Abstract

The antibiotic phosphinothricin tripeptide (PTT) consists of two molecules of l-alanine and one molecule of the unusual amino acid phosphinothricin (PT) which are nonribosomally combined. The bioactive compound PT has bactericidal, fungicidal, and herbicidal properties and possesses a C—P—C bond, which is very rare in natural compounds. Previously uncharacterized flanking and middle regions of the PTT biosynthetic gene cluster from Streptomyces viridochromogenes Tü494 were isolated and sequenced. The boundaries of the gene cluster were identified by gene inactivation studies. Sequence analysis and homology searches led to the completion of the gene cluster, which consists of 24 genes. Four of these were identified as undescribed genes coding for proteins that are probably involved in uncharacterized early steps of antibiotic biosynthesis or in providing precursors of PTT biosynthesis (phosphoenolpyruvate, acetyl-coenzyme A, or l-alanine). The involvement of the genes orfM and trs and of the regulatory gene prpA in PTT biosynthesis was analyzed by gene inactivation and overexpression, respectively. Insight into the regulation of PTT was gained by determining the transcriptional start sites of the pmi and prpA genes. A previously undescribed regulatory gene involved in morphological differentiation in streptomycetes was identified outside of the left boundary of the PTT biosynthetic gene cluster.

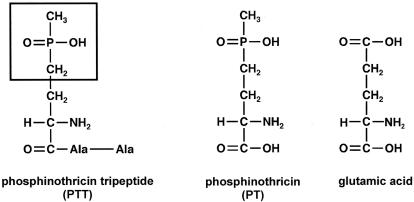

The discovery of a new peptide antibiotic was reported for Streptomyces viridochromogenes in 1972 (3) and for Streptomyces hygroscopicus in 1973 (19). The antibiotic, named phosphinothricin tripeptide (PTT) or bialaphos, consists of two molecules of l-alanine and one molecule of the unusual amino acid phosphinothricin (PT). The bioactive compound l-PT, a structural analogue of glutamic acid (Fig. 1), acts as a competitive inhibitor of glutamine synthetases (3) and has bactericidal, fungicidal, and herbicidal properties. Basta, the ammonium salt of l/d-PT (Hoechst Hoe 039866), and Herbiace, the tripeptide bialaphos, are used as broad-spectrum agricultural herbicides. Basta-resistant transgenic plants have been generated (43) by use of the S. viridochromogenes PTT resistance gene (pat) (38), which is part of the PTT biosynthetic cluster.

FIG. 1.

Chemical structure of PTT and related compounds.

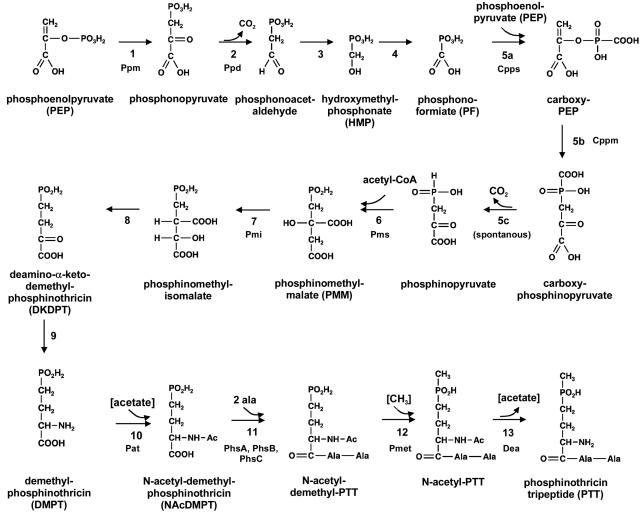

The biosynthesis of bialaphos in S. hygroscopicus has been investigated by analyses of accumulated and converted intermediates in mutants that are unable to produce PTT. This has led to the proposal of a hypothetical pathway (41) (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Postulated PTT biosynthetic pathway (according to reference 41).

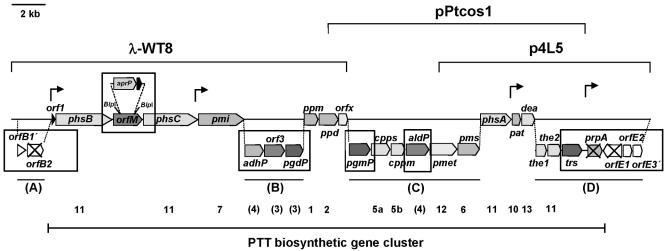

The tripeptide PTT is assembled nonribosomally by peptide synthetases. For S. viridochromogenes, three peptide synthetase genes—phsA, phsB, and phsC—have been identified. phsB and phsC are located approximately 20 kb upstream of phsA (Fig. 3) and are interspaced by an open reading frame (ORF) of unknown function, orfM (35). The inactivation of phsA, phsB, and phsC by gene replacement mutagenesis results in non-PTT-producing mutants (33, 35). Each of the encoded proteins represents one functional domain of a peptide synthetase that is required for the activation and condensation of one amino acid. The PhsA protein is involved in the initial step of PTT formation, the activation of the PT precursor N-acetyl-demethylphosphinothricin (N-Ac-DMPT) (10, 33). PhsB and PhsC each activate an alanine residue (10, 35).

FIG. 3.

Genetic organization of the complete PTT biosynthetic gene cluster. (A to D) Newly characterized DNA regions described in this paper. The deduced ORFs are drawn to scale. phsA, phosphinothricin tripeptide synthetase A gene; phsB, phosphinothricin tripeptide synthetase B gene; phsC, phosphinothricin tripeptide synthetase C gene; pmi, phosphinomethyl malate isomerase gene; ppm, PEP phosphomutase gene; ppd, phosphonopyruvate decarboxylase gene; cppm, carboxy-PEP phosphonomutase gene; cpps, carboxy-PEP synthase gene; pmet, P-methylase gene; pms, phosphinomethylmalic acid synthase gene; dea, deacetylase gene; pat, phosphinothricin N-acetyltransferase gene; the1 and the2, thioesterase genes; trs, putative transporter gene; prpA, phosphinothricin tripeptide biosynthesis regulatory gene; orf1, mbtH-like gene; adhP, putative alcohol dehydrogenase gene; orf3, gene of unknown function; pgdP, putative d-3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase gene; pgmP, putative phosphoglycerate mutase gene; orfM, putative membrane protein gene; orfx, putative nucleotidyltransferase gene; and aldP, putative aldehyde dehydrogenase gene. The positions of the overlapping inserts of cosmids pPtcos1 and p4L5 (approximately 12 kb of the cosmid insert is shown) and the phage clone λ-WT8 are shown. The insertion site of the aprP resistance cassette in the orfM gene is indicated. Genes that were inactivated by disruption are indicated by cross marks. The locations of promoter regions within the cluster are indicated by arrows. The numbers of the biosynthetic steps carried out by the encoded proteins are indicated below the respective genes; hypothetical step numbers are shown in parentheses. The new PTT biosynthetic genes analyzed in this work are boxed.

The alanine residues of the tripeptide are derived by primary metabolism, whereas the nonproteinogenic amino acid PT, synthesized via the intermediate DMPT (Fig. 2), is derived by secondary metabolite biosynthesis. According to the postulated biosynthetic pathway, PT is generated from two molecules of phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP), one molecule of acetyl-coenzyme A, and one methyl group of methylcobalamin in 13 biosynthetic steps (Fig. 2). The S. viridochromogenes genes ppm and ppd encode PEP phosphomutase (step 1) and phosphonopyruvate decarboxylase (step 2), respectively (34). The aconitase-like gene pmi encodes a protein that specifically catalyzes the isomerization of the intermediate phosphinomethylmalate (step 7) (Fig. 2) (11).

Subregions of the PTT biosynthetic gene cluster have been identified and characterized (Fig. 3), but the entire sequence of the cluster has not yet been determined.

Here we present the completion of the PTT biosynthetic gene cluster. Furthermore, by performing gene inactivation and overexpression experiments, we examined the roles of the biosynthetic genes orfM, encoding a putative membrane protein; trs, encoding a hypothetical transporter protein; and prpA, a regulatory gene.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

S. viridochromogenes Tü494 (3) was used for phage and cosmid library construction and for the generation of gene replacement and gene disruption mutants. Streptomyces lividans TK23 (18) (Table 1) was used as a PTT-sensitive expression host for analyses of the function of the trs gene. The morphological and physiological properties of wild-type S. viridochromogenes and of generated mutants were examined with yeast malt medium (33). Liquid cultures were incubated at 30°C in 100 ml of medium in 500-ml Erlenmeyer flasks (with steel springs) on an orbital shaker (180 rpm). Spores were isolated as described previously (15). Escherichia coli XL1 Blue (6) was the host strain for library construction and subsequent DNA manipulation.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains, cosmids, and plasmids

| Strain, phage, cosmid or plasmid | Relevant genotype and phenotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| S. viridochromogenes Tü494 | PTT-producing wild type | 3 |

| S. lividans TK23 | spec | 18 |

| E. coli XL1 Blue | recA1 endA1 gyrA96 thi-1 hsdR17 supE44 relA1 lac [F′, proAB lac1qZΔ M15Tn10 (Tet)] | 6 |

| Cosmids | ||

| pOJ446 | Streptomyces-E. coli cosmid shuttle vector, Aprar | 18 |

| pPtcos1 | Supercos1 carrying approximately 16 kb of the PTT biosynthetic gene cluster | 1 |

| pKC505 | Streptomyces-E. coli cosmid shuttle vector, Aprar | 29 |

| p4L5 | pKC505 carrying approximately 10 kb of the PTT biosynthetic gene cluster | This study |

| Phage | ||

| λ-WT8 | λ phage clone carrying approximately 20 kb of the PTT biosynthetic gene cluster from S. viridochromogenes | 34 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pDS204 | pK19 carrying orf1, phsB, orfM, and phsC on an 8.9-kb EcoR1/Kpn1 fragment of the PTT biosynthetic gene cluster | 35 |

| pDS301 | pDS204 derivative, a 0.7-kb BlpI fragment was replaced by a 1.8-kb EcoRV/StuI fragment of pEH13 (aprP resistance cassette) | This study |

| pDS400 | pEM4 carrying the trs gene located on a 2.4-kb AatII/BamHI fragment of the PTT biosynthetic gene cluster | This study |

| pEH13 | pUC21 derivative carrying the apramycin/aprP resistance cassette | 11 |

| pEM4 | Streptomyces-E. coli shuttle vector, tsr ermEp | 27 |

| pKM100 | pGEMTeasy carrying an internal 0.5-kb orfB2 fragment | This study |

| pKM101 | Litmus 38 carrying an internal 0.7-kb MluI/NaeI fragment of orfE1 | This study |

| pKM102 | pK19 carrying an internal 0.6-kb SphI/SacI fragment of prpA | This study |

| pKM103 | pGM8 derivative carrying pKM100 as an SpeI fragment | This study |

| pKM104 | pGM8 derivative carrying pKM101 as a HindIII fragment | This study |

| pKM105 | pK19 carrying prpA located on a 1.0-kb DNA fragment of the PTT biosynthetic gene cluster | This study |

| pKM106 | pGM9 derivative carrying pKM102 as a HindIII fragment | This study |

| pKM107 | pEM4 carrying prpA as a 1.0-kb EcoRI/PstI fragment of pKM105 | This study |

Cloning, restriction mapping, and in vitro manipulation of DNA.

DNA was isolated and manipulated as described previously (15, 31). Restriction endonucleases were used according to the suppliers' instructions. E. coli was transformed by the CaCl2 method (31). Plasmids were introduced into Streptomyces strains by polyethylene glycol-mediated transformation (18). A cosmid library was constructed with the E. coli-Streptomyces shuttle vector pKC505 (29) or Supercos1 (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.). A λ phage library was created with the vector Lambda FIX-II (Stratagene). pK19, pUC18, and pBlueskript SK(+) were routinely used as vectors for subcloning and sequencing. Serial deletion subclones were generated by use of a double-stranded nested deletion kit from Amersham Biosciences (Uppsala, Sweden).

DNA sequencing and analysis.

DNAs were sequenced on an ALF DNA sequencer (Pharmacia, Freiburg, Germany) or an ABI sequencer. Sequences were compiled with DNASIS (Pharmacia). ORFs were identified with the codon usage program of Staden and McLachlan (4, 37) and with Artemis (30). The programs BLAST (2), CLUSTAL W (42), and Genedoc (23) were used for homology searches and multiple sequence alignments. The program Tmpred (14) was used to identify possible membrane-spanning regions. Transmembrane helices were predicted by the dense alignment surface method (7).

Gene disruption mutagenesis of orfB2, orfE1, and prpA.

An internal fragment of orfB2 (496 bp) was amplified by a PCR using the primers orfB2/1 (5′-GGACTGCGCGAGCGCGTCGCG-3′) and orfB2/2 (5′-CGCCGTCATGAGTGTCTCGGCGAG-3′). This DNA fragment was cloned into the vector pGEMTeasy (Promega, Madison, Wis.), resulting in plasmid pKM100. An internal MluI/NaeI fragment of orfE1 (706 bp) was cloned into the vector Litmus38 (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.), resulting in plasmid pKM101. An internal SphI/SacI fragment of prpA (556 bp) was subcloned into pK19, yielding pKM102. The SpeI fragment of pKM100 and the HindIII fragment of pKM101 were each fused with pGM8 (22), resulting in plasmids pKM103 and pKM104, respectively; the HindIII fragment of pKM102 was fused with pGM9 (22), resulting in pKM106. S. viridochromogenes was transformed with these plasmids, and the corresponding genes were disrupted as described previously (33). The genotype of the mutants was verified by Southern hybridization or PCR. PTT production was determined by use of an antibiotic production test with Bacillus subtilis as a PTT-sensitive indicator strain, as described by Alijah et al. (1).

Gene replacement mutagenesis of orfM.

Plasmid pDS204, which carries an 8.9-kb EcoRI/KpnI fragment of the PTT biosynthetic gene cluster (orf1-phsB-orfM-phsC gene region) was digested with BlpI. An internal 0.7-kb BlpI DNA fragment of the orfM gene was replaced by the aprP resistance gene cassette (1.8-kb EcoRV/StuI fragment of pEH13), which carries the apramycin resistance gene and the constitutive promoter ermEp to drive the expression of downstream genes (11), resulting in plasmid pDS301. To avoid polar effects by disruption of an operon structure, we cloned the cassette in the transcriptional direction of the phsC gene. S. viridochromogenes was transformed with pDS301, and gene replacement mutagenesis of the orfM gene, verification of the mutant, and testing for PTT production were performed as described above.

Overexpression of the regulator gene prpA.

prpA was amplified by a PCR using the primers prpA1 (5′-AAAACTGCAGCACGGCTTTCAGAGGAGG-3′) and prpA2 (5′-CCGAATTCGTCACCCGCAGGCATGTC-3′) (the restriction sites used for cloning are underlined). The resulting fragment was cloned into pK19, yielding pKM105. The PstI/EcoRI fragment of pKM105 was cloned downstream of ermEp in the vector pEM4 (29), resulting in plasmid pKM107, which was introduced into wild-type S. viridochromogenes by transformation.

Western blot analysis of phsA expression in S. viridochromogenes.

The presence of the PhsA protein in crude extracts of S. viridochromogenes strains was examined by immunoblotting experiments using polyclonal antibodies raised against PhsA as described previously (33).

RNA preparation and primer extension experiments.

To investigate the transcription of the pmi and prpA genes, we isolated RNAs at several time points (24, 48, and 72 h) according to the method of Muschko et al. (21). The transcriptional start points of the pmi and prpA genes were mapped by use of the primer extension method described by Tesch et al. (40) and the synthetic oligonucleotides Ppmi (5′-GTGTTCCGAATTCTGGGAACCGTGCCTCAC-3′), which covers positions 1 to 29 (relative to the translational start site) on the complementary strand of the pmi gene, and PrpA1 (5′-GCGATTGGCACTGATGATCTGTGAGATCAC-3′), which covers positions 120 to 142 relative to the first translational start site on the complementary strand of the prpA gene. The generated DNA fragments were separated in 5% polyacrylamide-urea gels in parallel with dideoxy sequencing reaction samples. The nucleotide sequence was determined by the dideoxy chain termination method (32) with a T7 sequencing kit (Amersham Biosciences).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence data reported have been assigned accession no. X65195 in the EMBL data library.

RESULTS

Isolation and characterization of DNA fragments covering gaps in the PTT biosynthetic gene cluster.

The recombinant cosmid pPtcos1 and the phage clone λ-WT8, both of which carry PTT biosynthetic genes, were isolated previously (34, 44), and parts of the PTT biosynthetic gene cluster have been characterized. However, two gaps in the middle of the cluster and the left and right boundaries (see below) remained to be characterized.

A 2.2-kb fragment at the left boundary (Fig. 3A) and a 3.5-kb fragment (Fig. 3B) and 7.9-kb fragment (Fig. 3C) in the middle of the gene cluster from λ-WT8 or pPtcos1 were each subcloned by the use of BamHI, SacI, PstI, ScaI, or NotI and then were sequenced. The nucleotide sequences obtained revealed that the cloned inserts of pPtcos1 and λ-WT8 together do not cover the complete gene cluster, i.e., the right end was incomplete. Therefore, a new cosmid library was generated in the vector pOJ446 by use of a 3.4-kb BamHI fragment at the right end of pPtcos1 as a probe in Southern hybridization experiments. One cosmid, p4L5, was found that had an overlap of approximately 10 kb with cosmid pPtcos1 (Fig. 3). A 6.4-kb DNA fragment (Fig. 3D) of p4L5 was subcloned and sequenced.

Determination of the left and right boundaries of the cluster by gene disruption.

At the left boundary, adjacent to the previously identified PTT biosynthetic genes orf1 and phsB (Fig. 3A), two ORFs (orfB1′ and orfB2) were identified by in silico analysis. These ORFs encode proteins with high sequence similarities to proteins of unknown function from the non-PTT-producing organism Streptomyces coelicolor that are conserved in streptomycetes whose genome sequences have been determined (Table 2). At the right boundary downstream of the PTT biosynthesis regulatory gene prpA (see below) (Fig. 3D), three ORFs (orfE1, orfE2, and orfE3′) were found. These ORFs encode proteins with sequence similarities to a putative transport protein, a putative DNA-binding protein, and a formamidopyrimidine-DNA glycosylase, an enzyme involved in DNA repair processes, respectively, all from S. coelicolor. These similarities indicate that an involvement of orfB1′-orfB2 or orfE2-orfE3′ in the biosynthesis of the antibiotic is unlikely. Only for the transporter gene orfE1 could a role for the encoded protein in PTT biosynthesis be speculated. To verify the interpretation of the in silico data, we disrupted orfB2 and orfE1 by using plasmids pKM103 and pKM104 (Table 2), respectively. The resulting mutants were analyzed in a bioassay as described in Materials and Methods, and the inactivation of either of these genes had no effect on PTT biosynthesis. The orfE1 mutant did not show an obvious morphological phenotype, and the orfB2 mutant was defective in aerial mycelium formation.

TABLE 2.

Genes identified on the DNA region carrying the PTT biosynthetic gene cluster from S. viridochromogenes Tü494 and their deduced functions

| ORFa | No. of amino acids | Match in the database | Identity (%) | Accession no. of homologous proteins | Proposed function |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| orfB1 | 137 | Conserved hypothetical protein from S. coelicolor | 92 | AL353863 | Unknown |

| orfB2 | 297 | Conserved hypothetical protein from S. coelicolor | 73 | AL353863 | Unknown |

| orf1 | 69 | Conserved hypothetical protein from Azotobacter vinelandii; MbtH-like protein | 57 | ZP00092695.1 | Unknown (35) |

| phsB | 1,189 | NosA from Nostoc sp. strain GSV224 | 39 | AF204805.1 | Nonribosomal PTT synthesis (step 11) (10, 35) |

| orfM | 553 | No significant match | Unknown (35) | ||

| phsC | 1,086 | NosD from Nostoc sp. strain GSV224 | 38 | AAF17281.1 | Nonribosomal PTT synthesis (step 11) (10, 35) |

| pmi | 889 | TCA cycle aconitase AcnA from S. viridochromogenes | 53 | Y17270 | Isomerization of phosphinomethyl malate (step 7) (11) |

| adhP | 395 | Putative alcohol dehydrogenase from Amycolatopsis orientalis | 25 | AL078635.1 | Step 4a of PTT biosynthesis |

| orf3 | 432 | No significant match | Unknown | ||

| pgdP | 336 | d-3-Phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase from Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum | 34 | H69229 | Unknown |

| ppm | 313 | Phosphoenolpyruvate phosphomutase from S. hygroscopicus | 80 | D10016 | Step 1 of PTT biosynthesis (34) |

| ppd | 397 | Phosphonopyruvate decarboxylase from S. hygroscopicus | 74 | D37809 | Step 2 of PTT biosynthesis (34) |

| orfx | 184 | Nucleotidyltransferase from Pyrococcus furiosus DSM3638 | 29 | AAL80582.1 | Unknown (34) |

| pgmP | 447 | 2,3-Bisphosphoglycerate-independent phosphoglycerate mutase from Aeropyrum pernix | 35 | Q9YB12 | Unknown |

| cpps | 398 | Carboxyphosphoenolpyruvate synthase from S. hygroscopicus | 68 | D37878 | Step 5a of PTT biosynthesis |

| cppm | 296 | Carboxyphosphoenolpyruvate mutase from S. hygroscopicus | 96 | X67953 | Step 5b of PTT biosynthesis |

| aldP | 466 | Aldehyde dehydrogenase from Aquifex aeolicus | 36 | A70318 | Step 4b of PTT biosynthesis |

| pmet | 550 | P-methyltransferase from S. hygroscopicus | 88 | JC4112 | Step 12 of PTT biosynthesis |

| pms | 440 | 2-Phosphinomethylmalic acid synthase from S. hygroscopicus | 88 | AB029822 | Step 6 of PTT biosynthesis (44) |

| phsA | 622 | Actinomycin synthetase II from S. chrysomallus | 28 | AF047717.1 | Nonribosomal PTT synthesis (step 11) (11, 44) |

| pat | 183 | Phosphinothricin acetyl transferase from S. hygroscopicus | 79 | X17220 | PTT resistance protein (step 10) (38) |

| dea | 299 | Bialaphos acetyl hydrolase from S. hygroscopicus | 77 | M64783 | Deacetylase (step 13) (44) |

| the1 | 253 | Thioesterase 1 (orf3) from S. hygroscopicus | 80 | M64783 | Thioesterase (step 11 of PTT biosynthesis?) |

| the2 | 260 | Thioesterase 2 (orf2) from S. hygroscopicus | 66 | M64783 | Thioesterase (step 11 of PTT biosynthesis?) |

| trs | 412 | Citrate-proton symporter from Bacillus cereus ATCC 14579 | 39 | AAP07922.1 | Unknown |

| prpA | 301 | Regulatory protein BrpA from S. hygroscopicus | 58 | M64783.1 | PTT biosynthesis regulatory protein |

| orfE1 | 416 | Putative membrane transport protein from S. coelicolor | 40 | AL138598 | Unknown |

| orfE2 | 192 | Putative DNA-binding protein from S. coelicolor | 36 | NP630874.1 | Unknown |

| orfE3 | 190 | Formamidopyrimidine-DNA glycosylase from S. coelicolor | 35 | T35657 | DNA repair |

Genes whose function in S. viridochromogenes Tü494 was shown are underlined.

Defining the PTT biosynthetic gene cluster.

DNA sequencing and subsequent in silico analyses of the cosmid and phage clones pPtcos1, p4L5, and λ-WT8 and the disruption of orfB2 and orfE1 (described above) indicated that the PTT biosynthetic gene cluster begins with orf1, which is translationally coupled with phsB (35), and ends with prpA. Therefore, the PTT biosynthetic gene cluster covers approximately 33 kb and contains 24 biosynthetic genes (Fig. 3; Table 2).

Characterization of the middle and the right boundary of the PTT biosynthetic gene cluster.

Analyses of ORFs and sequence similarity searches led to the identification of several biosynthetic genes in the newly sequenced DNA regions.

On the 3.5-kb middle fragment (Fig. 3B), three putative genes were found, namely, adhP, orf3, and pgdP (Table 2).

Six ORFs (pgmP, cpps, cppm, aldP, pmet, and pms) were found in the 7.9-kb middle fragment (Fig. 3C; Table 2). The deduced proteins of cpps, cppm, pmet, and pms are similar in sequence to the gene products of the corresponding genes of the bialaphos biosynthetic gene cluster in S. hygroscopicus (Table 2) (41); therefore, the S. viridochromogenes genes very likely encode proteins with identical functions. The carboxyphosphoenolpyruvate (CPEP) synthase Cpps and the CPEP mutase Cppm of S. hygroscopicus catalyze the formation of CPEP and the subsequent rearrangement of the carboxyphosphono group in steps 5a and 5b, respectively, of PTT biosynthesis (12, 20) (Fig. 2). The phosphinomethylmalate synthase Pms of S. hygroscopicus is involved in step 6 of PTT biosynthesis (13), and the methylcobalamin-dependent P-methylating enzyme Pmet of S. hygroscopicus catalyzes the P-methylation of N-acetyldemethyl bialaphos in step 12 (16) (Fig. 2).

The 6.4-kb DNA fragment at the right boundary of the gene cluster (Fig. 3D) carries the four PTT biosynthetic genes the1, the2, trs, and prpA in addition to orfE1, orfE2, and orfE3′ (see above). the1 and the2 encode type II thioesterases (Table 2). The deduced sequences of the peptide synthetases involved in PTT biosynthesis do not contain a thioesterase domain (33, 35); one type II thioesterase is most likely involved in peptide release, whereas the other may have a proofreading activity. Such an activity for the regeneration of misprimed nonribosomal peptide synthetases by type II thioesterases has been shown for different enzymes from Bacillus spp. (36). The sequence of the deduced gene product of trs was shown to have similarities to citrate-proton symporters (Table 2) and to the corresponding protein of bialaphos biosynthesis, which is proposed to be involved in the secretion of PTT (28).

The last gene of the cluster, prpA, encodes a putative biosynthetic-pathway-specific transcriptional regulator. The ORF has two putative translational start codons (the first start codon is shown in Fig. 5), which would lead to proteins of 301 and 261 amino acids. The proteins have high sequence similarities to the gene product of the orthologous gene brpA from the bialaphos producer S. hygroscopicus (28). According to its amino acid sequence, PrpA can be identified as a response regulator of a two-component transcriptional control system, similar to those employed by diverse bacteria to transduce metabolic signals and activate gene expression. This type of activator usually contains an N-terminal receiver domain and a C-terminal effector domain. These proteins are activated by phosphorylation of a specific aspartate residue in the receiver domain and have a helix-turn-helix DNA-binding motif in the effector domain. PrpA contains a possible helix-turn-helix motif at its C terminus, but a receiver domain is absent; therefore, the mechanism by which PrpA is activated remains unknown. Three hydrophobic regions in the N-terminal region of BrpA from S. hygroscopicus that are probably involved in conferring protein-protein or protein-membrane contacts through hydrophobic interactions have been described (41). Similar regions were also found in the deduced amino acid sequence of PrpA. Furthermore, a putative transmembrane helix was identified at amino acid positions 89 to 109 of the long form of the deduced protein. Surprisingly, no transmembrane helix was found at this position in the corresponding protein of S. hygroscopicus.

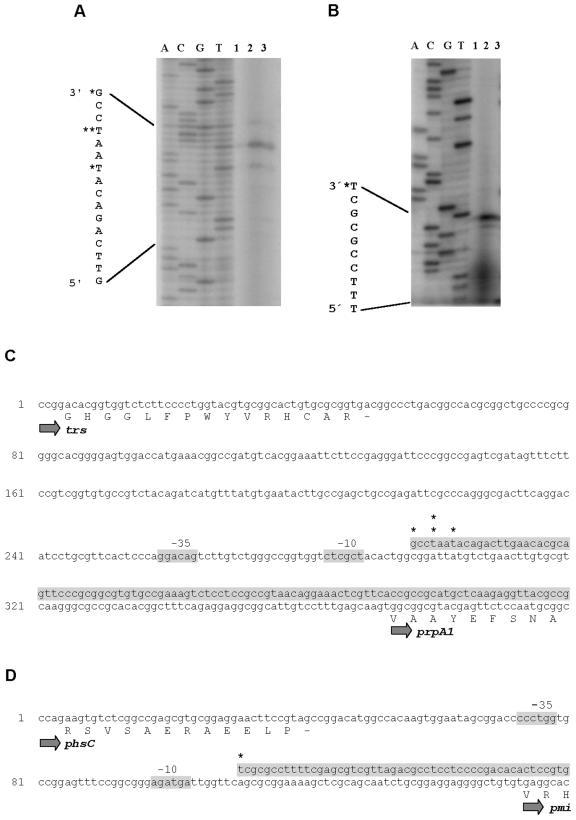

FIG. 5.

Mapping of pmi and prpA transcriptional start sites by a reverse transcription assay. RNAs were isolated from cells in different growth phases. Ppmi and PrpA1 were used as primers. The DNA transcript was characterized by running the samples alongside prpA (A) and pmi (B) sequencing reactions generated with the corresponding 32P-labeled primers. The sequences of the beginning of the transcripts and the transcriptional start sites (*) are presented. For the prpA transcripts, the positions of the minor (*) and major (**) signals are indicated. Lanes: 1, 24 h; 2, 48 h; and 3, 72 h. The corresponding promoter regions in prpA (C) and pmi (D) are shown. The −10 and −35 regions are marked. pmi, phosphinomethylmalate isomerase gene; phsC, phosphinothricin tripeptide synthetase C gene; trs, putative transporter gene; prpA1, phosphinothricin tripeptide biosynthesis regulatory gene (first start codon).

Identification of new PTT biosynthetic genes within the gene cluster.

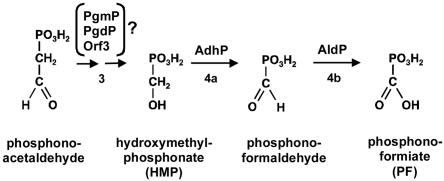

Five new genes—adhP, pgdP, orf3, pgmP, and aldP—were found in the previously unsequenced regions of the gene cluster. These genes were assumed to be PTT biosynthetic genes because of their location between PTT biosynthetic genes with proven functions. The deduced sequences of the AdhP and PgdP proteins are similar to sequences of alcohol dehydrogenases and d-3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenases, respectively. The orf3 gene product shows no similarity to any protein deposited in GenBank (Table 2). The deduced sequences of PgmP and AldP are similar to 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate-independent phosphoglycerate mutases and aldehyde dehydrogenases, respectively (Table 2). The functions of all of these proteins in the PTT biosynthetic pathway are unclear, but the gene products may be involved in the early oxidative steps 3 and 4, which have not yet been characterized (Fig. 2). Considering the similarity of PgmP and PdgP to enzymes of the glycolytic pathway, it is also possible that these enzymes are involved in providing the PTT biosynthetic precursors PEP and then acetyl-coenzyme A and l-alanine by transamination of pyruvate via primary metabolism. Genes encoding prephenate dehydrogenase and DHAP (3-deoxy-d-arabinose-7-heptulosonate-7-phosphate) synthase, enzymes of primary metabolism, have been found within the glycopeptide antibiotic biosynthetic gene clusters of various producers (8).

Involvement of the putative PTT secretion genes orfM and trs in PTT biosynthesis.

The mechanism of PTT secretion is unknown. In the PTT biosynthetic gene cluster, two genes (orfM and trs) were found that possibly encode proteins involved in this process.

OrfM is apparently a membrane protein with at least 13 predicted transmembrane helices (data not shown). In principle, the involvement of membrane proteins does not seem to be a common feature of antibiotic biosynthesis, with the exception of resistance mechanisms. Therefore, we investigated the role of orfM in PTT biosynthesis by mutational analysis. The gene was inactivated by replacing an internal 0.7-kb BlpI fragment with the aprP resistance cassette (Fig. 3) in the same direction of transcription as the following gene, phsC, to avoid polar effects. The resulting mutant did not produce PTT, which suggests an involvement of orfM in PTT biosynthesis, perhaps in secretion.

The Trs protein identified in the present study shows similarities to bacterial transport proteins (Table 2) and may therefore also be involved in the secretion of the antibiotic. If Trs is a PTT transporter, then its expression might confer resistance to PTT. To test this hypothesis, we cloned a 2.4-kb AatII/BamHI fragment carrying trs into the expression vector pEM4, resulting in plasmid pDS400, and introduced this plasmid by transformation into the PTT-sensitive strain S. lividans TK23. In this plasmid, trs is transcribed from the constitutive erythromycin resistance gene promoter (ermEp). Since the vector pEM4 has already been successfully used as an expression plasmid (11, 35) and since there is no termination structure between the AatII site and the trs gene, expression of the trs gene should take place. No difference in PTT sensitivity was detected between S. lividans TK23(pDS400) and the control strain S. lividans TK23(pEM4). Thus, Trs either is not involved in PTT secretion or functions only in a complex with other PTT biosynthetic proteins. Despite its location within the PTT biosynthetic gene cluster, it is also possible that trs has no function in PTT biosynthesis.

Gene disruption mutagenesis and overexpression of prpA.

The role of prpA in PTT biosynthesis was examined by gene disruption and by overexpression of the gene.

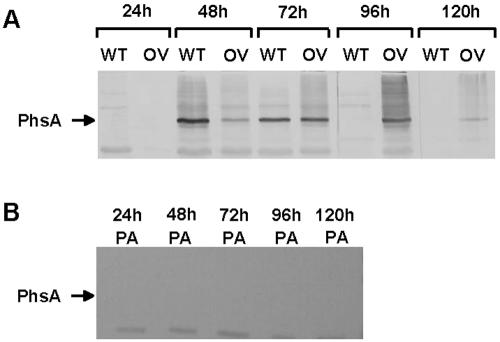

The inactivation of prpA resulted in a PTT-negative phenotype. As shown by Western blotting, PhsA, an essential PTT biosynthetic protein, was not synthesized in the mutant (Fig. 4B). This indicated that phsA and the other genes preceding phsA in the operon were not transcribed. Therefore, PrpA may be a transcriptional activator of PTT biosynthesis in S. viridochromogenes. The morphology of the prpA mutant was unchanged. This observation further strengthens the hypothesis that PrpA is a pathway-specific regulator since indirectly acting pleiotropic regulators usually affect both secondary metabolism and morphological differentiation.

FIG. 4.

Expression of phsA in wild-type (WT) S. viridochromogenes and a prpA overexpression strain (OV) (A) and in a prpA null mutant (PA) (B). In immunoblotting experiments using polyclonal antibodies raised against PhsA, the expression of the PTT biosynthetic gene phsA was examined at 24, 48, 72, 96, and 120 h. The location of the PhsA protein band is marked by an arrow.

The prpA gene was overexpressed by cloning downstream of the constitutive ermE promoter in the high-copy-number plasmid pEM4. This resulted in increased expression of phsA compared to the expression in the wild-type strain (Fig. 4A). The increased expression had no effect on the antibiotic yield after growth on yeast malt medium.

Determination of the transcriptional start sites of prpA and pmi.

In order to gain insights into the regulation of PTT biosynthesis in S. viridochromogenes, we determined the transcriptional start sites of the regulatory gene prpA and the putative PrpA-dependent PTT biosynthetic gene pmi. Promoter regions upstream of orf1 (35), pmi (11), and pat (38) have been identified in earlier studies by promoter probe analysis. The pmi promoter region, located on a 228-bp StuI/EcoRI DNA fragment, was chosen as an example of a region of DNA involved in the regulation of pmi and adjacent PTT biosynthetic genes according to the operon structure. The promoters of prpA and pmi were mapped by primer extension, using total RNAs isolated from cells in different growth phases. The transcriptional start site of the pmi gene was located 50 bp upstream of the putative translational start codon of pmi (Fig. 5B). The transcriptional start site of the prpA gene was located 192 bp upstream of the putative translational start codon of prpA (Fig. 5A). The corresponding −10 and −35 regions (Fig. 5) do not show significant similarities either to the Streptomyces promoter consensus sequences described by Bourn and Babb (5) or to each other.

One transcriptional start site for pmi was detected for all examined growth phases. In contrast, three transcriptional start sites for prpA, one major and two minor, were identified close to each other (Fig. 5). The prpA and pmi transcripts were detected at the first time point tested, after 24 h of incubation. The transcription of prpA was higher at 48 h and then lower again at 72 h, whereas the transcription level of pmi was similar at all of these time points.

DISCUSSION

In previous studies, several PTT (bialaphos) biosynthetic genes in S. viridochromogenes and S. hygroscopicus have been identified, but the genetic information needed for the elucidation of each biosynthetic step was lacking. For the present study, the remaining genes in the PTT biosynthetic gene cluster of S. viridochromogenes were characterized. The gene cluster consists of 24 genes on an approximately 33-kb DNA fragment. The deduced gene products of several biosynthetic genes showed high similarities (68 to 96% identities) to the corresponding proteins of the bialaphos producer S. hygroscopicus. The locations of these genes within the respective gene clusters (to date, approximately 16 kb of the S. hygroscopicus gene cluster has been described) are also very similar. Therefore, the overall genetic structures of the PTT biosynthetic gene clusters in the two organisms are probably identical. The genes involved in the formation of the PT precursor N-Ac-DMPT are found in the middle of the cluster. All biosynthetic genes responsible for the linkage of N-Ac-DMPT to other amino acids are located at the left and right boundaries. It would be interesting to compare the genetic organization of the PTT biosynthetic gene cluster to the genetic organization of genes involved in the synthesis of other compounds containing PT and an amino acid other than alanine, e.g., trialaphos (phosphinothricyl-alanyl-alanyl-alanine) from S. hygroscopicus KSB1285 (17) and phosalacine (phosphinothricyl-alanyl-leucine) from Kitasatospora phosalacinea (26). However, no such genetic data are available.

The gene product of prpA was shown to be involved in the regulation of PTT biosynthetic genes by the loss of PTT production and the lack of phsA expression in a prpA mutant. In contrast to actinorhodin production in S. coelicolor (9) and monensin production in Streptomyces cinnamonensis (25), PTT production in S. viridochromogenes was not significantly affected by overexpression of the pathway-specific regulatory gene; the overexpression of prpA seemed only to increase the expression of PTT biosynthetic genes.

The PrpA protein is similar to response regulators of two-component systems and is characterized by a DNA-binding domain in the C-terminal region of the protein. However, a receiver domain with a putative phosphorylation site was not found at the N-terminal end. Only several hydrophobic sites and a putative transmembrane helix were found in this region; these structures are probably involved in recognition and activation by an unknown receptor or activator protein or in membrane interactions. Interestingly, PrpA and the corresponding protein from S. hygroscopicus (BrpA) differ in this region. In addition to differences at the protein level, which are also indicated by the relatively low similarity value of 58%, the regulation of the corresponding genes seems to be different. The intergenic regions preceding prpA and brpA differ in size (322 and 442 bp for prpA in S. viridochromogenes and 304 bp for brpA in S. hygroscopicus), and the identified prpA promoter region shows no similarity to the corresponding region of the brpA gene. Furthermore, three different transcriptional start points are found in S. hygroscopicus (28), whereas only one was identified in S. viridochromogenes. The results also mirror the difference in regulation described by Tabakov et al. (39), who showed that the initiation of brpA transcription in S. hygroscopicus is mediated by the pleiotropically acting transcriptional regulator BrpB, which is encoded by a gene located outside of the bialaphos biosynthetic gene cluster. For S. viridochromogenes, no brpB homologue has been found (39), and the binding sites of BrpB are also lacking (39). Thus, an unknown regulator is involved in the activation of transcription of prpA.

Despite many reports on PTT (bialaphos) biosynthesis, the mechanisms of several biosynthetic steps, e.g., the conversion of phosphonoacetaldehyde to hydroxymethylphosphonic acid (HMP) in step 3 and the subsequent oxidation of HMP to phosphonoformiate (probably via phosphonoformaldehyde) in step 4 (Fig. 2), are still unclear. The information on the complete biosynthetic gene cluster, including genes that were thus far undescribed, now provides an opportunity to define possible reaction schemes. For example, it seems likely that the putative alcohol dehydrogenase AdhP and the aldehyde dehydrogenase AldP are involved in the oxidation of HMP via phosphonoformaldehyde to phosphonoformiate in step 4 (Fig. 6). In step 3, the formation of HMP, a Bayer-Villiger oxidation, by the incorporation of molecular oxygen and subsequent hydrolysis was postulated (H. Seto, personal communication). However, no gene was found within the PTT biosynthetic gene cluster that encodes a Bayer-Villiger oxidase, which usually catalyzes such a reaction. A protein encoded by the newly identified gene pgmP, pgdP, or orf3 might be involved in this process. Further molecular genetic and biochemical studies are necessary to verify this hypothesis.

FIG. 6.

Postulated reaction for the formation of phosphonoformiate from phosphonoacetaldehyde in the PTT biosynthetic pathway.

The putative function of orfM in PTT biosynthesis is also interesting. orfM is probably a part of a transcriptional unit containing orf1, phsB, and phsC, and it is also translationally coupled to phsB. Since translational coupling is a characteristic of many bacterial genes whose products are required in equimolar quantities (24), a functional interaction between the products of these genes may occur. The deduced orfM gene product shows the typical features of a membrane protein. However, according to the postulated biosynthetic pathway (41) (Fig. 2), a membrane protein would only be involved in the last step, the export of the antibiotic. Approximately 4 kb downstream of the peptide synthetase-encoding gene phsA, an ORF (trs) was identified whose deduced gene product resembles a citrate-proton symporter from E. coli. The role of this protein in PTT export in S. hygroscopicus has been discussed but not experimentally proven (28). Since the corresponding S. viridochromogenes protein does not confer PTT resistance by antibiotic transport (this study), Trs may require another membrane protein (such as OrfM) to exert its action. Another possibility is that OrfM is a membrane anchor for a biosynthetic protein complex, possibly containing PhsB and the other enzymes of the nonribosomal peptide synthesis machinery. However, to date, there is no indication of a membrane-anchored peptide synthetase complex for nonribosomal peptide synthesis in other organisms.

In the postulated biosynthetic pathway of PTT (Fig. 2), there are still two reactions for which genes have not been identified within the cluster, i.e., step 8, the formation of deamino-α-ketodemethylphosphinothricin (DKDPT) by an isocitrate dehydrogenase-like reaction, and step 9, the conversion of DKDPT to demethylphosphinothricin. According to Thompson and Seto (41), these reactions might be carried out by the corresponding enzyme of the tricarboxylic acid cycle and a ubiquitous aminotransferase of the primary metabolism, respectively.

The ends of the PTT biosynthetic gene cluster were defined by the inactivation of flanking genes that showed no effect on antibiotic production. Interestingly, a mutant of the orfB2 gene, which is located at the left boundary of the PTT biosynthetic gene cluster, was characterized by a bald phenotype. This points to a possible role of this gene, perhaps together with the neighboring gene orfB1, in the morphological differentiation of streptomycetes.

The morphological differentiation of streptomycetes is a complicated network. Despite the identification of a large number of different bald genes (bld), which are involved in aerial mycelium formation, and white genes (whi), which function in spore formation, possibly many unidentified genes and proteins with conserved functions in all Streptomyces species also play a role in this process. For example, the deduced proteins of orfB1 and orfB2 have no sequence similarity to known proteins, but the encoding genes are conserved in streptomycetes whose genome sequences have been determined, and the gene arrangement is identical in S. viridochromogenes, Streptomyces avermitilis, and S. coelicolor. Therefore, the two genes appear to be new differentiation factors of streptomycetes.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the DFG (Graduiertenkolleg “Mikrobiologie” and SPP1152) and the BMBF (GenoMik Network).

We thank Karen Brune for a critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alijah, R., J. Dorendorf, S. Talay, A. Pühler, and W. Wohlleben. 1991. Genetic analysis of the phosphinothricin-tripeptide biosynthetic pathway of Streptomyces viridochromogenes Tü 494. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 34:749-755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul, S. F., W. Gish, W. Miller, E. W. Myers, and D. J. Lipman. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bayer, E., K. H. Gugel, K. Hägele, H. Hagenmaier, S. Jassipow, W. A. König, and H. Zähner. 1972. Stoffwechselprodukte von Mikroorganismen. Phosphinothricin und Phosphinothricyl-Alanyl-Alanin. Helv. Chim. Acta 55:224-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bibb, M. J., P. R. Findlay, and M. W. Johnson. 1984. The relationship between base composition and codon usage in bacterial genes and its use for the simple and reliable identification of protein-coding sequences. Gene 30:157-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bourn, W. R., and B. Babb. 1995. Computer assisted identification and classification of streptomycete promoters. Nucleic Acids Res. 23:3696-3703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bullock, W. O., J. M. Fernandez, and J. M. Short. 1987. Xl1-Blue, a high efficiency plasmid transforming recA Escherichia coli strain with beta galactosidase selection. Focus 5:376-378. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cserzo, M., E. Wallin, I. Simon, G. von Heijne, and A. Elofsson. 1997. Prediction of transmembrane alpha-helices in procaryotic membrane proteins: the dense alignment surface method. Protein Eng. 10:673-676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donadio, S., M. Sosio, E. Stegmann, T. Weber, and W. Wohlleben. Comparative analysis and insights into the evolution of gene clusters for glycopeptide antibiotic biosynthesis. Submitted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Fernández-Moreno, M. A., J. L. Caballero, D. A. Hopwood, and F. Malpartida. 1991. The act cluster contains regulatory and antibiotic export genes, direct targets for translational control by the bldA tRNA gene of Streptomyces. Cell 66:769-780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grammel, N., D. Schwartz, W. Wohlleben, and U. Keller. 1998. Phosphinothricin-tripeptide synthetases from Streptomyces viridochromogenes. Biochemistry 37:1596-1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heinzelmann, E., G. Kienzlen, S. Kaspar, J. Recktenwald, W. Wohlleben, and D. Schwartz. 2001. The phosphinomethylmalate isomerase gene pmi, encoding an aconitase-like enzyme, is involved in the synthesis of phosphinothricin tripeptide in Streptomyces viridochromogenes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:3603-3609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hidaka, T., M. Hidaka, T. Uozumi, and H. Seto. 1992. Nucleotide sequence of a carboxyphosphoenolpyruvate phosphonomutase gene isolated from a bialaphos-producing organism, Streptomyces hygroscopicus, and its expression in Streptomyces lividans. Mol. Gen. Genet. 233:476-478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hidaka, T., K. W. Shimothono, T. Morishita, and H. Seto. 1999. Studies on the biosynthesis of bialaphos (SF-1293). 18. 2-Phosphinomethylmalic acid synthase: a descendant of (R)-citrate synthase? J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 52:925-931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hofman, K., and W. Stoffel. 1993. TMBase—a database of membrane spanning protein segments. Biol. Chem. Hoppe-Seyler 374:166. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hopwood, D. A., M. J. Bibb, K. F. Chater, T. Kieser, C. J. Bruton, H. M. Kieser, D. J. Lydiate, C. P. Smith, J. M. Ward, and H. Schrempf. 1985. Genetic manipulation of Streptomyces: a laboratory manual. John Innes Foundation, Norwich, Conn.

- 16.Kamigiri, K., T. Hidaka, S. Imai, T. Murakami, and H. Seto. 1991. Studies on the biosynthesis of bialaphos (SF-1293). 12. C-P bond formation mechanism of bialaphos: discovery of a P-methylation enzyme. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 45:781-787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kato, H., K. Nagayama, H. Abe, R. Kobayashi, and E. Ishihara. 1991. Isolation, structure and biological activity of trialaphos. Agric. Biol. Chem. 55:1133-1134. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kieser, T., M. J. Bibb, M. J. Buttner, K. F. Chater, and D. A. Hopwood. 2000. Practical Streptomyces genetics. John Innes Foundation, Norwich, United Kingdom.

- 19.Kondo, Y., T. Shomura, Y. Ogawa, T. Tsuruoka, H. Watanabe, K. Totsukawa, T. Suzuki, C. Moriyama, J. Yoshida, S. Inouye, and T. Niida. 1973. Studies on a new antibiotic SF-1293. I. Isolation and physico-chemical and biological characterization of SF-1293 substances. Sci. Rep. Meiji Seika 13:34-41. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee, S.-H., T. Hidaka, H. Nakashita, and H. Seto. 1995. The carboxyphosphoenolpyruvate synthase-encoding gene from the bialaphos-producing organism Streptomyces hygroscopicus. Gene 153:143-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muschko, K., G. Kienzlen, H.-P. Fiedler, W. Wohlleben, and D. Schwartz. 2002. Tricarboxylic acid cycle aconitase activity during the life cycle of Streptomyces viridochromogenes Tü494. Arch. Microbiol. 178:499-505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muth, G., B. Nussbaumer, W. Wohlleben, and A. Pühler. 1989. A vector system with temperature-sensitive replication for gene disruption and mutational cloning in streptomycetes. Mol. Gen. Genet. 219:341-348. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nicholas, K. B., H. B. Nicholas, Jr., and D. W. Deerfield II. 1997. GeneDoc: analysis and visualization of genetic variation. EMBNEW.NEWS 4:14. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Normark, S., S. Bergström, T. Edlund, T. Grundström, B. Jaurin, F. P. Lindberg, and O. Olsson. 1983. Overlapping genes. Annu. Rev. Genet. 17:499-525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oliynyk, M., C. B. Stark, A. Bhatt, M. A. Jones, Z. A. Hughes-Thomas, C. Wilkinson, Z. Oliynyk, Y. Demydchuk, J. Staunton, and P. F. Leadlay. 2003. Analysis of the biosynthetic gene cluster for the polyether antibiotic monensin in Streptomyces cinnamonensis and evidence for the role of monB and monC in oxidative cyclization. Mol. Microbiol. 49:1179-1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Omura, S., K. Hinotozawa, N. Imamura, and M. Murata. 1984. The structure of phoasalacine, a new antibiotic containing phosphinothricin. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 37:939-940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quiros, L. M., I. Aguirrezabalaga, C. Olano, C. Mendez, and J. A. Salas. 1998. Two glycosyltransferases and a glycosidase are involved in oleandomycin modification during its biosynthesis by Streptomyces antibioticus. Mol. Microbiol. 28:1177-1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raibaud, A., M. Zalacain, T. G. Holt, R. Tizard, and C. J. Thompson. 1991. Nucleotide sequence analysis reveals linked N-acetyl hydrolase, thioesterase, transport, and regulatory genes encoded by the bialaphos biosynthetic gene cluster of Streptomyces hygroscopicus. J. Bacteriol. 173:4454-4463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Richardson, M. A., S. Kuhstoss, P. Solenberg, N. A. Schaus, and R. N. Rao. 1987. A new shuttle cosmid vector, pKC505, for streptomycetes: its use in the cloning of three different spiramycin resistance genes from a Streptomyces ambofaciens library. Gene 61:231-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rutherford, K., J. Parkhill, J. Crook, T. Horsnell, P. Rice, M.-A. Rajandream, and B. Barrell. 2000. Artemis: sequence visualisation and annotation. Bioinformatics 16:944-945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sambrook, J., T. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 32.Sanger, F., S. Nicklen, and A. R. Coulson. 1977. DNA sequencing with chain terminating inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 74:5463-5467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schwartz, D., R. Alijah, B. Nussbaumer, S. Pelzer, and W. Wohlleben. 1996. The peptide synthetase gene phsA from Streptomyces viridochromogenes is not juxtaposed with other genes involved in nonribosomal biosynthesis of peptides. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:570-577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schwartz, D., J. Recktenwald, S. Pelzer, and W. Wohlleben. 1998. Isolation and characterization of the PEP-phosphomutase and the phosphonopyruvate decarboxylase genes from the phosphinothricin tripeptide producer Streptomyces viridochromogenes Tü494. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 163:149-157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schwartz, D., N. Grammel, U. Keller, and W. Wohlleben. Phosphinothricin tripeptide assembly in Streptomyces viridochromogenes Tü494. Submitted for publication.

- 36.Schwarzer, D., H. D. Mootz, U. Linne, and M. A. Marahiel. 2002. Regeneration of misprimed nonribosomal peptide synthetases by type II thioesterases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:14083-14088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Staden, R., and A. D. McLachlan. 1982. Codon preference and its use in identifying protein coding regions in large DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 10:141-156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Strauch, E., W. Wohlleben, and A. Pühler. 1988. Cloning of a phosphinothricin N-acetyltransferase gene from Streptomyces viridochromogenes Tü494 and its expression in Streptomyces lividans and Escherichia coli. Gene 63:65-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tabakov, V., and T. A. Voeikova. 1997. Elements of regulatory systems of antibiotic biosynthesis in Streptomyces. Genetica 33:1461-1477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tesch, C., K. Nikoleit, V. Gnau, F. Götz, and C. Bormann. 1996. Biochemical and molecular characterization of the extracellular esterase from Streptomyces diastatochromogenes. J. Bacteriol. 178:1858-1865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thompson, C. J., and H. Seto. 1995. Bialaphos, p. 197-222. In L. C. Vining and C. Stuttard (ed.), Genetics and biochemistry of antibiotic production. Butterworth Heinemann Biotechnology, Oxford, United Kingdom.

- 42.Thompson, J. D., D. G. Higgins, and T. J. Gibson. 1994. ClustalW: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:4673-4680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wohlleben, W., W. Arnold, I. Broer, D. Hillemann, E. Strauch, and A. Pühler. 1988. Nucleotide sequence of the phosphinothricin N-acetyltransferase gene from Streptomyces viridochromogenes Tü494 and its expression in Nicotiana tabacum. Gene 70:25-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wohlleben, W., R. Alijah, J. Dorendorf, D. Hillemann, B. Nussbaumer, and S. Pelzer. 1992. Identification and characterization of phosphinothricin-tripeptide biosynthetic genes in Streptomyces viridochromogenes. Gene 115:127-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]