Abstract

Background

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) disproportionately impacts Latino youth yet few diabetes prevention programs address this important source of health disparities.

Objectives

To address this knowledge gap, we describe the rationale, design, and methodology underpinning a culturally-grounded T2D prevention program for obese Latino youth. The study aims to: 1) to test the efficacy of the intervention for reducing T2D risk, 2) explore potential mediators and moderators of changes in health behaviors and health outcomes and, 3) examine the incremental cost-effectiveness for reducing T2D risk. Latino adolescents (N=160, age 14–16) will be randomized to either a 3-month intensive lifestyle intervention or a control condition. The intervention consists of weekly health education delivered by bilingual/bicultural promotores and 3 moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (PA) sessions/week. Control youth receive health information and results from their laboratory testing. Insulin sensitivity, glucose tolerance, and weight-specific quality of life are assessed at baseline, 3-months, 6-months, and 12-months. We will explore whether enhanced self-efficacy and/or social support mediate improvements in nutrition/PA behaviors and T2D outcomes. We will also explore whether effects are moderated by sex and/or acculturation. Cost-effectiveness from the health system perspective will be estimated by the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio using changes in insulin sensitivity at 12-months.

Conclusions

The results of this study will provide much needed information on how T2D prevention interventions for obese Latino youth are developed, implemented and evaluated. This innovative approach is an essential step in the development of scalable, cost-effective, solution oriented programs to prevent T2D in this and other high-risk populations.

Keywords: Diabetes Prevention, Latino, Health Disparities, Health Promotion, Obesity

INTRODUCTION

Obesity and type 2 diabetes (T2D) represent some of the most significant public health challenges facing our society. Disparities in obesity and T2D emerge early in life and disproportionately impact Latino populations. Latino youth exhibit higher rates of insulin resistance [1] and pre-diabetes [2] than white youth and nearly 30% of obese Latino youth exhibit pre-diabetes.[3] These data support estimates by the CDC that up to 50% of all Latino youth born in the year 2000 will develop T2D in their lifetime.[4] In addition to adverse physical health, recent data suggest that obese Latino youth are more likely to experience psychosocial consequences including symptoms of depression and anxiety [5] as well as reduced perceived quality of life (QoL). The extent and magnitude of adverse negative health consequences among obese Latino youth set the stage for long-term morbidity and mortality. Therefore, interventions aimed at improving physical and psychosocial health outcomes among Latino youth are urgently needed.

Obesity interventions for youth traditionally target individual level behavior changes including diet and exercise to support weight loss.[6] These general approaches to encourage healthy behaviors among heterogeneous populations (overweight/obese, children/adolescents, and minority/non-minority) often fail to address contextual factors that influence health behaviors among population sub-groups. As such, most programs to date have shown limited efficacy for reducing obesity among youth.[7] Interventions that do incorporate a multilevel perspective rarely include health outcomes beyond weight-loss, do not consider sociocultural or developmental perspectives in their designs, and almost never explore the mechanisms through which the intervention is mediated.[8] The complexity of obesity-related health disparities necessitates that evidence-based programs include culturally and biologically homogeneous populations, incorporate robust outcome measures, and test the mechanisms of efficacious outcomes using rigorous randomized controlled designs. Such comprehensive studies will provide the framework for solution-oriented programs and policies that will ultimately close the obesity-related health disparities gap among minority youth.

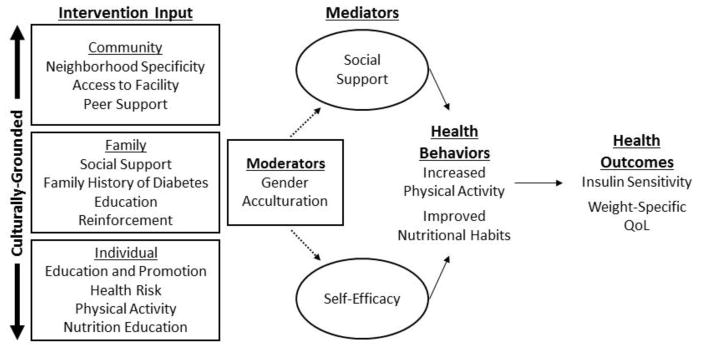

The Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) has established that T2D can be prevented or delayed in high-risk adult populations.[9] The original DPP curriculum has been successfully adapted and incorporated into the local community setting with community input into its development, design and implementation.[10] The DPP was not designed nor has it been tested in high–risk youth, a population where academic-community partnerships may be ideal. These types of partnerships represent an opportunity for translating obesity and diabetes research findings into “real-world” settings and have proven successful for preventing obesity in young children.[11] However, to date, the availability of community-based diabetes prevention programs focusing on obese Latino adolescents is extremely limited in the scientific literature.[12] Given that adolescence represents a critical period for the onset of adverse obesity-related conditions,[13] intervening during this developmental period is a strategic and indicated opportunity for preventing T2D. In order to extend the field, we have developed a 5-year study to test the short-term and long-term efficacy of Every Little Step Counts (ELSC), a culturally-grounded diabetes prevention intervention for obese Latino adolescents (Specific Aim 1). In addition to testing the efficacy, we will explore potential mediators (Specific Aim 2) and moderators (Specific Aim 3) of health behavior changes and health outcomes (Figure 1). Lastly, we will estimate the initial cost-effectiveness of the intervention for increasing insulin sensitivity (Specific Aim 4). This paper describes the design, methodology, and rationale for the randomized-controlled study.

Figure 1.

METHODS

Study Design

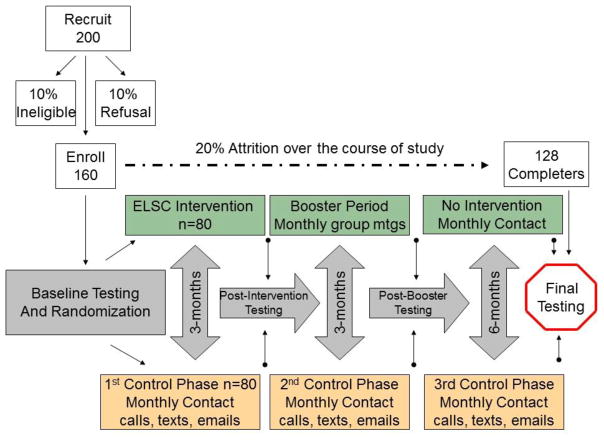

We propose a randomized controlled trial of 160 obese Latino adolescents aged 14–16 to test the short-term (3-month) and long-term (9-month) efficacy of a culturally-grounded, community-based Every Little Step Counts (ELSC) lifestyle education intervention to improve insulin sensitivity and weight-specific QoL. Youth will be randomized to either 3-months of intensive ELSC lifestyle intervention consisting of weekly group education sessions (~1-hr each) and 3 moderate to vigorous group PA sessions per week (~1-hour each) or a control group that will receive health information material and monthly phone calls, emails, or texts throughout the 3-month period. The intervention group will complete three monthly booster sessions following the intensive intervention period. All participants will undergo testing at baseline, 3-months (post-intervention), 6-months (post-booster), and 12-months (9-months post-intervention) and control youth will be offered a modified version of the intervention upon completion. This design (Figure 2) not only allows us to examine the short and long-term efficacy of the intervention but having multiple points of contact with participants facilitates retention efforts. We will oversample with the conservative assumption that 20% of youth approached will be ineligible or not interested and 20% will be lost to attrition over the course of the study, thus leaving a proposed final sample size of 128 participants for analysis at 12-months. Given the rapid onset of T2D in youth with prediabetes and the ethical implications of randomizing a participant with prediabetes to a control group for a year, any participant who meets the American Diabetes Association criteria of prediabetes at baseline (either a fasting glucose ≥ 100mg/dl and/or a 2-hour post-challenge glucose ≥ 140mg/dl) will automatically be assigned to the intervention group.

Figure 2.

Study Design

Ethics

The study protocol and all study-related documents will be approved and monitored by the Institutional Review Board at Arizona State University. The study is registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (Clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT01236794). Written parental consent and child assent will be obtained by study staff prior to any data collection procedures.

Participants

Equal number of males and females will be recruited and must meet specific inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria include: Latino ancestry; self-report age 14–16 at time of enrollment; and obesity defined as BMI percentile ≥ 95th percentile for age and gender or BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2. Youth will be excluded if they are taking medication(s) or diagnosed with a condition that could influence carbohydrate metabolism, physical activity, and/or cognition, have type 2 diabetes as defined by a fasting plasma glucose ≥ 126 mg/dl or 2-hour plasma glucose ≥ 200 mg/dl, have been recently hospitalized (previous 2 months), are currently enrolled in (or within previous 6 months) a formal weight loss program, or are diagnosed with depression or other mental health condition that may adversely affect quality of life.

Recruitment Strategies

Recruitment for clinical studies involving pediatric participants may be difficult, particularly in vulnerable populations. The primary means of recruitment will be through our clinical partner, the St. Vincent de Paul Medical and Dental Clinic which is an established and trusted entity in the local Latino community. The rationale for recruiting through the clinic is based upon the nature of this project testing the efficacy of a community-based intervention using “real-world” strategies for reaching vulnerable and underserved youth. Their referral network pulls from over 100 schools, community centers, churches, Latino serving agencies, and healthcare organizations in the greater Phoenix area. We will collaborate with this network and focus recruitment efforts in the area surrounding the intervention delivery site of the Downtown Phoenix YMCA. This site has direct access to public transportation and is in close proximity to several junior and senior high schools within the clinic’s referral network. Successful recruitment efforts will be facilitated through distribution of flyers and advertisements in Spanish language media, hosting presentations, and direct contact/referral. Recruitment efforts will be further strengthened by employing bilingual/bicultural research staff to assist with recruiting, consenting, enrollment and data collection, including pediatric and specially trained research nursing staff in our clinical unit. In anticipation of potential barriers to participation, assistance with transportation to and from research and intervention facilities will be provided via bus and light rail passes if needed. Youth are compensated $50 for their time and effort for participating in each testing visit. Further, families will receive results of the metabolic testing and the opportunity to participate in an intervention with a high likelihood of directly benefitting the individuals enrolled.

Detailed Methodology

Informed consent

Written consent and assent will be administered by bilingual/bicultural study staff to parents/guardians and adolescents. Participants are informed they are free to withdraw from the study at any time, that nonparticipation will not affect any services, and that their names will not appear on study materials. We will use a unique 4-digit number to code data for confidentiality. All study-related materials are available in English and Spanish and bilingual/bicultural research staff are available to administer consent/assent, collect data, and answer questions.

Health Screenings

Participants arrive at the ASU Clinical Research Unit at ~8:00 AM after an overnight fast. A medical and family history including in utero exposure to gestational diabetes will be taken and height, weight, and waist circumference measured to the nearest 0.1cm, 0.1 kg, 0.1cm, respectively. Temperature is taken to rule out acute illness. Youth with signs or symptoms acute illness are rescheduled. Sitting blood pressure is measured in triplicate using an appropriately-sized cuff on the right arm after the subject has rested quietly for 5 min.[14] A fasting lipid panel is collected to measure cholesterol (Total, HDL, and LDL) and triglycerides. These assessments follow current recommendations for screening in obese youth[15] and are used in the curriculum to discuss the health risks of obesity. In addition, participants complete an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) where blood samples are collected under fasting conditions and every 30 minutes after ingestion of 75-grams of glucose in solution (explained in detail under primary outcomes section below). This test is considered the gold-standard assessment for T2D as it provides both fasting and post-challenge glucose measures that are used to diagnose T2D. Any youth who meets the American Diabetes Association criteria for type 2 diabetes during the study (fasting ≥ 126 mg/dl or 2-hour post-challenge glucose ≥ 200 mg/dl) will be referred for follow-up treatment. Our experience in this community suggests the results of metabolic testing are an important and meaningful benefit to families.

ELSC Lifestyle Curriculum

The ELSC intervention was developed through the team’s extensive experience working with obese Latino youth and our review of the literature. Components of the intervention are based upon enhancing key constructs of Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) which, is widely used in individual and public health approaches to health promotion and disease prevention and emphasizes that individual, social and environmental factors interact in a reciprocal manner to influence behavior.[16] SCT constructs such as increasing self-efficacy, observational learning, goal setting, self-monitoring, and fostering social support are integrated into each intervention session. Bilingual/bicultural promotores deliver weekly education classes in groups to adolescents and their families that focus on family history and obesity-related health risks, healthy eating, family roles and responsibilities, physical activity and inactivity, and emotional well-being. Adolescents and parents are asked to complete a behavior contract at the beginning of the program and readiness to change is documented and discussed. Participants are presented with their baseline clinical metabolic measures and this information is used to initiate the discussion on making healthy lifestyle choices. Classes are delivered using an interactive format where youth and families are encouraged to share their personal experiences, beliefs, successes, and challenges. Participants learn behavior change strategies such as goal-setting, self-monitoring, decision-making, and positive self-imaging as they pertain to the 12 lifestyle classes outlined in Table 1. Out of class activities such as grocery shopping with parents to prepare a healthy family meal are used to facilitate curriculum integration into day-to-day lifestyle changes. Throughout the program, youth and their families are asked reflection questions about how they incorporate information learned into their everyday life (e.g. What did you do last week to improve how you feel about yourself?). Success is recognized and acknowledged and challenges are discussed with a focus on strategies to overcome barriers. At the conclusion of the program, youth are presented with a certificate of completion and are applauded for their efforts by the Promotores, families, peers, and research team.

Table 1.

| Class 1. | Introduction |

| Class 2. | Understanding your health status |

| Class 3. | Healthy meal planning |

| Class 4. | Reducing sugar and fat intake |

| Class 5. | Increasing fiber intake |

| Class 6. | Eating breakfast |

| Class 7 | Appropriate portion sizes |

| Class 8. | Healthy snacking |

| Class 9. | Importance of Physical Activity |

| Class 10. | Enhancing self-efficacy |

| Class 11. | Enhancing Self-esteem |

| Class 12. | Sustaining a healthy and balanced lifestyle |

Physical Activity

The PA component includes structured and unstructured exercise 3 days/week for approximately 1-hour. The structured component includes aerobic and resistance exercises that are progressive in nature with the first 2–4 weeks focusing on motor skill acquisition, exercise confidence, and developing a fitness base. Aerobic exercises include various group activity classes (e.g. spinning and cardio kick-boxing) delivered by YMCA instructors with the goal of maintaining heart rates > 150 BPM. Heart rate monitoring and rate of perceived exertion are used to monitor and document exercise intensity throughout the program. Resistance exercise includes circuit training using age and size appropriate equipment. Resistance training is incorporated because previous studies suggest this form of exercise is enjoyable and metabolically beneficial for obese youth.[17] Unstructured exercises include team sports, games, and activities that promote social support, encouragement, and bonding among youth. In our previous studies, we have observed significant heterogeneity in baseline fitness, activity levels, and exercise experience so youth are encouraged to work at their own pace and support their peers at all levels. Healthy competition is encouraged but any negativity or teasing is immediately addressed on an individual and group level. Adolescents are encouraged to utilize the YMCA outside of the intervention and the YMCA makes special membership arrangements for families participating in the project.

Booster Sessions

Three booster sessions are held on a monthly basis following the completion of the intensive ELSC lifestyle intervention period. These sessions are designed to support ongoing healthy lifestyle behaviors and address any challenges encountered in maintaining a healthy lifestyle. Post-intervention clinical measures are returned to participants and changes are discussed in the context of maintaining healthy lifestyle behaviors.

Control Program

Control participants and families are provided with the results of their clinical measures and given information on health risks and healthy lifestyle behaviors. The research team contacts control adolescents via phone, text, or email (adolescent/parent preference) on a monthly basis throughout the 12 month study. Upon completion of the study, control youth are offered an abridged version of the intervention and a 1-year membership to the YMCA. Although it would be preferable to offer the entire intervention to control youth, this is not feasible due to study costs and time constraints.

Intervention Fidelity

Challenges exist when trying to translate scientifically sound interventions into real-world practice settings so the best science can be used to address the practical concerns of local communities. We have identified several critical factors for resolving tensions between fidelity and fit when delivering prevention interventions in the community.[18] These factors informed the development of the ELSC lifestyle intervention and include specificity of curriculum to the target audience (e.g., age, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, health status, and family structure), program development (community input, buy-in, and integration), and program delivery (e.g., type of staff, cultural competence of staff, location of delivery). The intervention was developed in collaboration with the community, for the community, to be delivered by health educators in the community. Nonetheless, strong science necessitates that rigorous methods be employed in order to ensure fidelity of intervention delivery.[19] Therefore, we employ the following strategies: comprehensive training of study staff and health educators by the research team, a detailed curriculum manual for intervention delivery, weekly documentation of physical activity dosage (exercise intensity by heart rate and duration), participant attendance sheets, collection and review of participant workbooks used for in-class and out of class activities to ascertain processing of material, and direct observation of 25% of the ELSC lifestyle classes by a study team member using the curriculum manual to ensure fidelity of health education delivery. In addition to these fidelity checks, potential variation in intervention dosage (e.g., attendance) is accounted for using statistical procedures. Because attendance to sessions is critical, we use frequent reminder phone calls and texts and will assist with transportation if needed. Participants and families that exhibit attendance barriers (<75% attendance through week 6) individually consulted to identify challenges with the goal of implementing corrective strategies.

Follow-Up

During the 6-month post-intervention period, all youth are contacted on a monthly basis via phone, text, or email. Participants are scheduled for their final data collection visit (12-months after baseline) and all data collection procedures are repeated.

Primary Outcomes

Insulin Sensitivity

Insulin sensitivity is assessed via the multiple sample OGTT. Blood samples are collected at times −15, −5, 30, 60, 90 and 120 min (before and after the administration of glucose solution) for measurement of plasma glucose (glucose oxidase, YSI INC., Yellow Sprigs, OH) and insulin (ELISA, ALPCO Diagnostics, Windham, NH). At time 0, participants ingest 1.75g/kg body weight (up to 75g) of glucose solution. Insulin Sensitivity is estimated by the whole-body insulin sensitivity index (WBISI) using plasma glucose and insulin values determined during the OGTT.[20]

The WBISI derived from an OGTT is calculated using the following formula, and is proposed to capture insulin action at both hepatic and skeletal muscle tissues into an integrated composite measure.[20] Correlation estimates between the WBISI and the gold-standard hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp in obese youth have been shown to be high (r = 0.78, p < 0.0005).[21] Compared to the clamp, an OGTT is considered a less risky procedure and may be better tolerated in the pediatric population. We recently reported that the WBISI derived from an OGTT is more sensitive than fasting measures for assessing changes in insulin sensitivity among obese Latino adolescents participating in lifestyle interventions.[23] In addition to better capturing changes in insulin sensitivity over time, the OGTT is preferred over fasting measures for differentiating T2D risk in youth and thus, offers a direct benefit to participants who may be at high risk for T2D.[22]

Perceived Quality of Life

Weight-specific QoL is assessed using the multicultural Weight and Quality of Life Instrument. The instrument measures three domains related to QoL (Self, Social, and Environmental) and was developed using ethnographic methods drawing directly on experiences of and language used by overweight white, African American, and Mexican American youth.[24] The instrument was developed to be used for evaluating weight-related interventions in clinical and community research and shows good reliability (ICC ≥ 0.7) and congruence with other measures of QoL for assessing weight-specific QoL in children and adolescents. It has been shown to be more sensitive then generic measures for detecting QoL changes in obese youth participating in lifestyle interventions.[25]

Assessment of Lifestyle Behaviors

Physical Activity

PA will be measured using the 3-Day PA Recall (3DPAR), an interviewer-administered recall instrument that measures the type of PA performed during the past 3 days (e.g. Tues, Mon, Sun). The 3DPAR captures up to 55 activity types performed every 30 minutes between 7:00 a.m. and midnight, presented as morning, afternoon, and evening to aid recall. Participants recall the primary type of activity (e.g., sleep/bathing, eating, after-school/spare time/hobbies) they perform during each 30-minute block and rate each activity as light, moderate, hard, or very hard intensity. Pictures of activities are provided to help respondents assess the intensity of each activity listed.[26] The 3DPAR allows for assessment of time spent in sedentary behaviors and types of activity that can be useful to identify differences in PA patterns between adolescents.[27] Activities selected for each 30 minute period are assigned a MET level (MVPA ≥ 3.0 METs; VPA ≥ 6.0 METs) with summary scores tallied as total METs/day.

Nutrition Assessment

Dietary intake will be measured using the 2007 Block Food Screener for Ages 2–17. This 41-item screener assesses foods eaten during the previous week and was designed to identify dietary intake by food group. The focus of this screener is the intake of fruit and fruit juices, vegetables, potatoes (including French fries), whole grains, meat/poultry/fish, dairy, legumes, saturated fat, and “added sugars” (in sweetened cereals, soft drinks, and sweets). This screener was developed and adapted from the Block Kids 2004 Food Frequency Questionnaire and designed for self-administration by adolescents. National dietary surveys were used to inform the food selections to query and to identify appropriate portion sizes and nutrient composition to apply. The screener includes items commonly consumed by Latino youth (e.g., “licuados” or fruit smoothie).

Hypothesized Mediators Proximal to the Intervention

Social Support

A core value among the Latino culture is familism; the notion that family is a central and important construct in terms of identity, involvement, and influence.[29] Similarly important is the concept of collectivism which reflects the social patterns and behaviors of individuals in the context of being tightly linked to other members (related and un-related) within the Latino community. These cultural values are operationally stronger among Latino youth than other racial/ethnic groups in regards to influencing individual behaviors.[30] For this reason, social support from both family and friends is thought to be a major influence on leisure time physical activity among Latinos.[31] Compared to other girls, Latina girls receive less support for physical activity.[32] Within Latino children however, social support from friends and family is significantly and positively correlated with physical activity.[33] Given that social support for physical activity is a primary predictor of activity levels over time in youth[34] and social support is an important predictor of health-related QoL in obese youth[35], we believe this construct may be a critical theoretical mechanism underlying improvements in health behaviors and outcomes. Social support will be assessed using the PACE + Physical Activity and Diet Survey for Adolescents.[36] This instrument measures social support for physical activity and health eating (decrease consumption of low-fat foods, and increase consumption of fruits and vegetables).

Self-Efficacy

Self-efficacy is proposed by Bandura to be the most important prerequisite for behavior change.[37] As such, self-efficacy is a commonly assessed mediator in interventions targeting obesity-related behaviors with support for this construct as an important mechanism underlying dietary and PA behavior change among youth.[38, 39] Moreover, self-efficacy predicts long-term weight-loss among children participating in an obesity intervention.[40] Therefore, enhanced self-efficacy may be an important mediator of long-term success for maintaining health behaviors and improved health outcomes in obese youth. Self-efficacy will be assessed using the PACE + Physical Activity and Diet Survey for Adolescents which assesses confidence for physical activity and healthy eating despite potential barriers.

Hypothesized Moderators of Intervention Effects

Biological Sex

Obesity rates among Latino youth are higher in boys compared to girls[41] but T2D is more prevalent in girls.[42] Cross-sectional analyses from NHANES have identified important sex interactions in the associations between health behaviors (nutrition and PA) and obesity-related health outcomes in youth and interactions differ by racial/ethnic subgroupings.[43] Whether biological sex moderates how obese Latino youth respond to lifestyle intervention in terms of health behaviors and health outcomes remains largely unknown. Therefore, we will explore whether sex serves to moderate ELSC intervention effects.

Acculturation

Given the complex, multidimensional processes underlying cultural adaptation, we will employ several tools to assess acculturation. Linear measures will include primary language spoken in the home and with friends, country of origin, and parents/grandparents country of origin. Comprehensive multidimensional measures of acculturation will include the brief Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans-II (ARSMA-II) for youth.[44] The brief ARSMA-II is a 12-item scale containing questions related to Anglo/White and Latino/Hispanic preferences. The measure can assess acculturation in terms of the individual’s identification with each of two distinct cultures: the American culture and the Latino culture. The ARSMA-II has been shown to be a valid and reliable instrument to assess acculturation among Latino youth.[44] In addition to the ARSMA-II, we will use the Acculturation, Habits, and Interests Multicultural Scale for Adolescents (AHIMSA) developed by Unger et al.[45] The AHIMSA is an 8-item scale developed specifically to assess acculturation in adolescents through multiple cultural preference domains. Previous work employing both the AHIMSA and ARSMA-II in a sample of Latino youth found only modest correlations between the 2 scales (r = 0.15–0.40) which suggests that each scale may tap a different aspect of acculturation.[46] This is not surprising, given the complex process of acculturation especially during adolescence. Nonetheless, it underscores the need for multiple measures of acculturation to explore if this important construct can help explain in whom the intervention works best.

Additional Measures

Body Composition

Total body composition will be determined using bioelectrical impedance analysis (TBF-300A, Tanita Corp of America, Arlington Heights, Illinois). This measure partitions the body into 2 compartments (fat mass and fat-free) and provides estimates of total fat mass, percent fat, and fat-free mass. Body composition will be controlled for due to the known sex dependent changes in body composition and insulin resistance during growth[47].

Socioeconomic Status (SES)

SES will be determined by questionnaire of the parents (education level and household income) as SES has been shown to be associated with insulin resistance in youth.[48]

Pubertal Maturation

Pubertal status will be assessed by self-report using the Pubertal Development Scale which has a high correlation between children’s self-rating scores and pediatrician assessment of Tanner stage based on pubertal growth (r=0.87–0.84, p< 0.001).[49] Although we expect most youth to be post-pubertal, any changes in pubertal status will be controlled for as they may influence insulin sensitivity.

Statistical Models and Methods of Analysis

Specific Aim 1 will test the hypothesis that participants who take part in the ELSC intervention will exhibit significantly greater increases in insulin sensitivity and weight-specific QoL compared to controls. ANCOVA models will use pretest measures of the outcome variable as a covariate and the experimental groups (i.e., intervention vs. control) as the groups being compared. This analysis represents the adjusted “main effect” of intervention group membership. Effect size measures will be calculated, along with tests of significance. Analyses will be repeated for each outcome.

We will also consider multiple waves of outcome data within a linear mixed model or multilevel approach. The three repeated post-test and follow-up waves will be modeled as a linear function of time, with intercepts and slopes that vary randomly across participants. These “within-person” intercepts and slopes are, in turn, modeled initially as a linear function of two “between-person” predictors: (1) the outcome pretest score, and (2) intervention group membership (intervention vs. control).

Specific Aim 2 will explore the hypothesis that effects of the ESLC intervention on insulin sensitivity and weight-specific QoL are mediated by proximal (self-efficacy and social support) and distal (physical activity and nutrition) mediator variables. The initial models will consider proximal and distal mediators separately. Each mediation model will include three variables: (1) group membership represented by dummy codes, (2) a proximal mediator measure (e.g., self-efficacy), and (3) an outcome measure (e.g., QoL). The model specifies direct paths from group membership to the mediator and outcome. Path coefficients and standard errors for these paths will be estimated. Effect size measures will include: (1) direct effects on outcome measures, and (2) mediated or indirect effects on outcome measures. The latter can be estimated using path coefficient estimates with standard error estimated using separate calculations.[50] For proximal mediator models, the mediators will be measured at the immediate post-test wave or the 3-month follow-up wave and the outcome measures will either be chosen from the 3-month or 9-month follow-up waves. For distal mediator models, the mediators will be measured at the 3-month follow-up and the outcome measures will be taken from the 9-month follow-up wave. Separate models will be constructed for different mediator/outcome pairings. Finally, exploratory path models that include both proximal and distal mediators will be evaluated. Each of these models will include four variables: (1) intervention group membership, (2) proximal mediator measure from the immediate posttest wave, (3) distal mediator measure from 3-month follow-up wave, and (4) outcome measure from 12-month follow-up wave.

Specific Aim 3 will explore potential moderators of the intervention effects on outcomes. We will use ANCOVA models to examine biological sex and acculturation as potential moderators. Sex will be incorporated in the ANCOVA’s planned under Specific Aim 1 creating a 2x2 factorial ANCOVA. Moderator effects will be represented as an interaction between sex and group membership. The nature of the interaction is studied using group means after adjustment for the covariate (pretest) and effect size is estimated using measures such as omega-squared.[51] Acculturation will also be incorporated in the ANCOVA models as a covariate and interactions will be tested for significance. Johnson-Neyman technique will examine the form of interaction and regions in which group differences are significant.[52]

Specific Aim 4 will estimate the initial cost effectiveness of the ELSC intervention compared to standard care based on changes in insulin sensitivity. Initial cost-effectiveness will be estimated using the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) conducted from the health system perspective using insulin sensitivity at 9 months post-intervention, direct medical costs, and direct non-medical costs. Base case and sensitivity analyses will be conducted and carried out using TreeAge Version 11. Direct medical costs include: personnel, intervention materials, lab tests, and procedures. The direct non-medical costs will be participant time for travel and commercial services for PA and nutrition. Case-base analysis model will use 1-year ELSC intervention costs and insulin sensitivity at 9-month post-intervention. ICERs will be calculated by dividing incremental costs by incremental effectiveness (change in insulin sensitivity). Costs will be inflated 3% annually and expressed in 2015 US dollars. Sensitivity analyses will be modeled based on those conducted for the DPP lifestyle intervention.[53] We will assume that the adherence to the ELSC intervention will decrease by 20% after year 1.

DISCUSSION

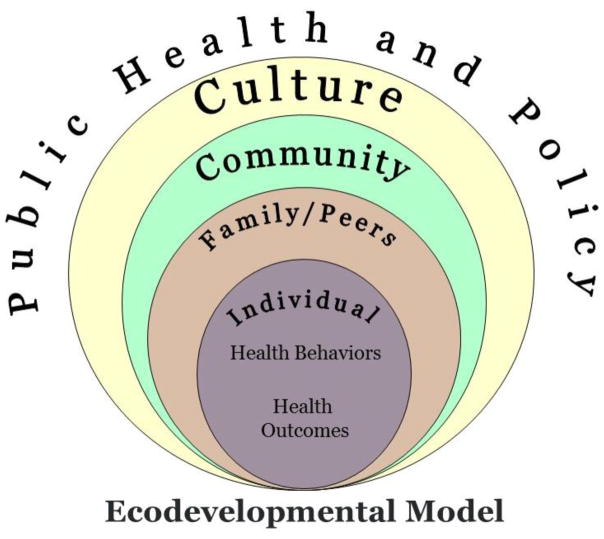

Despite the fact that Latino youth are one of the fastest growing segments of the U.S. population and experience significant diabetes-related health disparities, there is an evidence-gap regarding how to prevent T2D in this vulnerable population. The most successful T2D prevention programs focus on lifestyle changes that include improvements in dietary habits and increases in physical activity that are supported by behavioral change strategies. To date, these programs have almost exclusively been conducted in adult populations. Given that up to 50% of newly diagnosed cases of diabetes in the pediatric population are T2D, there is a pressing need to develop and test programs for preventing diabetes in high-risk youth.[54] In particular, these programs must take into account the complex contextual milieu that contributes to disproportionate rates of T2D among youth from minority and low socioeconomic communities.[55] In this report, we have presented the design and methodology for ELSC, a targeted diabetes prevention program for obese Latino youth. The overall program is framed within an Expanded Ecodevelopmental model (Figure 3) in order to include multiple ecodevelopmental levels that influence individual health behaviors and health outcomes during the critical life period of adolescence. Included in these levels of influence are social (family and friends), community, culture, and policy level factors. Programs that address multiple ecodevelopmental levels are likely to have a more robust and sustained effect than programs that only target individual factors.

Figure 3.

SOCIAL INFLUENCES

For youth, parents serve as the primary role models and are responsible for structuring the home environment, meal preparation, availability of healthy snacks, and supporting physical activity opportunities.[56] For these reasons, family-based weight management interventions are likely to have greater success than those that focus on the child alone. Therefore, in the current intervention, parents will be required to attend the health education sessions in order to enroll in the study, and class activities focus on making lifestyle changes as a family. In addition to parents, other family members will be encouraged to attend health education sessions and siblings who were not eligible for the study can participate in the physical activity sessions. However, as important as family support, adolescents place a high value on social support from peers. As such, fitness classes will be delivered in groups where teams of youth learn and practice new physical activity behaviors and provide verbal encouragement for reaching individual and collective fitness goals. These classes are designed to build self-efficacy for physical activity while fostering social support from family and friends.

COMMUNITY IMPACT

Beyond social influences, the curriculum was developed in partnership with community organizations, to be delivered in the community, by the community, for community members. Partnering with well-established community organizations that are attune to the needs, challenges, and available resources to support health promotion and diabetes prevention efforts further grounds the program within the local community. Given that the current healthcare system in the US is poorly equipped to implement robust health promotion and disease prevention programs, alternative approaches for addressing this challenging problem are needed. If proven to be successful, this intervention can be taken to scale. That is, partnering with community agencies to deliver diabetes prevention for high-risk youth could serve as a model with far reaching implications for this growing public health epidemic that disproportionately impacts low income and minority communities. In particular, the YMCA engages more than 9 million youth and 12 million adults in more than 10,000 neighborhoods across the country.[57] It is estimated that ~60% of the US population lives within 3 miles of a YMCA.[58] Moreover, the YMCA’s policy is to be accessible to all and therefore will not to turn away any individual or family for financial, cultural, religious, or other reasons. As an organization, the YMCA has partnered with the CDC to launch the Healthier Communities Initiative which supports efforts that focus on making policy and environmental changes that support healthy lifestyles in communities across the US.[59] Lastly, the YMCA is involved with one of the most successful, wide-scale translations of the Diabetes Prevention Program for adults.[10] Embedding effective diabetes prevention programs in national organizations such as the YMCA greatly enhances the potential for scalability. Community-based diabetes prevention programs capitalize on the expertise and trust that community organizations possess and are more readily translatable if successful.

GROUNDING IN CULTURE

Integrating culturally-congruent concepts and content into health education interventions has been recognized by the CDC[60] and the Institute of Medicine[61] as a critical leverage point for reaching and engaging minority populations around health promotion and disease prevention. As an example, cultural norms and values surrounding weight, obesity, and preferred body size for youth differ widely across racial and ethnic sub-groups.[62] As such, the influence of norms and values on obesity-related health behaviors (e.g., physical activity and diet) likely differ across racial and ethnic groups. In contrast to weight, improving health is a more universally accepted concept so targeting health improvements over weight-loss per se may be a more viable intervention approach among obese minority youth. In order to acknowledge this perspective, the ELSC intervention targets diabetes risk reduction through improvements in health behaviors (nutrition and physical activity) as opposed to employing a weight-centric approach. Children and families learn about diabetes risk factors in the context of their child’s baseline laboratory values and learn behavior strategies that focus on health promotion as opposed to weight loss. This approach may be more effective for motivating and sustaining behavior change particularly among an adolescent population who are likely to remain obese for the remainder of their life.[63] Additional cultural leverage points include the use of promotores (community health workers) to deliver the education classes. Promotores have been widely used to deliver health promotion and disease prevention programs within Latino communities [64] and engender a sense of cultural connectedness that may facilitate communication of information and ultimately more meaningful uptake of behavior change strategies for Latino families. The promotores in the present study will receive extensive training on the delivery of health promotion and disease prevention. In addition to this comprehensive training, a curriculum manual will be used during the ELSC intervention and fidelity checks will be conducted on a regular basis by research staff to ensure that the intervention is delivered as intended.

POLICY IMPLICATIONS

Projections suggest that by the time today’s youth enter the adult workforce, obesity will account for as much as $956 billion dollars (16–18%) of the total US health-care costs.[65] Couple this with the ~$250 billion dollar current annual cost of T2D in the US,[66] there is a clear economic need for cost-effective T2D prevention programs. While the Affordable Care Act calls for the increase of programs to prevent chronic disease, policy makers are constantly challenged with the task of deciding which programs merit funding amidst finite resources. In order for diabetes prevention programs to be positioned for wide-scale dissemination, the costs in relation to the potential benefits must be known. Therefore, incremental cost effectiveness of the intervention for increasing insulin sensitivity will be calculated. Cost-effective improvements in insulin sensitivity, which, is a prelude to the development of T2D, could be leveraged to support diabetes prevention programs with policy makers and third-party payers.

In addition to integrating multiple levels of influence in the approach, there are several innovative components of the design that have the potential to extend the science in the field. First, given the profound effects of obesity on physical and emotional health,[67], we have integrated physiologic and psychosocial outcomes. We have selected insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance as proximal indicators that are prelude to the development of T2D and QoL as a robust indicator of overall wellbeing. Second, we will examine short-term (3 month) and long-term (9-month) effects. This approach will support testing the efficacy of ELSC and provide details on the potential durability of changes in health outcomes after the intensive intervention period is completed. Incorporating follow-up visits in the design provides the opportunity to conduct mediation and moderation analyses which will help dissect how the intervention works and for whom. We hypothesize that enhancements in self-efficacy and social support for healthy eating and physical activity will be key mediators of changes in health behaviors and ultimately health outcomes. Further, we will explore whether sex or acculturation serve as moderators of the ELSC intervention’s effects. Understanding how interventions work and for whom will allow a more sophisticated approach to the adaptation, refinement, and tailoring of health behavior interventions.

Despite the strengths of the study, there are several limitations that are worthy of comment. These limitations include a very narrow set of inclusion criteria that will likely limit the generalizability of the findings to a very unique and high-risk population of youth. If determined to be efficacious, the approach could be adapted for other populations. Second, we acknowledge that the measures of physical activity, nutrition, and body composition are not optimal. Because our primary target is diabetes prevention, we opted for sophisticated measures of T2D risk at the expense of less than ideal measures for behavior or obesity. Lastly, we acknowledge that the sample size for the mediation and moderation analyses may be underpowered. However, to include a sufficient sample size for these exploratory aims would be cost-prohibitive under the current design.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING SOURCE:

This work is supported by the ASU Southwest Interdisciplinary Research Center, an Exploratory Center of Excellence for Health Disparities Research and Training through a grant from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (P20MD002316). The funding source did not have any role in the study design, collection, analysis and interpretation of data, the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

Trial Registration: The study is registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01236794)

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lee JM, Okumura MJ, Davis MM, Herman WH, Gurney JG. Prevalence and determinants of insulin resistance among U.S. adolescents: a population-based study. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(11):2427–32. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Menke A, Casagrande S, Cowie CC. Prevalence of Diabetes in Adolescents Aged 12 to 19 Years in the United States, 2005–2014. Jama. 2016;316(3):344–5. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.8544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goran MI, Bergman RN, Cruz ML, Watanabe R. Insulin resistance and associated compensatory responses in african-american and Hispanic children. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(12):2184–2190. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.12.2184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Narayan KM, Boyle JP, Thompson TJ, Sorensen SW, Williamson DF. Lifetime risk for diabetes mellitus in the United States. Jama. 2003;290(14):1884–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.14.1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.BeLue R, Francis LA, Colaco B. Mental health problems and overweight in a nationally representative sample of adolescents: effects of race and ethnicity. Pediatrics. 2009;123(2):697–702. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ho M, Garnett SP, Baur L, Burrows T, Stewart L, Neve M, Collins C. Effectiveness of lifestyle interventions in child obesity: systematic review with meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2012;130(6):e1647–71. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Summerbell CD, Ashton V, Campbell KJ, Edmunds L, Kelly S, Waters E. Interventions for treating obesity in children. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2003;(3):CD001872. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilson DK. New perspectives on health disparities and obesity interventions in youth. J Pediatr Psychol. 2009;34(3):231–44. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee DC, Sui X, Blair SN. Does physical activity ameliorate the health hazards of obesity? Br J Sports Med. 2009;43(1):49–51. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2008.054536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ackermann RT, Marrero DG. Adapting the Diabetes Prevention Program lifestyle intervention for delivery in the community: the YMCA model. Diabetes Educ. 2007;33(1):69, 74–5, 77–8. doi: 10.1177/0145721706297743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Economos CD, Hyatt RR, Goldberg JP, Must A, Naumova EN, Collins JJ, Nelson ME. A community intervention reduces BMI z-score in children: Shape Up Somerville first year results. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15(5):1325–36. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis JN, Ventura EE, Shaibi GQ, Byrd-Williams CE, Alexander KE, Vanni AK, Meija MR, Weigensberg MJ, Spruijt-Metz D, Goran MI. Interventions for improving metabolic risk in overweight Latino youth. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2010;5(5):451–5. doi: 10.3109/17477161003770123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kelly LA, Lane CJ, Weigensberg MJ, Toledo-Corral CM, Goran MI. Pubertal changes of insulin sensitivity, acute insulin response, and beta-cell function in overweight Latino youth. J Pediatr. 2010;158(3):442–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.08.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.A. National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Children. The fourth report on the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure in children and adolescents.[see comment] Pediatrics. 2004;114(2 Suppl 4th Report):555–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barlow SE. Expert committee recommendations regarding the prevention, assessment, and treatment of child and adolescent overweight and obesity: summary report. Pediatrics. 2007;120(Suppl 4):S164–92. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2329C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bandura A. Social Cognitive Theory. Jai Press LTD; Greenwich, CT: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benson AC, Torode ME, Fiatarone Singh MA. Effects of resistance training on metabolic fitness in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2008;9(1):43–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2007.00388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Castro FG, Barrera M, Martinez CR. The Cultural Adaptation of Prevention Interventions: Resolving Tensions Between Fidelity and Fit. Prevention Science. 2004;5(1):41–45. doi: 10.1023/b:prev.0000013980.12412.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bellg AJ, Borrelli B, Resnick B, Hecht J, Minicucci DS, Ory M, Ogedegbe G, Orwig D, Ernst D, Czajkowski S. Enhancing treatment fidelity in health behavior change studies: best practices and recommendations from the NIH Behavior Change Consortium, Health psychology: official journal of the Division of Health Psychology. American Psychological Association. 2004;23(5):443–51. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.5.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsuda M, DeFronzo RA. Insulin sensitivity indices obtained from oral glucose tolerance testing: comparison with the euglycemic insulin clamp.[see comment] Diabetes Care. 1999;22(9):1462–70. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.9.1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yeckel CW, Weiss R, Dziura J, Taksali SE, Dufour S, Burgert TS, Tamborlane WV, Caprio S. Validation of insulin sensitivity indices from oral glucose tolerance test parameters in obese children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2004;89(3):1096–101. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaufman FR. Screening for abnormalities of carbohydrate metabolism in teens. J Pediatr. 2005;146(6):721–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shaibi GQ, Davis JN, Weigensberg MJ, Goran MI. Improving insulin resistance in obese youth: choose your measures wisely. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2011;6(2-2):e290–6. doi: 10.3109/17477166.2010.528766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morales LS, Edwards TC, Flores Y, Barr L, Patrick DL. Measurement properties of a multicultural weight-specific quality-of-life instrument for children and adolescents. Qual Life Res. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9735-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patrick DL, Skalicky AM, Edwards TC, Kuniyuki A, Morales LS, Leng M, Kirschenbaum DS. Weight loss and changes in generic and weight-specific quality of life in obese adolescents. Qual Life Res. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9824-0. (In-press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pate RR, Ross R, Dowda M, Trost SG, Sirard J. Validation of a 3-Day Physical Activity Recall Instrument in Female Youth. Pediatric exercise science. 2003;15(3):257–265. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pratt C, Webber LS, Baggett CD, Ward D, Pate RR, Murray D, Lohman T, Lytle L, Elder JP. Sedentary activity and body composition of middle school girls: the trial of activity for adolescent girls. Research quarterly for exercise and sport. 2008;79(4):458–67. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2008.10599512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McMurray RG, Ring KB, Treuth MS, Welk GJ, Pate RR, Schmitz KH, Pickrel JL, Gonzalez V, Almedia MJ, Young DR, Sallis JF. Comparison of two approaches to structured physical activity surveys for adolescents. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36(12):2135–43. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000147628.78551.3b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Castro FG, Alarcon EH. Integrating cultural variables into drug abuse prevention and treatment with racial/ethnic minorities. Journal of Drug Issues. 2002;32(3):783–811. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murray-Johnson L, Witte K, Liu WY, Hubbell AP, Sampson J, Morrison K. Addressing cultural orientations in fear appeals: promoting AIDS-protective behaviors among Mexican immigrant and African American adolescents and American and Taiwanese college students. J Health Commun. 2001;6(4):335–58. doi: 10.1080/108107301317140823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marquez DX, McAuley E. Social cognitive correlates of leisure time physical activity among Latinos. J Behav Med. 2006;29(3):281–9. doi: 10.1007/s10865-006-9055-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grieser M, Neumark-Sztainer D, Saksvig BI, Lee JS, Felton GM, Kubik MY. Black, Hispanic, and white girls’ perceptions of environmental and social support and enjoyment of physical activity. J Sch Health. 2008;78(6):314–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2008.00308.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gesell SB, Reynolds EB, Ip EH, Fenlason LC, Pont SJ, Poe EK, Barkin SL. Social influences on self-reported physical activity in overweight Latino children. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2008;47(8):797–802. doi: 10.1177/0009922808318340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Hannan PJ, Tharp T, Rex J. Factors Associated With Changes in Physical Activity: A Cohort Study of Inactive Adolescent Girls. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157(8):803–810. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.8.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zeller MH, Modi AC. Predictors of health-related quality of life in obese youth. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14(1):122–30. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Norman GJ, Sallis JF, Gaskins R. Comparability and reliability of paper- and computer-based measures of psychosocial constructs for adolescent physical activity and sedentary behaviors. Research quarterly for exercise and sport. 2005;76(3):315–23. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2005.10599302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31(2):143–64. doi: 10.1177/1090198104263660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cerin E, Barnett A, Baranowski T. Testing theories of dietary behavior change in youth using the mediating variable model with intervention programs. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2009;41(5):309–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2009.03.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lubans DR, Foster C, Biddle SJ. A review of mediators of behavior in interventions to promote physical activity among children and adolescents. Prev Med. 2008;47(5):463–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goldschmidt AB, Best JR, Stein RI, Saelens BE, Epstein LH, Wilfley DE. Predictors of child weight loss and maintenance among family-based treatment completers. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2014;82(6):1140–50. doi: 10.1037/a0037169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, Lamb MM, Flegal KM. Prevalence of High Body Mass Index in US Children and Adolescents, 2007–2008. Jama. 2010;303(3):242–249. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.SfDiYSG. The Writing Group for the, Incidence of Diabetes in Youth in the United States. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2007;297(24):2716–2724. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.24.2716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bremer AA, Byrd RS, Auinger P. Differences in Male and Female Adolescents From Various Racial Groups in the Relationship Between Insulin Resistance-Associated Parameters With Sugar-Sweetened Beverage Intake and Physical Activity Levels. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 49(12):1134–1142. doi: 10.1177/0009922810379043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bauman S. The Reliability and Validity of the Brief Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican Americans-II for Children and Adolescents. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2005;27(4):426–441. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Unger JB, Gallaher P, Shakib S, Ritt-Olson A, Palmer PH, Johnson CA. The AHIMSA Acculturation Scale:: A New Measure of Acculturation for Adolescents in a Multicultural Society. The Journal of early adolescence. 2002;22(3):225–251. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Unger JB, Ritt-Olson A, Wagner K, Soto D, Baezconde L. A Comparison of Acculturation Measures Among Hispanic/Latino Adolescents. J Youth Adolesc. 2007;36:555–565. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Travers SH, Jeffers BW, Bloch CA, Hill JO, Eckel RH. Gender and Tanner stage differences in body composition and insulin sensitivity in early pubertal children. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80(1):172–178. doi: 10.1210/jcem.80.1.7829608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goodman E, Daniels SR, Dolan LM. Socioeconomic disparities in insulin resistance: results from the Princeton School District Study. Psychosomatic medicine. 2007;69(1):61–7. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000249732.96753.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bond L, Clements J, Bertalli N, Evans-Whipp T, McMorris BJ, Patton GC, Toumbourou JW, Catalano RF. A comparison of self-reported puberty using the Pubertal Development Scale and the Sexual Maturation Scale in a school-based epidemiologic survey. J Adolesc. 2006;29(5):709–720. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychol Methods. 2002;7(1):83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.kirk RE. Experimental Design. 2. Wadsworth; Monterey, CA: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Johnson P, Fay L. The Johnson-Neyman technique, its theory and application. Psychometrika. 1950;15(4):349–367. doi: 10.1007/BF02288864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Herman WH, Hoerger TJ, Brandle M, Hicks K, Sorensen S, Zhang P, Hamman RF, Ackermann RT, Engelgau MM, Ratner RE. The cost-effectiveness of lifestyle modification or metformin in preventing type 2 diabetes in adults with impaired glucose tolerance. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(5):323–32. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-5-200503010-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Haemer MA, Grow HM, Fernandez C, Lukasiewicz GJ, Rhodes ET, Shaffer LA, Sweeney B, Woolford SJ, Estrada E. Addressing prediabetes in childhood obesity treatment programs: support from research and current practice. Childhood obesity. 2014;10(4):292–303. doi: 10.1089/chi.2013.0158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Linder BL, Fradkin JE, Rodgers GP. The TODAY study: an NIH perspective on its implications for research. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(6):1775–6. doi: 10.2337/dc13-0707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Faith MS, Van Horn L, Appel LJ, Burke LE, Carson JA, Franch HA, Jakicic JM, Kral TV, Odoms-Young A, Wansink B, Wylie-Rosett J N. American Heart Association, N. Obesity Committees of the Council on, A. Physical, Metabolism, C. Council on Clinical, Y. Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the, N. Council on Cardiovascular, E. Council on, Prevention, D. Council on the Kidney in Cardiovascular. Evaluating parents and adult caregivers as “agents of change” for treating obese children: evidence for parent behavior change strategies and research gaps: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125(9):1186–207. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31824607ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.YMCA. [accessed March 25, 2011];The Y Organizational Profile. http://www.ymca.net/organizational-profile/%3E.

- 58.Marrero D. Partnering with the YMCA to Prevent Diabetes. The Obesity Society; San Diego, CA: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Adamson K, Shepard D, Easton A, JES The YMCA/Steps Community Collaboratives, 2004–2008. Prev Chronic Dis. 2009;6(3):1–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Frieden TR C. Centers for Disease, Prevention. Strategies for reducing health disparities - selected CDC-sponsored interventions, United States, 2014. Foreword, Morbidity and mortality weekly report. Surveillance summaries. 2014;63(Suppl 1):1–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Challenges and Successes in Reducing Health Disparities: Workshop Summary. The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Caprio S, Daniels SR, Drewnowski A, Kaufman FR, Palinkas LA, Rosenbloom AL, Schwimmer JB. Influence of race, ethnicity, and culture on childhood obesity: implications for prevention and treatment: a consensus statement of Shaping America’s Health and the Obesity Society. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(11):2211–21. doi: 10.2337/dc08-9024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Whitaker RC, Wright JA, Pepe MS, Seidel KD, Dietz WH. Predicting obesity in young adulthood from childhood and parental obesity. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(13):869–73. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709253371301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Balcazar H, Perez-Lizaur AB, Izeta EE, Villanueva MA. Community Health Workers-Promotores de Salud in Mexico: History and Potential for Building Effective Community Actions. The Journal of ambulatory care management. 2016;39(1):12–22. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0000000000000096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang Y, Beydoun MA, Liang L, Caballero B, Kumanyika SK. Will All Americans Become Overweight or Obese? Estimating the Progression and Cost of the US Obesity Epidemic. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2008;16(10):2323–2330. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.A. American Diabetes. Economic costs of diabetes in the U.S. in 2012. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(4):1033–46. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cheng HL, Medlow S, Steinbeck K. The Health Consequences of Obesity in Young Adulthood. Current obesity reports. 2016;5(1):30–7. doi: 10.1007/s13679-016-0190-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]