Abstract

Drug-induced leukocytoclastic vasculitis is a small-vessel vasculitis that most commonly manifests with palpable purpuric lesions on gravity-dependent areas. Vasculitis occurs within weeks after initial administration of medication and demonstrates clearance upon withdrawal of medication. Levetiracetam, a pyrrolidone derivative, is used as an adjunctive therapy in patients with refractory focal epilepsy, myoclonic epilepsy, and primary generalized tonic–clonic seizures. We present a case of a 14-year-old female, who developed cutaneous small-vessel vasculitis within 8 days of initiation of levetiracetam. Vasculitis was successfully managed by discontinuation of medication and systemic corticosteroids. This adverse reaction, to the best of our knowledge, has not been previously reported in literature.

Key words: Cutaneous small-vessel vasculitis, drug-induced leukocytoclastic vasculitis, immune complex, levetiracetam

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV), also known as hypersensitivity vasculitis, is a small-vessel vasculitis caused by deposition of immune complexes with subsequent activation of complement system leading to vascular injury and extravasation of erythrocytes.[1] LCV has multiple etiologies with about 50% cases being “idiopathic” while 15%–20% are due to infections and another 15%–20% are related to inflammatory diseases such as collagen vascular disorders. Approximately, 10%–15% cases are due to medications and other drugs, and <5% cases are associated with malignancy.[1,2] Clinically, it manifests as purpura, urticaria, or ulcers on gravity-dependent body parts.

Many drugs can cause LCV, most common ones being penicillins, sulfonamides, quinolones, analgesics, thiazides and other diuretics, anticonvulsants, phenothiazines, allopurinol, and colony-stimulating factors.[3] We present a case of 14-year-old female, who developed LCV within 8 days of initiation of levetiracetam.

Case Report

A 14-year-old female patient presented to us with complaints of palpable purpura and ulceration over lower extremities for last 5 days. The patient was receiving anticonvulsive therapy (phenytoin) for epilepsy since she was 3 years old. A fortnight ago, her neurologist added levetiracetam 500 mg daily to phenytoin 50 mg thrice daily, owing to worsening of epilepsy symptoms. Eight days after initiation of levetiracetam, the patient developed palpable purpura over lower extremities, associated with itching. This progressed to form large necrotic eschars and painful ulcers over next 3 days. She did not suffer from any preceding infection or illnesses and demonstrated the absence of systemic manifestations such as arthralgias, hematuria, melena, or abdominal pain. Cutaneous examination revealed the presence of palpable purpura and large ulcers covered with necrotic eschars over the lower extremities [Figure 1]. Her vital parameters were within normal range and systemic examination revealed no abnormality.

Figure 1.

Palpable purpura and necrotic ulcers over lower extremities

Routine laboratory investigations were detected to be normal. Complete hemogram ruled out the presence of eosinophilia. Platelet count and renal function tests were also within normal range. Additional investigations demonstrated a negative antinuclear antibody, cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies and normal serum protein electrophoresis, hepatitis screen, urinalysis, antidouble-stranded DNA antibody, and thyroid assay. A skin biopsy from the lesion revealed fibrinoid necrosis of walls of small vessels consistent with LCV [Figure 2]. Immunofluorescence of the biopsy specimen could not be done due to nonavailability in our setup.

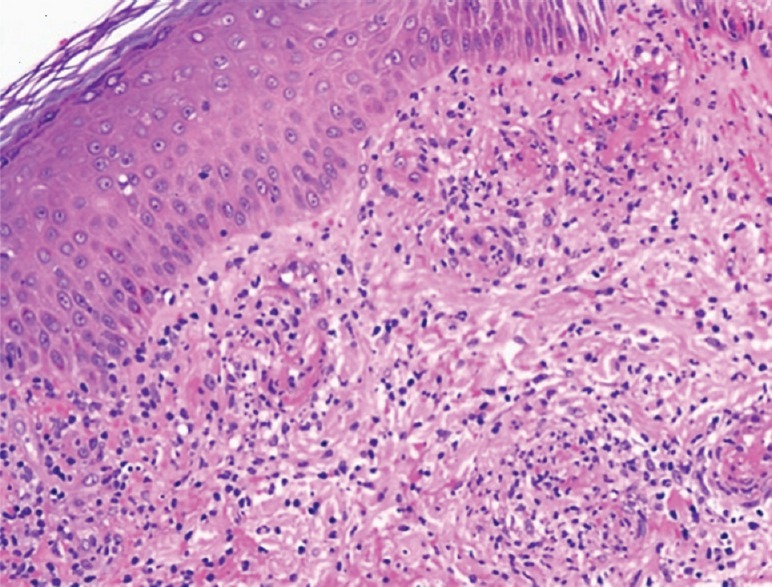

Figure 2.

Histopathological examination showing red blood cell extravasation, infiltration of neutrophils and eosinophils and fibrinoid necrosis (H and E, ×40) in the dermis

On the basis of temporal association and clinicohistopathological findings, a diagnosis of levetiracetam-induced LCV was established and levetiracetam was discontinued. Adverse reaction severity was determined as Level 4(b) according to Modified Hartwig and Siegel scale as it was the reason for admission.[4] The patient was treated with systemic corticosteroids (30 mg/day of prednisolone) along with topical corticosteroids (mometasone furoate 0.1% cream twice daily), emollients, and oral levocetirizine 5 mg twice daily. Levetiracetam was replaced with clonazepam while phenytoin was continued. After 1 week of stoppage of levetiracetam and initiation of treatment, lesions had started subsiding. Oral steroids were gradually tapered off over next 3 weeks. At 4 weeks' follow-up, lesions had cleared completely with residual hyperpigmentation and scarring. No recurrence of the eruption was observed during a 6-month follow-up period.

Causality assessment was carried out using Naranjo's scale and World Health OrganizationUppsala Monitoring Centre Criteria, which suggested that levetiracetam was the “probable” (Naranjo's score 5) cause of this adverse drug reaction.[5,6]

Discussion

Drugs can cause vasculitis of various morphological types. Most commonly, these cause a superficial small vessel cutaneous LCV; however, other patterns including systemic vasculitis also occur. More than 100 drugs are implicated as causes of drug-induced vasculitis although actual frequency of drug-induced vasculitis is low. Commonly, implicated drugs include penicillins, sulfonamides, quinolones, analgesics, anticonvulsants, phenothiazines, allopurinol, and colony-stimulating factors. Less commonly used drugs with a significant risk of vasculitis include thiouracil, hydralazine, and biologicals such as adalimumab, etanercept and infliximab, ephedrine, amphetamines, vaccines (especially influenza and hepatitis B vaccines), herbal remedies, and food additives.[3,7]

Exact pathogenesis of drug-associated cutaneous vasculitis is unclear, but studies suggest that the offending drug may act as a hapten, which stimulates antibody production and immune complex formation. These immune complexes are subsequently deposited in postcapillary venules leading to complement activation and vascular damage.[8]

Cutaneous manifestations of drug-induced vasculitis include palpable purpura, papules, and bullae. Palpable purpura can occur hours to weeks following exposure to offending drug and most commonly develops on gravity-dependent areas, such as lower extremities and buttocks. This was also observed in the present case where lesions started appearing after 8 days of initiation of offending drug and were localized mostly to lower limbs. Distinguishing drug-related vasculitis from other etiologies of LCV can be difficult. However, pattern of development and resolution of lesions with continuation or discontinuation of medication can help in diagnosis.[1]

LCV is a transient vasculitis and is usually self-limiting. Treatment is often not required. Withdrawal of offending drug and minimization of stasis by compression, elevation, and use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are employed. Antihistamines and systemic corticosteroids may be required when the cutaneous lesions are progressive as in present case.[1,7]

Levetiracetam is a pyrrolidone derivative that is thought to exert its antiepileptic effects through adherence to synaptic vesicle protein SV2A and modulation of neurotransmitter release. Levetiracetam is an effective adjunctive therapy in patients with refractory focal epilepsy, myoclonic epilepsy, and primary generalized tonic–clonic seizures. Drug interactions between LEV and other medications, such as warfarin, digoxin, oral contraceptives, probenecid, and other antiseizure medications, are not reported. Levetiracetam causes several adverse neurological effects including headache, somnolence, asthenia, dizziness, irritability, and behavioral changes. In addition, it causes hematological side effects such as mild thrombocytopenia, leukopenia, and anemia.[9] Cutaneous side effects with levetiracetam are less frequent compared to other antiepileptic medication, but adverse effects such as bullous pemphigoid, maculopapular drug rash, and drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms have been reported.[10] Even though LCV is a common adverse effect of antiepileptics, but to the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported case of LCV with levetiracetam. Based on time–event relationship, morphology, distribution, histopathological findings, and rapid response on withdrawal of the drug, we conclude that patient developed LCV due to levetiracetam.

Conclusion

Even though risk of cutaneous adverse effects with levetiracetam is less, clinicians should be aware of possibility of adverse effects such as small-vessel vasculitis or drug eruption occurring as a rare adverse effect with this drug.

Financial Support and Sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Merkel PA. Drug-induced vasculitis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2001;27:849–62. doi: 10.1016/s0889-857x(05)70239-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fiorentino DF. Cutaneous vasculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:311–40. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2003.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Litt JZ. Drug Eruption Reference Manual. 12th ed. London: Taylor and Francis; 2006. pp. 655–6. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hartwig SC, Siegel J, Schneider PJ. Preventability and severity assessment in reporting adverse drug reactions. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1992;49:2229–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, Sandor P, Ruiz I, Roberts EA, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30:239–45. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1981.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Use of the WHO-UMC System for Standardized Case Causality Assessment [Monograph on the Internet] Uppsala: The Uppsala Monitoring Centre; 2005. [Last accessed on 16 Dec 29]. Available from: http://www.who-umc.org/Graphics/24734.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wiik A. Drug-induced vasculitis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2008;20:35–9. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e3282f1331f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.ten Holder SM, Joy MS, Falk RJ. Cutaneous and systemic manifestations of drug-induced vasculitis. Ann Pharmacother. 2002;36:130–47. doi: 10.1345/aph.1A124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Smedt T, Raedt R, Vonck K, Boon P. Levetiracetam: Part II, the clinical profile of a novel anticonvulsant drug. CNS Drug Rev. 2007;13:57–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-3458.2007.00005.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karadag AS, Bilgili SG, Calka O, Onder S, Kosem M, Burakgazi-Dalkilic E. A case of levetiracetam induced bullous pemphigoid. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2013;32:176–8. doi: 10.3109/15569527.2012.725444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]