Abstract

Objectives:

Antimicrobials are frequently used in tertiary care hospitals. We conducted an observational study on children admitted to a teaching hospital in Eastern India, to generate a profile of antimicrobial use and suspected adverse drug reactions (ADRs) attributable to them.

Materials and Methods:

Hospitalized children of either sex, aged between 1 month and 12 years, were studied. Baseline demographic and clinical features, duration of hospital stay, antimicrobials received in hospital along with dosing and indications and details of suspected ADRs attributable to their use were recorded. Every patient was followed up till discharge, admission to the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit, or death.

Results:

Over the 1 year study period, 332 admissions were screened. The prevalence of antimicrobial use was 79.82%. The majority of the 265 children who received antimicrobials were males (61.10%) and hailed from rural and low socioeconomic background. Median age was 36 months. Six children died, 43 were transferred out, and the rest discharged. In most instances, either 2 (40%) or a single antibiotic (39.6%) was used. Ceftriaxone, co-amoxiclav, amikacin, vancomycin, and ampicillin were predominantly used. Antivirals, antimalarials, and antiprotozoals were used occasionally. Average number of antimicrobials per patient was 2.0 ± 1.27; the majority (84.1%) were by parenteral route and initial choice was usually empirical. Prescriptions were usually in generic name. The antimicrobial treatment ranged between 1 and 34 days, with a median of 7 days. Six ADRs were noted of which half were skin rash and the rest loose stools.

Conclusions:

The profile of antimicrobial use is broadly similar to earlier Indian studies. Apparent overuse of multiple antimicrobials per prescription and the parenteral route requires exploration. Antimicrobials are being used empirically in the absence of policy. ADRs to antimicrobials are occasional and usually mild. The baseline data can serve in situation analysis for antibiotic prescribing guidelines.

Key words: Antibiotic, antimicrobial, children, drug use survey, hospital

Infectious diseases represent a major cause of morbidity and mortality in India and are responsible for a large proportion of hospital admissions, particularly in children. Antibiotics and other antimicrobials, therefore, constitute an important category of drugs, both in the community and in hospitals. There is considerable evidence linking indiscriminate use of antimicrobials to altered susceptibility patterns among infectious organisms and often frank resistance.[1] We face huge challenges in rational use of antimicrobials starting with general lack of awareness and unsatisfactory levels of personal hygiene and environmental sanitation to lack of surveillance mechanisms for monitoring antimicrobial use and resistance, mostly empirical use of antibiotics due to dearth of microbiology laboratory support, absence of or ineffective antibiotic use policies in most healthcare settings and nonhuman use of antimicrobials.[2,3,4] The nature and pattern of antimicrobial prescribing changes with time as spectrum of pathogens change and new antimicrobials are introduced. In India, antimicrobials may account for 50% of total value of drugs sold, but the prevalence of antimicrobial use has varied across surveys.[5] With widespread use of antibiotics, the prevalence of resistance also increases. The association of resistance with the use of antimicrobials agents has been documented in both in- and out-patient settings.[6,7] The occurrence of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) is another problem with antimicrobial use. ADRs in pediatric population may have relatively more severe effect than adults leading to significant morbidity among children.[8] A systematic review published some time back reported the incidence of pediatric ADRs at 9.5%, responsible for 2.1% of hospital admissions, with 39.3% of them being life-threatening.[9] A study of ADR burden in children in Southern India found that ADRs occurred more among infants and antibiotics were commonly implicated.[10]

Rational use of antimicrobials in the long run, therefore, demands continuous survey of antimicrobial use and related ADR monitoring.[11] Patterns of use in children need to be studied separately as they will vary from use in adults. However, there is limited data in this respect from India and no recent data from the Eastern region. With this background, we planned to observe antimicrobial use in pediatric medicine ward of our tertiary care hospital to generate data regarding antimicrobial utilization and related ADRs.

Materials and Methods

The observational study was carried out among indoor patients admitted to the pediatric medicine ward of a tertiary care teaching hospital. This is a government hospital catering to the city and at least 10 adjoining districts. The Pediatrics Medicine Department admits 10–12 patients daily on an average. Institutional Ethics Committee approval was obtained beforehand. Written informed consent was obtained from a parent or legal guardian, with the provision of a witness when the guardian was illiterate.

Subjects of either sex and age between 1 month and 12 years were recruited into the study over 12 months (May 2013 to April 2014) if their in-house prescriptions contained antimicrobial agents. Seriously ill children were excluded. Sampling was purposive. Recruitment was done in 1–2 days per week and every effort was made to recruit all children admitted on a study day if they satisfied inclusion criteria. The recruitment days corresponded to the fixed admission days of the pediatrician investigator, and once recruited the child was followed up till discharge, shifting to the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU), or death. Although the recruitment of new subjects was done on fixed days of the week, the researchers visited the wards as often as required to keep complete track of the medication being used by every recruited subject.

Antimicrobials are supplied free in the hospital. Our operational definition of antimicrobial agent included synthetic as well as naturally obtained drugs that attenuate microorganisms, thereby covering all antibacterial, antifungal, antiviral, and antiprotozoals agents. Baseline demographic and clinical features, duration of hospital stay, antimicrobials received in the hospital along with dosing and indication and details of suspected ADRs attributable to their use were recorded. Data were captured on a structured case report form. ADR data were captured on the ADR monitoring form of Pharmacovigilance Programme of India (PvPI).[11] Casualty assessment was done on the basis of the World Health Organization and Uppsala Monitoring Center criteria.[12] Parents of the children were interviewed regarding their residential, literacy, and socio-economic status and the diagnosis or complaints on the basis of which the admission took place.

The data have been summarized by routine descriptive statistics, namely mean and standard deviation for numerical variables, additionally median and interquartile range for skewed variables and counts and percentages for categorical variables. The 95% confidence interval (CI) has been presented for key figures. GraphPad Prism version 5, 2007, (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, California, USA) software was used for analysis.

Results

During the 1 year study, a total of 265 patients admitted to the pediatric medicine ward were recruited. These 265 came from 332 eligible subjects; that is patients admitted to the pediatric ward on the study days if they consented to be part of the study. Of them, 67 were not given antimicrobial prescriptions. Thus, the prevalence of antimicrobial use was 79.82% (95% CI 75.50%–84.14%).

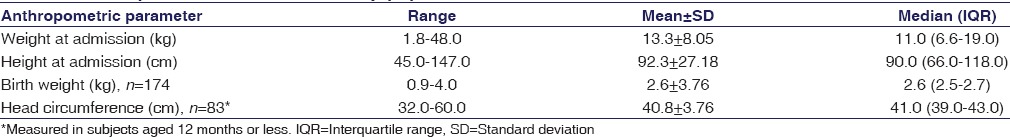

Among these 265 children, 162 (61.10%) were males. The majority of the children belonged to the preschool age group, with the median age at 36.0 (interquartile range 8.5–96.0) months. Subjects were mostly from rural (59.20%) and low socioeconomic background. The family background was evenly distributed between nuclear and joint families. Patients admitted were from different districts of West Bengal and also from outside the state, but the highest numbers were from Kolkata and the two adjoining districts of South 24 Parganas and Howrah – 10.9%, 21.1%, and 10.9%, respectively. The majority of the parents were educated up to the primary or secondary levels. The father was the major, if not the sole, earning member for the majority of the families and was mostly engaged in nonskilled occupations. The anthropometric data are summarized in Table 1 and indicates that the children were of average height and weight in consonance with their age.

Table 1.

Anthropometric data for the study population

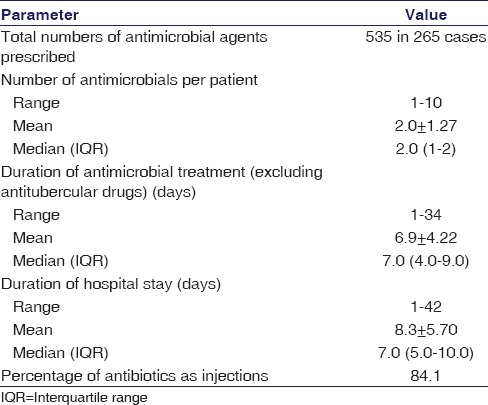

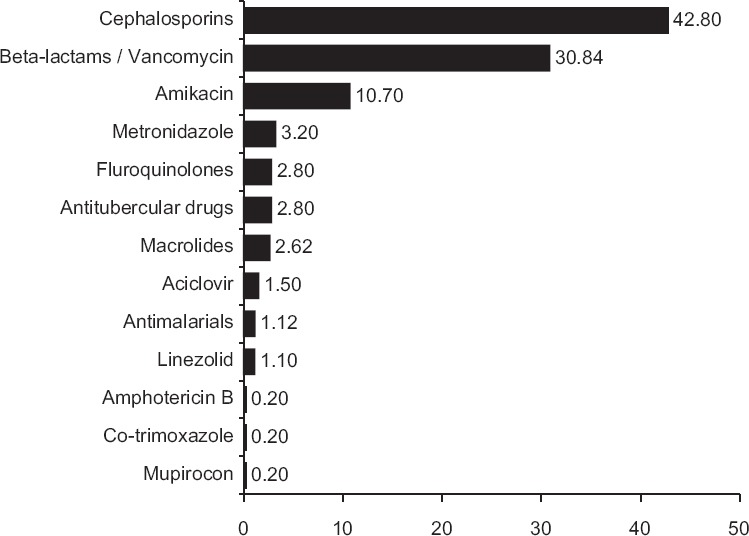

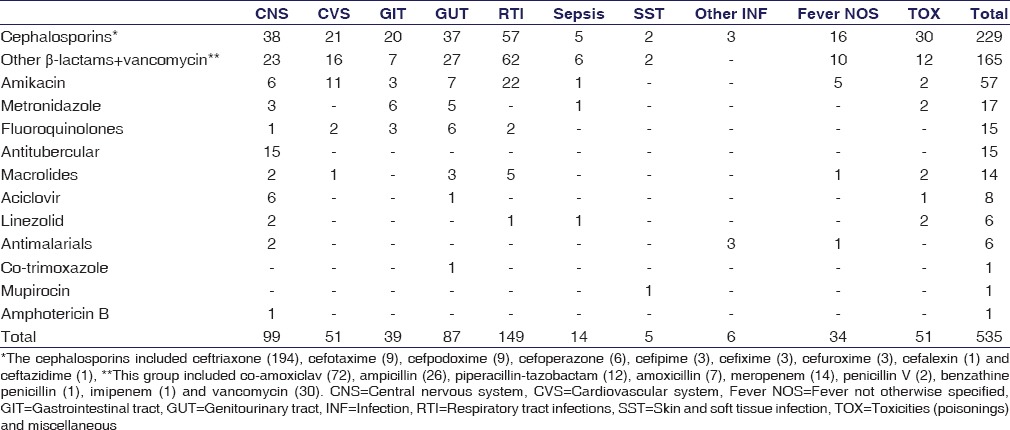

Over the 1 year study, the total number of antimicrobial agents prescribed to the 265 children was 535. Table 2 provides a snapshot of this antimicrobial use. The highest number of antimicrobial prescriptions were from the cephalosporin class (229; 42.80%) while co-trimoxazole, amphotericin B and mupirocin (0.2% each) were used sparingly. Ceftriaxone was the single most frequently prescribed drug (36.3%). Among the 229 instances of cephalosporin use, the highest prescribed was ceftriaxone (194; 84.71%) whereas cefalexin (0.2%) and ceftazidime (0.2%) were used the least. The majority of the cephalosporins were prescribed for respiratory tract infections (57; 24.89%) and the least for soft tissue infections (2; 0.87%). Penicillins, other β-lactams, and vancomycin accounted for 165 (30.84%) instances. Co-amoxiclav (13.5%) and ampicillin (4.9%) were prescribed more frequently, wereas benzathine penicillin and imipenem (0.2% each) were used sparingly. Highest numbers in this group were prescribed for respiratory tract infections (37.57%) and the lowest for skin and soft tissue infections (1.21%). Figure 1 and Table 3 provide a system-wise break-up of the 535 instances of antimicrobial use.

Table 2.

Snapshot of antimicrobial use in study subjects

Figure 1.

Percentage frequency of use of individual groups of antimicrobials in 265 children (n = 535)

Table 3.

System-wise breakup of individual antimicrobial use in 265 children

Overall, the highest numbers of antimicrobial agents were prescribed for respiratory tract infections (149, 27.85%) followed by infections involving the central nervous system (CNS) (99, 18.50%) and the genitourinary tract (87, 16.26%). Among the total number of antimicrobial prescriptions for respiratory tract infections; the highest numbers were prescribed from other β-lactam group followed by cephalosporins and aminoglycosides. For CNS infections, highest numbers were prescribed from cephalosporin class followed by other β-lactams and antitubercular drugs. For fever without specification of cause, antimicrobials prescribed (6.35%) included cephalosporins, other β-lactams, and amikacin.

It was found that 105 (39.62%) prescriptions contained a single antimicrobial agent, 106 (40%) contained two and 54 (20.38%) contained either three or more than three antimicrobial agents. In one instance, total 10 agents were prescribed during the period of hospital stay.

Analyzing the dosage forms used, it was observed that the majority (450; 84.1%) of the antimicrobials were administered intravenously and the rest by oral route (84; 15.7%). Only mupirocin was used topically. The great majority (528; 98.69%) were prescribed in generic name. The 7 brand name prescriptions included ATD combinations, piperacillin-tazobactam, and ceftriaxone in a single instance.

In most children (85.66%) antimicrobial therapy was empirical and based on clinical judgment. In 14.34% cases, treatment was guided by results of laboratory tests, including 23 (8.7%) instances of blood culture and 13 (4.9%) of cerebrospinal fluid examination. Peripheral blood smears were examined in suspected malaria cases. Only 8 specimens out of 23 sent for blood culture showed positive results, with Staphylococcus aureus isolated in five.

ADRs, of at least “possible” causality, were noted in 6 (2.26%) children, of which half were cutaneous reactions and the rest loose stools. Vancomycin was responsible for skin rash in 3 cases, while ampicillin was responsible for loose stool in 2 cases and amoxicillin in 1 case. Although the reactions were not deemed to be serious, vancomycin was replaced by suitable alternatives in the skin rash cases.

Out of 265 patients studied most were either discharged (216; 81.51%) or shifted to the PICU (43; 16.23%). However, six babies (2.26%) in the study cohort died from their illness. ADRs were not implicated in any of the instances of death or worsening of disease.

Discussion

Antimicrobial use is frequent in indoor patients of hospitals, particularly tertiary care hospitals that act as referral centers, and particularly so in pediatric wards. In a nation-wide point prevalence study in pediatric in-patients across 8 children hospitals in Australia,[13] the authors reported that of 1373 patients, 631 (46%) were prescribed at least one antimicrobial agent, 198 (31%) of whom were <1-year-old. In our case, the prevalence was nearly 80% with the majority of children within 4 years of age.

In this study, around 60% of the subjects were male and 60% hailed from rural areas. These demographic figures are broadly similar to reports from public hospitals in other developing countries, such as Ethiopia[14] and Nepal.[15] The most common indication for antimicrobial use in our series was pneumonia (10.2%), followed by other lower respiratory tract infections (9.4%). Among the antimicrobials prescribed for respiratory tract infections; the majority were cephalosporins or other β-lactams followed by vancomycin and amikacin. A study from Gujarat[5] showed that highest numbers of antimicrobial agents were prescribed for respiratory tract infections and highest numbers were prescribed from β-lactam and aminoglycosides groups. A study carried out in Kathmandu Valley, Nepal,[15] also observed that pneumonia was the most common diagnosis for in-hospital antimicrobial use.

In this study, cephalosporins (42.80%) were most commonly prescribed antimicrobials followed by other members of the β-lactam class and aminoglycosides. Ceftriaxone (36.3%), co-amoxiclav (13.5%) and amikacin (10.7%) were most frequently prescribed. The Kathmandu Valley study[15] reported that cephalosporins were the most commonly prescribed antimicrobials followed by penicillins. Among cephalosporins, ceftriaxone was frequently prescribed. A study carried out in a tertiary hospital in Bangladesh reported that ampicillin, gentamicin, amoxicillin, cloxacillin and ceftriaxone were prescribed frequently.[16] A similar study carried out in Eastern Nepal reported that gentamicin, ampicillin, crystalline penicillin, and cefotaxime were the most commonly prescribed antibiotics.[17] A study in Chandigarh by Sharma et al.[18] showed that aminoglycosides (amikacin), cephalosporins (cefotaxime), quinolones (ciprofloxacin), and cloxacillin were most frequently prescribed. Deshmukh et al.[19] reported from rural Maharashtra that most commonly prescribed antimicrobial agent was cefotaxime (21.7%) in medicine and metronidazole in surgery (30.6%) wards. Thus, so far as the pattern of antimicrobial use is concerned, our experience broadly conforms to that of other authors reporting prescribing trends for indoor patients in similar socio-economic settings. It is noteworthy that our hospital does not have a standing infection control committee or antimicrobial use policy that would have constrained choice of drugs.

Percentage of encounters with an antibiotic prescribed (nearly 80% in our case) and average number of antibiotics per prescription have been considered as important indicators for rational use of medicines in out-patient primary care.[20] To minimize the risk of drug-drug interactions, development of bacterial resistance and costs, it is preferable to keep the number of drugs per prescription as low as possible. In our study, around 60% prescriptions contained either two or more than two antimicrobials, with the median number at two. Prajapati and Bhatt.[5] reported that mean number of drugs per prescription was 1.97 and number of prescriptions with two or more antimicrobial agents was around 71%. Sharma et al.[18] observed that prescribing of two antimicrobials was common (around 60%) in pediatric cases. However, the study carried out in Kathmandu Valley[15] reported that the major fraction (93%) of patients was prescribed one antibiotic. Thus, prima facie the situation in India, and particularly in our setting, offers scope for improvement.

We found that 84.1% antimicrobial agents were prescribed by parenteral routes, while only 15.7% were for oral use; 98.7% were prescribed in generic name. Prajapati and Bhatt.[5] documented that 86.8% antimicrobial agents were for parenteral administration, whereas only 13.2% were for oral use; 83.5% drugs were prescribed in generic name. The predominance of parenteral administration can be explained in the context of indoor patients who are likely to be more seriously ill than patients who can be managed on ambulatory basis. Still the figure for injections appears to be high and calls for investigation through prescription audit and formulation of antibiotic guidelines. Similar concerns have been voiced in a recent Latvian study on antimicrobial usage among hospitalized children, including neonates.[21] The near 100% generic prescribing is a desirable situation. We feel that this owes to a large extent on local government policy that seeks to enforce generic prescribing in public hospitals.

Ideally, in any large hospital, antibiotic prescribing should be governed by appropriate guidelines supported by antimicrobial resistance surveillance. Unfortunately, our institution currently does not have an active surveillance program or updated guidelines. In the great majority of instances, initial drug choice was empirical and antimicrobial treatment was guided by the results of laboratory tests in just 14.3% cases; which is far from satisfactory. Furthermore, the low yield of culture tests, as noted in our case, often frustrate clinicians. The same situation seems to be prevailing in the settings for earlier studies.[15] This is a grossly undesirable situation since antibiotic use guidelines supported through appropriate surveillance is regarded as a fundamental prerequisite for rational antibiotic use.[22] This is also a felt need for physicians in India.[3] In the face of ongoing spread of antimicrobial resistance coupled with declining rate of new antimicrobial development, a lot of emphasis is being accorded of late to antibiotic stewardship programs (ASPs) in hospitals.[23] However, although ASPs can be effective in improving the quality and safety of antimicrobial prescribing for hospitalized patients, there are unique issues relevant to children and pediatric ASPs are still in their infancy.[24]

In our study, suspected ADRs were noted in only 2.26% cases and were predominantly cutaneous reactions or loose stool. Thus, the ADR burden was quite manageable. Priyadharsini et al.,[10] in their study on ADRs in pediatric patients reported that antibiotics were responsible for a large share of the burden and urticaria and other rashes were the most common ADRs attributable to antibiotics. The hospital being part of an ADR Monitoring Center under PvPI, these reports were duly submitted to PvPI. However, as yet there have no feedback sessions in this regard for the physicians concerned.

The present study has its share of limitations. For logistical reasons, subject recruitment was not done on a continuous basis and sampling was purposive rather than random. However, the prospective data collection has ensured that for subjects recruited we have reliable data. Neonates and PICU patients were not a part of the study, but drug use patterns in such children also need to be addressed.

Nevertheless, in conclusion, we can say that this study profiles antimicrobial use in hospitalized children in our institution and the situation is likely to be representative of other public hospitals catering to poor patients. Use of well-known antimicrobials and generic prescribing are satisfactory trends noted. On the flip side, multiple antibiotics in the same patient and commonplace use of injections are matters of concern. Furthermore, choice of antimicrobial being mostly empirical there may be a tendency to use more expensive cephalosporins in lieu of less expensive drugs. We hope that these findings can be utilized in conjunction with antimicrobial resistance surveillance data in formulating antibiotic use guidelines for pediatric wards. Drug use surveys in other settings such as pediatric OPD and PICU are needed before venturing into the development of comprehensive pediatric antimicrobial use guidelines.

Financial Support and Sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the junior residents of the Department of Pediatrics, Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education & Research, Kolkata for their assistance in data collection.

References

- 1.Chandy SJ, Thomas K, Mathai E, Antonisamy B, Holloway KA, Stalsby Lundborg C. Patterns of antibiotic use in the community and challenges of antibiotic surveillance in a lower-middle-income country setting: A repeated cross-sectional study in Vellore, South India. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68:229–36. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wattal C, Goel N. Tackling antibiotic resistance in India. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2014;12:1427–40. doi: 10.1586/14787210.2014.976612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chatterjee D, Sen S, Begum SA, Adhikari A, Hazra A, Das AK. A questionnaire-based survey to ascertain the views of clinicians regarding rational use of antibiotics in teaching hospitals of Kolkata. Indian J Pharmacol. 2015;47:105–8. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.150373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kanungo S, Mahapatra T, Bhaduri B, Mahapatra S, Chakraborty ND, Manna B, et al. Diarrhoea-related knowledge and practice of physicians in urban slums of Kolkata, India. Epidemiol Infect. 2014;142:314–26. doi: 10.1017/S0950268813001076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prajapati V, Bhatt JD. Study of prescribing pattern of antimicrobial agents in the pediatric wards at tertiary teaching care hospital, Gujarat. Indian J Pharm Sci Res. 2012;3:2348–55. [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGowan JE., Jr Antimicrobial resistance in hospital organisms and its relation to antibiotic use. Rev Infect Dis. 1983;5:1033–48. doi: 10.1093/clinids/5.6.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reichler MR, Allphin AA, Breiman RF, Schreiber JR, Arnold JE, McDougal LK, et al. The spread of multiply resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae at a day care center in Ohio. J Infect Dis. 1992;166:1346–53. doi: 10.1093/infdis/166.6.1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aagaard L, Hansen EH. Adverse drug reactions reported for systemic antibacterials in Danish children over a decade. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;70:765–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03732.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Impicciatore P, Choonara I, Clarkson A, Provasi D, Pandolfini C, Bonati M. Incidence of adverse drug reactions in paediatric in/out-patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2001;52:77–83. doi: 10.1046/j.0306-5251.2001.01407.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Priyadharsini R, Surendiran A, Adithan C, Sreenivasan S, Sahoo FK. A study of adverse drug reactions in pediatric patients. J Pharmacol Pharmacother. 2011;2:277–80. doi: 10.4103/0976-500X.85957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pharmacovigilance Programme of India. Suspected Adverse drug Reaction Reporting Form. [Last accessed on 2013 Apr 20]. Available from: http://www.ipc.gov.in/PvPI/ADRReportingForm.pdf .

- 12.Zaki SA. Adverse drug reaction and causality assessment scales. Lung India. 2011;28:152–3. doi: 10.4103/0970-2113.80343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Osowicki J, Gwee A, Noronha J, Palasanthiran P, McMullan B, Britton PN, et al. Australia-wide point prevalence survey of the use and appropriateness of antimicrobial prescribing for children in hospital. Med J Aust. 2014;201:657–62. doi: 10.5694/mja13.00154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woldu MA, Suleman S, Workneh N, Berhane H. Retrospective study of the pattern of antibiotic use in Hawassa University Referral Hospital Pediatric Ward, Southern Ethiopia. J Appl Pharm Sci. 2013;3:93–8. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Palikhe N. Prescribing pattern of antibiotics in pediatric hospital of Kathmandu Valley. J Nepal Health Counc. 2004;2:31–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akter FU, Heller D, Smith A, Rahman MM, Milly AF. Antimicrobial use in paediatric wards of teaching hospital in Bangladesh. Mymensingh Med J. 2004;13:63–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rauniar GP, Naga Rani MA, Das BP. Prescribing pattern of antimicrobial agents in paediatric in-patients. J Nepalgunj Med Coll. 2000;3:34–7. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharma D, Reeta K, Badyal DK, Garg SK, Bhargava VK. Antimicrobial prescribing pattern in an Indian tertiary hospital. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 1998;42:533–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deshmukh V, Khadke V, Patil A, Lohar P. Study of prescribing pattern of antimicrobial agents in indoor patients of a tertiary care hospital. Int J Basic Clin Pharmacol. 2013;2:281–5. [Google Scholar]

- 20.How to Investigate drug Use in Health Facilities: Selected drug Use Indicators. Geneva: WHO; 1993. World Health Organization Action Programme on Essential Drugs. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sviestina I, Mozgis D. Antimicrobial usage among hospitalized children in Latvia: A neonatal and pediatric antimicrobial point prevalence survey. Medicina (Kaunas) 2014;50:175–81. doi: 10.1016/j.medici.2014.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Versporten A, Sharland M, Bielicki J, Drapier N, Vankerckhoven V, Goossens H. ARPEC Project Group Members. The antibiotic resistance and prescribing in European Children project: A neonatal and pediatric antimicrobial web-based point prevalence survey in 73 hospitals worldwide. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32:e242–53. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318286c612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walia K, Ohri VC, Mathai D. Antimicrobial Stewardship Programme of ICMR. Antimicrobial Stewardship Programme (AMSP) practices in India. Indian J Med Res. 2015;142:130–8. doi: 10.4103/0971-5916.164228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Newland JG, Banerjee R, Gerber JS, Hersh AL, Steinke L, Weissman SJ. Antimicrobial stewardship in pediatric care: Strategies and future directions. Pharmacotherapy. 2012;32:735–43. doi: 10.1002/j.1875-9114.2012.01155.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]