Abstract

Objectives:

To assess the polypharmacy and appropriateness of prescriptions in geriatric patients in a tertiary care hospital.

Methods:

An observational study was done in geriatric patients (>60 years) of either gender. The data collected from patients included: Socio-demographic data such as age, gender, marital status, educational status, socioeconomic status, occupation, nutritional status, history of alcohol/smoking, exercise history, details of comorbid diseases, medication history, findings of clinical examination etc. In this study, polypharmacy was considered as having 5 or more medications per prescription. Medication appropriateness for each patient was analysed separately based on their medical history and clinical findings by applying medication appropriateness index, screening tool to alert to right treatment (START) and Beers criteria and STOPP criteria.

Results:

A total of 426 patients, 216 (50.7%) were males and 210 (49.3%) were females. Polypharmacy was present in 282 prescriptions (66.2%). Highest prevalence of polypharmacy was seen in 70-79 years age group compared to the other two groups and it was statistically significant. Out of 426 patients, 36 patients were receiving drugs which were to be avoided as per Beers criteria. Among the total patients, 39 patients were overprescribed as per MAI, 56 patients were under prescribed as per START criteria and 85 out of 426 prescriptions were inappropriate in accordance with beers criteria, stop criteria, start criteria and MAI index.

Conclusion:

Around 66.19% patients were receiving polypharmacy. Significant number of patients were receiving drugs which are to be avoided as well as overprescribed and under prescribed. Inappropriate prescription was seen in a good number of patients.

Key words: Beer's criteria, inappropriate prescription, polypharmacy screening tool of older person's prescriptions criteria, screening tool to alert to right treatment criteria

Appropriate prescribing is the outcome of the decision-making process that maximizes net individual health gains within the society's available resources.[1] If a drug has benefits that outweigh the risks, then the use of drug is considered appropriate.[2] The term “polypharmacy” and the phrase “inappropriate drug use” are used interchangeably, and there is no generally accepted consensus for the definition of polypharmacy. It indicates the use of multiple drugs by an individual. In this study, polypharmacy was considered if the patient receives five or more concurrent medications.[3]

Evaluation of quality of health care, especially in geriatrics, is gaining more importance in the recent years. Elderly patients are the largest consumers of medication. Nearly, 7.7% of the Indian population are geriatrics (60 years old).[4] Longer life expectancy, comorbidity, and the strict adherence to evidence-based clinical practice guidelines pave the way for polypharmacy. Prescribing cascade, i.e., medication resulting in an adverse drug reaction (ADE) that is treated with another medication could be one of the factors involved in polypharmacy.[5]

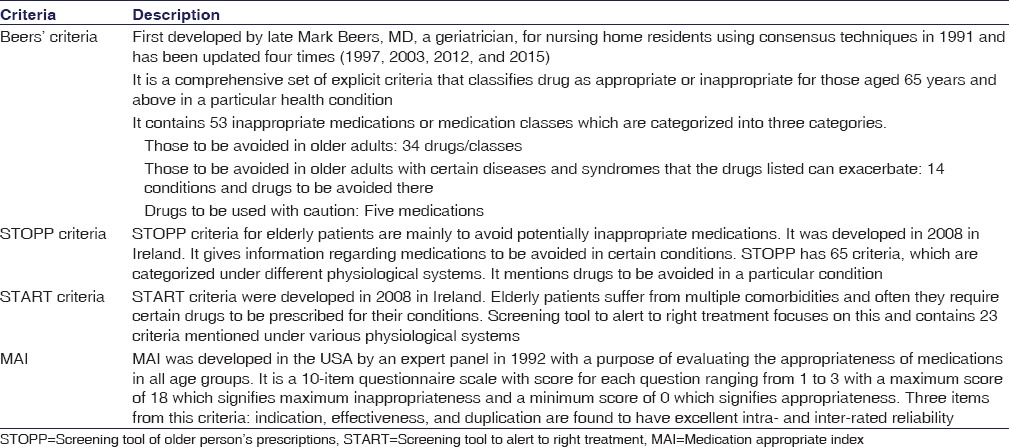

Polypharmacy in geriatrics is becoming a big problem because it is associated with greater health-care costs and substantial risk of ADEs, drug-drug interactions, medication noncompliance, decreased functional activity reduced functional capacity, and can increase the prevalence of drug associated morbidity and mortality.[6] In addition to polypharmacy, inappropriate prescribing is also a challenge. It is associated with detrimental effects on the elderly. Different tools to assess appropriateness of prescription in geriatrics include Beers criteria,[7] screening tool of older person's prescriptions (STOPP) criteria,[8] screening tool to alert to right treatment (START) criteria,[2] and medication appropriate index (MAI).[9]

In this study, we evaluated the appropriateness of prescription using all these four tools in addition to evaluating the proportion of patients receiving polypharmacy, overprescribing, and underprescribing.

Materials and Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted in the medicine outpatient department (OPD) of a tertiary care hospital in South India, during the period of January 2015 to April 2016. Both male and female patients above the age of 60 years attending medicine OPD of a tertiary care hospital were included in the study. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee. Data regarding patient's demographics and their clinical history and drug history were obtained from the patient records maintained in the OPD. We excluded vitamins and minerals, herbals, and other alternative medicines as it is difficult to analyze their appropriateness using the criteria, and we counted the remaining medications which the patient was receiving, and if five or more drugs were present, then it was considered as polypharmacy. Medication appropriateness for each patient was analyzed separately based on their medical history and clinical findings by applying MAI, Beers criteria, STOPP criteria, and START criteria [Table 1]. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (IEC Approval No. IEC KMC MLR 08-14/166 dated August 20, 2014). Patients were recruited into the study after obtaining their written informed consent.

Table 1.

Different tools to assess appropriateness of prescription in geriatric patients

Sample size was calculated based on expected proportion of people aged 60 years conceiving polypharmacy as 52% as per previous studies.[10] Taking 10% as relative precision at 90% power and confidence level of 95%, the sample size was found to be 355. Adding 20% as nonresponders, final sample size came to be 426 geriatric patients.

Statistical Analysis

Analysis was done using SPSS Inc. Released 2007. SPSS for Windows, Version 16.0. (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA). Data were summarized using descriptive statistics. Continuous variables were analyzed using Student t– tests, and categorical variables were analyzed using Chi-square test. Pearson correlation was used to correlate between different parameters.

Results

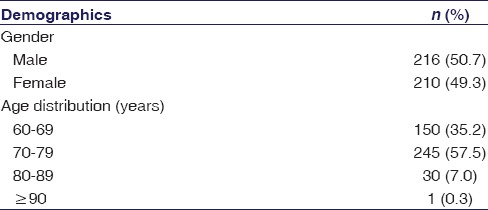

A total of 426 patients were included in the study. Among them, 216 (50.7%) were males and 210 (49.3%) were females. Mean age of the patients was 71.6 ± 6.4 years (61-91 years). Around 144 (33.8%) patients were receiving <5 medications and 282 (66.19%) patients were on five or more medications. Mean number of medications used by patients was 4.84 ± 1.945 (range 1–10). Various demographic features related to distribution of gender and age are mentioned in Table 2.

Table 2.

Gender and age distribution among the geriatric patients in the study (n=426)

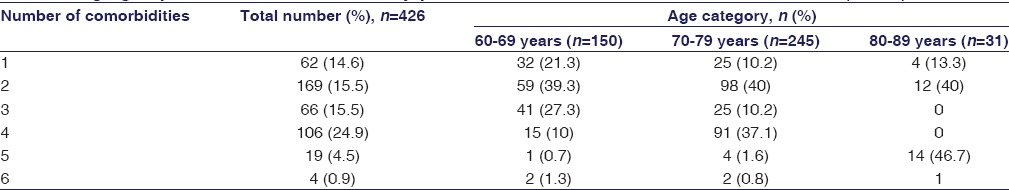

Patients had various comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension (HTN), ischemic heart disease (IHD), chronic kidney disease, central nervous system diseases, dyslipidemia, liver, or joint diseases. There was a positive correlation between increasing comorbidity and polypharmacy (r = 0.559). There was an association between polypharmacy and all individual comorbidities except for liver disease and IHD/coronary heart disease, and it was statistically significant. The proportion of these comorbidities among the patients and the proportion based on age category have been mentioned in Tables 3 and 4.

Table 3.

Distribution of comorbidities among different age groups in geriatric patients and association between comorbidities and polypharmacy

Table 4.

Age group-wise distribution of elderly patients based on the number of comorbidities (n=426)

There was a positive correlation between the number of drugs prescribed and increasing number of comorbidities.

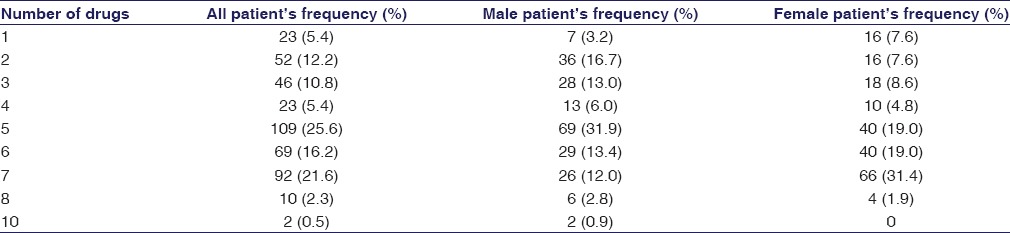

The number of drugs received by the patients was differing among patients. Table 5 depicts the distribution of patients based on the number of drugs they received.

Table 5.

Distribution of number of drugs prescribed among male and female geriatric patients in the study

Out of 426 prescriptions analyzed, 282 prescriptions had five or more than five medications, i.e., polypharmacy was present in 282 prescriptions (66.2%). Around 65.7% of males and 66.7% of females were receiving five or more than five medications. 45.3% of participants in the age group of 60–69 years, 81.6% of 70–79 years age group, and 46.7% of 80–89 years age group were receiving five or more than five medications. The highest prevalence of polypharmacy was seen in 70–79 years age group compared to the other two groups, and it was statistically significant.

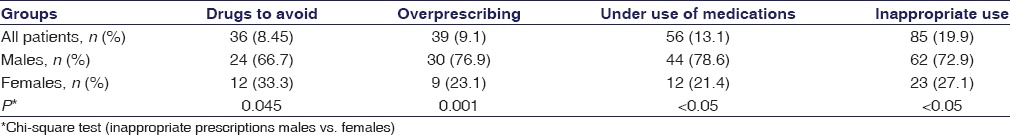

Out of 426 patients, 36 patients (24 males and 12 females) were receiving drugs which were to be avoided as per Beers criteria [Tables 5 and 6]. Thirty-nine patients (thirty males and nine females) were overprescribed as per MAI. Fifty-six patients (44 males and 12 females) were underprescribed as per START criteria.

Table 6.

Proportion of patients receiving inappropriate prescriptions

Eighty-five out of 426 prescriptions (62 males and 23 females) were inappropriate in accordance with Beers criteria, STOPP criteria, START criteria, and MAI. There was a significant difference among males and females in all these parameters [Table 6].

Discussion

Our study aimed at evaluating the proportion of geriatric patients receiving polypharmacy in a tertiary care hospital. In our study, polypharmacy was defined as receiving five or more medications. Our study included patients aged above 60 years.[4] Mean age of the patient was 71.6 ± 6.4 years. Mean number of medications was 4.84 ± 1.95. Our study showed 66.2% of the geriatric patients were receiving five or more medications, i.e., two-thirds of the geriatric patients were labeled as taking five or more medications. In a study done by Slabaugh et al., the prevalence of polypharmacy was 39.4%, and proportion of polypharmacy was higher in the male gender and older individuals.[11] The lower prevalence in the study done by Slabaugh in Italy could be due to larger sample size (8, 87, and 165). There was no difference in the proportion of male and female geriatric patients, and there was also no difference in the proportion of polypharmacy among both the genders in our study. Furthermore, the proportion of polypharmacy was higher in 70–79 years age group (81.6%) in our study similar to the one reported by Dutta and Prashad in his study.[12]

One of the important reasons for polypharmacy in geriatrics is because of the association of multiple comorbidities in them. HTN (75.4%) and DM (51.6%) were seen in majority of geriatric population, being similar to the one seen in a study done by Al Ameri et al. The increased proportion of polypharmacy in 70–79 years could be due to increased number of comorbidity seen in them.[13]

The assessed appropriateness of medications based on Beers criteria, STOPP criteria, START criteria, and MAI. These criteria are widely used by researchers, regulators, and policy-makers. These criteria use an evidence-based approach to regularly update, thus making the criteria more relevant. All these criteria alert the physician and help in reducing the chance of prescribing inappropriate drugs.

Around 36 patients (8.45%) were receiving inappropriate drugs to be avoided based on Beers criteria. Kumar et al., in his study, reported inappropriate prescribing as per Beers criteria in rural areas in Karnataka as 45.41% and also reported analgesics, antidepressants, and vasodilators were the commonly prescribed potentially inappropriate medications.[14] Chung et al.,[15] in his study, reported inappropriate prescribing in hospitalized patients using Beers criteria as 27.8%.[15] The inappropriate drugs prescribed in the present study population, according to Beer's criteria, were chlorpheniramine, promethazine, dicyclomine, digoxin, amitriptyline, and alprazolam.

Prescribing of inappropriate medications in the elderly is low in our study probably because of good knowledge, attitude, and practice among the treating physicians. Overprescribing was assessed using MAI, and 39 patients (9.1%) were receiving overprescribed medications. Under use of medications was assessed as per START criteria, and 56 (13.1%) were underprescribed in our study. The potential prescribing omissions were lesser when compared to study conducted by Lee et al.[16] (26.5%) and Ryan et al.[17] (22.7%). Patients with potential prescribing omissions were receiving a lesser number of medications when compared to other patients. Drugs belonging to the cardiovascular system (antiplatelets and antihypertensives) were the most common omissions. Lee et al.[16] and Ryan et al.[17] also reported cardiovascular drugs (aspirin and statins) as the most common prescribing omissions. Most of the time, geriatric patients receive more medications than needed, and this gets the attention of researchers at the earliest, but a few of the prescribing omissions like that of cardiovascular drugs which significantly decrease morbidity and mortality can be pivotal and go unnoticed. This issue has to be addressed at the earliest, and the treating physician has to address, prioritize, and balance the use of medications in the elderly so that potential prescribing omissions and inappropriate prescribing can be avoided.

Our study aimed at seeing the proportion of inappropriate prescribing in the elderly, and we found that 85 patients (19.9%) were receiving inappropriate medications. Inappropriate prescribing was seen more in the males compared to female, and it was statistically significant too. Harugeri et al. reported the prevalence of inappropriate prescribing as 23.5%.[18] Lai et al. reported that 62.5% of the geriatric patients were receiving inappropriate medications and also reported the increased chance of receiving inappropriate medications was with female gender.[19] The differences in patient characteristics, prescribing pattern, and assessment may be responsible for the variation seen in the prevalence of inappropriate prescriptions in various studies.[20] A geographical variation among physicians' awareness of regarding the existence of a list of inappropriate drugs for the elderly may have also led to these differences.

Strengths of the Study

The study was conducted among geriatric patients attending the OPD in a tertiary care hospital which caters to large number of patients. Apart from Beers criteria, we also used STOPP, START, and MAI to assess the appropriateness of the prescribed medications.

Limitations of the Study

Extrapolation of the findings to general population may be inappropriate as the study was based on the data from the tertiary care hospital. Because of the limited duration of the study with cross-sectional design, impact of inappropriate prescription on patients could not assess. All the criteria used in this study were developed in the Western countries, and the medications listed in these criteria may not have the same adverse effects in different populations of diverse ethnicity. Physicians were not approached to find out their reasons for overprescribing and underprescribing due to time constraints. The assessment of overprescribing was based on a few questions from the MAI which have not been validated independently. However, these questions found to have excellent intra- and inter-rater reliability as noted in the previous reports.[21]

The clinical and financial benefits from stringent application of STOPP and START criteria in geriatrics are still not known. In future, large prospective randomized controlled trials are needed to find out if the stringent application of STOPP and START criteria has appreciable benefits in terms of reduction of ADEs (e.g., falls), cost, hospitalization, and mortality. Being a cross-sectional study, the effectiveness of the medications could not be assessed.

Conclusion

Around 66.19% patients receive polypharmacy. The highest prevalence of polypharmacy is observed in the age group of 70–79 years. A significant number of patients receive drugs which are to be avoided as per Beer's criteria, overprescribed as per MAI, and underprescribed as per START criteria. Inappropriate prescription is observed in the geriatric patients.

Financial Support and Sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Tully MP, Cantrill JA. The validity of explicit indicators of prescribing appropriateness. Int J Qual Health Care. 2006;18:87–94. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzi084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barry PJ, Gallagher P, Ryan C, O'mahony D. START (screening tool to alert doctors to the right treatment) – An evidence-based screening tool to detect prescribing omissions in elderly patients. Age Ageing. 2007;36:632–8. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afm118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bushardt RL, Massey EB, Simpson TW, Ariail JC, Simpson KN. Polypharmacy: Misleading, but manageable. Clin Interv Aging. 2008;3:383–9. doi: 10.2147/cia.s2468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ingle GK, Nath A. Geriatric health in India: Concerns and solutions. Indian J Community Med. 2008;33:214–8. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.43225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sergi G, De Rui M, Sarti S, Manzato E. Polypharmacy in the elderly: Can comprehensive geriatric assessment reduce inappropriate medication use? Drugs Aging. 2011;28:509–18. doi: 10.2165/11592010-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maher RL, Hanlon J, Hajjar ER. Clinical consequences of polypharmacy in elderly. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2014;13:57–65. doi: 10.1517/14740338.2013.827660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.By the American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2015 updated Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:2227–46. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O'Mahony D, O'Sullivan D, Byrne S, O'Connor MN, Ryan C, Gallagher P. STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: Version 2. Age Ageing. 2015;44:213–8. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afu145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanlon JT, Schmader KE, Samsa GP, Weinberger M, Uttech KM, Lewis IK, et al. A method for assessing drug therapy appropriateness. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:1045–51. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90144-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.John NN, Kumar AN. A study on polypharmacy in senior Indian population. Int J Pharm Chem Biol Sci. 2013;3:168–71. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Slabaugh SL, Maio V, Templin M, Abouzaid S. Prevalence and risk of polypharmacy among the elderly in an outpatient setting: A retrospective cohort study in the Emilia-Romagna region, Italy. Drugs Aging. 2010;27:1019–28. doi: 10.2165/11584990-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dutta M, Prashad L. Prevalence and risk factors of polypharmacy among elderly in India: Evidence from SAGE Data. Int J Public Ment Health Neurosci. 2015;2:2394–4668. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al Ameri MN, Makramalla E, Albur U, Kumar A, Rao P. Prevalence of polypharmacy in the elderly: Implications of age, gender, comorbidities and drug interactions. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2014;1:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumar KL, Holyachi S, Reddy K, Nayak NB. Prevalence of polypharmacy and potentially inappropriate medication use among elderly people in the rural field practice area of a medical college in Karnataka. Int J Med Sci Public Health. 2015;4:10771–5. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chung H, Suh Y, Chon S, Lee E, Lee BK, Kim K. Analysis of inappropriate medication use in hospitalized geriatric patients. J Korean Soc Health Syst Pharm. 2007;24:115–23. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee SJ, Cho SW, Lee YJ, Choi JH, Ga H, Kim YH, et al. Survey of potentially inappropriate prescription using STOPP/START criteria in Inha University Hospital. Korean J Fam Med. 2013;34:319–26. doi: 10.4082/kjfm.2013.34.5.319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ryan C, O'Mahony D, Kennedy J, Weedle P, Byrne S. Potentially inappropriate prescribing in an Irish elderly population in primary care. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;68:936–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2009.03531.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harugeri A, Joseph J, Parthasarathi G, Ramesh M, Guido S. Potentially inappropriate medication use in elderly patients: A study of prevalence and predictors in two teaching hospitals. J Postgrad Med. 2010;56:186–91. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.68642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lai HY, Hwang SJ, Chen YC, Chen TJ, Lin MH, Chen LK. Prevalence of the prescribing of potentially inappropriate medications at ambulatory care visits by elderly patients covered by the Taiwanese National Health Insurance program. Clin Ther. 2009;31:1859–70. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2009.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pradhan S, Panda A, Mohanty M, Behera JP, Ramani YR, Pradhan PK. A study of the prevalence of potentially inappropriate medication in elderly in a tertiary care teaching hospital in the state of Odisha. Int J Med Public Health. 2015;5:344–8. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanlon JT, Schmader KE, Samsa GP, Weinberger M, Uttech KM, Lewis IK, et al. A method for assessing drug therapy appropriateness. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:1045–51. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90144-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]