Abstract

This phase I study assessed the safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of RN317 (PF‐05335810), a specifically engineered, pH‐sensitive, humanized proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin type 9 (PCSK9) monoclonal antibody, in hypercholesterolemic subjects (low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL‐C) ≥ 80 mg/dl) 18–70 years old receiving statin therapy. Subjects were randomized to: single‐dose placebo, RN317 (subcutaneous (s.c.) 0.3, 1, 3, 6, or intravenous (i.v.) 1, 3, 6 mg/kg), or bococizumab (s.c. 1, 3, or i.v. 1 mg/kg); or multiple‐dose RN317 (s.c. 300 mg every 28 days; three doses). Of 133 subjects randomized, 127 completed the study. RN317 demonstrated a longer half‐life, greater exposure, and increased bioavailability vs. bococizumab. RN317 was well tolerated, with no subjects discontinuing because of treatment‐related adverse events. RN317 lowered LDL‐C by up to 52.5% (day 15) following a single s.c. dose of 3.0 mg/kg vs. a maximum of 70% with single‐dose bococizumab s.c. 3.0 mg/kg. Multiple dosing of RN317 produced LDL‐C reductions of ∼50%, sustained over an 85‐day dosing interval.

Study Highlights

WHAT IS THE CURRENT KNOWLEDGE ON THIS TOPIC?

✓ Monoclonal antibodies against PCSK9 can produce substantial reductions in LDL‐C in hypercholesterolemic subjects. However, monthly dosing regimens often result in a suboptimal “saw‐tooth” pattern of LDL‐C reductions from baseline.

WHAT QUESTION DID THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

✓ This study assessed whether a pH‐sensitive, humanized IgG2Δa, monoclonal PCSK9 antibody (RN317) could be specifically engineered to eliminate target‐mediated drug clearance, and thus prolong the half‐life and sustain the duration of LDL‐C lowering when compared with the monoclonal PCSK9 antibody bococizumab.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS TO OUR KNOWLEDGE

✓ An anti‐PCSK9 monoclonal antibody can be engineered to produce a pH‐sensitive antibody, which prolongs half‐life and extends the duration of LDL‐C lowering.

HOW THIS MIGHT CHANGE CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY OR TRANSLATIONAL SCIENCE

✓ A detailed knowledge of anti‐PCSK9 monoclonal antibody structure has allowed antibody engineering to proceed on a rational basis to enhance the pharmacological properties of these molecules. These techniques could be utilized in other therapeutic applications.

The serine protease proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin type 9 (PCSK9) binds to and downregulates low‐density lipoprotein receptor (LDL‐R) levels on hepatocytes.1, 2 A decrease in active circulating PCSK9 causes a rise in hepatocyte LDL‐R density, thereby increasing LDL uptake from the circulation leading to a reduction in serum LDL cholesterol (LDL‐C) levels.2, 3 The benefits to long‐term cardiovascular (CV) health by lowering LDL‐C are well known,4 and loss‐of‐function mutations in the PCSK9 gene have been associated with reduced LDL‐C levels and a reduced risk for CV events.5 Conversely, gain‐of‐function mutations in the PCSK9 gene results in an increase in LDL‐C levels, and has been associated with an increase in long‐term CV risk.6 These observations have led to the inhibition of PCSK9 being a major target for the development of therapies to reduce LDL‐C, which may complement the action of statins.7

A series of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) have been specifically developed to inhibit the activity of PCSK9.7 The mAb bococizumab (previously known as PF‐04950615/RN316) targets the LDL‐R binding domain of PCSK9 with high affinity, preventing binding with and downregulation of LDL‐R, leading to improved LDL‐C clearance, and ultimately a reduction in serum LDL‐C.8 Phase I and IIA trials of bococizumab in both statin‐ and nonstatin‐treated subjects have demonstrated that it is well tolerated and associated with substantial reductions in LDL‐C of up to 70–80%.9, 10 A phase IIB clinical trial of bococizumab conducted in statin‐treated subjects with hypercholesterolemia confirmed the findings of these early small trials.11 Bococizumab is now being evaluated in the phase III SPIRE (Studies on PCSK9 Inhibition and the Reduction of Vascular Events) program.11

A routine finding from most early dose‐ranging studies of PCSK9‐inhibiting mAbs was that LDL‐C values were not maintained between monthly doses, resulting in a suboptimal “saw‐tooth” pattern of LDL‐C levels from baseline, even in patients receiving ongoing statin therapy.11, 12, 13, 14 Recent evidence suggests that achieving sustained reductions in CV risk factors, such as LDL‐C and blood pressure (BP), may be an important consideration for optimal management of CV risk.15, 16 For example, visit‐to‐visit variability in LDL‐C levels has been identified as an independent predictor of CV events in patients with coronary artery disease, with higher variability associated with a higher incidence of CV events.15 By preventing variations in LDL‐C reduction between doses, PCSK9 inhibitors with a longer duration of action may provide additional clinical benefit and should be investigated further.

With the aim of sustaining the physiological activity of PCSK9 inhibition, a humanized IgG2Δa, monoclonal PCSK9 antibody, RN317 (PF‐05335810), was specifically engineered to have pH‐sensitive binding to PCSK9 in order to reduce target‐mediated drug clearance, thus prolonging the half‐life and sustaining the duration of LDL‐C lowering.17 By incorporating histidines into the complementary region residues, RN317 shows lower affinity for PCSK9 at low acidic pH compared with neutral pH, allowing RN317 to bind and block PCSK9 function in the blood (pH neutral), but to disassociate from PCSK9 in the acidic endosomal compartment and escape PCSK9‐mediated degradation.17 This enables RN317 to be recycled and then potentially reused, prolonging the entity's half‐life and increasing exposure.17 Consistent with these engineered characteristics, RN317 demonstrated prolonged half‐life and increased duration of LDL‐C lowering compared with bococizumab in studies conducted in mice and cynomolgus monkeys.17 The phase I clinical study described here was undertaken to assess the safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics of RN317 in hypercholesterolemic subjects receiving ongoing statin therapy. In addition, the effect of RN317, administered as either a subcutaneous (s.c.) or intravenous (i.v.) dose, on plasma LDL‐C levels was assessed and compared with that known for bococizumab.

METHODS

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consent

This randomized, placebo‐controlled, ascending‐dose, phase I trial was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and all International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) Good Clinical Practice (GCP) guidelines. In addition, all local regulatory requirements were followed. The study protocols and the informed consent documents were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Boards and/or Independent Ethics Committees at each participating center. All subjects provided their informed consent. The study is listed on clinicaltrials.gov with the identifier: NCT01720537.

Study population

Subjects were recruited from seven centers in the United States. Men and women aged 18–70 years with a diagnosis of hypercholesterolemia and prescribed atorvastatin 40 mg/day, simvastatin 40 mg/day, or rosuvastatin 20 mg/day for at least 45 days prior to study start were eligible for enrollment. Subjects who had changed their dose of lipid‐lowering medication within 45 days of study start were excluded. Lipid‐lowering herbal supplements were not allowed. All eligible subjects had a fasting LDL‐C ≥ 80 mg/dl at both screening and 1 week before randomization. Subjects had to have a body mass index (BMI) between 18.5 and 45 kg/m2 and body weight ≤ 150 kg (Cohorts 1–3), or ≤ 125 kg (Cohorts 4 and 6, see below). Key exclusion criteria included: a history of a cardiovascular disease or cerebrovascular event(s) or procedure within 1 year of randomization; poorly controlled diabetes (glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) > 9%); hypertension (systolic BP > 160 mm Hg or diastolic BP > 90 mm Hg); any known sensitivity to anti‐PCSK9 compounds; and any other chronic medical condition considered by the investigators to be clinically relevant. Subjects were also excluded if on screening they had serum creatinine > 1.5 times the upper limit of normal (ULN), or alanine aminotransferase (ALT) or aspartate aminotransferase (AST) ≥ 2.0 times the ULN. Exposure to bococizumab was allowed provided the subject tested negative for anti‐bococizumab antibodies before the start of this study and > 6 months had elapsed since the last dose of bococizumab.

Study design

In total, 133 subjects with a diagnosis of hypercholesterolemia and currently receiving statin therapy were randomized into six cohorts, between 10 July 2012 and 28 October 2013. Prior to dosing, a randomization/treatment assignment number was allocated that was retained throughout the study and corresponded to a treatment group determined by a randomization/treatment assignment generated by the sponsor. Depending on allocation, subjects received: single‐dose placebo (s.c. or i.v.), single‐dose RN317 (s.c. 0.3, 1, 3, or 6 mg/kg, or i.v. 1, 3, and 6 mg/kg), or single‐dose bococizumab (s.c. 1 and 3 mg/kg, or i.v. 1 mg/kg) (Cohorts 1–4 and 6). To determine the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) of RN317, Cohort 5 received open‐label RN317 (s.c. 300 mg Q28d, for three doses) following a dose‐escalation strategy (Supplementary Figure S1). Screening and follow‐up periods varied depending on cohort. For RN317 and bococizumab single‐dose cohorts (Cohorts 1–4 and 6), screening lasted for up to 28 days, with a77‐day treatment period and 7‐day follow‐up period. For subjects in Cohort 5 (multiple‐dose cohort), the screening period lasted for up to 28 days, the treatment period for ∼85 days, and the follow‐up period for ∼84 days. In this open‐label portion, subjects received three doses of RN317 (s.c. 300 mg on days 1, 29, and 57). With the exception of Cohort 5, subjects and investigators were blinded to study treatment.

The doses of RN317 selected for the single‐dose studies were based on preclinical pharmacology and pharmacokinetic and toxicology studies. The dose selected for the multiple‐dose experiments was based on the findings of population pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic modeling of results of the single‐dose studies.

Outcome assessments

This study assessed the safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and immunogenicity of single, ascending s.c. and i.v. doses, and multiple s.c. doses, of RN317 vs. placebo, and vs. bococizumab. The proportion of subjects having a ≥ 50% reduction from baseline in LDL‐C over days 8–85 for single‐dose and days 8–169 for multiple‐dose cohorts was also assessed. The incidence, severity, and causal relationship of treatment‐emergent adverse events (AEs) were monitored alongside dose‐limiting or intolerable AEs and abnormal laboratory findings (clinical chemistry, hematology, and urinalysis), or clinically relevant changes in vital signs, BP, or electrocardiograph parameters, or exacerbations of existing conditions. Blood samples for pharmacokinetic and lipid and biomarker analyses were performed throughout the study on scheduled visits. Exploratory end points included absolute and percentage changes from baseline in LDL‐C, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL‐C), and triglycerides (TG).

Blood sample collection

Blood samples were collected on day 1 (predose, and 1, 2, 3, and 4 h postdose), day 2 (24 h postdose), day 3 (48 h postdose), day 4 (72 h postdose), and then once‐weekly for 12 weeks until day 85 (2,016 h postdose). Lipid particles, apolipoprotein A1 (apoA1), apoB, lipoprotein(a) (Lp[a]), C‐reactive protein (CRP), and other biomarkers related to hypercholesterolemia as well as antidrug antibodies (ADAs) (anti‐RN317 or anti‐bococizumab) were assayed from blood samples collected on days 1, 4, 15, 29, 57, and 85 (or on the last follow‐up visit). Samples were analyzed at ICON Solutions (Whitesboro, New York, NY), QPS Holdings (Newark, DE), or LipoScience (Raleigh, NC).

Laboratory methods

Cholesterol and TG were assayed using enzymatic methods. LDL‐C was calculated with the Friedewald formula: LDL‐C = total cholesterol – HDL‐C – (TG × 0.2).

Pharmacokinetic profiling of RN317 was carried out using a validated, sensitive, and specific enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) method (QPS Holdings). This research assay measured free and target‐bound RN317, but not other RN317 bound complexes. In this assay, anti‐idiotypic antibody was utilized as a capturing reagent. The samples were preprocessed with a 1:500 dilution using block/dilution buffer containing an excess of a mouse anti‐PCSK9 antibody to competitively displace RN317 from its complex with the PCSK9 target. The RN317 concentration range for the standard curve was from 200–10,000 ng/ml.

Pharmacokinetics of bococizumab was studied using a validated ELISA for determining free and target‐bound bococizumab in plasma (ICON Development Solutions). This research assay does not detect all target‐bound bococizumab and was used to support early clinical development. Bococizumab concentrations were determined using a four‐parameter logistic fit of the standard curve (range: 200–51,200 ng/ml).

Assay performance for both RN317 and bococizumab was checked using three quality control (QC) samples assayed in two replicates on each plate. Assays were acceptable if the precision (coefficient of variation, %CV) of each QC sample was ≤ 20% (≤ 25% at LLOQ) and intrabatch accuracy (percent relative error, %RE) within 20% (25% at the LLOQ).

Pharmacokinetic assessments

Pharmacokinetic parameters were derived from blood samples following RN317 and bococizumab administration, and included maximum plasma concentrations (Cmax), time to maximum plasma concentration (Tmax), area under the plasma concentration‐time curve (AUC) from time zero to infinity (AUCinf), AUC from time zero to last quantifiable concentration (AUClast), clearance (CL/F or CL), and terminal half‐life (t1/2). Cohort 5 additionally included volume of distribution (Vz or Vss) and the observed accumulation ratio based on AUC (Rac).

Detection of human ADAs and injection site reactions

Immunogenicity to RN317 and bococizumab was detected using validated ELISA assays against human ADAs (anti‐RN317 or anti‐bococizumab). For RN317 this was conducted at QPS Holdings. For bococizumab this was conducted by ICON Development Solutions. RN317 samples were considered positive when the titer value was > 1.602. Bococizumab samples were considered positive when the titer value was ≥4.32. Subjects allocated to either RN317 or bococizumab with detectable ADAs were closely observed for hypersensitivity reactions, including (but not limited to) changes in platelet or white blood cell counts and vital signs.

Statistical analysis

All randomized subjects who received any amount of study medication were included in the safety, pharmacokinetic, and pharmacodynamic assessments, and for other exploratory end points.

Demographic and baseline characteristics were summarized by treatment groups. Means with standard deviations (SDs) and medians with ranges were used for continuous variables. Counts and proportions were used for categorical variables. Pharmacokinetic parameters were summarized and 90% confidence intervals (CIs) calculated. Data were dose‐normalized to 1 mg/kg. Absolute bioavailability was estimated by comparing log‐transformed AUCinf (if data permitted) and AUClast for RN317 or bococizumab administered s.c. (Test) and RN317 or bococizumab administered i.v. (Reference), respectively. Pharmacokinetic parameters (CL or AUC, Cmax, t1/2 and %F if data permitted) for RN317 and bococizumab from Cohorts 2 and 3 by route of administration were compared using analysis of variance. For this comparison, natural log‐transformed Cmax, AUClast, and t1/2 from RN317 (Test) and bococizumab (Reference) were analyzed using mixed effect mode with treatment as a fixed effect and subject within cohort as a random effect. No adjustment was required for molecular weight, as this does not differ significantly between RN317 and bococizumab. Safety data were analyzed using descriptive statistics. For exploratory end points, percentage changes from baseline (with 90% CI) in lipids of each treatment arm were measured, and the absolute and percentage change from baseline calculated. Data were analyzed using SAS (v. 9, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Study population

A total of 133 subjects were randomized to treatment and all received investigational products (RN317, n = 78; placebo, n = 21; bococizumab, n = 34) (Table 1). The majority of subjects were male (63.2%) and white (83.5%). Additional demographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Supplementary Table S1. Overall, 127 subjects completed the study with six subjects having discontinued (Supplementary Figure S2). The most common reason stated for discontinuation was: “no longer willing to participate in study” (five subjects; Supplementary Figure S2).

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline characteristics of the study population

| Single Dose | Multiple Dose | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | RN317 | Bococizumab | RN317 | ||||||||||

| s.c. | i.v. | s.c. | s.c. | s.c. | s.c. | i.v. | i.v. | i.v. | s.c. | s.c. | i.v. | s.c. | |

| 0.3 mg/kg | 1 mg/kg | 3 mg/kg | 6 mg/kg | 1 mg/kg | 3 mg/kg | 6 mg/kg | 1 mg/kg | 3 mg/kg | 1 mg/kg | 300 mg | |||

| (n = 13) | (n = 8) | (n = 6) | (n = 12) | (n = 16) | (n = 6) | (n = 11) | (n = 6) | (n = 6) | (n = 12) | (n = 16) | (n = 6) | (n = 15) | |

| Age, years | 59.0 | 62.3 | 60.3 | 59.4 | 50.7 | 62.5 | 57.8 | 61.2 | 54.3 | 60.1 | 55.6 | 61.5 | 55.8 |

| (8.3) | (3.9) | (6.8) | (6.8) | (12.7) | (8.3) | (7.8) | (4.7) | (9.3) | (8.1) | (9.1) | (5.9) | (9.7) | |

| Male | 7 (53.8) | 1 (12.5) | 1 (16.7) | 8 (66.7) | 11 (68.8) | 5 (83.3) | 7 (63.6) | 4 (66.7) | 6 (100) | 9 (75.0) | 9 (56.3) | 5 (83.3) | 11 (73.3) |

| White | 10 (76.9) | 7 (87.5) | 5 (83.3) | 11 (91.7) | 10 (62.5) | 5 (83.3) | 8 (72.7) | 5 (83.3) | 5 (83.3) | 11 (91.7) | 13 (81.3) | 6 (100) | 15 (100) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 32.5 | 33.4 | 32.9 | 29.7 | 30.6 | 30.0 | 30.6 | 29.3 | 33.4 | 33.3 | 29.2 | 32.6 | 32.0 |

| (5.2) | (5.8) | (5.7) | (7.1) | (5.7) | (5.7) | (5.8) | (4.9) | (5.1) | (6.5) | (4.2) | (4.8) | (6.1) | |

| Lipids, mg/dl | |||||||||||||

| LDL‐C | 105.7 | 110.7 | 102.9 | 102.8 | 132.9 | 103.7 | 109.8 | 117.8 | 133.0 | 96.3 | 128.8 | 91.4 | 106.6 |

| (28.8) | (15.1) | (13.6) | (13.9) | (57.4) | (14.4) | (24.4) | (19.7) | (30.9) | (30.3) | (33.3) | (16.5) | (20.9) | |

| HDL‐C | 44.1 | 57.4 | 57.3 | 56.3 | 47.2 | 51.2 | 49.6 | 46.0 | 38.5 | 44.8 | 51.8 | 60.7 | 46.2 |

| (7.56) | (11.4) | (10.0) | (13.1) | (9.96) | (17.6) | (16.3) | (6.8) | (5.87) | (9.88) | (13.6) | (26.3) | (10.8) | |

| Triglycerides | 154.2 | 132.9 | 140.1 | 147.2 | 164.4 | 146.8 | 114.2 | 137.8 | 194.9 | 152.1 | 138.8 | 133.3 | 136.9 |

| (37.4) | (55.6) | (33.3) | (48.4) | (94.8) | (89.6) | (37.3) | (70.4) | (64.7) | (114.1) | (56.5) | (67.5) | (39.9) | |

| TC | 178.6 | 194.7 | 188.3 | 188.5 | 213.0 | 184.0 | 182.2 | 191.5 | 210.5 | 171.0 | 208.4 | 178.7 | 183.0 |

| (34.9) | (16.4) | (21.5) | (15.6) | (63.7) | (20.0) | (30.5) | (28.4) | (32.2) | (35.6) | (41.0) | (37.3) | (25.5) | |

Values are mean (SD), or number (%). BMI, body mass index; LDL‐C, low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL‐C, high‐density lipoprotein cholesterol; TC, total cholesterol; SD, standard deviation.

Pharmacokinetic profiles of RN317 and bococizumab

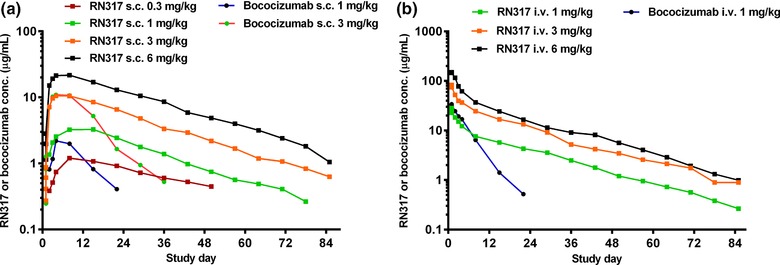

Single dose: Absorption was slow and varied across the dose range (0.3–6.0 mg/kg) following single s.c. administration of RN317, and the maximum concentration (Cmax) was reached at between 3 and 10.5 days, depending on the dosage (Table 2; Figure 1 a). Following Cmax, a multiphasic decline over time was recorded (Figure 1 a), with mean terminal t1/2 values of 19–21 days (RN317 s.c. 1.0–6.0 mg/kg) (Table 2). Plasma concentrations with i.v. RN317 (1.0–6.0 mg/kg) exhibited a multiphasic decline over time as was seen following s.c. dosing (Figure 1 b), with mean terminal t1/2 values of 15–19 days across the dose range, which were similar to those observed following s.c. doses (Table 2). Overall, exposure across i.v. doses increased in an approximately dose‐proportional manner, although RN317 mean AUC and Cmax values for i.v. 6.0 mg/kg dose were slightly lower (∼20–30% lower) compared with i.v. 1.0 and 3.0 mg/kg doses of RN317. Absolute bioavailability for s.c. RN317 compared with i.v. administration ranged from 38.5–67.5%, based on a dose‐normalized AUC from time zero to infinity (AUCinf). Absolute bioavailability for bococizumab s.c. 1.0 mg/kg compared with bococizumab i.v. infusion was 12.5%. Bioavailability was 44.6% for bococizumab s.c. 3.0 mg/kg using dose‐normalized AUC for i.v. 1.0 mg/kg as referent. Additional pharmacokinetic parameters for the single‐dose cohorts are presented in Supplementary Table S2.

Table 2.

Pharmacokinetic parameters following single doses of RN317 or bococizumab in subjects with hypercholesterolemia receiving ongoing statin therapy

| RN317 | Bococizumab | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| s.c. | s.c. | s.c. | s.c. | i.v. | i.v. | i.v. | s.c. | s.c. | i.v. | |

| 0.3 mg/kg | 1 mg/kg | 3 mg/kg | 6 mg/kg | 1 mg/kg | 3 mg/kg | 6 mg/kg | 1 mg/kg | 3 mg/kg | 1 mg/kg | |

| (n = 6) | (n = 12) | (n = 16) | (n = 6) | (n = 11) | (n = 6) | (n = 6) | (n = 12) | (n = 16) | (n = 6) | |

| n * | 6 | 12 | 16 | 6 | 11 | 6 | 6 | 12 | 16 | 6 |

| Cmax, μg/ml | 1.172 | 3.099 | 11.09 | 23.02 | 35.7 | 86.01 | 157.8 | 1.824 | 11.85 | 35.89 |

| (20) | (33) | (35) | (28) | (195) | (12) | (9) | (65) | (66) | (12) | |

| Tmax, h | 253 | 253 | 120 | 72 | 2.0 | 2.51 | 2.00 | 156 | 72.0 | 1.50 |

| (143–339) | (72–504) | (24–672) | (72–337) | (0.967–4.00) | (1.00–4.00) | (1.00–3.00) | (48.0–171) | (4.00–168) | (1.00–4.00) | |

| N* | 2 | 8 | 16 | 6 | 11 | 6 | 6 | 1 | 10 | 6 |

| AUCinf, μg.h/ml | NR | 3,103 | 7,995 | 18,100 | 6,705 | 19,420 | 29,220 | NR | 3,721 | 3,451 |

| (30) | (32) | (30) | (22) | (13) | (6) | (47) | (13) | |||

| t1/2, days | NR | 20.88 ± 4.33 | 19.40 ± 5.40 | 18.58 ± 4.1 | 19.49 ± 6.43 | 17.52 ± 2.9 | 14.63 ± 4.68 | NR | 8.378 ± 2.656 | 3.400 ± 0.692 |

Data shown are geometric mean (coefficient of variation; %CV) for all parameters except for Tmax where median (min, max) is shown, and t1/2 where arithmetic mean ± SD is shown.

*n is the number of subjects in the treatment group and contributing to the mean; N is the number of subjects with a well‐characterized terminal phase. AUCinf, area under the plasma concentration–time curve from time zero to infinity; Cmax, maximum concentration; NR, not reported where <3 subjects had reportable parameter values; SD, standard deviation; t1/2, terminal half‐life; Tmax, time to reach maximum concentration.

Figure 1.

Plasma RN317 and bococizumab concentration–time profiles following (a) single s.c. or (b) single i.v. doses. Values are median.

Multiple dose: Following RN317 s.c. 300 mg every 28 days (Q28d), Cmax was reached within ∼3 days after dosing. Accumulation of RN317 was minimal, with a mean accumulation ratio (Rac) of 1.23 after Q28d dosing for 3 months (Table 3). Additional pharmacokinetic parameters for the multiple‐dose cohort are presented in Supplementary Table S3.

Table 3.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of multiple‐dose RN317 s.c. 300 mg dosing (Q28d) in subjects with hypercholesterolemia receiving ongoing statin therapy

| RN317 300 mg s.c. dose at day 57 | |

|---|---|

| (n = 13) | |

| n * | 13 |

| Cmax, μg/ml | 16.06 (38) |

| Tmax, h | 72.2 (70.3–169) |

| N* | 13 |

| AUCtau, μg.h/ml/mg | 7,692 (37) |

| Rac | 1.226 (16) |

| t1/2, days | 18.77 ± 3.82 |

Data shown are geometric mean (%CV) for all parameters except for Tmax where median (min, max) is shown, and t1/2 where arithmetic mean ± SD is shown.

*n is the number of subjects in the treatment group and contributing to the mean; N is the number of subjects with a well‐characterized terminal phase. AUCtau, area under the plasma concentration–time curve during a dosage interval (tau); Cmax, maximum concentration; Rac, observed accumulation ratio based on AUC; SD, standard deviation; t1/2, terminal half‐life; Tmax, time to reach maximum concentration.

Comparing the pharmacokinetics of RN317 with bococizumab

Bococizumab exposure increased in a greater than dose‐proportional manner from s.c. 1.0 to 3.0 mg/kg. Comparing the same routes of administration and dosages of RN317 and bococizumab, RN317 showed a more sustained plasma concentration–time profile vs. bococizumab (Figure 1). Single‐dose s.c. and i.v. RN317 and bococizumab showed comparable Cmax and time to reach maximum concentration (Tmax) for the same dose regimen. However, AUClast was higher and apparent terminal half‐life (t1/2) was longer for RN317 in comparison with bococizumab (Table 2). For example, mean t1/2 was 19.49 days for RN317 and 3.4 days for bococizumab for the i.v. 1.0 mg/kg dose (Table 2). As a result, based on the ratios (90% CI) of adjusted geometric mean values for AUClast using noncompartmental analysis, the relative bioavailability was higher for RN317 compared with bococizumab, with ratios of 619.05 (95% CI 304.15, 1260.0) for RN317 s.c. 1.0 mg/kg vs. bococizumab s.c. 1.0 mg/kg as referent and 191.01 (95% CI 156.17, 233.62) for RN317 i.v. 1.0 mg/kg vs. bococizumab i.v. 1.0 mg/kg as referent.

Safety and tolerability

The incidence of AEs was similar for all RN317 or bococizumab treatment arms (with either s.c. or i.v. dosing). There was no clear dose relationship observed between the dose of RN317 and the incidence of AEs, either all‐causality or treatment‐related (Table 4; Supplementary Table S4). The most frequent AEs (all‐causality across all treatment arms and dosing schedules) were upper respiratory tract infection (RN317, n = 5; bococizumab, n = 7), headache (placebo, n = 4; RN317, n = 4; bococizumab, n = 3), and diarrhea (placebo, n = 2; RN317, n = 4; bococizumab, n = 1) (Supplementary Table S4).

Table 4.

Safety summary for single‐ and multi‐dose RN317 and single‐dose bococizumab in subjects with hypercholesterolemia receiving ongoing statin therapy

| RN317 | Bococizumab | RN317 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single dose | Single dose | Multiple dose | |||||||||||

| s.c. | s.c. | s.c. | s.c. | i.v. | i.v. | i.v. | s.c. | s.c. | i.v. | s.c. | |||

| Placebo | 0.3 mg/kg | 1 mg/kg | 3 mg/kg | 6 mg/kg | 1 mg/kg | 3 mg/kg | 6 mg/kg | 1 mg/kg | 3 mg/kg | 1 mg/kg | 300 mg | Total | |

| (n = 21) | (n = 6) | (n = 12) | (n = 16) | (n = 6) | (n = 11) | (n = 6) | (n = 6) | (n = 12) | (n = 16) | (n = 6) | (n = 15) | (n = 133) | |

| Subjects with AEs* | 12 (4) | 4 (2) | 6 (3) | 7 (1) | 4 (1) | 6 (3) | 2 (0) | 3 (1) | 10 (3) | 7 (2) | 6 (2) | 8 (2) | 75 (24) |

| Subjects with SAEs* | 1 (0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0) | 3 (0) |

| Subjects discontinued treatment due to AEs* | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0) | 1 (0) |

| Treatment‐related AEs (n [%])** | |||||||||||||

| Headache | 2 (9.5) | 1 (16.7) | 1 (8.3) | 0 | 0 | 2 (18.2) | 0 | 0 | 1 (8.3) | 0 | 1 (16.7) | 0 | 8 (6.0) |

| Diarrhea | 1 (4.8) | 0 | 1 (8.3) | 0 | 1 (16.7) | 1 (9.1) | 0 | 1 (16.7) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 (3.8) |

| Muscle spasms | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (6.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (6.3) | 0 | 0 | 2 (1.5) |

| Rash | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (16.7) | 1 (6.7) | 2 (1.5) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (16.7) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (1.5) |

*Values are number with all‐causality (treatment‐related) AEs, SAEs, or discontinuation of treatment due to AEs.

**Treatment‐related AEs in descending order of frequency reported in two or more subjects. AEs, adverse events; SAEs, serious adverse events.

Overall, serious adverse events (SAEs) during the treatment period were rare (four SAEs in three subjects, across all treatment arms). One subject in Cohort 5 discontinued treatment at day 30, after receiving two doses of RN317 s.c. 300 mg Q28d, due to a nontreatment‐related SAE of myocardial infarction (MI). The SAE resolved and the subject received no further doses of RN317 but completed the remaining study visits. One subject (from the s.c. placebo group) had hip pain secondary to avascular necrosis, and one subject (from the RN317 i.v. 3.0 mg/kg group) recorded two SAEs (depression and suicidal attempt). None of these SAEs were considered treatment‐related. Regarding injection‐site tolerability, most injection‐site reactions following s.c. or i.v. RN317 dosing were of mild severity, and only two subjects experienced injection‐site reactions considered of moderate severity. One subject (RN317 s.c. 3.0 mg/kg) showed bruising. Most injection‐site reactions following s.c. bococizumab dosing were also of mild severity, with one subject (bococizumab s.c. 3.0 mg/kg) who experienced redness. There did not appear to be a dose‐dependent effect of RN317 or bococizumab on either the severity of or occurrences of laboratory abnormalities.

Immunogenicity

Four subjects were positive for RN317 ADAs (defined as titer value of > 1.60) evenly distributed across treatment arms (RN317 s.c. 0.3 mg/kg, n = 1; i.v. 1.0 mg/kg, n = 1; i.v. 6.0 mg/kg, n = 2). All RN317 ADAs resolved as titer values fell below 1.6 by the end of follow‐up (days 85–265). Subjects with RN317 ADAs had no AEs that were considered drug‐related, and the pharmacokinetics of RN317 was not affected in these patients. No subjects had detectable bococizumab ADAs during the study period.

Effect of RN317 and bococizumab on LDL‐C and other lipid parameters

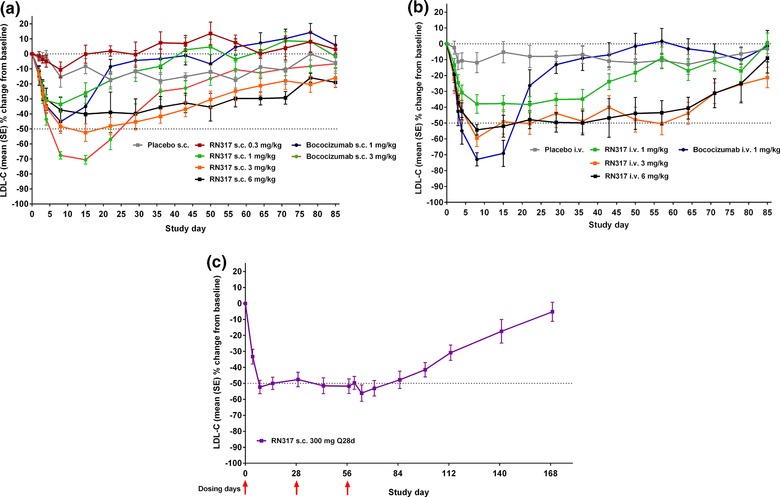

Single dose: RN317 reduced LDL‐C across the dose range following s.c. and i.v. dosing, generally in a dose‐dependent manner (Figure 2). Following single‐dose s.c. RN317, mean percentage decreases from baseline in LDL‐C ranged from 0.2–52.5% across the dose range, compared with 5.9–15.3% with placebo (Figure 2 a). Mean percentage reductions in LDL‐C from baseline of ≤ 50% (s.c. 3.0 mg/kg) and ≤ 40% (s.c. 6.0 mg/kg) were noted as early as day 8 with RN317, and reduction in LDL‐C was maintained to day 29, after which levels gradually returned towards baseline. The maximum percentage reduction from baseline in LDL‐C with s.c. RN317 was recorded on day 15 (52.5% reduction from baseline following RN317 s.c. 3.0 mg/kg). The same dose of bococizumab (s.c. 3.0 mg/kg) produced a greater percentage reduction from baseline in LDL‐C of 70% on day 15.

Figure 2.

Effect of (a) single s.c. or (b) single i.v. doses of RN317 and bococizumab (RN316/PF‐04950615), or (c) s.c. multi‐dose of RN317, on serum levels of LDL‐C.

Overall, 56% of subjects receiving RN317 s.c. 3.0 mg/kg achieved a ≥ 50% reduction from baseline in LDL‐C over to day 8, which was maintained to day 15 before steadily declining from days 22 to 85. An equivalent s.c. dose of bococizumab (3.0 mg/kg) resulted in 100% of subjects achieving a ≥ 50% reduction in LDL‐C from baseline at day 8. However, the percentage of subjects achieving a ≥ 50% reduction in LDL‐C generally declined more rapidly than for subjects who received RN317.

The magnitude and duration of LDL‐C reduction with i.v. RN317 was generally greater than that observed with s.c. dosing (Figure 2 b). A mean reduction of 40–50% was maintained consistently over the 64‐day follow‐up with the higher doses of RN317 (i.v. 3.0 and 6.0 mg/kg). The maximum percent reduction from baseline in LDL‐C with i.v. RN317 was recorded on day 8 (59% from baseline following i.v. 3.0 mg/kg). Bococizumab s.c. and i.v. generally produced greater LDL‐C reduction compared with s.c. and i.v. RN317, respectively, with maximum percent reduction in LDL‐C from baseline seen following i.v. 1.0 mg/kg on day 8 (70% vs. 40% with i.v. RN317 of the equivalent dose).

In general, HDL‐C levels increased in a dose‐dependent manner for both RN317 and bococizumab. For RN317, HDL‐C increased from baseline to day 8 with a magnitude and duration generally greater and quicker for the i.v. vs. s.c. doses. Subjects receiving RN317 i.v. 3.0 mg/kg had the greatest mean percentage increase from baseline in HDL‐C (17.4% at day 43). The corresponding RN317 s.c. 3.0 mg/kg dose exhibited a maximum 15.5% increase from baseline at day 50. For bococizumab, HDL‐C increased from baseline to day 15 with subjects receiving i.v. 1.0 mg/kg showing the highest mean percent increase from baseline (14.4% at day 15). Levels of TG for both RN317 and bococizumab, for either s.c. or i.v. doses, were variable but with no observable trends.

Multiple dose: Consistent and sustained reduction in LDL‐C was observed following RN317 s.c. 300 mg (Q28d) administration, with percentage change from baseline in LDL‐C maintained at ∼50% for up to day 85 (Figure 2 c). The proportion of subjects achieving ≥ 50% reduction in LDL‐C from baseline increased with RN317 Q28d between days 8 and 15, before stabilizing. By day 71, more than half of all subjects (64.3%) had achieved a ≥ 50% reduction in LDL‐C from baseline. Following RN317 s.c. 300 mg Q28d, minimal fluctuation in LDL‐C lowering was noted, and the ratio of the difference between the maximum and minimum LDL‐C percentage change from baseline (trough‐to‐nadir ratio) was > 0.9 throughout the study period. The largest mean increase from baseline in HDL‐C was 15.8%, observed on day 43. Smaller increases in HDL‐C were observed at days 8 and 15, with increases from baseline of 7.9% and 11.7%, respectively. There were no discernible patterns in the levels of TG throughout the study period, as levels were variable for the RN317 single‐ and multiple‐dose cohorts.

DISCUSSION

This multiarm phase I study demonstrated that the specifically engineered, pH‐sensitive, monoclonal PCSK9 antibody, RN317, was safe and well tolerated when administered as single s.c. or i.v. doses (up to 6 mg/kg) or multiple doses (s.c. 300 mg Q28d), in subjects with a diagnosis of hypercholesterolemia receiving ongoing statin therapy. Consistent with nonclinical findings,8, 17 RN317 had a longer apparent half‐life, greater exposure, and improved relative s.c. bioavailability compared with bococizumab. Although we noted a sizeable placebo effect (with an up to 15% reduction from baseline levels in LDL‐C), RN317 significantly reduced LDL‐C following single‐dose administration, producing an up to 53% reduction from baseline levels and with up to 56% of subjects achieving a ≥ 50% reduction from baseline between days 8–15. Interestingly, single 3‐ and 6‐mg/kg s.c. doses of RN317 produced similar reductions in LDL‐C despite a near‐proportional increase in drug exposure. This suggests that the maximal LDL‐C lowering by RN317 was saturated at 3 mg/kg. Increased exposure in the 6 mg/kg dose allowed prolonged LDL‐C lowering. Following multiple‐dose administration (s.c. 300 mg Q28d), RN317 produced sustained reductions in LDL‐C (of ∼50% from baseline levels) throughout the 85‐day follow‐up. Despite increased exposure and significant reductions in LDL‐C with RN317, single‐dose LDL‐C reductions were lower than that observed with bococizumab, perhaps due to low efficacy of RN317 compared with bococizumab, as suggested by the IC50 of RN317 for human PCSK9 being in the low nanomolar range (KD = 0.38 nM at pH 7.4, or 3.50 nM at pH 6)17 compared with a low picomolar binding range for bococizumab (KD = 5 pM).8 More specifically, single‐dose bococizumab produced maximum LDL‐C reductions of up to 70%, and 100% of subjects receiving bococizumab s.c. 3 mg/kg achieved a ≥ 50% reduction from baseline at day 8. These reductions are in line with data and modeled predictions from other clinical studies of bococizumab, using a similar assay technique.9, 10, 11, 18

The pharmacokinetic characteristics of PCSK9 inhibitors vary, and these differences will have an impact on the dosing regimens favored for these agents. For example, peak exposure of alirocumab was achieved within a median of ∼3–7 days (depending on the site of administration), and the elimination half‐life was 6–7 days following a single s.c. dose of 75 mg in a population of healthy subjects.19 In comparison, a therapeutic dose of evolocumab (s.c. 140 mg) achieves peak exposure more quickly than alirocumab (within ∼3–4 days), but has a longer elimination half‐life than that of alirocumab of 2.5–11.5 days, depending on dosing regimen.20, 21 RN317 administered s.c. achieved Cmax within a similar time‐frame to these other anti‐PCSK9 mAbs (∼3–10 days with s.c. administration), and was comparable with bococizumab for the same route of administration. However, RN317 was engineered to have a longer half‐life, and as such t1/2 was 19–21 days across the dose range, which resulted in greater exposure compared with bococizumab. Moreover, following multiple‐dose administration of RN317, no apparent “saw‐tooth” profile of LDL‐C response was noted and the trough‐to‐nadir ratio was > 0.9 throughout the study period. This may be of clinical relevance given that visit‐to‐visit variation in LDL‐C has recently been identified as an independent predictor of future CV risk.15

Although the engineering of RN317 produced the desired modifications in the pharmacokinetic profile compared with bococizumab, the LDL‐C reductions observed following either the s.c. or i.v. administration of RN317 were lower than those with equivalent doses of bococizumab. Furthermore, the mean percent reduction from baseline in LDL‐C observed with RN317 was also not as marked as that observed with other anti‐PCSK9 antibodies following single or multiple doses.11, 12, 14, 22, 23 For example, in phase II studies of alirocumab and evolocumab mean reductions from baseline in LDL‐C of up to 61% and 81%, respectively, were reported.22, 24 Mean percentage reductions from baseline of up to 84% were reported in a phase I study of bococizumab.10 The lower mean percent reduction from baseline in LDL‐C for RN317 compared with bococizumab was possibly due to the affinity for human PCSK9 being much higher for bococizumab than for RN317 as detailed above.8, 17

RN317 was well tolerated, with no treatment‐related AEs resulting in a subject discontinuing the study, and no SAEs considered treatment‐related. Furthermore, just one subject discontinued the study because of an AE. The overall incidence of AEs and the safety profile of RN317 was comparable with that known for other agents in this drug class.7, 11, 25, 26 Indeed, the most frequently occurring AEs for RN317 and bococizumab were similar to those experienced in phase I clinical trials for other monoclonal PCSK9 antibodies. For example, in a phase I trial of evolocumab the most common AE was nasopharyngitis,22 whereas headache was the most frequently occurring AE in a phase I study of alirocumab.24 The consistency in safety profile between RN317 and other monoclonal anti‐PCSK9 antibodies suggests that despite engineering the mAb to have pH‐specific binding and prolonged exposure, this did not significantly alter the tolerability profile of the drug.

In summary, this phase I multiarm study demonstrated that RN317—a pH‐sensitive, humanized IgG2Δa mAb—administered as single s.c. and i.v. doses up to 6 mg/kg and multiple s.c. doses of 300 mg Q28d was safe and well tolerated in subjects with a diagnosis of hypercholesterolemia receiving ongoing treatment with statins. RN317 was engineered to eliminate target‐mediated drug clearance, and the half‐life was longer and the duration of LDL‐C lowering longer than that of other agents in this class. RN317 producing sustained lowering of LDL‐C of ∼50% following multiple s.c. doses.

Supporting information

Additional supporting information may be found online in the supporting information tab for this article

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the clinical site investigators, participating subjects, and the Pfizer Operations Group for their assistance in conducting the study. A full list of clinical sites and investigators is provided in the Supplementary Information. This study was funded by Pfizer. Medical writing support for the development of this article was provided by Paul Oakley and Karen Burrows of Engage Scientific and was funded by Pfizer.

Author Contributions

P.D.G., M.L., T.J., H.W., H.L., P.F., and B.G. wrote the article; P.D.G., M.L., T.J., H.W., H.L., P.F., and B.G. designed the study; P.D.G., M.L., T.J., H.W., H.L., P.F., and B.G. conducted the study; M.L., T.J., and B.G. analyzed the data.

Conflict of Interest

All authors are employees of Pfizer or were employees of Pfizer when this study was conducted.

Trial Registration Number: NCT01720537

References

- 1. Basak, A. Inhibitors of proprotein convertases. J Mol. Med. (Berl). 11, 844–855 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Horton, J.D. , Cohen, J.C. & Hobbs, H.H. Molecular biology of PCSK9: its role in LDL metabolism. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2, 71–77 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lambert, G. Unravelling the functional significance of PCSK9. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 3, 304–309 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Stone, N.J. et al 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 129, S1–S45 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cohen, J.C. , Boerwinkle, E. , Mosley, T.H., Jr. & Hobbs, H.H. Sequence variations in PCSK9, low LDL, and protection against coronary heart disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 12, 1264–1272 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Abifadel, M. et al Mutations in PCSK9 cause autosomal dominant hypercholesterolemia. Nat. Genet. 2, 154–156 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dadu, R.T. & Ballantyne, C.M. Lipid lowering with PCSK9 inhibitors. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 10, 563–575 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Liang, H. et al Proprotein convertase substilisin/kexin type 9 antagonism reduces low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol in statin‐treated hypercholesterolemic nonhuman primates. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2, 228–236 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gumbiner, B. et al Effects of 12 weeks of treatment with RN316 (PF‐04950615), a humanized IgG2(δ)a monoclonal antibody binding proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin type 9, in hypercholesterolemic subjects on high and maximal dose statins. Circulation. 126, 2782 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gumbiner, B. et al The effects of single dose administration of RN316 (PF‐04950615), a humanized IgG2a monoclonal antibody binding proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin type 9, in hypercholesterolemic subjects treated with and without atorvastatin. Circulation 126(Suppl 21), A13322 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ballantyne, C.M. et al Results of bococizumab, a monoclonal antibody against proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9, from a randomized, placebo‐controlled, dose‐ranging study in statin‐treated subjects with hypercholesterolemia. Am. J. Cardiol. 9, 1212–1221 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. McKenney, J.M. et al Safety and efficacy of a monoclonal antibody to proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 serine protease, SAR236553/REGN727, in patients with primary hypercholesterolemia receiving ongoing stable atorvastatin therapy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 25, 2344–2353 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Koren, M.J. et al Efficacy and safety of longer‐term administration of evolocumab (AMG 145) in patients with hypercholesterolemia: 52‐week results from the Open‐Label Study of Long‐Term Evaluation Against LDL‐C (OSLER) randomized trial. Circulation. 2, 234–243 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Giugliano, R.P. et al Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of a monoclonal antibody to proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 in combination with a statin in patients with hypercholesterolaemia (LAPLACE‐TIMI 57): a randomised, placebo‐controlled, dose‐ranging, phase 2 study. Lancet. 9858, 2007–2017 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bangalore, S. , Breazna, A. , DeMicco, D.A. , Wun, C.C. & Messerli, F.H. Visit‐to‐visit low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol variability and risk of cardiovascular outcomes: insights from the TNT trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 15, 1539–1548 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rothwell, P.M. et al Prognostic significance of visit‐to‐visit variability, maximum systolic blood pressure, and episodic hypertension. Lancet. 9718, 895–905 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chaparro‐Riggers, J. et al Increasing serum half‐life and extending cholesterol lowering in vivo by engineering antibody with pH‐sensitive binding to PCSK9. J. Biol. Chem. 14, 11090–11097 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Udata, C. et al A mechanism‐based pharmacokinetic‐pharmacodynamic model for RN316 (PF‐04950615), a humanized mab against proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9), and its application in early clinical development. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. S51–S52 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lunven, C. et al A randomized study of the relative pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and safety of alirocumab, a fully human monoclonal antibody to PCSK9, after single subcutaneous administration at three different injection sites in healthy subjects. Cardiovasc. Ther. 6, 297–301 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Manolis, A.S. , Manolis, T.A. & Melita, H. Novel hypolipidemic agents: focus on PCSK9 inhibitors. Hosp. Chron. 1, 3–10 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 21. Langslet, G. , Emery, M. & Wasserman, S.M. Evolocumab (AMG 145) for primary hypercholesterolemia. Expert Rev. Cardiovasc. Ther. 5, 477–488 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dias, C.S. et al Effects of AMG 145 on low‐density lipoprotein cholesterol levels: results from 2 randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, ascending‐dose phase 1 studies in healthy volunteers and hypercholesterolemic subjects on statins. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 19, 1888–1898 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Koren, M.J. et al Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of a monoclonal antibody to proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 as monotherapy in patients with hypercholesterolaemia (MENDEL): a randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, phase 2 study. Lancet. 9858, 1995–2006 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Stein, E.A. et al Effect of a monoclonal antibody to PCSK9 on LDL cholesterol. N. Engl. J. Med. 12, 1108–1118 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Raal, F.J. et al PCSK9 inhibition with evolocumab (AMG 145) in heterozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia (RUTHERFORD‐2): a randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Lancet. 9965, 331–340 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Blom, D.J. et al A 52‐week placebo‐controlled trial of evolocumab in hyperlipidemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 19, 1809–1819 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional supporting information may be found online in the supporting information tab for this article

Supplementary Information