Abstract

An oligonucleotide primer, NITRO821R, targeting the 16S rRNA gene of unicellular cyanobacterial N2 fixers was developed based on newly derived sequences from Crocosphaera sp. strain WH 8501 and Cyanothece sp. strains WH 8902 and WH 8904 as well as several previously described sequences of Cyanothece sp. and sequences of intracellular cyanobacterial symbionts of the marine diatom Climacodium frauenfeldianum. This oligonucleotide is specific for the targeted organisms, which represent a well-defined phylogenetic lineage, and can detect as few as 50 cells in a standard PCR when it is used as a reverse primer together with the cyanobacterium- and plastid-specific forward primer CYA359F (U. Nübel, F. Garcia-Pichel, and G. Muyzer, Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:3327-3332, 1997). Use of this primer pair in the PCR allowed analysis of the distribution of marine unicellular cyanobacterial diazotrophs along a transect following the 67°E meridian from Victoria, Seychelles, to Muscat, Oman (0.5°S to 26°N) in the Arabian Sea. These organisms were found to be preferentially located in warm (>29°C) oligotrophic subsurface waters between 0 and 7°N, but they were also found at a station north of Oman at 26°N, 56°35′E, where similar water column conditions prevailed. Slightly cooler oligotrophic waters (<29°C) did not contain these organisms or the numbers were considerably reduced, suggesting that temperature is a key factor in dictating the abundance of this unicellular cyanobacterial diazotroph lineage in marine environments.

Microbial N2 fixation has traditionally been considered to be of minor importance as a source of fixed nitrogen in oceanic environments (5). Contemporary mass balance estimates, however, have suggested that there is excess removal of combined forms of nitrogen, particularly from areas of the tropical ocean, and it has been proposed that biological N2 fixation may account for the imbalances (6, 12). This has led to a radically revised view of the quantitative importance of this process in the nitrogen cycle. Current estimates of global N2 fixation are ∼240 Tg of N year−1 and a marine contribution of ∼80 Tg of N year−1 (4). Trichodesmium, a filamentous nonheterocystous cyanobacterium broadly distributed throughout tropical and subtropical oceans, has long been considered to be responsible for most of this marine N2 fixation (see references 3 and 17 for recent reviews). However, recently, Zehr et al. (34) showed that unicellular cyanobacteria that are 3 to 10 μm in diameter may make a significant contribution to oceanic N2 fixation. Indeed, based on N2 fixation data for the 0.2- to 10-μm bacterioplankton size fraction and the concentrations of phycoerythrin-containing unicellular cyanobacteria, they estimated that this contribution might equal or exceed that of Trichodesmium.

Several unicellular marine cyanobacterial diazotrophs belonging to the genera Synechococcus (15, 16) Cyanothece (21), and Crocosphaera (28) have previously been described. These organisms all have temporal separation of N2 fixation and photosynthesis, which is likely controlled by an endogenous circadian rhythm (22). In addition to these free-living isolates, 16S rRNA gene (rDNA) sequences derived from cyanobacterial symbionts of the marine diatom Climacodium fraeuenfeldianum show close phylogenetic relatedness, suggesting that unicellular cyanobacterial symbionts also have the potential to contribute to N2 fixation (7, 9, 10). Although several studies have now reported the presence of unicellular phycoerythrin-containing cyanobacteria that are 3 to 10 μm in diameter in geographically separated marine environments (2, 18, 27), suggesting that there is widespread distribution, the exact contribution of these unicellular cyanobacterial strains to global N2 fixation rates remains to be determined. Indeed, a means to specifically detect or analyze the diversity of these organisms is not yet available. To address this problem, we developed a 16S rDNA oligonucleotide primer that specifically recognizes the discrete marine unicellular cyanobacterial diazotroph lineage within which nearly all previously documented isolates lie. We also describe the utility of this oligonucleotide as a PCR primer for assessing the distribution of these organisms along a transect in the Arabian Sea situated in the northwest Indian Ocean.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

PCR amplification.

16S rDNA sequences were amplified from Cyanothece sp. strains WH 8902 and WH 8904 and Crocosphaera sp. strain WH 8501 (29) by using the PCR primers OXY107F and OXY1313R (Table 1, 31) and conditions described previously (30) and cloned into the TA vector pCR2.1-TOPO (Invitrogen). Cyanobacterial 16S rDNA clones were identified from heterotrophic contaminants of the culture by PCR screening by using PCR primers CYA359F and OXY1313R (Table 1) prior to sequencing.

TABLE 1.

PCR primers used in this study

| Primer | Target | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| NITRO821R | 16S rDNA of unicellular cyanobacterial diazotrophs | CAA GCC ACA CCT AGT TTC | This study |

| CYA359F | 16S rDNA of cyanobacteria | GGG GAA TYT TCC GCA ATG GG | 19 |

| OXY107F | 16S rDNA of oxygenic phototrophs biased | GGA CGG GTG AGT AAC GCG GTG | 31 |

| OXY1313R | 16S rDNA of oxygenic phototrophs biased | CTT CAY GYA GGC GAG TTG CAG C | 31 |

| CNF | nifH of cyanobacteria biased | CGT AGG TTG CGA CCC TAA GGC TGA | 20 |

| CNR | nifH of cyanobacteria biased | GCA TAC ATC GCC ATC ATT TCA CC | 20 |

DNA sequencing.

PCR products and double-stranded plasmid DNAs were sequenced bidirectionally by using an ABI 373A automated sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) at the Warwick University sequencing facility.

Phylogenetic analysis and development of the NITRO821R primer.

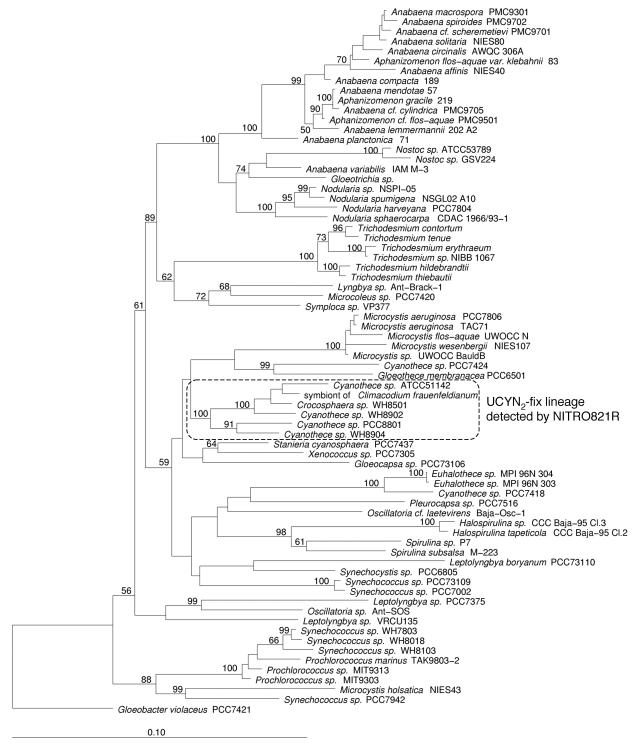

16S rDNA sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis were performed by using the ARB software (13). The NITRO821R oligonucleotide primer (Table 1) was designed to specifically recognize the phylogenetic lineage in which the unicellular cyanobacterial diazotrophs Cyanothece sp. strains WH 8902, WH 8904, and PCC8801 (also known as Synechococcus sp. strain RF-1 [25]) and Crocosphaera sp. strain WH 8501 lie (Fig. 1) by using the probe design and probe match tools from the ARB program.

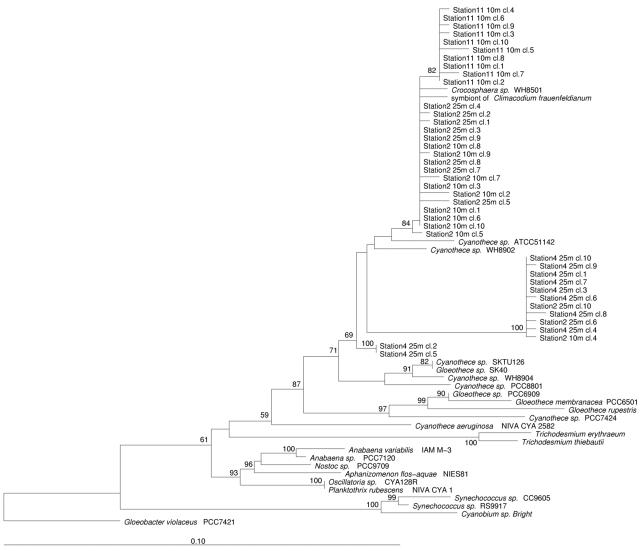

FIG. 1.

Phylogenetic tree showing the relationships of marine and freshwater cyanobacteria, including diazotrophs and nondiazotrophs, inferred from 16S rDNA sequences. The tree was constructed by the neighbor-joining method with Jukes-Cantor correction. The percentages of bootstrap replicates supporting the branching order are indicated at the nodes. Partial sequences (<1,190 nucleotides) were added to the tree by using a maximum-parsimony option within ARB. The cyanobacterium Gloeobacter violaceus PCC7421 was used as a root. The scale bar represents the equivalent of 0.1 substitution per nucleotide.

Genomic DNA isolation.

Genomic DNA was isolated from Trichodesmium sp. strain WH 9601, Synechococcus sp. strain CC9605, Prochlorococcus sp. strains EQPAC1 (HLI lineage), TAK9803-2 (HLII lineage), and MIT9313 (LL lineage), Planktothrix rubescens strain 97112, Anabaena variabilis, Anabaena sp. strain PCC7118, Nostoc sp. strain PCC7120, Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803, Microcystis sp. strain PCC7806, and Gloeotrichia sp. for use in the PCR to determine the specificity of the NITRO821R primer described above by using a previously described protocol (11).

Sampling.

Water samples for DNA extraction were collected during the NERC-funded AMBITION cruise in the Arabian Sea from 1 to 27 September 2001 aboard the RRS Charles Darwin. Samples were obtained from discrete depths at 11 stations along a 5,500-km transect (Table 2 and Fig. 2) between Victoria, Seychelles, and Muscat, Oman, by using 20-liter Niskin bottles on a hydrographic cable. Conductivity, temperature, and barometric pressure were measured simultaneously with a CTD (model Sea-Bird 9/11). Seawater (5 to 10 liters) from each depth was filtered onto 47-mm-diameter, 0.45-μm-pore-size polysulfone filters (Supor-450; Gelman Sciences Inc., Ann Arbor, Mich.) after prefiltration through a 47-mm-diameter, 3-μm-pore-size filter (MCE MF-Millipore filters [Fisher]) with a gentle vacuum (10 mm of Hg). This allowed collection of >3- and 3- to 0.45-μm fractions. The filters were placed in a 5-ml cryovial with 3 ml of DNA lysis buffer (0.75 M sucrose, 400 mM NaCl, 20 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris HCl [pH 9.0]) and stored at −80°C until extraction.

TABLE 2.

Positions of the principal stations along the AMBITION cruise transect

| Station | Latitude | Longitude |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 00°55′S | 64°08′E |

| 2 | 00°00′N | 67°00′E |

| 3 | 03°48′N | 67°00′E |

| 4 | 07°36′N | 67°00′E |

| 5 | 11°24′N | 67°00′E |

| 6 | 15°12′N | 67°00′E |

| 7 | 19°00′N | 67°00′E |

| 8 | 20°55′N | 64°00′E |

| 9 | 22°40′N | 60°41′E |

| 10 | 23°55′N | 59°15′E |

| 11 | 26°00′N | 56°35′E |

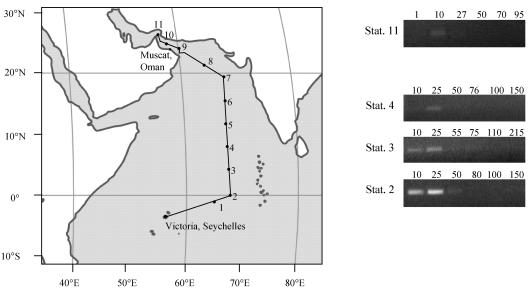

FIG. 2.

Distribution of the UCYN2-fix lineage along the AMBITION cruise transect in the Arabian Sea. The sampling stations are indicated by dots and are numbered in the order of sampling. Representative agarose gels for stations giving detectable PCR products with the CYA359F-NITRO821R primer pair are shown on the right. The numbers above the lanes indicate the depth of sampling (in meters). Sta., station.

Environmental DNA isolation.

DNA was extracted from the filters in lysis buffer as described by Fuller et al. (11).

Development of the dual analytical PCR.

For specific amplification of the 16S rDNA of marine unicellular cyanobacterial diazotrophs, the specific NITRO821R primer was used in conjunction with the cyanobacterium- and plastid-specific forward primer CYA359F (19) (Table 1). For amplification of environmental nifH sequences we used the cyanobacterium-biased primer pair described by Olson et al. (20), which we designated CNF-CNR (Table 1). PCRs were carried out in 25-μl mixtures containing 0.5 μl of template (cells or environmental DNA sample), each deoxynucleoside triphosphate at a concentration of 200 μM, 2 mM MgCl2, each primer at a concentration of 0.2 μM (for 16S rDNA amplification) or 1 μM (for nifH amplification), and 0.625 U of Taq polymerase in 1× enzyme buffer (GIBCO BRL, Life Technologies Ltd., Paisley, Scotland). For amplification of environmental DNA we also included 1 mg of bovine serum albumin (Sigma) ml−1. The amplification conditions comprised a denaturation step of 95°C for 5 min and then 80°C for 1 min, at which time Taq polymerase was added, followed by 30 cycles of 95°C for 1 min, 57°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 40 s and a final extension of 6 min at 72°C. Reaction mixtures were stored at 4°C prior to analysis. Products (10 of 25 μl) were resolved by gel electrophoresis on a 1.5% (wt/vol) agarose gel at 100 V. DNA was stained with ethidium bromide (0.5 μg ml−1), visualized under short-wavelength UV, and photographed with a gel documentation system (UVP Inc., Upland, Calif.).

Relative quantification of PCR products.

Ethidium bromide-stained agarose gels were quantified by using the array analysis tool in the TotalLab software (Nonlinear Dynamics).

Clone libraries.

Eight clone libraries were constructed, four each for nifH and 16S rDNA, by using the CNF-CNR and CYA359F-NITRO821R primers, respectively. The libraries were constructed by using environmental DNA from the AMBITION cruise transect obtained at station 2 (depth, 10 and 25 m), station 4 (depth, 25 m), and station 11 (depth, 10 m). PCR products from each depth were ligated into the pCR2.1-TOPO cloning vector before transformation into Escherichia coli strain TOP10F (Invitrogen Corporation, San Diego, Calif.). Plasmid DNA was isolated from transformants with a QIAprep miniprep kit (QIAGEN Ltd., Crawley, West Sussex, United Kingdom). Ten clones were subsequently sequenced from each library prior to phylogenetic analysis by using the ARB software as described above.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

16S rDNA and nifH sequences reported in this paper have been deposited in the GenBank database under accession numbers AY620237 to AY620241 (cultured strains) and AY621666 to AY621747 (AMBITION cruise environmental sequences).

RESULTS

NITRO821R primer design, specificity, and sensitivity.

The 16S rRNA sequences obtained for Cyanothece sp. strains WH 8904 and WH 8902 and Crocosphaera sp. strain WH 8501 were compared with other sequences from the cyanobacterial radiation, and the results are shown as a phylogenetic tree in Fig. 1. Cyanothece sp. strain WH 8902 is more closely related to Crocosphaera sp. strain WH 8501 (97.1% identity) than to Cyanothece sp. strain WH 8904 (94.8% identity), but all three strains form a coherent lineage that is well supported phylogenetically and also contains other marine unicellular cyanobacterial diazotrophs, including 16S rDNA sequences from cyanobacterial symbionts of the diatom C. frauenfeldianum. Within this lineage Cyanothece sp. strains ATCC 51142 and PCC8801 (= Synechococcus sp. strain RF-1 [25]) show the greatest diversity (93.2% identity). Alignment of the 16S rDNA sequences of all members of this unicellular cyanobacterial diazotroph lineage (designated the UCYN2-fix lineage) and comparison with all other cyanobacterial and environmental DNA sequences in the databases allowed the design of an oligonucleotide primer, NITRO821R (Table 1), that showed complete identity to sequences of all members of this UCYN2-fix lineage. In silico alignments showed that members of the genus Planktothrix have a 1-bp mismatch with this oligonucleotide. Otherwise, the most closely related 16S rDNA sequences had at least two mismatches with the NITRO821R primer (Table 3), while BLAST searches (1) did not reveal any significant homology with other eubacterial or archaeal 16S rDNA sequences.

TABLE 3.

Specificity of the NITRO821R oligonucleotide illustrated, by alignment of the primer and target sequences with the 16S rDNA sequences of different marine unicellular diazotrophs and other cyanobacteria

| Probe, target, or organism | Sequencea |

|---|---|

| Probe NITRO821R | 3′-CTT TGA TCC ACA CCG AAC-5′ |

| Target | 5′-GAA ACT AGG TGT GGC TTG-3′ |

| Crocosphaera sp. strain WH 8501 | ... ... ... ... ... ... |

| Cyanothece sp. strain WH 8902 | ... ... ... ... ... ... |

| Cyanothece sp. strain WH 8904 | ... ... ... ... ... ... |

| Planktothrix rubescens 97112 | ... ... ... ... ... C.. |

| Anabaena variabilis | ..T ... ... C.. ... ... |

| Anabaena sp. strain PCC7118 | ..T ... ... C.. ... ... |

| Gloeotrichia sp. | ..T ... ... C.. ... ... |

| Nostoc sp. strain PCC7120 | ..T ... ... C.. ... ... |

| Microcystis sp. strain PCC7806 | ..T ... ... C.. ... ... |

| Trichodesmium erythraeum/T. thiebautii | ..T ... ... ... T.. C... |

| Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803 | ..T ... ... ... T.T C.. |

| Synechococcus sp. strain CC9605 | A.C ... ... ... C.G GG. |

| Prochlorococcus sp. strain EQPAC1 (- HLI) | A.C ... ... ... C.G GG. |

| Prochlorococcus sp. strain TAK9803-2 (- HLII) | A.C ... ... ... C.G GG. |

| Prochlorococcus sp. strain MIT9313 (- LL) | A.C ... ... ... C.G GG. |

Dots indicate bases identical to those of the target sequence.

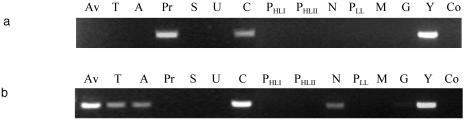

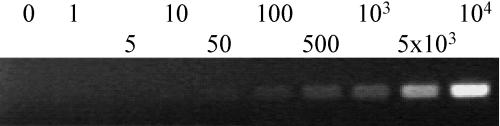

The NITRO821R primer was subsequently used as a reverse primer in PCRs together with the cyanobacterium- and plastid-specific forward primer CYA359F (19). Our searches with the sequences in the currently available bacterial 16S rDNA databases, including the new sequences for Cyanothece sp. and Crocosphaera sp. reported here, confirm the specificity of CYA359F for recognizing all cyanobacterial 16S rDNA sequences, as previously reported (19). By using genomic DNAs extracted from a range of cyanobacterial genera, including the commonly found marine genera Synechococcus, Prochlorococcus, and Trichodesmium, as templates, the specificity of the primer pair in the PCR for the UCYN2-fix lineage was determined (Fig. 3A). As expected, sequences of all members of the UCYN2-fix lineage tested were amplified. In addition, however, the sequence of P. rubescens, a representative of the genus Planktothrix, was also amplified with this primer pair. This filamentous cyanobacterial genus is, however, restricted to freshwater environments. The sequences of all other marine and freshwater cyanobacteria with two or more mismatches in the 16S rDNA sequence compared with the NITRO821R primer sequence were not amplified. A similar use of the CNF-CNR primer pair for detecting only cyanobacterial diazotrophs was also confirmed (Fig. 3B). Subsequently, by using a dilution series of Cyanothece sp. strain WH 8902 cells, the detection limit of the analytical PCR with the CYA359F-NITRO821R primer pair was determined to be as low as 50 cells per PCR under the conditions used (Fig. 4). This combination of specificity and sensitivity suggested that the CYA359F-NITRO821R primer combination should be an extremely useful tool for specific, semiquantitative detection of unicellular cyanobacterial diazotrophs in natural marine samples.

FIG. 3.

Specificity of amplification with 16S rDNA primers CYA359F and NITRO821R (a) or nifH primers CNF and CNR (20) (b). Lane Av, Anabaena variabilis; lane T, Trichodesmium sp. strain WH 9601; lane A, Anabaena sp. strain PCC7118; lane Pr, Planktothrix rubescens; lane S, Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803; lane U, Synechococcus sp. strain CC9605; lane Y, Cyanothece sp. strain WH 8902; lane C, Cyanothece sp. strain WH 8904; lane PHLI, Prochlorococcus sp. strain EQPAC1; lane PHLII, Prochlorococcus sp. strain TAK9803-2; lane PLL, Prochlorococcus sp. strain MIT9313; lane N, Nostoc sp. strain PCC7120; lane M, Microcystis sp. strain PCC7806; lane G, Gloeotrichia sp.; lane Co, control (no DNA).

FIG. 4.

Limit of detection of the CYA359F-NITRO821R PCR. The numbers of Cyanothece sp. strain WH 8902 cells in the 25-μl reaction mixtures are indicated at the top.

Distribution and abundance of members of the UCYN2-fix lineage in the Arabian Sea.

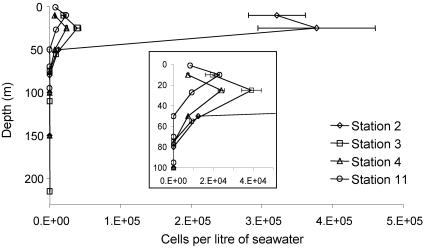

Environmental DNAs extracted from the >3-μm fraction in depth profiles along the AMBITION cruise transect (Table 2 and Fig. 2) were used as the templates in PCRs with the CYA359F-NITRO821R primer pair. The results showed that the UCYN2-fix lineage was present only in subsurface waters at stations 2, 3, 4, and 11; the peak abundance occurred at a depth of around 25 m, and the lineage was undetectable at depths greater than 50 m (Fig. 2). Semiquantitative analysis of these data by using the Cyanothece sp. strain WH 8902 standard curve allowed relative cell abundance estimates to be made (Fig. 5). This analysis showed that the peak estimated levels were 3.8 × 105 ± 8 × 104 cells per liter (mean ± standard error) at a depth of 25 m at station 2, and lower numbers (around 2.4 × 104 ± 1.6 × 103 to 4 × 104 ± 4.9 × 103 cells per liter) were obtained at stations 3, 4, and 11. The UCYN2-fix lineage was either absent or undetectable at all other stations along the transect.

FIG. 5.

Relative abundance of the UCYN2-fix lineage along the AMBITION cruise transect in the Arabian Sea. The error bars indicate standard errors. The inset shows the data for stations 3, 4, and 11 in more detail.

The distribution of cyanobacterial diazotrophs in the >3-μm fraction along the AMBITION cruise transect was also investigated by using the nifH-specific primers CNF and CNR. PCR products were obtained from stations 1 and 4 and at station 11; however, whereas at stations 1 to 4 products were confined to the upper 50 m, at station 11 products were detected throughout the water column, down to a depth of 95 m. At each of these stations the brightest signals were at a depth of 10 m (data not shown). No cyanobacterial nifH products were detectable at the other stations along the transect when this primer pair was used.

Genetic diversity of cyanobacterial diazotrophs along the AMBITION cruise transect.

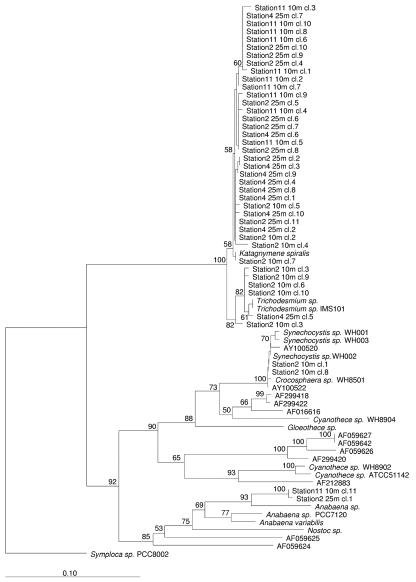

Clone libraries of 16S rDNA and nifH were constructed by using the CYA359F-NITRO821R and CNF-CNR primer pairs, respectively, for station 2 at depths of 10 and 25 m, for station 4 at a depth of 25 m depth, and for station 11 at a depth of 10 m. All sequenced 16S rDNA clones from these environmental libraries fell in the UCYN2-fix lineage (Fig. 6). The majority of the sequences (27 of 40 sequences), all derived from station 2 or 11, were phylogenetically most closely related to Crocosphaera sp. strain WH 8501. Within this group of sequences, those obtained from station 11 formed a distinct clade. 16S rDNA sequences from station 4 formed two separate clusters within the lineage and were generally not closely related to any known cultured unicellular diazotroph. Of the 40 environmental sequences obtained along the transect, clone 8 obtained from station 4 at a depth of 25 m and clone 5 obtained from station 11 at a depth of 10 m showed the greatest diversity (93.6% identity for the 462-bp product), suggesting that there is wide genetic diversity of these organisms in the Arabian Sea region.

FIG. 6.

Phylogenetic tree showing the relationships of the AMBITION cruise CYA359F-NITRO821R environmental 16S rDNA sequences. Each AMBITION cruise environmental sequence is referred to by station number, depth of sampling, and clone (cl.) number. The tree was constructed by the neighbor-joining method with Jukes-Cantor correction based on nearly full-length 16S rDNA sequences from marine and freshwater cyanobacteria. The percentages of bootstrap replicates supporting the branching order are indicated at the nodes. Partial sequences (e.g., sequences of the 462-bp product amplified by the CYA359F-NITRO821R primer set and other sequences <1,190 nucleotides long) were added to the tree by using a maximum-parsimony option within ARB. The cyanobacterium Gloeobacter violaceus PCC7421 was used as a root. The scale bar represents the equivalent of 0.1 substitution per nucleotide.

The overwhelming majority of nifH sequences obtained from the four clone libraries (38 of 42 sequences) were closely related to the Trichodesmium-Katagnymene group (Fig. 7), which is consistent with the observed presence of filaments of these organisms as determined from surface plankton tows (K. Orcutt, unpublished data). Interestingly, though, two sequences were obtained from station 2 at a depth of 10 m which were 99.7% identical to nifH from Crocosphaera sp. strain WH 8501, while two other sequences, one from station 11 at a depth of 10 m and one from station 2 at a depth of 25 m, were phylogenetically more similar to Anabaena spp. (Fig. 7).

FIG. 7.

Phylogenetic tree showing the relationships of the AMBITION cruise environmental nifH sequences. Each AMBITION cruise environmental sequence is referred to by station number, depth of sampling, and clone (cl.) number. The tree was constructed by the neighbor-joining method with Jukes-Cantor correction based on partial nifH sequences (e.g., a 359-bp fragment amplified with the CNF-CNR PCR primer set used in this study). The percentages of bootstrap replicates supporting the branching order are indicated at the nodes. The cyanobacterium Symploca sp. strain PCC8002 was used as the root. The scale bar represents the equivalent of 0.1 substitution per nucleotide.

Role of sea temperature in defining the distribution of the UCYN2-fix lineage along the AMBITION cruise transect.

The distribution of the UCYN2-fix lineage along the AMBITION cruise transect was compared to environmental parameters, including water column temperature and inorganic nutrient concentrations (specifically, the concentrations of nitrate and soluble reactive phosphate [SRP]). The nitrate concentrations varied between <0.01 and 0.15 μM and between <0.02 and 20 μM in the top 50 m at stations 1 to 7 and 8 to 11, respectively, and the SRP concentrations varied between 0.02 and 2.5 μM at all stations (M. Woodward unpublished data). The water column temperature showed a strong trend with the distribution of the unicellular diazotroph lineage (Fig. 8), and the organisms appeared generally to be preferentially located in warm (>29°C) oligotrophic subsurface waters. In cooler oligotrophic waters (<29°C) these organisms were absent or the numbers were considerably reduced.

FIG. 8.

Plot of the relative abundance of the UCYN2-fix lineage along the AMBITION cruise transect as a function of seawater temperature.

DISCUSSION

We describe here the design and utilization of a 16S rDNA oligonucleotide, NITRO821R, which we used in the PCR to detect marine unicellular cyanobacterial diazotrophs. This primer recognizes all known cultured isolates and environmental sequences in a well-defined lineage (Fig. 1), which suggests that it should have broad utility for detection of these organisms in the natural environment. Confirmation that the cyanobacterial symbionts of the marine diatom C. frauenfeldianum can fix atmospheric dinitrogen is still required, however. This would require isolation of these cyanobacterial symbionts in axenic culture. Assuming that such organisms do fix nitrogen, then the NITRO821R primer shows excellent specificity for marine unicellular cyanobacterial diazotrophs, particularly in conjunction with the cyanobacterium- and plastid-specific primer CYA359F (19), in PCRs (Fig. 3), as shown in this study.

Several 16S rDNA sequences of freshwater unicellular cyanobacterial diazotrophs which represent the genera Gloeocapsa, Gloeothece, and Aphanothece (accession numbers AB067575 to AB067581 and AB119259) and which are in the UCYN2-fix lineage described here (data not shown) have recently been deposited in the GenBank database. These sequences are also targeted with complete identity by the NITRO821R oligonucleotide, which potentially broadens its utility to freshwater systems. However, care is needed when this primer is used to enumerate this lineage in freshwater environments, given that we have shown that sequences of members of the genus Planktothrix, with a 1-bp mismatch with the NITRO821R primer, are amplified in PCRs with the CYA359F-NITRO821R primer pair. Specific size fractionation of freshwater environmental samples to remove the filamentous Planktothrix spp. would be one route to circumvent such a problem.

The utility of this molecular approach for revealing the distribution of unicellular cyanobacterial diazotrophs in natural marine systems appears to be well demonstrated, however, by the data obtained along the AMBITION cruise transect. Although the relative abundance compared to the nondiazotrophic picocyanobacterial genera Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus, which were the dominant organisms at the southern and northern stations, respectively (G. Tarran unpublished data), was low, significant numbers of the UCYN2-fix lineage were detectable, as determined by the semiquantitative analytical PCR developed in this study. Interestingly, the range of cell abundance observed along this single transect (7 × 103 ± 1.6 × 102 to 3.8 × 105 ± 8 × 104 cells liter−1) is very similar to the range of average cell counts of unicellular cyanobacteria in the 2.5- to 7-μm size class reported by Falcon et al. (10) for the tropical North Atlantic and subtropical North Pacific. In that study the cell numbers in the two ocean systems were considerably different, and it was proposed that the higher Fe flux to the North Atlantic was one of the factors that were important in determining the abundance of these organisms. Although we have no data on Fe flux at the different stations along the AMBITION cruise transect, this ocean basin is known to have high and variable deposition of dust (24), which results in pulsed iron addition in this region (14). Certainly, the fact that markedly different relative abundance values for the UCYN2-fix lineage were observed along this transect shows that the abundance of these organisms can vary considerably over relatively small spatial scales. Indeed, a comparison of a suite of environmental parameters obtained from the AMBITION cruise suggests that seawater temperature (Fig. 8) accompanied by low surface SRP and nitrogen levels (generally <0.25 μM) is significant in shaping the conditions in which these organisms can proliferate. Temperature has recently been shown to be important in dictating the distribution of heterocystous and nonheterocystous cyanobacteria in oceanic systems (23). In that study, differences in the temperature dependence of oxygen flux, respiration, and N2 fixation activity were shown to be critical in explaining how Trichodesmium performs better than heterocystous species at higher temperatures, and it may be that some of these factors are important for unicellular nitrogen-fixing species too.

The construction of environmental clone libraries based on the CYA359F-NITRO821R primer pair allowed us to obtain direct insight into the diversity of the UCYN2-fix lineage along the AMBITION cruise transect. The wide genetic diversity among the derived 16S rDNA sequences for the three stations analyzed was noticeable (the lowest level of identity was 93.6% for the 462-bp product), and this diversity was much greater than the diversity that has been found for the picocyanobacterial genera Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus (11, 26), for which the lowest levels of identity between strains and environmental sequences were 96 to 97% (for sequences usually >1,000 bp long) in their respective lineages. How this translates to physiological diversity requires further culture isolation since several of the sequences, particularly those from station 4, had no closely related cultured counterparts. Within a station, particularly stations 2 and 11, the genetic diversity observed was generally lower, and interestingly, sequences from the same station formed discrete clusters or clades (Fig. 6), suggesting the potential for ecotype adaptation of members of the UCYN2-fix lineage in specific water columns. The utility of the CYA359F-NITRO821R primer pair for focusing directly on the UCYN2-fix lineage is mirrored by data for the nifH clone libraries, where the primers used are not targeted to a particular cyanobacterial lineage. Here, sequences closely related to the Trichodesmium-Katagnymene group dominated the libraries. Two sequences from station 2, however, were closely related to the nifH sequence of Crocosphaera sp. strain WH 8501, which was in good agreement with the 16S rDNA environmental sequence data from that station, where sequences closely related to this strain dominated. These sequences thus correspond to the group B nifH sequences designated by Zehr et al. (34), while the group A nifH sequences reported in that study may be related to the deeply branching 16S rDNA clusters that include the station 4 clones.

Given the wide utility of the nifH gene for investigating the diversity of marine nitrogen fixers (32, 33, 35), it is noteworthy that we also obtained two environmental sequences (from stations 2 and 11) whose closest known relatives are nifH sequences from Anabaena sp. We found no previous reports of nifH sequences from members of this genus for oligotrophic open-ocean marine environments. However, these sequences may well be equivalent to the sequence of the novel Anabaena sp. described by Carpenter and Janson (8), who reported the presence of a heterocystous cyanobacterium in the southwest Pacific Ocean and Arabian Sea at a low level (1 to 4 trichomes liter−1).

The NITRO821R oligonucleotide and the analytical PCR developed here thus provide an excellent tool for rapid and sensitive screening of environmental samples to establish the presence and relative abundance of unicellular cyanobacterial diazotrophs, organisms that play important roles in oceanic new production and biogeochemistry. Use of the oligonucleotide in fluorescent in situ hybridization or quantitative PCR experiments, in which absolute quantitation of cell numbers can be obtained, or use in reverse transcription-PCR to determine the members of the community that are active in situ would further enhance its value.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to John Waterbury for providing Cyanothece and Crocosphaera cultures and B. Handley for providing P. rubescens cells used in this study. The efforts of the captain and crew of the RRS Charles Darwin, on which the AMBITION cruise took place, are also warmly appreciated. We also thank Jon Zehr for critical reading of the manuscript and Matthew Church for helpful discussions.

This work was funded by NERC grant GST/02/2819 under the Marine and Freshwater Microbial Biodiversity initiative, as well as by research development grant SC 02009 from the University of Warwick. O.B. was the recipient of a Society for General Microbiology summer studentship.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schäffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campbell, L., H. Liu, H. A. Nolla, and D. Vaulot. 1997. Annual variability of phytoplankton and bacteria in the subtropical North Pacific Ocean at station ALOHA during the 1991-1994 ENSO event. Deep-Sea Res. Part I 44:167-192. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Capone, D. G., J. P. Zehr, H. W. Paerl, B. Bergman, and E. J. Carpenter. 1997. Trichodesmium, a globally significant marine cyanobacterium. Science 276:1221-1229. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Capone, D. G., and E. J. Carpenter. 1999. Nitrogen fixation by marine cyanobacteria: historical and global perspectives. Bull. Inst. Oceanograph. (Monaco) 19:235-256. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Capone, D. G. 2000. The marine nitrogen cycle, p. 455-493. In D. Kirchman (ed.), Microbial ecology of the ocean. Wiley-Liss, New York, N.Y.

- 6.Capone, D. G. 2001. Marine nitrogen fixation: what's the fuss? Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 4:341-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carpenter, E. J., and S. Janson. 2000. Intracellular cyanobacterial symbionts in the marine diatom Climacodium frauenfeldianum (Bacillariophyceae). J. Phycol. 36:540-544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carpenter, E. J., and S. Janson. 2001. Anabaena gerdii sp. nov., a new planktonic filamentous cyanobacterium from the South Pacific Ocean and Arabian Sea. Phycologia 40:105-110. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Falcon, L. I., F. Cipriano, A. Y. Chistoserdov, and E. J. Carpenter. 2002. Diversity of diazotrophic unicellular cyanobacteria in the tropical North Atlantic Ocean. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:5760-5764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Falcon, L. I., E. J. Carpenter, F. Cipriano, B. Bergman, and D. G. Capone. 2004. N2 fixation by unicellular bacterioplankton from the Atlantic and Pacific oceans: phylogeny and in situ rates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:765-770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fuller, N. J., D. Marie, F. Partensky, D. Vaulot, A. F. Post, and D. J. Scanlan. 2003. Clade-specific 16S ribosomal DNA oligonucleotides reveal the predominance of a single marine Synechococcus clade throughout a stratified water column in the Red Sea. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:2430-2443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karl, D. M., A. Michaels, B. Bergman, D. G. Capone, E. Carpenter, R. Letelier, F. Lipschultz, H. Paerl, D. Sigman, and L. Stal. 2002. Dinitrogen fixation in the world's oceans. Biogeochemistry 57/58:47-98. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ludwig, W., O. Strunk, R. Westram, L. Richter, H. Meier, Yadhukumar, A. Buchner, T. Lai, S. Steppi, G. Jobb, W. Förster, I. Brettske, S. Gerber, A. W. Ginhart, O. Gross, S. Grumann, S. Hermann, R. Jost, A. König, T. Liss, R. Lüßmann, M. May, B. Nonhoff, B. Reichel, R. Strehlow, A. Stamatakis, N. Stuckmann, A. Vilbig, M. Lenke, T. Ludwig, A. Bode and K.-H. Schleifer. 2004. ARB: a software environment for sequence data. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:1363-1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Measures, C. I., and S. Vink. 1999. Seasonal variations in the distribution of Fe and Al in the surface waters of the Arabian Sea. Deep-Sea Res. Part II 46:1597-1622. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mitsui, A., S. Kumazama, A. Takahashi, H. Ikemoto, S. Cao, and T. Arai. 1986. Strategy by which nitrogen-fixing unicellular cyanobacteria grow photoautotrophically. Nature 323:720-722. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mitsui, A., S. Cao, A. Takahashi, and T. Arai. 1987. Growth of synchrony and cellular parameters of the unicellular nitrogen-fixing marine cyanobacterium, Synechococcus sp. strain Miami BG 043511, under continuous illumination. Physiol. Plant. 69:1-8. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mulholland, M. R., and D. G. Capone. 2000. The nitrogen physiology of the marine N2-fixing cyanobacteria Trichodesmium spp. Trends Plant Sci. 5:148-153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neveux, J., F. Lantoine, D. Vaulot, D. Marie, and J. Blanchot. 1999. Phycoerythrins in the southern tropical and equatorial Pacific Ocean: evidence for new cyanobacterial types. J. Geophys. Res. 104:3311-3321. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nübel, U., F. Garcia-Pichel, and G. Muyzer. 1997. PCR primers to amplify 16S rRNA genes from cyanobacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:3327-3332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olson, J. B., T. F. Steppe, R. W. Litaker, and H. W. Paerl. 1998. N2-fixing microbial consortia associated with the ice cover of Lake Bonney, Antarctica. Microb. Ecol. 36:231-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reddy, K. J., J. B. Haskell, D. M. Sherman, and L. A. Sherman. 1993. Unicellular, aerobic nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria of the genus Cyanothece. J. Bacteriol. 175:1284-1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sherman, L. A., P. Meunier, and M. S. Colon-Lopez. 1998. Diurnal rhythms in metabolism: a day in the life of a unicellular, diazotrophic cyanobacterium. Photosynth. Res. 58:25-42. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Staal, M., F. J. R. Meysman, and L. J. Stal. 2003. Temperature excludes N2-fixing heterocystous cyanobacteria in the tropical oceans. Nature 425:504-507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tinsdale, N. W., and P. P. Pease. 1999. Aerosols over the Arabian Sea: atmospheric transport pathways and concentrations of dust and sea salt. Deep-Sea Res. Part II 46:1577-1595. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Turner, S., T. C. Huang, and S. M. Chaw. 2001. Molecular phylogeny of nitrogen-fixing unicellular cyanobacteria. Bot. Bull. Acad. Sin. 42:181-186. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Urbach, E., D. J. Scanlan, D. L. Distel, J. B. Waterbury, and S. W. Chisholm. 1998. Rapid diversification of marine picophytoplankton with dissimilar light harvesting structures inferred from sequences of Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus (Cyanobacteria). J. Mol. Evol. 46:188-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wasmund, N., M. Voss, and K. Lochte. 2001. Evidence of nitrogen fixation by non-heterocystous cyanobacteria in the Baltic Sea and re-calculation of a budget of nitrogen fixation. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 214:1-14. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Waterbury, J. B., S. W. Watson, and F. W. Valois. 1988. Temporal separation of photosynthesis and dinitrogen fixation in the marine unicellular cyanobacterium Erythrosphaera marina. Eos 69:1089. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Webb, E. A., J. W. Moffett, and J. B. Waterbury. 2001. Iron stress in open-ocean cyanobacteria (Synechococcus, Trichodesmium, and Crocosphaera spp.): identification of the IdiA protein. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:5444-5452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.West, N. J., and D. J. Scanlan. 1999. Niche-partitioning of Prochlorococcus populations in a stratified water column in the eastern North Atlantic Ocean. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:2585-2591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.West, N. J., W. A. Schonhuber, N. J. Fuller, R. I. Amann, R. Rippka, A. F. Post, and D. J. Scanlan. 2001. Closely related Prochlorococcus genotypes show remarkably different depth distributions in two oceanic regions as revealed by in situ hybridization using 16S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotides. Microbiology 147:1731-1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zehr, J. P., M. T. Mellon, and W. D. Hiorns. 1997. Phylogeny of cyanobacterial nifH genes: evolutionary implications and potential applications to natural assemblages. Microbiology 143:1443-1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zehr, J. P., M. T. Mellon, and S. Zani. 1998. New nitrogen-fixing microorganisms detected in oligotrophic oceans by amplification of nitrogenase (nifH) genes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:3444-3450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zehr, J. P., J. B. Waterbury, P. J. Turner, J. P. Montoya, E. Omoregie, G. F. Steward, A. Hansen, and D. M. Karl. 2001. Unicellular cyanobacteria fix N2 in the subtropical North Pacific Ocean. Nature 412:635-638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zehr, J. P., B. D. Jenkins, S. M. Short, and G. F. Steward. 2003. Nitrogenase gene diversity and microbial community structure: a cross-system comparison. Environ. Microbiol. 5:539-554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]