Abstract

Bacteria inhibitory to fish larval pathogenic bacteria were isolated from two turbot larva rearing farms over a 1-year period. Samples were taken from the rearing site, e.g., tank walls, water, and feed for larvae, and bacteria with antagonistic activity against Vibrio anguillarum were isolated using a replica plating assay. Approximately 19,000 colonies were replica plated from marine agar plates, and 341 strains were isolated from colonies causing clearing zones in a layer of V. anguillarum. When tested in a well diffusion agar assay, 173 strains retained the antibacterial activity against V. anguillarum and Vibrio splendidus. Biochemical tests identified 132 strains as Roseobacter spp. and 31 as Vibrionaceae strains. Partial sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene of three strains confirmed the identification as Roseobacter gallaeciensis. Roseobacter spp. were especially isolated in the spring and early summer months. Subtyping of the 132 Roseobacter spp. strains by randomly amplified polymorphic DNA with two primers revealed that the strains formed a very homogeneous group. Hence, it appears that the same subtype was present at both fish farms and persisted during the 1-year survey. This indicates either a common, regular source of the subtype or the possibility that a particular subtype has established itself in some areas of the fish farm. Thirty-one antagonists were identified as Vibrio spp., and 18 of these were V. anguillarum but not serotype O1 or O2. Roseobacter spp. strains were, in particular, isolated from the larval tank walls, and it may be possible to establish an antagonistic, beneficial microflora in the rearing environment of turbot larvae and thereby limit survival of pathogenic bacteria.

The use of probiotics for disease control in aquaculture is an area of increasing interest, as the use of antibiotics is causing concern over the possible development of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Probiotics have been defined by the World Health Organization-Food and Agriculture Organization (13) as “live microorganisms which when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host.” In the past decade, several gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria have been evaluated in vitro or in vivo for their potential to inhibit fish-pathogenic organisms and overcome infections in fish and larvae in aquaculture (17, 23). Some studies have used bacterial strains, e.g., lactic acid bacteria, from culture collections; however, most studies have used bacteria isolated from the surface or gastrointestinal tract of fish or fish larvae (17).

The proliferation and/or infection site of fish pathogens is often not known, and the mechanisms of antagonism by a probiotic culture towards a fish pathogen are often not understood. All these parameters would influence the choice of a probiotic bacterium. For instance, probiotic bacteria isolated from the gut would appear promising if the target pathogenic bacteria infect via the gastrointestinal tract. Some fish pathogens may proliferate on the skin surface (40), and probiotic bacteria adapted to the outer surfaces could limit pathogen proliferation. Moriarty (31) suggested that probiotic cultures could also originate from the general rearing environments, and since Bacillus spp. are generally present in the sediment from which shrimp are feeding, he added a commercialized Bacillus product to the water in shrimp culture and successfully prevented infection by pathogenic vibrios (30). Also, Marco-Noales et al. (28) recently demonstrated that levels of Vibrio vulnificus in water were influenced (suppressed) by the presence of other bacteria.

Based on the above-mentioned investigations (28, 30), it is plausible that health-beneficial organisms in a fish rearing system may be found in several other niches than the fish itself. Indeed, we (21) recently isolated potential probiotic bacteria from a turbot rearing unit, and bacteria that were inhibitory towards turbot larval pathogens in vitro were specifically isolated from tank walls and rotifer feeding on Rhinomonas. The inhibitory strains were identified as either Roseobacter spp. or Vibrio spp. Small-scale in vivo trials of adding Roseobacter strains to the water of egg yolk sac larvae demonstrated a disease-preventing effect of Roseobacter sp. strain 27-4. These findings underline the idea that probiotic bacteria may be present and exert their effects from the general environment (water, tank walls, etc.) and may not need to originate from, and be able to colonize, the fish (larvae). Large differences are seen in survival performance between lots of fish larvae and between tanks or units, and one could hypothesize that such differences could be explained partly by differential colonization of pathogen-antagonizing bacteria in the system.

It is not known if particular niches or seasons select for bacteria antagonizing fish-pathogenic bacteria or if different bacterial species appear at different seasons. These aspects would be important when applying probiotic cultures as a disease management strategy. The purpose of the present study was therefore to determine if bacteria with antagonistic activity against turbot larval pathogens were present in turbot larval rearing units at specific sites and/or times and whether these were the same species or changed according to season.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

The target bacterium for screening potential probiotic bacteria was Vibrio anguillarum strain 90-11-287, serotype O1, originally isolated from rainbow trout (39). It is highly virulent and causes mortality in infection trials with both turbot larvae (21) and rainbow trout (18). Vibrio splendidus strain DMC-1 (21, 43), isolated from a turbot larval rearing unit experiencing high mortalities, was also used. Three antagonistic strains were used as positive controls in replica and well diffusion assays. Vibrionaceae strain T3 (Danish Institute for Fisheries Research culture collection), isolated from cod, was used in the replica plating procedure. Pseudomonas fluorescens strain AH2 (18) (AF451275) and Roseobacter sp. strain 27-4 (21) were used in the well diffusion assay. The following strains were used as controls in the phenotypic identification procedures: Roseobacter sp. strain 27-4 (21), Roseobacter denitrificans (DSM 7001), Roseobacter gallaeciensis (DSM 12440), Pseudoalteromonas sp. strain HQ (21) (AY227707), P. fluorescens strain AH2, Alcaligenes aquamarinus type strain ATCC 14400, Shewanella putrefaciens type strain ATCC 8071, Shewanella baltica type strain ATCC 22, V. anguillarum 90-11-287, V. splendidus DMC-1, Aeromonas sp. strain F1 (Danish Institute for Fisheries Research culture collection), and Photobacterium augustum type strain ATCC 25915. All strains were routinely grown in marine broth (MB; Difco catalog no. 279110) or on marine agar (MA; Difco catalog no. 212185) at 20°C for 1 to 3 days.

Sampling.

Samples for microbiological analyses were taken once a month from two turbot rearing fish farms in northwestern Spain. Water samples, swabs from tank walls, and samples of larvae at different feeding stages (i.e., fed on rotifer, rotifer and Artemia, or Artemia only) were taken from larval rearing tanks. Also rotifers fed on different types of algae (Isochrysis and Rhinomonas) and Artemia nauplii (disinfected or nondisinfected) were sampled. Sterile gloves, bags, swabs, and plastic beakers were used for sampling. All samples were 10-fold diluted in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 8.0 g of NaCl, 0.3 g of KCl, 0.73 g of NaH2PO4, and 0.2 g of K2HPO4 to 1 liter of deionized water, pH 7.4) and spread plated onto MA. Water samples and rotifer fed on algae were diluted directly. Cotton swabs were placed in stomacher bags and squeezed by hand with 5 ml of PBS (constituting a 100 dilution) for a few minutes and diluted. Artemia samples were left to settle, and approximately 1 g of aggregate was mixed with PBS and regarded as a 10−1 dilution. After incubation at 20°C for 3 to 4 days, plates with between 5 and 400 colonies were selected and sent by courier to Denmark in a polystyrene box, arriving within 24 h. Plates were stored at 10°C until replica plating.

Replica plating.

MA plates were replica plated on agar plates mixed with V. anguillarum, and colonies causing a zone of clearing in the fish pathogen agar layer were selected for further analysis (21). Ten milliliters of M9 minimal medium (37) containing M9 salts, 3% NaCl, 0.4% glucose, 0.3% Casamino Acids (Bacto 223050; Becton Dickinson, Sparks, Md.), 2 mM MgSO4, and 0.1 mM CaCl2 and 1.2% agar (hereafter called M9GC-3) was mixed with 10 μl of 108 to 109 CFU of V. anguillarum/ml grown in MB for 24 h at 20°C. After solidification, MA plates were replica plated using Whatman filter paper (no. 4) to transfer colonies to M9GC-3 plates. Vibrionaceae strain T3 was 10-fold diluted, and plates with 10 to 30 colonies were replica plated as a positive control. After incubation for 24 h at 20°C, colonies causing clearing zones were isolated from the primarily MA plates (1 to 12 colonies from each sample), pure cultured, and stored at −80°C.

Well diffusion agar assay.

Strains isolated as causing zones of clearing in the replica-plating procedure were subsequently tested in a well diffusion assay to confirm inhibitory activity against V. anguillarum and V. splendidus. Ten and 600 μl, respectively, were mixed into 10 ml of warm (43.5°C for V. splendidus and 44°C for V. anguillarum) M9GC-3 substrate. Pure cultured strains from −80°C were grown for 3 days in MB at 20°C and recultured for 2 days, and then 10 μl was transferred into wells (3-mm diameter) in the solidified M9GC-3 substrate. Plates were incubated at 20°C for 1 day and read for zones of clearing (indicating inhibition of the fish pathogen) in the turbid agar. Only strains inhibitory to the fish pathogens in the well diffusion assay were selected for further studies. P. fluorescens AH2 and Roseobacter sp. strain 27-4 were used as positive-control strains.

Identification of bacteria.

Bacterial strains were tentatively identified using a set of biochemical-phenotypic tests. Gram reaction was tested using Bactident aminopeptidase strips (Merck catalog no. 1.13301). Motility and shape were assessed by phase-contrast microscopy (1,000× magnification) on cultures grown in MB at 20°C. Catalase (3% H2O2) and oxidase (BBL Dryslide oxidase slides; Becton Dickinson) were tested on cultures grown on MA. Ability to metabolize glucose by fermentation or oxidation (22) was tested in oxidation-fermentation basal medium (Merck catalog no. 1.10282) supplemented with 2% Instant Ocean (IO; Aquarium Systems Inc., Sarrebourg, France).

Strains tentatively identified as Vibrionaceae (gram-negative, motile, fermentative rods with positive oxidase and catalase reactions) were tested for sensitivity to vibriostaticum O/129 (150 μg; Oxoid catalog no. 129150) and for the ability to grow without NaCl (10 g of tryptone, 5 g of yeast extract per liter) and in the API system (Biomerieux API 20 NE 20 050). Since many of the marine isolates require a mixture of marine salts to grow, 0.35 ml of a sterile 20% IO solution was added to the 7-ml API dilution tubes, leading to a final concentration in the diluent of 1.85% salts.

Gram-negative, motile rod-shaped bacteria, which did not ferment or oxidize glucose in oxidation-fermentation tubes and were positive in catalase and oxidase tests, were further grouped according to tentative identification procedures as in the work of Hjelm et al. (21). The ability of Shewanella to reduce trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO) was tested according to the method of Gram et al. (19), and the presence of arginine dihydrolase activity (decarboxylase base Moeller; Difco catalog no. 289010; supplemented with 2% IO) was tested according to the work of Alsina and Blanch (2). A minimal medium (7, 8) was used to test assimilation of d-sorbitol or dl-malate (10 g/liter) in microtiter plates. Prior to inoculation, strains were grown on MA. Colonies were suspended in 10 ml of saline (1.5% NaCl) to produce visible turbidity. Twenty-five microliters was added to 225 μl each of the assimilation substrate (in duplicate), and plates were incubated at 20°C. Glucose was used as positive control (except for Alcaligenes). The medium without a carbon source served as a negative control. Growth was determined as an increase in optical density of ≥0.05 at 600 nm for up to 4 weeks. For several strains growth was not detected until after 3 weeks.

The identity of three selected strains was verified by partial sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene (by Deutche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen, Braunschweig, Germany).

RAPD analysis.

Of a total of 173 strains, 132 were tentatively identified as Roseobacter species. To determine if the strains isolated constituted a permanent colonization of the rearing unit or if a constant flux of new strains were coming in, the strains were subtyped using randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) analysis (12) with primers UBC 104 (5′ GGG CAA TGA T) and UBC 106 (5′ CGT CTG CCC G) (synthesized by DNA Technology, Aarhus, Denmark). Briefly, DNA was extracted from 400 μl of bacterial culture by using magnetic beads (Dynabeads, DNA direct, Universal; Dynal ASA, Oslo, Norway). One Ready-To-Go RAPD analysis bead (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech catalog no. 27-9500-01; Piscataway, N.J.) was added to each sample followed by 23 μl of primer (1.0 μM). The PCR was run in a thermocycler (Perkin-Elmer 9600; Norwalk, Conn.) with the template DNA. After denaturation for 2 min at 95°C, the next 10 cycles were of 1 min of denaturation at 95°C followed by annealing at 45°C and reduction to 36°C by 1°C for each cycle and then by extension for 2 min at 72°C. The last 30 cycles used denaturation at 95°C for 1 min followed by annealing at 35°C and extension at 72°C for 2 min. Electrophoresis of 24 μl of product in a 2% agarose gel at 90 V for 4 h was followed by visualization by staining with 3 μg of ethidium bromide per ml for 30 min and viewing with a transilluminator. A 100-bp ladder (catalog no. 24-40001-01; Pharmacia Biotech Inc.) was included three times in each gel.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The 16S rRNA gene sequence for V. splendidus strain DMC-1 has been deposited with GenBank under accession no. AY227706. Partial sequences of the 16S rRNA genes from three strains from the Roseobacter group have been deposited in GenBank under the accession numbers AY583736 to AY583738.

RESULTS

Samples with antagonistic bacteria.

The two turbot rearing farms selected for the present 1-year survey were sites where potential probionts had previously been detected in October 2001 (21). All 135 samples were taken from environments in which turbot larvae performed well. In total, approximately 19,000 colonies were replica plated from MA plates.

From farm I, 31 of 73 samples had bacterial colonies that were able to inhibit V. anguillarum in the replica-plating assay, but when strains were tested for antibacterial activity in the well diffusion assay, the number was reduced to 24 samples (Table 1). At farm II, 20 of 62 samples caused clearing zones in the replica-plating assay. Subsequent testing of pure cultures reduced this to 12 samples, from which bacteria with sustained antibacterial activity were isolated. Sampling was conducted once a month, and the type and number of samples depended on the actual ongoing production, which explains the variation in the number of samples.

TABLE 1.

Numbers of samples taken at two turbot larva rearing farms over a 1-year period

| Farm | Year | Montha | No. of samples | No. of samples with inhibitory strains from:

|

No. of Roseobacter strains | No. of Roseobacter strains with RAPD (UBC104) profile

|

No. of Vibrio strains | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Replica plating | WDAAb | Profile I | Other profiles | ||||||

| I | 2002 | Sept | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Oct | 5 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 3 | ||||

| Nov | 8 | 7 | 3 | 8 | 8 | 4 | |||

| Dec | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 | |||

| 2003 | Feb | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 | |||

| March | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| April | 9 | 6 | 4 | 22 | 20 | 2 of III | |||

| May | 9 | 4 | 4 | 26 | 26 | 1 | |||

| June | 9 | 2 | 2 | 14 | 11 | 2 of 8-1, 1 of II, 1 of III | |||

| July | 6 | 2 | 2 | 15 | 14 | 1 | |||

| Aug | 8 | 4 | 4 | 9 | 7 | 1 of III, 1 of IV | 1 | ||

| Subtotal | 73 | 31 | 24 | 95 | 87 | 8 | 24 | ||

| II | 2002 | Sept | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Oct | 8 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||||

| Nov | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||||

| Dec | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| 2003 | Feb | 5 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |||

| March | 5 | 3 | 3 | 21 | 21 | 3 | |||

| April | 8 | 4 | 3 | 9 | 8 | 1 of V | |||

| May | 8 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |||||

| June | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| July | 2 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 7c | 1 | |||

| Aug | 5 | 2 | 2 | 0 | |||||

| Subtotal | 62 | 20 | 12 | 37 | 36 | 1 | 7 | ||

| Grand total | 135 | 51 | 36 | 132 | 123 | 9 | 31 | ||

Abbreviations: Sept, September; Oct, October; Nov, November; Dec, December; Feb, February; Aug, August.

Well diffusion agar assay against V. anguillarum and V. splendidus.

Two strains lacked a 1,000-bp band (tested twice).

Pathogen-antagonizing bacteria (Roseobacter and Vibrionaceae) were detected in 9 out of 11 months on farm I and in 7 out of 11 months on farm II.

Identification of potential probionts.

A total of 173 strains were antagonistic against the two larval pathogenic bacteria in the well diffusion assay (Table 2). All were gram-negative, rod-shaped motile bacteria with positive catalase and oxidase reactions. Of the 173 strains, 142 did not ferment or oxidize glucose and were tentatively grouped as Pseudomonas (alkali-producing), Pseudoalteromonas, Roseobacter, Shewanella, or Alcaligenes (marine) strains. The majority of these (132) were identified as Roseobacter spp. according to the work of Hjelm et al. (21). All strains produced a brown pigment when plated on MA. None of the strains reduced TMAO to trimethylamine, and none hydrolyzed arginine. All strains assimilated malate, and 121 assimilated sorbitol. The lack of assimilation of sorbitol does not distinguish within the group of Roseobacter strains.

TABLE 2.

Numbers and types of samples from two turbot larva rearing farms and the identification of antagonistic bacteria from different samples

| Farm | Type of samples | No. of samples with:

|

No. of strains from replica | No. of potential probionts

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Clear zones on replica | Potential probionts | Total | Roseobacter | Vibrionaceae | Pseudomonas (alkali) | Shewanella | Others | |||

| I | Tank wall | 15 | 11 | 11 | 71 | 63 | 7 | 1 | |||

| Tank water | 15 | 9 | 8 | 16 | 14 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Larvae fed with rotifers | 12 | 7 | 4 | 28 | 13 | 15 | |||||

| Larvae fed with Artemia | 2 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 5 | 1 | |||||

| Larvae fed on rotifers and Artemia | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||

| Artemia, disinfected | 10 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||

| Artemia, not disinfected | 1 | 1 | 0 | ||||||||

| Rotifers fed on Rhinomonas | 8 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||

| Rotifers fed Isochrysis | 9 | 2 | 0 | ||||||||

| Subtotal | 73 | 31 | 24 | 224a | 121 | 95 | 24 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| II | Tank wall | 13 | 6 | 4 | 28 | 19 | 2 | 5 | 2 | ||

| Tank water | 13 | 5 | 3 | 12 | 9 | 1 | 2 | ||||

| Larvae fed with rotifers | 7 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Larvae fed with Artemia | 2 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 7 | 1 | |||||

| Larvae fed on rotifers and Artemia | 4 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | ||||||

| Artemia, disinfected | 11 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||||||

| Rotifers fed Isochrysis | 12 | 1 | 0 | ||||||||

| Subtotal | 62 | 20 | 12 | 117b | 53 | 37 | 7 | 2 | 5 | 1 | |

| Grand total | 135 | 51 | 36 | 341 | 174 | 132 | 31 | 3 | 5 | 3 | |

Approximately 10,000 replica-plated CFU.

Approximately 9,000 replica-plated CFU.

The 16S rRNA gene sequence was partially sequenced for three strains from the Roseobacter group. The partial sequences were identical, and the highest similarity was 99.8% to R. gallaeciensis (ATCC 23107T). The strains differed in their ability to assimilate sorbitol. One strain (234-2) did assimilate sorbitol, whereas strains 243-5T and 628-19 did not.

Of the remaining 10 nonfermentative strains, 3 were arginine dihydrolase positive and assimilated malate. Two of these did not assimilate sorbitol, but the metabolism is variable within the group. Thus, the strains were grouped as alkali-producing Pseudomonas strains. Five strains were able to reduce TMAO to trimethylamine, did not assimilate sorbitol, and were identified as Shewanella. Two strains could not be identified.

Thirty-one strains fermented glucose, categorizing them as Vibrionaceae. All strains were sensitive to vibriostaticum, 29 of the strains were unable to grow in tryptone medium with 0% NaCl, and all were therefore grouped as Vibrio spp. Eighteen of the strains had similar colony morphology and were arginine dihydrolase positive but negative in ornithine and lysine decarboxylase. They were positive in the indole, o-nitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside, and Voges-Proskauer reactions. This profile identified the strains as V. anguillarum, and a subset of two strains were serotyped. One strain was serotype O4 positive, and the other was nontypeable with a weak cross-reaction to O3, O7, and O10 sera which is typical of environmental V. anguillarum (25).

Sites with potential probiotic bacteria.

Bacteria with antagonistic properties were found only on tank walls, in tank water, and in larvae feeding on rotifers or Artemia in farm I. More than 50% of tank wall and water samples contained pathogen-antagonizing bacteria. From farm II, antagonistic bacteria were detected in all types of samples (i.e., tank walls, tank water, and larvae fed with rotifer and/or Artemia) except from “rotifers fed on Isochrysis.” A total of 29 samples from both farms were taken from “rotifer feeding on algae” (Rhinomonas or Isochrysis), and none of these samples contained antagonistic bacteria. Culturable counts in water samples ranged from 102 to 104 CFU ml−1, and antagonistic bacteria were isolated from 11 of 28 samples. Based on counts of brown-pigmented bacteria, Roseobacter constituted between 1 and 40% of the population in these samples.

Roseobacter spp. were isolated primarily from tank walls, and 82 of the 132 strains originated from such sites (Table 2). A smaller number (23 strains) were detected from tank water, and the remaining 27 Roseobacter strains were associated with larvae fed on rotifers and/or Artemia. Vibrionaceae strains were detected in several sample types but were most prominent in larvae feeding on rotifers in farm II (Table 2).

RAPD profiling of Roseobacter spp.

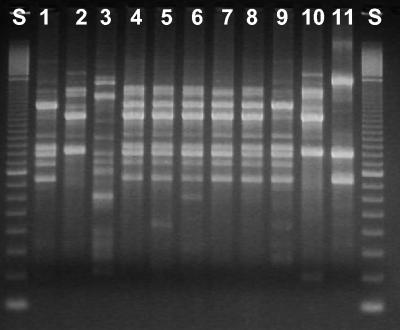

RAPD profiles of Roseobacter spp. were generated using two primers, and both resulted in almost the same subgrouping. The profiles were very homogeneous, and of the 132 strains analyzed with primer UBC 104, 123 strains had almost identical profiles (profile I) (Fig. 1). Two strains (codes 658-2 and 659-1) had profiles similar to profile I but lacked a 1,000-bp band on repeated testing (Table 3). With the use of primer UBC 106, 127 strains had identical profiles.

FIG. 1.

Profiling of Roseobacter strains by RAPD analysis with primer UCB 104. Lanes: S, standard; 1, 255-1 = 8-1; 2, 256-8 = 27-4; 3, 270-3; 4, 234-2 (RAPD type I); 5, 243-5(T) (RAPD type I); 6, 628-19 (RAPD type I); 7, 629-5a (RAPD type I); 8, 632-1 (RAPD type I); 9, Roseobacter 8-1; 10, Roseobacter 27-4; 11, R. gallaeciensis.

TABLE 3.

RAPD profile of Roseobacter strains isolated from sample sites on two turbot larva rearing farms

| Farm | Type of samples | No. of samples with Roseobacter | No. of Roseobacter strains | No. of RAPD profiles of Roseobacter strains (primer UBC 104)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Others | ||||

| I | Tank wall | 9 | 63 | 56 | 7a |

| Tank water | 6 | 14 | 14 | ||

| Larvae fed with rotifers | 2 | 13 | 12 | 1b | |

| Larvae fed with Artemia | 1 | 5 | 5 | ||

| II | Tank wall | 3 | 19 | 19c | |

| Tank water | 2 | 9 | 8c | 1 | |

| Larvae fed with Artemia | 1 | 7 | 7 | ||

| Larvae fed on rotifers and Artemia | 1 | 2 | 2 | ||

| Grand total | 25 | 132 | 123 | 9 | |

Including two strains with a RAPD profile identical to that of strain 8-1.

Profile similar to that of strain 27-4.

One strain lacks a 1,000-bp band.

Nine strains had a different profile with UBC 104. Two strains appeared to be identical to reference strain 8-1 (codes 255-1 and 255-2), and one strain was similar to another reference strain, 27-4 (256-8), both previously isolated from farm I in October 2001 (21). The remaining six strains (234-9, 234-10, 256-7, 267-1, 270-3, and 632-1) fell into different profiles. Primer UCB 106 confirmed that strain 256-8 was similar to strain 27-4 but that strain 8-1 (and hence codes 255-1 and 255-2) could not be distinguished from the common profile. Only three of the nine strains with different profiles from the primer UBC 104 were also different with primer UBC 106 (256-8, 270-3, and 632-9).

Roseobacter strains were detected in 7 of the 11 months sampled at farm I and in 4 of the 11 months sampled at farm II but were especially prominent in March and April (Table 1). RAPD profile I appeared at each sampling.

DISCUSSION

The present study demonstrates that bacteria with antagonistic properties against turbot larval pathogenic bacteria are present year-round in two turbot larva rearing units. The study also indicates that the bacterial groups displaying antagonistic activity were remarkably stable and that new species appear not to be introduced over time. In a previous study (21), we determined the antagonistic activity of 8,500 colonies by replica plating, resulting in a total of 32 strains (0.4%), which upon retesting retained antagonism. The “score rate” of the present study, i.e., 173 strains resulting from 19,000 colonies (0.9%), is slightly better and in the range reported by other studies (41).

Hjelm et al. (21) identified all antagonistic strains as either Roseobacter or Vibrio spp. In our present study covering significantly more samples and a wider time span, Roseobacter and Vibrio spp. were again the dominant antagonistic species. The finding of an alphaproteobacterium (Roseobacter spp.) as the dominant antagonist could indicate a selective pressure of the rearing environment. Thus, Long and Azam (26) reported that bacteria belonging to the gammaproteobacteria (Alteromonadales and Vibrionales) were the most prolific producers of an inhibitory substance(s) and also the most resilient.

A large proportion of the antagonistic bacteria were found on tank walls (15 out of 28 samples positive). Also, Long and Azam (26) found that attached and/or particle-associated bacteria displayed a higher degree of antibacterial activity than did free-living bacteria, indicating that attaching-persisting bacteria living in an environment of high bacterial density may be more antagonistic than free-living bacteria. Our finding that Roseobacter strains especially were associated with surfaces mirrors the finding by Dang and Lovell (9), who found that organisms belonging to the Roseobacter subgroup were ubiquitous and rapidly colonized surfaces in coastal environments. When surfaces were submerged in a salt marsh estuary tidal creek for 24 and 72 h, 22 clones out of 26 of the most abundant and most common in the library were affiliated with the Roseobacter subgroup (9). Also, dinoflagellates appear to be a niche area for Roseobacter in the marine environment (1, 11), and during algal blooms, Roseobacter may account for more than half of the rRNA gene sequence pool (16).

The Roseobacter group is attracting increasing attention among marine microbiologists as an important group of aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria (4, 38). It is estimated that, in some marine areas, Roseobacter clade-affiliated organisms account for 7 to 30% of the microbial population (14, 38), but they may also be present in lower proportions (i.e., 1%) (10). We found that brown-pigmented colonies similar to Roseobacter accounted for between 1 and 40% of the culturable bacteria in some water samples (data not shown). The Roseobacter clade consists of 12 or 13 genera (1, 29) such as Sulfitobacter, Roseovarius, Marinosulfomonas, and Silicibacter. All isolates, except one, have been isolated from marine or high-salt environments such as seawater, marine sediments, and surfaces of marine organisms (see the work of Moran et al. [29] for a review). As opposed to many other marine organisms (3, 28), Roseobacter strains are often culturable (29). The consistent finding in our study of Roseobacter as the dominant antagonistic bacterium in the larval rearing environment may hence be a logical reflection of its presence in high proportions in marine waters, its ability to be favored selectively by surface structures, and its preference for association with algal organisms. Many marine microorganisms are inhibitory to other organisms (26), and it was recently demonstrated that a Roseobacter isolate produced tropodithietic acid, which inhibited several gammaproteobacteria (6). This isolate was closely related to R. gallaeciensis, and it is not unlikely that the inhibitory activity of our isolates is caused by the same mechanism.

Vibrio spp. were isolated from several sites, notably in larvae feeding on rotifer (Table 2). Vibrionaceae are the most common members of the gut flora of feeding larvae (5, 20, 32), and Maeda et al. (27) found that rotifer cultures were favorable environments for Vibrio spp., probably due to the microaerophilic conditions selecting for fermentative organisms. Several other studies have also demonstrated that Vibrio spp. may be antagonistic towards fish-pathogenic bacteria (5, 44).

Vibrionaceae strains were present almost year round, and also Roseobacter strains were isolated at several sampling times. However, the number of isolated Roseobacter strains was especially high in March and April. This could indicate either that temperature, salinity, or soluble nutrients were particularly favorable during these months or that a common introduction, e.g., via the feed, occurred during that period. Moran et al. (29) indicated that temperature did not appear to limit distribution of Roseobacter strains; however, Selje et al. (38) concluded that the Roseobacter clade affiliates were predominantly found in polar and temperate waters and were rarely isolated in waters with temperatures above 20 to 25°C. Being a marine organism, Roseobacter is dependent on a saline environment, and numbers decrease as salinity decreases (15). The rearing environment is run at constant temperature and salinity; however, water is taken directly from the sea. Blooms of dinoflagellates often occur in spring months, and since Roseobacter is an especially common associate of dinoflagellates (1, 11, 16), such blooms could cause an increase in Roseobacter levels or water conditions could be particularly favorable, e.g., being rich in nutrients.

The subtyping procedure demonstrated that the population of Roseobacter was very stable during the 1-year survey, and this could indicate that a permanent population has been established, e.g., on the tank walls, reflecting the excellent biofilm-forming ability of the organism (9). Although the tanks are cleaned between rearing cycles, the attached state may render microorganisms more resistant to cleaning and disinfecting agents (35) and facilitate their survival. Alternatively, since Roseobacter strains are present in seawater at a level of up to 105 CFU/ml (38) and among the initial biofilm formers (9), they may enter the tanks and rapidly reestablish themselves.

Several studies have evaluated characteristics of potential probiotic bacteria and have studied the ability of the bacteria to adhere to intestine or skin mucus (24, 33, 34). However, most studies have found that added probiotic cultures are only transient and do not colonize the fish host (36, 42). Although this can be circumvented by daily additions of the probiotic culture, a more persistent establishment is likely to result in a more stable barrier towards the pathogen. Our finding that a pathogen-antagonizing bacterium has established itself in high densities in a larval rearing environment indicates that this could be a novel way of applying probiotic cultures. We believe that it is a simpler task to establish the culture on inert surfaces, where the colonization resistance of the live host need not be overcome.

Acknowledgments

The project was financed by the European Commission (contract no. Q5RS-2000-31457).

Valuable comments on the manuscript were provided by T. H. Birkbeck and Ph.D. student Jesper B. Bruhn, and we thank Jens Laurits Larsen and Morten Bruun for serotyping of V. anguillarum strains.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allgaier, M., H. Uphoff, A. Felske, and I. Wagner-Döbler. 2003. Aerobic anoxygenic photosynthesis in Roseobacter clade bacteria from diverse marine habitats. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:5051-5059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alsina, M., and A. R. Blanch. 1994. A set of keys for biochemical identification of environmental Vibrio species. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 76:79-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amann, R. L., W. Ludwig, and K. H. Schleifer. 1995. Phylogenetic identification and in situ detection of individual microbial cells without cultivation. Microbiol. Rev. 59:143-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Béjà, O., M. T. Suzuki, J. F. Heidelberg, W. C. Nelson, C. M. Preston, T. Hamada, J. A. Eisen, C. M. Fraser, and E. F. DeLong. 2002. Unsuspected diversity among marine aerobic anoxygenic phototrophs. Nature 415:630-633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bergh, Ø. 1995. Bacteria associated with early life stages of halibut, Hippoglossus-hippoglossus L, inhibit growth of a pathogenic Vibrio sp. J. Fish Dis. 18:31-40. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brinkhoff, T., G. Bach, T. Heidorn, L. Liang, A. Schlingloff, and M. Simon. 2004. Antibiotic production by a Roseobacter clade-affiliated species from the German Wadden sea and its antagonistic effects on indigenous isolates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:2560-2565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dalgaard, P., G. P. Manfio, and M. Goodfellow. 1997. Classification of Photobacteria associated with spoilage of fish products by numerical taxonomy and pyrolysis mass spectrometry. Zentbl. Bakteriol. 285:157-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dalgaard, P. 2004. Personal communication. Danish Institute for Fisheries Research, Lyngby, Denmark.

- 9.Dang, H., and C. Lovell. 2000. Bacterial primary colonization and early succession on surfaces in marine waters as determined by amplified rRNA gene restriction analysis and sequence analysis of 16S rRNA genes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:467-475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eilers, H., J. Pernthaler, J. Peplies, F. O. Glöckner, G. Gerdts, and R. Amann. 2001. Isolation of novel bacteria from the German Bight and their seasonal contributions to surface picoplankton. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:5134-5142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fandino, L. B., L. Riemann, G. F. Steward, R. A. Long, and F. Azam. 2001. Variations in bacterial community structure during a dinoflagellate bloom analyzed by DGGE and 16S rDNA sequencing. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 23:119-130. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fonnesbech Vogel, B., L. V. Jørgensen, B. Ojeniyi, H. H. Huss, and L. Gram. 2001. Diversity of Listeria monocytogenes isolates from cold-smoked salmon produced in different smokehouses as assessed by randomly amplified polymorphic DNA analyses. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 65:83-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Food and Agriculture Organization/World Health Organization. 2001. Evaluation of health and nutritional properties of powder milk and live lactic acid bacteria. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and World Health Organization expert consultation report. Food and Agriculture Organization, Rome, Italy.

- 14.Gonzalez, J. M., and M. A. Moran. 1997. Numerical dominance of a group of marine bacteria in the α-subclass of the class Proteobacteria in coastal seawater. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63:4237-4242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gonzalez, J. M., F. Mayer, M. A. Moran, R. E. Hodson, and W. B. Whitman. 1997. Sagittula stellata gen. nov., sp. nov., a lignin-transforming bacterium from a coastal environment. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 47:773-780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gonzalez, J. M., R. P. Kiene, and M. A. Moran. 1999. Transformation of sulfur compounds by an abundant lineage of marine bacteria in the alpha-subclass of the class Proteobacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:3810-3819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gram, L., and E. Ringø. Prospects of fish probiotics. In W. Holzapfel, and P. Naughton (ed.), Microbial ecology of growing animals, in press. Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- 18.Gram, L., J. Melchiorsen, B. Spanggaard, I. Huber, and T. F. Nielsen. 1999. Inhibition of Vibrio anguillarum by Pseudomonas fluorescens AH2, a possible probiotic treatment of fish. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:969-973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gram, L., G. Trolle, and H. H. Huss. 1987. Detection of specific spoilage bacteria from fish stored at low (0°C) and high (20°C) temperatures. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 4:65-72. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grisez, L., J. Reyniers, L. Verdonck, J. Swings, and F. Ollevier. 1997. Dominant intestinal microflora of sea bream and sea bass larvae from two hatcheries, during larval development. Aquaculture 155:387-399. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hjelm, M., Ø. Bergh, A. Riaza, J. Nielsen, J. Melchiorsen, S. Jensen, H. Duncan, P. Ahrens, H. Birkbeck, and L. Gram. 2004. Selection and identification of autochthonous potential probiotic bacteria from turbot larvae (Scophthalmus maximus) rearing units. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 27:360-371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hugh, R., and E. Leifson. 1953. The taxonomic significance of fermentative versus oxidative metabolism of carbohydrates by various gram-negative bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 66:24-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Irianto, A., and B. Austin. 2002. Probiotics in aquaculture. J. Fish Dis. 25:633-642. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jöborn, A., J. C. Olsson, A. Westerdahl, P. L. Conway, and S. Kjelleberg. 1997. Colonization in the fish intestinal tract and production of inhibitory substances in intestinal mucus and faecal extracts by Carnobacterium sp. strain K1. J. Fish Dis. 20:383-392. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Larsen, J. L. 2004. Personal communication. The Royal Veterinary and Agricultural University, Copenhagen, Denmark.

- 26.Long, R. A., and F. Azam. 2001. Antagonistic interactions among marine pelagic bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:4975-4983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maeda, M., K. Nogami, M. Kanematsu, and K. Hirayama. 1997. The concept of biological control methods in aquaculture. Hydrobiologia 358:285-290. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marco-Noales, E., E. G. Biosca, C. Rojo, and C. Amaro. 2004. Influence of aquatic microbiota on the survival of the human and eel pathogen Vibrio vulnificus serovar E. Environ. Microbiol. 6:364-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moran, M. A., J. M. González, and R. P. Kiene. 2003. Linking a bacterial taxon to sulfur cycling in the sea: studies of the marine Roseobacter group. Geomicrobiol. J. 20:375-388. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moriarty, D. J. W. 1998. Control of luminous Vibrio species in penaeid aquaculture ponds. Aquaculture 164:351-358. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moriarty, D. J. W. 1999. Disease control in shrimp aquaculture with probiotic bacteria. In C. R. Bell, M. Brylinsky, and P. Johnson-Green (ed.), Microbial biosystems: new frontiers. Proceedings of the 8th International Symposium on Microbial Ecology. [Online.] Atlantic Canada Society for Microbial Ecology, Halifax, Canada. http://ag.arizona.ed/azaqua/tilapia/tilapia_shrimp/moriarty.pdf.

- 32.Munro, P. D., T. H. Birkbeck, and A. Barbour. 1993. Influence of rate of bacterial colonisation of the gut of turbot larvae on larval survival, p. 85-92. In H. Reinertsen, L. A. Dahle, L. Jørgensen, and K. Tvinnereim (ed.), Fish farming technology. Bakema, Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

- 33.Nikoskelainen, S., S. Salminen, G. Bylund, and A. C. Ouwehand. 2001. Characterization of the properties of human- and dairy-derived probiotics for prevention of infectious diseases in fish. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:2430-2435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Olsson, J. C., A. Westerdahl, P. L. Conway, and S. Kjelleberg. 1992. Intestinal colonization potential of turbot (Scophthalmus maximus)- and dab (Limanda limanda)-associated bacteria with inhibitory effects against Vibrio anguillarum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:551-556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pyle, B. H., and G. A. McFeters. 1990. Iodine susceptibility of pseudomonads grown attached to stainless steel surfaces. Biofouling 2:113-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Robertson, P. A. W., C. O'Dowd, C. Burrells, P. Williams, and B. Austin. 2000. Use of Carnobacterium sp. as a probiotic for Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) and rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss, Walbaum). Aquaculture 185:235-243. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sambrook, J., and D. W. Russell. 2001. Molecular cloning. A laboratory manual, 3rd ed., appendix A2.2. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 38.Selje, N., M. Simon, and T. Brinkhoff. 2004. A newly discovered Roseobacter cluster in temperate and polar oceans. Nature 427:445-448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Skov, M. N., K. Pedersen, and J. L. Larsen. 1995. Comparison of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, ribotyping, and plasmid profiling for typing of Vibrio anguillarum serovar O1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61:1540-1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spanggaard, B., I. Huber, J. Nielsen, T. Nielsen, and L. Gram. 2000. Proliferation and location of Vibrio anguillarum during infection of rainbow trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss (Walbaum). J. Fish Dis. 23:423-427. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Spanggaard, B., I. Huber, J. Nielsen, E. B. Sick, C. B. Pipper, T. Martinussen, W. J. Slierendrecht, and L. Gram. 2001. The probiotic potential against vibriosis of the indigenous microflora of rainbow trout. Environ. Microbiol. 3:755-765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Strøm, E., and E. Ringø. 1993. Changes in the bacterial composition of early developing cod, Gadus morhua (L.) larvae following inoculation of Lactobacillus plantarum into the water, p. 226-228. In B. T. Walther and H. J. Fyhn (ed.), Physiological and biochemical aspects of fish development. University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway.

- 43.Thomson, R., H. L. Macpherson, A. Riaza, and T. H. Birkbeck. Unpublished data.

- 44.Westerdahl, A., J. C. Olsson, S. Kjelleberg, and P. L. Conway. 1991. Isolation and characterization of turbot (Scophthalmus maximus)-associated bacteria with inhibitory effects against Vibrio anguillarum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 57:2223-2228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]