Abstract

Peroxiredoxins (PRDXs) are a ubiquitously expressed family of small (22–27 kDa) non-seleno peroxidases that catalyze the peroxide reduction of H2O2, organic hydroperoxides and peroxynitrite. They are highly involved in the control of various physiological functions, including cell growth, differentiation, apoptosis, embryonic development, lipid metabolism, the immune response, as well as cellular homeostasis. Although the protective role of PRDXs in cardiovascular and neurological diseases is well established, their role in cancer remains controversial. Increasing evidence suggests the involvement of PRDXs in carcinogenesis and in the development of drug resistance. Numerous types of cancer cells, in fact, are characterized by an increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, and often exhibit an altered redox environment compared with normal cells. The present review focuses on the complex association between oxidant balance and cancer, and it provides a brief account of the involvement of PRDXs in tumorigenesis and in the development of chemoresistance.

Keywords: peroxiredoxins, oxidative stress, tumorigenesis, chemoresistance, chemosensitization

1. Oxidative stress and the role of H2O2 as a second messenger

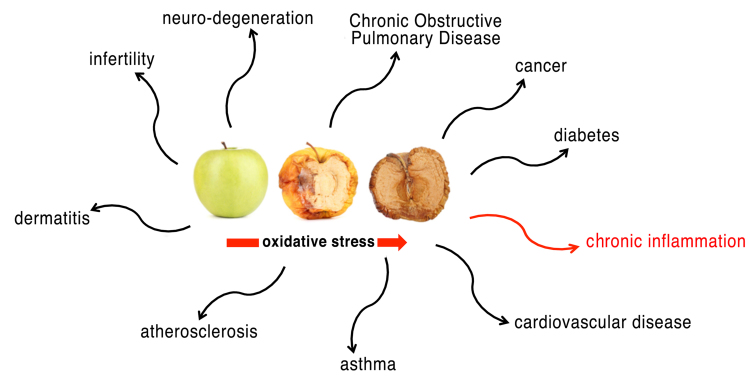

Life in an oxygen-rich environment has to deal with the danger of oxidative stress. Oxidative stress represents a biochemical state characterized by an excessive presence of free radicals and reactive metabolites potentially harmful for the organism (1,2). Free radicals are highly reactive chemical species, typically with a short half-life, consisting of an atom or a molecule containing one or more unpaired electrons. These electrons give a significant reactivity to the radical, making it able to bind to other radicals or subtract an electron from other molecules nearby. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are the most important class of free radicals that are produced by organisms: Elevated levels result from an imbalance between the production of oxidants and their elimination by the antioxidant system protecting the organism. The superoxide anion radical (O2=) is one of the best known ROS. Its metabolites, such as the hydroxyl radical (•OH) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), are very reactive (3). Reactive nitrogen species (RNS) are another family of free radicals (with antimicrobial action), derived from nitric oxide (•NO) and superoxide anion (O2=), that, acting together with ROS, can damage cells. Not surprisingly, in humans, associations between the level of oxidative stress and serious diseases, including diabetes mellitus, atherosclerosis, hypertension, inflammatory diseases, neurodegenerative disorders and cancer, are well known (1,2,4) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Oxidative stress and human diseases. Oxidative stress plays a role in many pathological processes.

During normal cell metabolism, the production of ATP by aerobic respiration in mitochondria constantly produces ROS and RNS, such as the by-products of oxidative phosphorylation.

At low to moderate concentrations, ROS exert an important positive role in several physiological processes, including defense against infectious agents and cell signaling (5), although at high concentrations they are able to react with many cellular components, such as nucleic acids, proteins and lipids, causing DNA damage that escapes the DNA repair system. For this reason, their concentration needs to be strictly controlled. In numerous organisms, ROS, and especially H2O2, are signaling molecules able to cross the membranes, to function as second messengers inside the cell, and to induce specific signal transduction pathways. Furthermore, ROS and RNS are able to control the activity of enzymes by triggering several post-translational modifications, such as disulfide bond formation, thiol oxidation to sulfenic/sulfinic/sulfonic acid, glutathionylation, nitrosylation and carbonylation. Several studies have reported that cell stimulation by a variety of growth factors, cytokines and G-protein-coupled receptors generates intracellular H2O2, e.g. (6), so that it may be difficult to resolve whether the cell is being subjected to H2O2-dependent signaling or to oxidative stress. Aerobic organisms are equipped with nonenzymatic (ascorbate, glutathione, tocopherol and carotenoid) or enzymatic [catalase (CAT), ascorbate peroxidase, superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione peroxidase (GPx) and peroxiredoxin] antioxidant systems to neutralize ROS and RNS in the cells and to finely control their concentrations.

2. A special class of antioxidant enzymes: The peroxiredoxins

One of the most important enzyme systems that, together with SOD, CAT and GPx, act in the defense against oxidative stress is the “peroxiredoxin” (PRDX) family (7,8).

PRDXs have been identified in numerous organisms and constitute a ubiquitous family of thiol-dependent peroxidases, catalyzing the reduction of H2O2, alkyl hydroperoxides and peroxynitrite to water, the corresponding alcohol and nitrite, respectively (9–11), emerging as arguably the most important and widespread peroxide and peroxynitrite scavenging enzymes in all of biology (12,13). Their role was long overshadowed by well-studied oxidative stress defense enzymes such as catalase and glutathione peroxidase, considered for a long time to be the major enzymes responsible for protecting cells against hydroperoxides.

Unlike heme-dependent catalase and the selenium-dependent glutathione peroxidase, PRDXs do not require cofactors. They were identified approximately 27 years ago in yeast (14) and 25 years ago in mammals (15), and are functionally conserved in all three phylogenetic domains: Archaea, Bacteria and Eukaryota, stressing the importance of the existence of systems protecting against ROS for the evolution of living organisms (16) (Table I).

Table I.

PRDXs are functionally conserved in all three phylogenetic domains.a

| Identity (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Species | Gene symbol | Protein | DNA |

| H. sapiens PRDX1 | |||

| vs. P. troglodytes | PRDX1 | 100.0 | 99.7 |

| vs. M. mulatta | PRDX1 | 99.5 | 98.5 |

| vs. C. lupus | PRDX1 | 99.0 | 93.3 |

| vs. B. taurus | PRDX1 | 96.5 | 93.6 |

| vs. M. musculus | Prdx1 | 95.5 | 90.8 |

| vs. R. norvegicus | Prdx1 | 97.5 | 91.3 |

| vs. R. norvegicus | Prdx1l1 | 97.0 | 91.3 |

| vs. G. gallus | PRDX1 | 88.4 | 78.7 |

| vs. X. tropicalis | LOC101731384 | 84.9 | 76.2 |

| vs. X. tropicalis | Prdx1 | 84.9 | 76.0 |

| vs. D. rerio | Prdx1 | 81.3 | 73.9 |

| H. sapiens PRDX2 | |||

| vs. P. troglodytes | PRDX2 | 100.0 | 99.8 |

| vs. M. mulatta | PRDX2 | 100.0 | 98.1 |

| vs. C. lupus | PRDX2 | 93.4 | 88.2 |

| vs. B. taurus | PRDX2 | 91.2 | 87.4 |

| vs. M. musculus | prdx2 | 93.4 | 88.2 |

| vs. R. norvegicus | prdx2 | 93.4 | 87.0 |

| vs. X. tropicalis | prdx3 | 79.6 | 70.7 |

| vs. X. tropicalis | prdx2 | 77.5 | 72.4 |

| vs. D. rerio | prdx2 | 76.6 | 72.8 |

| vs. D. melanogaster | Jafrac1 | 71.3 | 67.4 |

| vs. A. gambiae | TPX2 | 68.1 | 66.0 |

| vs. C. elegans | prdx2 | 73.2 | 66.7 |

| vs. S. cerevisiae | TSA1 | 66.8 | 61.1 |

| vs. S. pombe | tpx1 | 68.8 | 60.8 |

| vs. A. thaliana | 2Cys Prx B | 63.8 | 61.2 |

| vs. A. thaliana | AT3G11630 | 64.4 | 61.3 |

| vs. O. sativa | Os02g0537700 | 62.2 | 61.5 |

| H. sapiens PRDX3 | |||

| vs. P. troglodytes | PRDX3 | 100.0 | 99.6 |

| vs. M. mulatta | PRDX3 | 97.7 | 97.5 |

| vs. C. lupus | PRDX3 | 91.4 | 88.2 |

| vs. B. taurus | PRDX3 | 89.1 | 88.8 |

| vs. M. musculus | Prdx3 | 86.3 | 84.2 |

| vs. R. norvegicus | Prdx3 | 85.2 | 83.2 |

| vs. G. gallus | PRDX3 | 79.2 | 71.7 |

| vs. M. mulatta | LOC719764 | 99.2 | 97.8 |

| vs. D. rerio | prdx3 | 75.4 | 66.8 |

| vs. D. melanogaster | Prx3 | 64.5 | 61.7 |

| vs. A. gambiae | TPX1 | 63.9 | 58.6 |

| vs. C. elegans | prdx3 | 66.8 | 60.4 |

| vs. S. cerevisiae | TSA2 | 57.3 | 57.1 |

| vs. K. lactis | KLLA0B01628g | 56.8 | 58.7 |

| vs. E. gossypii | AGOS_AER312W | 57.8 | 59.5 |

| H. sapiens PRDX4 | |||

| vs. M. mulatta | PRDX4 | 98.5 | 98.4 |

| vs. C. lupus | PRDX4 | 93.0 | 89.2 |

| vs. B. taurus | PRDX4 | 93.8 | 90.8 |

| vs. M. musculus | Prdx4 | 95.0 | 89.1 |

| vs. R. norvegicus | Prdx4 | 94.5 | 90.3 |

| vs. G. gallus | PRDX4 | 91.9 | 81.6 |

| vs. X. tropicalis | prdx4 | 93.6 | 81.1 |

| vs. D. rerio | prdx4 | 88.7 | 74.8 |

| vs. D. melanogaster | Jafrac2 | 71.0 | 64.4 |

| vs. A. gambiae | TPX3 | 74.7 | 65.9 |

| H. sapiens PRDX5 | |||

| vs. P. troglodytes | PRDX5 | 99.5 | 99.7 |

| vs. B. taurus | PRDX6 | 95.1 | 92.9 |

| vs. C. lupus | PRDX5 | 85.5 | 84.9 |

| vs. B. taurus | PRDX5 | 81.9 | 83.8 |

| vs. M. musculus | Prdx5 | 87.2 | 86.1 |

| vs. R. norvegicus | Prdx5 | 88.1 | 85.3 |

| vs. X. tropicalis | prdx5 | 67.3 | 65.2 |

| vs. D. rerio | prdx5 | 61.3 | 64.0 |

| vs. D. melanogaster | Prdx5 | 59.5 | 62.4 |

| vs. A. gambiae | AgaP_AGAP | 60.0 | 60.9 |

| 001325 | |||

| vs. K. lactis | KLLA0A07271g | 39.3 | 46.8 |

| vs. E. gossypii | AGOS_ADL154C | 40.5 | 48.4 |

| vs. S. pombe | SPCC330.06c | 35.3 | 42.7 |

| vs. M. oryzae | MGG_00860 | 44.4 | 53.0 |

| vs. N. crassa | NCU06880 | 44.1 | 52.8 |

| vs. A. thaliana | AT1G60740 | 42.7 | 49.7 |

| vs. A. thaliana | TPX1 | 43.9 | 50.5 |

| vs. A. thaliana | TPX2 | 42.7 | 49.7 |

| vs. O. sativa | Os01g0675100 | 44.0 | 49.9 |

| H. sapiens PRDX6 | |||

| vs. P. troglodytes | PRDX6 | 100.0 | 99.7 |

| vs. M. mulatta | PRDX6 | 98.7 | 98.4 |

| vs. C. lupus | PRDX6 | 92.9 | 91.5 |

| vs. M. musculus | Prdx6 | 89.7 | 87.4 |

| vs. R. norvegicus | Prdx6 | 91.5 | 88.8 |

| vs. G. gallus | PRDX6 | 86.4 | 78.0 |

| vs. X. tropicalis | prdx6 | 76.9 | 71.0 |

| vs. D. rerio | prdx6 | 73.6 | 67.3 |

| vs. D. melanogaster | Prx6005 | 61.0 | 58.9 |

| vs. A. gambiae | TPX5 | 60.2 | 59.7 |

| vs. C. elegans | prdx6 | 52.4 | 55.6 |

| vs. S. cerevisiae | PRX1 | 51.0 | 54.8 |

| vs. K. lactis | KLLA0E20285g | 48.6 | 54.6 |

| vs. E. gossypii | AGOS_AGR368W | 50.5 | 55.4 |

| vs. M. oryzae | MGG_08256 | 53.5 | 58.1 |

| vs. N. crassa | NCU06031 | 53.3 | 58.7 |

| vs. A. thaliana | PER1 | 52.6 | 55.8 |

| vs. O. sativa | Os07g0638300 | 53.5 | 59.3 |

| vs. O. sativa | Os07g0638400 | 53.9 | 56.5 |

Homologs of the PRDX genes are listed in the Table. In the figure the Pairwise Alignment Scores and evolutionary distances have been reported (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/). PRDX, peroxiredoxin; TPX, thiol peroxidase.

PRDXs have been classified into the following subgroups on the basis of functional site sequence similarity (17): Prx1/PRDX1, Prx5/PRDX5 and Prx6/PRDX6 (18). The phylogenetic distribution of PRDXs demonstrates the widest biological distribution for the Prx1/PRDX1 and Prx6/PRDX6 subfamilies; Prx5/PRDX5 members are apparently lost in archaea (Table I).

PRDXs of different subgroups vary in their oligomerization states, conformational flexibility, and certain secondary structural elements. In addition, most organisms possess multiple isoforms (19): In humans, for example, six different isoforms of PRDX are present (20), four PRDX1 subtypes, one PRDX5 subtype and one PRDX6 subtype.

PRDX1, PRDX2, PRDX3, PRDX5 and PRDX6 are localized in the cytosol, in the mitochondria, in the nuclei and in the peroxisomes (21–23), whereas PRDX4 is mainly present in the endoplasmic reticulum, or it is secreted (24).

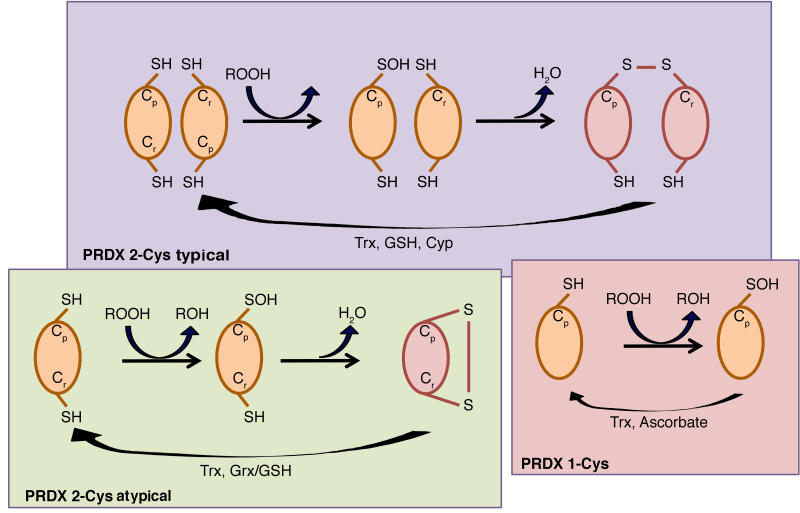

The catalytic activity of PRDXs is crucially dependent on a conserved peroxidatic Cys (Cp) residue contained within a universally conserved Pxxx(T/S)xxC active-site motif in the amino-terminal portion of the protein (17), which corresponds to Cys-47 in yeast cytosolic thioredoxin peroxidase I (cTPx I) (15). Five out of six human PRDXs also contain an additional conserved Cys in the carboxy-terminal region, which corresponds to Cys-170 in yeast thiol-specific antioxidant (TSA) (15), termed resolving cysteine (Cr). Depending on the PRDX, the Cr may be located within the same chain of Cp or in the chain of another subunit, therefore human PRDXs are classified into three classes: i) Typical 2-Cys PRDXs, which include PRDX1-4, ii) atypical 2-Cys PRDX and PRDX5, and iii) 1-Cys PRDX and PRDX6 (25). The typical 2-Cys PRDXs are obligate homodimers containing two identical active sites, bringing the two redox-active cysteines (Cp and Cr) into close proximity (26). By contrast, atypical 2-Cys PRDXs form an intramolecular disulfide intermediate by reacting the amino-terminal sulfenic acid (Cys-47) with a carboxy-terminal Cys-SH (Cys-151) of the same molecule that is able to be reduced by thioredoxin (27).

PRDX6 is the only known mammalian member of the 1-Cys subgroup. The mechanism by which its sulfenic acid form is reduced has yet to be fully elucidated (27), but Monteiro et al (28) have unequivocally demonstrated that 1-Cys PRDXs are reduced by ascorbate (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Mechanisms of the three PRDX subtypes. In typical 2-Cys PRDXs, the main cysteine residue (Cp) reacts with the residue Cr on the second subunit of the dimer. In atypical 2-Cys PRDXs, the oxidized Cp reacts with the Cr residue located in the same molecule. In 1-Cys PRDXs, the Cp residue generates sulfenic acid and is regenerated directly through donation of an electron to the thiol form in presence of ascorbate. Cyp, cyclophilin; Grx, glutaredoxin; GSH, reduced glutathione; ROOH, peroxide; Cp, peroxidatic Cys; Cr, resolving cysteine; Trx, thioredoxin.

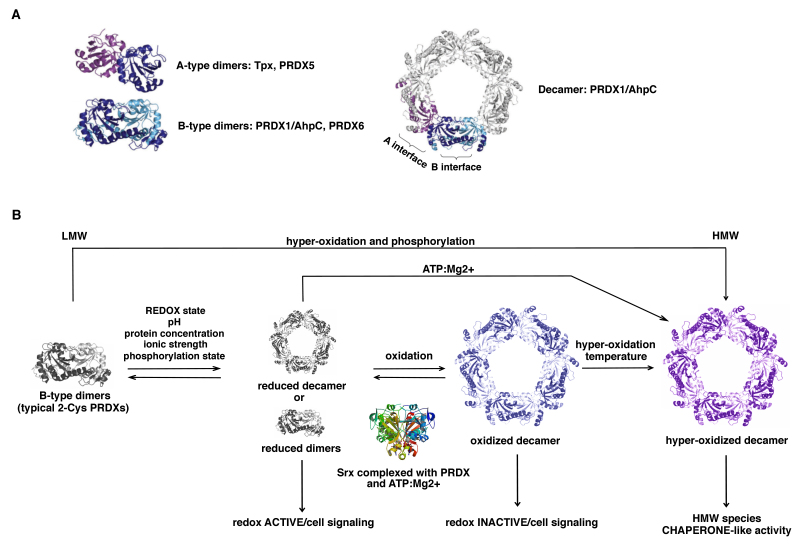

Members of the Prx1/PRDX1 and Prx6/PRDX6 subfamilies dimerize using the ‘B interface’ (denoting the β-strand interactions) to form an extended 10 to 14-strand β-sheet (29) (Fig. 3), whereas members of the Prx5/PRDX5 subfamily typically dimerize and associate across the ‘A interface’ (denoting either ‘alternate’ or ‘ancestral’). In addition, a large number of PRDXs that form dimers across their B interface can show a further redox-sensitive dependent oligomerization to form octamers, decamers or dodecamers across their A interface (19).

Figure 3.

Quaternary structure of PRDXs. (A) A-type dimers or B-type dimers. Certain components of the PRDX1 and PRDX6 subfamilies form a decameric structure through the interaction of five B-type dimers via the A-type dimer interface (A-type dimer colored in purple/blue; B-type dimer colored in blue/light blue). (B) The model of typical 2-Cys PRDX oligomerization and function: Different factors induce oligomerization of the dimers to hexa-, octa-, decamers or higher-order aggregates that are able to function as a peroxidase. Oxidation leads to the breakdown of the decamers, whereas hyperoxidation stabilizes the oligomer. Oxidized decamers can be reversed by sulfiredoxin (Srx) reduction (167). Hyperoxidized decamers are stable HMW complexes with chaperone-like activity. LMW, low molecular weight; HMW, high-molecular-weight; PRDX, peroxiredoxin.

Typical 2-Cys PRDXs (PRDX1-4) form decamers or dodecamers in the reduced or hyperoxidized state, acquiring the ability to exercise other functions as chaperones, binding partners, enzyme activators and/or redox sensors, while the oxidized form is preferentially present as dimers (30) (Fig. 3). Atypical 2-Cys PRDXs are able to undergo protein-protein interactions with functional implications, although their level of polymerization is less compared with that of typical 2-Cys PRDXs.

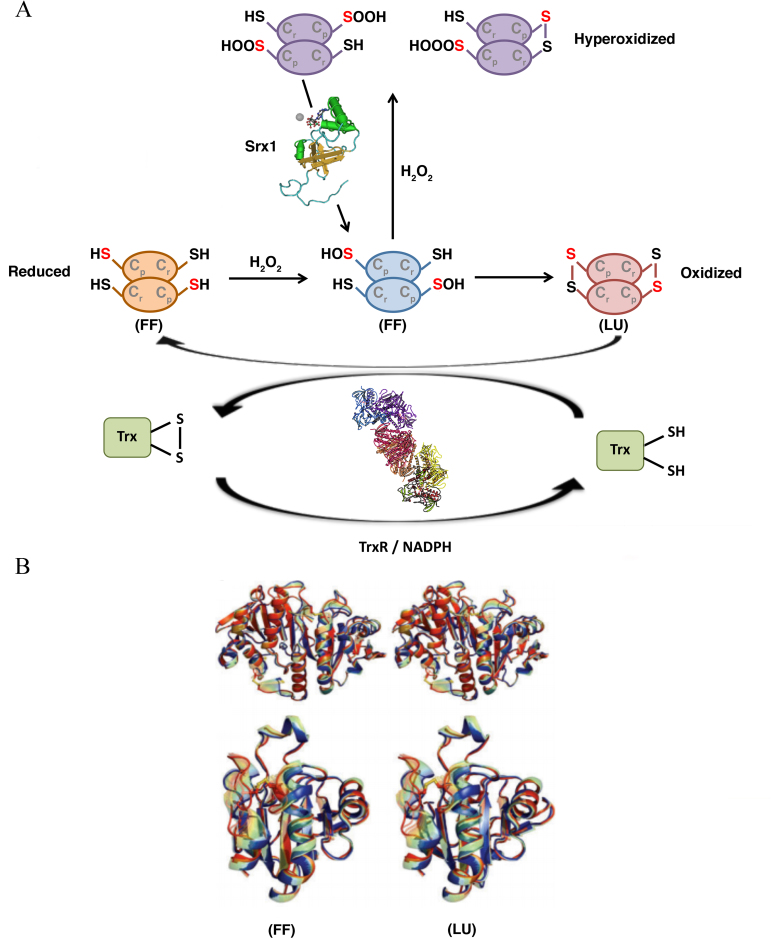

By contrast, 1-Cys PRDXs are not able to form decamers, and this is probably the reason why they serve mainly an antioxidant function rather than a molecular chaperone function, despite their enzymatic mechanism being very similar to that of 2-Cys PRDXs (31). Concerning the catalytic function, PRDXs tune the sensitivity to hyperoxidation switching from a fully folded (FF) conformation, in which Cp can react with the peroxide, to a locally unfolded (LU) conformation, in which the Cp is exposed and can form a disulfide bridge with the Cr (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Catalytic mechanism of typical 2-Cys PRDXa. (A) PRDXs switch from an FF conformation, in which Cp reacts with the peroxide, to an LU conformation, in which the Cp is exposed and forms a disulfide bridge with the Cr residue. The thiol groups are converted into sulfenic acid (−S-OH) and form disulfide bonds with other thiol groups (−SS-) (oxidized status-LU conformation). At high peroxide concentrations, the sulfenic acid intermediate is overoxidized to sulfinic acid (−SOOH) or even sulfonic acid (−SOOOH), causing the inactivation of the enzyme (hyperoxidized status). (B) Stereo-view of the interpolated structural changes shown in rainbow colors between the FF (blue) and LU (red) conformations for a representative of Prx1 subfamily (upper) and Prx5 subfamily (lower). PRDX, peroxiredoxin; Srx1 sulfiredoxin 1, Trx, thioredoxin; TrxR, thioredoxin reductase; FF, fully folded; LU, locally unfolded.

PRDXs are highly involved in the control of cellular physiological functions, including growth, differentiation, apoptosis, embryonic development, lipid metabolism, the immune response, as well in the maintenance of cellular homeostasis (32) (Fig. 5). Over the course of the last few years, a large body of evidence has suggested their involvement in carcinogenesis and in the development of drug resistance. This review focuses on the complex relationships between oxidant balance and cancer, and it provides a brief account of the involvement of PRDXs in tumorigenesis and in the development of chemoresistance.

Figure 5.

WordCloud for PRDXs. The WordCloud representation shows the majority information about the PRDX family (see http://www.maayanlab.net/G2W/help.php). PRDX, peroxiredoxin.

3. ROS stress in cancer cells

ROS, such as the superoxide radical, the hydroxyl radical and H2O2 or RNS, such as peroxynitrites and nitrogen oxides, are toxic metabolic secondary products that pose a significant threat by damaging DNA, lipids, proteins and other macromolecules (33). Controlling their cellular levels is essential for proper function. Nanomolar amounts of ROS are able to act as potent mitogens, regulating cell growth and angiogenesis. High levels of ROS may be harmful, causing damage and driving signaling pathways involved in proliferation arrest, or even in cell death (34). Several studies have implicated an increase of ROS in carcinogenesis due to a loss of proper redox control (35–39). Aberrant ROS levels are able to drive cancer initiation and progression. In general, the activity of ROS on carcinogenesis depends on their mutagenic potential. Their contribution to cancer progression and metastases is mainly due to their ability to affecting anchorage-independent cell growth (40,41), the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) (42), de novo angiogenesis (43,44) and apoptosis through the modulation of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3-kinase)/Akt pathway (41).

Moreover, the tendency of cancer cells to undergo profound changes in their own intrinsic metabolism (Warburg metabolic reprogramming), characterized by increased activity in aerobic glycolysis and by lipid metabolism deregulation, is also largely modulated by oxidative stress. Therefore, ROS may promote numerous aspects of tumor onset and progression towards a malignant phenotype (45–47). Nevertheless, it should not be overlook that high levels of ROS can be lethal for the cancer cells. This could be one of the reasons why cancer cells, in order to defend themselves, potentiate their antioxidant capacity (48,49).

4. PRDXs in tumorigenesis

Cells are endowed with several overlapping peroxide-degrading systems, the relative importance of which is a matter of debate. PRDXs are a fascinating group of thiol-dependent peroxidases that, under physiological conditions, are responsible for divergent functions, such as protecting cells against oxidative DNA damage and genomic instability, regulating cell signaling associated with H2O2, and influencing cell differentiation and proliferation, immune responses and apoptosis (50) (Fig. 6). A number of studies have demonstrated that cancer cells exhibit an increased production of ROS, in part caused by a loss in proper redox control (35,36–39). Therefore, over the course of the last few years, much attention has been paid to exploring the role of PRDXs in cancerogenesis. Increased or decreased levels of PRDXs have been demonstrated in many human cancers. Studies performed in vitro or in vivo models have demonstrated that overexpression of PRDXs may either inhibit cancer development or promote cancer growth (48), depending on the specific PRDX family member and on the cancer context.

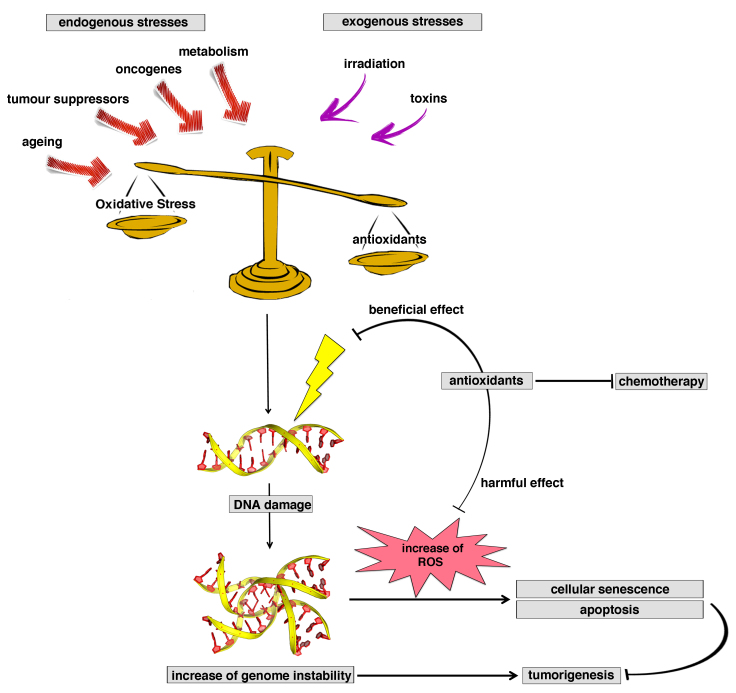

Figure 6.

Antioxidants: a ‘double-edged sword’ in tumorigenesis. Antioxidants are a double-edged sword in tumorigenesis, and may be involved in reduction of the levels or reactive oxygen species (beneficial effect) or in accelerating tumor formation, inhibiting senescence or apoptotic processes (harmful effects).

In the following chapters, the most recent findings regarding the dual action of PRDXs in tumorigenesis are reviewed and discussed. Table II summarizes different types of cancer in which the expression of an individual member of the PRDX family is altered.

Table II.

Differential expression of PRDX family members in tumor types.a

| PRDX family member | Expression levels in different tumor types | Refs. |

|---|---|---|

| PRDX1 | Increased in: Lung cancer, bladder cancer, ovarian carcinoma, aggressive esophageal squamous carcinomas, mesothelioma, glioblastoma, hilar cholangiocarcinoma, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, liver cancer and pancreatic cancer | (60–67,142) |

| Decreased in: Thyroid tumors (PTCs) | (74,75) | |

| PRDX2 | Increased in: Colorectal cancers, B cell-derived primary lymphoma cells, vaginal carcinoma, cervical cancer, ovarian cancer, prostate cancer, esophageal cancer and B-cell-derived primary lymphoma cells | (87–92,94) |

| Decreased in: Melanoma | (85) | |

| PRDX3 | Increased in: Hepatocellular carcinomas, malignant mesothelioma, breast carcinoma, prostate cancer, cervical carcinoma and lung cancer | (67,102–106) |

| PRDX4 | Increased in: Pancreatic cancer, prostate cancer, oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma, colorectal cancer, breast cancer, ovarian cancer and lung cancer | (70,90,114,116–119) |

| Decreased in: Pancreatic cancer and acute promyelocytic leukemia | (113,121) | |

| PRDX5 | Increased in: Aggressive Hodgkin lymphomas, malignant mesothelioma, breast carcinoma, ovarian carcinoma and thyroid cancer | (67,87,103,127,128) |

| Decreased in: Adrenocortical carcinoma | (129) | |

| PRDX6 | Increased in: Breast cancer, malignant mesothelioma, bladder cancer, esophageal cancer, lung cancer, ovarian cancer, pancreatic cancer, cancer of the gingivo-buccal area and lymphoma | (61,67,87,141–146) |

| Decreased in: Thyroid tumors | (75,149) |

A summary is provided of the different types of cancer in which the expression of individual members of the PRDX family is up or downregulated. PRDX, peroxiredoxin; PTCs, papillary thyroid carcinomas.

PRDX1: Dual effect in cancerogenesis

Amongst the PRDX family members, PRDX1 possess the widest cellular distribution and show the highest abundance in various tissues (51). Its cellular expression is controlled at the transcriptional level by nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-related factor 2 (NRF2) (52), and at the post-transcriptional level, through degradation and deadenylation/polyadenylation processes (53).

PRDX1 as a tumor suppressor

A tumor suppressor function of PRDX1 was first demonstrated in a knockout-mouse model, where its deficiency generated mice suffering from hemolytic anemia and multiple tumors, including mammary carcinomas (54–56). These studies suggested that the tumor suppressive effects of PRDX1 were mediated by a reduction of c-Myc transcriptional activity (55) or of phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN/AKT) activity (56). In particular, PRDX1 exerts its protective effect by oxidation of the Cys residue located within the active site of PTEN phosphatase, thereby reducing the predisposition of PRDX1-deficient mice to develop Ras-induced mammary tumors (56).

In breast cancer (estrogen-receptor-positive cases), PRDX1 prevents oxidative stress-mediated estrogen receptor α reduction. Its overexpression in these cancer tissues may be considered as a biomarker of favorable prognosis (57). In lung cancer, the tumor suppressant effect is mediated by the modulation of the ROS-mediated activation of the K-Ras/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) pathway (58). Similarly, in human acute myeloid leukemia (AML), PRDX1 promotes the reactivation of the protein tyrosine phosphatase DEP-1, a tumor suppressor that counteracts the action of the transforming kinase, FLT3 ITD (59).

PRDX1 as a tumor promoter

The tumor-promoting function of PRDX1 has been demonstrated in numerous types of human cancer, and appears to be mediated through its interaction with several cancer-associated signal pathways. An increased level of PRDX1 has been described in lung cancer (60), in bladder cancer (61), in ovarian carcinoma (62), in aggressive esophageal squamous carcinomas (63), in hilar cholangiocarcinoma (64), in liver cancer (65), in pancreatic cancer (66), in mesothelioma (67) and in glioblastoma (68). In prostate cancer, PRDX1 overexpression induces tumor growth and tumor progression through the Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-dependent regulation of tumor vasculature, increasing the expression of the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) (69). In certain lung cancer cellular models, it has become well established that the pro-oncogenic role of PRDX1 is mediated by the activation of c-Jun and AP-1 (70), and that the transforming growth factor β1 (TGFβ1)-induced EMT is caused by direct inhibition of E-cadherin expression (71). In addition, PRDX1 may exerts its tumor-promoting function by affecting intracellular signaling pathways that affect apoptosis. In thyroid cancer cells, it inhibits apoptosis through the inhibition of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1) activity (72), whereas in human hepatoma it suppresses the redox-dependent activation of caspases, inducing tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα)-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) resistance (73).

Decreased PRDX1 levels in papillary thyroid carcinomas (PTCs) (74) correlate with the presence of the BRAF V600E mutation and of lymph node metastasis, suggesting that PRDX1 reduction may be caused by mutated BRAF, and this is associated with a more aggressive clinical outcome of PTCs (75).

PRDX2: Dual effect in cancerogenesis

PRDX2 is another member of the typical 2-Cys subgroup, and it is mainly present in the cytosol (76). In red blood cells (RBCs), the oxidation-reduction cycle of PRDX2 correlates with a robust temperature-entrainable and temperature-compensated circadian rhythm, the oscillations of which result in circadian rhythm-dependent oligomerization of PRDX2 (77). Notably, the fluctuations in levels of hyperoxidized PRDX2 are not affected at the transcriptional level, considering the absence of a nucleus in the RBCs (77); neither are they controlled by sulfiredoxin (Srx), but are rather controlled by hemoglobin autoxidation and the 20S proteasome (78). Circadian rhythms are highly conserved time-tracking systems regulating important biological processes at the systemic and the cellular level (76). Interestingly, it has been recently demonstrated that the nuclear levels of PRDX2 oscillate rhythmically over two entire 24-h long cycles in HaCaT keratinocytes, contributing to the regulation of the redox balance of human keratinocytes. These findings open new perspectives for an understanding of circadian-pathophysiological processes in the skin (79). It is not yet clear whether the PRDXs are essential for circadian rhythmicity, although it is evident that their deletion has generally deleterious cellular consequences (77).

PRDX2 is one of the most efficient intracellular H2O2 scavengers compared with the other antioxidants (80). Depending on its oxidized or hyperoxidized status, PRDX2 forms homodimers or oligomers, functioning as an H2O2 scavenger or as a chaperone, respectively (81). Its expression is regulated by ROS induction in a PTEN-dependent manner (82), and at the transcriptional level by Hand1/Hand2 factor (83) or by the extensive methylation of CpG islands in the promoter region (84).

PRDX2 as a tumor suppressor

Depending on the tumor type and the stage of tumor progression, PRDX2 may exhibit strong tumor-suppressive or tumor-promoting functions. A decreased expression of PRDX2 has been demonstrated in only a few types of cancer, among which are the melanomas. The function of PRDX2 in melanoma cell growth and metastasis has not yet been fully elucidated. To date, it has been demonstrated, both in vitro in melanoma cell lines and in vivo in metastatic melanoma models, that a downregulation of PRDX2 correlates with increased proliferative and migratory activities, and with the acquisition of a metastatic potential. In particular, it appears that the PRX2-mediated signaling pathway for suppression of melanoma metastasis involves a synergistic collaboration of the processes of ERK-dependent E-cadherin expression and the Src-dependent retention of β-catenin in the adherens junctions (85). In a colorectal cancer (CRC) cellular model, PRDX2 inhibits TGFβ1-induced EMT, reducing the invasive phenotype through the modulation of the transcription factors, Twist1, Snail, ZEB1 and ZEB2 (86).

PRDX2 as a tumor promoter

Over the course of the last few years, a number of studies, instead, have revealed that PRDX2 is increased in various human malignancies, suggesting a possible role for PRDX2 as a tumor promoter. High levels of PRDX2 and 4 were observed in ovarian borderline cancer compared with the other benign ovarian lesions, allowing a hypothesis to be made for the potential use of these in determining a differential diagnosis between benign and borderline epithelial ovarian tumors (87). Elevated expression levels of PRDX2 have also been found in vaginal carcinoma (88), in cervical cancer (89), in prostate cancer (90), in esophageal cancer (91) and, more recently, in B cell-derived primary lymphoma cells (92). In breast cancer, PRDX2 works like a ‘metabolic adaptor’ driver protein that specifically induces the selective growth of metastatic cells in the lung by protecting them against oxidative stress (93). The dual action of PRDX2 in tumorigenesis has been demonstrated in a CRC model. Lu et al (94), in contrast with what was reported by Feng et al (86), demonstrated that PRDX2 overexpression in CRC tissues was strongly correlated with a more aggressive cancer behavior, tumor metastasis and the tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) stage, indicating a possible role for PRDX2 in CRC progression. Taken together, these data suggest that the mechanism by which PRDX2 exerts its oncogenic action is still poorly understood, and further studies are required.

PRDX3: Tumor-promoting effects

PRDX3 is a mitochondrial member of the antioxidant family of thioredoxin peroxidases that uses mitochondrial thioredoxin 2 (Trx2) as a source of reducing equivalents to scavenge hydrogen peroxide (95). Its specific localization to the mitochondria suggests that PRDX3, together with its mitochondrion-specific electron suppliers, Trx2 and Trx reductase 2 (TrxR2), may provide a primary line of defense against H2O2 produced by the mitochondrial respiratory chain (96). PRDX3 is highly sensitive to the oxidative state. The regulation of its expression involves sirtuin 1 (SIRT1), a class III histone deacetylase that is not cell-type-specific, in bovine aortic endothelial cells. SIRT1 positively controls PRDX3 expression by an enhancement of the formation of the PGC-1α/FoxO3a transcriptional complex (97). Depending on the cancer type, the regulation of PRDX3 expression may be mediated by different factors. In colon cancer stem cells (CSCs), the forkhead box protein 1, FOXM1, activates transcription of PRDX3 and the expression of CD133 (98). In medulloblastoma tumor tissue samples and cell lines, the level of the microRNA, miR-383, is a modulator of PRDX3 expression (99), whereas in human prostate cancer cells, miR-23b directly regulates PRDX3 expression under normal and hypoxic conditions (100). Finally, in von Hippel-Lindau (VHL)-deficient clear cell renal cell carcinoma (CCRCC), the transcription factor, hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1), downregulates the level of PRDX3 (101).

A high level of PRDX3 expression has been reported in hepatocellular carcinomas (102), in malignant mesothelioma (67), in breast carcinoma (103), in prostate cancer (104), in lung cancer (105) and in cervical carcinoma (106). All these studies have demonstrated that PRDX3 overexpression in cancer cells correlates with a more aggressive phenotype.

PRDX4: Tumor-promoting effects

PRDX4 is another member of the typical 2-Cys PRDX family, homologous with other typical 2-Cys PRDXs, such as PRDX1 and PRDX2, which share the same catalytic mechanism. It is located predominantly in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and extracellular spaces, with the highest expression occurring in the pancreas, liver and heart, and lowest expression in blood leukocytes and the brain (107). A distinctive hydrophobic amino-terminus in PRDX4 functions as a signal sequence involved in the process of secretion from the cells (108). No solid evidence is available regarding the role of extracellular PRDX4 as a biomarker in certain types of disease (24). It has been suggested that the secretable form of PRDX4 may be involved in the interactions between carcinoma cells and the extracellular environment (109).

PRDX4 controls oxidative stress by reducing H2O2 to water in a thiol-dependent catalytic cycle. In addition, it has an important chaperone function, operating by means of a versatile mechanism that allows it to switch from redox-dependent and reversibly convertible, disulfide-linked homodimers to higher-order multimers, which enables the interaction with binding partners, including stress-responsive kinases, membrane proteins and immune modulators (110). As a chaperone protein, it cooperates with the protein disulfide isomerase (PDI), a key foldase and chaperone at the ER level, mediating the oxidative folding of various ER proteins (111). The PRDX4/PDI system was established to be a new oxidative folding pathway, working in parallel with the ER oxidoreductin 1 (ERO1)/PDI pathway (24).

As described above for the other PRDXs, modifications in PRDX4 levels have been associated with invasion, recurrence, prognosis, and other characteristics of cancer (112).

In pancreatic cancer, several reports have described the downregulation or upregulation of PRDX4 (113,114), although it is not yet clear whether the PRDX4 expression level may be considered to be a cause or an effect of pancreatic cancer. PRDX4 is overexpressed in prostate cancer (90), where it enhances the rate of cell proliferation (115). In other types of epithelial cancers, such as oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma (116), breast cancer (117), ovarian cancer (118), CRC (119) or lung cancer (70), overexpression of PRDX4 correlates with the metastatic potential. In particular, in lung cancer A549 cells, the Srx-PRDX4 complex significantly contributes to the maintenance of anchorage-independent colony formation, cell migration and invasion (120). It is noteworthy that PRDX4 is overexpressed in the majority of cancers where Srx is also overexpressed (113), contributing to cell proliferation by the activation of the RAS-RAF-MEK signaling pathway (120). On the other hand, its marked downregulation has been reported in acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) (121).

PRDX5: Tumor-promoting effects

PRDX5 was the last member to be identified among the six mammalian PRDXs. It is the unique atypical 2-Cys PRDX in mammals, widely expressed in tissues at different levels, with a large subcellular distribution including the mitochondria, the peroxisomes, the cytosol and the nucleus (22). PRDX5 is a thioredoxin peroxidase that acts mainly by reducing alkyl hydroperoxides and peroxynitrite via cytosolic or mitochondrial thioredoxins. Its crystal structures highlight the unconventional enzymatic mechanism, involving two catalytic Cys residues that provide an opportunity for reaction with an additional molecule of H2O2, leading to overoxidation of Cp (122). PRDX5 is a cytoprotective antioxidant enzyme rather than a redox sensor, able to act against endogenous or exogenous peroxide attacks. Its overexpression in different subcellular compartments defends cells against death provoked by nitro-oxidative stresses, while its silencing makes the cells more susceptible to oxidative damage and apoptosis (122). It is constitutively expressed at a high level in different mammalian cell lines and normal tissues, but the specific transcription factors involved in the regulation of its expression have not yet been completely identified. It is known that transcription factors such as AP-1, nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB), antioxidant response element (ARE), insulin response element (InRE), glucocorticoid response element (GRE) (123), and also c-Myc (124), may directly modulate PRDX5 expression by interacting with putative responsive elements in the 5′-flanking region of the gene. Other transcription factors, such as nuclear respiratory factor 1 (NRF-1) and nuclear respiratory factor 2 (NRF-2; GABPA), involved in the response of mammalian cells to oxidative stress and in the biogenesis of mitochondria, are also able to modulate PRDX5 expression in an indirect way (123,125). c-Myc not only directly controls PRDX5 transcription, but also contributes in the maintenance of ROS homeostasis through its ability to selectively induce the transcription of specific PRDXs when the function of one of them is compromised (124). Up- or downregulation of PRDX5 has been reported in different types of cancer. An upregulation of transcriptional activity of PRDX5, mediated by E-twenty-six transcription factor 1 and 2 (Ets1/2) and high-mobility-group protein B1 (HMGB1), has been described in human prostate and epidermoid cancer cells exposed to H2O2 or hypoxia (126). Increased levels of PRDX5 have been reported in aggressive Hodgkin's lymphomas (127), in malignant mesothelioma (67), in breast carcinoma (103), in ovarian carcinoma (87) and in thyroid cancer (128). Reduced levels of PRDX5 expression have been described only in adrenocortical carcinoma (129).

PRDX6: Tumor-promoting effects

PRDX6 is the prototype and the only mammalian 1-Cys member of the PRDX family. Homologous 1-Cys proteins are widely distributed throughout all kingdoms, and they have been described in archaea, bacteria, parasites, yeast, insects, mollusks, amphibians, birds and other orders (130) (Table I). Although PRDX6 shares structural and functional properties with other members of the family, it has important and unique characteristics: It has a single conserved Cys residue causing a different catalytic cycle, and it uses glutathione (GSH) instead of thioredoxin as the physiological reductant. Furthermore, PRDX6 is able to bind and reduce phospholipid hydroperoxides, serving an important role in the repair of membrane damage caused by oxidative stress and, finally, it is a bifunctional enzyme with both phospholipase A2 (PLA2) activity and peroxidase function (130). Its catalytic Cys residue is buried at the base of a narrow pocket, differently from the other PRDXs, which renders PRDX6 unable to dimerize through disulfide formation in the native configuration, although it can homodimerize and multimerize through hydrophobic interactions (131).

PRDX6 has a widespread distribution in all organs, and essentially in all cell types (130). Its expression is regulated by the mainly redox-active regulators, such as Nrf2, Nrf3 (132,133), NF-κB (134), Sp1 (135), c-Jun, c-Myc (130) and HSF1 (136), which are able to interact with the ARE and the putative GRE localized in the PRDX6 gene promoter region. PRDX6 has been reported to be implicated in the development and progression of several human diseases, such as Alzheimer's disease (137), Parkinson's dementia (138), diabetes (139), cataractogenesis (140) and cancer. Concerning the neoplastic diseases, elevated levels of PRDX6 have been described in breast cancer (141), in malignant mesothelioma (67), in bladder cancer (61), in esophageal cancer (142), in lung (143), ovarian (87) and pancreas (144) cancer, in cancer of the gingivo-buccal area (145), and in lymphoma (146). Elevated expression levels of PRDX6 have been associated with a more invasive phenotype and metastatic potential of breast cancer (147), and with a worse prognosis of clinically localized prostate cancer following radical prostatectomy (148).

By contrast, studies performed using a thyroid proteomic approach have highlighted the reduction of PRDX6 in follicular adenomas (149), suggesting a possible role for this protein as a complementary marker to distinguish between different follicular neoplasms. More recently, a marked reduction in PRDX6 levels has been demonstrated in a cohort of PTCs (75). Taken together, all these studies have demonstrated that PRDX6 has a pro-tumorigenic function, promoting cell proliferation by its peroxidase activity, and facilitating invasiveness by means of its PLA2 activity (150).

To date, the association between PRDX6 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and cancer has yet to be fully elucidated. In esophageal cancer, no association was identified between the risk of cancer and clinicopathological characteristics, including the tumor grade and stage, and the presence of SNPs (91). However, preliminary studies in breast cancer have demonstrated that the survival of carriers of the PRDX6 SNPs, rs4916362 and rs7314, was consistently less favorable (151).

5. PRDXs and chemoresistance

Cancer cells, compared with normal cells, have a high rate of ROS production as by-products of their metabolism (152), and to survive with this redox status, the levels of antioxidant proteins, such as CAT, SOD, glutaredoxin and PRDXs, are increased (152–154). This unique capability of cancer cells may serve an important role also in the development of resistance to chemo- or radiotherapy, as these treatments are strongly dependent on ROS-induced cytotoxicity. A search of the literature demonstrates that increased levels of PRDXs are often associated with radioresistance or chemoresistance to numerous drugs. High levels of PRDX2 correlate with radioresistance in breast cancer and glioma cells (155), as well as with cisplatin chemoresistance in gastric cancer cell lines (156) and in human erythroleukemia K652 and human ovarian carcinoma SKOV-3 cells (157), since increased levels of this antioxidant inhibit apoptosis. Furthermore, in head-and-neck cancer and in gastric carcinoma cells, PRDX2-specific antisense vectors restore the induction of pro-apoptotic pathways following radiation or cisplatin treatment, confirming the important role of PRDX2 in the resistance process (158). Several other types of cancer, including erythroleukemia, breast carcinoma and human ovarian carcinoma, develop cisplatin resistance through a significant increase in the levels of PRDX1, PRDX3 and PRDX6 (157,159). In addition, the upregulation of PRDX2 is also involved in the development of gefitinib resistance in a non-small cell lung carcinoma model, where it is responsible for the induction of tumor cell growth via activation of phosphorylated c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and the suppression of apoptosis signaling (160). In breast cancer cell lines, increased PRDX3 levels correlate with resistance to the chemotherapeutic drug, doxorubicin (161). PRDX3 controls the apoptotic signaling pathway through the regulation of cytochrome c release from the mitochondria, as well as through interaction with the complex of leucine zipper-bearing kinase (LZK) and IKB kinase (IKK). Therefore, it is conceivable that drugs targeting PRDX3 and the mitochondrion-specific electron suppliers, Trx2, TrxR2 and Srx, could represent a good strategy for improving the response to various chemotherapeutic agents, including cisplatin, paclitaxel and etoposide (162,163). Finally, there is evidence that PRDX5 is also involved in the chemoresistance to adriamycin, bleomycin, vinblastine and dacarbazine in patients affected with aggressive Hodgkin's lymphomas (127) and in vitro in the lung carcinoma U1810 cell line (164), always by inhibiting chemotherapeutic-induced apoptosis.

Chemoresistance is a complex phenomenon caused by multiple and heterogeneous mechanisms of action, which are orchestrated not only by the tumor microenvironment, but also by the biology of the tumor itself. The modulation of endogenous antioxidant levels may be a determining factor for the sensitivity of certain tumors to various chemotherapeutic agents. In addition, it is important to highlight that the regulation of intracellular antioxidant concentration is a ‘double-edged sword’: On the one hand, enhanced antioxidant activity represents an advantageous protection of the cells from ROS, whereas, on the other hand, the depletion of antioxidants represents an important strategy to sensitize cancer cells to chemotherapy (chemosensitization) (50).

6. Conclusions

PRDXs serve a critical role in several physiological, as well as pathological, conditions involving redox signaling. Although their protective role in cardiovascular and neurological diseases is clear, their role in cancer remains controversial: Different PRDX isoforms may have a tumor-suppressor or an oncogenic role, depending on the cancer type. Considering the peroxidase-dependent and -independent secondary functions and the fine balance involved in the regulation of the oligomeric state and the function of the PRDX, more has been learnt about these antioxidants and their involvement in the control of cell growth and survival, particularly as a part of normal growth and development. To date, it remains to be clarified how the levels of peroxide and the peroxidases interplay, and how the regulatory behavior may change depending on the different developmental stages of the tissue, or on the disease states. Several studies have hypothesized that the ROS resistance of the cancer cells is sustained, at least in part, by overexpression of the PRDXs responsible for the antioxidant activity increase and/or the alteration in growth and activation of the death pathways (112,165). On the other hand, in certain cases PRDXs have been suggested to function as tumor preventers, rather than as tumor suppressors (166), in that, via detoxification of the ROS, they contribute to the maintenance of genomic integrity. In conclusion, in the future it will be crucial to clarify the exact role of PRDXs in cellular homeostasis, as well as in cancer development and drug resistance, in order to develop new target therapeutic strategies for cancer treatment or prevention.

References

- 1.Valko M, Leibfritz D, Moncol J, Cronin MT, Mazur M, Telser J. Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39:44–84. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duracková Z. Some current insights into oxidative stress. Physiol Res. 2010;59:459–469. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.931844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xing M. Oxidative stress: A new risk factor for thyroid cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2012;19:C7–C11. doi: 10.1530/ERC-11-0360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dröge W. Free radicals in the physiological control of cell function. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:47–95. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00018.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giorgio M, Trinei M, Migliaccio E, Pelicci PG. Hydrogen peroxide: A metabolic by-product or a common mediator of ageing signals? Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:722–728. doi: 10.1038/nrm2240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rhee SG, Bae YS, Lee SR, Kwon J. Hydrogen peroxide: A key messenger that modulates protein phosphorylation through cysteine oxidation. Sci STKE. 2000;2000:pe1. doi: 10.1126/stke.2000.53.pe1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cha MK, Kim HK, Kim IH. Thioredoxin-linked ‘thiol peroxidase’ from periplasmic space of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:28635–28641. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.48.28635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou Y, Wan XY, Wang HL, Yan ZY, Hou YD, Jin DY. Bacterial scavengase p20 is structurally and functionally related to peroxiredoxins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;233:848–852. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nogoceke E, Gommel DU, Kiess M, Kalisz HM, Flohé L. A Unique cascade of oxidoreductases catalyses trypanothione-mediated peroxide metabolism in Crithidia fasciculata. Biol Chem. 1997;378:827–836. doi: 10.1515/bchm.1997.378.8.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bryk R, Griffin P, Nathan C. Peroxynitrite reductase activity of bacterial peroxiredoxins. Nature. 2000;407:211–215. doi: 10.1038/35025109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hillas PJ, del Alba FS, Oyarzabal J, Wilks A, De Montellano PR Ortiz. The AhpC and AhpD antioxidant defense system of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:18801–18809. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001001200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karplus PA. A primer on peroxiredoxin biochemistry. Free Radic Biol Med. 2015;80:183–190. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Winterbourn CC. Reconciling the chemistry and biology of reactive oxygen species. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4:278–286. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim K, Kim IH, Lee KY, Rhee SG, Stadtman ER. The isolation and purification of a specific ‘protector’ protein which inhibits enzyme inactivation by a thiol/Fe(III)/O2 mixed-function oxidation system. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:4704–4711. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chae HZ, Robison K, Poole LB, Church G, Storz G, Rhee SG. Cloning and sequencing of thiol-specific antioxidant from mammalian brain: Alkyl hydroperoxide reductase and thiol-specific antioxidant define a large family of antioxidant enzymes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:7017–7021. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.7017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edgar RS, Green EW, Zhao Y, van Ooijen G, Olmedo M, Qin X, Xu Y, Pan M, Valekunja UK, Feeney KA, et al. Peroxiredoxins are conserved markers of circadian rhythms. Nature. 2012;485:459–464. doi: 10.1038/nature11088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nelson KJ, Knutson ST, Soito L, Klomsiri C, Poole LB, Fetrow JS. Analysis of the peroxiredoxin family: Using active-site structure and sequence information for global classification and residue analysis. Proteins. 2011;79:947–964. doi: 10.1002/prot.22936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perkins A, Gretes MC, Nelson KJ, Poole LB, Karplus PA. Mapping the active site helix-to-strand conversion of CxxxxC peroxiredoxin Q enzymes. Biochemistry. 2012;51:7638–7650. doi: 10.1021/bi301017s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hall A, Nelson K, Poole LB, Karplus PA. Structure-based insights into the catalytic power and conformational dexterity of peroxiredoxins. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;15:795–815. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dammeyer P, Arnér ES. Human protein atlas of redox systems-what can be learnt? Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1810:111–138. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rhee SG, Chae HZ, Kim K. Peroxiredoxins: A historical overview and speculative preview of novel mechanisms and emerging concepts in cell signaling. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;38:1543–1552. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seo MS, Kang SW, Kim K, Baines IC, Lee TH, Rhee SG. Identification of a new type of mammalian peroxiredoxin that forms an intramolecular disulfide as a reaction intermediate. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:20346–20354. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001943200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kang SW, Baines IC, Rhee SG. Characterization of a mammalian peroxiredoxin that contains one conserved cysteine. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:6303–6311. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.11.6303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fujii J, Ikeda Y, Kurahashi T, Homma T. Physiological and pathological views of peroxiredoxin 4. Free Radic Biol Med. 2015;83:373–379. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rhee SG, Kang SW, Chang TS, Jeong W, Kim K. Peroxiredoxin, a novel family of peroxidases. IUBMB Life. 2001;52:35–41. doi: 10.1080/15216540252774748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hofmann B, Hecht HJ, Flohé L. Peroxiredoxins. Biol Chem. 2002;383:347–364. doi: 10.1515/BC.2002.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Declercq JP, Evrard C, Clippe A, Stricht DV, Bernard A, Knoops B. Crystal structure of human peroxiredoxin 5, a novel type of mammalian peroxiredoxin at 1.5 A resolution. J Mol Biol. 2001;311:751–759. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Monteiro G, Horta BB, Pimenta DC, Augusto O, Netto LE. Reduction of 1-Cys peroxiredoxins by ascorbate changes the thiol-specific antioxidant paradigm, revealing another function of vitamin C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:4886–4891. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700481104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karplus PA, Hall A. Structural survey of the peroxiredoxins. Subcell Biochem. 2007;44:41–60. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4020-6051-9_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wood ZA, Poole LB, Hantgan RR, Karplus PA. Dimers to Doughnuts: Redox-sensitive oligomerization of 2-cysteine peroxiredoxins. Biochemistry. 2002;41:5493–5504. doi: 10.1021/bi012173m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barranco-Medina S, Lázaro JJ, Dietz KJ. The oligomeric conformation of peroxiredoxins links redox state to function. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:1809–1816. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fujii J, Ikeda Y. Advances in our understanding of peroxiredoxin, a multifunctional, mammalian redox protein. Redox Rep. 2002;7:123–130. doi: 10.1179/135100002125000352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pisoschi AM, Pop A. The role of antioxidants in the chemistry of oxidative stress: A review. Eur J Med Chem. 2015;97:55–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fulda S, Gorman AM, Hori O, Samali A. Cellular stress responses: Cell survival and cell death. Int J Cell Biol. 2010;2010:214074. doi: 10.1155/2010/214074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kamiguti AS, Serrander L, Lin K, Harris RJ, Cawley JC, Allsup DJ, Slupsky JR, Krause KH, Zuzel M. Expression and activity of NOX5 in the circulating malignant B cells of hairy cell leukemia. J Immunol. 2005;175:8424–8430. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.12.8424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsao SM, Yin MC, Liu WH. Oxidant stress and B vitamins status in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Nutr Cancer. 2007;59:8–13. doi: 10.1080/01635580701365043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Khandrika L, Kumar B, Koul S, Maroni P, Koul HK. Oxidative stress in prostate cancer. Cancer Lett. 2009;282:125–136. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Patel BP, Rawal UM, Dave TK, Rawal RM, Shukla SN, Shah PM, Patel PS. Lipid peroxidation, total antioxidant status, and total thiol levels predict overall survival in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma. Integr Cancer Ther. 2007;6:365–372. doi: 10.1177/1534735407309760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Szatrowski TP, Nathan CF. Production of large amounts of hydrogen peroxide by human tumor cells. Cancer Res. 1991;51:794–798. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nishikawa M. Reactive oxygen species in tumor metastasis. Cancer Lett. 2008;266:53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Clerkin JS, Naughton R, Quiney C, Cotter TG. Mechanisms of ROS modulated cell survival during carcinogenesis. Cancer Lett. 2008;266:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Krstić J, Trivanović D, Mojsilović S, Santibanez JF. Transforming Growth Factor-Beta and Oxidative Stress Interplay: Implications in Tumorigenesis and cancer progression. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2015;2015:654594. doi: 10.1155/2015/654594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ushio-Fukai M, Nakamura Y. Reactive oxygen species and angiogenesis: NADPH oxidase as target for cancer therapy. Cancer Lett. 2008;266:37–52. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.02.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fiaschi T, Chiarugi P. Oxidative stress, tumor microenvironment, and metabolic reprogramming: A diabolic liaison. Int J Cell Biol. 2012;2012:762825. doi: 10.1155/2012/762825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weinberg F, Chandel NS. Reactive oxygen species-dependent signaling regulates cancer. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:3663–3673. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-0099-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cairns RA, Harris IS, Mak TW. Regulation of cancer cell metabolism. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:85–95. doi: 10.1038/nrc2981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Park MH, Jo M, Kim YR, Lee CK, Hong JT. Roles of peroxiredoxins in cancer, neurodegenerative diseases and inflammatory diseases. Pharmacol Ther. 2016;163:1–23. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2016.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Taguchi K, Motohashi H, Yamamoto M. Molecular mechanisms of the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway in stress response and cancer evolution. Genes Cells. 2011;16:123–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2010.01473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kwee JK. A paradoxical chemoresistance and tumor suppressive role of antioxidant in solid cancer cells: A strange case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:209845. doi: 10.1155/2014/209845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Neumann CA, Cao J, Manevich Y. Peroxiredoxin 1 and its role in cell signaling. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:4072–4078. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.24.10242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim YJ, Ahn JY, Liang P, Ip C, Zhang Y, Park YM. Human prx1 gene is a target of Nrf2 and is up-regulated by hypoxia/reoxygenation: Implication to tumor biology. Cancer Res. 2007;67:546–554. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thélie A, Papillier P, Pennetier S, Perreau C, Traverso JM, Uzbekova S, Mermillod P, Joly C, Humblot P, Dalbiès-Tran R. Differential regulation of abundance and deadenylation of maternal transcripts during bovine oocyte maturation in vitro and in vivo. BMC Dev Biol. 2007;7:125. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-7-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Neumann CA, Krause DS, Carman CV, Das S, Dubey DP, Abraham JL, Bronson RT, Fujiwara Y, Orkin SH, Van Etten RA. Essential role for the peroxiredoxin Prdx1 in erythrocyte antioxidant defence and tumour suppression. Nature. 2003;424:561–565. doi: 10.1038/nature01819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Egler RA, Fernandes E, Rothermund K, Sereika S, de Souza-Pinto N, Jaruga P, Dizdaroglu M, Prochownik EV. Regulation of reactive oxygen species, DNA damage, and c-Myc function by peroxiredoxin 1. Oncogene. 2005;24:8038–8050. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cao J, Schulte J, Knight A, Leslie NR, Zagozdzon A, Bronson R, Manevich Y, Beeson C, Neumann CA. Prdx1 inhibits tumorigenesis via regulating PTEN/AKT activity. EMBO J. 2009;28:1505–1517. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.O'Leary PC, Terrile M, Bajor M, Gaj P, Hennessy BT, Mills GB, Zagozdzon A, O'Connor DP, Brennan DJ, Connor K, et al. Peroxiredoxin-1 protects estrogen receptor α from oxidative stress-induced suppression and is a protein biomarker of favorable prognosis in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2014;16:R79. doi: 10.1186/bcr3691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Park YH, Kim SU, Lee BK, Kim HS, Song IS, Shin HJ, Han YH, Chang KT, Kim JM, Lee DS, et al. Prx I suppresses K-ras-driven lung tumorigenesis by opposing redox-sensitive ERK/cyclin D1 pathway. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;19:482–496. doi: 10.1089/ars.2011.4421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Godfrey R, Arora D, Bauer R, Stopp S, Müller JP, Heinrich T, Böhmer SA, Dagnell M, Schnetzke U, Scholl S, et al. Cell transformation by FLT3 ITD in acute myeloid leukemia involves oxidative inactivation of the tumor suppressor protein-tyrosine phosphatase DEP-1/PTPRJ. Blood. 2012;119:4499–4511. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-336446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim JH, Bogner PN, Baek SH, Ramnath N, Liang P, Kim HR, Andrews C, Park YM. Up-regulation of peroxiredoxin 1 in lung cancer and its implication as a prognostic and therapeutic target. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:2326–2333. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Quan C, Cha EJ, Lee HL, Han KH, Lee KM, Kim WJ. Enhanced expression of peroxiredoxin I and VI correlates with development, recurrence and progression of human bladder cancer. J Urol. 2006;175:1512–1516. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00659-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chung KH, Lee DH, Kim Y, Kim TH, Huh JH, Chung SG, Lee S, Lee C, Ko JJ, An HJ. Proteomic identification of overexpressed PRDX 1 and its clinical implications in ovarian carcinoma. J Proteome Res. 2010;9:451–457. doi: 10.1021/pr900811x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ren P, Ye H, Dai L, Liu M, Liu X, Chai Y, Shao Q, Li Y, Lei N, Peng B, et al. Peroxiredoxin 1 is a tumor-associated antigen in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2013;30:2297–2303. doi: 10.3892/or.2013.2714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhou J, Shen W, He X, Qian J, Liu S, Yu G. Overexpression of Prdx1 in hilar cholangiocarcinoma: A predictor for recurrence and prognosis. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:9863–9874. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sun YL, Cai JQ, Liu F, Bi XY, Zhou LP, Zhao XH. Aberrant expression of peroxiredoxin 1 and its clinical implications in liver cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:10840–10852. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i38.10840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cai CY, Zhai LL, Wu Y, Tang ZG. Expression and clinical value of peroxiredoxin-1 in patients with pancreatic cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41:228–235. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2014.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kinnula VL, Lehtonen S, Sormunen R, Kaarteenaho-Wiik R, Kang SW, Rhee SG, Soini Y. Overexpression of peroxiredoxins I, II, III, V, and VI in malignant mesothelioma. J Pathol. 2002;196:316–323. doi: 10.1002/path.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Svendsen A, Verhoeff JJ, Immervoll H, Brøgger JC, Kmiecik J, Poli A, Netland IA, Prestegarden L, Planagumà J, Torsvik A, et al. Expression of the progenitor marker NG2/CSPG4 predicts poor survival and resistance to ionising radiation in glioblastoma. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;122:495–510. doi: 10.1007/s00401-011-0867-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Riddell JR, Maier P, Sass SN, Moser MT, Foster BA, Gollnick SO. Peroxiredoxin 1 stimulates endothelial cell expression of VEGF via TLR4 dependent activation of HIF-1α. PLoS One. 2012;7:e50394. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jiang H, Wu L, Mishra M, Chawsheen HA, Wei Q. Expression of peroxiredoxin 1 and 4 promotes human lung cancer malignancy. Am J Cancer Res. 2014;4:445–460. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ha B, Kim EK, Kim JH, Lee HN, Lee KO, Lee SY, Jang HH. Human peroxiredoxin 1 modulates TGF-β1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition through its peroxidase activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;421:33–37. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.03.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Du ZX, Yan Y, Zhang HY, Liu BQ, Gao YY, Niu XF, Guan Y, Meng X, Wang HQ. Suppression of MG132-mediated cell death by peroxiredoxin 1 through influence on ASK1 activation in human thyroid cancer cells. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2010;17:553–560. doi: 10.1677/ERC-09-0269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Song IS, Kim SU, Oh NS, Kim J, Yu DY, Huang SM, Kim JM, Lee DS, Kim NS. Peroxiredoxin I contributes to TRAIL resistance through suppression of redox-sensitive caspase activation in human hepatoma cells. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:1106–1114. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yanagawa T, Ishikawa T, Ishii T, Tabuchi K, Iwasa S, Bannai S, Omura K, Suzuki H, Yoshida H. Peroxiredoxin I expression in human thyroid tumors. Cancer Lett. 1999;145:127–132. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3835(99)00243-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nicolussi A, D'Inzeo S, Mincione G, Buffone A, Di Marcantonio MC, Cotellese R, Cichella A, Capalbo C, Di Gioia C, Nardi F, et al. PRDX1 and PRDX6 are repressed in papillary thyroid carcinomas via BRAF V600E-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Int J Oncol. 2014;44:548–556. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2013.2208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wood ZA, Poole LB, Karplus PA. Peroxiredoxin evolution and the regulation of hydrogen peroxide signaling. Science. 2003;300:650–653. doi: 10.1126/science.1080405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.O'Neill JS, Reddy AB. Circadian clocks in human red blood cells. Nature. 2011;469:498–503. doi: 10.1038/nature09702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cho CS, Yoon HJ, Kim JY, Woo HA, Rhee SG. Circadian rhythm of hyperoxidized peroxiredoxin II is determined by hemoglobin autoxidation and the 20S proteasome in red blood cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:12043–12048. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1401100111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Avitabile D, Ranieri D, Nicolussi A, D'Inzeo S, Capriotti AL, Genovese L, Proietti S, Cucina A, Coppa A, Samperi R, et al. Peroxiredoxin 2 nuclear levels are regulated by circadian clock synchronization in human keratinocytes. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2014;53:24–34. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2014.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sobotta MC, Liou W, Stöcker S, Talwar D, Oehler M, Ruppert T, Scharf AN, Dick TP. Peroxiredoxin-2 and STAT3 form a redox relay for H2O2 signaling. Nat Chem Biol. 2015;11:64–70. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rhee SG, Woo HA. Multiple functions of peroxiredoxins: Peroxidases, sensors and regulators of the intracellular messenger H2O2, and protein chaperones. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;15:781–794. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Huo YY, Li G, Duan RF, Gou Q, Fu CL, Hu YC, Song BQ, Yang ZH, Wu DC, Zhou PK. PTEN deletion leads to deregulation of antioxidants and increased oxidative damage in mouse embryonic fibroblasts. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;44:1578–1591. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Barbosa AC, Funato N, Chapman S, McKee MD, Richardson JA, Olson EN, Yanagisawa H. Hand transcription factors cooperatively regulate development of the distal midline mesenchyme. Dev Biol. 2007;310:154–168. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.07.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Furuta J, Nobeyama Y, Umebayashi Y, Otsuka F, Kikuchi K, Ushijima T. Silencing of Peroxiredoxin 2 and aberrant methylation of 33 CpG islands in putative promoter regions in human malignant melanomas. Cancer Res. 2006;66:6080–6086. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lee DJ, Kang DH, Choi M, Choi YJ, Lee JY, Park JH, Park YJ, Lee KW, Kang SW. Peroxiredoxin-2 represses melanoma metastasis by increasing E-Cadherin/β-Catenin complexes in adherens junctions. Cancer Res. 2013;73:4744–4757. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Feng J, Fu Z, Guo J, Lu W, Wen K, Chen W, Wang H, Wei J, Zhang S. Overexpression of peroxiredoxin 2 inhibits TGF-β1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cell migration in colorectal cancer. Mol Med Rep. 2014;10:867–873. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.2316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Pylväs M, Puistola U, Kauppila S, Soini Y, Karihtala P. Oxidative stress-induced antioxidant enzyme expression is an early phenomenon in ovarian carcinogenesis. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:1661–1667. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hellman K, Alaiya AA, Becker S, Lomnytska M, Schedvins K, Steinberg W, Hellström AC, Andersson S, Hellman U, Auer G. Differential tissue-specific protein markers of vaginal carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:1303–1314. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kim K, Yu M, Han S, Oh I, Choi YJ, Kim S, Yoon K, Jung M, Choe W. Expression of human peroxiredoxin isoforms in response to cervical carcinogenesis. Oncol Rep. 2009;21:1391–1396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Basu A, Banerjee H, Rojas H, Martinez SR, Roy S, Jia Z, Lilly MB, De León M, Casiano CA. Differential expression of peroxiredoxins in prostate cancer: Consistent upregulation of PRDX3 and PRDX4. Prostate. 2011;71:755–765. doi: 10.1002/pros.21292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zhang B, Wang K, He G, Guan X, Liu B, Liu Y, Bai Y. Polymorphisms of peroxiredoxin 1, 2 and 6 are not associated with esophageal cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2012;138:621–626. doi: 10.1007/s00432-011-1119-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Trzeciecka A, Klossowski S, Bajor M, Zagozdzon R, Gaj P, Muchowicz A, Malinowska A, Czerwoniec A, Barankiewicz J, Domagala A, et al. Dimeric peroxiredoxins are druggable targets in human Burkitt lymphoma. Oncotarget. 2016;7:1717–1731. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Stresing V, Baltziskueta E, Rubio N, Blanco J, Arriba MC, Valls J, Janier M, Clézardin P, Sanz-Pamplona R, Nieva C, et al. Peroxiredoxin 2 specifically regulates the oxidative and metabolic stress response of human metastatic breast cancer cells in lungs. Oncogene. 2013;32:724–735. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lu W, Fu Z, Wang H, Feng J, Wei J, Guo J. Peroxiredoxin 2 is upregulated in colorectal cancer and contributes to colorectal cancer cells' survival by protecting cells from oxidative stress. Mol Cell Biochem. 2014;387:261–270. doi: 10.1007/s11010-013-1891-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Watabe S, Hiroi T, Yamamoto Y, Fujioka Y, Hasegawa H, Yago N, Takahashi SY. SP-22 is a thioredoxin-dependent peroxide reductase in mitochondria. Eur J Biochem. 1997;249:52–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.t01-1-00052.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Miranda-Vizuete A, Damdimopoulos AE, Spyrou G. The mitochondrial thioredoxin system. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2000;2:801–810. doi: 10.1089/ars.2000.2.4-801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Olmos Y, Sánchez-Gómez FJ, Wild B, García-Quintans N, Cabezudo S, Lamas S, Monsalve M. SirT1 regulation of antioxidant genes is dependent on the formation of a FoxO3a/PGC-1α complex. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;19:1507–1521. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Song IS, Jeong YJ, Jeong SH, Heo HJ, Kim HK, Bae KB, Park YH, Kim SU, Kim JM, Kim N, et al. FOXM1-Induced PRX3 regulates stemness and survival of colon cancer cells via maintenance of mitochondrial function. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:1006–1016.e9. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Li KK, Pang JC, Lau KM, Zhou L, Mao Y, Wang Y, Poon WS, Ng HK. MiR-383 is downregulated in medulloblastoma and targets peroxiredoxin 3 (PRDX3) Brain Pathol. 2013;23:413–425. doi: 10.1111/bpa.12014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.He HC, Zhu JG, Chen XB, Chen SM, Han ZD, Dai QS, Ling XH, Fu X, Lin ZY, Deng YH, et al. MicroRNA-23b downregulates peroxiredoxin III in human prostate cancer. FEBS Lett. 2012;586:2451–2458. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Xi H, Gao YH, Han DY, Li QY, Feng LJ, Zhang W, Ji G, Xiao JC, Zhang HZ, Wei Q. Hypoxia inducible factor-1α suppresses Peroxiredoxin 3 expression to promote proliferation of CCRCC cells. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:3390–3394. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Choi JH, Kim TN, Kim S, Baek SH, Kim JH, Lee SR, Kim JR. Overexpression of mitochondrial thioredoxin reductase and peroxiredoxin III in hepatocellular carcinomas. Anticancer Res. 2002;22:3331–3335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Karihtala P, Mäntyniemi A, Kang SW, Kinnula VL, Soini Y. Peroxiredoxins in breast carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:3418–3424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ummanni R, Barreto F, Venz S, Scharf C, Barett C, Mannsperger HA, Brase JC, Kuner R, Schlomm T, Sauter G, et al. Peroxiredoxins 3 and 4 are overexpressed in prostate cancer tissue and affect the proliferation of prostate cancer cells in vitro. J Proteome Res. 2012;11:2452–2466. doi: 10.1021/pr201172n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kim YS, Lee HL, Lee KB, Park JH, Chung WY, Lee KS, Sheen SS, Park KJ, Hwang SC. Nuclear factor E2-related factor 2 dependent overexpression of sulfiredoxin and peroxiredoxin III in human lung cancer. Korean J Intern Med. 2011;26:304–313. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2011.26.3.304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Hu JX, Gao Q, Li L. Peroxiredoxin 3 is a novel marker for cell proliferation in cervical cancer. Biomed Rep. 2013;1:228–230. doi: 10.3892/br.2012.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Schulte J. Peroxiredoxin 4: A multifunctional biomarker worthy of further exploration. BMC Med. 2011;9:137. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Okado-Matsumoto A, Matsumoto A, Fujii J, Taniguchi N. Peroxiredoxin IV is a secretable protein with heparin-binding properties under reduced conditions. J Biochem. 2000;127:493–501. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a022632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Roumes H, Pires-Alves A, Gonthier-Maurin L, Dargelos E, Cottin P. Investigation of peroxiredoxin IV as a calpain-regulated pathway in cancer. Anticancer Res. 2010;30:5085–5089. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Ikeda Y, Nakano M, Ihara H, Ito R, Taniguchi N, Fujii J. Different consequences of reactions with hydrogen peroxide and t-butyl hydroperoxide in the hyperoxidative inactivation of rat peroxiredoxin-4. J Biochem. 2011;149:443–453. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvq156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Zhu L, Yang K, Wang X, Wang X, Wang CC. A novel reaction of peroxiredoxin 4 towards substrates in oxidative protein folding. PLoS One. 2014;9:e105529. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ishii T, Warabi E, Yanagawa T. Novel roles of peroxiredoxins in inflammation, cancer and innate immunity. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2012;50:91–105. doi: 10.3164/jcbn.11-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Mishra M, Jiang H, Wu L, Chawsheen HA, Wei Q. The sulfiredoxin-peroxiredoxin (Srx-Prx) axis in cell signal transduction and cancer development. Cancer Lett. 2015;366:150–159. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Chen JH, Ni RZ, Xiao MB, Guo JG, Zhou JW. Comparative proteomic analysis of differentially expressed proteins in human pancreatic cancer tissue. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2009;8:193–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Pritchard C, Mecham B, Dumpit R, Coleman I, Bhattacharjee M, Chen Q, Sikes RA, Nelson PS. Conserved gene expression programs integrate mammalian prostate development and tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2009;69:1739–1747. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Chang KP, Yu JS, Chien KY, Lee CW, Liang Y, Liao CT, Yen TC, Lee LY, Huang LL, Liu SC, et al. Identification of PRDX4 and P4HA2 as metastasis-associated proteins in oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma by comparative tissue proteomics of microdissected specimens using iTRAQ technology. J Proteome Res. 2011;10:4935–4947. doi: 10.1021/pr200311p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Karihtala P, Kauppila S, Soini Y, Arja-Jukkola-Vuorinen Oxidative stress and counteracting mechanisms in hormone receptor positive, triple-negative and basal-like breast carcinomas. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:262. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Karihtala P, Soini Y, Vaskivuo L, Bloigu R, Puistola U. DNA adduct 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine, a novel putative marker of prognostic significance in ovarian carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2009;19:1047–1051. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181ad0f0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Yi N, Xiao MB, Ni WK, Jiang F, Lu CH, Ni RZ. High expression of peroxiredoxin 4 affects the survival time of colorectal cancer patients, but is not an independent unfavorable prognostic factor. Mol Clin Oncol. 2014;2:767–772. doi: 10.3892/mco.2014.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Wei Q, Jiang H, Xiao Z, Baker A, Young MR, Veenstra TD, Colburn NH. Sulfiredoxin-Peroxiredoxin IV axis promotes human lung cancer progression through modulation of specific phosphokinase signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:7004–7009. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013012108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Palande KK, Beekman R, van der Meeren LE, Beverloo HB, Valk PJ, Touw IP. The antioxidant protein peroxiredoxin 4 is epigenetically down regulated in acute promyelocytic leukemia. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16340. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Knoops B, Goemaere J, Van der Eecken V, Declercq JP. Peroxiredoxin 5: Structure, mechanism, and function of the mammalian atypical 2-Cys peroxiredoxin. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;15:817–829. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]