Abstract

Introduction

The degree and duration of response to epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitors in EGFR mutated lung cancer are heterogeneous. We hypothesized that the concurrent genomic landscape of these tumors, which is currently unknown in view of the prevailing single gene assay diagnostic paradigm in clinical practice, could play a role in clinical outcomes and/or mechanisms of resistance.

Methods

We retrospectively probed our institutional lung cancer database for tumors with EGFR kinase domain mutations that were also evaluated by more comprehensive molecular profiling, and evaluated tumor response to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs).

Results

Out of 171 EGFR mutated tumor-patient cases, 20 were sequenced using at least a limited comprehensive genomic profiling platform. 50% harbored concurrent TP53 mutation, 10% PIK3CA mutation, 5% PTEN mutation, among others. The response rate to EGFR TKIs, the median progression-free survival (PFS) to TKIs, the percentage of EGFR-T790M TKI resistance and survival had higher trends in EGFR mutant/TP53 wild-type cases when compared to EGFR mutant/TP53 mutant tumors (all p>0.05 without statistical significance); with a significantly longer median PFS in EGFR-exon 19 deletion mutant/TP53 wild-type cancers treated with 1st generation EGFR TKIs (p=0.035).

Conclusions

Concurrent mutations, specifically TP53, are common in EGFR mutated lung cancer and may alter clinical outcomes. Additional cohorts will be needed to determine if comprehensive molecular profiling adds clinically relevant information to single gene assay identification in oncogene-driven lung cancers.

Keywords: mutation, lung cancer, adenocarcinoma, EGFR, TP53, PIK3CA, PTEN, kinase inhibitor, erlotinib

INTRODUCTION

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) are the evidenced-based first line palliative therapy option for advanced non-small-cell lung cancers (NSCLCs) that harbor the most common forms of EGFR mutations: exon 19 deletions or the exon 21 L858R [1]. The overall response rate (ORR), progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) times favor 1st (gefitinib, erlotinib) and 2nd (afatinib) generation EGFR TKIs when compared to chemotherapy [1]. However, there is significant heterogeneity in individual patient outcomes. Some cases may respond for years while other may only respond for a few weeks, or even progress outright. The main biological mechanisms of resistance to 1st/2nd generation EGFR TKIs, either the EGFR-T790M mutation or oncogene bypass tracks, are also heterogeneous within different patients and even within tumors of a single patient [1–3].

It is likely that genetic, epigenetic and pharmacokinetic variations explain the marked diversity of clinical outcomes observed in clinical practice. Indeed, The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) of early stage lung adenocarcinoma samples disclosed that EGFR mutations are concurrently present with mutations in tumor suppressor genes and oncogenes to varying degrees [4], and spatial-temporal tumor analyses have disclosed that EGFR mutated NSCLCs follow an evolutionary pathway with significant intratumor and/or intertumor heterogeneity [4]. Current guidelines and drug approval companion diagnostics favor limited single gene assay analysis for EGFR mutations in NSCLC, which has restricted our knowledge of how the most common concurrent tumor suppressor and/or oncogene mutations may impact the clinical outcomes of EGFR TKI monotherapy. Therefore, in this report we sought to probe the landscape of genomic changes that can be identified in advanced EGFR mutated NSCLC using commercially-available comprehensive molecular profiling platforms and correlate the co-mutation profile with response/resistance to EGFR TKIs.

METHODS

Tumor and data collection

Patient-tumor pairs followed at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) with a diagnosis of lung cancer were registered through ongoing Institutional Review Board-approved studies [5, 6]. Pathologic data, tumor genotype, type/dose of EGFR TKI, radiographic images and survival were assembled from retrospective chart extraction. Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) was utilized (version 1.0 in cases managed prior to 2010 and version 1.1 after 2010). PFS and OS were calculated from time of initiation of an EGFR TKI. Data was collected and managed using the REDCap electronic data capture held at BIDMC. The data cut-off for outcomes was May 7th 2016.

In addition, the 2014 TCGA lung adenocarcinoma mutation database [4] was reviewed and collated for EGFR genotypes and co-existing mutations using cBioPortal (http://www.cbioportal.org/index.do).

Tumor genomic analyses

EGFR, exons 18 to 21, single gene Sanger sequencing assays were performed in all diagnostic tumor samples [5]. Comprehensive genomic profiling - of selected cases beyond routine clinical care - was performed using two different commercially-available platforms: SNaPshot-NGS or JAX-Cancer Treatment Profile, as described previously [7, 8]. The gene set and exons that overlap between these next generation sequencing assays are depicted in Supplementary Table 1 and only this set was used for identification of concurrent mutation burden. We report the presence and absence of co-existing mutations in the TKI-naïve setting. Clinical and pathological characteristics of EGFR mutated tumors are detailed in Supplementary Table 2.

Statistical methods

Fisher’s exact test was used to compare categorical variables. All p-values reported are two-sided, and tests were conducted at the 0.05 significance level. PFS and OS were analyzed using the Kaplan–Meier method and the log-rank test (Mantel-Cox) was used to compare differences in distributions. Statistical analyses and curves were performed with the GraphPad Prism 6 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

RESULTS

Concurrent genomic changes identified using comprehensive genomic profiling in EGFR mutated NSCLC

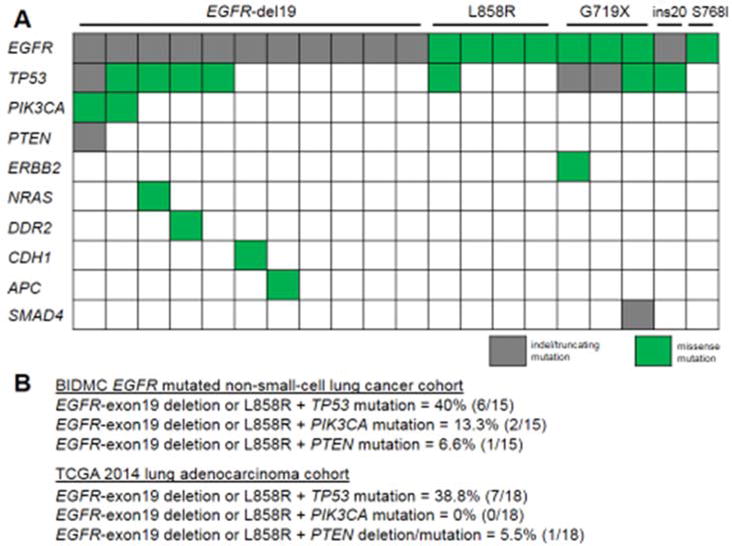

Our BIDMC database consisted of 171 EGFR mutated tumors identified mostly by single gene assay. Of these, 20 patient-tumor pairs were also analyzed by comprehensive genomic profiling. The majority of these tumors harbored common EGFR mutations in exons 19 (deletions) or L858R (15/20, 75%). The most common concurrent genomic alteration was tumor protein P53 (TP53), which was present in 10/20 (50%) of all EGFR mutated tumors (Figure 1A) and in 6/15 (40%) of tumors with EGFR-exon 19 deletions or L858R (Figure 1B). The second most common co-existing gene mutation was in phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase, catalytic subunit alpha (PIK3CA), present in 2/20 (10%) of all EGFR mutated tumors (Figure 1A) and in 2/15 (13.3%) of the tumors with EGFR-exon 19 deletions or L858R (Figure 1B). A plentitude of other gene mutations, including phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), were identified at a frequency of <10% (Figure 1A). The frequencies of TP53, PIK3CA and PTEN aberrations co-occurring with EGFR mutations identified at BIDMC were similar to those previously reported in TCGA (Figure 1B). The spectrum of TP53 mutations (truncating or missense mutations) that were identified in the TCGA’s EGFR mutated lung adenocarcinoma cohort are depicted in Figure 2A. The TP53 mutations identified at BIDMC affected similar amino-acids as the TCGA cohort (Figure 2A and Supplementary Table 2).

Figure 1. Concurrent mutations identified in EGFR mutated lung cancers analyzed by focused comprehensive genomic profiling panels.

A Type of EGFR mutation and concurrent mutation profile of tumors. The graphic representation highlights indel/truncating mutation or missesense mutation types. B. Frequency of co-occurring EGFR-exon 19 deletion or L858R with TP53, PIK3CA and PTEN in the BIDMC and TCGA cohorts.

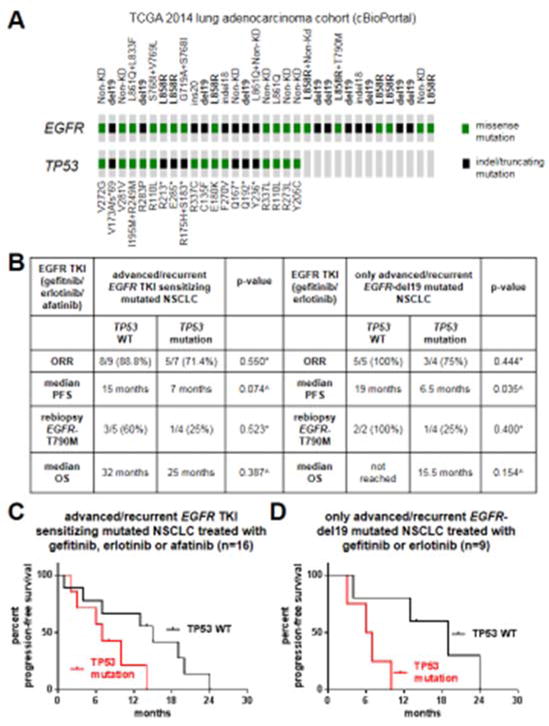

Figure 2. TP53 mutations and how they affect clinical outcomes or resistance to EGFR kinase inhibitors.

A. Graphic representation of the spectrum of EGFR and TP53 mutations identified in the 2014 TCGA lung adenocarcinoma cohort (data obtained using cBioPortal). B. Response (ORR, median PFS, median OS and rebiopsy results) of EGFR TKI-treated patients whose tumors harbored or not a concurrent TP53 mutation. C. Kaplan-Meier PFS curve of patients with EGFR mutated tumors with or without TP53 mutations and treated with 1st/2nd generation EGFR TKIs. D. Kaplan-Meier PFS curve of patients with EGFR-exon19 deletion mutated tumors with or without TP53 mutations treated with 1st generation EGFR TKIs. *, p-value calculated using Fisher’s exact test. ^, p-values obtained using the log-rank test.

Clinical outcomes and mechanisms of resistance to EGFR TKIs

We further evaluated each patient’s response to EGFR TKIs and subsequent mechanisms of resistance (Supplementary Table 2), with a specific focus on how TP53 mutations impacted these parameters (Figure 2B and 2C). Out of all patients with advanced (stage IV or recurrent) NSCLCs with EGFR TKI sensitizing EGFR mutations that received gefitinib, erlotinib or afatinib (n=16), the ORR, median PFS and median OS were longer in patients whose tumors had wild-type (WT) TP53 when compared to patients whose tumors were TP53 mutated; although the differences did not reach statistical significance (Figure 2B and 2C).

When we only analyzed the most TKI responsive and common EGFR mutation subgroup, exon 19 deletions, the same degree of improved outcomes in tumors with concurrent EGFR mutation/TP53 WT status versus EGFR mutation/TP53 mutation status was noted when only studying patients that received 1st generation EGFR TKIs (Figure 2B). The most noticeable difference was in median PFS times, where EGFR mutated/TP53 WT cases had a median PFS of 19 months versus a median PFS of 6.5 months for EGFR mutated/TP53 mutated cases (p=0.035); as depicted in Figure 2D.

Nine patients underwent rebiopsy upon progression on EGFR TKIs. We noted that rebiopsy specimens from patients whose tumors initially lacked TP53 mutations and with acquired resistance to 1st/2nd generations EGFR TKIs had a numerically, albeit non-statistically significant, higher rate of EGFR-T790M (Figure 2B).

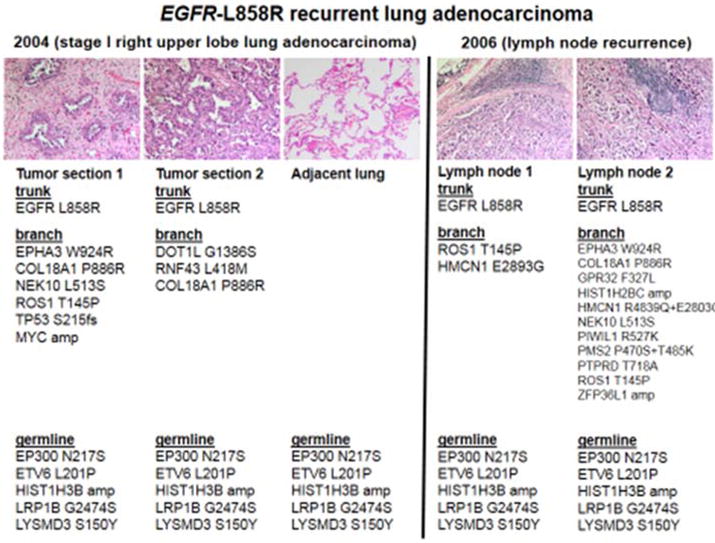

Intratumor heterogeneity of concurrent mutations and EGFR mutations

To attempt to highlight the spatial-temporal relationship and nature of concurrent mutations with presumed trunk-type EGFR mutation, we were able to study a case in which multiple samples were available for comprehensive genomic profiling (Figure 3). This particular case of recurrent EGFR-L858R mutated lung adenocarcinoma was initially diagnosed as a stage I tumor with recurrence into mediastinal nodes and extra-thoracic sites two years after surgical resection. The mediastinal node recurrence was the tissue used for the initial single gene assay diagnosis of L858R and was noted to be WT for TP53, PIK3CA and PTEN using the robust JAX-Cancer Treatment Profile [8] comprehensive genomic profiling assay (Figure 3). The analyses of multiple sites of the original tumor, adjacent normal lung tissue and other mediastinal node recurrences disclosed heterogeneity in branch-type mutations plus the presence of germline mutations (Figure 3). Of most interest, one of the sections of the original tumor (but not all sections) harbored a TP53 mutation that was not present in the recurrent/metastatic tumors; suggesting that some TP53 mutations are branch-type mutations and that the current paradigm of a single biopsy analysis may be unable to highlight the complete subclonal intratumor heterogeneity of advanced cancers.

Figure 3. Spatial-temporal heterogeneity of molecular alterations in one case of recurrent EGFR-L858R mutated lung adenocarcinoma prior to EGFR inhibitor therapy.

In this case of EGFR mutated lung cancer, the original right upper lobectomy for a 2.0 cm invasive lung adenocarcinoma demonstrated a mixture of acinar (tumor section 1) and lepidic (tumor section 2) patterns. Both harbored the same EGFR mutation (L858R) as well as shared proposed germline mutations (also observed in a section of adjacent uninvolved lung parenchyma); however, significant heterogeneity was observed in branch-type mutations, including TP53 only on tumor section 1 but not section 2. The recurrent metastatic adenocarcinoma found in two separate supraclavicular lymph nodes (lymph node 1 and 2) were morphologically similar and once again demonstrated the same driver EGFR-L858R mutation and shared germline mutations, but displayed significant heterogeneity in the branch-type mutations.

DISCUSSION

The use of comprehensive genomic profiling in clinical specimens was able to identify a significant number of concurrent mutations in EGFR mutated lung cancers, confirming the TCGA lung adenocarcinoma data that showed that TP53, PIK3CA and PTEN mutations are frequent concurrent abnormalities [4]. Although preclinical models, from our group and others, have disclosed that certain genomic changes (such as PTEN deletion/inactivation and/or PIK3CA mutation/activation/overexpression that can activate downstream pathways engaged by EGFR) can alter the pattern of response to EGFR TKIs [9], it continues to be unclear if these changes impact outcomes in the clinic due to the potential impact of intratumor heterogeneity and subclonal sampling of a single biopsy specimen [10]. Notably, examination of the spatial-temporal relationship of multiple specimens from one patient in our cohort disclosed that even TP53 mutations may occur in only a minor subclone of one tumor area and not in other tumors, while the driver EGFR mutation seems to be present in all specimens (indicative of a trunk-type mutation). We also observed that even tumors with possible activating PIK3CA, neuroblastoma RAS viral oncogene homolog (NRAS) or discoidin domain receptor tyrosine kinase 2 (DDR2) mutations were initially responsive to EGFR TKIs in the context of a driver EGFR mutation.

Despite the aforementioned concerns with intratumor heterogeneity, other groups have recently similarly reported in abstract format [11, 12] that co-occurrence of TP53 mutation with an EGFR activating (TKI sensitizing) mutation in a clinical biopsy specimen may lead to inferior ORR, PFS, and OS in EGFR TKI-treated patients. Our cohort was limited by the small numbers of cases and the retrospective analysis, both of which may have limited the ability to show statistically significant differences in outcomes. Somatic mutations of TP53 and inactivation of the TP53 protein is a pervasive event across all cancer subtypes, as TP53 is as a key tumor suppressor that has critical anti-proliferative functions [13]. The complete loss of TP53 function can accelerate the transforming potential of driver oncogenes in lung cancers [14] and hamper tumor response to cytotoxic chemotherapy [14], radiotherapy, and/or EGFR inhibitors [15]. The data on ORR, PFS, and OS presented here should be viewed as hypothesis generating. Other series will be needed to determine if inactivating TP53 mutations (or measurements of TP53 protein levels) and other genomic changes can be established as actionable predictive and/or prognostic biomarkers in the management of advanced NSCLC harboring EGFR mutations.

To the best of our knowledge, ours is the first cohort to show a trend towards a decrease rate of EGFR-T790M as a mechanism of resistance to 1st/2nd generation EGFR TKIs in tumors with concurrent TP53 mutations. Although a biological explanation for this observation is not apparent in preclinical models, it is possible that the absence of TP53 mutations is a marker of a tumor with fewer genomic escape pathways that may need to mutate the EGFR signaling apparatus to bypass EGFR TKIs; hence a higher rate of EGFR-T790M. Conversely, more genomic complex tumors (EGFR and TP53 concurrently mutated tumors) may be better equipped to activate alternate proliferative pathways that bypass EGFR as a target.

In summary, our small cohort highlights that EGFR mutated tumors have significant inter and intratumor heterogeneity with concurrent presence of important cancer-associated gene mutations. Some of the most common of these co-occurring changes, including TP53 mutations, may alter clinical outcomes of EGFR TKI-treated cases. Additional cohorts will be needed to determine if routine comprehensive molecular profiling adds predictive and/or prognostic information to the contemporary single gene assay approach in oncogene-driven lung cancers.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

-

-

EGFR mutations are identified concurrently with other genomic events

-

-

The impact of concurrent mutations (TP53, PIK3CA, PTEN etc) on inhibitor response is unknown

-

-

TP53 mutations commonly co-occur with EGFR mutations, and may affect clinical outcomes

Acknowledgments

This work was funded in part through an American Cancer Society grant RSG 11-186 (DBC), and National Cancer Institute grants P50CA090578 (DBC), R01CA169259 (SSK) and R21CA17830 (SSK).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Daniel B. Costa has received consulting fees and honoraria from Pfizer Inc (unrelated to the current work), consulting fees from Ariad Pharmaceuticals (unrelated to the current work), and honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim (unrelated to the current work).

Susan M. Mockus, Vanessa Spotlow, Honey Reddi, and Joan Malcolm are are employees of The Jackson Laboratory that developed the JAX-Cancer Treatment Profile genomic test (related to this work).

Deepa Rangachari, Mark S. Huberman, and Susumu S. Kobayashi have no conflicts to disclose.

No other conflict of interest is stated.

References

- 1.Costa DB, Kobayashi SS. Whacking a mole-cule: clinical activity and mechanisms of resistance to third generation EGFR inhibitors in EGFR mutated lung cancers with EGFR-T790M. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2015;4:809–15. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2218-6751.2015.05.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kobayashi S, Boggon TJ, Dayaram T, et al. EGFR mutation and resistance of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:786–92. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa044238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nguyen KS, Kobayashi S, Costa DB. Acquired resistance to epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors in non-small-cell lung cancers dependent on the epidermal growth factor receptor pathway. Clin Lung Cancer. 2009;10:281–9. doi: 10.3816/CLC.2009.n.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Collisson EA, Campbell JD, Brooks AN, Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network Comprehensive molecular profiling of lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2014;511:543–50. doi: 10.1038/nature13385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.VanderLaan PA, Yamaguchi N, Folch E, et al. Success and failure rates of tumor genotyping techniques in routine pathological samples with non-small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2014;84:39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2014.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yasuda H, Park E, Yun CH, et al. Structural, biochemical, and clinical characterization of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) exon 20 insertion mutations in lung cancer. Sci Transl Med. 2013;5:216ra177. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zheng Z, Liebers M, Zhelyazkova B, et al. Anchored multiplex PCR for targeted next-generation sequencing. Nat Med. 2014;20:1479–84. doi: 10.1038/nm.3729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ananda G, Mockus S, Lundquist M, et al. Development and validation of the JAX Cancer Treatment Profile for detection of clinically actionable mutations in solid tumors. Exp Mol Pathol. 2015;98:106–12. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2014.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Costa DB, Halmos B, Kumar A, et al. BIM mediates EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor-induced apoptosis in lung cancers with oncogenic EGFR mutations. PLoS Med. 2007;4:1669–79. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McGranahan N, Favero F, de Bruin EC, Birkbak NJ, Szallasi Z, Swanton C. Clonal status of actionable driver events and the timing of mutational processes in cancer evolution. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:283ra54. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaa1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu HA, Jordan E, Ni A, Feldman D, et al. Concurrent genetic alterations identified by next-generation sequencing in pre-treatment, metastatic EGFR-mutant lung cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:abstr 9053. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ulivi P, Canale M, Petracci E, Chiadini E, et al. Role of TP53 mutations in predicting response to TKI treatment in EGFR-mutated NSCLC patients. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:abstr 9052. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olivier M, Hollstein M, Hainaut P. TP53 mutations in human cancers: origins, consequences, and clinical use. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a001008. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen Z, Cheng K, Walton Z, et al. A murine lung cancer co-clinical trial identifies genetic modifiers of therapeutic response. Nature. 2012;483:613–7. doi: 10.1038/nature10937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang S, Benavente S, Armstrong EA, Li C, Wheeler DL, Harari PM. p53 modulates acquired resistance to EGFR inhibitors and radiation. Cancer Res. 2011;71:7071–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.