Abstract

Cancer cells consume more glucose than normal cells, mainly due to their increased rate of glycolysis. 2-Deoxy-d-glucose (2DG) is an analogue of glucose, and sorafenib is a kinase inhibitor and molecular agent used to treat hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). The present study aimed to demonstrate whether combining 2DG and sorafenib suppresses tumor cell proliferation and motility more effectively than either drug alone. HLF and PLC/PRF/5 HCC cells were incubated with sorafenib with or without 1 µM 2DG, and subjected to a proliferation assay. A scratch assay was then performed to analyze cell motility following the addition of 2DG and sorafenib in combination, and each agent alone. RNA was isolated and subjected to reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction to analyze the expression of cyclin D1 and matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP9) following the addition of 2DG and sorafenib in combination and each agent alone. Proliferation was markedly suppressed in cells cultured with 1 µM 2DG and 30 µM sorafenib compared with cells cultured with either agent alone (P<0.05). In addition, levels of Cyclin D1 expression decreased in cells exposed to 3 µM sorafenib and 1 µM 2DG compared with cells exposed to 2DG or sorafenib alone (P<0.05). Scratch assay demonstrated that the distance between the growing edge of the cell sheet and the scratched line was shorter in cells cultured with sorafenib and 2DG than in cells cultured with 2DG or sorafenib alone (P<0.05). Levels of MMP9 expression decreased more in cells treated with both sorafenib and 2DG than in cells treated with 2DG or sorafenib alone (P<0.05). Therefore, 2DG and sorafenib in combination suppressed the proliferation and motility of HCC cells more effectively than 2DG or sorafenib alone, and a cancer treatment combining both drugs may be more effective than sorafenib alone.

Keywords: 2-Deoxyglucose, sorafenib, HCC, cyclin D1, matrix metalloproteinase

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) originates in the liver following long-term infection with the hepatitis B or C virus (1), and recent research has linked non-alcoholic steatohepatitis to HCC etiology (2). Current treatments include resection, local ablation, transcatheter arterial chemoembolization, targeted chemotherapy, and palliative care (3,4). In addition, sorafenib, a kinase inhibitor, is increasingly used to treat HCC (5), however there are problems associated with its use, most notably, the ability of HCC cells to develop resistance to it (6,7).

Cancer cells depend on glycolysis for energy production and survival, and they exhibit significantly higher rates of glycolysis than healthy tissues even when oxygen is plentiful, a phenomenon known as the Warburg effect (8). As they require more glucose than healthy tissue and metabolise this glucose primarily by glycolysis, inhibiting glycolysis may be a more effective way of eradicating cancer cells (9), and consequently be developed as a treatment for cancer (10).

2-Deoxy-d-glucose (2DG) is an analogue of glucose which cannot undergo glycolysis (11). Cancer cells take up 2DG in a similar way to glucose, however, they cannot metabolize it to produce energy. Therefore energy production is impaired, and cancer cells are damaged (11).

The safety of 2DG in humans has been established through its application in positron emission tomography (12). If the combination of sorafenib and 2DG exert significantly stronger anti-tumor effects than either drug alone, it may provide a novel therapeutic strategy to treat HCC.

The present study sought to investigate the suppressive effects of sorafenib and 2DG in combination on the proliferation and motility of HCC cells compared with sorafenib alone.

Materials and methods

Cells and cell culture

Human hepatocellula carcinoma cells, HLF cells and PLC/PRF/5 cells were purchased from the RIKEN BioResource Centre Cell Bank (Tsukuba, Japan), and cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). The cells were cultured in 10 cm dishes (Asahi Techno Glass, Yoshida-cho, Japan) with 5% carbon dioxide at 37°C in a humidified chamber.

Cell proliferation assay

Cells were trypsinized, harvested, and split onto 96-well plates (Asahi Techno Glass) at a density of 1,000 cells/well. Varying concentrations of sorafenib (JS Research Chemicals Trading, Wedel, Germany), 0, 1, 3, 10, and 30 µM, were added to the media, and either 0 or 1 µM 2DG (Sigma-Aldrich) was added. Following 72 h culture, the cells were subjected to an MTS assay, (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer instructions. During the assay, the cells reduce MTS to a colored formazan product with an absorbance maximum at 490 nm. The absorbance of the product was subsequently measured using an iMark Microplate absorbance reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., Hercules, CA, USA).

Scratch assay

HLF and PLC/PRF/5 cells were plated on 4-well chamber slides (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), and scratched with a sterile razor when they reached confluence. Immediately after scratch, the cells were incubated for 48 h with 1 µM sorafenib, 3 µM 2DG, or a combination of both. Following incubation, they were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The slides were observed under an AX80 microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan, magnification ×100), and the distance between the scratched line and the growing edges of the cells was measured at five different points.

Reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Cells were cultured in 6-well plates (Asahi Techno Glass), and when they reached 70% confluence, were incubated with 1 µM sorafenib, 3 µM 2DG, or a combination of both. Following 48-h culture, RNA was isolated with Isogen (Nippon Gene Co., Tokyo, Japan) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The isolated RNA was suspended in autoclaved Tris-EDTA buffer (pH 8.0). Total RNA (5 µM) was subjected to cDNA synthesis with SuperScript III and oligo(dT) following manufacturer instructions (Thermo Fisher Scientific). RT-qPCR was performed using Fast SYBR Green Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with Mini Opticon (Bio-Rad). RT-qPCR was performed for 40 cycles, with 5 sec of denaturation and 5 sec of annealing-extension. Primer sequences are presented in Table I. RPL19, a housekeeping gene that is constitutively expressed (13), was used as an internal control. The expression levels of gene were analyzed automatically by the Mini Opticon system (Bio-Rad) based on delta-delta cycle threshold (ddCt) method. Relative expression level of a gene was calculated as expression level of a gene divided by expression level of RPL19.

Table I.

Primers for real-time quantitative PCR.

| Name | Sequence | Description | Product size, bp | Annealing temp, °C | Cycle | GenBank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OMC355 | 5′-AGAGGCGGAGGAGAACAAACAG-3′ | Cyclin D1 (F) | 180 | 60 | 40 | NM_053056 |

| OMC356 | 5′-AGGCGGTAGTAGGACAGGAAGTTG-3′ | Cyclin D1 (R) | ||||

| OMC749 | 5′-CCTGGGCAGATTCCAAACCT-3′ | MMP9 (F) | 89 | 60 | 40 | NM_004994 |

| OMC750 | 5′-GCAAGTCTTCCGAGTAGTTTTGGAT-3 | MMP9 (R) | ||||

| OMC321 | 5′-CGAATGCCAGAGAAGGTCAC-3′ | RPL19 (F) | 157 | 60 | 40 | BC095445 |

| OMC322 | 5′-CCATGAGAATCCGCTTGTTT-3′ | RPL19 (R) |

F, forward; R, reverse.

Statistical analysis

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for statistical analysis with JMP software ver. 10.0.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

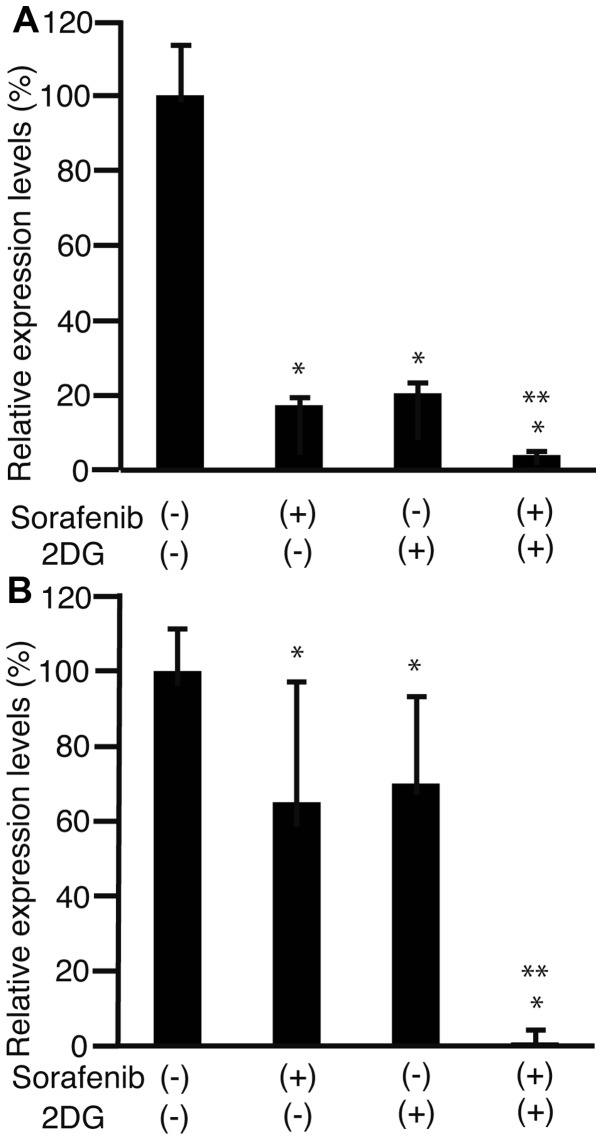

To investigate whether 2DG enhanced the anti-proliferative effects of sorafenib, HLF cells (Fig. 1A) and PLC/PRF/5 cells (Fig. 1B) were cultured with 0, 1, 3, 10, and 30 µM sorafenib either alone (black bars) or with 2DG (white bars). The combination of 1 µM 2DG and 30 µM sorafenib markedly suppressed cell proliferation of both cell types compared to sorafenib alone (P<0.05). This suggests that 2DG is able able to enhance the anti-proliferative effects of sorafenib in HLF and PLC/PRF/5 cells.

Figure 1.

Cell proliferation assay. HLF cells (A) and PLC/PRF/5 cells (B) were added to 0, 1, 3, 10, and 30 µM sorafenib either with (white bar), or without (black bar) 1 µM 2DG. The cells were subjected to MTS assay to measure cell proliferation. *P<0.05 against 0 µM 2DG and sorafenib, **P<0.05 against 0 µM 2DG and 30 µM sorafenib. HLF, Human liver fibroblasts; PLC/PRF/5, the human PLC/PRF/5 hepatoma carcinoma cell line; 2DG, 2-deoxy-glucose.

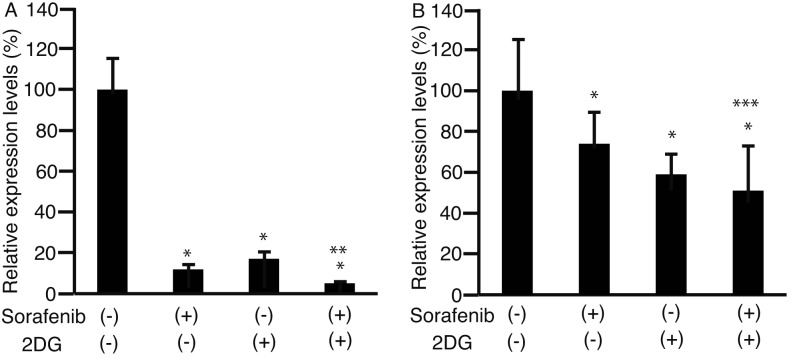

To clarify the effect of sorafenib and 2DG on the cell cycle, levels of cyclin D1 expression were analyzed by RT-qPCR in HLF cells (Fig. 2A) and PLC/PRF/5 cells (Fig. 2B). The expression of cyclin D1 in both cell types decreased more in cells exposed to sorafenib and 2DG compared with cells exposed to 2DG or sorafenib alone (P<0.05; Fig. 2). This demonstrates that sorafenib and 2DG together decrease cyclin D1 expression more effectively than either drug alone.

Figure 2.

Levels of cyclin D1 expression. HLF cells (A) and PLC/PRF/5 cells (B) were cultivated with 3 µM sorafenib, 1 µM 2DG, or a combination of the two. Cyclin D1 expression levels were compared with those of a control containing cells without sorafenib or 2DG. RNA was isolated and subjected to RT-qPCR to analyze cyclin D1 expression. *P<0.05 against sorafenib (−) and 2DG (−) **P<0.05 against sorafenib (−) and 2DG (−), sorafenib (−) and 2DG (+), and sorafenib (+) and 2DG (−), n=3. HLF cells, human liver fibroblast cells; PLC/PRF/5, the human hepatoma carcinoma cell line; 2DG, 2-deoxy-glucose; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction.

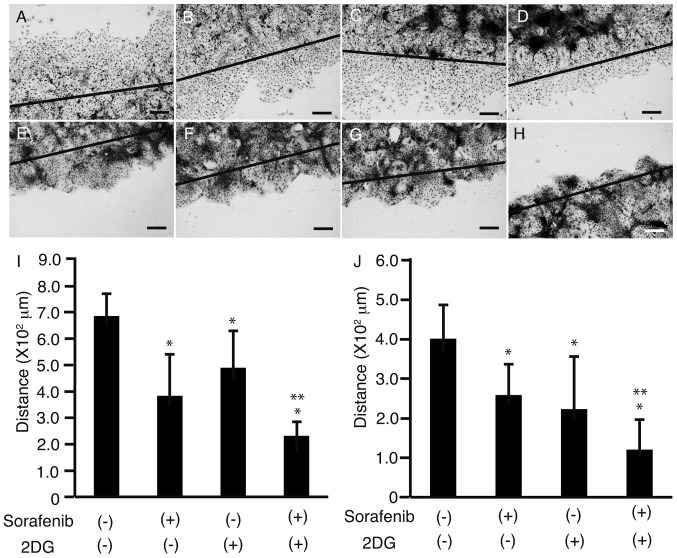

To investigate the effects of sorafenib and 2DG on cell motility, a scratch assay was performed on HLF cells (Fig. 3A-D) and PLC/PRF/5 cells (Fig. 3E-H). All cells were cultured in 4-well chamber slides, and following scratching with a sterile razor, 3 µM sorafenib (Fig. 3B and F), 1 µM 2DG (Fig. 3C and G), or a combination of both (Fig. 3D and H) were added. Cells were then stained, and the distance between the growing edge of the cell sheet and the scratched line was measured in HLF cells (Fig. 3I) and PLC/PRF/5 cells (Fig. 3J). The distance was shorter in cells cultured with both sorafenib and 2DG than in cells cultured with 2DG or sorafenib alone (P<0.05; Fig. 3I and J), suggesting that 2DG enhances the suppressive effects of sorafenib on cell motility.

Figure 3.

Scratch assay. HLF cells (A-D) and PLC/PRF/5 cells (E-H) in 4-well chamber slides were scratched with a sterile razor. Immediately after the scratch (solid line), no sorafenib or 2DG (A, E), 3 µM sorafenib (B, F), 1 µM 2DG (C, G), or both (D, H) were added to the cells. Following 48 h in culture, the cells were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Distance between the growing edge of the cell sheet and the scratched line was measured at five different points in HLF cells (I) and PLC/PRF/5 cells (J). Original magnification: ×100, scale bar: 200 µM, *P<0.05 against sorafenib (−) and 2DG (−), **P<0.05 against sorafenib (−) and 2DG (−), sorafenib (−) and 2DG (+), and sorafenib (+) and 2DG (−), n=5. HLF, Human liver fibroblast cells; 2DG, 2-deoxyglucose; PLC/PRF/5 cells, human hepatoma carcinoma cell line.

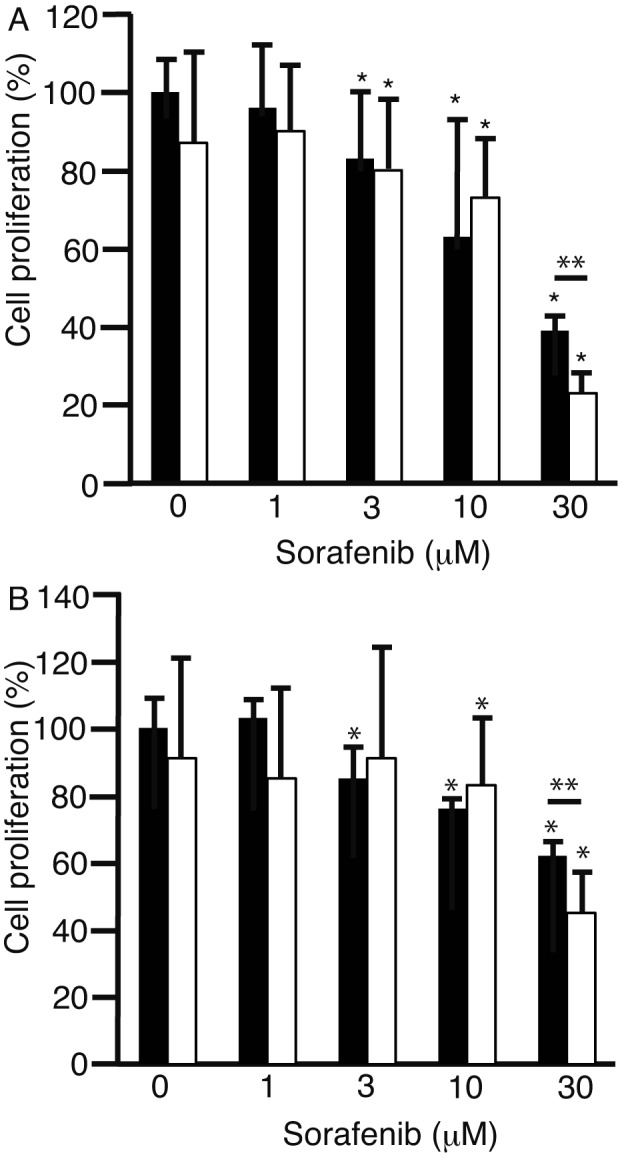

Matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9) is involved in cell motility and is overexpressed in HCC (14,15). MMP9 expression was analyzed using RT-qPCR in HLF cells (Fig. 4A) and PLC/PRF/5 cells (Fig. 4B), and was significantly lower in cells cultured with a combination of sorafenib and 2DG than in cells cultured with either drug alone (P<0.05).

Figure 4.

Expression levels of matrix metalloproteinase. HLF cells (A) and PLC/PRF/5 cells (B) were cultured in 6-well plates, and added to 3 µM sorafenib (+), 1 µM 2DG (+), or a combination of both. Following 48 h in culture, RNA was isolated and subjected to RT-qPCR. Levels of matrix metalloproteinase expression were analyzed. *P<0.05 against sorafenib (−) and 2DG (−), **P<0.05 against sorafenib (−) and 2DG (−), sorafenib (−) and 2DG (+), and sorafenib (+) and 2DG (−), ***P<0.05 against sorafenib (−) and 2DG (−), and sorafenib (−) and 2DG (+), n=3. HLF, Human liver fibroblast cells; 2DG, 2-deoxyglucose; PLC/PRF/5 cells, human hepatoma carcinoma cell line; RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction.

Discussion

Previous studies have demonstrated that 2-[(3-Carboxy- 1-oxoprogy1) amino]-2-deoxy-D-glucose, another analogue of glucose similar to 2DG, suppresses the proliferation of cells from the human HCC HepG2 cell line (16). In the present study, 3 µM 2DG and 30 µM sorafenib significantly suppressed the proliferation of HLF and HCC PLC/PRF/5 cells. The difference in suppression of proliferation was significant at sorafenib concentrations >10 µM.

Sorafenib and 2DG independently decrease cyclin D1 expression (Fig. 2), therefore it was expected that the combination of sorafenib and 2DG would synergistically suppress HCC proliferation at lower concentrations of sorafenib. This was observed in both HLF and PLC/PRF/5 cells. However, the reasons underlying the suppressive effects of 2DG and sorafenib combination on HCC cell proliferation remain unclear.

Metastasis is a result of HCC cell invasion from the primary site to local or distant tissue (17). The combination of 2DG and sorafenib suppressed cell motility more effectively than 2DG or sorafenib alone (Fig. 3). Additionally, expression of MMP9 significantly decreased when cells were treated with a combination of 2DG and sorafenib compared with 2DG or sorafenib alone (Fig. 4), suggesting that treatment with both 2DG and sorafenib may effectively inhibit metastasis.

2DG enhances the anti-tumor effects of other chemotherapeutic agents (18). In vivo studies have demonstrated that sections of tumors are hypoxic (19), and cancer cells are resistant to 2DG in these hypoxic regions (20). The combination of 2DG and sorafenib offers a promising strategy to overcome this resistance.

The feasibility of this approach is contingent on 2DG and sorafenib being safe for oral administration. A combination of 2DG and docetaxel as treatment for solid cancers has been investigated, and no serious adverse effects were reported (21). Furthermore, a phase I/II clinical trial investigating the combination of radiotherapy and 2DG against glioma reported no serious adverse events (22). These reports and the results of the current study suggest that the combination of 2DG and sorafenib is safe for oral administration, though further studies are required to confirm this.

The main limitation of the present study was the lack of in vivo data from xenograft animal models, therefore future studies are required that investigate the effects of systemic 2DG and sorafenib administration in vivo.

In conclusion, the current study demonstrated that 2DG and sorafenib suppressed the proliferation of HCC cells more effectively than sorafenib alone, and suppressed cell motility more effectively than 2DG or sorafenib alone. Therefore, combined treatment of 2DG and sorafenib may be an effective therapeutic strategy to treat cancer, including HCC.

References

- 1.Cameron AM. Screening for viral hepatitis and hepatocellular cancer. Surg Clin North Am. 2015;95:1013–1021. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2015.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khan FZ, Perumpail RB, Wong RJ, Ahmed A. Advances in hepatocellular carcinoma: Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis-related hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Hepatol. 2015;7:2155–2161. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v7.i18.2155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wells SA, Hinshaw JL, Lubner MG, Ziemlewicz TJ, Brace CL, Lee FT., Jr Liver ablation: Best practice. Radiol Clin North Am. 2015;53:933–971. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2015.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katano T, Mizoshita T, Senoo K, Sobue S, Takada H, Sakamoto T, Mochiduki H, Ozeki T, Kato A, Matsunami K, et al. The efficacy of transcatheter arterial embolization as the first-choice treatment after failure of endoscopic hemostasis and endoscopic treatment resistance factors. Dig Endosc. 2012;24:364–369. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2012.01285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Furuse J, Ishii H, Nakachi K, Suzuki E, Shimizu S, Nakajima K. Phase I study of sorafenib in Japanese patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Sci. 2008;99:159–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00648.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuczynski EA, Lee CR, Man S, Chen E, Kerbel RS. Effects of sorafenib dose on acquired reversible resistance and toxicity in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2015;75:2510–2519. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-3687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen J, Jin R, Zhao J, Liu J, Ying H, Yan H, Zhou S, Liang Y, Huang D, Liang X, et al. Potential molecular, cellular and microenvironmental mechanism of sorafenib resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2015;367:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vaitheesvaran B, Xu J, Yee J, Qy L, Go VL, Xiao GG, Lee WN. The Warburg effect: A balance of flux analysis. Metabolomics. 2015;11:787–796. doi: 10.1007/s11306-014-0760-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jang M, Kim SS, Lee J. Cancer cell metabolism: Implications for therapeutic targets. Exp Mol Med. 2013;45:e45. doi: 10.1038/emm.2013.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Granja S, Pinheiro C, Reis RM, Martinho O, Baltazar F. Glucose addiction in cancer therapy: Advances and drawbacks. Curr Drug Metab. 2015;16:221–242. doi: 10.2174/1389200216666150602145145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang D, Li J, Wang F, Hu J, Wang S, Sun Y. 2-Deoxy- D-glucose targeting of glucose metabolism in cancer cells as a potential therapy. Cancer Lett. 2014;355:176–183. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brito AF, Mendes M, Abrantes AM, Tralhão JG, Botelho MF. Positron emission tomography diagnostic imaging in multidrug-resistant hepatocellular carcinoma: Focus on 2-deoxy-2-(18F)Fluoro-D-Glucose. Mol Diagn Ther. 2014;18:495–504. doi: 10.1007/s40291-014-0106-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davies B, Fried M. The L19 ribosomal protein gene (RPL19): Gene organization, chromosomal mapping, and novel promoter region. Genomics. 1995;25:372–380. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(95)80036-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vandooren J, Van den Steen PE, Opdenakker G. Biochemistry and molecular biology of gelatinase B or matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9): The next decade. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2013;48:222–272. doi: 10.3109/10409238.2013.770819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Y, Shen Y, Cao B, Yan A, Ji H. Elevated expression levels of androgen receptors and matrix metalloproteinase-2 and −9 in 30 cases of hepatocellular carcinoma compared with adjacent tissues as predictors of cancer invasion and staging. Exp Ther Med. 2015;9:905–908. doi: 10.3892/etm.2014.2150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu J, Kou W, Gao MT, Zhou YN, Wang AQ, Xue QJ, Qiao L. Effects of {2-[(3-carboxy-1-oxoprogy1)amino]-2-deoxy-D-glucose} on human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2005;26:635–640. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2005.00066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tomizawa M, Kondo F, Kondo Y. Growth patterns and interstitial invasion of small hepatocellular carcinoma. Pathol Int. 1995;45:352–358. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1995.tb03468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takemura A, Che XF, Tabuchi T, Moriya S, Miyazawa K, Tomoda A. Enhancement of cytotoxic and pro-apoptotic effects of 2-aminophenoxazine-3-one on the rat hepatocellular carcinoma cell line dRLh-84, the human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line HepG2, and the rat normal hepatocellular cell line RLN-10 in combination with 2-deoxy-D-glucose. Oncol Rep. 2012;27:347–355. doi: 10.3892/or.2011.1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lv Y, Zhao S, Han J, Zheng L, Yang Z, Zhao L. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α induces multidrug resistance protein in colon cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2015;8:1941–1948. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S82835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maher JC, Wangpaichitr M, Savaraj N, Kurtoglu M, Lampidis TJ. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 confers resistance to the glycolytic inhibitor 2-deoxy-D-glucose. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:732–741. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raez LE, Papadopoulos K, Ricart AD, Chiorean EG, Dipaola RS, Stein MN, Lima CM Rocha, Schlesselman JJ, Tolba K, Langmuir VK, et al. A phase I dose-escalation trial of 2-deoxy-D-glucose alone or combined with docetaxel in patients with advanced solid tumors. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2013;71:523–530. doi: 10.1007/s00280-012-2045-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singh D, Banerji AK, Dwarakanath BS, Tripathi RP, Gupta JP, Mathew TL, Ravindranath T, Jain V. Optimizing cancer radiotherapy with 2-deoxy-d-glucose dose escalation studies in patients with glioblastoma multiforme. Strahlenther Onkol. 2005;181:507–514. doi: 10.1007/s00066-005-1320-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]