adherence to damaged tissue (9), bind proteins in blood to help evade antibody-mediated immune responses (9), and promote iron uptake (10). The organism also expresses a number of membrane-damaging toxins and superantigen toxins that can cause tissue damage and the symptoms of septic shock, respectively (11). There is a growing realization that S. aureus has multiple mechanisms for evading both innate immunity mediated by polymorphonuclear leukocytes (12, 13) and induced immunity mediated by both B and T cells (11, 14). Some virulence factors are expressed by genes that are located on mobile genetic elements called pathogenicity islands (e.g., toxic shock syndrome toxin–1 and some enterotoxins; ref. 15) or lysogenic bacteriophages (e.g., Panton-Valentine leucocidin [PVL]; refs. 15, 16) and factors associated with suppressing innate immunity such as the chemotaxis inhibitory protein and staphylokinase (ref. 13), which are integrated in the bacterial chromosome.

The S. aureus population is clonal

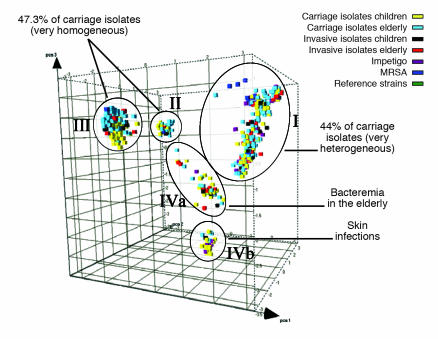

The study by Melles et al. reported in this issue of the JCI (17) examines the major questions about natural populations of S. aureus concerning clonality and virulence. The authors examined 829 S. aureus strains from healthy donors from the city of Rotterdam in The Netherlands. Selective amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) amplification analysis was used to compare genetic relatedness of strains, and this analysis revealed the existence of 3 major and 2 minor genetic clusters, subsequently confirmed by multilocus sequence typing (MLST) (Figure 2). The authors therefore concluded that the S. aureus population is clonal. These clusters corresponded to the predominant groups identified in a recent study of carriage isolates from the county of Oxfordshire in the United Kingdom using MLST (18). Thus the same clonal lineages appear to be dominant in 2 distinct geographic locations.

Figure 2.

Principal component analysis of 1,056 S. aureus strains reveals genetic clusters of hypervirulent clones (17). The different cubes, plotted here in a 3D space and colored according to their source, represent each S. aureus strain analyzed in the Melles et al. study. The 5 circles indicate the 3 major (I, II, and III) and 2 minor (IVa and IVb) different phylogenetic clusters identified by AFLP. While strains from each of the genetic clusters are essentially able to cause invasive disease, some clusters contain proportionally more invasive isolates.

Evidence for clones with enhanced virulence

Melles et al. (17) also examined a smaller number of isolates from individuals with invasive disease (bacteremia and deep-seated abscesses) as well as those from individuals with severe impetigo. There was clear evidence that some clonal types are more virulent than others in that they appeared more frequently among disease isolates than among carriage isolates (Figure 2). This sharply contrasts with the earlier Oxfordshire study, in which no evidence for hypervirulent clones was found (18). In the Melles et al. study, bacteremia in elderly patients was significantly more frequently caused by 1 strain in cluster IVa (17). In addition, strains causing severe skin infections were significantly more frequently found to be members of cluster IVb. This could be due to lysogenization of a progenitor IVb strain with the bacteriophage that encodes PVL (16), a toxin that is strongly associated with severe skin infections (19).

The question remains: Why did this study find evidence for virulent clones, whereas the Oxfordshire study did not? Perhaps this discrepancy can be attributed to the fact that Melles et al. tested a larger number of strains (17). Furthermore, the Oxfordshire study (18) was confined to isolates obtained from patients with invasive infections requiring admission to hospital and thus excluded impetigo and skin infections. Another factor might have been be the prevalence of MRSA strains present in the nosocomial invasive isolates from individuals in the UK; in contrast, of the invasive strains isolated from Dutch individuals, none were identified as MRSA. This is consistent with the conclusion that all strains of S. aureus have the potential to cause infection and that some are more virulent than others.

Evolution of MRSA

MRSA strains have emerged by acquisition of mobile genetic elements called SCCmec cassettes, which carry the mecA gene that encodes PBP2a. There are 5 different cassettes (SCCmec types I–V; refs. 3, 20, and 21). It is now clear that major MRSA clones were created on multiple occasions by acquisition of SCCmec by prevalent strains that have continued to flourish (22). None of the Dutch carriage or invasive disease isolates were found to harbor the mecA gene (17). Nevertheless, the authors examined a variety of MRSA strains from other sources and found SCCmec-containing strains in each of their major genetic clusters. This is consistent with previous studies (22) that established that MRSA strains have arisen many times by transfer of SCCmec cassettes into susceptible host strains.

PVL is a 2-component cytolytic toxin with high affinity for human leukocytes (11). It has been associated with S. aureus strains causing severe skin infections (19) and with necrotizing pneumonia in previously healthy youths (23). In the Melles et al. study (17), PVL was rarely found in the carriage isolates (0.6%) but was present in a significantly high number of strains that caused abscesses and arthritis. PVL is also expressed by the newly emerged CA-MRSA strains, which appear to have enhanced virulence (5, 23). However, Melles et al. did not examine CA-MRSA strains in this study.

Future prospects for combating S. aureus

Given the problems caused by the development of antibiotic-resistant S. aureus, vaccination may well have a significant role to play in controlling this organism in the future. A number of companies are developing products intended for active or passive immunization against S. aureus infections, including a capsular polysaccharide vaccine that has been subjected to a clinical trial with hemodialysis patients (24), a monoclonal antibody (25), and human immunoglobulin that is enriched for antibodies that recognize clumping factor A (26).

An increased understanding of how S. aureus colonizes the nares could allow improved methods for controlling nasal and skin carriage. Recent studies of mutant strains defective in wall teichoic acid (WTA) in a rat model of nasal colonization implicated WTA in colonization (27). Also, several different surface proteins can promote adherence of S. aureus to squamous epithelial cells isolated from the nares (28, 29) and could act as adhesins involved in nasal colonization. Another mystery that deserves greater attention is the question of why some members of the population never carry S. aureus, while others are persistent carriers.

The study by Melles et al. (17), in combination with MLST analysis (18), provides a solid foundation for analysis of novel hypervirulent or epidemic drug-resistant S. aureus clones that might arise in the future. One thing seems certain: S. aureus will continue to respond to challenges imposed by humans’ continued attempts to combat its carriage and development of related disease.

Footnotes

See the related article beginning on page 1732.

Nonstandard abbreviations used: AFLP, amplified fragment length polymorphism; CA-MRSA, community-acquired MRSA; MLST, multilocus sequence typing; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; PVL; Panton-Valentine leukocidin; WTA, wall teichoic acid.

Conflict of interest: The author has declared that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Peacock SJ, de Silva I, Lowy FD. What determines nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus? Trends Microbiol. 2001;9:605–610. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(01)02254-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.von Eiff C, Becker K, Machka K, Stammer H, Peters G. Nasal carriage as a source of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Study Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001;344:11–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200101043440102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hiramatsu K, Cui L, Kuroda M, Ito T. The emergence and evolution of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Trends Microbiol. 2001;9:486–493. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(01)02175-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chambers HF. Methicillin resistance in staphylococci: molecular and biochemical basis and clinical implications. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1997;10:781–791. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.4.781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vandenesch F, et al. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus carrying Panton-Valentine leukocidin genes: worldwide emergence. Emerging Infect. Dis. 2003;9:978–984. doi: 10.3201/eid0908.030089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hiramatsu K. Vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: a new model of antibiotic resistance. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2001;1:147–155. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(01)00091-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weigel LM, et al. Genetic analysis of a high-level vancomycin-resistant isolate of Staphylococcus aureus. Science. 2003;28:1569–1571. doi: 10.1126/science.1090956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eliopoulos GM. Quinupristin-dalfopristin and linezolid: evidence and opinion. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2003;36:473–481. doi: 10.1086/367662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foster TJ, Höök M. Surface protein adhesins of Staphylococcus aureus. Trends Microbiol. 1998;6:484–488. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(98)01400-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mazmanian SK, et al. Passage of heme-iron across the envelope of Staphylococcus aureus. Science. 2003;299:906–909. doi: 10.1126/science.1081147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bohach, G.A., and Foster, T.J. 1999. Staphylococcus aureus exotoxins. In Gram positive bacterial pathogens. V.A. Fischetti, R.P. Novick, J.J. Ferretti, and J.I. Rood, editors. American Society for Microbiology. Washington, D.C., USA. 367–378.

- 12.Fedtke I, Gotz F, Peschel A. Bacterial evasion of innate host defenses--the Staphylococcus aureus lesson. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2004;294:189–194. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2004.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Haas CJ, et al. Chemotaxis inhibitory protein of Staphylococcus aureus, a bacterial antiinflammatory agent. J. Exp. Med. 2004;199:687–695. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodyear CS, Silverman GJ. Death by a B cell superantigen: in vivo VH-targeted apoptotic supraclonal B cell deletion by a staphylococcal Toxin. J. Exp. Med. 2003;197:1125–1139. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Novick RP. Mobile genetic elements and bacterial toxinoses: the superantigen-encoding pathogenicity islands of Staphylococcus aureus. Plasmid. 2003;49:93–105. doi: 10.1016/s0147-619x(02)00157-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Narita S, et al. Phage conversion of Panton-Valentine leukocidin in Staphylococcus aureus: molecular analysis of a PVL-converting phage, phiSLT. Gene. 2001;268:195–206. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00390-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Melles DC, et al. Natural population dynamics and expansion of pathogenic clones of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Invest. 2004;114:1732–1740. doi:10.1172/JCI200423083. doi: 10.1172/JCI23083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feil EJ, et al. How clonal is Staphylococcus aureus? J. Bacteriol. 2003;185:3307–3316. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.11.3307-3316.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lina G, et al. Involvement of Panton-Valentine leukocidin-producing Staphylococcus aureus in primary skin infections and pneumonia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1999;29:1128–1132. doi: 10.1086/313461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ito T, et al. Novel type V staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec driven by a novel cassette chromosome recombinase, ccrC. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004;48:2637–2651. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.7.2637-2651.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ma XX, et al. Novel type of staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec identified in community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002;46:1147–1152. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.4.1147-1152.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Enright MC, et al. The evolutionary history of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002;99:7687–7692. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122108599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gillet Y, et al. Association between Staphylococcus aureus strains carrying gene for Panton-Valentine leukocidin and highly lethal necrotising pneumonia in young immunocompetent patients. Lancet. 2002;359:753–759. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07877-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fattom AI, Horwith G, Fuller S, Propst M, Naso R. Development of StaphVAX, a polysaccharide conjugate vaccine against S. aureus infection: from the lab bench to phase III clinical trials. Vaccine. 2004;17:880–887. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2003.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hall AE, et al. Characterization of a protective monoclonal antibody recognizing Staphylococcus aureus MSCRAMM protein clumping factor A. Infect. Immun. 2003;71:6864–6870. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.12.6864-6870.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vernachio J, et al. Anti-clumping factor A immunoglobulin reduces the duration of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia in an experimental model of infective endocarditis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2003;47:3400–3406. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.11.3400-3406.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weidenmaier C, et al. Role of teichoic acids in Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization, a major risk factor in nosocomial infections. Nat. Med. 2004;10:243–245. doi: 10.1038/nm991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roche FM, Meehan M, Foster TJ. The Staphylococcus aureus surface protein SasG and its homologues promote bacterial adherence to human squamous nasal epithelial cells. Microbiology. 2003;149:2759–2767. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26412-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O’Brien LM, Walsh EJ, Massey RC, Peacock SJ, Foster TJ. Staphylococcus aureus clumping factor B (ClfB) promotes adherence to human type I cytokeratin 10: implications for nasal colonization. Cell. Microbiol. 2002;4:759–770. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2002.00231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]